Abstract

Stuttering is characterized by disrupted fluency of verbal expression, and occurs mostly in children. Persistent developmental stuttering (PDS) may occur in adults. Reports of the surgical management of PDS are limited. Here we present the case of a 28-year-old man who had had PDS since the age of 7 years, was diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorder at the age of 24 years, and had physical concomitants. He underwent a bilateral anterior capsulotomy 4 years after the diagnosis. Over one year of follow-up, his physical concomitants resolved, and significant improvements in his psychiatric disorders and PDS were observed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of simultaneous improvement in a patient’s PDS and psychiatric disorder after a bilateral anterior capsulotomy.

Introduction

Stuttering is a disorder defined by frequent prolongations, repetitions, or blocks of spoken sounds and/or syllables, as well as anxiety and cognitive avoidance. Coexisting symptoms may include facial grimacing and tremors of the muscles involved in speech.Citation1 Stuttering affects approximately 5% of children and 1% of the adult population.Citation1 Most stuttering undergoes spontaneous recovery.Citation1 Speech and language therapy is the most common treatment for stuttering.Citation2

Persistent developmental stuttering (PDS) is a form of stuttering that occurs in early childhood and does not resolve spontaneously or respond to speech therapy.Citation3 Many PDS patients have an increased risk of psychiatric and behavioral problems.Citation4 Although successful surgical management of patients with refractory psychiatric disorders has been reported,Citation5,Citation6 the evidence for surgical treatment of PDS and associated psychiatric disorders is limited.Citation7

Case report

A 28-year-old male first presented with stuttering at the age of 7 years. No management was carried out at that time because his symptoms were mild. By the age of 20 years, he was being ridiculed and humiliated by his college classmates. He became more introverted and did not want to communicate with others. Since then, his stuttering had worsened. He experienced multiple blocks in expressing words, including sound and syllable repetitions, circumlocutions, and monosyllabic repetitions, that made it difficult to conduct the interview.

In addition to deterioration of his PDS, he developed depression and anxiety and was afraid to communicate with others. He also had physical concomitants of involuntary jerking of his head and upper extremities and muscle spasm of his neck and lower jaw while stuttering. He was diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorder by the psychiatrists at the age of 24 years. He was managed medically with multiple antipsychotics in conjunction with cognitive behavioral therapy. Significant improvement in his psychiatric disorder but not his PDS was achieved at that time.

One year earlier, because of his local culture, he had refused to take any medicine, which led to a relapse of his psychiatric symptoms. Subsequent antipsychotics and cognitive behavioral therapy were of limited help in alleviating his psychiatric symptoms. We carefully addressed his treatment options, which included further medical treatment, deep brain stimulation, or capsulotomy. Both the patient and his family opted for capsulotomy for financial reasons and in the hope of being able to avoid using antipsychotics. The surgery was approved by the ethics committee at our hospital.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging was done to rule out an intracranial tumor, hemorrhage, infarction, and infection. No family history of a speech disorder was reported. The preoperative neuropsychological evaluations were carried out using the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,Citation8 the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale,Citation9 the Mini-Mental State Examination,Citation10 the similarities and block design subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence scale,Citation11 the logical memory and visual reproduction subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale,Citation12 and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-Simplified (WCST-S).Citation13 Both the logical memory and visual reproduction tests were carried out immediately and after a 30-minute delay. The WCST-S included 48 cards, and his performance was assessed by the number of correct answers, number of errors, number of perseverative errors, number of nonperseverative errors, and number of categories completed. Neuropsychological and PDS evaluations were done before surgery and at 6-month follow-up by the same psychiatrist and speech therapist, who were both aware that the patient had undergone neurosurgery.

Surgery

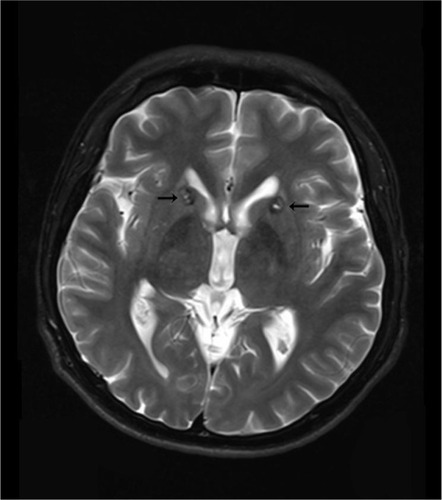

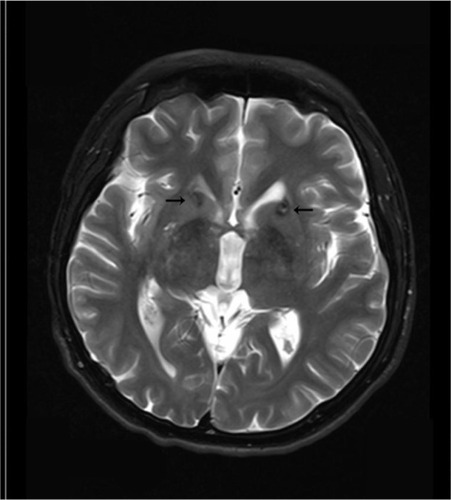

To better identify the magnetic resonance images without fixation of the head frame were obtained the day before surgery. A 3 T Trio Unite magnetic resonance imaging system (Siemens AG, Muenchen, Germany) was used with T1-weighted and T2-weighted spin-echo sequences in the axial and coronal planes. The slice thickness was 2 mm with an interval gap of 0.02 mm. The preplanning procedure was completed using the Surgi-plan workstation (version 2.1; Elekta Instruments AB, Stockholm, Sweden). On the day of surgery, a Leksell model G head frame (Elekta Instruments AB) was positioned on the skull parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line under local anesthesia. A repeat magnetic resonance scan with the same parameters as the preplanning scanning was performed using a 1.5 T Sonata Unite magnetic resonance imaging system (Siemens AG). With the help of the Surgi-plan workstation, the prescanned images were then coregistered with the images using location markers. The coordinates of the target and the angles of electrode penetration were calculated. The lesion targets were located 14 mm anterior and 18 mm lateral to the anterior commissure and 5 mm below the anterior commissure–posterior commissure plane. Under the guidance of the Leksell multifunctional stereotactic operation system (Elekta Instruments AB), the lesion electrode was then inserted into the lesion target according to the calculated coordinates. A test stimulation generated by the Elekta neurostimulator at both high frequency (130 Hz) and low frequency (5 Hz) was then carried out to verify the target of the electrode. Next, multiple lesions were produced using the Elekta neurostimulator at 75°C for 70 seconds each. The length of the lesions on both sides was 14 mm ( and ).

Post-surgical outcome

The patient’s physical concomitants disappeared on the second day after surgery. Slow reaction, lack of concentration, and mild somnolence were observed during the first week, but most of these symptoms disappeared 10 days after surgery.

One month after surgery, the patient reported improvement in his symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PDS, except for some naïve behaviors (sucking and biting his fingers), mild memory loss, and laziness. Three months after surgery, the patient reported being interested in daily life and feeling more confident. Six months after surgery, the patient reported that his psychiatric symptoms were significantly improved. Although the symptoms of his PDS occurred occasionally, these were mild and could be controlled by ego psychology. Complete remission of the naïve behaviors, mild memory loss, and laziness were documented 1 month after surgery. One year after surgery, the patient returned to work, reporting improved mood and better social and work relationships. Although complete remission of his PDS was not achieved, he could communicate with others more fluently.

Stuttering

Six months after surgery, the patient’s symptoms improved from very severe speech impairments on the Stuttering Severity Instrument 3Citation14 and 8/9 for speech naturalnessCitation15 to mild speech impairments on the Stuttering Severity Instrument 3 and 3/9 for speech naturalness. Both the severity of stuttering and naturalness of speech improved significantly 6 months after surgery.

Neuropsychological status

Neuropsychological evaluations () were carried out before surgery, 1 month after surgery, 3 months after surgery, and 6 months after surgery. His scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale decreased markedly 6 months after surgery, which is in accordance with the significant improvement in his psychiatric symptoms at 6-month follow-up. Neuropsychological evaluation tests were used to assess and detect whether there were neurocognitive impairments after surgery.

Table 1 Neuropsychological evaluation tests at 6-month follow-up

Cognitive impairment is common in young adults with major depression and anxiety disorder.Citation16 The raw data from the block design, logical memory, and WCST-S indicate that the patient’s impairments of visuospatial function, verbal memory, concentration, and executive function before surgery were significantly improved 6 months after surgery.Citation16 The raw data for the WCST-S at 1 month after surgery, which were lower than the data before surgery but increased at 6-month follow-up, showed that his executive functioning worsened transiently following surgery and improved thereafter. This may be why the patient had naïve behaviors, mild memory loss, and laziness at the 1 month follow-up that completely disappeared 6 months after surgery.Citation13

Discussion

The tics associated with Tourette’s syndrome are defined as involuntary, sudden, rapid, recurrent, nonrhythmic movements (motor tics) or vocalizations (vocal or phonic tics). The onset of Tourette’s syndrome is before the age of 18 years. Patients with Tourette’s syndrome can voluntarily suppress tics for short periods at the expense of mounting inner tension and a subsequent rebound in tic severity.Citation17 Our patient had involuntary movements when he was 20 years old, which occurred only when he stuttered. He was not able to suppress these movements, as in Tourette’s syndrome. We consider these involuntary movements to be physical concomitants of his PDS.

The ventral prefrontal cortex is associated with depression, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and several psychiatric disorders.Citation18 The ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) projections to the subcortical regions travel primarily in the internal capsule and external capsule. Subcortical fibers pass through the external capsule to the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule.Citation18 Thus, an anterior capsulotomy may affect the vPFC through the projectional fibers from the vPFC and result in significantly improved psychiatric symptoms. The axons from the vPFC reach cortical targets primarily via the uncinate fasciculus, extreme capsule, and superior longitudinal fasciculus.Citation18 The frontal operculum supporting local phrase structure building was connected via the uncinate fasciculus to the anterior superior temporal gyrus which has been shown to be involved in phrase structure building.Citation19 The extreme capsule is involved in the human language system.Citation20 The superior longitudinal fasciculus is situated in the white matter of the parietal and frontal opercula and extends to the ventral premotor and prefrontal regions.Citation21 All these studies show that there are association fibers between the frontal operculum and the vPFC. The left pars opercularis is where the intrinsic functional architecture of speech–language processes are altered in PDS patients.Citation22 Therefore, an anterior capsulotomy may affect the left pars opercularis through the vPFC and the association fibers between the vPFC and the pars opercularis, which are involved in the language system. The corticostriatothalamocortical (CSTC) pathways project from specific territories in the frontal cortex to corresponding targets within the striatum, then via pathways through the basal ganglia to the thalamus and, finally, with recurrent projections back to the original frontal territory where each loop started; this dysfunction and disorder of the chemistry circuit of the CSTC is a popular basis of neuropsychiatric diseases.Citation23 Dorsal/ventral organization of thalamic/brainstem fibers through the internal capsule results in a complex mingling of thalamic and brainstem axons from various vPFC areas.Citation18 Thus, there are association fibers between the vPFC and the CSTC.

Stutterers are likely to exhibit a hypometabolism of the striatum and increased dopamine activity.Citation1,Citation24 Overactivity in the area of the basal ganglia in PDS has been reported in several studies, suggesting that the dopaminergic system plays an important role in the development of stuttering.Citation25,Citation26 Most antipsychotics ( and ) are dopamine receptor antagonists and induce changes in the dopaminergic system and activity of the basal ganglia in the CSTC, and this is followed by improvement in psychiatric symptoms and PDS.Citation1

Table 2 Case reports on the treatment of PDS in adults

Table 3 Controlled studies on the treatment of PDS in adults

Although improvements in PDS were an unexpected outcome in our patient, this report suggests a close relationship between PDS and psychiatric disorders.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MaguireGAYehCYItoBSOverview of the diagnosis and treatment of stutteringJ Exp Clin Med2012429297

- MaguireGFranklinDVatakisNGExploratory randomized clinical study of pagoclone in persistent developmental stuttering: the examining pagoclone for persistent developmental stuttering studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol2010301485620075648

- DiasFMPereiraPMDoyleFCTeixeiraALPsychiatric disorders in a patient with persistent developmental stutteringClin Neuropharmacol201134519920021926485

- IverachLJonesMO’BrianSThe relationship between mental health disorders and treatment outcomes among adults who stutterJ Fluency Disord2009341294319500713

- RuckCKarlssonASteeleJDCapsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: long-term follow-up of 25 patientsArch Gen Psychiatry200865891492118678796

- AndersonRJFryeMAAbulseoudOADeep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, safety and mechanisms of actionNeurosci Behav Rev201236819201933

- BalamuraliGBukhariSCarterJSofatAImprovement of persistent developmental stuttering after surgical excision of a left perisylvianmeningiomaBr J Neurosurg201024448548720726757

- HamiltonMA rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1960231566214399272

- HamiltonMThe assessment of anxiety states by ratingBr J Med Psychol1959321505513638508

- TombaughTNMcIntyreNJThe Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc19924099229351512391

- WechslerDManual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence ScaleNew York, NY, USAPsychological Corporation1955

- WechslerDWechsler Memory ScaleNew York, NY, USAPsychological Corporation1945

- LiBSunJHLiTYangYCNeuropsychological study of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and their parents in China: searching for potential endophenotypesNeurosci Bull201228547548222961476

- RileyGDA stuttering severity instrument for children and adultsJ Speech Hear Disord19723733143225057250

- MartinRRHaroldsonSKTridenKAStuttering and speech naturalnessJ Speech Hear Disord198449153586700202

- CastanedaAETuulio-HenrikssonAMarttunenMSuvisaariJLönnqvistJA review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adultsJ Affect Disord2008106112717707915

- CavannaAESeriSTourette’s syndromeBMJ2013347f496423963548

- LehmanJFGreenbergBDMcIntyreCCRasmussenSAHaberSNRules ventral prefrontal cortical axons use to reach their targets: implications for diffusion tensor imaging tractography and deep brain stimulation for psychiatric illnessJ Neurosci20113128103921040221753016

- FriedericiADPathways to language: fiber tracts in the human brainTrends Cogn Sci200913417518119223226

- RolheiserTStamatakisEATylerLKDynamic processing in the human language system: synergy between the arcuate fascicle and extreme capsuleJ Neurosci20113147169491695722114265

- MakrisNKennedyDNMcInerneySSegmentation of subcomponents within the superior longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo, DT-MRI studyCereb Cortex200515685486915590909

- LuCChenCPengDNeural anomaly and reorganization in speakers who stutter: a short-term intervention studyNeurology201279762563222875083

- MiladMRRauchSLObsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathwaysTrends Cogn Sci2012161435122138231

- WuJCMaguireGRileyGIncreased dopamine activity associated with stutteringNeuroreport1997837677709106763

- GiraudALNeumannKBachoud-LeviACSeverity of dysfluency correlates with basal ganglia activity in persistent developmental stutteringBrain Lang2008104219019917531310

- AlmPAStuttering and the basal ganglia circuits: a critical review of possible relationsJ Commun Disord200437432536915159193

- KumarABalanSFluoxetine for persistent developmental stutteringClin Neuropharmacol2007301585917272973

- Mozos-AnsorenaAPérez-GarcíaMPortela-TrabaBTabernero-LadoAPérez-PérezJStuttering treated with olanzapine: a case reportActas Esp Psiquiatr201240423123322851483

- MaguireGAFranklinDLKirstenJAsenapine for the treatment of stuttering: an analysis of three casesAm J Psychiatry2011168665165221642484

- RanjanSSawhneyVChandraPSPersistent developmental stuttering: treatment with risperidoneAust N Z J Psychiatry200640219316476140

- TavanoABusanPBorelliMPelamattiGRisperidone reduces tic-like motor behaviors and linguistic dysfluencies in severe persistent developmental stutteringJ Clin Psychopharmacol201131113113421192161

- TranNLMaguireGAFranklinDLRileyGDCase report of aripiprazole for persistent developmental stutteringJ Clin Psychopharmacol200828447047218626285

- MaguireGARileyGDFranklinDLGottschalkLARisperidone for the treatment of stutteringJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020447948210917410

- MenziesRGO’BrianSOnslowMPackmanASt ClareTBlockSAn experimental clinical trial of a cognitive-behavior therapy package for chronic stutteringJ Speech Lang Hear Res20085161451146418664696