Abstract

Nonepileptic seizures (NES) apparently look like epileptic seizures, but are not associated with ictal electrical discharges in the brain. NES constitute one of the most important differential diagnoses of epilepsy. They have been recognized as a distinctive clinical phenomenon for centuries, and video/electroencephalogram monitoring has allowed clinicians to make near-certain diagnoses. NES are supposedly unrelated to organic brain lesions, and despite the preponderance of a psychiatric/psychological context, they may have an iatrogenic origin. We report a patient with NES precipitated by levetiracetam therapy; in this case, NES was observed during the disappearance of epileptiform discharges from the routine video/electroencephalogram. We discuss the possible mechanisms underlying NES with regard to alternative psychoses associated with the phenomenon of the forced normalization process.

Introduction

Nonepileptic seizures (NES), also known as pseudoseizures or hysterical fits,Citation1 are included in epileptic psychotic manifestations. NES are paroxysmal, time-limited episodes of abnormal behavior or obtunded consciousness, movements, sensations, and psychic states that may be mistaken for epilepsy, but are not accompanied by electroencephalogram (EEG) changes. In accordance with O’Hanlon et al,Citation2 we prefer the acronym NES to the term pseudoseizures. NES are a common clinical problem for family physicians, internists, psychiatrists, neurologists, and neurosurgeons. This type of behavioral disturbance has a poorly defined epidemiology, reflecting difficulties in establishing its prevalence and incidence. Various estimates suggest that 5%–25%Citation3 of patients being evaluated for epileptic seizures actually have NES, and thus NES are a significant health care problem.Citation4 Although concepts concerning the etiology of NES are still in evolution, psychological explanations currently predominate: NES are considered a learned pattern of behavior due to environmental stressors.Citation5 Improved diagnostic capabilities (especially video EEG) have shown that NES are more common than once believed,Citation6 and are not exclusively associated with temporal lobe epilepsy.Citation7,Citation8 Patients with NES are often misdiagnosed as suffering from intractable epilepsy, and are thus potentially exposed to unnecessary anticonvulsant medications and other iatrogenic consequences.Citation6

Although there is variability in the data, there is a general consensus that psychiatric disorders are more prevalent in patients with epilepsy than in the general population.Citation7 Psychosis encompasses a broad and subtle mental condition. Common features include impaired content and coherence of thought, reduced connection to reality, hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech and behavior, and extremes of affect and motivation. The detection of psychosis can be difficult, as many patients actively hide their aberrant behavior and delusional beliefs, and others are quietly psychotic, showing only quirky mannerisms.Citation9 As in other chronic disorders, the prevalence rates of psychiatric symptoms in epilepsy vary widely among the different studies published in the literature, with higher prevalence among patients with poorly controlled seizures.Citation9–Citation12 Psychoses can occur during seizure freedom and during or after epileptic seizures. Epileptic psychoses include also the phenomenon of the forced normalization process (FN) and de novo psychosis following epilepsy surgery. FN is characterized by a subacute/acute onset of psychosis associated with dramatic reduction of epileptiform activity.

Neurologists and psychiatrists have debated the existence of the phenomenon of forced normalization since its description by Landolt in 1953,Citation13 who introduced the concept with two cases who both developed personality and mood changes in association with normalization of their EEGs. LandoltCitation13 defined FN as “the phenomenon characterized by the fact that, with the occurrence of psychotic states, the EEG becomes more normal or entirely normal, as compared with previous and subsequent EEG findings”. The literature in the nineteenth century reveals a growing interest in this relationship, particularly in France and Germany, and there are clear descriptions of specific psychopathological states and epilepsy.Citation14 At this time, such terms as epileptic equivalents, larval epilepsy, and transformed epilepsy seem to have crept into the literature, and generally indicate an alteration in the seizure status and/or the development of a behavioral disorder.

The emergence of new anticonvulsant drugs in the past decade and the increased reporting of behavioral disturbances with several of these drugs, associated with an improvement in seizure status, however, have brought FN again into the focus of scientific attention and curiosity. Patients taking ethosuximide, vigabatrin, levetiracetam (LEV), and topiramate (TPM) with multiple daily seizures (mostly if focal and originating from the limbic lobe), sleep disturbances, and previous psychiatric disorders seem to be more vulnerable.Citation15 FN has only been rarely reported in children and adolescents.Citation16

We describe for the first time NES as expression of the FN process based on Krishnamoorthy and Trimble criteria ().Citation17,Citation18 The patient was taking TPM and LEV. NES after LEV administration has also been reported in a previous study.Citation19

Table 1 Primary and supportive diagnostic criteria for FN

Case report

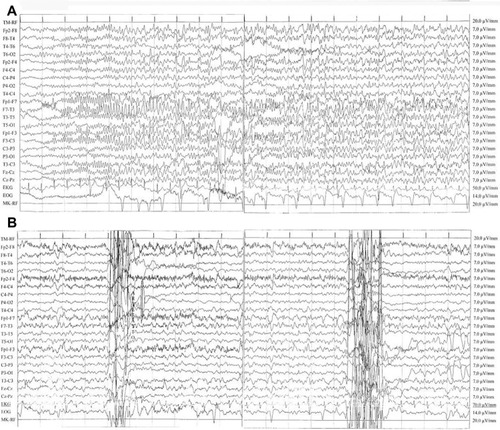

A 53-year-old right-handed woman suffered from focal epilepsy,Citation20 with seizures characterized by abrupt loss of consciousness and tonic and clonic phases. Her clinical history was significant for a family history of febrile seizures, a poor therapeutic compliance associated with recurrences of epileptic seizures, a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, and a recent reactive depression with psychosomatic symptoms and insomnia; the Hamilton rating scale assessed a score of moderate depression. She denied previous pseudoseizures, but her relatives referred to behavioral disturbances in the past (she presented anxiety and irritability often in seizure-free periods). Magnetic resonance imaging findings were normal. Interictal EEG abnormalities in left frontocentrotemporal channels were characterized by repetitive nonperiodic sharp waves at 100 mV with reversal phase on F7 and sporadic anterior synchronous and asynchronous theta activity (6–7 Hz, 50–60 mV). Due to thrombocytopenia, previous treatment with valproic acid was progressively reduced with recurrences of seizures. Considering the obesity of the patient, TPM was titrated up to a total dose of 300 mg/day. Good seizure control was obtained, but 3 months later the patient was admitted to our neurology clinic, due to abnormal behavior and confusion; she presented with spatial/temporal disorientation, she aimlessly moved her hands, and she was slowly turning her head right and left. She presented with postictal aphasia. Video EEG monitoring revealed incoming seizures with a left frontotemporal focus (; Supplementary video). She received 10 mg of diazepam intravenously. The background EEG improved, showing generalized theta activities at a frequency of 6–7 Hz. Subsequently, her therapy was changed: LEV was added and titrated rapidly until 1,000 mg twice daily. After 10 days, new episodes occurred: the patient appeared confused, she did not want to get out of bed, and when she answered our questions appropriately, she lamented about abdominal pain and asthenia. In addition, she had brief and repetitive tonic jerks of the trunk unaccompanied by loss of consciousness. During these episodes, which lasted about 50 seconds, her eyes were closed. Then she appeared drowsy for 10–15 minutes and could not recall these events. Immediately, EEG monitoring () was performed, and it revealed no ictal abnormalities during these episodes, but only sporadic interictal sharp waves noted at baseline, supporting a diagnosis of NES. We observed a reduction of the epileptic activity in more than 50% of the waking EEG recording. The reduction of TPM to 100 mg twice daily, the withdrawal of LEV and the introduction of lacosamide titrated to a dose of 300 mg/day led to immediate resolution of NES. During follow-up examinations, neither seizures nor NES were reported anymore by patients and relatives.

Figure 1 (A) Seizure with a left frontotemporal focus. Ictal electroencephalography (EEG) showed rhythmic and reluctant fast (12–13 Hz) activity primarily involving the left frontotemporal area consisting of polyspikes of about 100 mV amplitude with reversal phase in the F7 lead, then epileptic discharge involved all channels and showed a reduction in frequency (6 Hz). The patient was unconscious. Discharges consisting of high-amplitude sharp waves (90–100 μV) and slow waves (prominent on the frontotemporal areas) (high 30 Hz, low 0.1 second; rate 15 mm/second). (B) EEG during pseudoseizures. Normal background activity with interictal abnormalities in left frontocentrotemporal channels: sporadic and nonperiodic sharp waves at 100 mV with reversal phase on F7 and sporadic anterior synchronous and asynchronous theta activity (6–7 Hz, 50–60 mV). Muscular artifacts on right frontal derivations and two abrupt movement artifacts were concomitant with fictitious spasms of the patient. No epileptic seizures were recorded. This recording showed a significant reduction of interictal activity in comparison with her previous EEGs.

Discussion

Nonepileptic seizures

NES are classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition) as a somatoform disorder.Citation21 The condition is poorly understood, and is under-recognized by clinicians. The estimated incidence in an epilepsy outpatient clinic is 5%–25%.Citation3 The correct diagnosis of NES, further complicated by the frequent coexistence of epilepsy, can be difficult if simply based on clinical criteria; a video EEG is always necessary. Several studies have described various semiological features of NES.Citation22–Citation24 Physical symptoms are suspected to result from psychosocial stress, and are only rarely intentional, as in malingering. NES are often suspected in patients with a history of somatization, abuse, or psychiatric comorbidity,Citation25 or when the following clinical signs are identified:Citation26 long duration, fluctuating course, asynchronous movements, pelvic thrusting, side-to-side head or body movement, ictal crying, memory recall, closed eyes, the uncommon ictal stuttering, and the “teddy-bear sign”. Our knowledge of the clinical picture and context of NES has made only modest progress since GowersCitation27 summarized his understanding of “hysteroid” seizures in 1885, presenting criteria for distinguishing organic from inorganic seizures; at the end of the nineteenth century, Charcot was the first to describe “hysteroepilepsy” as a clinical disorder.Citation28 The lack of consensus to define and categorize the illness underlies the complexity encountered in establishing effective treatment methodologies, and raises questions regarding the current diagnostic criteria. To address some of these issues, the broad expression “functional neurological disorder” is used for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition).Citation29 The etiology of NES is not entirely understood. Our case shows that it might have an iatrogenic origin, and could be resolved after drug discontinuation. LEV is an anticonvulsant with a favorable safety profile, but behavioral side effects are frequently reported, and were found to be independent of dose or seizure frequency.Citation30 Possible mechanisms underlying behavioral disorders are idiosyncratic dose-unrelated drug effects, significantly increased by antiepileptic drugs, and alternative psychoses (or behavioral disturbances) associated with the phenomenon of FN. Dose-related toxicity and withdrawal syndromes have less importance. The existence of NES as a reversible drug-induced side effect has been identified. Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and vigabatrin with significant γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic properties and LEV with atypical mechanism of action produce behavioral side effects; NES are a behavioral problem. A case of NES appearing as an LEV side effect has previously been reported.Citation19

Forced normalization

There was a mutual antagonism between seizures and psychiatric problems: as the seizures improved, the psychiatric problem emerged. Neidermeyer et alCitation1 suggested that preexisting “cerebral dysfunction” predisposes certain individuals to exhibit NES, and diffuse electroencephalographic slow-wave activity arising from anticonvulsant toxicity facilitates their expression. Since FN often occurs after an effective antiepileptic drug is added, the psychosis could be a side effect of medication, with EEG improvement an epiphenomenon. The concept of FN, first described by Landolt,Citation13 refers to conditions where the disappearance of epileptiform discharges from the routine EEG is accompanied by some kind of behavioral disorder. The pathogenesis of this condition is debated. The most interesting hypotheses have been discussed by Wolf,Citation31 who assumed that during “paradoxical normalization”, a term that he preferred, the epilepsy is still active subcortically: the spread of discharge along unusual pathways is supposed to induce some of the acute psychotic symptoms. More recently, BobCitation32 analyzed the FN concept, hypothesizing that dissociative and somatoform symptoms mainly occur as a consequence of traumatic events. Even though FN has been recognized for a long time, the majority of published papers are case reports, probably as a result of the lack of validated diagnostic criteria. Only Krishnamoorthy and TrimbleCitation17 have proposed primary and supportive diagnostic criteria (), which have been revisited more recently.Citation18 Ideally, such criteria should be tested, suitably modified if required, and adopted by scientific organizations that promote epilepsy research. Uniform diagnostic criteria such as these are the first step in systematic research. Our patient fulfills all the primary and supportive criteria; therefore, she was more susceptible to the occurrence of FN, regardless of other provoking factors. Although a past history of psychosomatic symptoms and moderate depression are significant risk factors for NES, we showed the occurrence of behavioral abnormalities when a reduction of epileptic activity was observed in more than 50% of the waking EEG recording (compared to a similar recording performed during a normal state of behavior over 60 minutes) in a patient with an established diagnosis of epilepsy, with subacute onset of behavioral disturbance and a report of complete absence of seizures for at least 1 week (, Primary criteria). Furthermore the drug regimen was recently changed and parents referred to behavioral disturbances in the past (, Supportive criteria). Therefore, for the first time we have described and documented NES during a forced normalization process, pointing out that NES can be one of the multiple expressions of psychosis in FN. We obtained a resolution of the NES after LEV discontinuation, TPM reduction, and lacosamide introduction. For ethical reasons, we could not remove drug therapy to prove the disappearance of NES concomitant with the reappearance of the epileptic activity.

Conclusion

We hypothesized that in our case, FN was induced by LEV fast titration. Probably, lacosamide therapy controlled seizures without inducing FN, due to its different mechanism of action, although the impact of drug type and its mechanism of action is unclear.Citation33 It is known that alterations in the balance of glutaminergic, dopaminergic, and GABA activity may cause seizures and behavioral disorder and can also play a role in the development of FN.Citation17 The emergence of new anticonvulsant drugs in the past decade and the increased reporting of behavioral disturbances with several of these drugs, associated with an improvement in seizure status, underlines the complexity of interaction between several potential pathogenic factors as the possible cause of FN. It is of interest that LandoltCitation13 himself commented on the increase in the number of cases of FN with the introduction of succinimide drugs. Other researchers also observed this with barbiturates and hydantoins.Citation33 No data have reported behavioral side effects or FN cases with lacosamide, whereas both LEV and TPM might have induced NES: the patient had already been taking a stable dose of TPM for 3 months; therefore, it is likely that the psychotic episode could be ascribed to LEV introduction. In fact, during add-on therapy, we obtained EEG normalization. An interesting trial with LEV and TPMCitation15 showed that some patients are prone to develop psychiatric drug-induced adverse events, regardless of pharmacological properties, and that an early limbic injury predisposes people to this type of psychiatric vulnerability. In our opinion, sudden seizure control obtained with fast titration and drug mechanism of action are in some selective cases the relevant factors for the development of psychosis in the FN process, while the association with a specific epilepsy syndrome may represent a bias connected to the probability of achieving complete seizure suppression: patients with symptomatic or multifocal epilepsy are less likely to be seizure-free than patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy, which is usually associated with a better prognosis. Systematic research that identifies patients who meet Trimble’s criteria in hospital-, institutional-, and community-based population groups, grafted onto modern techniques in molecular genetics and functional imaging,Citation34 may well be the way forward in understanding this fascinating condition. Effective research in this area requires a combined attempt to establish international protocols and databases, while respecting patient privacy and rights.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NeidermeyerEBlumerDHolscherEWalkerBAClassical hysterical seizures facilitated by anticonvulsant toxicityPsychiatr Clin (Basel)1970371845424766

- O’HanlonSListonRDelantyNPsychogenic nonepileptic seizures: time to abandon the term pseudoseizuresArch Neurol2012691349135023044592

- SzaflarskiJPFickerDMCahillWTPriviteraMDFour-year incidence of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in adults in Hamilton County, OHNeurology2000551561156311094115

- BettsTABodenSPseudoseizures (non-epileptic attack disorder)TrimbleMWomen and EpilepsyNew YorkWiley1991243258

- RamaniSVQuesneyLFOlsonDGumnitRJDiagnosis of hysterical seizures in epileptic patientsAm J Psychiatry19801377057097377391

- ReuberMPsychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Answers and questionsEpilepsy Behav20081262263518164250

- KogeorgosJFonagyPScottDFPsychiatric symptom patterns of chronic epileptics attending a neurological clinic: a controlled investigationBr J Psychiatry19821402362436807385

- KannerAMPsychosis of epilepsy: a neurologist’s perspectiveEpilepsy Behav2000121922712609438

- AdamsSJO’BrienTJLloydJKilpatrickCJSalzbergMRVelakoulisDNeuropsychiatric morbidity in focal epilepsyBr J Psychiatry200819246446918515901

- CockerellOCMoriartyJTrimbleMSanderJWShorvonSDAcute psychological disorders in patients with epilepsy: a nation-wide studyEpilepsy Res1996251191318884170

- SperliFRentschDDesplandPAPsychiatric comorbidity in patients evaluated for chronic epilepsy: a differential role of the right hemisphere?Eur Neurol20096135035719365127

- TortaRKellerRBehavioral, psychotic, and anxiety disorders in epilepsy: etiology, clinical features, and therapeutic implicationsEpilepsia199940Suppl 10S2S2010609602

- LandoltHSerial EEG investigations during psychotic episodes in epileptic patients and during schizophrenic attacksLorentzDe Haas AMLectures on EpilepsyAmsterdamElsevier195891133

- SchmitzBForced normalization: history of a conceptTrimbleMRSchmitzBForced Normalization and Alternative Psychosis of EpilepsyPetersfield, UKWrightson Biomedical1998724

- MulaMTrimbleMRSanderJWAre psychiatric adverse events of antiepileptic drugs a unique entity? A study of topiramate and levetiracetamEpilepsia2007482322232617711462

- AmirNGross-TsurVParadoxical normalization in childhood epilepsyEpilepsia199435106010647925152

- KrishnamoorthyESTrimbleMRForced normalization: clinical and therapeutic relevanceEpilepsia199940105764

- KrishnamoorthyESTrimbleMRSanderJWKannercAMControversies in epilepsy and behavior: forced normalization at the interface between epilepsy and psychiatryEpilepsy Behav2002330330812609326

- IgnatencoAArzySGhikaJNonepileptic seizures under levetiracetam therapyEpilepsy Behav20101952652720934390

- BergATBerkovicSFBrodieMJRevised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009Epilepsia20105167668520196795

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disordersfourth editionAmerican Psychiatric PressWashington, DC, USA1994

- ChungSSGerberPKirlinKAIctal eye closure is a reliable indicator of psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology2006661730173116769949

- DeToledoJCRamsayREPatterns of involvement of facial muscles during epileptic and nonepileptic events: review of 654 eventsNeurology1996476216258797454

- VosslerDGHaltinerAMScheppSKIctal stuttering: a sign suggestive of psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology20046351651915304584

- AnzellottiFFranciottiRBonanniLPersistent genital arousal disorder associated with functional hyperconnectivity of an epileptic focusNeuroscience2010167889620144694

- AvbersekASisodiyaSDoes the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20108171972520581136

- GowersWREpilepsy and Other Chronic DiseasesNew YorkWilliam Wood1885

- HavensLLCharcot and hysteriaJ Nerv Ment Dis1965141505516

- StoneJLaFranceWCJrBrownRSpiegelDLevensonJLSharpeMConversion disorder: current problems and potential solutions for DSM-5J Psychosom Res20117136937622118377

- HelmstaedterCFritzNEKockelmannEKosanetzkyNElgerCEPositive and negative psychotropic effects of levetiracetamEpilepsy Behav20081353554118583196

- WolfPAcute behavioral symptomatology at disappearance of epileptiform EEG abnormality. Paradoxical or “forced” normalizationAdv Neurol1991551271422003402

- BobPDissociation, forced normalization and dynamic multi-stability of the brainNeuro Endocrinol Lett20072823124617627254

- TrimbleMRNew antiepileptic drugs and psychopathologyNeuropsychobiology1998381491519778603

- van der KruijsSJBoddeNMVaessenMJFunctional connectivity of dissociation in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizuresJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20128323924722056967