Abstract

Background

Adolescents’ sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being are related. However, few studies have examined the relationship between sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being longitudinally across adolescence – a time of profound biological and psychosocial change. The aim of this longitudinal study was to investigate whether shorter sleep duration in adolescents is predictive of lower subjective psychological well-being 6 months and 12 months later or whether lower subjective psychological well-being is predictive of shorter sleep duration.

Methods

Adolescents (age range, 10.02–15.99 years; mean age, 13.05±1.49 years; 51.8%, female) from German-speaking Switzerland (n=886) and Norway (n=715) reported their sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being on school days using self-rating questionnaires at baseline (T1), 6 months (T2), and 12 months from baseline (T3).

Results

Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses revealed that sleep duration decreased with age. Longer sleep duration was concurrently associated with better subjective psychological well-being. Crossed-lagged autoregressive longitudinal panel analysis showed that sleep duration prospectively predicted subjective psychological well-being while there was no evidence for the reverse relationship.

Conclusion

Sleep duration is predictive of subjective psychological well-being. The findings offer further support for the importance of healthy sleep patterns during adolescence.

Introduction

Complaints about poor sleep and daytime sleepiness are common among adolescents,Citation1,Citation2 and acuteCitation3 and chronicCitation4 sleep disturbances have been related to poor psychological functioning, such as impaired cognitive performance,Citation5,Citation6 depression,Citation7–Citation12 and poor physical health.Citation13–Citation16 Short sleep duration, insomnia, as well as interrupted sleep due to sleep apnea, nocturnal enuresis, and periodic limb movement in children and adolescents adversely affects learning, academic performance,Citation17–Citation23 emotional processing,Citation24–Citation26 and – relatedly – psychological functioning.Citation27–Citation30 In a cross-sectional survey with a large population of college students (n=1,125; 17–24 years old), over 60% of respondents were categorized as poor-quality sleepers with shorter sleep duration.Citation19 Poor sleep quality and sleepiness were independently associated with poor school achievement in children and adolescents.Citation20 Remarkably, over 25% of adolescents report sleep disturbances.Citation7,Citation31–Citation34 Cross-sectionalCitation19,Citation35 and longitudinal studies, eg,Citation36,Citation37 have shown that acute and chronic sleep disturbances persist over time, which may compromise adolescents’ mental and physical health in the long run.

Although older adolescents of 15–16 years still require approximately 9 hours of sleep on average per night as do younger adolescents of around 10–11 years,Citation38–Citation40 a wealth of studies shows that average sleep duration decreases significantly across adolescence.Citation22,Citation41–Citation44 Several factors may be responsible for this decrease, including: physical maturation; psychological factors; social factors, such as decreasing supervision by parents and increasing importance of peer relations; and issues related to education and training, involving pressure related to academic achievement, homework, vocational issues, and extracurricular activities.Citation27,Citation28,Citation38,Citation39,Citation45

Taken together, the pattern of published evidence suggests that sufficient sleep during adolescence is related to adolescents’ psychological well-being. Although there are numerous studies of the relationship between sleep and poor mental health, longitudinal studies focusing on the relationship between sleep duration and positive aspects of functioning, such as psychological well-being, are scarce.Citation46 An exception is a 3-year longitudinal study of 2,259 students aged 11–14 years that showed that depressive symptoms and low self-esteem were predicted by short sleep.Citation47 Positive psychological well-being involves both cognitive and affective aspects.Citation48 Cognitive aspects include evaluations of whether one’s life is on the right track and whether one has a positive attitude toward one’s future. Affective aspects include whether one experiences positive emotions and joy in life as well as an absence of negative affect and symptoms of mental distress.Citation48

The present study extends upon previous research in two respects. First, we studied interrelations between sleep schedules and subjective psychological well-being (SPW) across three time points of measurement testing for both directions of prediction. The measurement points were each separated by 6 months (data were collected in May, November, and again in May). Second, we tested whether associations between sleep duration and SPW are different between age groups. We therefore divided the sample into three age categories: 10–11 year olds; 12–13 year olds; and 14–15 year olds. Sleep duration and SPW were assessed in two large samples of adolescents from Switzerland and Norway. Although both countries are examples of Western cultures, they, for instance, differ markedly with regard to day length in May and November, which may be associated with sleep patterns and SPW.Citation32

Methods

Participants

In total, 2,703 adolescents provided data on at least one measurement time point. A total of 1,601 adolescents (age range at T1, 10.02–15.99 years; mean age, 13.05–1.49 years; 51.8% females) from two different European countries (Switzerland, n=886; Norway, n=715), and from a socioeconomically diverse sample provided complete data across all three measurement waves (T1, n=2,330; T2, n=2,094; T3, n=2,061. As data were assessed during school lessons with school classes, it is possible that, for instance, some participants provided no data at T1 but at a later assessment time). Comparing adolescents with complete data with the ones with incomplete data revealed that participants with complete data were younger (F[1; 2,520]=29.1; P<0.001), more often female (χ2[1]=10.23; P=0.001), had higher levels of SPW at T1 (F[1; 2,363]=23.55; P<0.001), and at T2 (F[1; 2,139]=17.80; P<0.001), as well as longer sleep duration at T1 (F[1; 2,340]=116.04; P<0.001). The two nations did not differ with regard to the probability of having complete data (χ2[1]=0.22; P=0.88). Furthermore, the two national groups differed with respect to age (F[1; 2520]=37.65; P<0.001); the Swiss sample mean age was 13.34±1.54 years; the Norwegian sample mean age was 12.97±1.50 years). Sex distribution was not significant (χ2[1]=0.16; P=0.69). The grades sampled were from fourth to ninth; these school years are compulsory in both countries. Socioeconomic status was: 31%, upper class; 37%, middle class; and 32%, working class. The majority of adolescents lived with both parents (n=2,132; 80%), 18% (n=480) with their mothers only, and just 2% (n=53) with their fathers only.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by advertisements in the local schools in the canton of Bern, located in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and in Bergen (Norway). The first wave of the investigation took place in early summer (May, T1), followed by further waves after 6 months in early winter (November, T2), and again 6 months later in early summer (May, T3). Each assessment took place in the classroom during a school lesson. All participants and their parents gave informed consent regarding study participation. The study followed the ethical principles required by the home institution of the study (the University of Bern, Switzerland) and laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Nationales Forschungsprogramm 33 [NFP-33]; project number, 4033-35779).

Materials

Self-assessment of SPW; Bern well-being questionnaire for adolescents

The present study used five items from the Bern well-being questionnaire for adolescents (BFW/J)-subscale. One item was: “Positive attitude towards life”, such as “My future looks good”, and “I enjoy life more than most of the other people”. Four items from the BFW/J-subscale included: “Joy in life”, such as “Did it occur in the past few weeks that you were pleased because you had achieved something?” or “Did it occur in the past few weeks that you were pleased because other people liked you?” Answers were given on four-point rating scales with 1= “not at all” and 4= “completely”. To increase reliability, the nine items were combined to build a score of subjective psychological well-being. Cronbach’s alpha of this score was 0.77 at T1, 0.81 at T2, and 0.82 at T3, which represents good internal consistency.

Sleep duration on weekdays

Sleep duration on weekdays was assessed with two items asking for time in bed before school days and time of getting up on school days. The participants had to fill in the respective clock times. Sleep duration was calculated by the difference between bed and getting up time.

Statistical analysis

To assess relationships between sleep duration and SPW in different age groups, we divided participants into three age groups representing very early adolescence: (ages 10–11 years; mean age, 11.20±0.50 years); late early adolescence (ages 12–13 years; mean age, 12.96±0.56 years); and early middle adolescence (ages 14–15 years; mean age, 14.94±0.54 years).

To compare differences in SPW and sleep duration between countries, age groups, and across the three waves, two analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for repeated measures were computed with the factors country (Switzerland versus Norway), age group (“10 to 11 year olds” versus “12 to 13 year olds” versus “14 to 15 year olds”), and assessment time (T1, baseline; T2, 6 months from T1; and T3, 12 months from T1). Additionally, Pearson’s correlations between sleep duration and SPW were computed separately for the three age groups and the three assessment times. To test longitudinal relations between sleep duration and SPW controlling for the initial levels of these constructs, a crossed-lagged autoregressive longitudinal panel model was employed. This model specifies autoregressive paths (each construct is regressed on its level at the preceding measurement wave), crossed-lagged paths (each construct is regressed on the other construct’s level at the preceding measurement wave), as well as correlations between the two constructs (or their residuals) on the concurrent measurement wave. This model was estimated separately for the three age groups applying multi-group comparison and the χ2 difference test. For paths that were not significantly different between the three age groups as indicated by the χ2 difference test, the paths were set equal across groups.

An alpha of P<0.05 was accepted as a nominal level of significance. All statistical computations were performed with IBM SPSS® (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and AMOS® 19 for Windows (Amos Development Corporation, Spring House, PA, USA). Missing values were not imputed for analyses conducted with SPSS® (ANOVA for repeated measures, correlations), while analyses conducted with the AMOS® applied estimation of missing values by the full information maximum likelihood method.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the course of sleep duration and SPW across adolescence

There were no significant differences between males and females in SPW (F[df=1]=3.65; P=0.06) or sleep duration (F[df=1]=0.66; P=0.42). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed that sleep duration decreased with age in cross-sectional analysis (ie, analyses comparing the age groups; [F{2; 1,584}=532.23; P<0.001]) and longitudinal analysis (analysis of the trend across the measurement points; [F{2; 1,583}=276.07; P<0.0010]). Sleep duration was shorter in Norway than in Switzerland (F[1; 1,584]=39.94; P<0.001). Age-group X measurement time, country X measurement time, country X age group interactions, and the three-way interaction country X age-group X measurement time were not significant (P>0.10). provides descriptive statistics for sleep duration by countries (Switzerland and Norway), age groups (“10–11 year olds”, “12–13 year olds”, and “14–15 year olds”), and across the three measurement points (T1, T2, and T3). The decline in sleep duration across adolescence is reflected by a decline from 10.00 hours and 9.82 hours among the 10–11 year olds at T1 in Switzerland and Norway, respectively, while the 14–15 year olds slept 8.36 hours and 8.01 hours at T3 in Switzerland and Norway. Inspection of effect sizes of the decline in sleep duration in both countries and all age groups indicated a considerably stronger decrease (ie, double the size or more) in the period from November–May than in the period from May–November (with the exception of the 12–13 year olds in Switzerland).

Table 1 Description of sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being, separated by: CH and N; age groups (I, 10–11 year olds; II, 12–13 year olds; III, 14–15 year olds); and the three measurement time points (T1, T2, and T3)

SPW also decreased with age in cross-sectional (F[2; 1,652]=18.87; P<0.001) and longitudinal analyses (F[2; 1,652]=39.44; P<0.001). SPW was lower in Norway than in Switzerland (F[1; 1,652]=10.93; P<0.001). Moreover, the age-group X measurement time interaction was significant (F[2; 1,652]=3.90; P=0.02; indicating a stronger decline among the 12–13 year olds than in the younger and older age groups), as was the country X measurement time interaction (F[2; 1,651]=8.47; P<0.001; indicating a stronger decline among Norwegian adolescents) while the country X age-group interaction and the three-way interaction were not significant (P>0.10).

Analysis of relationship between sleep duration and SPW

gives the zero-order correlations between sleep duration and SPW in the three age groups. Concurrent correlations between sleep duration and SPW were significantly positive indicating higher levels of SPW among adolescents with longer sleep duration with the exception of concurrent correlations among the 10–11 year olds at T1 and among the 14–15 year olds at T3.

Table 2 Correlations between sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being, separated by the three age groups (I, 10–11 year olds; II, 12–13 year olds; III, 14–15 year olds) and three measurement time points (T1, T2, and T3)

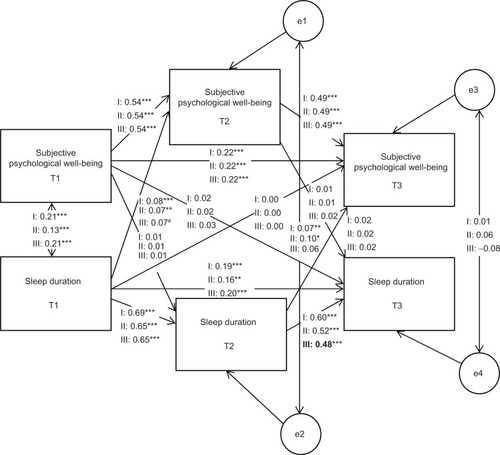

The longitudinal path analysis is displayed in . The paths could be set equal across the three age groups (indicating similarity of the path coefficients in the three age groups) with the exception of the path from sleep duration at T2 on sleep duration at T3, which could only be set equal between the younger two age groups (fit indices for the model allowing this path to vary between the oldest age group and the two younger groups: χ2[23]=28.01; P=0.22, root mean square error of approximation =0.007; fit indices for comparison with the model which additionally sets this path equal across all age groups: χ2[1[=23.35; P<0.001). Generally, the stabilities of sleep duration and SPW from T1 to T2 to T3 were high to very high. Among the crossed lagged paths (the paths between the constructs of sleep duration and SPW across time points), only the path from sleep duration at T1 to SPW at T2 was significant indicating a positive relation between sleep duration at T1 and SPW at T2. This path was of equal strength in the three age groups; however, it represents a quite small effect size.

Figure 1 Longitudinal path model.

Abbreviations: RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; I, 10–11 year olds; II, 12–13 year olds; III, 14–15 year olds; e, error term.

Discussion

Regarding the relationship between sleep duration and SPW, our findings echo evidence from numerous studies that have confirmed an association between adolescents’ sleep duration and subjective psychological well-being.Citation19,Citation35,Citation49–Citation52 Our findings indicate that sleep duration is a longitudinal predictor of SPW. The findings show that affect regulation is compromised by short sleep.Citation24 However, the size of the effect was weak when SPW at baseline was controlled. Moreover, the effect was not consistent across all measurement time points.

By contrast, our findings do not indicate that SPW is a longitudinal predictor of sleep duration. The pattern of results extends upon previous findings in showing that the relationship between sleep duration and SPW across one year is very similar in the three age groups of very early adolescents (10–11 year olds), late early adolescents (12–13 year olds), and early middle adolescents (14–15 year olds).

Regarding changes in sleep duration and SPW across adolescence our findings are consistent with the existing literature by showing that adolescents’ sleep duration decreases with age.Citation43,Citation53 Interestingly, the reduction in sleep duration was smaller between May (a month with already relatively long day length in the northern hemisphere) and November (a month with relatively short day length in the northern hemisphere) than between November and the following May. This difference might reflect a stronger need for sleep in November than in May possibly due to shorter day length. Sleep duration is associated with seasonal changes in day length;Citation54–Citation59 however, we did not find stronger seasonality of sleep duration in Norway than in Switzerland as one might have expected due to the more dramatic seasonal differences in day length in northern countries. While subjective psychological well-being decreased more from May–November than from November–May, this pattern was less pronounced and also inconsistent across subgroups.

Taken together, our findings add to the knowledge that the adolescents’ sleep duration plays an important role for their subjective psychological well-being and may inform school counselors on the importance of adequate sleep duration for the adolescents’ well-being. We note that, while the 10–13 year old adolescents on average still had the recommended sleep duration of 9 hours on weekday nights,Citation40,Citation60 sleep duration was on average shorter for the 14–15 year olds although they still require the same amount of sleep as their younger peers.Citation40 We believe that both adolescents’ and parents’ education in sleep hygiene should be promoted, especially for older adolescents, because of their rapid changes in physiology and behavior,Citation61 including physical maturation, psychological factors, social factors (eg, parental monitoring decreases from younger adolescence to young adulthood, involvement in peer groups increase with a consequent increase in leisure activities), issues related to vocational development, and extracurricular issues. There is also evidence that favourable parental style as well as parental monitoring of adolescents’ bedtimes and stricter household rules with regard to screen time were related to longer sleep and/or better sleep quality,Citation62,Citation63 which may in turn play a role for adolescent’s psychological well-being.Citation24,Citation63–Citation65

Limitations

The strength of this study is the large sample size that allowed to study three different age groups separately, and its longitudinal design. There are also limitations that preclude overgeneralization of the findings. First, objective measurements (eg, actigraphy) would add to the study, allowing comparisons with subjective measurements. Second, we did not include subjective sleep quality to our analyses. Sleep duration is not necessarily associated with subjective sleep quality, and sleep quality and psychological functioning are associated.Citation66 In a related vein, we did not assess other possibly important sleep variables such as sleep debt or circadian preference that would have allowed a more comprehensive picture of adolescents’ sleep habits and circadian rhythms. Third, SPW could have been defined and measured differently. More specifically, future research might include additional dimensions of SPW, such as optimism,Citation67 satisfaction with life,Citation68 and mental toughness.Citation69 Fourth, as no measure of depressive disorder was assessed, it was not possible to test whether the associations also hold if participants with clinically relevant depression were excluded. Finally, applying an intervention design to improve sleep would allow to investigate the causal relationship between sleep duration and psychological functioning.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (NFP-33: Nationales Forschungsprogramm 33; project number: 4033-35779). We thank August Flammer, Françoise Alsaker, Walter Herzog, and Wilhelm Felder who acted as principal investigators of the study, and the NFP33 Study Team for data collection and data entry. The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (principal investigators: August Flammer, Alexander Grob, Françoise Alsaker, Walter Herzog, Wilhelm Felder). We also thank Nick Emler (University of Surrey, UK) for proofreading the manuscript. Finally, we thank the adolescents in Norway and Switzerland as well as their parents for participating in this study and contributing to its success.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HeathACEavesLJKirkKMMartinNGEffects of lifestyle, personality, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and genetic predisposition on subjective sleep disturbance and sleep patternTwin Res19981417618810100809

- SateiaMJDoghramjiKHauriPJMorinCMEvaluation of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine reviewSleep200023224330810737342

- KaneitaYOhidaTUchiyamaMThe relationship between depression and sleep disturbances: a Japanese nationwide general population surveyJ Clin Psychiatry200667219620316566613

- RobertsRERobertsCRDuongHTChronic insomnia and its negative consequences for health and functioning of adolescents: a 12-month prospective studyJ Adolesc Health200842329430218295138

- MeijerAMHabekothéHTVan Den WittenboerGLTime in bed, quality of sleep and school functioning of childrenJ Sleep Res20009214515310849241

- SadehAGruberRRavivASleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age childrenChild Dev200273240541711949899

- AronenETPaavonenEJFjällbergMSoininenMTörrönenJSleep and psychiatric symptoms in school-age childrenJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039450250810761353

- Cohen-ZionMAncoli-IsraelSSleep in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review of naturalistic and stimulant intervention studiesSleep Med Rev20048537940215336238

- El-SheikhMBuckhaltJAMark CummingsEKellerPSleep disruptions and emotional insecurity are pathways of risk for childrenJ Child Psychol Psychiatry2007481889617244274

- GregoryAMO’ConnorTGSleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problemsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241896497112162632

- GregoryAMEleyTCO’ConnorTGPlominREtiologies of associations between childhood sleep and behavioral problems in a large twin sampleJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443674475115167091

- IvanenkoACrabtreeVMObrienLMGozalDSleep complaints and psychiatric symptoms in children evaluated at a pediatric mental health clinicJ Clin Sleep Med200621424817557436

- GangwischJEMalaspinaDBoden-AlbalaBHeymsfieldSBInadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: analyses of the NHANES ISleep200528101289129616295214

- HaslerGBuysseDJKlaghoferRThe association between short sleep duration and obesity in young adults: a 13-year prospective studySleep200427466166615283000

- PatelSRHuFBShort sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic reviewObesity (Silver Spring)200816364365318239586

- VioqueJTorresAQuilesJTime spent watching television, sleep duration and obesity in adults living in Valencia, SpainInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200024121683168811126224

- EspositoMAntinolfiLGallaiBExecutive dysfunction in children affected by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: an observational studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat201391087109423976855

- CarotenutoMEspositoMParisiLDepressive symptoms and childhood sleep apnea syndromeNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2012836937322977304

- LundHGReiderBDWhitingABPrichardJRSleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college studentsJ Adolesc Health201046212413220113918

- DewaldJFMeijerAMOortFJKerkhofGABögelsSMThe influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic reviewSleep Med Rev201014317918920093054

- CurcioGFerraraMDe GennaroLSleep loss, learning capacity and academic performanceSleep Med Rev200610532333716564189

- Perkinson-GloorNLemolaSGrobASleep duration, positive attitude toward life, and academic achievement: the role of daytime tiredness, behavioral persistence, and school start timesJ Adolesc201336231131823317775

- SchabusMHödlmoserKGruberGSleep spindle-related activity in the human EEG and its relation to general cognitive and learning abilitiesEur J Neurosci20062371738174616623830

- TalbotLSMcGlincheyELKaplanKADahlREHarveyAGSleep deprivation in adolescents and adults: changes in affectEmotion201010683184121058849

- WalkerMPvan der HelmEOvernight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processingPsychol Bull2009135573174819702380

- DahlRELewinDSPathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behaviorJ Adolesc Health2002316 Suppl17518412470913

- BrandSKirovRSleep and its importance in adolescence and in common adolescent somatic and psychiatric conditionsInt J Gen Med2011442544221731894

- ColrainIMBakerFCChanges in sleep as a function of adolescent developmentNeuropsychol Rev201121152121225346

- JanJEReiterRJBaxMCRibaryUFreemanRDWasdellMBLong-term sleep disturbances in children: a cause of neuronal lossEur J Paediatr Neurol201014538039020554229

- MaretSFaragunaUNelsonABCirelliCTononiGSleep and waking modulate spine turnover in the adolescent mouse cortexNat Neurosci201114111418142021983682

- ArchboldKHPituchKJPanahiPChervinRDSymptoms of sleep disturbances among children at two general pediatric clinicsJ Pediatr200214019710211815771

- LabergeLCarrierJLespérancePSleep and circadian phase characteristics of adolescent and young adult males in a naturalistic summertime conditionChronobiol Int200017448950110908125

- OwensJASpiritoAMcGuinnMNobileCSleep habits and sleep disturbance in elementary school-aged childrenJ Dev Behav Pediatr2000211273610706346

- PaavonenEJAronenETMoilanenISleep problems of school-aged children: a complementary viewActa Paediatr200089222322810709895

- KaneitaYOhidaTOsakiYAssociation between mental health status and sleep status among adolescents in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional surveyJ Clin Psychiatry20076891426143517915984

- Fricke-OerkermannLPlückJSchredlMPrevalence and course of sleep problems in childhoodSleep200730101371137717969471

- PeterTRobertsLWBuzduganRSuicidal ideation among Canadian youth: a multivariate analysisArch Suicide Res200812326327518576207

- MooreMMeltzerLJThe sleepy adolescent: causes and consequences of sleepiness in teensPaediatr Respir Rev200892114120 quiz 12018513671

- MercerPWMerrittSLCowellJMDifferences in reported sleep need among adolescentsJ Adolesc Health19982352592639814385

- CarskadonMAHarveyKDukePAndersTFLittIFDementWCPubertal changes in daytime sleepiness. 1980Sleep200225645346012224838

- BonnetMHArandDLWe are chronically sleep deprivedSleep199518109089118746400

- RajaratnamSMArendtJHealth in a 24-h societyLancet20013589286999100511583769

- IglowsteinIJenniOGMolinariLLargoRHSleep duration from infancy to adolescence: reference values and generational trendsPediatrics2003111230230712563055

- LemolaSSchwarzBSiffertAInterparental conflict and early adolescents’ aggression: is irregular sleep a vulnerability factor?J Adolesc20123519710521733568

- AstillRGVan der HeijdenKBVan IjzendoornMHVan SomerenEJSleep, cognition, and behavioral problems in school-age children: a century of research meta-analyzedPsychol Bull201213861109113822545685

- WongMLLauEYWanJHCheungSFHuiCHMokDSThe interplay between sleep and mood in predicting academic functioning, physical health and psychological health: a longitudinal studyJ Psychosom Res201374427127723497826

- FredriksenKRhodesJReddyRWayNSleepless in Chicago: tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school yearsChild Dev2004751849515015676

- GrobALüthiRKaiserFFlammerAMackinnonAWearingABerner Fragebogen zum Wohlbefinden Jugendlicher (BFW). [The Bern Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire for Adolescents (BFW)]Diagnostica19913716675

- OldsTBlundenSPetkovJForchinoFThe relationships between sex, age, geography and time in bed in adolescents: a meta-analysis of data from 23 countriesSleep Med Rev201014637137820207558

- RiemannDSpiegelhalderKFeigeBThe hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidenceSleep Med Rev2010141193119481481

- BaglioniCSpiegelhalderKLombardoCRiemannDSleep and emotions: a focus on insomniaSleep Med Rev201014422723820137989

- HaarioPRahkonenOLaaksonenMLahelmaELallukkaTBidirectional associations between insomnia symptoms and unhealthy behavioursJ Sleep Res2013221899522978579

- ArbusCCochenVSleep changes with agingPsychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil201081714 French [with English abstract]20215094

- LehnkeringHSiegmundRInfluence of chronotype, season, and sex of subject on sleep behavior of young adultsChronobiol Int200724587588817994343

- ThorleifsdottirBBjörnssonJKBenediktsdottirBGislasonTKristbjarnarsonHSleep and sleep habits from childhood to young adulthood over a 10-year periodJ Psychosom Res200253152953712127168

- CorbettRWMiddletonBArendtJAn hour of bright white light in the early morning improves performance and advances sleep and circadian phase during the Antarctic winterNeurosci Lett2012525214615122750209

- WehrTAThe durations of human melatonin secretion and sleep respond to changes in daylength (photoperiod)J Clin Endocrinol Metab1991736127612801955509

- KhalsaSBJewettMECajochenCCzeislerCAA phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjectsJ Physiol2003549Pt 394595212717008

- ArendtJBiological rhythms during residence in polar regionsChronobiol Int201229437939422497433

- HenseSBarbaGPohlabelnHFactors that influence weekday sleep duration in European childrenSleep201134563363921532957

- SpearLPThe adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestationsNeurosci Biobehav Rev20002441746310817843

- GangwischJEBabissLAMalaspinaDTurnerJBZammitGKPosnerKEarlier parental set bedtimes as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideationSleep20103319710620120626

- ShortMAGradisarMWrightHLackLCDohntHCarskadonMATime for bed: parent-set bedtimes associated with improved sleep and daytime functioning in adolescentsSleep201134679780021629368

- KalakNGerberMKirovRThe relation of objective sleep patterns, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances in adolescent children and their parents: a sleep-EEG study with 47 familiesJ Psychiatr Res201246101374138222841346

- BajoghliHAlipouriAHolsboer-TrachslerEBrandSSleep patterns and psychological functioning in families in northeastern Iran; evidence for similarities between adolescent children and their parentsJ Adolesc20133661103111324215957

- BrandSHatzingerMBeckJHolsboer-TrachslerEPerceived parenting styles, personality traits and sleep patterns in adolescentsJ Adolesc20093251189120719237190

- LemolaSRäikkönenKScheierMFSleep quantity, quality and optimism in childrenJ Sleep Res2011201 Pt 1122020561178

- BrandSBeckJHatzingerMHarbaughARuchWHolsboer-TrachslerEAssociations between satisfaction with life, burnout-related emotional and physical exhaustion, and sleep complaintsWorld J Biol Psychiatry201011574475420331383

- BrandSGerberMKalakNAdolescents with greater mental toughness show higher sleep efficiency, more deep sleep and fewer awakenings after sleep onsetJ Adolesc Health201454110911323998848