Abstract

Background

The current study examined the psychometric properties of the 12-item French-language version of the Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (QSU-12), a widely used multidimensional measure of cigarette craving.

Methods

Daily smokers (n=230) completed the QSU-12, the Fägerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, and items about addiction-related symptoms. Additional participants (n=40) completed the QSU-12 and the Fägerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and were assessed for expired carbon monoxide.

Results

Consistent with studies validating the English version of the scale, confirmatory factor analyses supported a two-factor solution in the French version of the scale. Good scale and subscales reliabilities were observed, and convergent validity was evidenced through relationships with dependence and addiction-related symptoms.

Conclusion

The French-language version of the QSU-12 is an adequate instrument to assess the multidimensional construct of craving in both research and clinical practice.

Introduction

Craving is an important part of the experience of people with addiction and is listed as one of the features of psychoactive substance dependence in the International Classification of DiseasesCitation1 and in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.Citation2 Likewise, dominant biopsychological models of addiction consider craving to play a core role in the maintenance of addiction.Citation3–Citation6 At the empirical level, craving is a predictor of smoking relapse,Citation7–Citation9 and its decrease contributes to the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments.Citation10,Citation11 Hence, craving assessment has considerable utility for diagnosis and clinical outcomes.Citation12

There have been numerous definitions of craving. For instance, Tiffany has suggested that craving is a subjective motivational state that encourages compulsive drug self-administration, hinders efforts to achieve abstinence, and causes a relapse following sustained drug abstinence.Citation6 While some authors have restricted the meaning of craving to the experience of a strong desire to use a drug,Citation13,Citation14 other have proposed conceptions that encompass various affective and cognitive components. Indeed, some have considered the anticipation of the drug’s consequences, the intentions to use drugs, mental images, and drug-related affects and cognitions as part of the concept of craving.Citation4,Citation15–Citation17 This latter conception highlights the multidimensional nature of craving.

Over the last two decades, many studies have evaluated craving by using a single item.Citation18–Citation21 However, such an approach limits the assessment of reliability and validity, as it restricts craving to an unidimensional construct.Citation12,Citation22 Addressing these two flaws, the Questionnaire on Smoking Urges (QSU)Citation17 is the most widely used multidimensional measure of craving for cigarettes. The 32-item English-language version of the questionnaire was originally developed to capture various aspects of craving experiences (ie, desire to smoke, anticipation of positive reinforcement, anticipation of negative reinforcement, intention to smoke). In the initial validation study, exploratory factor analysis revealed a two-factor solution. Whereas one factor was related to the anticipation of relief from negative affect or withdrawal symptoms (negative reinforcement), the other factor was linked to the intention/desire to smoke and to the anticipation of positive outcomes (positive reinforcement). This bifactorial structure has been replicated.Citation23,Citation24 Since its creation, the QSU has been translated and validated in several languages, including Spanish,Citation25 German,Citation26 and French.Citation27

Recently, various short versions of the QSU have been developed. Short versions are useful for both research and clinical purposes (given that long scales are rarely incorporated in systematic clinical screening and/or research protocols). A 12-item version (QSU-12) was proposed by Kozlowski et alCitation28 on the basis of the highest loadings. A 10-item version (QSU-10) was then proposed by Cox et alCitation29 on the basis of both factor loadings and content coverage. Moreover, some statements were reworded to avoid reversed items. Validation studies conducted on both the 10-item and the 12-item versions corroborated a two-factor structure similar to the initial version of the scale.Citation29–Citation33 Short versions of the QSU have been translated and validated in various languages: Spanish,Citation25 Portuguese,Citation34 Italian,Citation35 and Chinese.Citation36

Although this scale has not been validated into French, several studies have already used these short versions among French-speaking samples.Citation37–Citation39 However, uncertainty still abounds regarding the psychometric properties, particularly regarding the factor structure of the French short versions of the QSU. In the initial validation of the French long version of the QSU, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) demonstrated a bifactorial structure.Citation27 However, there are a number of limitations to EFA, thereby limiting the generalizability of these findings. Indeed, although EFA is a useful approach when there is an insufficient theoretical and empirical basis to specify a model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) remains necessary to test a specific hypothesis about the structure of the data and to determine whether a proposed model fits the data well. In the present study, we use the 12-item version because it comprises negatively worded items, as suggested by the recommendations of the international test development.Citation40

The aim of the current study was to examine the psychometric and structural properties of the French-language QSU-12. We thus conducted CFA and explored the internal consistency of the scale. An additional sample was recruited in order to evaluate convergent validity with expired carbon monoxide (CO). This measure allowed us to objectively quantify the degree of exposure to one of the major components of tobacco smoke.

Methods

Participants

Participants were French-speaking smokers (daily smokers who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their entire life) aged 18 years and older. They were recruited through advertisements posted in French specialized forums and research networks. Participants were invited to circulate the invitational email to their acquaintances (ie, snowball principle emailing). In order to include a maximal number of participants, data were collected via an online survey (subsample 1). The participants of an additional sample (subsample 2) filled in the questionnaires on a written survey. Subsample 2 participants were recruited within the framework of a master’s degree thesis and, in accordance with the design of that study, were instructed not to smoke in the hour prior to the data collection.

All participants gave their consent before starting the survey. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Psychology Department of the Université catholique de Louvain.

Instruments

Participants in subsample 1 were first asked about their tobacco consumption (number of cigarettes per day and time since the last cigarette was smoked). They then completed the French version of the QSU-12.Citation27 Each item was completed on a seven-point Likert-type scale from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (7). After completing the QSU-12, participants filled out the French version of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),Citation41 which is a six-item self-report questionnaire that is widely used to assess the level of tobacco dependence. Finally, six supplementary items were generated to assess 1) negative impact of tobacco smoking on daily living, 2) frequency of smoking behaviors triggered by negative emotional contexts, 3) frequency of smoking behaviors triggered by positive emotional contexts, 4) frequency of smoking behaviors associated with pleasure or excitement seeking, 5) loss of control associated with smoking, and 6) frequency of intrusive thoughts or mental images related to smoking. These items were scored using a four-point Likert scale.

The participants in the subsample 2 were first measured for expired CO with the Micro Smokerlyzer® (Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Kent, UK), after which they completed questions about their tobacco consumption, the QSU-12, and the FTND. CO is a biological marker of exposure to combustion byproducts via inhalation. When tobacco is ignited and inhaled, CO is produced and binds to hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin before being expired into the air. The half-life of CO is 2–5 hours and it is expressed in parts per million.Citation42

Data analysis

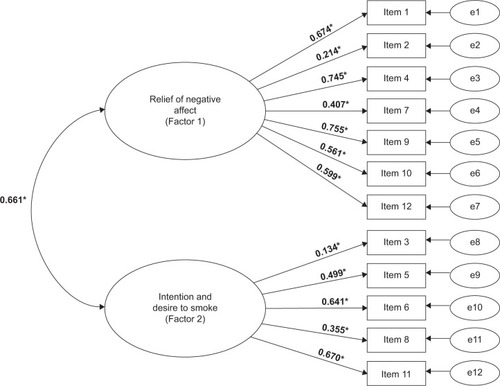

CFA were performed using SPSS AMOS 16® (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Three models were tested: Model A, a single-factor solution as suggested by Kozlowski et al;Citation28 Model B, a correlated two-factor solution as suggested by factor analysis on the French version of the QSU;Citation27 and Model C, a correlated two-factor solution derived from the English versions of the QSU.Citation17,Citation33 It should be noted that Model B and Model C differ for only one item, in that item 9 of the scale (“I have an urge for a cigarette”) loads on the relief of negative affect dimension (Factor 1) in Model B and loads on the intention and desire to smoke dimension (Factor 2) in Model C. Moreover, internal consistency and convergent validity were also evaluated.

Before performing the analysis, we conducted the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test on each item of the QSU-12. Normality was not achieved for all items (P<0.0001). Moreover, the standard method of estimation in structural equation modeling is maximum likelihood, which assumes multivariate normality of manifest variables. As noted by Byrne,Citation43 a frequent error when performing CFA is that the normality of the data is not taken into account multivariately. In our case, multivariate kurtosis was indeed high, with a Mardia’s coefficientCitation44 of 58.172 (with a cut-off value of 26.073), indicating a lack of multivariate normality. The items of the QSU-12 refer to a sample of psychological constructs that can be present or absent with varying frequency. This makes nonnormality and categorization problems likely.Citation45,Citation46 Therefore, using standard normal theory estimators with these data could produce estimation problems.

Various formulas can be applied to correct for the lack of multivariate normality when performing CFA. The most appropriate approach is to use an estimation method that makes no distributional assumptions, such as the unweighted least squares (ULS) estimation method. ULS is analogous to ordinary least squares in traditional regression.

Because the covariance matrix might not be as asymptotically distributed as chi-square with the ULS method, the chi-square test and other fit indexes based on such statistics cannot be computed and are thus not reported.Citation47 Instead, we used the following fit indices: 1) Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), 2) Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), 3) Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index (PGFI), and 4) Parsimony Ratio (PRATIO). Incremental and residual fit indices cannot be used with the ULS method.Citation47

GFI is an absolute-fit index with a corresponding adjusted version, the AGFI, developed to incorporate a penalty function for the addition of free parameters in the model.Citation48 The GFI is analogous to R2 and performs better than any other absolute-fit index regarding the absolute fit of the data.Citation49,Citation50 Both GFI and AGFI have values between 0–1, with 1 indicating a perfect fit. A value of 0.80 is usually considered as a minimum for model acceptance.Citation51

PGFI and PRATIO are parsimony-based fit measures. Absolute fit measures judge the fit of a model per se without reference to other models that could be relevant in the situation.Citation52 Parsimony-adjusted measures introduce a penalty for complicating the model by increasing the number of parameters in order to increase the fit. Usually, parsimony-fit indices are much lower than other normed-fit measures. Values larger than 0.60 are generally considered satisfactory.Citation53

The present context also requires comparing fit across different models that are not necessarily nested (ie, meaning that one model is not simply a constrained version of the other). Therefore, we also reported the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC),Citation54 the Browne–Cudeck Criterion (BCC),Citation55 and the Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI),Citation55 which are the most suited for comparison of nonnested models.Citation53 AIC, BCC, and ECVI are fit measures based on information theory. These indices are not used for judging the fit of a single model but are used in situations in which one needs to choose from several realistic but different models. These indices are a function of both model complexity and goodness of fit. For these indices, low scores refer to simple well-fitting models, whereas high scores refer to complex poor-fitting models. Therefore, in a comparison-model approach, the model with the lower score is to be preferred.

Results

In all, 270 participants were enrolled on study. Of these, 230 (85.2%) were recruited for subsample 1 and 40 (14.8%) were recruited for subsample 2. The characteristics of both subsamples are presented in .

Table 1 Participants’ characteristics

Structural validity

displays the fit indices of the three models. The three models have very good fit indices. However, Model B exhibited better fit than both Model A and Model C, as indexed by GFI and AGFI. Moreover, the AIC, BCC, and ECVI were strongly favorable to Model B (see ).

Figure 1 Path diagram depicting the correlated two-factor solution (Model B) of the short French version of the Questionnaire on Smoking Urges.

Table 2 Fit index values for the different tested models

As shown in , the standardized factor loadings of Model B were all statistically significant (P<0.01). Three items, however, showed loadings below 0.40 (ie, items 2, 3, and 8). Therefore, we also reran analyses with a new model similar to Model B but without these items. Even if a couple of fit indices tended to be better than those of previous models, this new model did not lead to any significant global improvement (GFI =0.984; AGFI =0.972; PGFI =0.569; PRATIO =0.722). In order to be consistent with the initial scale, we did not exclude these items. The items are presented in .

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency reliability, and external validity

Cronbach α coefficients for both Factor 1 (α =0.90, total score, mean 16.5±9.9) and Factor 2 (α =0.80, total score, mean 20.8±8.0) were higher than 0.75, suggesting good scale and subscale reliability.Citation56 displays the correlations between the QSU-12 subscales and other measures. Both subscales were strongly correlated with the global score. They were also positively and significantly related to cigarette consumption, FTND, loss of control (ie, difficulty in not smoking) and frequency of intrusive thoughts related to smoking behaviors. Moreover, r-to-Z Fisher score transformationCitation57 indicated that the FTND was significantly more related to Factor 1 than to Factor 2 of the QSU-12 (Z [270] =2.065, P<0.05). Moreover, the frequency of intrusive thoughts related to smoking behaviors was more significantly related to Factor 1 than to Factor 2 of the QSU-12 (Z [230] =2.384, P<0.05). Factor 1 was significantly and positively related to the negative impact of tobacco smoking on daily living, to the proneness to smoke in response to negative emotional contexts, and to the number of years of smoking. No other correlation was significant for the dimensions of the QSU-12.

Table 3 Pairwise correlations between variables of the study

Discussion

The current study examined the psychometric properties of a French version of the QSU-12. Results showed that the correlated two-factor solution derived from the long French version of the QSUCitation27 best fits the data, in comparison to the single-factor solution suggested by Kozlowski et alCitation28 as well as the correlated two-factor solution derived from the English versions of the scale.Citation17,Citation33 The first factor assesses the urgency to smoke to relieve withdrawal and/or negative affect, whereas the second factor assesses the intention and desire to smoke. A good internal consistency was also observed.

In regard to the growing development of short assessment methods for clinical and research use, some methodological guidelines have been proposed to ensure the validity of such abbreviated forms.Citation58 One of them highlights the importance of showing that a reduction in the questionnaire constitutes a trade-off between gained assessment time and induced loss of validity. We thus sought to evaluate this trade-off in the present study. On the one hand, assuming that approximately 15 seconds are necessary to fill out one item of the QSU, the completion time of the original 32-item scale is 8 minutes, whereas the short version takes only 3 minutes to complete. On the other hand, we found the QSU-12 to have a similar structure to the original French scale. Moreover, the internal reliability coefficients of the QSU-12 remained satisfactory. Finally, convergent validity was shown through the relationships with both a global scale of tobacco dependence and the items measuring addiction-related symptoms (eg, smoking in affective contexts, loss of control, intrusive thoughts, and adverse consequences in daily life). Taken together, these results support the use of the QSU-12 for a meaningful timesaving.

Relations were observed between the QSU-12 subscales and addiction symptoms. We found a correlation between both factors and loss of control (ie, difficulty in not smoking, more especially for Factor 1). This correlation is consistent with the literature, because craving has been shown to predict smoking lapses.Citation9 Both factors were also associated with the frequency of intrusive thoughts or mental images related to smoking. This finding makes sense in view of recent models that consider intrusion and mental images’ elaboration as central to craving episodes.Citation4,Citation16

Dimensions of craving were related to dependence and to the number of cigarettes smoked per day. However, dimensions of craving were not significantly related to the time since the last cigarette. In the validation of the original version of the QSU, the authors manipulated the time since the last cigarette and found an overall increase of craving for both factors of the QSU from 0–6 hours of abstinence. In the current study, the time since the last cigarette is strongly related to the mean number of cigarettes per day. The absence of correlation should thus be interpreted cautiously, as we did not manipulate it and thus did not capture the distribution of the variables when the individual engaged in a longer abstinence period than usual.Citation17 Moreover, dimensions of craving were not significantly related to CO. This absence of relation highlights the fact that craving cannot be considered as solely the result of a biological measure, such as expired CO or a potential deficit in nicotine, but as a complex and multidetermined phenomenon that also relies on psychological variables such as expectancies, beliefs, the affective state, and motivation. The multidimensional nature of craving has been developed in the elaborated intrusion theory of desire.Citation4–Citation16

Interestingly, Factor 1 (craving related to the relief of withdrawal and/or negative affect), which is closely related to dependence (as measured by the FTND), was the only dimension positively associated with the negative impact of tobacco on daily life, with the frequency of smoking triggered by negative emotional contexts and with the smoking history. In other words, high scores on this dimension characterized more-dependent smokers who reported stronger experience of the negative impact of tobacco, more frequent smoking in response to negative emotional contexts, and a longer smoking history. In contrast, Factor 2 (intention and desire to smoke), was less related to problematic outcomes (eg, no relation with negative impact in the daily life, relations of smaller amplitudes with dependence symptoms and lack of control). Accordingly, this factor may represent a type of craving, less intense and more focused on positive reinforcement (as reflected by items 3 and 8), likely to be experienced by smokers with low dependence levels and who initiated smoking more recently.

It is worth noting that in contrast with analyses realized on the English version of the QSU and consistent with those related to the French version, item 9 (“I have an urge for a cigarette”) loaded on Factor 1. This is due to an inaccurate translation of this item by Guillin et alCitation27 when they developed the French QSU. Indeed, the word “urge” has been translated in French in a way that suggests an “urgent need” rather than a “strong desire”. Thus, the words used in this translation seem more closely related to the anticipation of relief of discomfort as compared with the words used in the English version that are more tightly related to the anticipation of positive outcomes.

A first limitation to this study is that no information was collected regarding the potential motivation for smoking cessation and previous quit attempts. In the same vein, we did not collect any information regarding potential comorbid psychiatric disorders (eg, alcohol-dependence, pathological gambling, anxiety), thereby limiting the generalizability of the present findings. A second limitation is that our sample was composed of relatively low smokers (with regard to the FTND score). However, our results suggest that the more the participants have high FTND scores, the more the experience elevated levels of craving, especially on the relief from negative affect dimension. Our study might thus underestimate mechanisms that are more inherent to high levels of craving. A third limitation is that three items exhibit loadings lower than 0.40. Even if the suppression of those items did not lead to any important change in the present sample, future studies should further examine whether these items provide enough information. One interesting way would be the use, among a new sample of smokers, of an item-analysis approach modeling the probability of a specified item’s response through logistic functions of the difference between the person and item parameters, such as those mathematical approaches derived from Rash modelCitation59 or artificial neural networks.Citation60 Finally, we did not manipulate the time lag between the last cigarette and the completion of the questionnaires. This would have allowed capturing the transient and changing nature of craving across time.Citation12,Citation61 Future studies should further examine this question.

On the whole, the current study showed that the QSU-12 is a useful instrument for assessing the multidimensional construct of cigarette craving. The time saved thanks to the item-number reduction improves the clinical and research feasibility of this tool.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Arnaud Carré and all the members of the Groupe de Réflexion en Psychopathologie Cognitive (GREPACO) for their help in disseminating the study protocol. We would also like to thank Melissa Morales-Duarte for her help in data collection and the members of the Laboratory for Experimental Psychopathology for their useful comments on a preliminary draft of the article.

Supplementary material

Table S1 QSU-12 items

Disclosure

This work has been partly supported by Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium) and by a grant (grant number FC 78142) from the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research (awarded to Alexandre Heeren). These funding bodies did not exert any editorial direction or censorship on any part of this article. All authors report no competing financial interests or potential conflicts of interest, and no financial relationships with commercial interests. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationThe ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic GuidelinesGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization1992

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edWashington, DCAmerican Psyciatric Publishing2013

- DrummondDCTheories of drug craving, ancient and modernAddiction2001961334611177518

- KavanaghDJAndradeJMayJImaginary relish and exquisite torture: the elaborated intrusion theory of desirePsychol Rev2005112244646715783293

- RobinsonTEBerridgeKCIncentive-sensitization and addictionAddiction200196110311411177523

- TiffanySTA cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processesPsychol Rev19909721471682186423

- FergusonSGShiffmanSGwaltneyCJDoes reducing withdrawal severity mediate nicotine patch efficacy? A randomized clinical trialJ Consult Clin Psychol20067461153116117154744

- KillenJDFortmannSPCraving is associated with smoking relapse: findings from three prospective studiesExp Clin Psychopharmacol1997521371429234050

- ShiffmanSEngbergJBPatyJAA day at a time: predicting smoking lapse from daily urgeJ Abnorm Psychol199710611041169103722

- FranklinTWangZSuhJJEffects of varenicline on smoking cue–triggered neural and craving responsesArch Gen Psychiatry201168551652621199958

- HartwellKJLemattyTMcRae-ClarkALGrayKMGeorgeMSBradyKTResisting the urge to smoke and craving during a smoking quit attempt on varenicline: results from a pilot fMRI studyAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse2013392929823421569

- TiffanySTWrayJMThe clinical significance of drug cravingAnn N Y Acad Sci2012124811722172057

- BrandonTHWetterDWBakerTBAffect, expectancies, urges, and smoking: do they conform to models of drug motivation and relapse?Exp Clin Psychopharmacol1996412936

- KozlowskiLTWilkinsonDAUse and misuse of the concept of craving by alcohol, tobacco, and drug researchersBr J Addict198782131453470042

- Cepeda-BenitoAHenryKGleavesDHFernandezMCCross-cultural investigation of the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges in American and Spanish smokersAssessment200411215215915171463

- MayJAndradeJPanabokkeNKavanaghDImages of desire: cognitive models of cravingMemory200412444746115493072

- TiffanySTDrobesDJThe development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urgesBr J Addict19918611146714761777741

- DawkinsLPowellJHWestRPowellJPickeringAA double-blind placebo controlled experimental study of nicotine: I – effects on incentive motivationPsychopharmacology (Berl)2006189335536717047930

- HaasovaMWarrenFCUssherMThe acute effects of physical activity on cigarette cravings: systematic review and meta-analysis with individual participant dataAddiction20131081263722861822

- Janse Van RensburgKTaylorABenattayallahAHodgsonTThe effects of exercise on cigarette cravings and brain activation in response to smoking-related imagesPsychopharmacology (Berl)2012221465966622234380

- UssherMAveyardPManyondaIPhysical activity as an aid to smoking cessation during pregnancy (LEAP) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trialTrials20121318623035669

- RosenbergHClinical and laboratory assessment of the subjective experience of drug cravingClin Psychol Rev200929651953419577831

- DaviesGMWillnerPMorganMJSmoking-related cues elicit craving in tobacco “chippers”: a replication and validation of the two-factor structure of the Questionnaire of Smoking UrgesPsychopharmacology (Berl)2000152333434211105944

- WeinbergerAHReutenauerELAllenTMReliability of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale, and Tiffany Questionnaire for Smoking Urges in smokers with and without schizophreniaDrug Alcohol Depend2007862–327828216876968

- Cepeda-BenitoAReig-FerrerADevelopment of a brief questionnaire of smoking urges – SpanishPsychol Assess200416440240715584801

- MüllerVMuchaRFAckermannKPauliPDie erfassung des cravings bei rauchern mit einer deutschen version des “Questionnaire on smoking urges” (QSU-G) [The assessment of craving in smokers with a German version of the “Questionnaire on Smoking Urges” (QSU-G)]Z Klin Psychol Psychother2001303164171 German

- GuillinOKrebsMOBourdelMCOlieJPLooHPoirierMFValidation of the French translation and factorial structure of the Tiffany and Drobes Smoking Urge QuestionnaireL’Encephale19992662731 French

- KozlowskiLTPillitteriJLSweeneyCTWhitfieldKEGrahamJWAsking questions about urges or cravings for cigarettesPsychol Addict Behav1996104248260

- CoxLSTiffanySTChristenAGEvaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settingsNicotine Tob Res20013171611260806

- CappelleriJCBushmakinAGBakerCLMerikleEOlufadeAOGilbertDGMultivariate framework of the Brief Questionnaire of Smoking UrgesDrug Alcohol Depend2007902–323424217482773

- ClausiusRLKrebillRMayoMSEvaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges in Black light smokersNicotine Tob Res20121491110111422241828

- TollBAKatulakNAMcKeeSAInvestigating the factor structure of the Questionnaire on Smoking Urges-Brief (QSU-Brief)Addict Behav20063171231123916226843

- TollBAMcKeeSAKrishnan-SarinSO’malleySSRevisiting the factor structure of the questionnaire on smoking urgesPsychol Assess200416439139515584799

- AraujoRBOliveiraMDSMoraesJFDPedrosoRSPortFDe CastroMDGTDValidação da versão brasileira do Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief [Validation of the Brazilian version of Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief]Revista de Psiquiatria Clinica2007344166175 Portuguese

- TeneggiVOprandiNMilleriSVerifica della validità esteriore e del contenuto della versione italiana di tre questionari su craving e astinenza da fumo di sigarette [Assessment of face and content validity of the Italian version of three questionnaires on cigarette smoke craving and withdrawal]Giornale di Psicopatologia200174378386 Italian

- YuXXiaoDLiBEvaluation of the Chinese versions of the Minnesota nicotine withdrawal scale and the questionnaire on smoking urges-briefNicotine Tob Res201012663063420498226

- BerlinISingletonEGNicotine dependence and urge to smoke predict negative health symptoms in smokersPrev Med200847444745118602945

- BillieuxJGayPRochatLKhazaalYZullinoDVan der LindenMLack of inhibitory control predicts cigarette smoking dependence: evidence from a non-deprived sample of light to moderate smokersDrug Alcohol Depend20101121–216416720667667

- BillieuxJVan der LindenMCeschiGWhich dimensions of impulsivity are related to cigarette craving?Addict Behav20073261189119916997490

- FabrigarLRWegenerDTMacCallumRCStrahanEJEvaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological researchPsychol Methods199943272299

- HeathertonTFKozlowskiLTFreckerRCFagerströmKOThe Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance QuestionnaireBr J Addict1991869111911271932883

- BenowitzNLThe use of biologic fluid samples in assessing tobacco smoke consumptionNIDA Res Monogr1983486266443145

- ByrneBMStructural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/WindowsThousand Oaks, CASage Publications, Inc1994

- MardiaKVApplications of some measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis in testing normality and robustness studiesSankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics197436Series B, Pt 2115128

- McDonaldRPHoMHPrinciples and practice in reporting structural equation analysesPsychol Methods200271648211928891

- HeerenADouilliezCPeschardVDebrauwereLPhilippotPValidité transculturelle du Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire: adaptation et validation auprès d’un échantillon francophone [Cross-cultural consistency of the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire: adaptation and validation in a French-speaking sample]Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée2011613147151 French

- BrowneMWCovariance structuresHawkinsDMTopics in Applied Multivariate AnalysisCambridge, UKCambridge University Press198272141

- JöreskogKGSörbomDLISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Applications2nd edChicago, ILSPSS Inc1989

- HoyleRHPanterATWriting about structural equation modelsHoyleRHStructural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and ApplicationsThousand Oaks, CASage Publications, Inc1995158176

- MarshHWBallaJRMcDonaldRPGoodness-of-fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis: the effects of sample sizePsychol Bull19881033391410

- ColeDAUtility of confirmatory factor analysis in test validation researchJ Consult Clin Psychol19875545845943624616

- JamesCRMulaikSABrettJMCausal Analysis: Assumptions, Models and DataBeverley Hills, CASage Publications, Inc1982

- BlunchNJIntroduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS and AMOSLondon, UKSage Publications Ltd2008

- AkaikeHFactor analysis and AICPsychometrika198752317332

- BrowneMWCudeckRSingle sample cross-validation indices for covariance structuresMultivariate Behav Res1989244445455

- NunnallyJCPsychometric Theory2nd edNew York, NYMcGraw-Hill Inc1978

- SteigerJHTests for comparing elements of a correlation matrixPsychol Bull1980872245251

- SmithGTMcCarthyDMAndersonKGOn the sins of short-form developmentPsychol Assess200012110211110752369

- RaschGProbabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests Expanded edChicago, ILThe University of Chigago Press1980

- ShuZHensonRWillseJUsing neural network analysis to define methods of DINA model estimation for small sample sizesJ Classif2013302173194

- TiffanySTWarthenMWGoedekerKCThe functional significance of craving in nicotine dependenceNebr Symp Motiv20095517119719013944