Abstract

Objective

To highlight which demographic, familial, premorbid, clinical, therapeutic, rehabilitative, and assistance factors were related to dual diagnosis, which, in psychiatry, means the co-occurrence of both mental disorder and substance use in the same patient.

Methods

Our sample (N=145) was chosen from all outpatients with a dual diagnosis treated from January 1, 2012 to July 31, 2012 by both the Mental Health Service and the Substance Use Service of Modena and Castelfranco Emilia, Italy. Patients who dropped out during the study period were excluded. Demographic data and variables related to familial and premorbid history, clinical course, rehabilitative programs, social support and nursing care, and outcome complications were collected. The patients’ clinical and functioning conditions during the study period were evaluated.

Results

Our patients were mostly men suffering from a cluster B personality disorder. Substance use was significantly more likely to precede psychiatric disease (P<0.001), and 60% of the sample presented a positive familial history for psychiatric or addiction disease or premorbid traumatic factors. The onset age of substance use was related to the period of psychiatric treatment follow-up (P<0.001) and the time spent in rehabilitative facilities (P<0.05), which, in turn, was correlated with personality disorder diagnosis (P<0.05). Complications, which presented in 67% of patients, were related to the high number of psychiatric hospitalizations (P<0.05) and professionals involved in each patient’s treatment (P<0.05). Males more frequently presented familial, health, and social complications, whereas females more frequently presented self-threatening behavior (P<0.005).

Conclusion

It was concluded that the course of dual diagnosis may be chronic, severe, and disabling, requiring many long-term therapeutic and rehabilitative programs to manage various disabilities.

Introduction

In psychiatry, the term “dual diagnosis” and other interchangeable terms (eg, comorbidity, co-occurring illnesses, concurrent disorders, dual disorder, double trouble) mean the co-occurrence of both a mental health disorder and substance use in the same patient.Citation1,Citation2 The occurrence of dual diagnosis is quite common: Regier et alCitation3 reported that 44% of alcohol abusers and 64.4% of illegal substance abusers suffered from a major mental disorder, whereas Kessler et alCitation4,Citation5 found that persons affected by alcohol or illegal drug dependence presented a mental disorder 4.1 times and 4.9 times more frequently, respectively, than non–alcohol-dependent people.

Other studies have shown that 56% of patients suffering from a substance use disorder had a mental disorder at the same timeCitation6 and that from 18.5% to 50.0% of patients with a substance use disorder had received psychiatric treatment during their lifetimes.Citation7–Citation9

Among dual-diagnosis patients, substance-use disorders range from single drug abuse to cocktails of substances, whereas mental health problems include both a wide range of disorders, from those defined as “high-prevalence and low-impact therapeutic”, such as anxiety and depression, to those defined as “low prevalence, high-impact therapeutic”, such as psychosis and major mood disorders. Although the “low impact” group is the most represented among dual-diagnosis patients, the “high impact” group, even if smaller, requires more intensive and expensive treatment programs.Citation10 The co-occurrence of the abovementioned disorders increases the severity of symptoms and difficulty of treatment, with worse physical, psychological, and social outcomes.Citation10 The clinical and rehabilitative needs of dual-diagnosis patients can be extremely different and polymorphic, depending on the level of their functioning, which is usually conditioned by pathological behavior and poor therapeutic compliance.Citation11,Citation12

Neurobiological models attribute the key role in the development of addiction to the brain’s reward system via the dopaminergic mesocorticolimbic pathway.Citation13 The vulnerability to addiction development is frequently associated with genetic factors and personality traits. Recent studies highlighted that both alcohol-dependent and opiate-dependent patients have common genetic variants in dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin-transporter–linked promoter region associated with higher frequency to novelty-seeking personality traits.Citation14 Impulsivity, perhaps the most widely studied personality trait in the addiction literature, represents a predictor of future problems with substance use, due to its biologically-based link to additive core processes,Citation15 and is closely associated with alcohol use, especially in individuals with poor working-memory capacity.Citation16

Personality disorders are considered the most important predictors of treatment outcome in drug abusers. Borderline personality disorder is associated with high lifetime rates of substance abuse as well as higher-than-expected rates of charges for various drug-related crimes and criminal behavior.Citation17 The comorbidity between cocaine dependence and personality disorders from Clusters B and C is associated with executive-function deficits.Citation18 The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsCitation19 highlighted that individuals with drug use disorder were 2.2 times more likely to present a comorbid personality disorder. Some studies have identified the Cluster B antisocial and borderline personality disorders as most prevalent across various types of substance abusers.Citation20,Citation21

Many researchers found that individuals with dual diagnosis had high rates of a positive family history for substance use and/or psychiatric diseases, which could impact the severity and consequences of dual diagnosis.Citation22,Citation23 Other studies evidenced that vulnerability to substance abuse increased among individuals with mental illness who were victimized during childhoodCitation24,Citation25 and that this relationship induced a range of poor outcomes, including earlier onset and longer duration of substance abuse, worse physical health, and more interpersonal problems.Citation26,Citation27

The relationship between substance use and mental disorders has long been debated in order to evidence which of the two diseases could most condition the onset of the other. In adolescents and young adults with a first psychotic episode, co-occurring substance use was reported in 74% of all cases and was associated with limited response to treatment, decreased medication adherence, and worsened illness course.Citation28,Citation29 Psychosis and onset of substance use are often linked: one-third of patients experienced their first psychotic episode before the age of 19 years, and adolescence represents the peak time period for use and experimentation with alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit substances, the capability of which to induce psychotic symptoms has been well established.Citation30–Citation33 In particular, cannabis may represent a significant risk factor for the development of psychotic illness in vulnerable individuals.Citation30–Citation34 Schizophrenia patients have a higher risk for substance abuse due to degenerating cognitive abilities and disadvantageous life circumstances (“cumulative risk factor hypothesis”) or due to a need to reduce their symptoms and to offset the side effects of antipsychotic medication (“self-medication hypothesis”).Citation35,Citation36

The co-occurrence of mood and substance use disorders is common and is clinically more severe and more difficult to treat, with considerable psychosocial disability and increased utilization of health care resources, including psychiatric hospitalizations.Citation37–Citation39 The lifetime prevalence rate of all bipolar disorders and substance use disorders is 47.3% and, in particular, for bipolar I and substance use disorders is 60.3%.Citation40–Citation42 Comorbid substance use disorder is frequent in major depression, with lifetime rates of 40.3% for alcohol use and 17.2% for all other associated substance use disorders.Citation43 Comorbidity between anxiety and substance use disorders is pervasive in the US population.Citation43,Citation44 Because mood symptoms may precede or be precipitated by drug and alcohol dependence, most authors hypothesize that common risk factors for both diseases, such as stressful events,Citation45 psychological trauma, and genetic vulnerability, could lead to co-occurring expression.Citation46,Citation47

The aims of the current study were to analyze the clinical course, outcome complications, and assistance-care needs of a sample of dual-diagnosis patients treated by both the Mental Health Service (MHS) and the Substance Use Service (SUS) of Modena and Castelfranco Emilia, Italy, and to highlight which demographic, familial, premorbid, clinical, therapeutic, rehabilitative, and/or nursing-care factors are related to dual diagnosis and can condition its course.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This study, conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice, was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of Azienda USL di Modena. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the beginning of treatments on both of the services after a discussion about treatment and utilization of their demographic and clinical data.

Sample

Our sample was chosen from all outpatients (N=175) with dual diagnosis (according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]Citation48 in use in our department), treated by both MHS and SUS (catchment area of approximately 250,000 inhabitants) during the period January 1, 2012 to July 31, 2012. After excluding 30 dual-diagnosis patients treated by both services who voluntarily discontinued outpatient treatment during the study period (ie, did not return for subsequent appointments), our sample consisted of 145 dual-diagnosis patients. From the services’ medical records, we retrospectively collected demographic data and the variables shown in for our sample.

Table 1 The variables collected in our sample

Variables

Familial and premorbid history

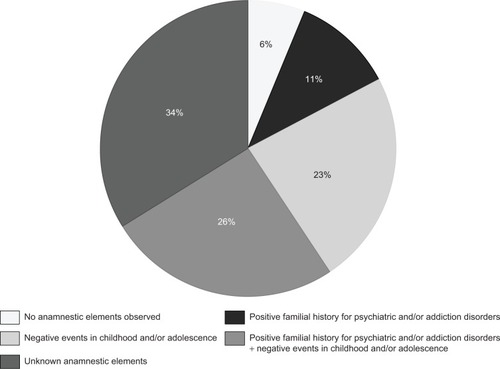

Family history of psychiatric disorders and/or substance abuse and stressful and/or negative events experienced during childhood or adolescence were analyzed in order to evaluate inherited or acquired predisposal conditions to dual-diagnosis development ().

Clinical course

The following variables were chosen in order to identify the clinical complexity of the dual disorder: onset age of substance abuse and psychiatric illness, follow-up period of treatment at MHC and SUS, the kind of substance abused (both at the onset of illness and during the study period), number of psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric diagnoses according to the ICD-9-CM,Citation48 psychopharmacological treatments, therapies prescribed as substance replacement (eg, methadone, buprenorphine) and/or as an adversative drug (disulfiram), and psychotherapy method used (individual supportive, supportive group, or other kind) ().

Rehabilitative programs, social support, and professional staffing

The rehabilitative programs were assessed through the months spent either in therapeutic communities or in psychiatric facilities. This represented, in our opinion, the time required to relearn the necessary basic skills to live autonomously. The social service activities consisted of all supportive interventions, such as protected job placement, house collocation, or economic assistance, required by patients due to their social maladaptive situation (). The level of nursing care was evaluated through the number of professionals involved in each patient’s treatment, since the complexity of care activities could range from drug administration or collection of samples for toxicological tests to more complex activities, such as educational and relational approaches for patients with severely impaired functioning ().

Outcome complications

The following complications related to dual diagnosis were analyzed: work problems (eg, unemployment, frequent job change, economic crisis), family problems (eg, separation, family abandonment, loss of parental authority), health problems (eg, hepatitis C virus, HIV infection, alcoholic liver disease, epilepsy), legal problems (eg, revoked driving license, crimes related to substance use or psychiatric illness, detention in prison), self-injurious behavior (self-harm, suicide attempts, dangerous behavior), social problems (eg, isolation, institutional dependence, social drift, prostitution, homelessness) ().

Clinical tests

In order to assess clinical and functional aspects of our sample, we collected the Global Impression Scale-Severity (CGI-S)Citation49 and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)Citation50 scores collected during the first psychiatric evaluation at MHS and recorded in patients’ clinical charts. We asked the MHS psychiatrist of each dual-diagnosis patient to evaluate her/his clinical condition during the study period by means of the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Improvement (CGI-I)Citation48 and GAF, in order to compare it to the patients’ clinical situation at the first psychiatric treatment ().

Statistical analysis

Data from the 145 patients in our final sample were statistically analyzed (descriptive statistics, Student’s t-test, chi-square test, Spearman correlations, simple and multiple linear and logistic regression, survival analyses) using the STATA software program.Citation51

Results

Our sample included 95 males (65.52%) and 50 females (34.48%), with 94% Italians (n=136). The average age in our sample was 44 years for men and 45 years for women.

Familial and premorbid history

We were not able to obtain reliable information for 34% of our sample as no familial and/or premorbid elements of anamnesis had been reported in the medical records. We observed that most patients presented a premorbid history (), including familial psychiatric illness or substance use (11%), stressful life events occurring in childhood or adolescence (23%), or both of these conditions (26%). We could not correlate these factors with any other variables analyzed. Only 6% of our patients did not report any premorbid factor.

Clinical course

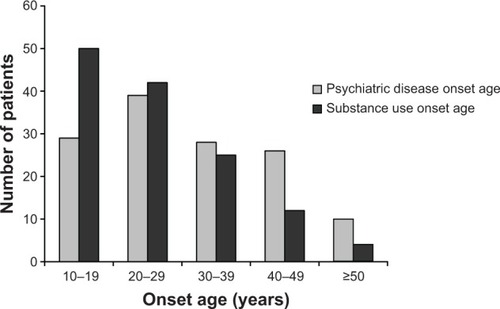

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) onset age of substance use disorders diagnosed according to ICD-9-CMCitation48 (24.83±10.06 years) was earlier than psychiatric illness onset age (30.47±12.10 years) and the difference between the two age groups was statistically significant (Student’s t-test, t=4.6441, df =128, P<0.001). We evidenced that the positive correlation between the onset age of substance use and psychiatric illness was statistically significant (Spearman’s rho =0.4522, P<0.001; simple linear regression, standard error [SE] =0.0862, 95% confidence interval [CI] =0.3251–0.6662, df=128, P<0.001). As shown in , this trend was inverted during the last three decades of life, where psychiatric disease onset preceded substance use.

shows the onset age of pathological substance use, diagnosed according to ICD-9-CM.Citation48 Onset age was statistically significantly related to the kind of abuse substance (simple linear regression, SE =0.3615, 95% CI =0.1865–1.6163, df=137, P<0.05). As the survival analysis evidenced, the onset age of psychiatric diseases was conditioned by the kind of abuse substance (log-rank test, hazard ratio [HR] =0.9078, SE =0.0408, 95% CI =0.8313–0.9914, df=137, P<0.05), whereas the onset age of substance use was related to the time spent in therapeutic communities or psychiatric facilities (log-rank test, HR =1.1962, SE =0.1020, 95% CI =1.012–1.4140, df=119, P<0.05) and to the follow-up period of psychiatric treatment in the MHS (log-rank test, HR =1.1399, SE =0.0304, 95% CI =1.0818–1.2011, df=119, P<0.001).

Table 2 Onset and current substance(s) of abuse and mean age of use onset per substance (n=145)

We did not find any statistically significant difference between substances used at the onset and those used during the study period, although the percentage of patients who used opiates was almost halved during the period of this study ().

We found that personality disorder was the most frequent diagnosis (38.62%), followed by bipolar disorder and schizophrenic psychosis, each representing 21.38% of the sample (); psychiatric diagnosis was not statistically significant related to either a specific kind of substance use or a cocktail of substances.

Table 3 Psychiatric diagnosis, sex, and onset age of psychiatric diseases in our sample

Sex was significantly correlated to psychiatric diagnoses (Pearson χ2=13.2134, df=144, P<0.05): in our sample, schizophrenic psychosis was much more frequent in males (). Our male patients were more frequently treated with neuroleptic drugs (Pearson χ2=17.5814, df=144, P<0.005) and more frequently presented familial, health, and social complications (Pearson χ2=19.3113, df=144, P<0.005), whereas females more often presented self-threatening behavior ().

Table 4 Complications and psychopharmacologic therapies in male and female patients

The follow-up period () of SUS treatment was statistically significantly correlated with the onset age of both psychiatric diseases (multiple linear regression, SE =0.0648, 95% CI =0.0546–0.3113, df=120, P<0.05) and addiction disorder (multiple linear regression, SE =0.0719, 95% CI =−0.4983 to −0.2134, df=120, P<0.001), whereas the follow-up period of MHS treatment () was related only to the onset age of psychiatric diseases (multiple linear regression, SE =0.06367, 95% CI =−0.2937 to −0.0416, df=125, P<0.001).

Table 5 Hospitalizations, community treatments, pharmacotherapies, rehabilitation, and nursing care in dual-diagnosis patients

Rehabilitative programs, social support, and professional staffing

We found a statistically significant correlation between time spent in communities and/or in residential facilities () and psychiatric diagnosis (multiple linear regression, SE =0.0964, 95% CI =0.0607–0.4420; df=144; P<0.01), in particular for personality disorders (multiple linear regression, SE =0.8933; 95% CI =−0.1947 to −3.3376; df=144; P<0.05), but not with a specific kind of substance. Most patients (77%) were involved in a rehabilitative or social program and 75% of patients were assisted by one (32%) or more nurses (43%) involved in their treatment ().

Outcome complications

Only 33% of patients did not present any complications; the remaining 67% suffered from many different problems, in similar percentages, as shown in . As mentioned on page 5, 3rd paragraph, the kinds of problems were different for males and females. The occurrence of complications was statistically significantly related, with a positive correlation, both to the number of psychiatric hospitalizations (Spearman’s rho =0.1721, P<0.05; multiple logistic regression, OR =1.7859, SE =0 .5061, 95% CI =1.0248–3.1121, df=106, P<0.05) and to the number of professionals involved in each patient’s treatment (Spearman’s rho =0.2403, P<0.005; multiple logistic regression, OR =4.3604, SE =2.6403, 95% CI =1.3307–14.2872, df=106, P<0.05).

Clinical tests

The mean ± SD GCI-S score (4.89±1.41) was statistically significantly related only to the kind of substance used, in particular alcohol (linear regression, SE =0.6270, 95% CI =0.0644–2.5490, df=118, P<0.05) and cocktails of different substances (linear regression, SE =0.3484, 95% CI =0.2116–1.5922, df=118, P<0.05), as described in .

The mean ± SD GCI-I score (3.51±1.53) was statistically significantly related only to psychotherapy activities, particularly to group psychotherapy (multiple linear regression, SE =0.5759, 95% CI =−2.7887 to −0.4957, df=97, P<0.05).

The mean ± SD GAF score obtained during the study period (56.42±20.67) was statistically significantly different from the mean GAF score at the beginning of psychiatric treatment (44.44±18.82) (Student’s t-test, t=−7.0467, df=251, P<0.001) and was statistically significantly related to the number of psychiatric hospitalizations (multiple linear regression, SE =1.8065, 95% CI =−7.882164 to −0.6933576, df=97, P<0.05), with a negative correlation (Spearman’s rho =−0.2106, P<0.05).

Discussion

The higher frequency of male patients in our sample corresponds to the sex distribution in the SUS (71% males and 29% females), but our dual-diagnosis patients were older on average (44 years) than all other patients of the SUS (36 years), suggesting that the occurrence of dual diagnosis needed many years to develop completely.

In accordance with most recent studies,Citation25,Citation52 we noticed a high prevalence of psychiatric illness and/or addiction disorders in the family histories of our patients and a much higher occurrence of multiple stressful life events during their childhood and adolescence, which could represent a sort of inherited or acquired vulnerability to the development of both diseases.

Because substance use preceded psychiatric disease in our sample, we could infer that addiction represents the pathological factor that had strongly conditioned mental disease development, but we have to underline, in accordance with the literature,Citation10 that a preclinical stage of psychiatric disorders, not recorded in medical charts, could have made people more vulnerable to drug abuse or have induced them to use substances as a sort of self-therapy. Nevertheless, the two disorder onsets were so tightly interconnected as to lead us to hypothesize common risk factors for both diseases. In particular, the kind of substance abuse conditioned the onset age of psychiatric and addiction disorders, as most authors have already evidenced:Citation12,Citation53 alcohol abuse began later and was most often related to psychiatric disorder development, whereas cannabis use was closely related to younger age and, probably, to psychosis onset. On the other hand, the chronicity and severity of psychiatric diseases affected addiction development, which could induce a sort of social drift. The patients suffering from Cluster B personality disorders, which was the most frequent psychiatric diagnosis as also reported by other studies,Citation54,Citation55 spent a longer time than other patients either in psychiatric communities or residential facilities, probably because of their greater difficulties in social and relational adaptation.

Our sample included “severely ill” patients as attested to by both the high percentage (76%, as shown in ) of patients admitted at least once to a psychiatric hospital during the illness course observed and the CGI-S mean score, which was in turn conditioned by the kind of abuse substance, in particular by alcohol. The indicators of our patients’ severity were represented by the frequent psychiatric hospitalizations, the presence of several complications, and the high number of professionals involved in the treatment of each patient.

The complications observed were different in males and females: familial, economic, and social maladaptive situation with legal problems were higher in males, whereas females were more vulnerable to self-threatening behaviors and depressive conditions, as the more frequent prescription of antidepressant drugs evidenced. Moreover, males were more frequently treated with antipsychotic drugs, probably due to altered behavior as well as to the higher number of male schizophrenia patients. These observations led us to infer a different evolution of dual diagnosis: an antisocial drift in male patients and a depressive course in female patients.

Outpatient services had to provide long-term supportive therapies, which were conditioned in both services by the onset age of substance use. This data further suggests that dual diagnosis represented a negative prognostic factor because it induced chronicity and reduced the efficacy of therapeutic programs.

We observed that approximately 65% of patients in our sample were involved in psychotherapy activities, which were related to improvement assessed by the CGI-I scale. In spite of the chronic course of illness and the complications recorded, the final GAF scale scores were statistically significantly higher than the initial ones, suggesting that patients’ functioning had improved after long-term treatment.

Conclusion

The course of dual diagnosis in our sample was chronic, severe, and disabling and required many long-term therapeutic and rehabilitative programs to deal with various disabilities. Health professionals involved in therapy, assistance, and rehabilitation of dual-diagnosis patients should clearly keep in mind the relationship between substance abuse and mental disorder in order to focus on screening tools, damage-reducing interventions, and continuous assistance/support.

Advantages and limits

Our study, although limited by its retrospective design, highlighted a sample of patients representative of both Mental Health Service and Substance Use Service populations over a relatively long follow-up period. The sample was selective since it contained only those in treatment and cannot necessarily be generalized to other populations of dual-diagnosis patients. The variables collected were not exhaustive, but sufficiently representative of dual-diagnosis clinical issues.

Implications for future

Additional studies are necessary to better explore dual-diagnosis topics. In particular, both of the conditions fostering the development of dual diagnosis and its long-term follow-up, differentiated for kind of abuse substance and type of psychiatric disease, should be investigated in larger and more-focused samples in order to identify the patients’ vulnerabilities and to improve treatment programs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BremsCJohnsonMEWellsRSBurnsRKlettiNRates and sequelae of the coexistence of substance use and other psychiatric disordersInt J Circumpolar Health200261322424412369112

- RiglianoPDoppia diagnosi. Tra tossicodipendenza e psicopatologia [Dual diagnosis. Between drug abuse and psychopathology]Milan, ItalyCortina Raffaello2004 Italian

- RegierDAFarmerMERaeDSComorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) StudyJAMA199026419251125182232018

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562659360215939837

- KesslerRCChiuWTDemlerOMerikangasKRWaltersEEPrevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562661762715939839

- MaremmaniIZolesiOAgliettiMCastrogiovanniPDisturbi correlati a sostanze [Disorders related to substance]CassanoGBPancheriPPavanLTrattato Italiano di Psichiatria2nd edMilan, ItalyMasson199913521377 Italian

- HorsfallJClearyMHuntGEWalterGPsychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empirical evidenceHarv Rev Psychiatry2009171243419205964

- RushBKoeglCJPrevalence and profile of people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders within a comprehensive mental health systemCan J Psychiatry2008531281082119087479

- SterlingSChiFHinmanAIntegrating care for people with co-occurring alcohol and other drug, medical, and mental health conditionsAlcohol Res Health201133433834923580018

- CanawayRMerkesMBarriers to comorbidity service delivery: the complexities of dual diagnosis and the need to agree on terminology and conceptual frameworksAust Health Rev201034326226820797355

- MunroIEdwardKLMental illness and substance use: an Australian perspectiveInt J Ment Health Nurs200817425526018666908

- PadwaHLarkinsSCrevecoeur-MacphailDAGrellaCEDual diagnosis capability in mental health and substance use disorder treatment programsJ Dual Diagn20139217918623687469

- KoobGFThe neurobiology of addiction: a neuroadaptational view relevant for diagnosisAddiction2006101Suppl 1233016930158

- WangTYLeeSYChenSLAssociation between DRD2, 5-HTTLPR, and ALDH2 genes and specific personality traits in alcohol-and opiate-dependent patientsBehav Brain Res201325028529223685324

- GulloMJLoxtonNJDaweSImpulsivity: Four ways five factors are not basic to addictionAddict Behav Epub2014116

- EllingsonJMFlemingKAVergésABartholowBDSherKJWorking memory as a moderator of impulsivity and alcohol involvement: Testing the cognitive-motivational theory of alcohol use with prospective and working memory updating dataAddict Behav Epub2014123

- SansoneRAWattsDAWiedermanMWBorderline personality symptomatology and legal charges related to drugsInt J Psychiatry Clin Pract201418215015224059849

- Albein-UriosNMartinez-GonzalezJMLozano-RojasOVerdejo-GarciaAExecutive functions in cocaine-dependent patients with Cluster B and Cluster C personality disordersNeuropsychology2014281849024219612

- ConwayKPComptonWStinsonFSGrantBFLifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsJ Clin Psychiatry200667224725716566620

- AngresDBologeorgesSChouJA two year longitudinal outcome study of addicted health care professionals: an investigation of the role of personality variablesSubst Abuse20137496023531922

- KruegerRFHicksBMPatrickCJCarlsonSRIaconoWGMcGueMEtiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrumJ Abnorm Psychol2002111341142412150417

- MroziewiczMTyndaleRFPharmacogenetics: a tool for identifying genetic factors in drug dependence and response to treatmentAddict Sci Clin Pract201052172922002450

- WilsonCSBennettMEBellackASImpact of family history in persons with dual diagnosisJ Dual Diagn201391303823538687

- ManiglioRThe impact of child sexual abuse on health: a systematic review of reviewsClin Psychol Rev200929764765719733950

- WilsonDRHealth consequences of childhood sexual abusePerspect Psychiatr Care2010461566420051079

- SchäferIFisherHLChildhood trauma and psychosis – what is the evidence?Dialogues Clin Neurosci201113336036522033827

- SideliLMuleALa BarberaDMurrayRMDo child abuse and maltreatment increase risk of schizophrenia?Psychiatry Investig2012928799

- Di LorenzoRTomasiniEFerriPPsicosi e sostanze: problematiche cliniche e assistenziali in un campione di pazienti ricoverati in un reparto psichiatrico per acuti [Psychosis and substances: problems and clinical care in a sample of patients in a psychiatric department for acute care]Psichiatria and Psicoterapia2008271115 Italian

- GoerkeDKumraSSubstance abuse and psychosisChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am201322464365424012078

- AriasFSzermanNVegaPAbuse or dependence on cannabis and other psychiatric disorders. Madrid study on dual pathology prevalenceActas Esp Psiquiatr201341212212923592072

- HambrechtMHäfnerHCannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspectiveAust N Z J Psychiatry200034346847510881971

- MorganCJCurranHVEffects of cannabidiol on schizophrenia-like symptoms in people who use cannabisBr J Psychiatry2008192430630718378995

- ZammitSAllebeckPAndreassonSLundbergILewisGSelf reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort studyBMJ20023257374119912446534

- WinklbaurBEbnerNSachsGThauKFischerGSubstance abuse in patients with schizophreniaDialogues Clin Neurosci200681374316640112

- SuhJJRuffinsSRobinsCEAlbaneseMJKhantzianEJSelf-medication hypothesis: connecting affective experience and drug choicePsychoanal Psychol2008253518532

- LiTLiuXZhaoJAllelic association analysis of the dopamine D2, D3, 5-HT2A, and GABA(A)gamma2 receptors and serotonin transporter genes with heroin abuse in Chinese subjectsAm J Med Genet2002114332933511920858

- PettinatiHMO’BrienCPDundonWDCurrent status of co-occurring mood and substance use disorders: a new therapeutic targetAm J Psychiatry20131701233023223834

- Sánchez-PeñaJFAlvarez-CotoliPRodríguez-SolanoJJPsychiatric disorders associated with alcoholism: 2 year follow-up of treatmentActas Esp Psiquiatr201240312913522723131

- LucchiniABravinSCataldiniRDepressione e Dipendenze Patologiche: L’esperienza dei Servizi Territoriali [Depression and Pathological Addictions: The Experience of the Territorial Services]Milan, ItalyFranco Angeli2004 Italian

- MaremmaniAGRovaiLBacciardiSThe long-term outcomes of heroin dependent-treatment-resistant patients with bipolar 1 comorbidity after admission to enhanced methadone maintenanceJ Affect Disord2013151258258923931828

- SaniGKotzalidisGDVöhringerPEffectiveness of short-term olanzapine in patients with bipolar I disorder, with or without comorbidity with substance use disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol201333223123523422396

- HeffnerJLAnthenelliRMAdlerCMStrakowskiSMBeaversJDelBelloMPPrevalence and correlates of heavy smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents with bipolar and cannabis use disordersPsychiatry Res2013210385786223684537

- GrosDFMilanakMEBradyKTBackSEFrequency and severity of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders in prescription opioid dependenceAm J Addict201322326126523617869

- PacekLRStorrCLMojtabaiRComorbid alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: a national surveyJ Dual Diagn201394

- BradyKTSinhaRCo-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobiological effects of chronic stressAm J Psychiatry200516281483149316055769

- PruessnerJCChampagneFMeaneyMJDagherADopamine release in response to a psychological stress in humans and its relationship to early life maternal care: a positron emission tomography study using [11C]racloprideJ Neurosci200424112825283115028776

- PostRMKalivasPBipolar disorder and substance misuse: pathological and therapeutic implications of their comorbidity and cross-sensitisationBr J Psychiatry2013202317217623457180

- Ministero del Lavoro, della Salute e delle Politiche SocialiLa Classificazione delle Malattie, dei Traumatismi, degli Interventi Chirurgici e delle Procedure Diagnostiche e Terapeutiche: Versione Italiana della ICD-9-CM [International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification, 2007]Rome, ItalyIstituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato2008 Italian

- RushAJJrFirstMBBlackerDHandbook of Psychiatric Measures2nd edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2007

- LuborskyLClinicians’ judgments of mental health: a proposed scaleArch Gen Psychiatry19627640741713931376

- Stata Corp LPStata Statistical Software: Release 12College Station, TXStata Corp LP2011

- Arcos-BurgosMVélezJISolomonBDMuenkeMA common genetic network underlies substance use disorders and disruptive or externalizing disordersHum Genet2012131691792922492058

- ConnorJPGulloMJChanGYoungRMHallWDFeeneyGFPolysubstance use in cannabis users referred for treatment: drug use profiles, psychiatric comorbidity and cannabis-related beliefsFront Psychiatry201347923966956

- SherKJTrullTJSubstance use disorder and personality disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep200241252911814392

- SansoneRASansoneLASubstance use disorders and borderline personality: common bedfellowsInnov Clin Neurosci2011891013