Abstract

Background

Severe and persistent mental illnesses in children and adolescents, such as early- onset schizophrenia spectrum (EOSS) disorders and pediatric bipolar disorder (pedBP), are increasingly recognized. Few treatments have demonstrated efficacy in rigorous clinical trials. Enduring response to current medications appears limited. Recently, olanzapine was approved for the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia or acute manic/mixed episodes in pedBP.

Methods

PubMed searches were conducted for olanzapine combined with pharmacology, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Searches related to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were limited to children and adolescents. The bibliographies of the retrieved articles were hand-checked for additional relevant studies. The epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment of EOSS and pedBP, and olanzapine’s pharmacology are reviewed. Studies of olanzapine treatment in youth with EOSS and pedBP are examined.

Results

Olanzapine is efficacious for EOSS and pedBP. However, olanzapine is not more efficacious than risperidone, molindone, or haloperidol in EOSS and is less efficacious than clozapine in treatment-resistant EOSS. No comparative trials have been done in pedBP. Olanzapine is associated with weight gain, dyslipidemia, and transaminase elevations in youth. Extrapyramidal symptoms, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and blood dyscrasias have also been reported but appear rare.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that olanzapine should be considered a second-line agent in EOSS and pedBP due to its risks for significant weight gain and lipid dysregulation. Awareness of the consistent weight and metabolic changes observed in olanzapine-treated youth focused attention on the potential long-term risks of atypical antipsychotics in youth.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an indication for olanzapine in the treatment of adolescents, 13–17 years old, with schizophrenia or acute manic/mixed episodes in bipolar I disorder (BPI) in December 2009. However, the FDA also formally stated that clinicians may “consider prescribing other drugs first in adolescents” given olanzapine’s increased potential for weight gain and hyperlipidemia in adolescents compared with adults. This article reviews the presentation and treatment of early-onset schizophrenia (EOS) and pediatric bipolar disorder (pedBP), the pharmacology and kinetics of olanzapine, the evidence supporting olanzapine’s efficacy in these two serious mental illnesses among children and adolescents, the safety and tolerability of olanzapine in pediatric patients, and the probable role of olanzapine within the pediatric population compared with the adult population. The information presented in this article was gathered through a systematic PubMed review, with searches conducted for olanzapine combined with pharmacology, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Searches related to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were limited to children and adolescents. The bibliographies of key-retrieved articles were hand-checked for additional relevant studies. Rigorously, controlled data is limited in this population, so observations from nonblinded trials will also be presented. All conclusions are those of the authors and do not reflect specific recommendations of any national organization or government entity.

Early-onset schizophrenia

The incidence of EOS is not well established with epidemiologic studies. However, a number of geographically limited studies focused on hospital admissions have provided consistent estimates of the incidence in children and adolescents. The illness is very uncommon (~0.3/1000) in children younger than 10 years, then increases to approximately 1.3/1000 between ages 10 and 14 years with an even greater increase between 14 and 18 years with incidence rates varying between 2.0 and 5.5/1000. Indeed, at least 5% of those with schizophrenia become ill prior to 14 years of age and up to 20% appear to become ill prior to 18 years of age.Citation1–Citation5 The peak age of onset is between 15 and 20 years in males and between 15 and 25 years in females.Citation6 Modestly more males experience EOS than females (~1.5 males: 1 female).

Diagnostic criteria for EOS are the same as for adult-onset criteria except that psychotic symptoms must be present prior to age 18 years. However, there are some development differences in detailed characteristics of symptoms. Specifically, youth are more likely to have multi-modal hallucinations than adults and frequently personalize their hallucinations giving them names that are frequently stereotyped, such as “Satan,” “my guardian angel,” or the “monster” or derived from visual characteristics, such as the “man with no skin”. They seldom have systematized or bizarre delusional symptoms, though vague paranoia is common. Disorganized thinking is frequently observed.Citation7–Citation10 Younger individuals may have difficulty recognizing their symptoms as abnormal and frequently do not complain spontaneously about hallucinations.Citation11 Youth who will experience EOS frequently show greater premorbid problems with attention, learning, and socialization than individuals who develop schizophrenia as adults. The onset of symptoms in EOS is most often insidious.Citation12,Citation13 Youth with EOS who participate in clinical trials often have more severe psychiatric symptoms, greater neurocognitive deficits, and more pronounced gray matter loss than research participants with adult-onset schizophrenia.Citation14–Citation18 Individuals with EOS are much less likely to have a good outcome than individuals with adult-onset schizophrenia, with the majority having poor or very poor outcomes.Citation13,Citation19–Citation21

Treatment of EOS has traditionally been based on the pharmacologic treatments used for adult-onset schizophrenia. There is little systematic use of psychotherapeutic strategies in this population.Citation22 Efficacy of antipsychotics has been assumed to be generally similar in youth and adults. This view was bolstered by small studies of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), including haloperidol, thioridazine, thiothixene, and loxapine that showed relatively high rates of response.Citation9,Citation23,Citation24 However, considerable sedation was also observed, and there were concerns about extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), which appear to be somewhat more prevalent in youth than adults.Citation25 In the 1990s, a pivotal trial was done showing that youth with treatment-resistant schizophrenia had a robust response to clozapine, the prototypic second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) introduced in 1989.Citation26 However, significant adverse effects were frequent and limited the use of this agent.

As other SGAs have been introduced and approved for use in adults with schizophrenia over the past 20 years (), including olanzapine in 1996, clinicians embraced them hoping both for greater efficacy and fewer adverse effects than the FGAs or clozapine. There was particularly great enthusiasm for olanzapine because its pharmacologic profile was most similar to clozapine’s and it was less prone to EPS than risperidone, which has more potent dopamine D2 antagonism. Enthusiasm for olanzapine was further increased by a study of olanzapine vs haloperidol in 263 patients with first-episode schizophrenia, who were followed for 2 years.Citation27 Although there were no difference in symptom reduction between the two agents in a last observation carried forward analysis, a mixed-model analysis demonstrated an acute advantage for olanzapine in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score, PANSS negative and general symptoms, and a depression rating scale. Results of the 2-year data found that patients treated with olanzapine were significantly more likely to enter remission (olanzapine 57%, haloperidol 44%, P < 0.036) and continued treatment for a longer period of time (olanzapine 322 days, haloperidol 230 days, P < 0.0085) than those treated with haloperidol.Citation28 Perhaps most importantly, the imaging component of this study found that individuals treated with haloperidol experienced significant decreases in brain gray matter volume, whereas neither those treated with olanzapine nor a healthy control group showed any changes.Citation29 Optimism that olanzapine may have particular advantages for treating youth with psychotic symptoms was also heightened with results published from a small pilot study comparing olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of psychotic youth aged 8–20 years.Citation30 This study in the pediatric population found a modest numeric, but not statistically significant, advantage for olanzapine in the response rate (olanzapine 88%, risperidone 74%, haloperidol 53%), premature drop-out (olanzapine 2/16, risperidone 9/19, haloperidol 7/15, P = 0.058), and time to treatment discontinuation (olanzapine 7.4 weeks, risperidone 6.3 weeks, haloperidol 5.7 weeks). However, the same trial also suggested that adverse events with the SGAs may be more common and more severe in youth than in adults. Proponents of olanzapine also focused on results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study in 1,493 adults with chronic schizophrenia. Although there were few clinically significant differences among SGAs and between SGAs and FGAs in the CATIE study, olanzapine had marginally greater benefits as reflected by greater initial reductions in PANSS, greater initial improvements in the Clinical Global Impression (CGI), lower rate of hospitalization due to psychiatric exacerbation, lower discontinuation rates, and longer time to treatment discontinuation.Citation29 As discussed in detail later, the Treatment of Early Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders (TEOSS) study did not identify any advantage for olanzapine compared with risperidone or molindone in children and adolescents with schizophrenia, Citation31 suggesting a potential difference in olanzapine’s efficacy during different stages of schizophrenia.

Table 1 Current FDA indications for second-generation antipsychotics

Pediatric bipolar disorder

Similar to EOSS, there are few epidemiologic studies that rigorously examine the incidence of pedBP. The primary exception to this is a recent small study done in which 3,021 community subjects (14–24 years of age) in Germany were reassessed 10 years later.Citation32 This study found that approximately 1.2% of the youth had experienced a manic or hypomanic episode by 12 years of age and approximately 4.5% had experienced a manic or hypomanic episode by 18 years of age. Manic episodes occurred with similar frequency in males and females, whereas hypomanic episodes were about twice as common in females as males and as mania in either gender. Rates dramatically increased during adolescence. Further, 9% of those with a major depressive episode prior to age 17 years subsequently developed bipolar disorder, which was significantly greater than those with later onset of depression. The incidence of manic and hypomanic episodes in this study is greater than the prevalence of bipolar 1 disorder in adults (4.5% lifetime and 2.8 annual),Citation33 which is typically reported in larger epidemiologic studies, likely due to the expert clinical interviewers used in the German study. In a recent multisite treatment study of 3,658 adults with bipolar disorder, 29% reported onset before age 13 and 67% reported onset by age 18.Citation34 A study of 119 individuals consecutively admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Norway with bipolar disorder found that 13.5% had onset during childhood and 61.6% had onset prior to age 20 and that those who reported an affective temperament had earlier onset.Citation35 The period of peak onset appears to be in 12 and 22 years of age.Citation32 It should be noted that there has been approximately a 40-fold increase in the recognition of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents over the past decade in the US.Citation36

Diagnosis of pedBP has been somewhat contentious with many critics arguing that the disorder is misdiagnosed in a large number of youth. The controversy seems related to two major issues.Citation37 First, in children and many adolescents, the pattern of cycling within a given episode and the duration of episodes appear quite different between youth and adults. Youth frequently have a large number of cycles or mood swings within a single episode of illness. Often, this cycling can occur multiple times a day even though there may be months without an extended euthymic period that would signal the end of the episode. In contrast, most adults demonstrate a fairly consistent mood state throughout any given episode. In pedBP, a single episode will often last for a very extended period giving the appearance of a chronic condition, whereas in adults, episodes are usually limited to a few weeks.Citation38,Citation39 Second, children and, to a lesser extent, adolescents frequently experience mixed states of mania and depression, whereas adults less frequently show such states. The sensitivity and specificity of various individual symptoms of mania and their differential manifestations in other childhood diagnoses are eloquently reviewed by Youngstrom et al.Citation37 Further, there are developmental differences within pedBP, with children frequently showing greater comorbidity with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Childhood-onset bipolar disorder is associated with greater mood lability, irritability, and hallucinations than adolescent-onset bipolar disorder. However, many highly concerning symptoms, including psychotic symptoms, suicidality, grandiosity, and decreased need for sleep, increase during adolescence, often to a greater extent in those with childhood-onset bipolar disorder than those with adolescent-onset bipolar disorder.Citation40 In addition, there is more controversy about the boundaries of the bipolar spectrum in the pediatric population than in the adult population. Criteria for various potential disorders within the spectrum have been most explicitly defined by Leibenluft and colleagues.Citation41 These criteria subdivide bipolar NOS (Not Otherwise Specified) into categories in which a sufficient number of criteria are not met, symptoms do not appear to have sufficient duration, irritability is primary mood state, and moods are severely dysregulated in the context of many symptoms of hyperarousal but in the absence of psychotic symptoms or elation. The latter category, called severe mood dysregulation, appears most common and is likely to be highly heterogeneous.

Most of the current longitudinal studies of pedBP involve limited follow-up and focus primarily on rates of remission and relapse.Citation42–Citation46 However, adults with childhood-onset bipolar disorder appear to experience significantly worse outcomes, including more rapid relapse, less euthymia, and poorer functioning and quality of life than those with adult-onset bipolar disorder.Citation34 In addition, rates of suicidality and suicide attempts are particularly high in adolescents with bipolar disorder (72%–76% and 31%–44%, respectively).Citation47,Citation48 Suicidality in bipolar youth appears to be increased in those with psychotic symptoms.Citation49

Treatment for pedBP has evolved from treatment of adults with bipolar disorder with specific treatment studies for pedBP limited until the past decade. Until 2007, lithium was the only mood-stabilizing agent specifically approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute mania in adolescents. However, this indication does not reflect specific evaluation of the efficacy and safety of lithium in adolescents. Despite this, valproate was probably the most widely used mood stabilizer in the pediatric population until the SGAs were introduced in the 1990s because of its availability in a sprinkle formulation, more favorable therapeutic index (ratio of toxic dose to therapeutic dose), and less onerous side-effect profile compared to lithium. Carbamazepine was also used to some extent. As other antiepileptic drugs, including oxcarbamazepine, gabapentin, topiramate, and lamotrigine, began to be used in adults, they were embraced for use in the pediatric population because they frequently did not require monitoring of blood levels. Lithium was among the first agents specifically studied in youth. Lithium led to greater reductions in the substance use and improvements in the Clinical Global Impressions Scale than placebo in a sample of 25 adolescents with both bipolar disorder and substance abuse.Citation50 A subsequent open trial found that lithium, in conjunction with an antipsychotic in nearly 50% of the cases, led to reduction in acute manic symptoms in approximately two-thirds of adolescents with acute mania and remission in about one-quarter of the participants.Citation51 Further, although no placebo-controlled trials of lithium for mania have been completed in pedBP, one study evaluated the rapid discontinuation of lithium by replacement with placebo or continuation of lithium over 2 weeks in youth who had responded to therapeutic doses of lithium for at least 4 weeks.Citation52 Surprisingly, more than 50% of the participants in both the lithium and the placebo groups experienced significant symptom exacerbation. In addition, among adolescents with both psychotic and manic symptoms, long-term treatment with antipsychotics in addition to lithium was generally required to maintain the initial response to treatment.Citation53

Other open-label studies in pedBP have described significant responses to valproate and carbamazepine, as well as lithium.Citation54,Citation55 However, in many of these trials, the majority of youth were concurrently taking antipsychotics or other mood stabilizers. In the only randomized but open monotherapy trial of mood stabilizers published to date, more than 50% of the participants did not respond to the initially randomized mood stabilizer though 80% of these responded to combined treatment with two mood stabilizers. Citation56 Studies exploring discontinuation of one mood stabilizer after stabilization on combination treatment support are consistent with the requirement of combination therapy for many youth with bipolar disorder.Citation57 Significantly, recent placebo-controlled trials of mood stabilizers published to date have failed to demonstrate efficacy of either oxcarbamazepine or valproate.Citation58,Citation59

Antipsychotics were initially used adjunctively in treatment- resistant bipolar disorder in adults. Clozapine appeared particularly effective. Subsequently, other second- generation agents were studied as a treatment of all phases of bipolar disorder, particularly risperidone and olanzapine. Initially, antipsychotics were used as adjunctive treatment to mood stabilizers and appeared to have increased benefit with no major tolerability issues.Citation60 A blinded, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine adjunctive therapy demonstrated significantly greater reduction in mania scores and greater response rate than valproate monotherapy.Citation61 An open-label trial of olanzapine monotherapy was also very promising.Citation62 Subsequently, a double-blind trial comparing quetiapine with valproate demonstrated superior response and remission rates with quetiapine even though reductions in mean mania scores did not differ.Citation63 Since that time, placebo-controlled trials of each of the atypical antipsychotics other than clozapine – olanzapine,Citation64 aripiprazole,Citation65 risperidone,Citation66 and quetiapineCitation67 – have found that each active agent reduced the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)Citation68 score to a significantly greater extent than placebo over 3 weeks among youth experiencing acute manic/mixed episodes. Based on these results, risperidone and aripiprazole were approved for the acute treatment of mixed and manic episodes of bipolar disorder in youth of 10–17 years old, and olanzapine and quetiapine were approved in adolescents. There has also been one small, double-blind pilot study that failed to show any advantage for quetiapine over placebo in the treatment of depression within pedBP.Citation69 Notably, a large National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-sponsored comparative trial of risperidone, valproate, and lithium has been recently completed and should be reported soon. In summary, there is evidence for significant benefit from antipsychotics in the treatment of mixed and manic states in youth and a lack of efficacy of valproate and oxcarbamazepine. There is no empiric evidence yet of an effective treatment for depression or relapse prevention in youth with bipolar disorder.

Olanzapine pharmacology and pharmacokinetics

Olanzapine is a thienobenzodiazepine analog that binds to a large number of neurotransmitter receptors, including the dopamine D1, D2, and D4 receptors, serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT3 receptors, histamine H1 receptor, muscarinic receptors, α- and β-adrenergic receptors, γ-amino butyrate (GABA)a1 receptor, and the benzodiazepine binding sites.Citation70 Its binding profile is more similar to clozapine’s than any other atypical antipsychotic. Olanzapine’s antipsychotic and mood-stabilizing effects are likely the result of potent antagonism at dopamine and serotonin receptors, with affinity constants ranging from 4 nM to 31 nM. It also binds with high affinity to H1 and M1 receptors. The drug binds with moderate affinity to 5-HT3 and M2–5 receptors and binds weakly to GABA, benzodiazepine binding sites, and β-adrenergic receptors. It is also likely that olanzapine regulates various signaling pathways within the brain, including the extracellular signal-related kinases (ERK1/2), particularly with long-term treatment.Citation71 Developmental differences in the binding profile of olanzapine have not been examined to our knowledge. Olanzapine’s metabolic adverse effects have been hypothesized to relate to its histaminergic binding profile.Citation72,Citation73 In addition, olanzapine-associated weight gain has been linked to genetic variations in the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and β3-adrenergic receptor, leptin, and the G-protein β3 subunit genes.Citation74–Citation76 The anticholinergic side effects are likely related to the muscarinic antagonism and the orthostatic hypotension related to antagonism at α-adrenergic receptors.

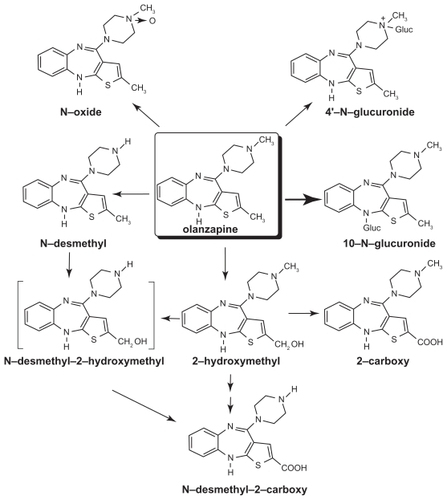

Olanzapine is well absorbed after oral administration and reaches maximal levels in about 5 hours in adults. Eating does not appear to affect olanzapine’s bioavailability. It is excreted in the urine (65%) and feces (35%) over the course of approximately 7 days.Citation77 It is metabolized extensively within the liver undergoing glucuronidation (to yield the primary metabolic products), allylic hydroxylation, oxidation, and dealkylation. Oxidation occurs primarily via the CYP1A2 cytochrome P450 enzyme ().Citation78

Figure 1 Metabolism of olanzapine. The chemical structure and metabolism of olanzapine are shown. Copyright © 1997. Modified with permission from Kassahun K, Mattiuz E, Nyhart E Jr, et al. Disposition and biotransformation of the antipsychotic agent olanzapine in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25(1):81–93.Citation77

Levels are affected by smoking (leading to ~30% reduction in plasma level), gender (women have ~85% increased plasma levels), carbamazepine (decreased plasma levels), and fluvoxamine and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (increased plasma levels).Citation79–Citation84 The elimination half-life ranges from about 27 hours in smokers to 37 hours in nonsmokers. Plasma levels of olanzapine appear to increase slowly over a period of months with a slightly slower time course in women compared with men.Citation81,Citation85 There are no significant differences that appear in bioavailability or half-life of oral tablet and the orally disintegrating form of olanzapine.Citation86

In general, the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine are similar in youth and adults.Citation87,Citation88 Adolescents experience considerable intra-individual variability across time despite stable dosing, which appears somewhat greater in adolescents than adults.Citation85,Citation89 The concentration-to-dose ratio of olanzapine appears generally linear.Citation78 However, adolescents appear to have a higher (~34%) concentration-to-dose ratio than adults even after adjustment for weight.Citation90

Olanzapine efficacy in EOS

The first report of olanzapine treatment in youth with schizophrenia was an open trial done in eight youth with childhood-onset, who had not responded to prior trials with antipsychotics other than clozapine.Citation91 In this study, there was modest improvement in overall symptoms and negative symptoms but no significant change in positive symptoms. A comparison group of 15 treatment-resistant youth exposed to clozapine demonstrated greater benefits only after 6 weeks of treatment. In a trial of 15 children younger than 13 years of age, 10 showed moderate or marked improvements in psychotic symptoms.Citation92 However, all patients who had been previously exposed to antipsychotics did not improve. In contrast, an open-label study of 9 other treatmentresistant children found significant improvements at 12 weeks from baseline in all symptom domains and found that eight of the children sustained improvements over the course of 1 year.Citation93 However, two double-blind studies comparing clozapine and olanzapine in youth with treatment-resistant schizophrenia had similar findings to the initial report.Citation94,Citation95 In each of these trials, clozapine resulted in greater reductions in negative symptoms and, in the most recent trial, greater response rates.

Olanzapine has also been tested in youth with schizophrenia, who are not treatment resistant. The initial open trials for these youth were done in 2003, and included 20 youth (6–15 years old) and 16 adolescents (12–17 years old) respectively.Citation96,Citation97 Both trials showed significant improvements in symptoms, illness severity, and function within 6–8 weeks of initiating treatment. However, improvements in negative symptoms were reported to occur later in the trial that included children and adolescents.Citation97 In the Ross trial, 74% of the youth were considered responders and retained that response status after 1 year of treatment. A similar response rate has been achieved in other open-label trials including a large 6-week trial with an additional 18-week follow-up in 96 adolescents.Citation98,Citation99

Subsequently, olanzapine was openly compared with risperidone and haloperidol in physicians’ choice (nonrandomized) treatment of 43 adolescents with schizophrenia.Citation100 There were no apparent differences in antipsychotic efficacy between the three treatments with significant benefit within 4 weeks of starting treatment. However, haloperidol was associated with greater emergence of depressive symptoms. A more recent trial that involved 16 adolescents with psychotic symptoms treated with olanzapine, 50 treated with risperidone, and 18 treated with quetiapine also failed to detect differences between the antipsychotic efficacy of the agents at 6 months when baseline psychopathology scores were included as a covariate in the analysis.Citation101 However, olanzapine consistently showed the greatest number of reductions in all types of psychotic symptoms. A double-blind, randomized trial of acute psychotic symptoms in 50 youth with either affective or schizophrenic psychoses also failed to show statistically significant differences between treatments.Citation30 In this study, the olanzapine group showed the greatest response rate (88% compared with 74% for risperidone and 53% for haloperidol) and longest duration of treatment. However, the numeric superiority of olanzapine may have partially reflected the preponderance of youth with affective psychoses (69%) in the olanzapine group in contrast with the other two groups where schizophrenic diagnoses were more common. A larger (n = 116), placebo-controlled, randomized trial comparing olanzapine (n = 34) with risperidone (n = 41) and molindone (n = 40) exclusively in youth with EOS, known as the TEOSS trial, again found no statistically significant or numeric differences in symptom reduction between the agents.Citation31,Citation102 However, in contrast to the earlier study, olanzapine treatment was sustained for a numerically shorter period, and numerically fewer participants treated with olanzapine responded than those treated with the other two agents (olanzapine: 34%; risperidone: 46%, molindone: 50%).

One double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine has been done in adolescents 13–17 years old with schizophrenia. Citation103 In this international multisite trial, 72 youth were treated with olanzapine and 35 with placebo. Olanzapine treatment led to much greater and highly statistically significant improvements in the CGI Severity score (P = 0.004), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for Children (BPRS-C)Citation104,Citation105 (P = 0.003), the PANSS total score (P = 0.005), and positive symptom scale (P = 0.002), but not negative symptoms. However, a reviewer at the FDA raised concerns about the study because the positive results of the study were primarily driven by the Russian sites not the US sites.Citation106 Although the BPRS-C symptom reduction seen with olanzapine was similar in both sites (US: −21, Russia: −17), there were dramatic differences in the magnitude of reduction with placebo (US: −15; Russia: −3), resulting in markedly different changes in the P value (US: P = 0.258; Russia: P = 0.003). Importantly, an FDA audit of two Russian sites found no concerns about the conduct of the study. The FDA Director of the Division of Psychiatry Products, Dr. Thomas Laughren, believed that these differences between sites probably reflected differences in the availability of care for youth with schizophrenia between the two countries and greater heterogeneity of the study population at US sites and also believed that olanzapine should be approved in adolescent schizophrenia.

Olanzapine efficacy in pedBP

Olanzapine was initially reported to be useful for treating mania and mixed states in an 8-week, open-label prospective study of 23 youth aged 5–14 years old.Citation62 There was a highly significant improvement in the YMRSCitation107 (−19.0, P < 0.001) and overall response rate (defined as ≥30% reduction in YMRS and CGI-Severity score of mild or less severe) was 61%. Subsequently, DelBello and colleaguesCitation108 examined the effects of olanzapine treatment on brain neurochemistry using proton spectroscopy in 19 adolescents with mania, who were scanned prior to beginning treatment and on days 7 and 28 of treatment. Ten healthy control adolescents were scanned to assess normal variability in brain metabolites over 4 weeks. Ten (58%) of the participants had remission of symptoms. All participants showed increases in ventral prefrontal choline. However, those with remission showed significant increases in medial ventral prefrontal N-acetyl aspartate within 7 days of treatment (P = 0.05) and had increased baseline levels of ventral prefrontal choline compared with nonremitters (P < 0.001). Because N-acetyl aspartate is believed to reflect neuronal vitality, this finding suggests potential beneficial changes in brain structure among some adolescents whose mania is treated with olanzapine. The only randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine for the treatment of manic and mixed states in adolescents (13–17 years old) was conducted by Eli Lilly.Citation64 In that study, 107 youth were treated with olanzapine and 54 with placebo for 3 weeks. The olanzapine group showed significantly greater reduction in the YMRS than the placebo group (olanzapine: −17.7, placebo: −10.0, P < 0.001). Olanzapine also led to dramatically higher response and remission rates than placebo (olanzapine: 48.6% and 35.2%, placebo: 22.2% and 11.1%, P = 0.002 and P = 0.001, respectively). We are unaware of any trials that have compared the efficacy of olanzapine and other mood-stabilizing agents in the pediatric population.

Olanzapine safety and tolerability in youth

Despite the evidence supporting the efficacy of olanzapine in EOS and pedBP, concerns about excessive weight gain with olanzapine emerged early. As olanzapine was used more frequently in youth, additional concerns about metabolic abnormalities, liver function abnormalities, sedation, and prolactin elevations emerged. Subsequently, the safety and tolerability of olanzapine in the pediatric population have been examined in comparison to adults treated with olanzapine. An early postmarketing surveillance study examined the database for olanzapine through March 31, 2000, linked it with patient exposure estimates during the same period provided by Eli Lilly, and divided the analysis into children (birth to 9 years), adolescents (10–19 years), and adults (20 years and older).Citation109 The study found that extrapyramidal syndrome complaint risks were similar across development, and tardive dyskinesia complaint risks were comparable in adolescents and adults. Overrepresented complaints in children included weight gain, liver function abnormalities, sedation and tardive dyskinesia. Overrepresented complaints in adolescents included weight gain, liver function abnormalities, sedation, and prolactin increases. A more recent analysis done by Eli Lilly compared the weight and metabolic data from 454 adolescents aged 13–17 years old exposed to olanzapine (primarily under open conditions) for as long as 32 weeks to the pooled weight data from 7,847 adults treated with olanzapine for up to 32 weeks and pooled metabolic data from adults from four trials.Citation107 The adolescents experienced more frequent and severe weight gain than the adults (>7% weight gain in 65.1% of adolescents and 35.6% of adults, P < 0.001; mean weight gain 7.4 kg in adolescents and 3.2 kg in adults, P < 0.001). Adolescents were also much more likely to develop hyperprolactinemia (adolescents: 55.5%, adults: 29.0%, P < 0.001). However, in contrast, adults had more adverse metabolic changes than the adolescents with 11.8% of adults and 3% of adolescents moving from normal or impaired glucose to high glucose (P < 0.001), and 31%–38% of adults compared with 17%–21% of adolescents developed borderline dyslipidemias (P < 0.001 for all). This likely reflects other lifestyle and metabolic problems including lower insulin reserves in the adults.

The largest and most definitive data review of olanzapine’s safety and tolerability in adolescents, pools all six Eli Lilly-sponsored trials of olanzapine in a total of 179 youth studied under placebo-controlled conditions for up to 6 weeks and 454 youth exposed to olanzapine (primarily under open conditions) for as long as 32 weeks.Citation110 There have also been some trials that compared adverse effects observed in youth treated with olanzapine or other antipsychotics, including data between 45 and 52 weeks of exposure.Citation30,Citation31,Citation93,Citation101,Citation102,Citation111–Citation115 We will examine each of the main adverse effects observed with olanzapine separately.

Weight gain

In the Eli Lilly placebo-controlled adolescent database, youth gained 3.9 kg when treated with olanzapine compared with 0.2 kg when treated with placebo (P < 0.001). In the adolescent-exposure database, the overall weight gain was 7.4 kg, with nearly two-thirds gaining more than 7% of their baseline weight and a 13.3 percentile increase in body mass index (BMI), which is a more appropriate measure of increased size in youth. Overall, 4% of adolescents withdrew from treatment because of weight gain. In examining the time course of weight gain, there appears a marked reduction in the slope of weight gain after 4 weeks of treatment.Citation110 Similar findings of rapid weight gain followed by slower weight gain have been observed in other trials.Citation96,Citation102,Citation111,Citation114

In the comparative studies, olanzapine consistently demonstrated the greatest weight gain both acutely and with more extended use as summarized in . In almost all cases, it has led to significantly more weight gain than other antipsychotics with a very high level of significance. Further, in contrast with the adult literature, studies that directly compare clozapine and olanzapine treatment in youth have found that clozapine increases weight to a lesser or equivalent extent than olanzapine does.Citation95,Citation113,Citation114 One study examining 65 youth treated with olanzapine, clozapine, or risperidone found elevations in parents’ and patients’ pretreatment BMIs. Female gender and younger age when treated were associated with the magnitude of antipsychotic-associated weight gain independent of medication. Further, individuals with low pretreatment BMIs initially show more rapid weight gain than their heavier peers even though total weight gain with treatment is less.Citation116

Table 2 Reported weight and metabolic changes with pediatric olanzapine treatment

Glucose metabolism

In the Eli Lilly placebo-controlled database, olanzapine-treated youth showed a 3.6 mg/dL (0.2 mmol/L) increase in fasting glucose, whereas placebo-treated youth showed a similarly sized decrease. Although not clinically significant, this finding was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001). Further, 3% of adolescents in the exposure database moved from normal or borderline glucose levels into the diabetic range.Citation110 Increases in fasting glucose with olanzapine treatment ranging from 0.6 to 10 mg/dL have been reported in several other pediatric trials ().Citation30,Citation31,Citation95 A study of 45 antipsychotic- naïve youth treated with olanzapine found significant increases in glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance (measured with homeostasis model assessment–insulin resistance [HOMA-IR]) with P values between 0.02 and 0.03.Citation115 There have also been multiple case reports of youth developing diabetes during olanzapine treatment.Citation117–Citation120 It is clear that youth are less likely to rapidly develop diabetes as a consequence of olanzapine treatment than adults because most teens have large insulin reserves. It is not yet clear to what extent these increases in glucose persist with sustained treatment.

Lipid metabolism

In the Eli Lilly database, youth treated with olanzapine showed increases in total cholesterol and triglycerides relative to their peers treated with placebo [cholesterol 11.7 mg/dL (0.03 mmol/L) compared to no change and triglycerides 26.7 mg/dL (0.03 mmol/L) compared to a decrease of 8.9 mg/dL (−0.1 mmol/L); P = 0.002 and P = 0.007, respectively]. Those in the exposure database showed identical changes. Approximately one-fifth of the patients developed borderline elevations in total cholesterol (>200 and <240 mg/dL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL cholesterol >130 and <160 mg/dL), and triglycerides (>150 and <200 mg/dL), and 17.8% developed hypertriglyceridemia.Citation110 Interestingly, changes in lipid levels were slightly less in the study of antipsychotic-naïve youth ranging from 11.5 mg/dL for LDL cholesterol to 24.3 mg/dL for triglycerides with all P values less than 0.004.Citation115 Similar changes have been reported in other small studies that included individuals previously exposed to antipsychotics ().Citation30,Citation31,Citation95 Again there is limited information about the long-term course of these lipid changes.

Liver dysfunction

The Eli Lilly databases also report significant elevations in liver enzymes associated with olanzapine treatment. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) increased by 20.0 and 21.4 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increased by 6.4 U/L and 8.2 U/L, and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) increased by 7.5 and 9.0 U/L in the placebo-controlled and exposure databases, respectively (P ≤ 0.002 for each comparison). In contrast, total bilirubin decreased significantly (−1.7 and −1.1 μmol/L) in the two databases. Similar increases in ALT and AST have been reported in other pediatric studies of olanzapine.Citation30,Citation31 In the TEOSS trial, such elevations were more common in youth treated with olanzapine than those treated with either risperidone or molindone. In this study, there also appeared to be a tendency for these increases to diminish somewhat with continuing treatment.Citation102 Eight (1.8%) of the 454 participants in the Lilly adolescent exposure database discontinued treatment due to liver function problems. These elevations may reflect nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease), although imaging studies and long-term follow-up is not yet available. In a retrospective chart review of youth treated with olanzapine alone, divalproex alone, or the combination of olanzapine and divalproex, 59% of those treated with olanzapine alone had at least 1 elevated hepatic enzyme over an average of 8 months of treatment while only 26% of those treated with divalproex alone did. However, all of those treated with the combination experienced at least 1 elevation and 42% of these had persistent elevations throughout the treatment period. One of the youth treated with both agents developed clinically significant steatohepatitis that resolved when the olanzapine was stopped.Citation121

Hyperprolactinemia

In adults, olanzapine has not been associated with significant increases in prolactin. However, children and adolescents appear very sensitive to the prolactin-increasing effects of all antipsychotics, including olanzapine.Citation122 The Eli Lilly placebo databases report acute prolactin increases of 11.4 μg/L with olanzapine compared with a slight decrease with placebo (P < 0.001). In the longer-term exposure database, the increase is much more significant at 23.0 μg/L compared with a decrease of −4.2 μg/L in the pooled adult data (P = 0.004). Interestingly, fewer female adolescents experienced prolactin elevations than male adolescents. Similar changes have been described in other clinical trials.Citation30,Citation31 Further, Wudarsky reported that 7 of 10 youth treated with olanzapine had elevations above the upper limits of normal for their age and gender. However, prolactin elevations with risperidone have consistently been found to be more extreme than with olanzapine in pediatric patients.Citation30,Citation31 It appears that olanzapine plasma concentration is significantly correlated with serum prolactin levels.Citation123 However, most clinical trials do not report high rates of prolactin-related adverse events, such as menstrual irregularities, gynecomastia, or galactorrhea. The large Eli Lilly exposure database identified such problems in only 0.6%–4.2% of participants. The long-term consequences of moderate elevations in prolactin during adolescence are unknown.

Sedation

Most pediatric trials of olanzapine report high rates of sedation ranging from about 40% to 91%.Citation30,Citation31,Citation95,Citation96,Citation100 In the Eli Lilly databases, the incidence appears somewhat lower (17.4%–19.0%). However, if the reported rates of somnolence are generally additive to those of sedation, the rates move into the 40% range reported in other studies. Unfortunately, sedation often does not resolve in individuals who continue long-term treatment.Citation100,Citation102 Sedation can have significant impact upon a youth’s ability to participate in school and other age-appropriate activities. Less than 1% of youth in Eli Lilly’s databases discontinued participation due to sedation.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

Almost all types of extrapyramidal adverse effects, including parkinsonian symptoms, dystonia, dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), have been reported in youth treated with olanzapine. However, these adverse events appear to occur much less often with olanzapine than with other antipsychotics including aripiprazole in youth. The incidence in the Lilly exposure database was 2.3% for parkinsonian symptoms, 5.5% for akathisia, and 1.4% for dyskinetic movements. Generally, those symptoms that do occur are minimal to mild. In comparative studies, olanzapine is consistently associated with fewer and less-severe extrapyramidal adverse events than risperidone, haloperidol, or molindone.Citation30,Citation31,Citation100 There is 1 case report of persistent dystonic movements emerging during olanzapine treatment and persisting up to 6 weeks after switching to clozapine treatment.Citation124 However, very few children and adolescents have been maintained for an extended period on a single antipsychotic or followed for sufficiently long periods to rigorously assess the medication-specific incidence of this late appearing and persistent adverse effect.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

NMS is a rare, potentially fatal, and idiosyncratic drug reaction that often occurs early in the course of antipsychotic treatment. NMS previously has been associated with the use of classical high-potency neuroleptics.Citation125,Citation126 Case reports suggest that NMS resulting from treatment with olanzapine and other SGAs has a more insidious course than NMS precipitated by first-generation high-potency agents. In addition, temperature elevations may emerge late in the course. Cognitive symptoms including agitation and delirium may be more prominent. However, there have been two case reports of classic NMS occurring during olanzapine monotherapy,Citation127,Citation128 one with olanzapine overdose,Citation129 and several in the context of polypharmacy with other psychotropics (as described in two recent reviews).Citation126,Citation130

Hematologic effects

Although clozapine is best known for its risk of hematologic abnormalities, there are many case reports of neutropenia being caused by other antipsychotics as well. Olanzapine and ziprasidone seem to be more likely than the other newer antipsychotics to cause such abnormalities. Citation131 There are some case reports where olanzapine was the only medication being taken.Citation132 Consequently, the FDA required a label change noting the risk of neutropenia and leukopenia with olanzapine treatment in August 2009. The label notes that this risk appears to be heightened in individuals with a history of blood dyscrasias or low white blood cell counts, particularly those induced by other drugs or those on drugs that have similar effects. In such cases, the patient’s blood count should be monitored frequently when treatment is initiated and treatment should be interrupted if the absolute neutrophil count drops below 1000 cells/cm3. It is unknown whether the risk for neutropenia is greater in the pediatric population than in the adult population.

Overdose

In adult studies, Lily data of over 3,100 subjects showed that the largest ingestion was 300 mg and that person did well with supportive care. However, there are multiple other reports of fatalities that some believe are related to olanzapine. Citation133–Citation135 There have been at least two fatalities in children who have overdosed on olanzapine.Citation136 Often, individuals with olanzapine overdoses develop EPS or NMS, respiratory symptoms, and mental status changes.Citation129,Citation137–Citation139 Overdoses in pediatric patients are reviewed by Theisen.Citation140 Management is primarily supportive and symptoms may take several days to a few weeks to fully resolve.

Olanzapine use in the pediatric population

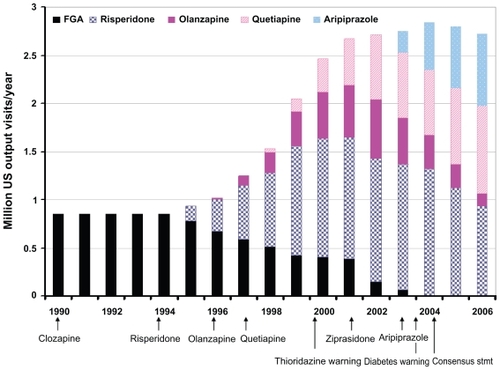

The pattern of olanzapine’s use over time in the US pediatric population relative to other antipsychotics is shown in . When olanzapine was approved by the FDA in 1996, it almost immediately began being used in the pediatric population.Citation140–Citation149 However, its use never became as prevalent as risperidone’s. Quetiapine’s use was of similar magnitude by 2001. However, as data about olanzapine-associated weight gain emerged, the FDA issued requirements that SGA labels warn about the weight and metabolic risks; the American Diabetes Association and the American Psychiatric Association released a consensus statement indicating that olanzapine and clozapine had the greatest risk for such side effects and olanzapine use in the pediatric population quickly diminished to 5% or less of the total antipsychotics prescribed.Citation146,Citation148

Figure 2 Patterns of antipsychotic use in the pediatric population of the United States. Following the introduction of each second-generation antipsychotic except clozapine, there has been rapid use within the pediatric population. However, risperidone, the first agent introduced after clozapine, has consistently been used more widely than the other agents. Further, safety considerations appear to have limited use of clozapine, ziprasidone, and earlier in 2003, olanzapine. This figure is a synthesis of data from multiple sources.Citation135–Citation140,Citation142 Number of prescriptions and proportion related to each agent are approximate.

Evidence from the CATIE trial that showed a slight advantage of olanzapine over other first-line antipsychotics in total duration of treatment and symptom response and from a first-episode study showing neuroimaging benefits compared with haloperidol, as well as the similarities between the binding profiles of olanzapine and clozapine, led some clinicians to use olanzapine in a few youth with very severe or persistent psychotic symptoms.Citation27,Citation29,Citation150 Youth with bipolar disorder are even less likely to be treated with olanzapine. In a recent study of pediatric bipolar treatment, it was used less often than any other antipsychotic (including FGAs).Citation151

Olanzapine appears to be used more frequently in some parts of Europe but still to a lesser extent than either risperidone or quetiapine. In the CAFEPS longitudinal naturalistic study of youth with positive psychotic symptoms about 15% were treated with olanzapine.Citation101 In Canada, use is also somewhat greater than in the United States with about 6000 children (~22% of those who are treated with antipsychotics) receiving prescriptions for olanzapine annually between 2003 and 2006.Citation147 In countries outside the United States, aripiprazole appears to be less frequently used, so olanzapine and quetiapine are likely to be viewed as the antipsychotics with the least risk for EPS.

Conclusions

Olanzapine has clear efficacy for pedBP and EOSS. However, it also appears to have very great potential for promoting weight gain, increased insulin secretion, and dyslipidemia in children and adolescents. These adverse risks appear to be remarkably increased relative to other antipsychotics with the possible exception of clozapine. In the light of this extreme risk and because there is no compelling evidence that olanzapine has greater antipsychotic efficacy than other agents in either unselected youth with EOSS and other psychotic illnesses or in treatment-resistant EOSS, we argue that olanzapine should not be considered a first-line treatment for EOSS. Because there is clear evidence that clozapine has superior efficacy to olanzapine in treatment-resistant EOSS, we feel clinicians and families should seriously consider a trial of clozapine rather than olanzapine in such youth. There are no comparative studies examining the mood-stabilizing or antimanic properties of olanzapine relative to other SGAs. In the absence of any empiric data regarding comparative efficacy, olanzapine’s heightened risks for weight gain and metabolic dysregulation suggest to the authors that it should not be considered a first-line treatment for pedBP either. However, because there is no treatment of choice for youth with pedBP, who have failed to respond to multiple first-line treatments, olanzapine might have a role in treating such children and adolescents.

Although olanzapine is unlikely to be used frequently in the pediatric population, it remains an alternative for some individuals. Such individuals might include those who are underweight, have no family history of diabetes or dyslipidemia, or are particularly sensitive to the extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics with more potent dopamine D2 receptor binding. These conclusions are supported by the FDA’s recent decision to approve olanzapine for the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia or manic/mixed states in bipolar disorder, provided clinicians and families carefully consider prescribing other agents first due to olanzapine’s marked risks for significant weight gain and lipid dysregulation in adolescents.

Olanzapine has played a critical role in alerting scientists and the public to the metabolic consequences of most antipsychotics, particularly within children and adolescents. The consistent weight and metabolic changes observed in olanzapine-treated youth spurred investigations of such effects among youth treated with other antipsychotics and provided a strong impetus for long-term studies of antipsychotic tolerability in youth.

Disclosures

Dr Maloney has received software for a computer intervention in schizophrenia from Posit Science. Dr Sikich receives research funding from NIMH, NIH, Foundation of Hope, Case Western Reserve University (subcontract from NICHD), NY Institute for Mental Hygiene Research (subcontract from NIMH), and Bristol Myers-Squibb. She is participating or has participated in clinical trials with Otsuka, Bristol Myers- Squibb, Neuropharm, Curemark, and Seaside Pharmaceuticals. She also received medication for clinical trials from Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Bristol Myers-Squibb, and software for a computer intervention in schizophrenia from Posit Science. She has served as a consultant for Sanofi Aventis within the past 2 years. She has given CME talks that have been indirectly supported by Bristol Myers-Squibb.

References

- HafnerHNowotnyBEpidemiology of early-onset schizophreniaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci199524580927654792

- MaziadeMGingrasNRodrigueCLong-term stability of diagnosis and symptom dimensions in a systematic sample of patients with onset of schizophrenia in childhood and early adolescence. I: nosology, sex and age of onsetBr J Psychiatry199616933613708879724

- ThomsenPHSchizophrenia with childhood and adolescent onset – a nationwide register-based studyActa Psychiatr Scand19969431871938891086

- SchimmelmannBGConusPCottonSMcGorryPDLambertMPretreatment, baseline, and outcome differences between early-onset and adult-onset psychosis in an epidemiological cohort of 636 first-episode patientsSchizophr Res200795131817628441

- LuomaSHakkoHOllinenTJarvelinMRLindemanSAssociation between age at onset and clinical features of schizophrenia: the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort studyEur Psychiatry200823533133518455370

- HafnerHRiecherAMaurerKLofflerWMunk-JorgensenPStromgrenEHow does gender influence age at first hospitalization for schizophrenia? A transnational case register studyPsychol Med19891949039182594886

- RemschmidtHESchulzEMartinMWarnkeATrottGEChildhood-onset schizophrenia: history of the concept and recent studiesSchizophr Bull19942047277457701279

- RussellATThe clinical presentation of childhood-onset schizophreniaSchizophr Bull19942046316467701273

- SpencerEKCampbellMChildren with schizophrenia: diagnosis, phenomenology, and pharmacotherapySchizophr Bull19942047137257701278

- WerryJSMcClellanJMAndrewsLKHamMClinical features and outcome of child and adolescent schizophreniaSchizophr Bull19942046196307701272

- SchaefferJLRossRGChildhood-onset schizophrenia: premorbid and prodromal diagnostic and treatment historiesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241553854512014786

- EggersCBunkDThe long-term course of childhood-onset schizophrenia: a 42-year followupSchizophr Bull1997231051179050117

- RopckeBEggersCEarly-onset schizophrenia: a 15-year follow-upEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200514634135016220219

- BassoMRNasrallahHAOlsonSCBornsteinRACognitive deficits distinguish patients with adolescent- and adult- onset schizophreniaNeuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol19971021071129150511

- GieddJNJeffriesNOBlumenthalJChildhood-onset schizophrenia: progressive brain changes during adolescenceBiol Psychiatry199946789289810509172

- Tuulio-HenrikssonAPartonenTSuvisaariJHaukkaJLonnqvistJAge at onset and cognitive functioning in schizophreniaBr J Psychiatry200418521521915339825

- BiswasPMalhotraSMalhotraAGuptaNComparative study of neuropsychological correlates in schizophrenia with onset in childhood, adolescence and adulthoodEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200615636036616604435

- FrazierJAMcClellanJFindlingRLTreatment of early- onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS): demographic and clinical characteristicsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200746897998817667477

- JarbinHOttYVon KnorringALAdult outcome of social function in adolescent-onset schizophrenia and affective psychosisJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200342217618312544177

- FleischhakerCSchulzETepperKMartinMHennighausenKRemschmidtHLong-term course of adolescent schizophreniaSchizophr Bull200531376978016123530

- RemschmidtHMartinMFleischhakerCForty-two-years later: the outcome of childhood-onset schizophreniaJ Neural Transm2007114450551216897595

- SikichLFindlingRSchluzSIndividual and school-based interventionsSchizophrenia in Adolescents and Children: Assessment, Neurobiology and TreatmentBaltimore (MD)John Hopkins University Press2005257287

- PoolDBloomWMielkeDHRonigerJJJrGallantDMA controlled evaluation of loxitane in seventy-five adolescent schizophrenic patientsCurr Ther Res Clin Exp197619199104812671

- RealmutoGMEricksonWDYellinAMHopwoodJHGreenbergLMClinical comparison of thiothixene and thioridazine in schizophrenic adolescentsAm J Psychiatry19841414404426367494

- KeepersGAClappisonVJCaseyDEInitial anticholinergic prophylaxis for neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal syndromesArch Gen Psychiatry19834010111311176138011

- KumraSFrazierJAJacobsenLKChildhood-onset schizophrenia. A double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparisonArch Gen Psychiatry19965312109010978956674

- LiebermanJATollefsonGTohenMComparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidolAm J Psychiatry200316081396140412900300

- GreenAILiebermanJAHamerRMOlanzapine and haloperidol in first episode psychosis: two-year dataSchizophr Res2006861323424316842972

- LiebermanJAStroupTSMcEvoyJPEffectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophreniaN Engl J Med2005353121209122316172203

- SikichLHamerRMBashfordRASheitmanBBLiebermanJAA pilot study of risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol in psychotic youth: a double-blind, randomized, 8-week trialNeuropsychopharmacology200429113314514583740

- SikichLFrazierJAMcClellanJDouble-blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) studyAm J Psychiatry2008165111420143118794207

- BeesdoKHoflerMLeibenluftELiebRBauerMPfennigAMood episodes and mood disorders: patterns of incidence and conversion in the first three decades of lifeBipolar Disord200911663764919689506

- MerikangasKRAkiskalHSAngstJLifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replicationArch Gen Psychiatry200764554355217485606

- PerlisRHDennehyEBMiklowitzDJRetrospective age at onset of bipolar disorder and outcome during two-year follow-up: results from the STEP-BD studyBipolar Disord200911439140019500092

- OedegaardKJSyrstadVEMorkenGAkiskalHSFasmerOBA study of age at onset and affective temperaments in a Norwegian sample of patients with mood disordersJ Affect Disord20091181322923319246102

- MorenoCLajeGBlancoCJiangHSchmidtABOlfsonMNational trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youthArch Gen Psychiatry20076491032103917768268

- YoungstromEABirmaherBFindlingRLPediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosisBipolar Disord2008101 Pt 219421418199237

- GellerBTillmanRBolhofnerKProposed definitions of bipolar I disorder episodes and daily rapid cycling phenomena in preschoolers, school-aged children, adolescents, and adultsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717221722217489716

- TillmanRGellerBDefinitions of rapid, ultrarapid, and ultradian cycling and of episode duration in pediatric and adult bipolar disorders: a proposal to distinguish episodes from cyclesJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200313326727114642014

- BirmaherBAxelsonDStroberMComparison of manic and depressive symptoms between children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disordersBipolar Disord2009111526219133966

- LeibenluftECharneyDSTowbinKEBhangooRKPineDSDefining clinical phenotypes of juvenile maniaAm J Psychiatry2003160343043712611821

- GellerBTillmanRCraneyJLBolhofnerKFour-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotypeArch Gen Psychiatry200461545946715123490

- BirmaherBAxelsonDCourse and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a review of the existing literatureDev Psychopathol20061841023103517064427

- RendeRBirmaherBAxelsonDPsychotic symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder and family history of psychiatric illnessJ Affect Disord2006961212713116844230

- StroberMBirmaherBRyanNPediatric bipolar disease: current and future perspectives for study of its long-term course and treatmentBipolar Disord20068431132116879132

- DelBelloMPHansemanDAdlerCMFleckDEStrakowskiSMTwelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episodeAm J Psychiatry2007164458259017403971

- LewinsohnPSeeleyJKleinDGellerBDelBelloMPBipolar disorder in adolescents: epidemiology and suicidal behaviorBipolar Disorder in Childhood and Early AdolescenceNew YorkGuilford2003724

- AxelsonDBirmaherBStroberMPhenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disordersArch Gen Psychiatry200663101139114817015816

- CaetanoSCOlveraRLHunterKAssociation of psychosis with suicidality in pediatric bipolar I, II and bipolar NOS patientsJ Affect Disord2006911333716445989

- GellerBCooperTBSunKDouble-blind and placebocontrolled study of lithium for adolescent bipolar disorders with secondary substance dependencyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19983721711789473913

- KafantarisVColettiDJDickerRPadulaGKaneJMLithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a large open trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20034291038104512960703

- KafantarisVColettiDJDickerRPadulaGPleakRRAlvirJMLithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a placebo-controlled discontinuation studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443898499315266193

- KafantarisVColettiDJDickerRPadulaGKaneJMAdjunctive antipsychotic treatment of adolescents with bipolar psychosisJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140121448145611765291

- WagnerKDWellerEBCarlsonGAAn open-label trial of divalproex in children and adolescents with bipolar disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241101224123012364844

- PavuluriMNHenryDBCarbrayJANaylorMWJanicakPGDivalproex sodium for pediatric mixed mania: a 6-month prospective trialBipolar Disord20057326627315898964

- KowatchRASuppesTCarmodyTJEffect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039671372010846305

- FindlingRLMcNamaraNKGraciousBLCombination lithium and divalproex sodium in pediatric bipolarityJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200342889590112874490

- WagnerKDKowatchRAEmslieGJA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescentsAm J Psychiatry200616371179118616816222

- WagnerKDReddenLKowatchRAA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex extended-release in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescentsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200948551953219325497

- PavuluriMNHenryDBCarbrayJASampsonGNaylorMWJanicakPGOpen-label prospective trial of risperidone in combination with lithium or divalproex sodium in pediatric maniaJ Affect Disord200482Suppl 1S10311115571784

- DelbelloMPSchwiersMLRosenbergHLStrakowskiSMA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent maniaJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241101216122312364843

- FrazierJABiedermanJTohenMA prospective open-label treatment trial of olanzapine monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200111323925011642474

- BarzmanDHDelBelloMPAdlerCMStanfordKEStrakowskiSMThe efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine versus divalproex for the treatment of impulsivity and reactive aggression in adolescents with co-occurring bipolar disorder and disruptive behavior disorder(s)J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200616666567017201610

- TohenMKryzhanovskayaLCarlsonGOlanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of adolescents with bipolar maniaAm J Psychiatry2007164101547155617898346

- FindlingRLNyilasMForbesRAAcute treatment of pediatric bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, with aripiprazole: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry200970101441145119906348

- HaasMDelbelloMPPandinaGRisperidone for the treatment of acute mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyBipolar Disord200911768770019839994

- FDA_website fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess?DevelopmentResources/UCM163241.pdf. Published 2007Accessed Sep 15, 2009

- YoungRCBiggsJTZieglerVEMeyerDAA rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivityBr J Psychiatry1978133429435728692

- DelBelloMPChangKWelgeJAA double-blind, placebocontrolled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorderBipolar Disord200911548349319624387

- BymasterFPCalligaroDOFalconeJFRadioreceptor binding profile of the atypical antipsychotic olanzapineNeuropsychopharmacology199614287968822531

- FumagalliFFrascaASpartaMDragoFRacagniGRivaMALongterm exposure to the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine differently upregulates extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 phosphorylation in subcellular compartments of rat prefrontal cortexMol Pharmacol20066941366137216391238

- WirshingDAWirshingWCKysarLNovel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilitiesJ Clin Psychiatry199960635836310401912

- KroezeWKHufeisenSJPopadakBAH1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugsNeuropsychopharmacology200328351952612629531

- TemplemanLAReynoldsGPArranzBSanLPolymorphisms of the 5-HT2C receptor and leptin genes are associated with antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain in Caucasian subjects with a first-episode psychosisPharmacogenet Genomics200515419520015864111

- UjikeHNomuraAMoritaYMultiple genetic factors in olanzapine- induced weight gain in schizophrenia patients: a cohort studyJ Clin Psychiatry20086991416142219193342

- GunesAMelkerssonKIScordoMGDahlMLAssociation between HTR2C and HTR2A polymorphisms and metabolic abnormalities in patients treated with olanzapine or clozapineJ Clin Psychopharmacol2009291656819142110

- KassahunKMattiuzENyhartEJrDisposition and biotransformation of the antipsychotic agent olanzapine in humansDrug Metab Dispos199725181939010634

- KandoJCShepskiJCSatterleeWPatelJKReamsSGGreenAIOlanzapine: a new antipsychotic agent with efficacy in the management of schizophreniaAnn Pharmacother19973111132513349391688

- LucasRAGilfillanDJBergstromRFA pharmacokinetic interaction between carbamazepine and olanzapine: observations on possible mechanismEur J Clin Pharmacol19985486396439860152

- CallaghanJTBergstromRFPtakLRBeasleyCMOlanzapine. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profileClin Pharmacokinet199937317719310511917

- KellyDLConleyRRTammingaCADifferential olanzapine plasma concentrations by sex in a fixed-dose studySchizophr Res199940210110410593449

- HiemkeCPeledAJabarinMFluvoxamine augmentation of olanzapine in chronic schizophrenia: pharmacokinetic interactions and clinical effectsJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222550250612352274

- KroonLADrug interactions with smokingAm J Health Syst Pharm200764181917192117823102

- SpinaEde LeonJMetabolic drug interactions with newer antipsychotics: a comparative reviewBasic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol2007100142217214606

- DarbyJKPastaDJWilsonMGHerbertJLong-term therapeutic drug monitoring of risperidone and olanzapine identifies altered steady-state pharmacokinetics: a clinical, two-group, naturalistic studyClin Drug Investig2008289553564

- MarkowitzJSDeVaneCLMalcolmRJPharmacokinetics of olanzapine after single-dose oral administration of standard tablet versus normal and sublingual administration of an orally disintegrating tablet in normal volunteersJ Clin Pharmacol200646216417116432268

- GrotheDRCalisKAJacobsenLOlanzapine pharmacokinetics in pediatric and adolescent inpatients with childhood-onset schizophreniaJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020222022510770461

- TheisenFMHaberhausenMSchulzESerum levels of olanzapine and its N-desmethyl and 2-hydroxymethyl metabolites in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: effects of dose, diagnosis, age, sex, smoking, and comedicationTher Drug Monit200628675075917164690

- BachmannCJHaberhausenMHeinzel-GutenbrunnerMRemschmidtHTheisenFMLarge intraindividual variability of olanzapine serum concentrations in adolescent patientsTher Drug Monit200830110811218223472

- AichhornWMarksteinerJWalchTAge and gender effects on olanzapine and risperidone plasma concentrations in children and adolescentsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717566567417979586

- KumraSJacobsenLKLenaneMChildhood-onset schizophrenia: an open-label study of olanzapine in adolescentsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19983743773859549958

- SholevarEHBaronDAHardieTLTreatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia with olanzapineJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2000102697810933117

- MozesTGreenbergYSpivakBTyanoSWeizmanAMesterROlanzapine treatment in chronic drug-resistant childhood-onset schizophrenia: an open-label studyJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200313331131714642019

- ShawPSpornAGogtayNChildhood-onset schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized clozapine-olanzapine comparisonArch Gen Psychiatry200663772173016818861

- KumraSKranzlerHGerbino-RosenGClozapine and “high-dose” olanzapine in refractory early-onset schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized and double-blind comparisonBiol Psychiatry200863552452917651705

- FindlingRLMcNamaraNKYoungstromEABranickyLADemeterCASchulzSCA prospective, open-label trial of olanzapine in adolescents with schizophreniaJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200342217017512544176

- RossRGNovinsDFarleyGKAdlerLEA 1-year open-label trial of olanzapine in school-age children with schizophreniaJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200313330130914642018

- QuintanaHWilsonMS2ndPurnellWLaymanAKMercanteDAn open-label study of olanzapine in children and adolescents with schizophreniaJ Psychiatr Pract2007132869617414684

- DittmannRWMeyerEFreislederFJEffectiveness and tolerability of olanzapine in the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders: results from a large, prospective, open-label studyJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2008181546918294089

- GothelfDApterAReidmanJOlanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment of adolescent patients with schizophreniaJ Neural Transm2003110554556012721815

- Castro-FornielesJParelladaMSoutulloCAAntipsychotic treatment in child and adolescent first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal naturalistic approachJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200818432733618759642

- FindlingRJohnsonJMcClellanJDouble-blind maintenance safety and effectiveness findings from the Treatment of Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Study (TEOSS)J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201049658359420494268

- KryzhanovskayaLSchulzSCMcDougleCOlanzapine versus placebo in adolescents with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2009481607019057413

- OverallJEPfefferbaumBThe Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for ChildrenPsychopharmacol Bull19821821016 1978; 133:429–4357111598

- HughesCWRintelmannJEmslieGJLopezMMacCabeNA revised anchored version of the BPRS-C for childhood psychiatric disordersJ Child Adolesc PsychopharmacolSpring20011117793

- LaughrenTMemorandum on recommendation for approvable actions for Zyprexa Pediatric Supplements for bipolar disorder (acute mania) and schizophrenia. [pdf from website]4292007 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApproval-Process/DevelopmentResources/UCM163360.pdf. Published 2010Accessed Feb 10, 2010

- YoungRCBiggsJTZieglerVEMeyerDAA rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivityBr J Psychiatry1978133429435728692

- DelBelloMPCecilKMAdlerCMDanielsJPStrakowskiSMNeurochemical effects of olanzapine in first-hospitalization manic adolescents: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studyNeuropsychopharmacology20063161264127316292323

- WoodsSWMartinASpectorSGMcGlashanTHEffects of development on olanzapine-associated adverse eventsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241121439144612447030

- KryzhanovskayaLARobertson-PlouchCKXuWCarlsonJLMeridaKMDittmannRWThe safety of olanzapine in adolescents with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trialsJ Clin Psychiatry200970224725819210948

- RatzoniGGothelfDBrand-GothelfAWeight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241333734311886029

- MozesTEbertTMichalSESpivakBWeizmanAAn open-label randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of childhood-onset schizophreniaJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200616439340316958565

- FleischhakerCHeiserPHennighausenKWeight gain associated with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone in children and adolescentsJ Neural Transm2007114227328017109073

- FleischhakerCHeiserPHennighausenKWeight gain in children and adolescents during 45 weeks treatment with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidoneJ Neural Transm2008115111599160818779922

- CorrellCUManuPOlshanskiyVNapolitanoBKaneJMMalhotraAKCardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescentsJAMA2009302161765177319861668

- GebhardtSHaberhausenMHeinzel-GutenbrunnerMAntipsychotic-induced body weight gain: predictors and a systematic categorization of the long-term weight courseJ Psychiatr Res200943662062619110264

- DomonSEWebberJCHyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia secondary to olanzapineJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200111328528811642478

- SelvaKAScottSMDiabetic ketoacidosis associated with olanzapine in an adolescent patientJ Pediatr2001138693693811391346

- BlochYVardiOMendlovicSLevkovitzYGothelfDRatzoniGHyperglycemia from olanzapine treatment in adolescentsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol20031319710212804130

- CourvoisieHECookeDWRiddleMAOlanzapine-induced diabetes in a seven-year-old boyJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200414461261615662154

- Gonzalez-HeydrichJRachesDWilensTELeichtnerAMezzacappaERetrospective study of hepatic enzyme elevations in children treated with olanzapine, divalproex, and their combinationJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200342101227123314560173

- WudarskyMNicolsonRHamburgerSDElevated prolactin in pediatric patients on typical and atypical antipsychoticsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol19999423924510630453

- AlfaroCLWudarskyMNicolsonRCorrelation of antipsychotic and prolactin concentrations in children and adolescents acutely treated with haloperidol, clozapine, or olanzapineJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2002122839112188977

- KumraSJacobsenLKLenaneMCase series: spectrum of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders and extrapyramidal side effects in childhood-onset schizophreniaJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19983722212279473920

- PicardLSLindsaySStrawnJRKaneriaRMPatelNCKeckPEJrAtypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome: diagnostic controversies and considerationsPharmacotherapy200828453053518363536

- NeuhutRLindenmayerJPSilvaRNeuroleptic malignant syndrome in children and adolescents on atypical antipsychotic medication: a reviewJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200919441542219702493

- Abu-KishkIToledanoMReisADanielDBerkovitchMNeuroleptic malignant syndrome in a child treated with an atypical antipsychoticJ Toxicol Clin Toxicol200442692192515533033

- MendhekarDNDuggalHSPersistent amnesia as a sequel of olanzapine- induced neuroleptic malignant syndromeJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200618455255317135384

- CohenLGFataloAThompsonBTDi Centes BergeronGFloodJGPoupoloPROlanzapine overdose with serum concentrationsAnn Emerg Med199934227527810424935

- CroarkinPEEmslieGJMayesTLNeuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotics in pediatric patients: a review of published casesJ Clin Psychiatry20086971157116518572981

- DelieuJMHorobinRWDuguidJKExploring the relationship of drug-induced neutrophil immaturity and haematological toxicity to drug chemistry using quantitative structure-activity modelsMed Chem20095171419149645

- StubnerSGrohmannREngelRBlood dyscrasias induced by psychotropic drugsPharmacopsychiatry200437Suppl 1S707815052517

- ElianAAFatal overdose of olanzepineForensic Sci Int19989132312359530833

- GerberJECawthonBOverdose and death with olanzapine: two case reportsAm J Forensic Med Pathol200021324925110990286

- ChuePSingerPA review of olanzapine-associated toxicity and fatality in overdoseJ Psychiatry Neurosci200328425326112921220

- AntiaSXSholevarEHBaronDAOverdoses and ingestions of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescentsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200515697098516379518

- ChambersRACaracansiAWeissGOlanzapine overdose cause of acute extrapyramidal symptomsAm J Psychiatry199815511163016319812139

- CatalanoGCooperDSCatalanoMCButeraASOlanzapine overdose in an 18-month-old childJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol19999426727110630456

- KochharSNwokikeJNJankowitzBSholevarEHAbedTBaronDAOlanzapine overdose: a pediatric case reportJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200212435135312625996

- TheisenFMGrabarkiewiczJFegbeutelCHubnerAMehler-WexCRemschmidtHOlanzapine overdose in children and adolescents: two case reports and a review of the literatureJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200515698699516379519