Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to investigate the role that psychopathological dimensions as overt aggression and impulsivity play in determining suicide risk in benign chronic pain patients (CPPs). Furthermore we investigated the possible protective/risk factors which promote these negative feelings, analyzing the relationship between CPPs and their caregivers.

Methods

We enrolled a total of 208 patients, divided into CPPs and controls affected by internistic diseases. Assessment included collection of sociodemographic and health care data, pain characteristics, administration of visual analog scale (VAS), Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11 (BIS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), and a caregiver self-administered questionnaire. All variables were statistically analyzed.

Results

A significant difference of VAS, MOAS-total/verbal/auto-aggression, HDRS-total/suicide mean scores between the groups were found. BIS mean score was higher in CPPs misusing analgesics. In CPPs a correlation between MOAS-total/verbal/auto-aggression with BIS mean score, MOAS with HDRS-suicide mean score and BIS with HDRS-suicide mean scores were found. The MOAS and BIS mean scores were significantly higher when caregivers were not supportive.

Conclusion

In CPPs, aggression and impulsivity could increase the risk of suicide. Moreover, impulsivity, overt aggression and pain could be interrelated by a common biological core. Our study supports the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the CPPs management and the necessity to supervise caregivers, which may become risk/protective factors for the development of feelings interfering with the treatment and rehabilitation of CPPs.

Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain describes pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with a present or potential tissue damage, or described as such”.Citation1 It is one of the leading reasons for which patients seek medical care (Lorenz et al).Citation2 Pain represents a signal of danger to body integrity, however, it cannot only be explained in terms of anatomical circuits and sensors, thus it is necessary to consider its multidimensional characteristics. Several factors such as personality, intellectual, emotional and psychological characteristics, past experiences and relations with others, all contribute to the qualitative and quantitative definition of pain. The nerve and the biochemical pathways activated by pain sensations create complex responses which involve the limbic, endocrine, and immune system pathways. According to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definitionCitation1 chronic pain is a continuous or recurrent pain that persists beyond the expected normal time of healing. Chronic pain is commonly categorized as malignant and non-malignant: the first substantially indicates cancer pain while the second could refer to various diseases such as headache, neuralgia, and the deafferentation syndrome (phantom limb). Being almost considered “incurable”, chronic pain has become a major epidemiological issue and an actual social problem in both pediatric and adult patients. The prevalence of chronic pain among the general population ranges from 10%–80%, depending upon the population being studied, survey method and definition in use.Citation3,Citation4

Chronic pain has a strong negative emotional impact on patients and their quality of life, due to goal frustration, external attribution for negative outcomes and perceived injustice, leading to unfavorable behavioral consequences that can directly contribute to its maintenance.Citation5,Citation6 It is well-known that the co-occurrence of pain and depression is common. The prevalence of depression among chronic pain patients (CPPs) has been estimated between 1.5%–100% depending upon the different study settings.Citation7 Scientific literature often underlines the bi-directional interpretation of the co-occurrence of pain and depression: depression accompanying pain could be either the “cause” or the “result” and pain itself could be considered as a reactive depression.Citation8,Citation9

Chronic pain has also been correlated with symptoms of impulsivity, anger, and aggressionCitation10–Citation14 that could in turn be related to different factors, such as the increase of muscle reactivity in the painful area, increased adipose tissue, endogenous opioid system dysfunction, as well as the genetic polymorphisms affecting the opioid, serotonergic, and adrenergic systems.Citation15,Citation16

Moreover, prior research has identified a link between pain and suicide. The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in these patients has been estimated to be between 5% and 14% and that of suicide ideation about 20%.Citation17 The degree to which an individual can tolerate negative emotions may play an important role in the decision to attempt suicide. CPPs frequently go through suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions as a direct consequence of the depressed mood.Citation18,Citation19

The primary aim of this study was to assess the emotional dimensions in CPPs, different by depressed mood, categorized as overt aggression and impulsivity. The secondary aim was to evaluate the suicide risk in relation to the presence of overt aggression and impulsivity and to demonstrate how these emotional aspects were affected by the relationship between CPPs and their caregivers.

Subjects and methods

In this study we analyzed 208 adult patients, aged between 18 and 88 years, who were referred to the University Hospital of Bari. Participants were divided into two groups: CPPs and control group. The CPPs consisted of 99 patients with a diagnosis of benign chronic pain who were enrolled at the Pain Management ambulatory of the Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit. The control group consisted of 109 patients who did not suffer from chronic pain, but who were affected by gastrointestinal diseases, hypertension, diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This group was enrolled at the Internal and Public Medicine ambulatory of the Internal and Specialistic Medicine Department and consisted of unwell subjects because we wanted to prove that a generic disease status could not cause the onset of aggressive and impulsive components. However, the heterogeneous diseases of these patients did not allow us to assess whether there is a correlation between each disease and the emotional aspects associated with it. All participants were consecutively examined in the period between September 2009 and March 2010. For all enrolled patients exclusion criteria included the presence of specific psychiatric disorders that could influence the aggression and/or impulsivity indices, such as mental retardation, dementia, and psychosis. For CPPs, inclusion criteria consisted of the presence of pain for more than 6 months prior to the visit. Exclusion criteria included the presence of a terminal illness, cancer or other malignancies and the inability to comprehend or to give informed consent. The Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico Di Bari approved this study. In addition, all the study procedure details were explained to the CPPs and the control group and a written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment. For both groups, we collected sociodemographic data and health care variables consisting of age, sex, marital status, educational level, work activity, being a parent or not, living alone or not, and finally the presence of any psychiatric diagnosis. Causes, localization, quality, intensity, duration of pain, and any intake of analgesic drugs were also recorded. Moreover, participants were also asked to complete a structured self-administered questionnaire, specifically developed by the research group, to detect the perceived support given by their caregiver, in terms of physical help, listening to him/her, the amount of health care given, and the availability of assistance. We did not administer the questionnaire to the control group as they did not require caregivers.

Assessment

For both groups, a team of psychiatrists evaluated patients in two sessions: the first, for the collection of sociodemographic and clinical data and the second for the application of the following standardized instruments.

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)Citation20

The VAS is a visual representation of the amplitude of pain that a patient is believed to feel at a specific time. This scale is a 10 cm horizontal line with no numbers, marks, or descriptive vocabulary words along the length of the line. The VAS theoretically ranges between 0 and 10, where 0 indicates no pain and 10 corresponds to the worst pain imaginable. It is self-administered and the patient is asked to draw a sign on the line that represents the level of the pain experienced within the last 4 weeks prior to that moment.

Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS)Citation21

The MOAS is a reliable 25-item clinician-administered scale, which provides a weekly assessment of the aggressiveness. The MOAS starts from a behavioral checklist and arrives at an estimation system, all in five points, which represent increasing levels of severity. It also includes important forms of aggression, such as attempted suicide and intimidation. The score reflects the individual’s most severe aggressive acts during the past week. The MOAS is divided into four domains: 1) verbal aggression, 2) aggression toward objects, 3) auto-aggression, and 4) physical aggression. The score in each domain is multiplied by a factor assigned to that category: 1 for verbal aggression, 2 for aggression toward objects, 3 for auto-aggression, and 4 for physical aggression. Thus, the total MOAS score ranges from 0 (no aggression) to 40 (maximum grade of aggression). The psychometric properties of the MOAS were validated in Italy by assessing its inter-rater reliability (P>0.90) and predictive power.Citation22

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11 (BIS)Citation23

A 30-item self-report scale, the BIS measures impulsivity in terms of answers like “never/rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, and “almost always/always.” The total score is the result of three sub-scales (motor, attentional, and non-planning) and ranges from 30 to 120. The Italian validated version of BIS was used.Citation24

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)Citation25

The HDRS is an 18-item physician-administered scale that rates the presence and the severity of depressive symptoms. The third item of the HDRS concerns the level of a patient’s current suicidal thoughts. A total score of between 10 and 15 is indicative of possible depression, between 16 and 25 of mild depression, between 26 and 28 of moderate depression, and more than 28 of severe depression. The HDRS test was administered as the full version. However, we have extrapolated the data of item 3 because this item could give information regarding a “tendency” toward suicide risk.

Caregiver self-administered questionnaire

The caregiver self-administered questionnaire comprises a 7-item self-report questionnaire measuring the patient’s perception of caregiver in terms of answers like “never”, “sometimes”, and “often”. The items are as follows: caregiver supports the patient, caregiver ignores the patient, caregiver takes care of the patient, caregiver asks how to help the patient, caregiver listens to the patient, caregiver expresses irritation with the patient, caregiver gets distracted by talking to the patient.

Statistical analysis

All the variables considered were statistically analyzed. Univariate analysis for sociodemographics and social health context variables was performed using the chi-square test. If necessary, the Fisher’s exact test was used. For the measurement of the outcome variables such as VAS, MOAS, MOAS auto-aggression, MOAS verbal aggression, MOAS aggression toward objects, MOAS physical aggression, BIS, HDRS, and HDRS suicide, the independent Student’s t-test was used. For each outcome of statistically significant difference between CPPs and controls, we used a logistic regression model. Spearman’s coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was used to analyze the correlation between the MOAS, BIS, and HDRS total and suicide risk scores. The significance level was set at P<0.05 for the differences between the groups. Data were analyzed using STATA software 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for Mac OS.

Results

Sociodemographic, health care variables, and pain features

Sociodemographic and health care data of both the CPPs and control group are shown in . The two groups did not statistically differ in average age or marital status, living alone, having at least one child, or minimum work activity; male patients predominated in the CPPs, whereas, having an educational qualification (upper secondary school diploma/degree) was more frequent in the control group, both with a statistically significant difference; the psychiatric diagnosis, represented by anxiety and mood disorders, was more frequent in CPPs than controls, with a statistically significant difference.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and health care variables of CPPs and control group

Causes, localization, and duration of pain, as well as analgesic intake in CPPs are shown in . The analgesic drugs used were first level medications, such as paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Over-intake was defined as the consumption of an analgesic at a higher dose/frequency compared to what was established in the technical sheet of the drug or to what was prescribed by the physician.

Table 2 Causes, localization, duration of pain, and analgesic intake of CPPs

VAS

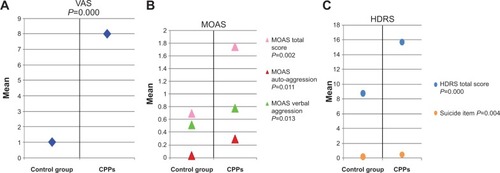

A statistically significant difference (t=27.75, P=0.000) of VAS mean values between CPPs (8±2) and control group (1±1.6) was found. This difference was confirmed by the logistic regression model (odds ratio [OR] =2.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] =1.9–3.1, P=0.000). The results of this scale are shown in .

Figure 1 Statistical differences.

Abbreviations: VAS, Visual Analog Scale; CPPs, Chronic Pain Patients; MOAS, Modified Overt Aggression Scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

MOAS

A statistically significant difference (t=3.07, P=0.002) of MOAS total mean score between CPPs (1.7±3.3) and control group (0.7±1.2) was found. Considering the mean scores of each subscale, a statistically significant difference was found for auto-aggression and verbal aggression; on the other hand, it was not found for physical aggression and aggression toward objects. After the regression model was performed, a significant difference between CPPs and controls was found only for auto-aggression (OR =5, 95% CI =1.4–17.6, P=0.043). P-value results are shown in .

BIS

No statistically significant difference (t=−1.98, P=0.05) of BIS total mean score between CPPs (59.5±10.2) and controls (62.65±12.1) was found. Despite that, among the CPPs, BIS total mean score was higher among subjects who “often” misused analgesics (69.1±10.1) compared to subjects who “sometimes” (64.4±8.6) or “never” misused them (61.2±9.4, P=0.32).

HDRS

A statistically significant difference (t=5.73, P=0.000) of HDRS total mean score between CPPs (15.7±8.9) and controls (8.7±8.5) was found; this difference was confirmed by the logistic regression analysis (OR =1.1, 95% CI =1.04–1.12; P=0.000). In particular, a statistically significant difference (t=2.92, P=0.004) between CPPs (0.5±0.8) and controls (0.2±0.4) occurred for the suicide item mean value; it was also confirmed by the logistic regression model (OR =2.3, 95% CI =1.3–3.9, P=0.006). These results are shown in .

Considering only the CPPs group, a significant, although small correlation between the MOAS total score, the MOAS auto-aggression score, and the MOAS verbal aggression score with the BIS total score was found. Although, in the control group, these correlations were not present. In both the CPPs and control group, no correlation was found between the MOAS aggression toward objects score, the MOAS physical aggression score, and the BIS total score.

Considering only the CPPs group again, a significant correlation between the MOAS total score, the MOAS auto-aggression score, the MOAS verbal aggression score, the MOAS aggression toward objects score, the MOAS physical aggression score, and the HDRS suicide score was found. In the control group such correlation was only present for the total MOAS score, the MOAS auto-aggression, and the MOAS verbal aggression scores with the HDRS suicide score.

As for the correlation between the BIS scores and the HDRS suicide scores, in the CPPs group the BIS total score was statistically correlated with the HDRS suicide score, whereas in the control group no correlation was present (Spearman’s rho =0.081, P=0.403). Significant correlations in the CPPs and control group are shown in .

Table 3 Significant correlations in CPPs and control group

Caregiver self-administered questionnaire

Considering the results of the caregiver self-administered questionnaire, in the item “caregiver ignores patient” mean values of the variables of the MOAS total score, MOAS aggression toward objects score, and MOAS physical aggression score were statistically significant for the “never/often” compared to the “sometimes” category.

In the item “caregiver listens to patient” mean values of the variable MOAS physical aggression were statistically significant for the “never/sometimes” category compared to the “often” category.

In the item “caregiver distracts patient” mean, total MOAS and BIS scores were statistically significant for the “never/sometimes” category compared to the “often” category.

These results are summarized in .

Table 4 Structured self-administered questionnaire about caregivers’ results

Discussion

Chronic pain leads to suffering, overwhelming disability, and personal impairment, pervading all aspects of social and emotional life. It has to be considered as not only a symptom, but a real syndrome that requires a multidimensional approach. From this point of view, it appears very important to investigate the emotional aspects associated with the chronic pain experience.

Several studies have actually researched the depression and anxiety manifestations in chronic pain sufferers,Citation17,Citation26,Citation27 while little attention has been given to other emotional and behavioral states. By reference to this background, the aim of our study was to evaluate factors associated with chronic pain, such as overt aggression and impulsivity.

In literature, the relationship between chronic pain and aggressiveness was indirectly assessed by studying the connection with anger,Citation10,Citation28 in fact, aggression is a behavioral reaction developing from feelings of anger. Fishbain et alCitation13 analyzed the prevalence of different forms of anger in community non-patients, community patients, patients with acute pain, and CPPs. The authors found that anger was more frequent in CPPs compared to the other groups, supporting the clinical perception that many CPPs are angry. In our study, we found that overt aggression, in particular verbal and auto-aggression, was more frequent in the CPPs compared to the control group.

Few studies have analyzed the relationship between chronic pain and impulsivity. Marino et alCitation14 suggested that, although impulsivity was not a prominent trait in CPPs, there was a potential relationship between impulsivity and risk for opioid analgesic misuse in chronic lower-back pain patients. Similar results were revealed in our study, in fact we found no significant difference in impulsivity between CPPs and the control group, but at the same time, we highlighted an inappropriate use of analgesics in 33% of CPPs, giving strength to the hypothesis that analgesic misuse could be an indirect consequence of impulsivity in these patients.

Comparing MOAS and BIS scores, we found a correlation between impulsivity and overt aggression in CPPs; in particular patients who had high scores in BIS (score >63.8) were more likely to have higher scores in the MOAS verbal and the MOAS auto-aggression categories. It was assumed that potential genetic contributors to the pain related effects of anger, may be warranted by genetic polymorphisms affecting the serotonergic and adrenergic systems.Citation15,Citation16 On the other hand, an altered metabolism of serotonin, noradrenergic, and dopaminergic activities could play an important role in impulsive behaviours.Citation29,Citation30 These results suggest that impulsivity, overt aggression, and pain could be interrelated by a common biological–structural core, that involves different factors including serotonergic and adrenergic systems, although, future studies are needed to extend these findings and to examine the potential biological mechanisms (impaired function of the endogenous opioid system, immune system, neurotransmitters, and metabolism) which could explain the relationship between chronic pain and behavioral and emotional states associated to it.

Several studies revealed depressive symptoms and suicide risk in CPPs.Citation19,Citation31–Citation34 In our study, the HDRS showed a higher total score and a higher suicide-item score in the CPPs compared to the control group, thus confirming literature results.

Impulsivity and aggression are moreover strongly linked to suicidality in several epidemiological, clinical, retrospective, prospective, and family studies.Citation33,Citation35

It is reasonable to argue that several psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and mood disorders, could elevate risk for suicide. In our study, we found a statistically significant difference of HDRS suicide item, between patients with and without psychiatric comorbidity in both CPPs and control group (CPPs P=0.007, control group P=0.002). However, CPPs showed higher levels of overt aggression compared to the control group, which could be considered an additive factor to suicide risk in these patients.

In CPPs, when MOAS and HDRS suicide scores were compared, we found a correlation between scores of all forms of overt aggression (auto-aggression, verbal aggression, aggression toward objects, physical aggression) and HDRS suicide scores, while in the control group a correlation was revealed only between MOAS auto-aggression scores, MOAS verbal aggression scores, and HDRS suicide scores. When comparing BIS and HDRS suicide scores, we found a correlation in CPPs. Higher levels of aggression and impulsivity could increase suicide risk, which could be interpreted as an act which cannot be simply attributable to severe depression.

Taking the caregiver self-administered questionnaire into account, the average MOAS, MOAS auto-aggression, MOAS verbal aggression, MOAS aggression toward objects, MOAS physical aggression, and BIS scores were significantly higher when the caregiver was not being supportive to the CPPs. These findings suggest that the quality of family support and the responsible caregiver’s assistance, could be a protective factor in reducing aggression and impulsivity, although, it is important to consider that the patient’s anger/aggression could have a negative impact on the positive/supportive relationships of the caregivers and treatment staff. For these reasons, it is important to establish content and scope of a training program for caregivers and the CPPs’ families, for the control of the pain associated symptoms. We must admit that our analysis about the caregiver’s support has been limited by the use of a non-validated questionnaire, although, it was designed for the specific purposes of this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings have some potential implications. Chronic pain diseases, which cause more distress than other types of illnesses, should be considered as “syndromes” that require appropriate multidisciplinary interventions. Significantly improved results of pain and pain-related measures were shown after intervention in the form of interdisciplinary assessment and a rehabilitation program.Citation36 Moreover, it is important that caregivers take care of pain patients, because they may become risk or protective factors for the development of negative feelings that could interfere with the treatment and rehabilitation of CPPs.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Task Force on Taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of PainClassification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms2nd edSeattleIASP Press1994

- LorenzKASherbourneCDShugarmanLRHow reliable is pain as the fifth vital sign?J Am Board Fam Med200922329129819429735

- YeoSNState-of-the-art pain management in SingaporeSingapore Med Association News2007392426

- Abu-Saad HuijerHChronic pain: a reviewJ Med Liban2010581212720358856

- de AlmeidaJGBragaPELotufo NetoFPimentaCAChronic pain and quality of life in schizophrenic patientsRev Bras Psiquiatr2013351132023567595

- MooreRADerrySTaylorRSStraubeSPhillipsCJThe Costs and Consequences of Adequately Managed Chronic Non Cancer Pain and Chronic Neuropathic PainPain Practice2014141799423464879

- BairMJRobinsonRLKatonWKroenkeKDepression and pain comorbidity: a literature reviewArch Intern Med2003163202433244514609780

- CaillietRPain: mechanisms and managementPhiladelphiaFA Davis Company1993

- MagniGMoreschiCRigatti-LuchiniSMerskeyHProspective study on the relationship between depressive symptoms and chronic musculoskeletal painPain19945632892978022622

- BrunsDDisorbioJMHanksRChronic nonmalignant pain and violent behaviorCurr Pain Headache Rep20037212713212628054

- GreenwoodKAThurstonRRumbleMWatersSJKeefeFJAnger and persistent pain: current status and future directionsPain20031031–21512749952

- NielKAHunnicutt-FergusonKReidyDEMartinezMAZeichnerARelationship of pain tolerance with human aggressionPsychol Rev20071011141144

- FishbainDALewisJEBrunsDDisorbioJMGaoJMeyerLJExploration of anger constructs in acute and chronic pain patients vs community patientsPain Pract201111324025120738789

- MarinoENRosenKDGutierrezAEckmannMRamamurthySPotterJSImpulsivity but not sensation seeking is associated with opioid analgesic misuse risk in patients with chronic painAddict Behav20133852154215723454878

- BruehlSChungOYBurnsJWAnger expression and pain: an overview of findings and possible mechanismsJ Behav Med200629659360616807797

- BruehlSBurnsJWChungOYChontMPain-related effects of trait anger expression: neural substrates and the role of endogenous opioid mechanismsNeurosci Biobehav Rev200933347549119146872

- TsangAVon KorffMLeeSCommon chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disordersJ Pain200891088389118602869

- EdwardsRRSmithMTKudelIHaythornthwaiteJPain-related catastrophizing as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in chronic painPain20061261–327227916926068

- FishbainDABrunsDMeyerLJLewisJEGaoJDisorbioJMExploration of the relationship between disability perception, preference for death over disability, and suicidality in patients with acute and chronic painPain Med201213455256122487542

- FlynnDvan SchaikPvan WerschAA comparison of multi-item Likert and visual analogue scales for the assessment of transactionally defined coping functionEur J Psychol Assess2004204958

- KaySRWolkenfelfFMurrillLMProfiles of aggression among psychiatric patients: I. nature and prevalenceJ Nerv Ment Dis199817695395463418327

- MargariFMatarazzoRCasacchiaMItalian validation of MOAS and NOSIE: a useful package for psychiatric assessment and monitoring of aggressive behavioursInt J Methods Psychiatr Res200514210911816175880

- PattonJHStanfordMSBarrattESFactor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness ScaleJ Clin Psychol19955167687748778124

- FossatiADi CeglieAAcquariniEBarrattESPsychometric properties of an Italian version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11) in nonclinical subjectsJ Clin Psychol200157681582811344467

- HamiltonMDevelopment of a rating scale for primary depressive illnessBr J Soc Clin Psychol1967642782966080235

- GerritsMMVogelzangsNvan OppenPvan MarwijkHWvan der HorstHPenninxBWImpact of pain on the course of depressive and anxiety disordersPain2012153242943622154919

- KazemiHGhassemiSFereshtehnejadSMAminiAKolivandPHDoroudiTAnxiety and depression in patients with amputated limbs suffering from phantom pain: a comparative study with non-phantom chronic painInt J Met Psychiat Res201342218225

- TaftCSchwartzSLiebschutzJMIntimate partner aggression perpetration in primary care chronic pain patientsViolence Vict201225564966121061870

- VirkkunenMNuutilaAGoodwinFKLinnoilaMCerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels in male arsonistsArch Gen Psychiatry19894432412472435256

- KreekMJNielsenDAButelmanERLaForgeKSGenetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addictionNat Neurosci20058111450145716251987

- BradenJBSullivanMDSuicidal thoughts and behavior among adults with self-reported pain conditions in the national comorbidity survey replicationJ Pain20089121106111519038772

- IlgenMAKleinbergFIgnacioRVNoncancer Pain Conditions and Risk of SuicideJAMA Psychiatry201370769269723699975

- Baca-GarciaEDiaz-SastreCGarcía ResaESuicide attempts and impulsivityEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2005255215215615549343

- ShuchangHMingweiHHongxiaoJEmotional and neurobehavioural status in chronic pain patientsPain Res Manag2011161414321369540

- WyderMDe LeoDBehind impulsive suicide attempts: indications from a community studyJ Affect Disord20071041–316717317397934

- Pietilä HolmnerEFahlströmMNordströmAThe effects of interdisciplinary team assessment and a rehabilitation program for patients with chronic painAm J Phys Med Rehabil2013921778323255272