Abstract

Background

With the advent of the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) has been subsumed into the obsessive-compulsive disorders and related disorders (OCDRD) category.

Objective

We aimed to determine the empirical evidence regarding the potential relationship between BDD and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) based on the prevalence data, etiopathogenic pathways, and clinical characterization of patients with both disorders.

Method

A comprehensive search of databases (PubMed and PsycINFO) was performed. Published manuscripts between 1985 and May 2015 were identified. Overall, 53 studies fulfilled inclusion criteria.

Results

Lifetime comorbidity rates of BDD–OCD are almost three times higher in samples with a primary diagnosis of BDD than those with primary OCD (27.5% vs 10.4%). However, other mental disorders, such as social phobia or major mood depression, are more likely among both types of psychiatric samples. Empirical evidence regarding the etiopathogenic pathways for BDD–OCD comorbidity is still inconclusive, whether concerning common shared features or one disorder as a risk factor for the other. Specifically, current findings concerning third variables show more divergences than similarities when comparing both disorders. Preliminary data on the clinical characterization of the patients with BDD and OCD indicate that the deleterious clinical impact of BDD in OCD patients is greater than vice versa.

Conclusion

Despite the recent inclusion of BDD within the OCDRD, data from comparative studies between BDD and OCD need further evidence for supporting this nosological approach. To better define this issue, comparative studies between BDD, OCD, and social phobia should be carried out.

Introduction

With the advent of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) has been subsumed into the category of obsessive-compulsive disorders and related disorders (OCDRD) along with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), hoarding disorder, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder. Based on this conceptualization, BDD shares epidemiological, etiopathogenic, psychopathological, functional, evolutionary, and treatment-related features with OCD to a greater extent compared with empirical evidence from anxiety disorders or somatoform disorders.Citation1 This assumption has been discussed over the last 20 years, resulting in an abundance of research from independent (BDD or OCD vs controls) and comparative studies (BDD vs OCD vs controls) so far.

Given this, several theoretical reviews have been previously carried out on this issue.Citation2–Citation5 Nonetheless, there are no theoretical reviews that include the latest findings on the comorbidity of BDD and OCD, neither epidemiological data, explanatory theories nor clinical characteristics. In addition, the previous reviews made inferences based on remarkable methodological divergences among the manuscripts gathered (eg, independent vs comparative studies). For this reason, we considered the need to carry out an up-to-date theoretical review with a more accurate methodological approach that would provide us with a better understanding of the potential relationship between OCD and BDD. Specifically, we sought to display main findings on three major issues, namely: 1) What is the prevalence of comorbidity between BDD and OCD? 2) Are there any etiopathogenic pathways that may account for the comorbidity between BDD and OCD? 3) What are the clinical characteristics of patients with comorbid OCD and BDD?

Method

Search strategy

A literature search was carried out in June 2015 through PsycINFO, Scopus, and PubMed databases from 1985 to May 2015. Terms employed included indexing terms (eg, MeSH) and free texts: ([body dysmorphic disorder OR BDD OR dysmorphophobia] AND [obsessive-compulsive disorder OR OCD] AND [comorbidity]).

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria included studies in which: 1) some individuals were diagnosed with BDD and others with OCD or 2) some individuals were diagnosed with both disorders and were compared with others with one of these disorders alone. Psychiatric diagnosis should have been made according to DSM-III-R (1987) or DSM-IV (1994). Studies solely enrolling patients either with BDD or with OCD were excluded because they did not allow us to perform direct comparison between both disorders.

Study selection

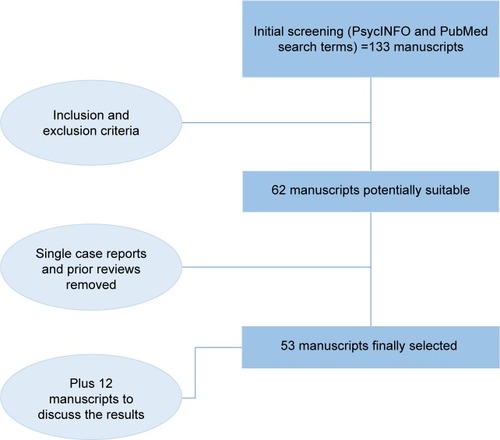

Initial screening using search terms yielded 133 manuscripts (). After reviewing all manuscripts, the authors agreed that 62 manuscripts available in English language could fulfill inclusion criteria and were potentially suitable for this review. Of them, four manuscripts were removed because they were not original findings (theoretical reviews) and five manuscripts were also ruled out because they were case reports with limited evidence, most of them comprising single case studies. Finally, 53 manuscripts fulfilled inclusion criteria and comprised this theoretical review. We added 12 related manuscripts to help with the discussion of the evidence.

Data extraction

Findings from each manuscript were distributed throughout the text, according to the following setup: 1) prevalence data; 2) etiopathogenic pathways; and 3) characteristics of patients with comorbid OCD and BDD. From a methodological approach, we also recorded for each manuscript: 1) sample size; 2) assessment instruments; 3) influence of confounding variables; 4) comparison group employed; and 5) outcome measures.

Results

Prevalence of the comorbidity between OCD and BDD

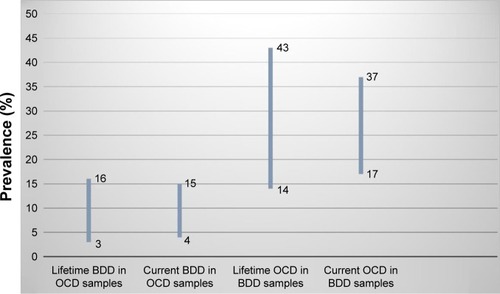

The first goal of this review was to evaluate if patients with either OCD or BDD were likely to have the other diagnosis. For this purpose, we divided this paragraph into two sections: findings from samples with a primary diagnosis of OCD and those from samples with a primary diagnosis of BDD. Moreover, for each section, the results displayed were taken into account if they reflected lifetime or current comorbidity rates. Overall findings are illustrated in .

Prevalence of BDD in patients with a primary diagnosis of OCD

Studies on the prevalence of BDD in individuals with a primary diagnosis of OCD have mostly enrolled adult outpatient samples from western OCD specialty centers. Concerning this issue, the lifetime prevalence of BDD within these samples ranged from 3% to 16% (mean =10.4%).Citation6–Citation15 Specifically, data from the largest samples (N=901, N=457, N=442, and N=382) yielded prevalence data from 8.7% to 15%, relative to 3% in non-OCD patients.Citation7,Citation8,Citation12,Citation14 Conversely, the only study conducted in an Asian country (Indian sample, N=231) consisting of both children and adults evidenced that 3% of them had comorbidity with BDD.Citation9 The lower comparative prevalence could be the result of cross-cultural differences in BDD prevalence, although there is still no epidemiological data on the prevalence of primary BDD within Indian samples. Notwithstanding, a recent multicentric international study (N=457) found significant differences in comorbidity rates between subsamples (countries) with the highest prevalence evidenced in the Canadian OCD patients (up to 78% also met criteria for BDD, although statistical power was low because of the sample size).Citation11 Regarding the current prevalence of BDD among OCD samples, studies are more limited and found that this type of comorbidity occurred in 3.8%–15.3% of OCD patients (mean =9%) relative to 0% in non-OCD controls.Citation16–Citation18 Particularly, data from the study with the highest percentage should be taken with caution as: 1) BDD diagnosis was merely determined using a self-report screening instrument (Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire) and 2) the OCD sample was recruited from an inpatient psychiatric setting.Citation18 Overall, neither the diagnosis criteria (DSM-III-R vs DSM-IV) nor the assessment instruments (the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID-I] vs Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview vs Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia) accounted for the differences in the prevalence data across the studies recruited.

Prevalence of OCD in patients with a primary diagnosis of BDD

Researches on the prevalence of OCD in adult outpatients with a primary diagnosis of BDD have been scarce relative to those undertaken in OCD samples, albeit the methodology was more heterogeneous (eg, differences in recruitment and referral methods). Regarding this issue, the lifetime prevalence of OCD within BDD samples varied considerably from 43% to 14% (mean =27.5%).Citation19–Citation23 Particularly, data from the study indicated that the highest percentage should be considered with caution because the sample consisted of predominantly women subjects, referred to hospital centers for esthetical medical treatment (vs psychiatric setting).Citation19 In addition, the study with the lowest percentage was initially composed of a drug-free sample with a primary diagnosis of major depression in which further comorbidity assessments were conducted.Citation22 Concerning the current prevalence of OCD among BDD samples, rates for this type of comorbidity were 37%–16.7% in BDD patients (mean =25.7%) relative to 8% in non-BDD patients.Citation21,Citation24–Citation26 Specifically, data from the study with the largest sample (N=293) indicated that 25% of those with BDD also had OCD.Citation21 Similar to OCD samples, neither the diagnostic criteria nor the assessment instruments explained the differences in the rates of comorbidity across the studies.

Is there any etiopathogenic pathway that may account for the comorbidity of BDD and OCD?

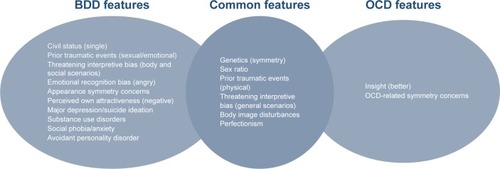

The second goal of this review was to assess potential etiopathogenic pathways that might explain the comorbidity of BDD and OCD. The main findings concerning: 1) common shared factors (genetics and environmental influences, socio-demographic profile, cognitive correlates, personality features, psychiatric comorbidity, and symptom co-occurrence); 2) one disorder being a risk factor for the other (vulnerability model); and 3) chance association (random co-occurrence) are described. The overall results from the common shared factors are illustrated in .

Common shared factors (third variables)

Genetics and environmental influences

Studies assessing rates of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis in the first-degree relatives of patients with either OCD or BDD reveal greater percentage of both disorders among their familiars, compared with the first-degree relatives of healthy subjectsCitation19 or non-OCD patients.Citation6,Citation7 In addition, these studies showed higher prevalence for mental disorders other than OCD/BDD among the first-degree relatives of OCD/BDD patients, namely, eating disorders,Citation19 social phobia,Citation7,Citation16 and major depression.Citation7,Citation13,Citation16 Except for the most recent study,Citation7 these findings should be taken cautiously because of a low statistical powerCitation6 or the absence of direct assessment of first-degree relatives by using the Family History ScreenCitation16,Citation19 or telephone procedures.Citation13

Overall, findings on psychiatric family history of patients with OCD, BDD, or both have been employed to suggest a particular link between them, specifically regarding the inclusion of both disorders into an OCDRD taxonomy.Citation27 Accordingly, further studies have been carried out to investigate whether common genetics or environmental factors could account for this potential relationship. For instance, a study within a community sample of 2,148 adult twins revealed that the covariation between BDD and OCD traits was largely accounted for by genetic influences common (64%) to both phenotypes.Citation28 This genetic overlap was even higher when specific OC symptom dimensions were considered; up to 82% of the phenotypic correlation between the obsession and symmetry-ordering symptom dimensions and BD concerns were attributable to common genetic factors. Despite these findings, the limitations of this study should be taken into account, specifically the exclusion of male twins and the use of self-report measures (Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire) instead of structured clinical interviews that could increase the risk of a false-positive diagnosis. Later, the same group of research performed a latent class analysis among 5,408 female twins (3,041 monozygotics and 2,367 dizygotics) assessed for OCDRD.Citation29 The authors found that common (vs disorder-specific) genetic influences were moderate (33%) in BDD when all the OCDRD (including OCD) were analyzed together. In addition, shared (vs non-shared) environmental risk factors in BDD were low (10%) when all the OCDRD were considered. Concerning the presence of common environmental risk factors, an additional cross-sectional study found that BDD patients reported higher rates of sexual (28% vs 2%) and emotional abuse (22% vs 6%), but similar rates of physical abuse (14% vs 8%) than OCD patients.Citation30 However, methodological flaws, such as potential recall/misinterpretation biases and the lack of standardized instruments to assess traumatic events, may have hindered the validity of these findings.

Sociodemographic profile

There is consistent evidence regarding similar sex ratios in BDD and OCD.Citation13,Citation30–Citation35 The only study that revealed significantly higher rates of BDD than OCD (65% vs 41%) in women arose from the smallest sample of all the studies collected (BDD, N=23 vs OCD, N=22). With respect to marital status, the findings are heterogeneous after controlling for age, indicating either similar marital status for both disordersCitation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34 or greater rates of BDD among unmarried/single patients.Citation13,Citation32 Methodologically noticeable, the former studies included patients with lifetime diagnoses of OCD or BDD, while the latter studies recruited patients with current diagnosis of BDD or OCD. Overall, several of these studies have not addressed whether between-group differences in the current symptom severity accounted for the findings in marital status.Citation30,Citation32,Citation34

Psychopathological features

BDD patients often spend hours each day performing ritualistic behaviors, such as excessive grooming, mirror checking, repetitive touching, excessive application of makeup, and camouflaging one’s appearance with clothing or jewelry.Citation13 These repetitive behaviors have been postulated to be similar to compulsions performed by OCD patients. Regardless of this theoretical assumption, empirical research on the potential common psychopathological features for both disorders has been focused on the degree of insight regarding OCD and BDD. Concerning this issue, cross-sectional studies have found poorer insight for BDD than for OCD in patients with comorbid conditions or in those with the former diagnosis when compared with subjects with the latter diagnosis. These findings have been consistent, irrespective of the assessment instrument used, that is, single-items from the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS),Citation14 the multidimensional approach from the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS),Citation33,Citation36–Citation38 or the Overvalued Ideas Scale.Citation39

Cognitive correlates

It has been suggested that one cognitive correlate that predisposes or maintains both BDD and OCD could be a threatening interpretive bias toward ambiguous stimuli either general or disorder specific. Regarding this theme, there is only one experimental study in which the patients chose one alternative of three possible options that attempted to follow an unfinished narrative story concerning several issues. The authors found that OCD and BDD patients exhibited a threatening interpretive bias for general scenarios relative to healthy controls, but only those with BDD reported a threatening interpretive bias for body-related scenarios and for social scenarios.Citation40 The sample size was quite small (BDD, N=19 and OCD, N=20), and there were no replication studies. Thus, this finding should be taken cautiously. In addition, other studies by the same group of researchers have been conducted to determine whether both disorders are characterized by an emotional recognition bias. With respect to this issue, one study using the facial photographs from the Ekman and Friesen’sCitation41 set evidenced that BDD individuals, relative to OCD and healthy controls, were less accurate in identifying facial expressions of emotion and more often misidentified emotional expressions as angry. This study was also carried out with a small sample (BDD, N=20 and OCD, N=20) and warrants further replication.

Other studies have addressed whether OCD/BDD patients could manifest cognitive reasoning biases that were either general or disorder specific. Regarding this issue, 20 OCD, 20 BDD, and 20 healthy controls completed a memory task assessing reality-monitoring ability for verbal stimuli (neutral, negative, BDD-related, and OCD-related stimuli), that is, the ability to discriminate between imagination and reality. There were no significant differences between the three groups for each type of stimuli in spite of a lower degree of insight in the BDD group as measured by the BABS.Citation38 Although this research has its limitations, further studies with larger samples and more ecological stimuli (images rather than words) should clarify the potential role of this cognitive ability in both disorders. In addition, this group research also assessed whether the same sample could reveal between-group differences in jump-to-conclusions reasoning bias, that is, the need to request significantly less information before making a decision. Accordingly, all participants completed two tests of probabilistic reasoning: the beads task (neutral task) and the survey task (self-relevant task). Similarly, there were no significant between-group differences, despite lower level of insight in BDD patients.Citation42

Other studies have been focused on measuring esthetic thoughts in both disorders. First, one research study showed non-personal photos displaying faces varying in attractiveness (attractive, average, and unattractive) and then other facial photos taken of the study participants. The individuals were asked to rate the photos from both phases in terms of their physical attractiveness. Similar to OCD and healthy controls, BDD patients endorsed normative ratings of beauty (standards of attractiveness), but their own perceived attractiveness was significantly lower compared with the other groups.Citation43 This study was also conducted with a small sample (BDD, N=19 and OCD, N=21) and needs further replication. In addition, one previous study with a large population comprising, among others, 100 patients with OCD and 100 individuals with BDD found that 20% of the BDD patients had an occupation or education in art or design compared with 3% of those with OCD.Citation35 The authors underlined that this finding could reflect a higher esthetic sensitivity among BDD. Notwithstanding, this interpretation should be taken cautiously because of the cross-sectional nature of this study and the use of questionnaires rather than structured clinical interviews to make the psychiatric diagnosis.

Other types of studies have focused on symmetry. An experimental study using non-personal photos varying in facial symmetry showed that 20 BDD patients reported similar perceptual ability and evaluative preference for symmetry as 20 OCD patients and 20 healthy controls.Citation44 Notwithstanding, data from similar studies with larger samples, which may incorporate manipulated patients’ faces, should be considered to determine if BDD sufferers could apply different standards to their own face than they do to others’ faces. Concerning this proposed methodology, a pilot study that used scanned photography of OCD patients, BDD patients, and healthy controls found that both clinical patients modified over 50% (vs 0% in controls) of undistorted photographs because they thought that these stimuli did not exactly reflect as they looked like.Citation45 The authors suggested that this finding indicated a similar body image disturbance in OCD and BDD, although statistical power was poor because of a very small sample (OCD, N=10 and BDD, N=10). Furthermore, another study with a large sample of 275 BDD patients found than 31% of participants reported appearance-related symmetry concerns for at least one body part with which they were preoccupied. In addition, this subset of BDD patients was more likely to have lifetime OCD in general (48% vs 25.5%), but not more lifetime OCD-related symmetry concerns specifically (36% vs 38%), suggesting different mechanisms in BDD and OCD symmetry concerns.Citation46 Notwithstanding, appearance-related symmetry concerns were measured by a single-item from the BDD data form. Thus, these findings could be limited because of the assessment instrument.

Personality features

Personality characteristics have been rarely assessed and have arisen from divergent perspectives (categorical vs dimensional approaches). On the one hand, an American study using a mixed sample (inpatients and outpatients) diagnosed with OCD (N=210) and BDD (N=45) found no significant between-group differences in the prevalence of personality disorders as ascertained by SCID-II.Citation33 The authors only evidenced higher rates (trend level) of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in OCD than in BDD individuals (26% vs 9%). Regarding OC traits, a study with a small sample (OCD, N=21 and BDD, N=19) did not reveal differences in perfectionism between OCD and BDD patients as measured by the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. However, both clinical groups reported more perfectionism than the healthy controls. On the other hand, an additional Turkish study with a moderate-sized sample, drug free before the recruitment, showed that BDD patients (N=29) were more likely than OCD patients (N=49) to have narcissistic (31% vs 6%), histrionic (38% vs 12%), and avoidant (66% vs 33%) personality disorders as measured by SCID-II.Citation34

Psychiatric comorbidity and symptom co-occurrence

Comparative rates of comorbidity in OCD and BDD have mainly focused on depressed mood (either dimensional or categorical approach), social anxiety (either dimensional or categorical approach), eating disorders, and drug misuse. Regarding depressed mood, studies have yielded mixed results. Several studies found similar rates of lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) for both clinical groups, up to 53% for each group,Citation32,Citation34 while others showed that BDD patients were more likely to have MDD relative to OCD individuals.Citation13,Citation33 Particularly, the study with the largest sample (OCD, N=210 and BDD, N=45) found significant differences of MDD comorbidity when comparing both clinical groups with a peak of 87% in BDD and 65% in OCD.Citation33 It should be underscored that, unlike the studies yielding between-group differences, those who found similar rates were conducted in non-American samples. Concerning the severity of current depressive mood as measured by questionnaires, the studies tend to reveal similar severity for OCD and BDD.Citation33,Citation34,Citation39,Citation45 The only study showing greater severity of depressive mood on BDD had a small sample (BDD, N=19 and OCD, N=20) and lacked statistical power.Citation40 In addition, relative to OCD patients, those with BDD have reported greater rates of lifetime suicidal ideation in general (78% vs 55%) because of their disorder specifically (22% vs 8%),Citation13,Citation33 but their current suicidal ideation is similar to OCD individuals (27% vs 20%).Citation32

Concerning lifetime social phobia, most of the study showed similar rates of comorbidity in OCD and BDD patients, up to 27% and 31%, respectively.Citation32–Citation34 There are research results yielding significant higher rates of lifetime social phobia in BDD than in OCD (49% vs 19%). Notwithstanding, when assessing severity of social anxiety, BDD individuals reported significant higher scores on the Fear of Negative Evaluation scale than OCD patients.Citation40 In spite of this fact, the sample size of this study was small (OCD, N=20 and BDD, N=19) and the findings need further replication.

With regard to lifetime eating disorders, the studies within American samples found similar rates among patients with a primary diagnosis of either OCD or BDD, with percentages up to 13% and 7%, respectively.Citation13,Citation33 Conversely, an Italian study found significantly higher rates of eating disorders in BDD relative to OCD patients with percentages up to 18% and 9%, respectively.Citation32

Finally, rates of comorbid lifetime alcohol-substance use disorders (SUD) have been more usually found in BDD than in OCD with the quantity of primary diagnoses up to 47% and 24%, respectively.Citation32,Citation33 The only study that showed non-significant between-group differences in alcohol-SUD used the smallest sample (OCD, N=53 and BDD, N=53).Citation13

One disorder being a risk factor for the other

One indirect approach to take to discover whether one disorder may be a risk factor for the other may be by retrospectively determining the age at the onset of both disorders, either in patients with comorbid OCD and BDD or in comparative studies of OCD vs BDD. Accordingly, if one disorder tends to appear substantially before the onset of the other, this could provide some evidence to this issue.

Regarding this theme, qualitative data from these types of studies indicate that BDD usually precedes OCD,Citation21 but, except for one research study,Citation32 quantitative data reveal that the mean age of onset for both disorders does not significantly differ (OCD =17.8 vs BDD =17.6).Citation13,Citation14,Citation17,Citation30,Citation33,Citation39

Chance association

Another heuristic approach to explain the comorbidity of OCD and BDD could be that the co-occurrence of both disorders was a clinical artifact linked to psychiatric samples. That is, the likelihood that one disorder was associated with the other would be higher in psychiatric samples than in the general population because individuals from the psychiatric samples would be more psychopathologically ill (Berkson’s bias). If so, patients within these samples should also have greater comorbidity with other mental disorders than OCD or BDD specifically.

Accordingly, several studies have addressed whether patients with a primary diagnosis of either OCD or BDD present high rates of comorbid mental disorders other than OCD or BDD. Regarding this issue, research in BDD samples has systematically showed greater rates of lifetime and current social phobia than OCD,Citation12,Citation15,Citation17,Citation22,Citation26 with the exception of one study enrolling female cosmetic surgery patients.Citation19 Specifically, the study with the largest BDD sample (N=293) found greater rates of social phobia and MDD than OCD.Citation21 The same finding was evidenced in other study carried out with a smaller BDD sample (N=54).Citation25 Concerning the studies in OCD samples, research on psychiatric comorbidity beyond BDD has been scarce. First, one study showed that current comorbidity rates of social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder were higher than BDD among obsessive patients.Citation16 In addition, two studies with larger OCD samples (N=901 and N=457) reported greater lifetime comorbidity rates of social phobia and MDD than with BDD among obsessive patients.Citation8,Citation11

Disentangling the core features of patients with comorbid BDD and OCD

The third goal of this review was to describe the core features of patients with comorbid BDD and OCD to determine both the clinical impact of one disorder on the other (eg, insight, content, severity, age at onset, and response to treatment) and the distinctive clinical characteristics of subjects with comorbid OCD and BDD relative to those with one diagnosis alone (eg, sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidity rates, and quality of life).

Findings from comparative studies between comorbid OCD–BDD and OCD patients

Impact of BDD on OCD characteristics

With regard to OCD insight, comparative studies between patients with comorbid OCD–BDD and OCD patients have found either similarCitation14,Citation47 or poorer degree of insight among those with comorbid BDD.Citation8,Citation48 Most of these studies have assessed the insight using the BABS with the exception of one study with a poorer assessment instrument that used a single-item from the Y-BOCS.Citation14 Among those evidencing between-group differences, researchers have also sought to control for confounding variables (eg, severity of OCD). Concerning this issue, one study with a large sample (N=901) showed that comorbid BDD was not associated with poorer insight into OCD,Citation8 while another smaller sample (N=103) confirmed this relationship.Citation48 Concerning OCD severity as measured by the Y-BOCS, researchers usually have found no between-group differences.Citation8,Citation14,Citation18,Citation34,Citation47,Citation48 Regarding OCD symptomatology as assessed by the Y-BOCS, comparative research has yielded mixed results – either no between-group differencesCitation47 or greater severity or presence of OC symptoms in those with comorbid BDD, such as somatic obsessions,Citation48 sexual obsessions,Citation8,Citation14 religious obsessions,Citation8 aggressive obsessions,Citation8 symmetry O/C,Citation18 hoarding O/C,Citation18,Citation48 or checking compulsions.Citation14,Citation18 In spite of these facts, only one study with 103 OCD patients showed that some OC contents (somatic and hoarding obsessions) were associated with the presence of comorbid BDD after performing a regression analysis.Citation48 Concerning age of onset of OCD, comparative studies agree; there is earlier onset among those with comorbid BDD.Citation8,Citation18,Citation48 Finally, both randomized, controlled trials with antidepressantsCitation47,Citation49 and naturalistic treatments with psychopharmacology and psychotherapyCitation14,Citation18 showed that treatment response for OCD was independent of the presence of comorbid BDD.

Distinctive, non-OCD characteristics of comorbid BDD–OCD patients

Concerning sex ratio, comparative studies show similar sex distribution between BDD–OCD and OCD patients.Citation13,Citation14,Citation31–Citation34,Citation47 Regarding civil status, studies find higher rates of single people among BDD–OCD patients (vs OCD)Citation8,Citation13,Citation18,Citation32 than no between-group differences,Citation31,Citation34 even after controlling for age.Citation32 Rates of employment and education level are consistently poorer in OCD–BDD patients relative to OCD patients.Citation8,Citation13,Citation32,Citation33,Citation48 Concerning psychiatric comorbidities, patients with BDD–OCD showed similar rates of lifetime MDD than those with OCD.Citation8,Citation13,Citation33,Citation34,Citation47 However, they also reported higher current depressive symptom severity as well as current and lifetime suicidal ideation.Citation8,Citation18,Citation32,Citation33,Citation47 Logistic regression analysis also confirmed the association between the latter two variables and comorbid BDD.Citation8,Citation33 Moreover, both lifetime social phobia and alcohol-SUD have consistently been more likely in OCD–BDD patients than in OCD individuals.Citation18,Citation32–Citation34,Citation47,Citation48 Particularly, the association between BDD comorbidity and the presence of social phobia was confirmed in OCD samples using logistic regression analysis.Citation8 Lifetime rates of eating disorders have yielded mixed results, either no between-group differences in American samplesCitation13,Citation33 or higher prevalence in BDD–OCD patients compared to OCD patients among non-American samples.Citation8,Citation32 Specifically, using logistic regression analysis, one study with a large OCD sample (N=901) revealed that BDD comorbidity was associated with the presence of eating disorders among OCD patients.Citation8 With regard to the assessment of personality disorders, the research is scarce, but tends to find greater rates of either Cluster B personality disorders or avoidant personality disorders in OCD patients with (vs without) comorbid BDD, even after controlling for OCD severity.Citation33,Citation34 Finally, as suggested by the previous results, a single study (N=250) found that the presence of BDD comorbidity was associated with a poorer quality of life among those with a primary diagnosis of OCD, even after controlling for OCD severity.Citation31 This study used several rigorous psychometric instruments such as the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation.

Findings from comparative studies between comorbid OCD–BDD and BDD patients

Impact of OCD on BDD characteristics

Research on the impact of OCD on BDD is scarce and inconclusive. With regard to the insight into BDD, one single study found lower insight in patients with comorbid OCD–BDD than in BDD patients.Citation50 However, this study used limited methodology, that is, insight was measured by a single-item from the Y-BOCS. The statistical power was low due to the sample size (N=30), and the sample was predominantly men (83%). Concerning the severity of BDD as measured by the BDD-YBOCS, one study showed greater symptom severity in comorbid patients,Citation33 while another did not find between-group differences.Citation50 The former study had a more adequate sample size (N=85 vs N=30) and was methodologically more relevant. Concerning the content of BDD as ascertained by the BDD-YBOCS, there is only one study with a moderate sample size (N=58), which evidenced greater face concerns among those with BDD alone (vs BDD–OCD patients). Comparative studies focused on the age of onset of BDD have not found between-group differences.Citation34,Citation50 Finally, both clinical trials with antidepressants and naturalistic treatments with psychopharmacology and psychotherapy showed that the presence of comorbid OCD was associated with a similar treatment response for BDD, even after controlling for confounding variables.Citation24,Citation51

Distinctive, non-BDD characteristics of BDD–OCD patients

Research on this issue is scarce and lacks methodological rigor because of the moderate sample size and the absence of secondary analysis to control for confounding variables with the exception of one study.Citation33 Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, research has consistently found similar sex ratios, numbers of married people, employment rates, and education levels in OCD–BDD and BDD patients,Citation13,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation50 even after controlling for age.Citation32 Concerning psychiatric comorbidities, studies on lifetime MDD have yielded mixed results,Citation33,Citation34 finding even lower rates of MDD among BDD–OCD patients when compared with BDD individuals.Citation13 In addition, the presence of OCD comorbidity was not associated with current depressive symptom severity as measured by questionnaires among patients with a primary diagnosis of BDD.Citation33,Citation34 Concerning lifetime and current suicidal ideation, OCD–BDD patients were more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those with BDD alone,Citation13,Citation32 but differences disappeared when controlling for BDD severity.Citation33 Despite methodological similarities between the studies, lifetime comorbidity of social phobia, eating disorders, and alcohol-SUD have yielded mixed results, either higher prevalence in BDD–OCD patientsCitation32 or similar rates in BDD–OCD and BDD patients.Citation13,Citation33,Citation34 Likewise, researches on personality disorders have also found similar rates in BDD–OCD and BDD patients.Citation33,Citation34 Finally, a single study (N=250) found that the presence of OCD comorbidity was not associated with a poorer quality of life among those with a primary diagnosis of BDD, after controlling for BDD severity.Citation31

Discussion

Prevalence of the comorbidity between OCD and BDD

Findings from this review underscore that the rates of BDD–OCD comorbidity ranges from 3% to 43% and are almost threefold higher in BDD samples than in OCD samples. How can we explain these divergences between both types of samples? We postulate that only some specific OCD symptoms, mainly symmetry obsessions, could have a relationship with BDD. This suggestion is partly supported by genetic studiesCitation28 but still has not received evidence from comparative studies (BDD–OCD vs OCD) on OCD symptomatology. Hence, further studies should investigate this issue. Furthermore, prevalence studies tend not to include a control group (healthy or non-OCD/BDD controls) when assessing rates of comorbidity of both disorders.Citation6,Citation7,Citation17,Citation26 Thus, despite high rates of this comorbidity, we cannot establish an odds ratio, and this limitation should be taken into account by future research. Besides, the studies collected arise from psychiatric samples, mainly OCD specialty clinics. Hence, the comorbidity rates may be inflated due to recruitment bias and cannot be generalized to the general population. Further research on community samples could help to obtain more accurate and firm evidence on the comorbidity rates. Likewise, clinicians should take into account that high rates of comorbidity of BDD and OCD do not necessary imply a distinctive relationship between both disorders. Indeed, prevalence studies have even found greater comorbidity with social phobia and MDD than with OCD and BDD in patients with one of the two latter diagnoses.

Is there an etiopathogenic pathway that may account for the comorbidity of BDD and OCD?

Findings from this review stress that there is still no sound evidence concerning potential etiopathogenic pathways that may explain comorbid OCD and BDD. Although methodologically flawed, retrospective studies consistently report similar age of onset for both disorders. This finding partly rules out the likelihood that one disorder was a risk factor for the other (vulnerability model), although prospective studies should be undertaken to clarify this theme. Concerning the chance association approach, findings from this review underscore that both OCD and BDD samples present high comorbid rates with other mental disorders than with each other. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily imply that there was random co-occurrence of OCD and BDD. Rather, this may suggest that BDD may represent a heterogeneous nosological category without a univocal and complete relationship with OCD. Regarding the presence of common shared factors (third variables), more divergences than similarities have been found when both disorders are directly compared. BDD patients tend to manifest a more severe clinical profile, both psychopathological and functional, when compared with OCD individuals. Additionally, many promising fields of research (eg, cognitive correlates) have not been adequately investigated and lack enough study subjects to provide compelling evidence. Moreover, other external criteria have been rarely addressed, despite yielding similar findings for OCD and BDD in independent studies. For instance, comparative studies on neurobiological (findings from limbic, visual cortex, and frontostriatal cortex), psychopharmacological, and neuropsychological correlates are almost nonexistentCitation45,Citation52–Citation55 and should be investigated by future research. Maybe, the most consistent and intriguing finding observed in comparative studies has been the low degree of insight into their disorder among BDD patients, most of whom evidence poor or lack of insight. This finding raises a clinical doubt whether appearance-related concerns in BDD patients should be considered an intrusive thought or, otherwise, an overvalued idea or a delusional thought. We thought that some indirect clues may be gathered from other comparative studies collected to partly elucidate this issue. For instance, cognitive reasoning biases traditionally observed in delusional patients (eg, jumping to conclusions and reality-monitoring deficits) have not been found in BDD individuals. In addition, there is preliminary evidence suggesting a high esthetic sensitivity in BDD patients,Citation35 which may indicate that appearance-related concerns may be egosyntonic and not a random thought. Taking into account all these findings, we suggest that appearance-related concerns in BDD patients are more closely related to overvalued ideas than to intrusive or delusional thoughts as defined by phenomenological authors.Citation56,Citation57 If so, motivational interviewing as well as inference-based therapy may be a key component in the treatment of BDD (vs OCD) patients who are not willing to change this psychopathology because of their egosyntonic features.Citation58,Citation59

Despite the fact that this review has not completely followed PRISMA guidelines,Citation60 which are currently considered the gold standard in the field, we consider that the recent integration of BDD into OCDRD needs further confirmation. Hence, we underscore that the recent inclusion of BDD within OCDRD (as classified in the DSM-5 in 2013 and proposed in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision [ICD-11]Citation61) should be taken cautiously. Alternatively, the inclusion of BDD as a type of hypochondriacal disorder (ICD-10) also seems not to collect enough evidence from empirical research.Citation62 In fact, data from these comparative studies almost provide more indirect evidence on the potential similarities between BDD and social phobia (eg, threatening interpretive bias for social scenarios, emotional recognition bias for angry expressions, comorbidity rates of social phobia and avoidant personality disorder, family loading, and so on). This assumption is in line with the Asian approach to BDD as a possible social phobia subtype (in Japanese: taijin kyofusho [fear disorder of interpersonal relationships]).Citation63 As a consequence, there is a compelling need to carry out comparative studies between OCD, BDD, and social phobia to redefine this issue. Maybe, by performing these types of studies, we can pose whether there might be two BDD profiles: a reassurance/compulsive subtype of BDD as defined in DSM-5Citation64 (with repetitive behaviors or mental acts), closely related to OCD, and a phobic (avoidant) subtype of BDD, closely related to social phobia.

Disentangling the core features of patients with comorbid BDD and OCD

Findings from this review stress that the clinical impact of one disorder (OCD or BDD) on the other is the exception rather than the rule. Notwithstanding, there is a need to undertake more comparative studies between comorbid OCD–BDD and BDD to rule out the previous assumptions. Of interest, clinicians should suspect the potential of an overlooked or hidden BDD comorbidity diagnosis when age of OCD onset is earlier than expected. Unlike OCD comorbidity in patients with a primary diagnosis of BDD, there is also consistent evidence indicating that the presence of BDD comorbidity exerts a cumulative negative impact on OCD individuals, both functional (eg, poorer quality of life, more unemployment, and living alone) and psychopathological (more comorbidity with social phobia, alcohol-SUD, Cluster B personality disorders, and suicidal ideation). Hence, clinicians usually treating OCD patients in specialty clinics should take special care of those with comorbid BDD because of their greater clinical severity and psychosocial impairment, which in turn make them more difficult to attend to in clinical settings as therapeutic adherence can be hampered by their clinical severity and dysfunctionality. Concerning this issue, an additional unexplored field of research deals with the combined treatment of OCD and BDD in those being diagnosed with this comorbidity.Citation23 This is particularly striking as a 3-year prospective study with a small sample of OCD–BDD patients preliminarily found that improvements in OCD predicted BDD remission (but not vice versa).Citation65 Hence, further research aimed at treating comorbid BDD is mandatory among OCD patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HollanderEObsessive-compulsive disorder and spectrum across the life spanInt J Psychiatry Clin Pract200592798624930787

- ChosakAMarquesLGreenbergJLJenikeEDoughertyDDWilhelmSBody dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: similarities, differences and the classification debateExpert Rev Neurother2008881209121818671665

- Díaz MársáMCarrascoJLHollanderEBody dysmorphic disorder as an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorderActas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines19962463313379054204

- PhillipsKAMcElroySLHudsonJIPopeHGJrBody dysmorphic disorder: an obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder, a form of affective spectrum disorder, or both?J Clin Psychiatry199556441517713865

- PhillipsKAKayeWHThe relationship of body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders to obsessive-compulsive disorderCNS Spectr200712534735817514080

- BienvenuOJSamuelsJFRiddleMAThe relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to possible spectrum disorders: results from a family studyBiol Psychiatry200048428729310960159

- BienvenuOJSamuelsJFWuyekLAIs obsessive-compulsive disorder an anxiety disorder, and what, if any, are spectrum conditions? A family study perspectivePsychol Med201242111321733222

- Conceição CostaDLChagas AssunçãoMArzeno FerrãoYBody dysmorphic disorder in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and clinical correlatesDepress Anxiety2012291196697522815241

- JaisooryaTSReddyYCSrinathSThe relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to putative spectrum disorders: results from an Indian studyCompr Psychiatry200344431732312923710

- JaisooryaTSJanardhan ReddyYCSrinathSIs juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? Findings from an Indian studyEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200312629029714689261

- LochnerCFinebergNAZoharJComorbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): a report from the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS)Compr Psychiatry20145571513151925011690

- LochnerCSteinDJObsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders in obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disordersPsychopathology201043638939620847586

- PhillipsKAGundersonCGMallyaGMcElroySLCarterWA comparison study of body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry199859115685759862601

- SimeonDHollanderESteinDJCohenLAronowitzBBody dysmorphic disorder in the DSM-IV field trial for obsessive-compulsive disorderAm J Psychiatry19951528120712097625473

- WilhelmSOttoMWZuckerBGPollackMHPrevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in patients with anxiety disordersJ Anxiety Disord19971154995029407269

- BrakouliasVStarcevicVSammutPObsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: a comorbidity and family history perspectiveAustralas Psychiatry201119215115521332382

- Brawman-MintzerOLydiardRBPhillipsKABody dysmorphic disorder in patients with anxiety disorders and major depression: a comorbidity studyAm J Psychiatry199515211166516677485632

- StewartSEStackDEWilhelmSSevere obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without body dysmorphic disorder: clinical correlates and implicationsAnn Clin Psychiatry2008201333338

- AltamuraCPaluelloMMMundoEMeddaSMannuPClinical and subclinical body dysmorphic disorderEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2001251310510811697569

- FontenelleLFTellesLLNazarBPA sociodemographic, phenomenological, and long-term follow-up study of patients with body dysmorphic disorder in BrazilInt J Psychiatry Med200636224325917154152

- GunstadJPhillipsKAAxis I comorbidity in body dysmorphic disorderCompr Psychiatry200344427027612923704

- NierenbergAAPhillipsKAPetersenTJBody dysmorphic disorder in outpatients with major depressionJ Affect Disord2002691–314114812103460

- PhillipsKAPaganoMEMenardWPharmacotherapy for body dysmorphic disorder: treatment received and illness severityAnn Clin Psychiatry200618425125717162625

- HollanderEAllenAKwonJClomipramine vs desipramine crossover trial in body dysmorphic disorder: selective efficacy of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor in imagined uglinessArch Gen Psychiatry199956111033103910565503

- van der MeerJvan RoodYRvan der WeeNJPrevalence, demographic and clinical characteristics of body dysmorphic disorder among psychiatric outpatients with mood, anxiety or somatoform disordersNord J Psychiatry201266423223822029732

- ZimmermanMMattiaJIBody dysmorphic disorder in psychiatric outpatients: recognition, prevalence, comorbidity, demographic, and clinical correlatesCompr Psychiatry19983952652709777278

- HollanderEObsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: an overviewPsychiatr Ann199323355358

- MonzaniBRijsdijkFIervolinoACAnsonMCherkasLMataix-ColsDEvidence for a genetic overlap between body dysmorphic concerns and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in an adult female community twin sampleAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2012159B437638222434544

- MonzaniBRijsdijkFHarrisJMataix-ColsDThe structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for dimensional representations of DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive spectrum disordersJAMA Psychiatry201471218218924369376

- NezirogluFKhemlani-PatelSYaryura-TobiasJARates of abuse in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorderBody Image20063218919318089222

- DidieERWaltersMMPintoAA comparison of quality of life and psychosocial functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorderAnn Clin Psychiatry200719318118617729020

- FrareFPerugiGRuffoloGToniCObsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: a comparison of clinical featuresEur Psychiatry200419529229815276662

- PhillipsKAPintoAMenardWEisenJLManceboMRasmussenSAObsessive-compulsive disorder versus body dysmorphic disorder: a comparison study of two possibly related disordersDepress Anxiety200724639940917041935

- TükelRTihanAKOztürkNA comparison of comorbidity in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorderAnn Clin Psychiatry201325321021623926576

- VealeDEnnisMLambrouCPossible association of body dysmorphic disorder with an occupation or education in art and designAm J Psychiatry2002159101788179012359691

- EisenJLPhillipsKAColesMERasmussenSAInsight in obsessive compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorderCompr Psychiatry2004451101514671731

- PhillipsKAPintoAHartASA comparison of insight in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Psychiatr Res201246101293129922819678

- ReeseHEMcNallyRJWilhelmSReality monitoring in patients with body dysmorphic disorderBehav Ther201142338739821658522

- McKayDNezirogluFYaryura-TobiasJAComparison of clinical characteristics in obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorderJ Anxiety Disord19971144474549276787

- BuhlmannUWilhelmSMcNallyRJTuschen-CaffierBBaerLJenikeMAInterpretive biases for ambiguous information in body dysmorphic disorderCNS Spectr20027643543615107765

- BuhlmannUMcNallyRJEtcoffNLTuschen-CaffierBWilhelmSEmotion recognition deficits in body dysmorphic disorderJ Psychiatr Res200438220120614757335

- ReeseHEMcNallyRJWilhelmSProbabilistic reasoning in patients with body dysmorphic disorderJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry201142327027621349243

- BuhlmannUEtcoffNLWilhelmSFacial attractiveness ratings and perfectionism in body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Anxiety Disord200822354054717624717

- ReeseHEMcNallyRJWilhelmSFacial asymmetry detection in patients with body dysmorphic disorderBehav Res Ther201048993694020619825

- Yaryura-TobiasJANezirogluFChangRLeeSPintoADonohueLComputerized perceptual analysis of patients with body dysmorphic disorder: a pilot studyCNS Spectr20027644444615107766

- HartASPhillipsKASymmetry concerns as a symptom of body dysmorphic disorderJ Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord20132329229824058899

- DinizJBCostaDLCassabRCPereiraCAMiguelECShavittRGThe impact of comorbid body dysmorphic disorder on the response to sequential pharmacological trials for obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Psychopharmacol201328660361124288238

- NakataACDinizJBTorresARLevel of insight and clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without body dysmorphic disorderCNS Spectr200712429530317426667

- PhillipsKAAlbertiniRSRasmussenSAA randomized placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in body dysmorphic disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200259438138811926939

- MarazzitiDGiannottiDCatenaMCInsight in body dysmorphic disorder with and without comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorderCNS Spectr200611749449816816788

- PhillipsKAPaganoMEMenardWFayCStoutRLPredictors of remission from body dysmorphic disorder: a prospective studyJ Nerv Ment Dis2005193856456716082302

- HanesKRNeuropsychological performance in body dysmorphic disorderJ Int Neuropsychol Soc1998421671719529826

- MarazzitiDDell’OssoLPrestaSPlatelet [3H]paroxetine binding in patients with OCD-related disordersPsychiatry Res199989322322810708268

- SaxenaSWinogradADunkinJJA retrospective review of clinical characteristics and treatment response in body dysmorphic disorder versus obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2001621677211235937

- RossellSLHarrisonBJCastleDJCan understanding the neurobiology of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) inform treatment?Australas Psychiatry201523436136426129816

- MullenRLinscottRJA comparison of delusions and overvalued ideasJ Nerv Ment Dis20101981353820061867

- SantínJMGálvezFMOvervalued ideas: psychopathologic issuesActas Esp Psiquiatr2011391707421274824

- BuhlmannUReeseHERenaudSWilhelmSClinical considerations for the treatment of body dysmorphic disorder with cognitive-behavioral therapyBody Image200851394918313372

- TaillonAO’ConnorKDupuisGLavoieMInference-based therapy for body dysmorphic disorderClin Psychol Psychother2013201677621793103

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementBMJ2009339b253519622551

- VealeDMatsunagaHBody dysmorphic disorder and olfactory reference disorder: proposals for ICD-11Rev Bras Psiquiatr201436suppl 1142025388608

- PhillipsKAWilhelmSKoranLMBody dysmorphic disorder: some key issues for DSM-VDepress Anxiety201027657359120533368

- KleinknechtRADinnelDLKleinknechtEEHirumaNHaradaNCultural factors in social anxiety: a comparison of social phobia symptoms and Taijin kyofushoJ Anxiety Disord19971121571779168340

- SchieberKKolleiIde ZwaanMMartinAClassification of body dysmorphic disorder – what is the advantage of the new DSM-5 criteriaJ Psychosom Res201578322322725595027

- PhillipsKAStoutRLAssociations in the longitudinal course of body dysmorphic disorder with major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social phobiaJ Psychiatr Res200640436036916309706