Abstract

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is an endocrine disease resulting from chronic exposure to excessive glucocorticoids produced in the adrenal cortex. Although the ultimate outcome remains uncertain, functional and morphological brain changes are not uncommon in patients with this syndrome, and generally persist even after resolution of hypercortisolemia. We present an adolescent patient with Cushing’s syndrome who exhibited cognitive impairment with brain atrophy. A 19-year-old Japanese male visited a local hospital following 5 days of behavioral abnormalities, such as money wasting or nighttime wandering. He had hypertension and a 1-year history of a rounded face. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed apparently diffuse brain atrophy. Because of high random plasma cortisol levels (28.7 μg/dL) at 10 AM, he was referred to our hospital in August 2011. Endocrinological testing showed adrenocorticotropic hormone-independent hypercortisolemia, and abdominal computed tomography demonstrated a 2.7 cm tumor in the left adrenal gland. The patient underwent left adrenalectomy in September 2011, and the diagnosis of cortisol-secreting adenoma was confirmed histologically. His hypertension and Cushingoid features regressed. Behavioral abnormalities were no longer observed, and he was classified as cured of his cognitive disturbance caused by Cushing’s syndrome in February 2012. MRI performed 8 months after surgery revealed reversal of brain atrophy, and his subsequent course has been uneventful. In summary, the young age at onset and the short duration of Cushing’s syndrome probably contributed to the rapid recovery of both cognitive dysfunction and brain atrophy in our patient. Cushing’s syndrome should be considered as a possible etiological factor in patients with cognitive impairment and brain atrophy that is atypical for their age.

Introduction

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is an endocrine disease resulting from chronic exposure to excessive glucocorticoids produced in the adrenal cortex.Citation1 Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting tumors, mainly of pituitary origin (Cushing’s disease), are the most common form of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome, and cortisol-secreting adrenal tumors are responsible for approximately 20% of cases of this syndrome in Western populations and for 40% in the Japanese population.Citation2,Citation3

Although endogenous or exogenous Cushing’s syndrome produces a variety of physical clinical features, such as truncal obesity, thin skin, easy bruising, proximal weakness, osteopenia, gonadal dysfunction, hypertension, and glucose intolerance, it also affects the central nervous system. Studies have shown that many patients with Cushing’s syndrome present with cognitive or psychological alterations.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4 Furthermore, several studies confirmed the occurrence of diffuse brain atrophy associated with cognitive impairment in both children and adults with all types of Cushing’s syndrome.Citation5–Citation9 Although the ultimate outcomes remain uncertain, these central nervous system alterations persist over several years even after resolution of hypercortisolemiaCitation10,Citation11 and contribute to long-term impairment in quality of life.Citation12 Here, we report a case of cognitive dysfunction with brain atrophy in an adolescent patient with Cushing’s syndrome.

Case report

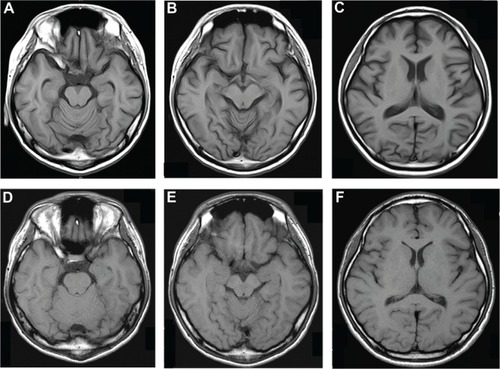

A 19-year-old Japanese male visited a local general hospital in July 2011 after 5 days of behavioral abnormalities, such as money wasting or nighttime wandering. His family history was unremarkable. He had never consumed alcohol or smoked cigarettes. He had been healthy until the appearance of a rounded face 12 months prior to the visit, and 9 months later he was found to have hypertension upon routine medical checkup. He developed insomnia, a short temper, and restlessness 1 month before the visit. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed no focal lesions but diffuse brain atrophy, including in the cerebrum, cerebellum, and hippocampus (). Because the laboratory examination showed hypokalemia and high random plasma cortisol levels (28.7 μg/dL) at 10 AM, he was referred to our hospital for further endocrine function evaluation in August 2011.

Figure 1 Transverse T1-weighted magnetic resonance images of the brain.

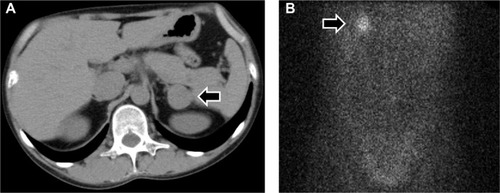

His consciousness was clear, but he presented with disorientation, planotopokinesia, and impaired reality-testing, with a global assessment of functioning score of 38 out of 100 using the Reintegration to Normal Living Index.Citation13 His height and weight were 168.8 cm and 56.3 kg, respectively. His blood pressure and pulse rate were 175/105 mmHg and 63 beats per minute, respectively, under antihypertensive treatment with olmesartan 20 mg/day. No chest rales or heart murmurs were detected. He exhibited a rounded face, thin skin, easy bruising, purple skin striae on the bilateral buttocks, and mild peripheral edema. Laboratory findings showed ACTH-independent hypercortisolemia and hypokalemia while under oral administration of 1,800 mg/day potassium chloride (). A circadian rhythm in plasma cortisol levels was absent, and plasma ACTH was undetectable. An oral dose of dexamethasone (1 mg) at 11 PM did not suppress plasma cortisol levels (25.5 μg/dL) the following morning. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated a left adrenal tumor, and 131I-adosterol scan revealed marked uptake on the same side (), suggesting a diagnosis of primary adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. His hypertension was treated with a combination of amlodipine (10 mg/day) and olmesartan (40 mg/day). Upon presentation to the psychiatric service, he was considered to have cognitive disturbance possibly due to Cushing’s syndrome, and was followed up closely without therapy.

Figure 2 Radiological findings.

Table 1 Laboratory findings in August 2011

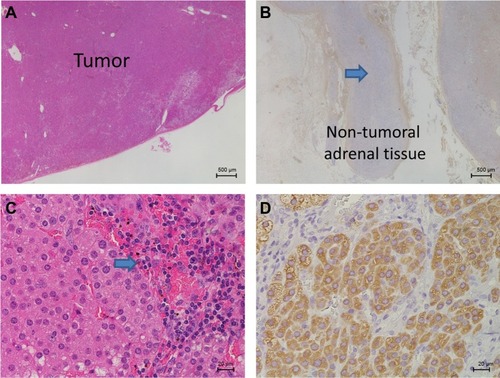

Laparoscopic left adrenalectomy was performed in September 2011. Microscopic examination was consistent with a benign cortisol-secreting adrenocortical adenoma (). Following surgery, intravenous administration of hydrocortisone was initiated, and then oral hydrocortisone (20 mg/day) was maintained. His peak plasma levels of ACTH and cortisol after intravenous corticotropin-releasing hormone (1 mg) were 5.2 pg/mL (at 30 minutes) and 0.3 μg/dL (at 60 minutes), respectively, under maintenance replacement therapy 2 weeks after surgery.

Figure 3 Histological findings of the resected left adrenal gland.

His postoperative course was uncomplicated, and his blood pressure levels and serum potassium concentration normalized without the need for medication. Behavioral abnormalities were no longer observed after surgery, and he was finally classified as cured of his cognitive disturbance caused by Cushing’s syndrome at the psychiatric service in February 2012. The Cushingoid features disappeared, and MRI of the brain performed 8 months after surgery revealed recovery of the brain volume (). The dilatation of ventricles, subarachnoid space, and sulci were also resolved, and scores for estimating ventricular volume were reduced from 0.25 to 0.22 according to the Evans’ index.Citation14 Thirty months after surgery, his right adrenal function was found to have normalized, and the replacement therapy was discontinued. His mental status improved markedly, with a Reintegration to Normal Living Index of 92 out of 100. The patient is being followed up in the outpatient clinic, and his subsequent clinical course has been uneventful.

Discussion

We described an adolescent Japanese patient with cognitive impairment and brain atrophy associated with Cushing’s syndrome, whose brain volume and cognitive function recovered rapidly after treatment of hypercortisolemia by removing cortisol-secreting adrenal adenoma.

Brain atrophy can occur in a wide variety of conditions other than aging, and notable causes include exogenous or endogenous steroids, chronic alcohol ingestion, radiation therapy, or anorexia nervosa.Citation5–Citation7,Citation15 None of the conditions other than excessive endogenous steroid hormones was present in our patient. Therefore, it is plausible that diffuse brain atrophy was caused by endogenous Cushing’s syndrome in our case.

The patient exhibited decreased brain volume in the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, including the hippocampus, along with dilatation of the ventricles, subarachnoid space, and sulci on MRI. These morphological brain changes were consistent with previously reported changes in patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome.Citation9,Citation15

The prognosis of central nervous system alterations caused by endogenous Cushing’s syndrome has been suggested to differ between adults and children. Studies of successfully treated adults with Cushing’s syndrome showed no change or only partial amelioration of cognitive impairment within 1 yearCitation16–Citation19 and partial reversal of brain atrophy with follow-up over several years.Citation20–Citation22 In contrast, a study of eleven children under the age of 16 years with Cushing’s syndrome with a mean duration of 4.4 years showed almost complete reversal of brain atrophy but a subsequent decline in cognitive function during the 1 year following correction of hypercortisolemia.Citation8 In the present case, an adolescent patient with a 1-year duration of Cushing’s syndrome experienced the reversal of cognitive dysfunction and brain atrophy within approximately 6 months following successful surgical treatment of hypercortisolemia. In addition, the patient presented no recurrent cognitive alterations during approximately 3 years post-surgery. These findings suggest that the young age at onset and the short duration of Cushing’s syndrome probably contributed to the rapid reversibility of both cognitive dysfunction and brain atrophy in our case. Long-term follow-up is, however, required, especially with regard to cognitive function.

The pathogenesis of brain atrophy in Cushing’s syndrome is thought to be multifactorial, and possible explanations include loss of water content in brain tissue, catabolic effects on proteins, reduction in glucose metabolism, synaptic accumulation of glutamate, or neuronal cell death.Citation6,Citation9,Citation15 The present case did not provide information about the precise mechanisms.

Conclusion

We reported a case of reversible brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in a patient with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome. The young age at onset and the short duration of Cushing’s syndrome may have contributed to the rapid reversibility of both cognitive dysfunction and brain atrophy in our case. The prevalence of brain atrophy in patients with Cushing’s syndrome remains unknown. The presence or absence of causal links between brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in chronic hypercortisolemia is also unclear. However, clinicians may consider Cushing’s syndrome as a possible causal condition in patients with cognitive impairment and brain atrophy that is atypical for their age.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Hiroyuki Usuda (Nagaoka Red Cross Hospital, Japan), Dr Takashi Maekawa, and Dr Hironobu Sasano (Tohoku University, Japan) for their pathology investigation. We also thank Dr Naoyuki Kojima (Niigata Medical Center, Japan) and Dr Kyuzi Kamoi (Joetsu General Hospital, Japan) for their excellent advice.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Newell-PriceJBertagnaXGrossmanABNiemanLKCushing’s syndromeLancet200636795221605161716698415

- ArnaldiGAngeliAAtkinsonABDiagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statementJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200388125593560214671138

- MiyachiYPathophysiology and diagnosis of Cushing’s syndromeBiomed Pharmacother200054Suppl 1S113S117

- SoninoNFalloFFavaGAPsychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s syndromeRev Endocr Metab Disord20101129510419960264

- MomoseKJKjellbergRNKlimanBHigh incidence of cortical atrophy of the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres in Cushing’s diseaseRadiology19719923413485553570

- HeinzERMartinezJHaenggeliAReversibility of cerebral atrophy in anorexia nervosa and Cushing’s syndromeJ Comput Assist Tomogr197714415418615219

- BentsonJRezaMWinterJWilsonGSteroids and apparent cerebral atrophy on computed tomography scansJ Comput Assist Tomogr1978211623670467

- MerkeDPGieddJNKeilMFChildren experience cognitive decline despite reversal of brain atrophy one year after resolution of Cushing syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Meta200590525312536

- BourdeauIBardCForgetHBoulangerYCohenHLacroixACognitive function and cerebral assessment in patients who have Cushing’s syndromeEndocrinol Metab Clin North Am200534235736915850847

- ResminiESantosAGómez-AnsonBVerbal and visual memory performance and hippocampal volumes, measured by 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging, in patients with Cushing’s syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201297266367122162471

- RagnarssonOBerglundPEderDNJohannssonGLong-term cognitive impairments and attentional deficits in patients with Cushing’s disease and cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma in remissionJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2012979E1640E164822761462

- LindsayJRNanselTBaidSGumowskiJNiemanLKLong-term impaired quality of life in Cushing’s syndrome despite initial improvement after surgical remissionJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200691244745316278266

- Wood-DauphineeSLOpzoomerMAWilliamsJIMarchandBSpitzerWOAssessment of global function: The Reintegration to Normal Living IndexArch Phys Med Rehabil19886985835903408328

- TomaAKHollEKitchenNDWatkinsLDEvans’ index revisited: the need for an alternative in normal pressure hydrocephalusNeurosurgery201168493994421221031

- SimmonsNEDoHMLipperMHLawsERJrCerebral atrophy in Cushing’s diseaseSurg Neurol2000531727610697236

- MartignoniECostaASinforianiEThe brain as a target for adrenocortical steroids: cognitive implicationsPsychoneuroendocrinology19921743433541332100

- MauriMSinforianiEBonoGMemory impairment in Cushing’s diseaseActa Neurol Scand199387152558424312

- ForgetHLacroixACohenHPersistent cognitive impairment following surgical treatment of Cushing’s syndromePsychoneuroendocrinology200227336738311818172

- DornLDCerronePCognitive function in patients with Cushing syndrome: a longitudinal perspectiveClin Nurs Res20009442044011881698

- StarkmanMNGiordaniBGebarskiSSBerentSSchorkMASchteingartDEDecrease in cortisol reverses human hippocampal atrophy following treatment of Cushing’s diseaseBiol Psychiatry199946121595160210624540

- BourdeauIBardCNoëlBLoss of brain volume in endogenous Cushing’s syndrome and its reversibility after correction of hypercortisolismJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20028751949195411994323

- GnjidićZSajkoTKudelićNReversible “brain atrophy” in patients with Cushing’s diseaseColl Antropol20083241165117019149224