Abstract

Individual patients with depression present with unique symptom clusters – before, during, and even after treatment. The prevalence of persistent, unresolved symptoms and their contribution to patient functioning and disease progression emphasize the importance of finding the right treatment choice at the onset and the utility of switching medications based on suboptimal responses. Our primary goal as clinicians is to improve patient function and quality of life. In fact, feelings of well-being and the return to premorbid levels of functioning are frequently rated by patients as being more important than symptom relief. However, functional improvements often lag behind resolution of mood, attributed in large part to persistent and functionally impairing symptoms – namely, fatigue, sleep/wake disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction. Thus, patient outcomes can be optimized by deconstructing each patient’s depressive profile to its component symptoms and specifically targeting those domains that differentially limit patient function. This article will provide an evidence-based framework within which clinicians may tailor pharmacotherapy to patient symptomatology for improved treatment outcomes.

Defining depression

Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder and the leading cause of disability worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 In the US, about 7%–9% of the adult population experiences a major depressive episode (MDE) each year and an estimated 8 million (3.4%) meet criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).Citation3–Citation5 The cognitive, emotional, and physical symptoms of depression translate to considerable impairments in psychosocial functioning across physical, social, and educational/occupational domains.Citation6,Citation7 Indirect workplace costs alone, characterized by low productivity (presenteeism) and days missed (absenteeism), account for over 60% of the total economic burden of depression and twice as much as that attributed to direct medical costs.Citation8

The likelihood of long-term treatment success is improved with early and accurate diagnosis, continual multidimensional assessment, and rational pharmacotherapy tailored to the patient’s symptomatology, coexisting disorders, and treatment needs.Citation9 Yet achieving these outcomes is confounded by the personal and multidimensional nature of the disease itself. There are no validated biological tests that can be used to diagnose depression. Further, without objective outcomes measures, clinicians must gauge treatment response and make clinical decisions over time based on subjective impressions of patient-reported symptoms.Citation9–Citation11

Validated assessment tools (eg, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D24]) based on core criteria ()Citation12 can facilitate the categorical diagnosis of depression and help track the presence and severity of symptoms at each visit.Citation11,Citation13,Citation14 However, clinicians may find it more practical to ask about symptoms directly through the course of the patient interview. Direct questioning combined with a clinical impression formed by the patient’s speech, affect, and appearance can help define how individual symptoms adversely affect patient-specific functioning and quality of life (QoL). If the symptom profile of an MDE is not properly assessed before and during a well-orchestrated antidepressant trial, ongoing symptoms may not be easily distinguished from treatment-related side effects or from those due to comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions.Citation15–Citation18 About half of patients who report normal functioning consider themselves to be in remission from depression despite persistent depressive symptoms.Citation19 Therefore, understanding the relationship between the symptoms of depression and how they adversely affect patient functioning is essential for optimized clinical decision making.

Table 1 DSM-5 criteria for MDE

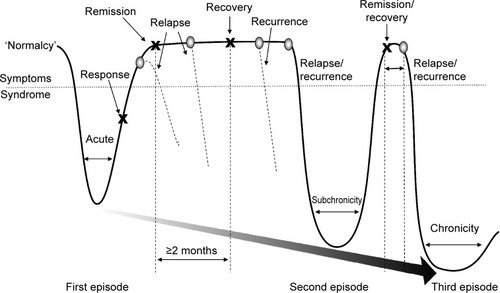

Defining recovery

The gold standard for treatment is the full resolution of symptoms and associated improvements in function and QoL.Citation9,Citation11,Citation14 While response to treatment implies a clinically meaningful degree of symptom reduction (typically defined as ≥50% reduction in pretreatment symptom severity), remission and recovery require that the symptoms of depression be absent or close to it ().Citation20–Citation22 Many clinical studies define remission as low scores on rating scales, which is not equivalent to an asymptomatic state.Citation23,Citation24 Further, as depressed mood and loss of interest generally overshadow other symptoms of depression, when mood improves, patients may misguidedly be considered in remission. In fact, most patients considered ‘in remission’ do not actually achieve complete resolution from all symptoms, even after multiple treatment steps, and often show greater depressive illness burden as symptoms persist.Citation24–Citation27 The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study of nearly 4,000 ‘real-world’ outpatients reported a cumulative remission rate of 67% after four treatment steps; however, about 70% relapsed within 1 year.Citation25 depicts a schematic representation of the progressive nature of depression, and illustrates the need for achieving and sustaining full symptom recovery early in disease pathogenesis.Citation22

Figure 1 Schematic representation of major depression.

Abbreviation: MDE, major depressive episode.

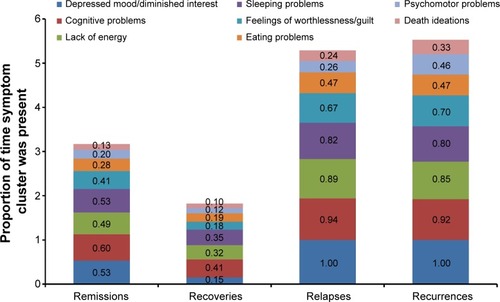

Symptoms that persist during remission are associated with relapse, recurrence, and ultimately, treatment resistance.Citation15,Citation27,Citation28 During a 3-year prospective study of 267 depressed patients, Conradi et al assessed the weekly presence of individual symptoms during each phase of depression ().Citation29 Study participants who relapsed within 8 weeks reported a greater overall symptom severity during the remission period than those who remained in remission for greater than 8 weeks (ie, in recovery). Gradual accumulation of subthreshold symptoms over time appeared to trigger the relapse, suggesting that the initial MDE had not resolved and remained subsyndromal only temporarily. In fact, patients with unresolved depressive symptoms are three times as likely to relapse as patients with asymptomatic recovery.Citation28

Figure 2 Duration of symptoms during remissions, recoveries, relapses, and recurrences.Citation29

Abbreviation: DSM-4, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

The prevalence of unresolved symptoms and their contribution to disease progression emphasize the importance of finding the right treatment choice at the onset and switching medications if necessary based on suboptimal responses. Moreover, feelings of well-being and the return to premorbid levels of functioning are frequently rated by patients as more important than symptom relief, yet functional improvements often lag behind resolution of mood.Citation6,Citation30 Reasons for delayed functional recovery are only partly characterized; however, the symptoms that most impair function are the same symptoms that commonly persist despite treatment, namely fatigue, sleep/wake disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction.Citation6,Citation18,Citation29,Citation31–Citation33 For example, patient self-reports frequently identify fatigue and low energy, insomnia, and concentration and memory problems as especially disruptive to occupational and global functioning.Citation6,Citation32 In the seminal study by Conradi et al (), patients exhibited problems with cognition 60% of the time during periods of remission compared with 41% during periods of recovery.Citation29 Similarly, a lack of energy was reported nearly half of the time during remission but only one-third of the time during recovery. These data suggest that antidepressant selection based, in part, on the most disabling patient-reported symptoms may help optimize treatment outcomes and add to a growing body of evidence on the importance of initial and ongoing individualized assessment.Citation9 highlights the MDD-associated symptoms that may co-occur during depressive episodes or persist during remission.Citation34–Citation47 While additional studies are needed to gauge the most effective treatments for these symptoms, includes select approaches with demonstrated efficacy.Citation34–Citation47

Table 2 Possible pharmacotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of select symptoms in MDD

The neurobiology of depression

The biological basis of mood disorders, in general, includes genetic, epigenetic, biochemical, and psychosocial factors.Citation48–Citation50 Precisely how these factors interact over time is not firmly established, but recent insights into the structure and function of discrete brain regions offer an opportunity to characterize the neural basis of depression and its idiosyncratic course, clinical presentation, and treatment responsiveness.Citation51,Citation52 Underlying each depressive symptom may in fact be a unique mechanism comprising multiple malfunctioning neural circuits.Citation53,Citation54 Structural and/or functional alterations have been identified in brain regions involved in emotional processing as well as cognitive control, learning, and/or memory formation.Citation51,Citation55

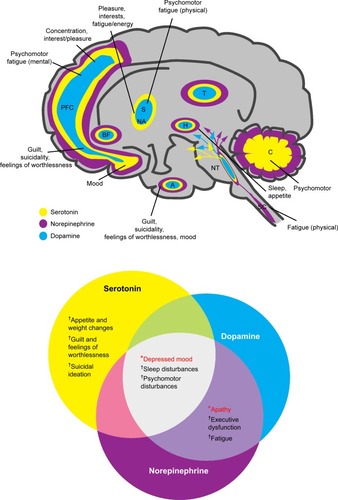

Notably, reduced hippocampal volume is common among depressed patients and directly correlates with frequency and length of depressive episodes.Citation52,Citation56 The hippocampus plays a salient role in explicit memory formation, homeostatic adaptation to stressful stimuli, and emotion processing.Citation55 Hippocampal volume reductions were found to occur after disease onset, emphasizing the importance of early treatment to minimize disease progression.Citation57 Further, discrete brain regions of depressed patients – including the prefrontal and limbic areas – demonstrate differential metabolic rates, reflecting aberrant neural activity thought to contribute to depressive symptomatology.Citation58 In addition to structural changes, alterations in neural function in the brain are also implicated in the neurobiology of MDD. A recent neuroimaging study that investigated reduced gray matter volume in the parietal–temporal regions and functional alterations in the temporal regions and cerebellum in patients with MDD suggested that structural and functional deficits contributed independently to the neurobiology of the disease.Citation59 While the relationship between altered brain structure and function and MDD symptoms remains an active area of research, the data increasingly suggest that core criterion symptoms of depression can be mapped to these and other regions of the brain ().Citation60–Citation62

Figure 3 Neurotransmitters and their hypothetically malfunctioning brain circuits in regions associated with the diagnostic symptoms for depression.

Abbreviations: A, amygdala; BF, basal forebrain; C, cerebellum; H, hypothalamus; NA, nucleus accumbens; NT, neurotransmitter centers; PFC, prefrontal cortex; S, striatum; SC, spinal cord; T, thalamus.

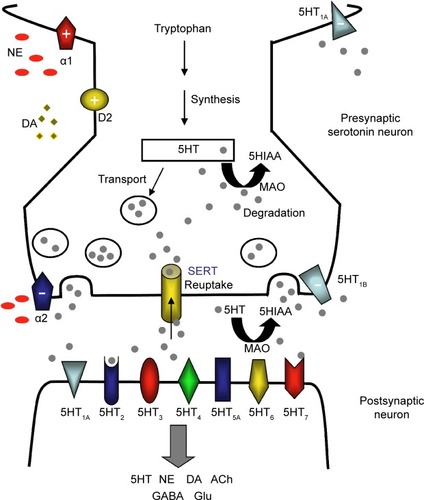

The structure and function of these brain regions are modulated by monoaminergic neurotransmission. The serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA) systems originate from the brainstem and each project to select brain regions ().Citation60,Citation61,Citation63,Citation64 The interdependent biological actions of 5HT, NE, and DA are mediated by their cognate transporters and receptors.Citation64–Citation66 For example, the serotonin 5HT2A and 5HT2C receptor subtypes inhibit postsynaptic connections on the NE and DA systems, respectively.Citation64 D2-like receptor subtypes and alpha-1 adrenoceptors can positively influence 5HT neurotransmission while presynaptic alpha-2 adrenoceptors are thought to dampen 5HT signaling ().Citation64,Citation67–Citation69 Further, in addition to directly influencing extracellular monoamine levels, postsynaptic 5HT receptors (eg, 5HT1A, 5HT3, 5HT7) modulate inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) interneurons, which in turn affect the release of 5HT itself, acetylcholine (ACh), NE, DA, and glutamate (Glu) ().Citation67,Citation69,Citation70

Figure 4 The serotonergic synapse.

Abbreviations: 5HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin; ACh, acetylcholine; DA, dopamine; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; Glu, glutamate; MAO, monoamine oxidase; NE, norepinephrine; SERT, serotonin transporter.

Interconnected monoaminergic neurotransmission provides a neural basis for mood, reward, pleasure, motivation, and related cognitive and executive functions.Citation64 Critically, disturbances in the functional connectivity in these and related neural networks appear to be integrally involved in the onset and progression of major depression.Citation64 Aberrant DA and NE signaling is thought to adversely influence motivation, an essential driver of goal-directed behaviors and related executive functions.Citation65,Citation66 Impaired 5HT neurotransmission forms, at least in part, the pathophysiologic basis for anhedonia, guilt, and similar ‘negative affects’ of depression.Citation61 Further, 5HT and NE have descending spinal pathways that mediate physical fatigue and related somatic symptoms.Citation71 Of note, numerous studies have demonstrated an increased risk for depression linked to genetic polymorphisms of 5HT, NE, or DA receptor subtypes and transporters.Citation48

While the particulars are extraordinarily complex and still only partly understood, monoamine signaling clearly exerts profound ‘downstream’ effects – both inhibitory and stimulatory – on interconnected neural networks, disturbances of which can manifest as depressive symptoms and contribute to disease progression.Citation52 Importantly, these and related biochemical lesions provide a mechanistic rationale for antidepressant therapy. Emerging data now support the very real prospect of individualized pharmacotherapy. For example, neuroimaging studies have shown that antidepressants can reverse functional changes observed in depressed patients.Citation58 These and related advances in translational research are beginning to characterize the neurobiological correlates of antidepressant treatment responses.Citation64 While we are not yet at a stage to characterize lesions on a patient-by-patient basis, we can nevertheless build a conceptual framework within which clinicians can compare individual antidepressant medications and, based on empirical observations of treatment response, adjust therapeutic strategies accordingly.

Monoaminergic pathways as drug targets

Current first-line treatment options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs).Citation9,Citation14 While the precise mechanisms by which these agents achieve their antidepressant effects are only partly characterized, subtle changes in monoaminergic neural systems clearly play an important role. More precisely, these drugs selectively inhibit the serotonin transporter (SERT), the NE transporters (NET), and/or the DA transporters (DAT), and thereby increase synaptic concentrations of their respective monoamines, which in turn affect the activity of interconnected neurotransmitter systems. However, there may be some mechanistic overlap between classes of antidepressants, and individual agents demonstrate subtle yet clinically relevant pharmacologic differences ( and ).Citation63,Citation72–Citation74 And while all SSRIs chiefly inhibit SERT, select agents also influence NE and DA neuronal activity – for example, paroxetine weakly inhibits NET and sertraline weakly inhibits DAT.Citation72,Citation75 Further, although paroxetine and fluvoxamine have similar half-lives, paroxetine, which also binds to cholinergic receptors and NET, is ten times as likely to elicit withdrawal reactions (ie, SSRI discontinuation syndrome).Citation77

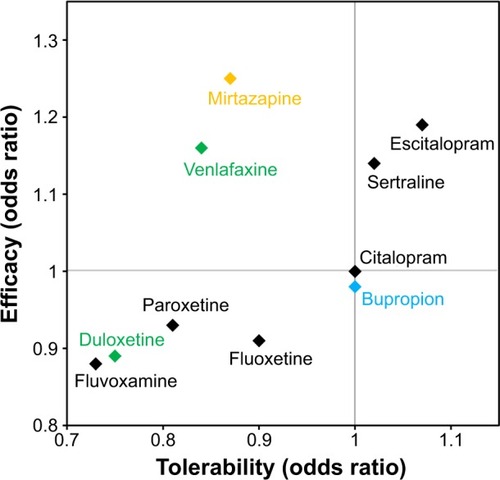

Figure 5 Efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants versus citalopram.

Abbreviations: NDRI, norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Table 3 Potential targets of first-line and emerging antidepressants

The clinical manifestation of these pharmacologic differences was recently illustrated in a meta-analysis of 117 randomized controlled trials (25,928 participants) comparing clinical response and discontinuation rates of antidepressants.Citation73 Using citalopram as the reference compound, the odds ratio (OR) for an SSRI initiating a treatment response ranged from a lower likelihood with escitalopram (OR: 0.68) to a higher likelihood with reboxetine (OR: 1.72); while tolerability ranged from a lower likelihood of tolerance with mirtazapine (OR: 0.42) to a higher likelihood of tolerance with escitalopram (OR: 1.17).Citation73 Differences were also observed between the two SNRIs – duloxetine and venlafaxine – included in the study ().Citation73 These data highlight the importance of balancing the known efficacy of a drug with its side effect profile, and the potential benefits gained from switching to another antidepressant, even within the same class.

In fact, recent studies have demonstrated that the initial choice of antidepressant medication and self-reported symptomatic improvement over 2 weeks are predictive of treatment outcomes.Citation78,Citation79 Yet the criteria by which to select the initial antidepressant have not been well-defined. This does not translate, however, into a strictly arbitrary choice. Careful alignment of patient symptomatology with the biochemical pharmacology of antidepressants can help clinicians tailor therapy. While symptom resolution is the primary driver, the efficacy of a chosen antidepressant should be weighed against other patient-specific factors such as functional goals and expectations, comorbid conditions, and concerns about side effects (eg, weight gain, sedation) and treatment costs.

Mechanism-based prescribing

Interrelationships between clinical symptoms, affected neural systems, and antidepressant mechanisms of action may help clinicians customize pharmacotherapy to a patient’s unique clinical profile.Citation54 As noted, fatigue, sleep/wake disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction are among the most troublesome symptoms, as they commonly persist after antidepressant therapy and have a disparate impact on patient functioning.Citation18,Citation29,Citation31,Citation80 Clinicians may wish to identify and specifically target these and other baseline symptoms to facilitate asymptomatic remission and thereby minimize the associated risk of relapse and recurrence.

Results from STAR*D and other studies underscore the importance of therapeutic adjustments tailored to initial and ongoing monitoring.Citation27 Most patients do not respond to the initial antidepressant regimen or are nonadherent because of side effects.Citation27,Citation81 Nonadherence with antidepressant medications is as high as 52% in patients with MDD,Citation82 with inefficacy, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain the most cited reasons for discontinuation.Citation81 Physicians may wish to adjust the dose of the initial antidepressant, switch to an alternative medication, or consider adjunctive treatment.Citation83 Nearly one-third of patients who fail an initial SSRI treatment may respond well to another antidepressant.Citation27 Adjunctive therapy predominantly includes psychotherapy and combination drug treatment. A second antidepressant with a different mechanism of action or an atypical antipsychotic can be added to the treatment plan.Citation9,Citation14 Evidence-based adjunctive treatment strategies have been reviewed elsewhere.Citation9,Citation84,Citation85 As treatment options continue to evolve, many primary care providers prefer to consult psychiatrists for guidance on switch and augmentation treatment strategies.Citation86

The simplicity and safety of monotherapy are frequently cited by patients and clinicians who prefer to avoid combination therapy or adjunctive treatment with atypical antipsychotics. Novel monotherapeutic agents that engage multiple targets may therefore provide an attractive option with the potential to ameliorate functionally impairing symptoms and reduce side effects. Interestingly, genetic variations explain an estimated 50% of an antidepressant’s efficacy.Citation48 These and related data support the development of multimodal agents that target multiple gene products, each a validated target for therapeutic intervention that may maximize the likelihood of eliciting a response.Citation54

Triple reuptake inhibitors block SERT, NET, and DAT (), and may address potential disturbances across three neurotransmitter circuits and their associated depressive symptoms simultaneously ().Citation87 However, the degree of activity at each transporter needs to be considered – too much DAT inhibition may render the drug potentially abusable, whereas too little SERT inhibition may provide insufficient antidepressant action. Amitifadine inhibits SERT, NET, and DAT with a potency ratio of 1:2:8, respectively, and is currently in clinical trials.Citation88

Multimodal drugs interact with both transporters and membrane-bound receptors, employing two distinct modes of neural signaling that may improve symptomatic resolution and reduce treatment-related side effects. The recently approved drugs vilazodone and vortioxetine exhibit SERT inhibition and 5HT1A agonism ().Citation89,Citation90 5HT1A receptors play a critical autoregulatory role in the synthesis and release of serotonin. Continuous treatment with SSRIs desensitizes 5HT1A autoreceptors, leading to enhanced serotonergic neurotransmission. However, 5HT1A desensitization generally requires 2 weeks, which may account for the delayed onset of traditional SSRIs.Citation91 Multimodal agents with 5HT1A agonist activity should therefore accelerate treatment response. Preclinical studies support this model: vortioxetine treatment desensitizes 5HT neuronal firing after only 1 day (vs 14 days with fluoxetine).Citation92 In one clinical trial, reduction in depressive symptoms was observed after 1 week of treatment with vilazodone, although the findings were not replicated in a second study.Citation93 Vortioxetine is also a 5HT1D, 5HT3, and 5HT7 receptor antagonist and 5HT1B receptor partial agonist. Interestingly, current and emerging research suggests that 5HT7 receptors play an important if partly characterized role in cognition and sleep, and are thought to reflect their effects on Glu and serotonin signaling in cortical and subcortical circuits, among other areas of the brain.Citation69,Citation94–Citation97 Through these multimodal mechanisms, vilazodone and vortioxetine can modulate downstream effects of 5HT on interconnected neurotransmitter systems. Further, clinical studies with vilazodone and vortioxetine have demonstrated favorable side effect profiles with minimal reports of sexual dysfunction and weight gain.Citation96–Citation100 Additional long-term studies are required to further evaluate the clinical relevance of these pharmacologic properties.

Cognition

The diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness is one of the core diagnostic features of depression ()Citation12 and among the most frequently persisting and functionally debilitating symptoms following treatment.Citation29,Citation80,Citation101 All domains of cognition are worse in patients with depression than in healthy controls, and many – including immediate memory, attention, ideation fluency, and visuospatial function and learning – continue to adversely affect life functioning despite improvement of depressive symptoms.Citation80,Citation102,Citation103 In a recent systematic review, nine of eleven studies reported that patients with remitted unipolar depression had decreased performance on neuropsychological tests compared with never depressed controls.Citation104 Sustained cognitive impairments following an MDE frequently lead to frustration, low self-esteem, and impaired interpersonal relationships in the family, workplace, and social network.Citation6,Citation105 Further, cognitive dysfunction is associated with the cumulative duration of depressive episodes, emphasizing the need for early detection and targeted treatment.Citation106

While additional studies are required to elucidate the neurochemical basis of persistent cognitive deficits, recent imaging studies suggest that hypoactive frontal and prefrontal cortices contribute to the diminished ability to think, concentrate, or make decisions.Citation107,Citation108 Numerous neurotransmitters – including 5HT, DA, NE, ACh, and Glu – shape the activity of procognitive circuits and provide insights into mechanism-based treatments that may be more likely to reduce cognitive impairment in depression.Citation53,Citation64,Citation70 For example, the decreased dopaminergic activity associated with depressive symptoms suggests that increasing DA activity may reduce cognitive impairment in depression.Citation54 Indeed, drug combinations with DA agonists like pramipexole as add-on treatments to antidepressants in patients with affective disorders have been shown to improve cognition in some studies.Citation109 Glu, especially, is essential for cognitive processing, and therapeutic agents that modulate Glu transmission, such as the N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists memantine and ketamine, have demonstrated antidepressant-like properties; follow-up studies in depressed patients have shown conflicting neurocognitive effects, however.Citation110,Citation111 5HT action across discrete 5HT receptor subtypes is thought to modulate GABAergic interneurons that influence Glu circuits involved in cognitive functions.Citation70 Vortioxetine, with known effects on 5HT1A, 5HT1B, 5HT1D, 5HT3, and 5HT7, has demonstrated procognitive effects in various placebo-controlled clinical trials.Citation90 In a recent study, vortioxetine-treated patients demonstrated significant improvements versus placebo in the digit symbol substitution test, an objective measure of cognitive performance, as well as in verbal learning and memory (as measured by improved scores in the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test [RAVLT]); the active reference duloxetine only showed significant improvement in RAVLT scores versus placebo.Citation112 Both duloxetine (ΔHAM-D24 −5.5, P<0.0001) and vortioxetine (ΔHAM-D24 −3.3, P=0.0011) demonstrated significant antidepressant effects versus placebo.Citation112

Cognitive function and its impact on patient function should be assessed in all patients with depression and monitored throughout treatment. While clinicians generally gauge the presence or absence of symptoms based on patient report, assessment tools, such as the six-item British Columbia Cognitive Complaints Inventory (BC-CCI),Citation113 may help if the patient is unresponsive. The independent and lasting effects that cognitive impairment has on functional improvement highlight the importance of treating cognitive impairment at baseline and for defining recovery. Further, these insights reinforce the need for well-designed studies with active comparator arms to establish definitive conclusions about differential procognitive benefits between medications.

Fatigue

Fatigue or loss of energy is a defining criterion for depression ().Citation12 The severity of fatigue reported by patients with MDD independently correlates with the severity of depression (P=0.028),Citation111 which often persists following resolution of depressed mood, and markedly impairs psychosocial functioning and QoL.Citation29,Citation114–Citation117

The prevalence of fatigue and loss of energy despite antidepressant treatment highlights the need for additional treatment options targeting the diverse neurobiology underlying psychomotor retardation, painful somatic symptoms, and executive dysfunction. Treatment-related side effects can complicate treatment as well. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and some SSRIs and SNRIs demonstrate sedative effects and can induce or exacerbate symptoms of fatigue and related functional impairments.Citation117

Descending 5HT and NE fibers in the spinal cord may regulate the perception of physical tiredness, while mental fatigue is regulated at the cortical level by several key neurotransmitters (eg, NE, DA, ACh, histamine).Citation53 In addition, both 5HT and DA projections to the striatum and 5HT and NE projections to the cerebellum regulate psychomotor functioning ().Citation115,Citation118 Inhibition of NET and/or DAT by venlafaxine, bupropion, and sertraline () can modulate NE and/or DA neurotransmission, offering advantages over SERT inhibition alone. When patients present with fatigue at baseline, clinicians should select antidepressants less likely to have sedating effects (eg, venlafaxine, bupropion, sertraline). A pooled analysis showed that bupropion is associated with lower levels of residual fatigue compared with the SSRIs.Citation119 An alternative treatment strategy is to use adjunctive therapy that targets fatigue directly with medications by increasing NE and/or DA neurotransmission; agents such as psychostimulants, the NE reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine, or lower doses of atypical antipsychotics may alleviate fatigue by promoting improved nighttime sleep quality and quantity.Citation54,Citation115,Citation117 Clinical studies evaluating the effects of multimodal agents on fatigue and related outcomes have been encouraging, though additional longitudinal studies of agents with comparable antidepressant efficacy are needed with larger patient populations.

Sleep/wake

Disruptions in circadian rhythms and the sleep/wake cycle are experienced in nearly all patients with depression.Citation120 Even after treatment, sleep/wake problems – particularly insomnia or hypersomnia – commonly persist.Citation18,Citation29 Depression is associated with both long and short sleep durations, as well as over-or underestimation of sleep time.Citation121 Compared with patients demonstrating good sleep/wake quality, those with sleep/wake problems and comorbid depression have significantly worse QoL, more functional impairments, and when accompanied by nightmares, increased risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.Citation122 Moreover, sleep/wake disturbances – including insomnia and sedation – have also been reported as side effects of common antidepressants (eg, paroxetine, venlafaxine).Citation123,Citation124 These data highlight the essential need to assess sleep/wake quality and quantity before, during, and even after treatment with antidepressants.

Sleep/wake disturbance can be mapped to dysfunction in the hypothalamus (). States of arousal are regulated by the hypothalamic sleep/wake switch and brainstem monoamine projections to the cortex.Citation125 Serotonin, histamine, and GABA each play a role in regulating normal wakefulness and sleep and can be modulated with appropriate treatment. Specifically, serotonin 5HT2A and 5HT7 receptors have been linked to sleep, circadian rhythm, and mood.Citation94,Citation121 The 5HT2A antagonist properties of trazodone () likely contribute to its known sleep-promoting effects.Citation126,Citation127 Doxepin, a TCA approved for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and insomnia, antagonizes histamine H1 receptors and is beneficial as an add-on treatment with antidepressant therapy in depressed patients with comorbid insomnia or anxiety.Citation128,Citation129 Hypnotic medications (eg, zolpidem, zaleplon) are GABAA receptor allosteric modulators that potentiate GABA neurotransmission to promote sleep.Citation128 When sleep problems emerge with treatment, switching to another antidepressant or adding a hypnotic medication may be beneficial.Citation9 Further, sedating antidepressants should be avoided in patients with hypersomnia. Additional studies are needed – particularly well-designed head-to-head studies – to evaluate the differential effects of antidepressants on sleep/wake disturbances. Interestingly, the therapeutic effects of melatonin receptor agonists like agomelatine (not currently approved in the US), which have sleep-promoting, antidepressant, and anxiolytic properties, are currently an active area of research.Citation129–Citation134 However, the implications of melatonergic agents for clinical practice have yet to be fully realized.

Conclusion

A complete baseline assessment of depressive symptoms before initiating treatment provides a patient-specific profile from which the therapeutic plan may emerge. Clarifying the prior medication history is essential to differentiate between unresolved residual symptoms, comorbid conditions, and treatment-emergent side effects. By understanding the nature and magnitude of functional impairment, physicians can formulate treatment regimens based on realistic treatment goals. Further, the symptoms and symptom clusters can, with some degree of precision, be aligned with the pharmacologic actions of current and emerging antidepressants. An operational understanding of the neural systems and targets engaged by each agent at clinically relevant doses can help physicians customize pharmacotherapy to a patient’s unique constellation of symptoms. Such mechanism-based pharmacotherapy is the linchpin of personalized treatment, and provides a rational basis on which to make initial therapeutic choices for newly diagnosed patients, and those struggling with unremitting symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, was provided by Bomina Yu, PhD, of inVentiv Medical Communications during the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure

Philip F Saltiel, MD, has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly and Company for lectures and presentations. Daniel I Silvershein, MD, has received honoraria from King Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Pfizer Inc. for lectures and presentations.

References

- PenninxBWMilaneschiYLamersFVogelzangsNUnderstanding the somatic consequences of depression: biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profileBMC Med20131112923672628

- MarcusMYasamyMTvan OmmerenMChisholmDSaxenaSWHO Department of Mental Health and Substance AbuseDepression: A Global Public Health ConcernGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2012 http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012pdfAccessed August 12, 2013

- KesslerRCChiuWTDemlerOMerikangasKRWaltersEEPrevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562661762715939839

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Current depression among adults – United States, 2006 and 2008MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201059381229123520881934

- HowdenLMMeyerJAAge and Sex Composition: 2010. 2010 Census BriefsWashington, DCUS Census Bureau2011 Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdfAccessed August 12, 2013

- McKnightPEKashdanTBThe importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment researchClin Psychol Rev200929324325919269076

- KesslerRCThe costs of depressionPsychiatr Clin North Am201235111422370487

- GreenbergPEKesslerRCBirnbaumHGThe economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000?J Clin Psychiatry200364121465147514728109

- American Psychiatric AssociationPractice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder3rdArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Association2010 Available from: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=24158Accessed November 21, 2014

- MitchellJTrangleMDegnanBAdult Depression in Primary CareBloomington, MNInstitute for Clinical Systems Improvement2013[updated September 2013]. Available from: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdfAccessed April 5, 2014

- PattenSBKennedySHLamRWCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT)Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. I. Classification, burden and principles of managementJ Affect Disord2009117Suppl 1S5S1419674796

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5thWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- AniCBazarganMHindmanDDepression symptomatology and diagnosis: discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settingsBMC Fam Pract20089118173835

- The Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of DefenseClinical Practice Guideline for Management of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)Washington, DCDepartment of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense2009 Available from: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/mdd/mdd_full09_c.pdfAccessed November 15, 2014

- PaykelESPartial remission, residual symptoms, and relapse in depressionDialogues Clin Neurosci200810443143719170400

- EgedeLEMajor depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disabilityGen Hosp Psychiatry200729540941617888807

- RubioJMMarkowitzJCAlegriaAEpidemiology of chronic and nonchronic major depressive disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditionsDepress Anxiety201128862263121796739

- McClintockSMHusainMMWisniewskiSRResidual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medicationJ Clin Psychopharmacol201131218018621346613

- ZimmermanMMcGlincheyJBPosternakMAFriedmanMBoerescuDAttiullahNDiscordance between self-reported symptom severity and psychosocial functioning ratings in depressed outpatients: implications for how remission from depression should be definedPsychiatry Res2006141218519116499976

- RushAJKraemerHCSackeimHAACNP Task ForceReport by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorderNeuropsychopharmacology20063191841185316794566

- KupferDJLong-term treatment of depressionJ Clin Psychiatry199152Suppl28341903134

- SibilleEFrenchBBiological substrates underpinning diagnosis of major depressionInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20131681893190923672886

- ZimmermanMPosternakMAChelminskiIDefining remission on the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scaleJ Clin Psychiatry200465216316815003068

- ZimmermanMMartinezJAttiullahNFriedmanMTobaCBoerescuDASymptom differences between depressed outpatients who are in remission according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale who do and do not consider themselves to be in remissionJ Affect Disord20121421–3778122980402

- RushAJTrivediMHWisniewskiSRAcute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D reportAm J Psychiatry2006163111905191717074942

- WardenDRushAJTrivediMHFavaMWisniewskiSRThe STAR*D Project results: a comprehensive review of findingsCurr Psychiatry Rep20079644945918221624

- ZisookSGanadjianKMoutierCPratherRRaoSSequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): lessons learnedJ Clin Psychiatry20086971184118518687018

- JuddLLAkiskalHSMaserJDMajor depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapseJ Affect Disord1998502–3971089858069

- ConradiHJOrmelJde JongePSymptom profiles of DSM-IV-defined remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence of depression: the role of the core symptomsDepress Anxiety201229763864522581500

- ZimmermanMMcGlincheyJBPosternakMAFriedmanMAttiullahNBoerescuDHow should remission from depression be defined? The depressed patient’s perspectiveAm J Psychiatry2006163114815016390903

- FavaMGravesLMBenazziFA cross-sectional study of the prevalence of cognitive and physical symptoms during long-term antidepressant treatmentJ Clin Psychiatry200667111754175917196056

- LamRWMichalakEEBondDJTamEMAxlerAYathamLNWhich depressive symptoms and medication side effects are perceived by patients as interfering most with occupational functioning?Depress Res Treat2012201263020622611491

- BanerjeeSChatterjiPLahiriKIdentifying the mechanisms for workplace burden of psychiatric illnessMed Care201452211212024309665

- PaeCULimHKHanCFatigue as a core symptom of major depressive disorder: overview and the role of bupropionExpert Rev Neurother20077101251126317939764

- DemyttenaereKDe FruytJStahlSMThe many faces of fatigue in major depressive disorderInt J Neuropsychopharmacol2005819310515482632

- TritschlerLFeliceDColleRVortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorderExpert Rev Clin Pharmacol20147673174525166025

- SchultzEMaloneDAJrA practical approach to prescribing antidepressantsCleve Clin J Med2013801062563124085807

- ThaseMEChenDEdwardsJRuthAEfficacy of vilazodone on anxiety symptoms in patients with major depressive disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol201429635135624978955

- KurianBTGreerTLTrivediMHStrategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants: targeting residual symptomsExpert Rev Neurother20099797598419589048

- JeonHJFavaMMischoulonDPsychomotor symptoms and treatment outcomes of ziprasidone monotherapy in patients with major depressive disorder: a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sequential parallel comparison trialInt Clin Psychopharmacol201429633233824815673

- GreerTLSunderajanPGrannemannBDKurianBTTrivediMHDoes duloxetine improve cognitive function independently of its antidepressant effect in patients with major depressive disorder and subjective reports of cognitive dysfunction?Depress Res Treat2014201462786324563781

- McIntyreRSLophavenSOlsenCKA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vortioxetine on cognitive function in depressed adultsInt J Neuropsychopharmacol201417101557156724787143

- SinghABBousmanCANgCHByronKBerkMPsychomotor depressive symptoms may differentially respond to venlafaxineInt Clin Psychopharmacol201328312112623442739

- CooperJATuckerVLPapakostasGIResolution of sleepiness and fatigue: a comparison of bupropion and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in subjects with major depressive disorder achieving remission at doses approved in the European UnionJ Psychopharmacol201428211812424352716

- FavaMThaseMEDeBattistaCDoghramjiKAroraSHughesRJModafinil augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy in MDD partial responders with persistent fatigue and sleepinessAnn Clin Psychiatry200719315315917729016

- JacobsenPLMahableshwarkarARChenYChronesLClaytonAHRandomized, double-blind, head-to-head, flexible-dose study of vortioxetine vs escitalopram in sexual functioning in adults with well-controlled major depressive disorder experiencing treatment-emergent sexual dysfunctionPoster presented at: 29th CINP World Congress of NeuropsychopharmacologyJune 22–26, 2014Vancouver, Canada

- MontgomerySANielsenRZPoulsenLHHäggströmLA randomised, double-blind study in adults with major depressive disorder with an inadequate response to a single course of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor treatment switched to vortioxetine or agomelatineHum Psychopharmacol201429547048225087600

- WeizmanSGondaXDomePFaludiGPharmacogenetics of antidepressive drugs: a way towards personalized treatment of major depressive disorderNeuropsychopharmacol Hung20121428710122710850

- AzizRSteffensDCWhat are the causes of late-life depression?Psychiatr Clin North Am201336449751624229653

- NestlerEJEpigenetic mechanisms of depressionJAMA Psychiatry201471445445624499927

- PriceJLDrevetsWCNeural circuits underlying the pathophysiology of mood disordersTrends Cogn Sci2012161617122197477

- MoylanSMaesMWrayNRBerkMThe neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implicationsMol Psychiatry201318559560622525486

- StahlSMZhangLDamatarcaCGradyMBrain circuits determine destiny in depression: a novel approach to the psychopharmacology of wakefulness, fatigue, and executive dysfunction in major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200364Suppl 14617

- BlierPNeurotransmitter targeting in the treatment of depressionJ Clin Psychiatry201374Suppl 2192424191974

- KuhnMPopovicAPezawasLNeuroplasticity and memory formation in major depressive disorder: an imaging genetics perspective on serotonin and BDNFRestor Neurol Neurosci2014321254923603442

- KoolschijnPCvan HarenNELensvelt-MuldersGJHulshoff PolHEKahnRSBrain volume abnormalities in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studiesHum Brain Mapp200930113719373519441021

- McKinnonMCYucelKNazarovAMacQueenGMA meta-analysis examining clinical predictors of hippocampal volume in patients with major depressive disorderJ Psychiatry Neurosci2009341415419125212

- KennedySHEvansKRKrugerSChanges in regional brain glucose metabolism measured with positron emission tomography after paroxetine treatment of major depressionAm J Psychiatry2001158689990511384897

- GuoWLiuFYuMFunctional and anatomical brain deficits in drug-naive major depressive disorderProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry2014541624863419

- LumCTStahlSMOpportunities for reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase-A (RIMAs) in the treatment of depressionCNS Spectr201217310712023888494

- StahlSMStahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications4thNew York, NYCambridge University Press2013

- DrevetsWCPriceJLFureyMLBrain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depressionBrain Struct Funct20082131–29311818704495

- BlierPEl MansariMSerotonin and beyond: therapeutics for major depressionPhilos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci201336816152012053623440470

- HamonMBlierPMonoamine neurocircuitry in depression and strategies for new treatmentsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201345546323602950

- MoretCBrileyMThe importance of norepinephrine in depressionNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20117Suppl 191321750623

- DunlopBWNemeroffCBThe role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depressionArch Gen Psychiatry200764332733717339521

- O’LearyOFCryanJFChapter 4.13 – The behavioral genetics of serotonin: relevance to anxiety and depressionMullerCPJacobsBLHandbook of Behavioral Neuroscience21London, UKElsevier2010749789

- AmanTKShenRYHaj-DahmaneSD2-like dopamine receptors depolarize dorsal raphe serotonin neurons through the activation of nonselective cationic conductanceJ Pharmacol Exp Ther2007320137638517005915

- AdellABortolozziADiaz-MataixLSantanaNCeladaPArtigasFChapter 2.8 – Serotonin interactions with other transmitter systemsMullerCPJacobsBLHandbook of Behavioral Neuroscience21London, UKElsevier2010259276

- PehrsonALSanchezCSerotonergic modulation of glutamate neurotransmission as a strategy for treating depression and cognitive dysfunctionCNS Spectr201419212113323903233

- StahlSBrileyMUnderstanding pain in depressionHum Psychopharmacol200419Suppl 1S9S1315378669

- StahlSMLee-ZimmermanCCartwrightSMorrissetteDASerotonergic drugs for depression and beyondCurr Drug Targets201314557858523531115

- CiprianiAFurukawaTASalantiGComparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysisLancet2009373966574675819185342

- KennedySHA review of antidepressant therapy in primary care: current practices and future directionsPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2013152pii: PCC.12r01420

- OwensMJMorganWNPlottSJNemeroffCBNeurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolitesJ Pharmacol Exp Ther19972833130513229400006

- CirauloDABarnhillJGJaffeJHClinical pharmacokinetics of imipramine and desipramine in alcoholics and normal volunteersClin Pharmacol Ther19884355095183365915

- RenoirTSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involvedFront Pharmacol201344523596418

- JoelIBegleyAEMulsantBHIRL GREY Investigative TeamDynamic prediction of treatment response in late-life depressionAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201422216717623567441

- PanYJLiuSKYehLLFactors affecting early attrition and later treatment course of antidepressant treatment of depression in naturalistic settings: an 18-month nationwide population-based studyJ Psychiatr Res201347791692523566422

- GreerTLKurianBTTrivediMHDefining and measuring functional recovery from depressionCNS Drugs201024426728420297853

- AshtonAKJamersonBDWeinsteinWLWagonerCAntidepressant-related adverse effects impacting treatment compliance: results of a patient surveyCurr Ther Res Clin Exp20056629610624672116

- MaguraSRosenblumAFongCFactors associated with medication adherence among psychiatric outpatients at substance abuse riskOpen Addict J20114586423264842

- PrestonTCSheltonRCTreatment resistant depression: strategies for primary careCurr Psychiatry Rep201315737023712721

- PatkarAAPaeCUAtypical antipsychotic augmentation strategies in the context of guideline-based care for the treatment of major depressive disorderCNS Drugs201327Suppl 1S29S3723709359

- WrightBMEilandEH3rdLorenzRAugmentation with atypical antipsychotics for depression: a review of evidence-based support from the medical literaturePharmacotherapy201333334435923456734

- ChangTEJingYYeungASEffect of communicating depression severity on physician prescribing patterns: findings from the Clinical Outcomes in MEasurement-based Treatment (COMET) trialGen Hosp Psychiatry201234210511222264654

- ShaoLLiWXieQYinHTriple reuptake inhibitors: a patent review (2006–2012)Expert Opin Ther Pat201424213115424289044

- TranPSkolnickPCzoborPEfficacy and tolerability of the novel triple reuptake inhibitor amitifadine in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Psychiatr Res2012461647121925682

- SinghMSchwartzTLClinical utility of vilazodone for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder and theoretical implications for future clinical useNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2012812313022536068

- KatonaCLKatonaCPNew generation multi-modal antidepressants: focus on vortioxetine for major depressive disorderNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20141034935424570588

- GardierAMMalagiéITrillatACJacquotCArtigasFRole of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the mechanism of action of serotoninergic antidepressant drugs: recent findings from in vivo microdialysis studiesFundam Clin Pharmacol199610116278900496

- BétryCPehrsonALEtiévantAEbertBSánchezCHaddjeriNThe rapid recovery of 5-HT cell firing induced by the antidepressant vortioxetine involves 5-HT(3) receptor antagonismInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20131651115112723089374

- RichelsonEMulti-modality: a new approach for the treatment of major depressive disorderInt J Neuropsychopharmacol201316614331442

- Bang-AndersenBRuhlandTJorgensenMDiscovery of 1-[2-(2,4-dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine (Lu AA21004): a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorderJ Med Chem20115493206322121486038

- MørkAPehrsonABrennumLTPharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorderJ Pharmacol Exp Ther2012340366667522171087

- HedlundPBHuitron-ResendizSHenriksenSJSutcliffeJG5-HT7 receptor inhibition and inactivation induce antidepressantlike behavior and sleep patternBiol Psychiatry2005581083183716018977

- WeberSVolynetsVKanuriGBergheimIBischoffSCTreatment with the 5-HT3 antagonist tropisetron modulates glucose-induced obesity in miceInt J Obes (Lond)200933121339134719823183

- AlamMYJacobsenPLChenYSerenkoMMahableshwarkarARSafety, tolerability, and efficacy of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in major depressive disorder: results of an open-label, flexible-dose, 52-week extension studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol2014291364424169027

- CitromeLVortioxetine for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antidepressant – what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed?Int J Clin Pract2014681608224165478

- SchwartzTLSiddiquiUAStahlSMVilazodone: a brief pharmacological and clinical review of the novel serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitorTher Adv Psychopharmacol201113818723983930

- HammarASørensenLArdalGEnduring cognitive dysfunction in unipolar major depression: a test-retest study using the Stroop paradigmScand J Psychol201051430430820042028

- BauneBTMillerRMcAfooseJJohnsonMQuirkFMitchellDThe role of cognitive impairment in general functioning in major depressionPsychiatry Res20101762–318318920138370

- JaegerJBernsSUzelacSDavis-ConwaySNeurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorderPsychiatry Res20061451394817045658

- HasselbalchBJKnorrUKessingLVCognitive impairment in the remitted state of unipolar depressive disorder: a systematic reviewJ Affect Disord20111341–3203121163534

- HammarAArdalGCognitive functioning in major depression – a summaryFront Hum Neurosci200932619826496

- HasselbalchBJKnorrUHasselbalchSGGadeAKessingLVThe cumulative load of depressive illness is associated with cognitive function in the remitted state of unipolar depressive disorderEur Psychiatry201328634935522944336

- HarveyPOFossatiPPochonJBCognitive control and brain resources in major depression: an fMRI study using the n-back taskNeuroimage200526386086915955496

- MacDonaldAW3rdCohenJDStengerVACarterCSDissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive controlScience200028854721835183810846167

- Dell’OssoBCremaschiLSpagnolinGKetterTAAltamuraACAugmentative dopaminergic interventions for treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a focus on dopamine agonists and stimulantsJ Psychopathol201319327340

- MurroughJWWanLBIacovielloBNeurocognitive effects of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: association with antidepressant responsePsychopharmacology (Berl)20132313481488

- StrzeleckiDTabaszewskaABarszczZJózefowiczOKropiwnickiPRabe-JabłońskaJA 10-week memantine treatment in bipolar depression: a case report. Focus on depressive symptomatology, cognitive parameters and quality of lifePsychiatry Investig2013104421424

- KatonaCHansenTOlsenCKA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol201227421522322572889

- IversonGLLamRWRapid screening for perceived cognitive impairment in major depressive disorderAnn Clin Psychiatry201325213514023638444

- FerentinosPPKontaxakisVPHavaki-KontaxakiBJDikeosDGPapadimitriouGNFatigue and somatic anxiety in patients with major depressionPsychiatriki200920431231822218232

- FavaMBallSNelsonJCClinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorderDepress Anxiety201431325025724115209

- SoyuerFŞenolVFunctional outcome and depression in the elderly with or without fatigueArch Gerontol Geriatr2011532e164e16720850877

- TargumSDFavaMFatigue as a residual symptom of depressionInnov Clin Neurosci20118104043

- MacHaleSMLawŕieSMCavanaghJTCerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depressionBr J Psychiatry200017655055610974961

- PapakostasGINuttDJHallettLATuckerVLKrishenAFavaMResolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsBiol Psychiatry200660121350135516934768

- McClungCAHow might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways…Biol Psychiatry201374424224923558300

- GrandnerMADrummondSPWho are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationshipSleep Med Rev200711534136017625932

- LaiYCHuangMCChenHCFamiliality and clinical outcomes of sleep disturbances in major depressive and bipolar disordersJ Psychosom Res2014761616724360143

- OswaldIAdamKEffects of paroxetine on human sleepBr J Clin Pharmacol198622197992943309

- Salin-PascualRJGalicia-PoloLDrucker-ColinRSleep changes after 4 consecutive days of venlafaxine administration in normal volunteersJ Clin Psychiatry19975883483509515972

- SaperCBChouTCScammellTEThe sleep switch: hypothalamic control of sleep and wakefulnessTrends Neurosci2001241272673111718878

- Santos MoraesWABurkePRCoutinhoPLSedative antidepressants and insomniaRev Bras Psiquiatr2011331919521537726

- FagioliniAComandiniACatena Dell’OssoMKasperSRediscovering trazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorderCNS Drugs201226121033104923192413

- WeberJSiddiquiMAWagstaffAJMcCormackPLLow-dose doxepin: in the treatment of insomniaCNS Drugs201024871372020658801

- MacleanLAhmedaniBKSertraline and low-dose doxepin treatment in severe agitated-anxious depression with significant gastrointestinal complaints: two case reportsPrim Care Companion CNS Disord2011134pii: PCC.12r01420

- BeckerPMSattarMTreatment of sleep dysfunction and psychiatric disordersCurr Treat Options Neurol200911534935719744401

- De BerardisDMariniSFornaroMThe melatonergic system in mood and anxiety disorders and the role of agomelatine: implications for clinical practiceInt J Mol Sci2013146124581248323765220

- KennedySHCyriacAA dimensional approach to measuring antidepressant response: implications for agomelatinePsychology2012310864869

- CardinaliDPSrinivasanVBrzezinskiABrownGMMelatonin and its analogs in insomnia and depressionJ Pineal Res201252436537521951153

- LaudonMFrydman-MaromATherapeutic effects of melatonin receptor agonists on sleep and comorbid disordersInt J Mol Sci2014159159241595025207602