Abstract

Poststroke depression (PSD) in elderly patients has been considered the most common neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke up to 6–24 months after stroke onset. When depression appears within days after stroke onset, it is likely to remit, whereas depression at 3 months is likely to be sustained for 1 year. One of the major problems posed by elderly stroke patients is how to identify and optimally manage PSD. This review provides insight to identification and management of depression in elderly stroke patients. Depression following stroke is less likely to include dysphoria and more likely characterized by vegetative signs and symptoms compared with other forms of late-life depression, and clinicians should rely more on nonsomatic symptoms rather than somatic symptoms. Evaluation and diagnosis of depression among elderly stroke patients are more complex due to vague symptoms of depression, overlapping signs and symptoms of stroke and depression, lack of properly trained health care personnel, and insufficient assessment tools for proper diagnosis. Major goals of treatment are to reduce depressive symptoms, improve mood and quality of life, and reduce the risk of medical complications including relapse. Antidepressants (ADs) are generally not indicated in mild forms because the balance of benefit and risk is not satisfactory in elderly stroke patients. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the first choice of PSD treatment in elderly patients due to their lower potential for drug interaction and side effects, which are more common with tricyclic ADs. Recently, stimulant medications have emerged as promising new therapeutic interventions for PSD and are now the subject of rigorous clinical trials. Cognitive behavioral therapy can also be useful, and electroconvulsive therapy is available for patients with severe refractory PSD.

Keywords:

Scope of the problem: aging, stroke, and poststroke depression

Incidence of stroke increases sharply with age,Citation1 a fact that each successive decade above 55 years leads to a doubling of stroke incidence.Citation2 According to a recent population-based stroke study in Europe, 70.2% of stroke patients were older than 65 years, and the median age was 73 years (interquartile range, 62–81).Citation3 The combined impact of increased life expectancy and medical management advancements has resulted in a larger number of elderly persons surviving stroke.Citation4

The physical and psychological sequelae caused by stroke can be devastating.Citation5 Poststroke depression (PSD) is one of the unresolved issues in recovery and rehabilitation of the stroke patients. It has been considered the most common neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke.Citation6 Depression may either directly or indirectly lead to more significant impairments in daily activities, which require more careful services and institutionalization of stroke patients.Citation7–Citation9 The risk of fatality is higher in stroke patients with depression compared with nondepressed stroke patients.Citation10 Deteriorated cognitive function and increased medical complication rates among patients with PSD adversely influence the speed of recovery and the level of residual function following rehabilitation.Citation11–Citation12 Other consequences of PSD include higher health care costs, diminished social abilities, and an increased risk of vascular-related events and death.Citation13,Citation14

One of the major problems posed by elderly stroke patients is how to identify and optimally manage PSD, which is more common in elderly stroke patients than younger stroke patients. The aim of this review is to provide insight to symptoms, identification, diagnosis, and management of depression in elderly stroke patients.

Search strategy and selection criteria

References for this review were recognized through search in PubMed for potentially relevant articles with the search terms of “depression” and “depressive disorder” in combination with “elderly,” “older,” “stroke,” “cerebrovascular,” and “ischemia.” Preference was given to articles published between January 1981 and January 2010. Only articles published in English were reviewed. The final citation list was selected based on relevance to PSD in elderly patients. Our search strategy identified 2,547 nonduplicated references of which 274 articles were considered relevant. After reviewing abstracts, 150 articles were examined in detail, yielding 67 articles to match the eligibility criteria.

Epidemiology of PSD

Depression is a common consequence of stroke up to 2–3 years after stroke onset.Citation15 Prevalence rates of PSD vary from 6% to 79%.Citation16,Citation17 These rates show considerable variation between studies and amongst different populations. PSD rates depend on the setting in which patients are examined, demonstrating greater rates among hospital inpatient-based locations (acute stroke units, general hospital wards, or rehabilitation centers) than community-based settings.Citation5,Citation18 Differences in definitions of PSD and patient selection criteria (including prior patient history of depression) combined with disparity among evaluation instruments resulted in large variability between studies, making results difficult to interpret.Citation17,Citation19 In the acute period (<1 month after stroke), the frequency of depressive disorders was found to be 30%, 33%, and 36% in rehabilitation, community, and hospitalbased settings, respectively.Citation20 Approximately 1–6 months after stroke, the frequency of depressive disorders was somewhat higher in rehabilitation settings (36%) compared with community- and hospital-based settings.Citation20 Most studies examined the risk of depression in younger patient populations, whereas only few studies investigated that in elderly stroke patients. Few studies relate the frequency of PSD adjusted for age or sex.Citation21,Citation22 The prevalence of depressive disorders in those older than 55 years (when stroke commonly occurs) has been estimated to be 18% in women and 11% in men.Citation23 Even this figure may be an underestimation due to exclusion of patients with impaired communication, such as patients with aphasia (including 25% of the stroke patients) or patients with dementia.Citation24 Among a population of elderly residents in the United States, a community survey on the prevalence of depression showed 42.9% for men and 64.1% for women, generally a high rate of stroke survivors.Citation25 Linden et alCitation26 showed that the frequency of depressive disorders in a consecutive series of hospitalized elderly stroke patients 20 months after stroke onset was 34% in the stroke patients and 13% in controls. Patients recruited for this study were selected from hospitalized stroke patients, who were more severely affected in general. Because most stroke patients in Sweden are treated in hospitals (even those with mild symptoms), the authors considered that their sample reasonably reflects the total elderly stroke population.Citation26

Pathophysiology of PSD

The primary biological mechanism is proposed to be the cause of PSD, whereby ischemic insults directly affect neural circuits involved in mood regulation.Citation27,Citation28 An injury to the brain’s catecholamine pathway reduces the release of neurotransmitters with a likely depression as a result. A depletion in cortical biogenic amines is found after a disruption of frontal-subcortical circuits after stroke.Citation29 However, there are also arguments for a psychological basis of PSD put forth by researchers. This relates to the similarity of symptoms and treatment response profiles between PSD and functional depression. Carson et alCitation30 performed a meta-analysis in which they noted that the risk of depression did not relate to the location of the cerebral lesion. However, most PSD appears to be multifactorial in origin. However, some stroke survivors may have a PSD purely biological in origin, and some purely psychological.

Clinical manifestations of PSD

PSD occurring within the first 3 months of stroke is classified as “early” and is defined as “late” when the symptoms appear later.Citation31 Early PSD patients have more depressive somatic signs compared with psychological symptomsCitation32 and more frequently show early symptoms of melancholy, vegetative signs, and psychological disturbances.Citation33 PSD may appear shortly after stroke but usually develops several months after a cerebrovascular event.Citation18 Peak incidence and greatest severity of depression commonly occur between 6 months and 2 years after stroke.Citation34 Robinson et alCitation34 found major depression in assessments immediately after a stroke in almost one-third of patients and noted that 60% of those patients still were depressed 1 year later. Depressive symptoms at any level of severity can be recognized in 18%–30% of patients during 3–5 years after stroke.Citation35–Citation37

Depression presents differently among patients with neurological syndromes.Citation24 Depression following stroke, especially stroke with right hemisphere damage, is less likely to include dysphoria and more likely characterized by vegetative signs and symptoms compared with other forms of late-life depression.Citation38 In 2004, MastCitation39 showed that stroke patients were more likely to exhibit social withdrawal and were less likely to exhibit agitation compared with geriatric depression accompanying other medical illnesses, although there were no differences in depressed mood or energy between them. Robinson and his coworkersCitation40,Citation41 suggested that somatic symptoms are more common among stroke patients when depressed mood is present. In this case, clinicians are more sensitive to similarities between somatic features, commonly seen in older medical patients, and clinical features typical of depression.Citation42 For the most accurate diagnoses, clinicians should rely more on nonsomatic symptoms rather than somatic symptoms.Citation43 Some symptoms are common to both stroke and depression, such as sleep disturbances, concentration difficulties, and reduced appetite, which might cause an overestimation of depression in stroke patients.Citation44 In older people with cognitive impairments due to aging and degenerative disorders, additional cognitive impairments caused by depression can be more troublesome.Citation45 About 2%–3% of patients without stroke show “masked” depression (depressive symptoms without an associated depressed mood) with manifestations of biological rhythm impairment (like sleeplessness or hypersomnia) and somatization, particularly autonomic vascular dystonia, vertigo, or various dysalgic phenomena.Citation46

Depressive disorders in older vs younger adults

Clinically, there are differences between depressed younger and older people. When comparing elderly adult depression vs young adult depression, there is a dynamic increase in the level of somatic symptoms, including loss or lack of interests and other affective symptoms, such as dysphoria, worthlessness, or guilt.Citation24 Somatic symptoms often obscure depression in older people either because of the somatic nature of the disorder or because of the escalation of symptoms of an existing physical illnessCitation47 (). Older patients seldom have evident signs of low mood, so they do not meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (DSM-IV) criteria for major depression.Citation47 It has been shown that older adults focus more on positive and emotionally meaningful experiences, which provides better emotion regulation with advancing age.Citation48 In contrast to younger depressed patients, elderly patients often hide their mood with the mentality that decreased life fulfillment is a normal consequence of aging and disease (stroke).Citation49 Among depressed older adults, subjective complaints of poor memory and lack of concentration are common, whereas symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbance, psychomotor retardation, and hopelessness about the future are more common among depressed younger adults.Citation50

Table 1 Differences in clinical picture between younger and elderly patients with depressive disordersCitation47

Factors contributing to the risk of PSD

Several factors that impact the risk of PSD development have been identified. Social isolation, living alone, physical functional impairments, or a history of depression (or other psychiatric disorder) are identified as predictive risk factors for PSD.Citation51–Citation53 However, not all studies confirm the association between PSD and social factors, such as poststroke social isolation and living alone.Citation53 Some symptoms associated with PSD are the same as the risk factors, such as reduced social activity, failure to return to work, and poor participation in processes of rehabilitation.Citation54

Gender has been found to be mildly associated with PSD. Some authors have reported that PSD is twice as common in women as in men,Citation55 whereas others found that older, physically disabled men with inadequate social support were more likely to experience PSD.Citation56 Major depression in women has been associated with higher education level, prior psychiatric diagnoses, and cognitive impairments.Citation56 Women mostly have early PSD, whereas men were more likely to have late PSD.Citation15

There is no clear relationship between the severity of stroke and the occurrence of PSD.Citation57 Research has shown that 50% of those who have experienced a stroke 3 months ago are more plausible to be depressed yet another year. Another difference between those patients who are shown to be depressed within days after stroke is the likelihood to show remission.Citation58 Some investigators found depression to be more likely among persons with large lesionsCitation59 and severe stroke injury scores,Citation60 but other studies have not confirmed this.Citation61 Questions have arisen whether the site of infarct can influence the PSD development.Citation62 In a meta-analysis of 35 studies conducted by Carson et alCitation30 no data conclusively supported an association between intrahemispheric location and the risk of depression. Desmond et alCitation42 did not recognize an association between lesion location and depression in older stoke patients. However, other studies found an increased risk of PSD with left-brain lesions.Citation63 Linden et alCitation26 found no association between the predominant side of symptoms at the time of the stroke onset and depressive syndromes. Likewise, there is a chance that lesion location is related to depression in the acute phase of stroke.Citation26 This inconsistency of results might be related to study design, assessors, and assessment tools for diagnosing PSD. In most studies that showed a relationship between PSD and right-hemisphere lesions, patients with left-hemisphere damage were excluded due to the language problem caused by stroke. In contrast, in studies showing a moderate relationship between left-hemisphere lesion and PSD, stroke patients with language dysfunction were not excluded.

According to a recent systematic review by Hackett and Anderson,Citation64 some consistent identification has been positively associated with depression following stroke, such as stroke severity, physical disability, and cognitive impairment.

Diagnosis of PSD

Diagnosis of PSD in stroke survivors may be difficult due to the presence of other symptoms such as common cognitive impairments, including aphasia, agnosia, apraxia, and memory problems.Citation65 On the other hand, many methods of diagnosing depression rely on somatic symptoms that, in turn, may complicate the diagnosis of PSD.Citation46 In case of the presence of depression and somatic diseases, diagnosis and treatment of PSD are even more complicated and have adverse impact on the clinical presentations and prognosis of the underlying disease.Citation46 However, evaluation of depression among elderly stroke patients is more complex due to influence of somatic conditions, such as cognitive, sensory, and language impairments. Also certain challenging factors might overlap typical symptoms of depression from normal signs of aging and stroke disease, including thoughts regarding death, reduced sleep, fatigue, and loss of libido.

In brief, following factors contribute to the difficulty of diagnosing PSD: (1) overlapping signs and symptoms of stroke and depression, which are indistinguishable to each other, to the patient and providers, (2) lack of proper training in mental health care professionals to recognize which symptoms are more related to stroke than depression, and (3) medical care providers usually have limited knowledge about the differences between depression and “typical” signs of aging and stroke.Citation57 Therefore, clinicians should define a set of valid criteria for diagnosis of PSD.Citation66 Some scientists believe that symptom profile of PSD is similar to that of nonstroke depression; therefore, diagnosis criteria should be the same for both,Citation40 but it is not commonly agreed on among all clinicians and researchers.Citation67

Screening and evaluation of PSD

Unfortunately, there are not many researches and data regarding diagnostic criteria of PSD, but 2 reports suggest that using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) has been reasonable in the elderly patients.Citation68 This 15-item short form questionnaire has been studied widely and is validated in a number of patients, and it is easy to administer.Citation69 The GDS is most useful in diagnosis of depression among patients who are in higher functioning levels and have mild cognitive impairment.Citation70 Several authors have suggested that this scale instead of other scales, like the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), to be most satisfactory screening instrument for PSD.Citation68,Citation71,Citation72 Neurologists can easily try GDS on a wide range of patients.Citation73 GDS has been used to identify PSD in Caucasian patients in acute inpatient and rehabilitation conditions.Citation74 Also GDS has performed relatively well as a screening method in Caucasian patients with strokeCitation72 ().

Table 2 Characteristics of Geriatric Depression Scale (15-item)Citation18,Citation24,Citation70,Citation75,Citation76

In a recent clinical trial, Healey et al screened 49 elderly stroke patients for depression.Citation77 They compared 3 depression scales: Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards (BASDEC), the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen (BDI-FS), and the HADS. They showed that BASDEC and BDI-FS have adequate internal consistency. The BASDEC compared with BDI-FS had some benefits in criterion validity in elderly stroke patients. Regarding the criterion at the examined cutoffs, the BDI-FS and HADS were less accurate in relation. The BASDEC was developed to evaluate depression in elderly patients in a hospital ward environment.Citation78 It is a 19-question measure that tests depression symptoms, each question on a separate card (8.2 cm × 10.4 cm), and the maximum score is 21. Higher scores of BASDEC indicate worse function. It has shown a very good sensitivity (>0.80), specificity (>0.90), and accuracy in predicting clinical results of medically ill elderly patients.Citation79 Both GDS and BASDEC are not time-consuming to administer, and they are relatively free of somatic symptoms.Citation80 Adshead et alCitation78 showed that agreement between the 2 scales was high. However, McCrea et alCitation80 found that BASDEC was easier to administer. In a systematic review, Hackett and AndersonCitation64 recommended that the gold standard method for diagnosis PSD is using a semistructured psychiatric interview, which meets all the standards needed for a specific diagnostic criterion (such as DSM criteria or International Classification of Diseases). According to the current diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV-TR, 5 or more symptoms must be present at least over a 2-week period for receiving a major depression diagnosisCitation81 (). Less severe forms of depressive disorder, which might not meet criteria for major depression, have been diagnosed as either minor depression or dysthymic disorder. This diagnosis requires at least the presence of 1 major criterion symptom and a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 4 of the specific symptoms in a 2-year course of chronic depressive manifestations.Citation57

Table 3 Diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV Citation81,Citation82

Management strategies of PSD

There is no reason to refuse any kind of treatment to elderly patients with PSD based on age alone, as many older individuals had a high baseline life quality and expectancy for many more years. A key problem, which can be mentioned as a factor leading to undertreatment of PSD, is that both the patient and the doctor often do not accept this condition as a treatable illness.Citation83 A more worrying problem is that when evaluating an older patient, the physician concentrates on other aspects of the patient and dismisses the depressive symptoms. Unfortunately, it has been estimated that 80% of the PSD patients might be missed by nonpsychiatric clinicians.Citation84

Meanwhile, early diagnosis of PSD is extremely important to make an efficient treatment plan for the patient. The importance of an early recognition and diagnosis of PSD is widely agreed upon to improve functional and psychosocial outcomes.Citation85 All treatments must be modified to individual needs based on patient’s needs, including cost, accessibility, and availability of treatments.Citation64 Effective treatment will generally include the participation of the family and other support networks.Citation64 In all circumstances, it is recommended that the treating clinician supervise a person presenting with depression at least weekly for the first 6 weeks to evaluate mood changes, suicidal thinking, physical safety, the person’s social life, and adverse effects of any drugs that have been prescribed.Citation64

Major goals of such a treatment include reducing depressive symptoms, improving mood and quality of life, using health care resources appropriately, and reducing the risks of medical complications.Citation86 The management of PSD includes pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy,Citation6 and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), used especially in those with severe depressive illness.

Pharmacological treatment

Despite more than 100 years of studies of PSD, there are still several challenges regarding PSD pharmacotherapy, including determining its effectiveness.Citation87 Pharmacotherapy may be particularly complicated in elderly PSD individuals, who often have high rates of medical comorbidity, concomitant polypharmacy, and more vulnerability to the adverse effects of antidepressants (ADs). It is important that the AD used should not only be effective in controlling mood disorders but also lack adverse effects on cognitive functions, which is particularly relevant to patients who have had strokes and more or less cognitive impairmentsCitation46 (). There are many variables involved in pharmacotherapy of elderly patients, including pharmacokinetic changes associated with aging, drug interactions with other medications, preexisting illnesses, and adverse effects of the drugs on the elderly due to their increased vulnerability.

Table 4 Criteria for ideal antidepressant choice in elderly patients

AD drugs

ADs can be effective in most moderate and severe depressive disorders but are generally not indicated in mild forms because the balance of benefit and risk is not satisfactory in elderly stroke patients. Even when depression is properly diagnosed in elderly patients, they still may not receive the medication they require,Citation88 and because of possible severe side effects of ADs in elderly patients, more often the clinicians avoid prescribing such medications to them.Citation88 Unfortunately, even when AD treatment is administered for an old patient, it is mostly in inadequate doses and for shorter durations than recommended.Citation89

Until now, there is no evidence for using pharmacological or psychotherapeutic methods for PSD prevention after stroke,Citation85,Citation90,Citation91 and a Cochrane meta-analysis of PSD treatment trials confirmed that there was no sufficient indication to suggest drug treatment specifically for the remission of PSD or its prevention.Citation85,Citation91 In a recent systematic review of trials on pharmacological therapy in PSD, Hackett et alCitation92 reported that although ADs were able to reduce mood disorder symptoms, they had no clear effect on prevention or remission of depressive illness after stroke. However, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study performed by Robinson et alCitation93 showed that escitalopram as preventive active drug, compared with placebo over the first year after stroke, decreased the frequency of PSD. However, the overall benefit when potential side effects and complications of active treatment are considered is still unclear.

The choice of ADs

For the choice of ADs in PSD, the comparative information is quite limited, and none of them is specific to PSD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first choice of PSD treatment in elderly patients due to their lower potential for drug interaction and side effects. Drug group, efficacy, and side effects of different medications are presented in and .

Table 5 Antidepressants mostly used in late-life depression

Table 6 Comparison of SSRIs with TCAsCitation24,Citation86,Citation91

Stimulant medications

For many years, stimulant medications have been employed in stroke rehabilitation and in PSD, but large randomized clinical trials are still lacking. During 1950s, methylphenidate (MPH) was reported to be an effective treatment for geriatric depression,Citation94 and case reports of Kaufman and his coworkersCitation80 also suggested the efficacy of MPH for PSD. Lingam et al conducted a retrospective study on the efficacy and side effects of MPH by systematically reviewing hospital charts of 25 depressed stroke patients, who were treated with MPH.Citation95 The result of this study suggested a high degree of efficacy (80% improvement of depressive symptom) and a relatively low incidence of side effects. In a retrospective study, Lazarus et alCitation96 reviewed hospital charts of older adults with stroke and major depression. Among studied cases, 30 were treated with nortriptyline and 28 with MPH. Symptoms of depression resolved in 53% of MPH-treated patients and 43% of nortriptyline-treated patients, which showed no significant difference.Citation96 However, a more significant difference was observed in response time. In MPH-treated patients, the mean response time to peak effect was 2.4 days compared with 27 days for nortriptyline-treated patients. Also, side effects were reported in 14% of MPH-treated patients and 30% of nortriptyline-treated patients, including delirium, requiring termination of nortriptyline therapy in 2 patients.Citation96 They also prospectively studied MPH administration for elderly stroke patients (mean age, 73 years),Citation97 which was started at a dose of 2.5–5 mg in the morning and at noon, which was slowly increased to 40 mg/d. Mean dosage used at about the 10th day was 17 mg/d. Interestingly, over 3 weeks of therapy, 80% of patients showed a full or partial response based on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. MPH was shown to be a safe and efficient therapy for elderly patients with PSD. Fast onset of action (usually within 3–10 days) and relatively few adverse effects of MPH may offer significant benefits over tricyclic ADs (TCAs), whose onset of action needs 2–4 weeks.Citation97 It can be concluded that specifically in conditions where patients’ active participation in the recovery process is essential and issues like limitations in insurance coverage and subsequently shorter hospital stays, prescribing MPH would be best option.

In another prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Grade et alCitation98 compared MPH and placebo among PSD patients. MPH was started at 5 mg and increased gradually to 30 mg (15 mg at 8:00 am and 15 mg at 12:00 noon). After a 3-week treatment period with MPH (or placebo) in conjunction with physical therapy, the results confirmed that MPH is a safe and efficient adjunct therapy in the rehabilitation of acute stroke patients. MPH therapy has many benefits, including mood elevation, better motor functioning, and the ability to conduct regular daily activities without any considerable side effects.

Course of drug treatment

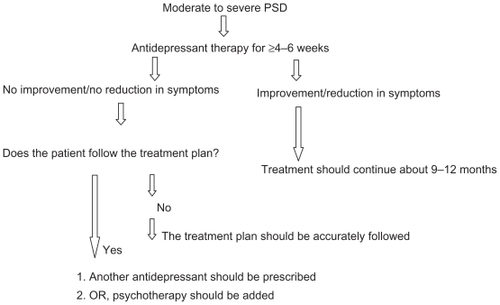

Based on the guidelines of the American College of Physicians, antidepressive drugs should be continued at least for 4 months after initial recovery and should be changed if no response has been seen after 6 weeks.Citation99 AD treatment also should be continued for a minimum of 6 months in those patients with response to therapy. Later on, AD treatment can be slowly withdrawn, or in case of relapse, it can be continued for a longer duration.Citation65,Citation100 ADs should also be prescribed to patients with moderate to severe depression even before psychological interventions, and they should be continued for at least 4–6 weeks, at the doses recommended by the manufacturerCitation64 ().

Nonpharmacological management

Several reasons have been suggested in favor of nonpharmacological management, including the possibility of complications, which may occur when treating elderly depressed individuals due to adverse effects of the ADs, their inability to modify adverse environmental stressors, and a lack of social support factors, which often respond to a psychological approach.Citation18 Nonpharmacological interventions in PSD have included psychotherapy, ECT, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Psychological interventions are the preferred method of treatment for mild mood disordersCitation64 and are reserved for those in whom ADs are either inappropriate or not tolerated.Citation101 In most psychological treatments, a behavioral activation component is often involved, which treats the problem of activity limitation. Although some of these approaches mainly focus on the meaningfulness of the activity during the treatment, the possibility of targeting depression and intensifying and maintaining cognitions has also been practiced.Citation24 Psychological treatments include behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), problem-solving therapy, and life review therapy.Citation102 Also, Watkins et alCitation103 have recently shown that motivational interviewing is effective, leading to improved patients’ mood 3 months after stroke. Unfortunately, there are some drawbacks for these interventions, including their costs in terms of staff time and expertise and their slow and delayed response, which requires several weeks before showing any clinical improvements.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT has a very strong and positive effect on patients because it not only improves and builds confidence but also enhances the daily lifestyle of the patients through a range of activities. The treatment requires qualified health professionals to constantly evaluate the participants, making it easier to satisfy the diverse needs of the individuals. By this method, CBT is designed to challenge dysfunctional thoughts or beliefs that are associated with low mood and to collaboratively establish more functional thoughts or beliefs.Citation66 However, patients with cognitive impairment and/or aphasia are not suited to this treatment form.

CBT is based on giving insights towards psychoeducation, collaborative empiricism, active problem solving, assessing the nature and quality of supports, and improvement of the adaptation to the new lifestyle after a stroke.Citation104 Patients will find out how their thoughts may contribute to affective symptoms and feelings and how they can transform them.Citation105

For individuals diagnosed with a range of chronic disabling physical conditions, such as stroke and PSD, a 12-week course of CBT, as advised and conducted by Kemp et al was shown effective.Citation106

In general, approximately 6–8 regular sessions should be provided to patients over a period of 10–12 weeks, with most people experiencing an improvement in mood and/or a reduction in symptoms after 2 months of therapy. Response to therapy should be reviewed after 8 sessions. A therapy extension period of 6 months is considered necessary for a person who has multiple issues or severe comorbidity.Citation64 Psychotherapy should be combined with ADs to reduce residual symptoms and the risk of relapse in patients with severe depressionCitation107 and in those with moderate or severe depression who refuse to take ADs.Citation107 However, in a randomized controlled trial, Lincoln et alCitation108 showed that CBT in the treatment of PSD was not effective, and they suggested that further evaluation with large sample size is needed to more clearly assess the role of CBT in PSD. Also in a Cochrane review for depression intervention after stroke, it was shown that psychotherapeutic intervention for PSD has failed to provide evidence for effectiveness.Citation85

Electroconvulsive therapy

ECT should only be used to achieve rapid and short-term improvement of severe depressive symptoms after other treatments have proven ineffective. It is not recommended as a primary or maintenance therapy for PSD.Citation109 It is used more often in older adults compared with any other age group. Its primary indication is severe depressive illness or when a disorder (or its symptoms) is considered potentially life threatening.Citation64 A retrospective review of patients treated with ECT showed improvement in 95% of PSD.Citation110 Approximately 50% of patients had a prestroke history of major depression or alcoholism, and 85% already had received antidepressive medications to which they did not respond or were intolerant. According to the results obtained from 2 small samples of 14 and 20 PSD patients,Citation111,Citation112 approximately 40% of patients had a relapse of depressive symptoms after ECT in the short termCitation111 and 20% developed medical complications.Citation112 ECT is therefore not a recommended therapy for depressed stroke patients, and adverse events such as cardiac complications, memory loss, and delirium suggest caution with the use of ECT for older PSD patients.Citation64

Key issues

Monitoring and assessing for depression are highly recommended after stroke, particularly for those having risk factors associated with PSD development, and delivering proper management, in the case of confirmed diagnosis.

To improve recovery, facilitate rehabilitation, and decrease mortality, early recognition of PSD is required.

Some factors, including older age, female sex, stroke severity, and functional dependence, further contribute to PSD development.

There are a number of factors that make treatment more complicated in the elderly patient, including the high rate of comorbid disorders and often an increased sensitivity to possible side effects of medications.

Evidence does not show any association between severity of PSD and side effect of stroke lesion.

Frequency of depressive disorders in elderly patients is higher than the frequency of depressive disorders in age- and sex-matched controls.

Despite serious mood disorders occurring after stroke, no reliable evidence-based clinical management method has existed so far.

Treatment might be more demanding in elderly patients because of factors like the high rate of comorbid disorders and often an increased sensitivity to the side effects of medication.

SSRIs have been found to be superior to TCAs in treatment of depression in old age.

MPH appears to be a safe and effective treatment for elderly stroke patients with PSD.

More advanced standard screening and diagnostic tools and more effective and safer treatments will help not only to treat this patient population effectively but also to decrease health care burden and costs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HazzardWEttingerWJrAging and atherosclerosis: changing considerations in cardiovascular disease prevention as the barrier to immortality is approached in old ageAm J Geriatr Cardiol199544163611416341

- SaccoRAdamsRAlbersGAlbertsMBenaventeOFurieKAmerican Heart Association; American Stroke Association Council on Stroke; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Academy of NeurologyGuidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guidelineStroke200637257761716432246

- The European Registers of Stroke (EROS) InvestigatorsIncidence of stroke in Europe at the beginning of the 21st centuryStroke20094051557156319325154

- SanossianNOvbiageleBPrevention and management of stroke in very elderly patientsLancet Neurol20098111031104119800847

- PoynterBShumanMDiaz-GranadosNKapralMGraceSStewartDSex differences in the prevalence of post-stroke depression: a systematic reviewPsychosomatics200950656356919996226

- RobinsonRGNeuropsychiatric consequences of strokeAnnu Rev Med19974812172299046957

- PaolucciSAntonucciGPratesiLTraballesiMGrassoMLubichSPoststroke depression and its role in rehabilitation of inpatientsArch Phys Med Rehabil199980998599010488996

- van de WegFKuikDLankhorstGPost-stroke depression and functional outcome: a cohort study investigating the influence of depression on functional recovery from strokeClin Rehabil199913326827210392654

- PohjasvaaraTVatajaRLeppävuoriAKasteMErkinjunttiTDepression is an independent predictor of poor long-term functional outcome post-strokeEur J Neurol20018431531911422427

- WadeDLegh-SmithJHewerRDepressed mood after stroke. A community study of its frequencyBr J Psychiatry198715122002053690109

- ParikhREdenDPriceTRobinsonRThe sensitivity and specificity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in screening for post-stroke depressionInt J Psychiatry Med19881821691813170080

- StarksteinSRobinsonRPriceTComparison of patients with and without poststroke major depression matched for size and location of lesionArch Gen Psychiatry19884532472523341879

- EnsinckKSchuurmanAvan den AkkerMIs there an increased risk of dying after depression?Am J Epidemiol2002156111043104812446261

- GlassmanAShapiroPDepression and the course of coronary artery diseaseAm J Psychiatry199815514119433332

- BergAPalomakiHLehtihalmesMLonnqvistJKasteMPoststroke depression: an 18-month follow-upStroke200334113814312511765

- WhyteEMulsantBVanderbuiltJDodgeHGanguliMDepression after stroke: a prospective epidemiological studyJ Am Soc Geriatr Dent2004525774778

- ProvincialiLCocciaMPost-stroke and vascular depression: a critical reviewNeurol Sci200222641742811976972

- GaeteJBogousslavskyJPost-stroke depressionExpert Rev Neurother200881759218088202

- RaoRCerebrovascular disease and late life depression: an age old association revisitedInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200015541943310822241

- HackettMYapaCParagVAndersonCFrequency of depression after stroke. A systematic review of observational studiesStroke20053661330134015879342

- HouseADennisMMogridgeLWarlowCHawtonKJonesLMood disorders in the year after first strokeBr J Psychiatry1991158183922015456

- AndersenGVestergaardKRiisJLauritzenLIncidence of post-stroke depression during the first year in a large unselected stroke population determined using a valid standardized rating scaleActa Psychiatr Scand20079031901957810342

- SonnenbergCBeekmanADeegDTilburgWSex differences in late-life depressionActa Psychiatr Scand200110142869210782548

- FiskeAWetherellJGatzMDepression in older adultsAnnu Rev Clin Psychol2009536338919327033

- MurrellSHimmelfarbSWrightKPrevalence of depression and its correlates in older adultsAm J Epidemiol198311721731856829547

- LindenTBlomstrandCSkoogIDepressive disorders after 20 months in elderly stroke patients: a case-control studyStroke20073861860186317431211

- RobinsonRVascular depression and poststroke depression: where do we go from here?Am J Geriatr Psychiatry2005132858715703316

- RobinsonRStarrLLipseyJRaoKPriceTA two-year longitudinal study of post-stroke mood disorders: dynamic changes in associated variables over the first six months of follow-upStroke19841535105176729881

- DieguezSStaubFBruggimannLBogousslavskyJIs poststroke depression a vascular depressionJ Neurol Sci2004226125358

- CarsonAMacHaleSAllenKDepression after stroke and lesion location: a systematic reviewLancet2000356922412212610963248

- Carod-ArtalFAre mood disorders a stroke risk factor?Stroke20073811317138953

- BebloTDriessenMNo melancholia in poststroke depression? A phenomenologic comparison of primary and poststroke depressionJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol2002151444911936243

- TatenoAKimuraMRobinsonRPhenomenological characteristics of poststroke depression: early-versus late-onsetAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200210557558212213692

- RobinsonRBolducPPriceTTwo-year longitudinal study of poststroke mood disorders: diagnosis and outcome at one and two yearsStroke19871858378433629640

- WilkinsonPWolfeCWarburtonFA long-term follow-up of stroke patientsStroke19972835075129056603

- SharpeMHawtonKHouseAMood disorders in long-term survivors of stroke: associations with brain lesion location and volumePsychol Med200920048158282284390

- AstromMAdolfssonRAsplundKMajor depression in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinal studyStroke19932479769828322398

- ParadisoSVaidyaJTranelDKosierTRobinsonRNondysphoric depression following strokeJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci2008201526118305284

- MastBCerebrovascular disease and late-life depression: a latent-variable analysis of depressive symptoms after strokeAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200412331532215126233

- ParadisoSOhkuboTRobinsonRVegetative and psychological symptoms associated with depressed mood over the first two years after strokeInt J Psychiatry Med19972721371579565720

- FedoroffJStarksteinSParikhRPriceTRobinsonRAre depressive symptoms nonspecific in patients with acute stroke?Am J Psychiatry19911489117211761882994

- DesmondDRemienRMoroneyJSternYSanoMWilliamsJIschemic stroke and depressionJ Int Neuropsychol Soc200390342943912666767

- SteinPSliwinskiMGordonWHibbardMDiscriminative properties of somatic and nonsomatic symptoms for post stroke depressionClin Neuropsychol1996102141148

- SpallettaGBriaPCaltagironeCSensitivity of somatic symptoms in post-stroke depression (PSD)Int J Geriatr Psychiatry200520111103110416250074

- MagniEFrisoniGRozziniRDe LeoDTrabucchiMDepression and somatic symptoms in the elderly: the role of cognitive functionInt J Geriatr Psychiatry1998116517522

- GusevEBogolepovaADepressive disorders in stroke patientsNeurosci Behav Physiol200939763964319621267

- GottfriesCIs there a difference between elderly and younger patients with regard to the symptomatology and aetiology of depression?Int Clin Psychopharmacol1998135S13S189817615

- CarstensenLFungHCharlesSSocioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of lifeMotiv Emot2003272103123

- ShulmanKConceptual problems in the assessment of depression in old agePsychiatr J Univ Ott19891423643662668990

- ChristensenHJormAMackinnonAAge differences in depression and anxiety symptoms: a structural equation modelling analysis of data from a general population samplePsychol Med1999290232533910218924

- AbenIVerheyFHonigALodderJLousbergRMaesMResearch into the specificity of depression after stroke: a review on an unresolved issueProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200125467169011383972

- OuimetMPrimeauFColeMPsychosocial risk factors in poststroke depression: a systematic reviewCan J Psychiatry200146981982811761633

- HackettMAndersonCPredictors of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studiesStroke200536102296230116179565

- RobinsonRStarrLKubosKPriceTA two-year longitudinal study of post-stroke mood disorders: findings during the initial evaluationStroke19831457367416658957

- ParadisoSRobinsonRGender differences in poststroke depressionJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci199810141479547465

- MorrisPRobinsonRRaphaelBSamuelsJMolloyPThe relationship between risk factors for affective disorder and poststroke depression in hospitalised stroke patientsAust N Z J Psychiatry19922622082171642612

- StroberLBArnettPAAssessment of depression in three medically ill, elderly populations: Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and strokeClin Neuropsychol200923220523018609323

- WhyteEMulsantBPost stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatmentBiol Psychiatry200252325326412182931

- SchwartzJSpeedNBrunbergJBrewerTBrownMGredenJDepression in stroke rehabilitationBiol Psychiatry199333106946998353164

- KotilaMNumminenHWaltimoOKasteMDepression after stroke: results of the FINNSTROKE StudyStroke19982923683729472876

- AndersenGVestergaardKIngemann-NielsenMLauritzenLRisk factors for post-stroke depressionActa Psychiatr Scand20079231931987484197

- GabaldónLFuentesBFrank-GarcíaADíez-TejedorEPoststroke depression: importance of its detection and treatmentCerebrovasc Dis200724118118817971654

- GordonWHibbardMPoststroke depression: an examination of the literatureArch Phys Med Rehabil19977866586639196475

- HackettMAndersonCTreatment options for post-stroke depression in the elderlyAging Health20051195105

- Turner-StokesLHassanNDepression after stroke: a review of the evidence base to inform the development of an integrated care pathway. Part I: Diagnosis, frequency and impactClin Rehabil200216323124712017511

- LaidlawKDoloresG-TAnnMSLaryWTPost-stroke depression and CBT with older peopleHandbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies with Older AdultsNew YorkSpringer2007233248

- GuptaAPansariKShettyHPost-stroke depressionInt J Clin Pract200256753153712296616

- AgrellBDehlinOComparison of six depression rating scales in geriatric stroke patientsStroke1989209119011942772980

- SheikhJYesavageJGeriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter versionClin Gerontol1986512165173

- Carod-ArtalFFerreira CoralLTrizottoDMenezes MoreiraCPoststroke depression: prevalence and determinants in Brazilian stroke patientsCerebrovasc Dis200928215716519556768

- TangWUngvariGChiuHSzeKYuALeungTScreening post- stroke depression in Chinese older adults using the hospital anxiety and depression scaleAging Ment Health20048539739915511737

- JohnsonGBurvillPAndersonCJamrozikKStewart-WynneEChakeraTScreening instruments for depression and anxiety following stroke: experience in the Perth community stroke studyActa Psychiatr Scand20079142522577625207

- IncalziRCesariMPedoneCCarboninPConstruct validity of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in older medical inpatientsJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol2003161232812641369

- DiamondPHolroydSMacciocchiSFelsenthalGPrevalence of depression and outcome on the geriatric rehabilitation unitAm J Phys Med Rehabil19957432142177779332

- StilesPMcGarrahanJThe Geriatric Depression Scale: a comprehensive reviewJ Clin Geropsychol19984289110

- TangWChanSChiuHCan the Geriatric Depression Scale detect poststroke depression in Chinese elderly?J Affect Disord200481215315615306141

- HealeyAKneeboneICarrollMAndersonSA preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards and the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen to screen for depression in older stroke survivorsInternational Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry200823553153618008393

- AdsheadFCodyDPittBBASDEC: a novel screening instrument for depression in elderly medical inpatientsBr Med J199230568503971392921

- YohannesABaldwinRConnollyMDepression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaireInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200115121090109611180464

- McCreaDArnoldEMarchevskyDKaufmanBThe prevalence of depression in geriatric medical outpatientsAge Ageing19942364654679231939

- CarlC BellDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of MentalDdisorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- RiglerSManagement of poststroke depression in older peopleClin Geriatr Med199915476578310499934

- RabinsPBarriers to diagnosis and treatment of depression in elderly patientsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry199647983

- SchubertDTaylorCLeeSMentariATamakloWDetection of depression in the stroke patientPsychosomatics19923332902941410202

- HackettMAndersonCHouseAXiaJInterventions for treating depression after strokeStroke2009407e487e488

- AlexopoulosGBuckwalterKOlinJMartinezRWainscottCKrishnanKComorbidity of late life depression: an opportunity for research on mechanisms and treatmentBiol Psychiatry200252654355812361668

- TharwaniHYerramsettyPMannelliPPatkarAMasandPRecent advances in poststroke depressionCurr Psychiatry Rep20079322523117521519

- KatonaCManaging depression and anxiety in the elderly patientEur Neuropsychopharmacol200010S427S43211114487

- PevelerRCARodinGDepression in medical patientsBMJ2002325735614915212130614

- BhogalSTeasellRFoleyNSpeechleyMHeterocyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment and prevention of poststroke depressionJ Am Geriatr Soc20055361051105715935033

- AndersonCHackettMHouseAInterventions for preventing depression after strokeCochrane Database Syst Rev20042CD00368915106212

- HackettMAndersonCHouseAManagement of depression after stroke: a systematic review of pharmacological therapiesStroke200536510921097

- RobinsonRJorgeRMoserDEscitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2008299202391240018505948

- CaoCPatelVReddyCHovakimyanNLavretskyEWiseKAre phase and time-delay margin always adversely affected by high gains? Available from: http://www.engr.uconn.edu/~ccao/caopaper/CaoAIAA06Phase.pdfAccessed July 15, 2010

- LingamVRLLGrovesLOhSHMethylphenidate in treating poststroke depressionJournal of Clinical Psychiatry 19884941511533356672

- LazarusLMobergPLangsleyPLingamVMethylphenidate and nortriptyline in the treatment of poststroke depression: a retrospective comparisonArch Phys Med Rehabil19947544034068172499

- LazarusLWinemillerDLingamVEfficacy and side effects of methylphenidate for poststroke depressionJ Clin Psychiatry199253124474491487474

- GradeCRedfordBChrostowskiJToussaintLBlackwellBMethylphenidate in early poststroke recovery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyArch Phys Med Rehabil1998799104710509749682

- SnowVLascherSMottur-PilsonCPharmacologic treatment of acute major depression and dysthymia: clinical guideline, Part 1Ann Intern Med2000132973874210787369

- WilliamsLSDepression and stroke: cause or consequence?Semin Neurol200525439640916341996

- PaolucciSEpidemiology and treatment of post-stroke depressionNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20084114515418728805

- ScoginFWelshDHansonAStumpJCoatesAEvidence-based psychotherapies for depression in older adultsClin Psychol: Sci Pract2006123222237

- WatkinsCAutonMDeansCMotivational interviewing early after acute stroke: a randomized, controlled trialStroke20073831004100917303766

- Gallagher-ThompsonDSteffenAThompsonLVandenbulckeMHandbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies with Older AdultsNew YorkSpringer2008

- GebretsadikMJayaprabhuSGrossbergGMood disorders in the elderlyMed Clin North Am200690578980516962842

- KempBCorgiatMGillCEffects of brief cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy on older persons with and without disabling illnessBehave Health Ageing199222128

- AustralianRDepressionNAustralian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depressionAust N Z J Psychiatry200438638940715209830

- LincolnNFlannaghanTCognitive behavioral psychotherapy for depression following stroke: a randomized controlled trialStroke200334111111512511760

- AndersonCSkeggPWilsonRHackettMSnellingJGroverAUse of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in New Zealand: a review of efficacy, safety and regulatory controlsWellington, New ZealandMinistry of Health2005

- KellyKZisselmanMUpdate on electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc200048556056610811552

- MurrayGSheaVConnDElectroconvulsive therapy for poststroke depressionJ Clin Psychiatry19864752583700345

- CurrierMMurrayGWelchCElectroconvulsive therapy for post-stroke depressed geriatric patientsJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci1992421401441627974