Abstract

Background

A substantial disadvantage of psychopharmacological treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is the impact on sexual dysfunction. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the oil of Rosa damascena can have a positive influence on SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (SSRI-I SD) of male patients who are suffering from MDD and are being treated with SSRIs.

Method

In a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial, a total of 60 male patients treated with an SSRI and suffering from MDD (mean age =32 years) and SSRI-I SD were randomly assigned to take either verum (R. damascena oil) or a placebo. Patients completed self-ratings of depression and sexual function at baseline, at 4 weeks later, and at the end of the study, 8 weeks after it started.

Results

Over time, sexual dysfunction improved more in the verum group than in the control group. Improvements were observed in the verum group from week 4 to week 8. Self-rated symptoms of depression reduced over time in both groups, but did so more so in the verum group than in the control group.

Conclusion

This double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial showed that the administration of R. damascena oil ameliorates sexual dysfunction in male patients suffering from both MDD and SSRI-I SD. Further, the symptoms of depression reduced as sexual dysfunction improved.

Introduction

Among psychiatric disorders, major depressive disorders (MDDs) merit particular attention because they are among the most prevalent lifetime psychiatric disorders.Citation1 Not surprisingly, Murray and Lopez, on the basis of data obtained by using the Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years instrument to assess “the sum [of the] years lost due to premature mortality and years lived with disability adjusted for severity”,Citation2 estimated that MDD will be the third leading cause of burden worldwide by 2020, with chronic lifelong risk for recurrent relapse, high morbidity, comorbidity, and mortality.Citation1 The core symptom of MDD is the loss of interests and pleasure in activities that were otherwise interesting and pleasant to the patient. This holds particularly true for sexual function. Not surprisingly, patients suffering from MDD report higher rates of sexual dysfunction than do members of a healthy population.Citation3–Citation7 Accordingly, sexual dysfunction is very often observed among patients suffering from MDD.

There are several options for the treatment of MDD. These include psychotherapy,Citation8,Citation9 physical activity,Citation1–Citation13 electroconvulsive therapy,Citation14,Citation15 and psychopharmacotherapy (antidepressants).Citation16 In this paper, we focus on the psychopharmacological treatment of MDD.

The explanation for the occurrence of MDD in terms of monoamine deficiency (depletion of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the central nervous system)Citation17 argues for treatment with antidepressants (selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants, and serotonin antagonist reuptake inhibitors) that should increase monoamine levels.Citation18,Citation19 However, several studies indicate that the efficacy of antidepressants is limited; a therapeutic effect is observed at most in 70% of patients suffering from MDDCitation20 with maximum adherence of 50% 4 weeks after starting treatment.Citation21 This is probably due to the 2-week or greater time lag for antidepressant to take effect,Citation20 and is probably also due to various adverse side effects such as weight gain, dry mouth, and sexual dysfunction.Citation22

This last side effect, SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction (SSRI-I SD), is considered one of its most disturbing and disruptive side effects.Citation23–Citation25 Indeed, SSRIs can have a negative impact on any or on all phases of the sexual cycle by causing a decreased libido, an impairment in arousal, and erectile dysfunction; SSRIs are most commonly associated with delayed ejaculation and absent or delayed orgasm.Citation26 On the basis of a meta-analysis of 31 studies, including a total of 10,130 patients, Serretti and ChiesaCitation27 concluded that the total rate of sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs ranged from 25.8% to 80.3% and was significantly higher than the placebo rate of 14.2%. More specifically, Clark et alCitation24 reported that the SSRIs citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline and the SNRI venlafaxine were associated with significantly greater rates (70%–80%) of reported total sexual dysfunction, including negative impacts on desire, arousal, and orgasm, than was the placebo. In this regard, Garlehner et alCitation28 found that paroxetine, citalopram, and venlafaxine, when compared with other antidepressants (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, nefazodone, sertraline), were associated with a higher rates of reported sexual dysfunction, such as complaints of erectile dysfunction in men and decreased vaginal lubrication in women. In addition, citalopram was associated with reduced sperm quality.Citation29

How can SSRI-I SD be explained? In the absence of a conclusive neurophysiological rationale, the following hypotheses are advanced: 1) whereas sexual dysfunction occurs through several brain pathways, it is assumed that at least one pathway that involves increases in serotonin (5-HT) leads to an inhibition of the ejaculatory reflex by serotonergic neurotransmissionCitation30 and stimulation of post-synaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors;Citation31,Citation32 2) decreases in the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from the substantia nigra have been observed;Citation31,Citation32 3) the inhibition of nitric oxide synthase has been observed;Citation33 4) increases in corticolimbic 5-HT levels seem to be strongly associated with reductions in sexual desire, ejaculation, and orgasm.Citation34,Citation35 It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that sexual dysfunction is observable in 30%–80% of patients after they begin taking SSRIs.Citation23,Citation24,Citation27,Citation35,Citation36 Again unsurprisingly, sexual dysfunction seems to be one of the main reasons for discontinuing the intake of SSRIs,Citation37–Citation39 a pattern observed in up to 90% of patients treated with SSRIs.Citation40 Therefore, it is important to identify strategies that can alleviate SSRI-I SD.Citation25,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40

SSRI-I SD is regarded as such a serious disability probably because for humans, sexual activity and sexual intimacy may serve at least four distinct goals: 1) exploring one’s partner’s values; 2) reproduction; 3) pair-bonding and pair stabilization;Citation41 and 4) joy Citation42–Citation45 or quality of life.Citation25,Citation45 Among humans, sexual activity within couples usually signifies exclusivity, intimacy, and bond-reinforcing behavior.Citation41 The sexual activity and sexual intercourse in heterosexual couples can occur under many different conditions: 1) before and after the female’s fertile phase (ovulation); 2) during pregnancy; and 3) in females, during post-menopausal stage, thus indicating that, for heterosexual couples, sexual intercourse must serve needs beyond mere reproduction. Further, unlike with bonobos and chimpanzees, who belong to the two species closest to humans and who are sexually active in the presence and sight of other group members, humans, in all cultures and regardless of sexual orientation, engage in sexual relations in private and beyond the view of others; these practices further reinforce exclusive intimacy between partners. Given the exclusivity of sexual activity and its importance to bonding and bonding quality, it is not surprising its impairment is regarded as distressing and disturbing both for the individual and for couple-related quality of life. This holds particularly true for patients suffering from MDD, even during the recovery phase. For example, Clayton et alCitation25 reported that among patients suffering from MDD, the use of SSRIs was associated with sexual dysfunction and hence had further implications for compliance and distress for the patient and her or his sexual satisfaction.

Overall, the evidence strongly supports the view that among humans, sexual activity has importance beyond mere reproduction, that it is seriously impaired during MDD, and that the most disturbing side effect of SSRI treatment is SSRI-I SD.

Recommended treatments of SSRI-I SD involve commercially available medications such as sildenafil (Viagra®),Citation46,Citation47 tadalafil (Cialis®),Citation47 mianserin,Citation48 and bupropion.Citation49 Further, several case reports have been published that focus on the use of antidotes such as cyproheptadine and on augmenting agents including gingko biloba, sildenafil, tadalafil, amantadine, bethanechol, bromocriptine, bupropion, dextroamphetamine, granisetron, loratadine, methylphenidate, mianserin, mirtazapine, nefazodone, neostigmine, pemoline, pramipexole, ropinirole, trazodone, vardenafil, and yohimbine. (Extensive reviews are provided by Segraves and BalonCitation50 and by Balon alone).Citation35 However, NurnbergCitation40 concludes that:

….despite several thousand published reports on treatment modalities based on heuristic post hoc hypotheses of central serotonin inhibition and those involving agonist, antagonist, partial agonist, switching, augmentation, and waiting management approaches, no evidence-based data are available to support those treatment modalities, leaving patients exposed to random pharmacology.

Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmacological treatment for SSRI-I SD, and there is a shortage of randomized, placebo-controlled, and double-blind clinical trials of potential treatments. To address the latter issue, the aim of the present study was to conduct a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial examining the effect of R. damascena oil, a herbal agent, on SSRI-I SD among male patients suffering from MDD.

In the context of more traditional treatments based on phytopharmaca, the oil of R. damascena is particularly worthy of attention because within the long history of Persian medicine, R. damascena has been well known for its positive effects on mood, on a broad range of illnesses and diseases, and, most importantly, on sexual dysfunction.Citation51 R. damascena is a hybrid rose species predominantly grown in Iran, Turkey, and Bulgaria to produce rose oil and rose water to be used in perfume and in the cosmetic and food industries. The cultivation and consumption of R. damascena in Iran has a long history, and Iran is one of its origins.Citation52 It is believed that the crude distillation of roses for the oil originated in Persia in the late 7th century AD and spread to the provinces of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century. Iran was the main producer of rose oil until the 16th century and exported it to destinations all around the world.Citation53,Citation54 The extract has also been found to have medicinal properties. It has shown antimicrobial activity. It also has been reported to protect neurons against amyloid β toxicity, a major pathological component of Alzheimer’s disease, and to protect rats against seizures.Citation55–Citation58 The active components of R. damascena are not known. R. damascena oil is composed of a large number of volatile organic compounds including various terpenes such as citronellol, heneicosane, and disiloxane.Citation59 The marc, material left after rose oil is extracted, has significant polyphenol content, including quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, and gallic acid, though the predominant molecules have been suggested to be glycosides of quercetin and kaempferol.Citation60 With regard to the effects of R. damescena on sexual dysfunction, we currently lack evidence based on double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trials. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that the adjuvant administration of R. damascena oil has a favorable effect on sexual dysfunction among male patients suffering from MDD and SSRI-I SD.

The following three hypotheses were formulated. First, following Boskabady et alCitation51 we anticipated the adjuvant administration of R. damascena oil would improve sexual dysfunction among male patients suffering from MDD and SSRI-I SD. Second, we expected that the administration of R. damascena would alleviate symptoms of depression. Third, we expected that the improvements in symptoms of depression and of sexual dysfunction would be associated.

Method

Study design

The study entailed an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The entire study was approved by the local ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki (trial registration number: IRCT2013100814333N10; http://www.irct.ir.).

Procedure and sample

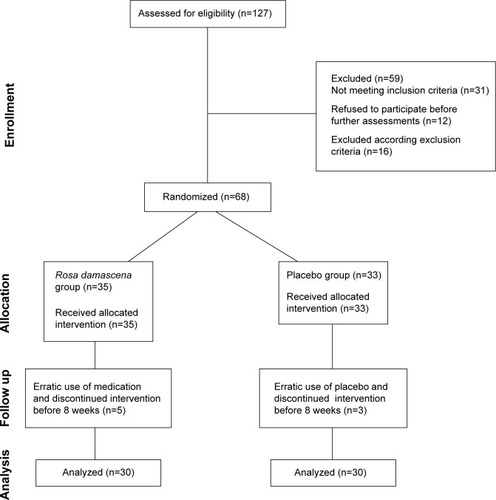

shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flowchart for patient sampling. Male patients who were diagnosed with MDD, treated with SSRIs, and complained about sexual dysfunction after commencement of the SSRI regimen were recruited between October 2013 and June 2014 at the Outpatients Clinic of Farabi Hospital, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences in Kermanshah, Iran. So that only patients suffering from MDD and experiencing sexual dysfunction after starting the SSRI regimen were included, trained professional psychiatrists performed interviews based on the structured clinical interview for psychiatric disorders (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview).Citation61 Eligible patients (number [n]=127) were fully informed about the study aims and procedure and about the confidential nature of data selection and data handling, and all of the patients gave their written informed consent. At that time, all eligible patients were in an acute depressive state according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria.Citation62 Prior to being enrolled in the present study, patients had been treated with and stabilized on an SSRI (standard medication) for at least 6 weeks. The treatment regimen remained unaltered throughout the 8-week duration of the study.

Figure 1 CONSORT diagram showing the flow of participants through each stage.

A male patient was included in the study if the following criteria were met: 1) he was suffering from an MDD that was diagnosed by a psychiatrist and was based on the DSM-5 criteria;Citation62 2) he was suffering from SSRI-I SD according to the DSM-5; 3) he scored at least 19 points or more on the self-rated depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and could thus be diagnosed with moderate major depression; 4) he scored 2 points or less for self-rated sexual dysfunction, as assessed via the Brief Sexual Function Inventory (BSFI);Citation63 5) he had continuous pharmacological treatment with SSRIs for at least 6 weeks prior to entering the study; and 6) he signed a written informed consent form.

Subjects were excluded if they met any of these criteria: 1) the subject did not meet the inclusion criteria as described previously; 2) he withdrew from the study; 3) he was taking any medication or drug that may affect sexual function; 4) he had any underlying medical or psychiatric disorder (except MDD) that may interfere with sexual function; or 5) he reported side effects (changes in physical and psychological well-being) related to adjuvant medication (intake of either the verum or the placebo). No side effects were reported at any time during the study.

Of the 127 patients screened, 68 were randomly assigned either to the verum group or to the placebo group. Randomization occurred as follows: 35 blue (for verum) and 35 red (for placebo) chips were put in a ballot box and stirred; patients drew a chip and were then assigned to the corresponding group. Neither the patients nor the hospital staff responsible for the randomization knew the group to which any of the subjects had been assigned. Furthermore, none of the personnel involved in the study knew the group to which any of the patients had been assigned. The principal investigator, Vahid Farnia, was not involved in performing the study.

At baseline, 35 patients were assigned to the verum group and 33 were assigned to the placebo group. The two groups did not differ with respect to age (verum: mean age =32.45 years, standard deviation =5.68 years; placebo: mean age =34.02 years, standard deviation =6.45 years; t(66)=1.34, P=0.54), symptom severity, or sexual dysfunction (). At follow-up, five patients dropped out of the verum group, and three dropped out of the placebo group. However, statistical computation was performed with the intention-to-treat algorithm and not with the per-protocol algorithm.

Table 1 Descriptive overview of the sexual dysfunction and depressive symptoms scores each group (verum versus placebo) for each assessment time (baseline, week 4, and week 8)

Medication

Patients took their standard SSRI-medications (duloxetine, escitalopram, venlafaxine, or sertraline). Dosages were individually adapted to patients and kept constant for 6 weeks prior to the start of the study in order to achieve treatment efficacy. Next, patients took either verum or placebo in the morning. The verum dosage was 2 mL/day and contained 17 mg Citronellol of essential oil of R. damascena (drops), whereas the placebo consisted of 2 mL/day of an oil–water solution with an identical scent. The verum and placebo flacons were identical in shape, weight, look, and, once opened, scent.

(The verum was based on at least 5.8 mg citronellol in each mL of product; the active ingredients are citronellol, geraniol, nerol, linalool, and phenyl ethyl alcohol. Additional components include linalool, saturated fatty alcohols beta-phenyl-ethyl alcohol, farnesol, terpinene-1-ol-4, acetates of the indicated alcohols, free acids, aldehydes [fatty and aromatic], geranial, neral, ketones, phenols, phenol esters, hydrocarbons, rose oxide, and stearoptene. The verum was manufactured by Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company in Kashan, Iran).

Assessing SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction

To assess SSRI-I SD, after the thorough psychiatric interview, psychiatrists also explored the sexual dysfunctions of each patient before he started the treatment with an SSRI, at least 6 weeks before each patient entered the study, and sexual dysfunction during the study. An SSRI-I SD was diagnosed in accordance with the DSM-5;Citation63 if all other factors were equal, sexual dysfunction emerged with the start of SSRI intake.

Instruments

Self-assessment of depressive symptoms by using the BDI

Patients completed the BDI,Citation64 which a self-report of symptoms of depression. The questionnaire consists of 21 items and covers such areas as depressive mood, loss of appetite, sleep disorders, and suicidal thoughts. Answers are given on 4-point Likert scales with the anchor points 0 (for “as always” or “no change”) and 3 (for “not able anymore” or “dramatic change”) and with higher scores reflecting greater severity of depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha =0.89).

Self-assessment of sexual dysfunction by using the BSFI

The BSFICitation63 contains eleven questions that cover five domains of sexual function: 1) sexual drive (two items); 2) erectile function (three items); 3) ejaculatory function (two items); 4) sexual problem assessment (three items); and 5) sexual satisfaction (one item). Answers are given on a 5-point Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 (none, big problem, or no activity) to 4 (always, no problem, or high activity) and with lower mean scores reflect greater sexual dysfunction (Cronbach’s alpha =0.91).

Statistical analysis

Preliminary calculations

To detect possible confounders, Spearman’s correlations were computed between sociodemographic data (age, education, civil status, medication intake, number of children) and indices of sexual dysfunction and depressive symptoms. All correlation coefficients were between −0.05 and 0.15 (Ps >0.56); accordingly, sociodemographic data were not introduced as possible confounders.

Next, a series of Pearson’s correlations was performed between dimensions of sexual dysfunction and depressive symptoms. Further, a series of analyses of variances (ANOVAs) for repeated measures was performed with the factors time (baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks) and group (verum versus placebo), and with sexual dysfunction areas (sexual drive, erections, ejaculations, problem assessment, overall satisfaction, and overall mean score) as dependent variables. Additionally, another ANOVA was computed with the factors time (baseline, 8 weeks) and group (verum versus placebo), with the dependent variable BDI score, and with Bonferroni–Holm corrections for P-values. Because of deviations from sphericity, ANOVAs for repeated measures (for the factor time with three values) were performed using Greenhouse–Geisser corrected degrees of freedom, although the original degrees of freedom are reported with the relevant Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon value (ε). For ANOVAs, effect sizes are indicated with the partial eta squared (η2), with 0.059 ≥ η2 ≥0.01 indicating small (S), 0.139 ≥ η2 ≥0.06 indicating medium (M), and η2 ≥0.14 indicating large (L) effect sizes. All computations were performed as intention-to-treat and the last observation carried forward.

The nominal alpha-level was set at 0.05; post hoc analyses were performed with Bonferroni–Holm corrections of P-values for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS® 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Apple MacIntosh®.

Results

Sexual dysfunction over time and between verum and placebo groups

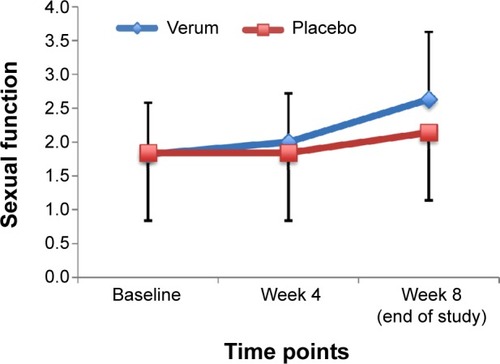

and show the descriptive and statistical overview of sexual function levels separately by assessment time (baseline, week 4, and 8 weeks later [at the end of the study]) and group (verum versus placebo).

Table 2 Overview of the inferential statistics for the factors time (baseline, week 4, week 8) and group (verum versus placebo) with sexual function as the dependent variable

Sexual function improved significantly over time. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni–Holm corrections for P-values showed that sexual dysfunction reduced from week 4 to week 8. All effect sizes were large. No statistically significant differences between the groups were observed.

Significant time × group interactions were observed for all sexual function variables. Effect sizes were large. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni–Holm corrections for P-values showed that sexual dysfunction was lower in the verum than in the placebo group at week 8. shows the mean values for the two groups over the three time points.

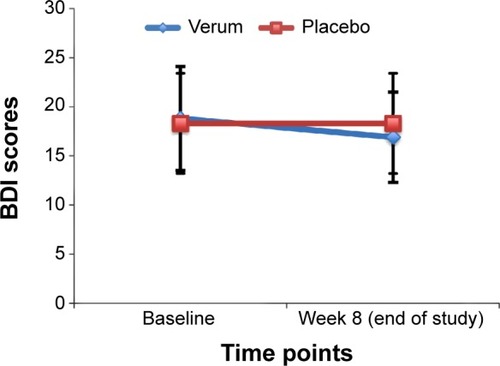

Depressive symptoms

Patients rated their depressive symptoms via the BDI at baseline and at the end of the study ( and and ). Depressive symptoms declined over time; the significant time × group interaction showed that depressive symptoms declined more in the verum group than in the placebo group.

Figure 3 Comparison of BDI scores between verum and placebo groups.

Abbreviation: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Correlations between sexual dysfunction and symptoms of depression

Correlating symptoms of depression at baseline and after 8 weeks (the end of the study) with sexual dysfunction showed that symptoms of depression and sexual dysfunction were unrelated (all rs<|0.11|, ps>0.41). When correlations were calculated separately for the verum and placebo group, the following pattern of results was observed: for the verum group, again, symptoms of depression and sexual function were unrelated (all rs<|0.13|, ps>0.38); for the placebo group, more severe symptoms of depression at baseline predicted greater sexual dysfunction at baseline, and after 4 and 8 weeks (rs>0.35, ps<0.05). A greater severity of depression symptoms after 8 weeks was associated with greater sexual dysfunction after weeks 4 and 8 of the study (rs>0.38, ps<0.05), but not with sexual dysfunction at baseline.

Discussion

The key findings of the present study are that among male patients suffering from both MDD and SSRI-I SD while being treated with an SSRI standard medication, adjuvant administration of R. damascena oil improved sexual dysfunction after 8 weeks more than the adjuvant administration of the placebo did. Symptoms of depression decreased in parallel, but not linearly. These results confirm the positive effect of R. damascena oil on SSRI-I SD in a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial and provide an important contribution to the literature on this condition.

Three hypotheses were formulated. Our first hypothesis was that the administration of R. damascena oil would improve sexual dysfunction more than a placebo would, and this theory was fully supported. Accordingly, the present study is a contribution to the current literature because, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time the success of an agent in the treatment of an SSRI-I SD in male patients suffering from MDD was proven in a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Our second hypothesis was that symptoms of depression would improve with adjuvant administration of R. damascena oil, and this was also supported. Symptoms of depression declined in both groups, but the decline was greater in the verum group ( and and ). Thus, we were also able to show that R. damascena oil had an adjuvant effect on symptoms of depression. However, the present pattern of results expands on previous findingsCitation51 because the results were based on a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Our third hypothesis was that improvements in depressive symptoms would occur in parallel to improvements in sexual dysfunction. This was not fully supported. Whereas a pronounced improvement was observed in depressive symptoms in patients treated with adjuvant R. damascena oil, improvements of the same extent were not observed in patients treated with the placebo. More importantly, a significant correlation between symptoms of depression and sexual dysfunction was only observed in the placebo group. Thus, whereas both symptoms of depression and sexual dysfunction are closely associated,Citation25 R. damascena oil seemed to have different effects on symptoms of depression and on sexual dysfunction in the verum group.

This last observation illustrates the primary limitation of the present study: the data available do not shed any light on the neurophysiological mechanisms by which R. damascena oil has positive effects on symptoms of either depression or sexual dysfunction. Hence, the following proposals are somewhat speculative; they are not strictly evidence-driven. With regard to improvements in sexual dysfunction, it is possible that agents of R. damascena oil have an antagonistic effect on the stimulation of the postsynaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptorsCitation30–Citation32 and that these agents have an antago nistic effect on the corticolimbic 5-HT receptors, which are responsible for increasing sexual desire, ejaculation, and orgasm.Citation34,Citation35 Additionally, it is possible that the agents of R. damascena agonistically increase the release of dopamine and norepinephrine in the substantia nigra,Citation31,Citation32 as well as disinhibiting nitric oxide synthase.Citation33 Further, R. damascena oil seems to have an antimicrobial effect, and has been reported to protect neurons against amyloid β toxicity, a major pathological component of Alzheimer’s disease, and to protect rats against seizures. More specifically, it is suggested that the agent glycoside quercetin is also responsible for improving neuronal activity, probably by inducing the expression of synaptic proteins synaptotagmin and post-synaptic density protein-95, at least in cultured rat cortical neurons.Citation65 Likewise, quercetin has been shown to reduce behavioral deficiencies, restore astrocytes and microglia, and reduce serotonin metabolism in a 3-nitropropionic acid-induced rat model of Huntington’s Disease.Citation66 Last, Merzoug et alCitation67 reported that quercetin mitigated Adriamycin-induced anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, immune dysfunction, and brain oxidative stress in rats.

With regard to the glycoside kaempferol, evidence from animal studies has shown an antidepressant and modulating effect on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and β amyloid in the neurons and hippocampus of double TgAD mice.Citation68

Overall, research on animal models suggest that both quercetin and kaempferol, two of the main agents of R. damascena oil, seem to have beneficial influences on symptoms of depression at the molecular level.

Moreover, we also observe that explaining the occurrence and maintenance of MDD in terms of monoamine deficiency is just one of several putative pathways by which MDD might be explained neurophysiologically and neuroendocrinologically. In this regard, more recently efforts have been made to further investigate the roles of the neuropeptide brain-derived neurotrophic factor on MDD,Citation10,Citation69,Citation70 on ketamine,Citation71 and statins.Citation72–Citation75 With regard to statins, by using a mouse model, Ludka et alCitation16 observed that after acute atorvastatin treatment, the antidepressant effect seemed to be explained via the L-argininenitric oxide-cyclic guanosine mono-phosphate pathway; atorvastatin seemed to inhibit NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartatic acid) receptors and NO-cGMP (nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate) synthesis, leading to a down-regulation of excitatory processes. On a behavioral level, this down-regulation seems to be reflected in a reduction of symptoms of depression. However, it remains unclear to what extent the new pathways explaining MDD neurophysiologically and neuroendocrinologically may help to better understand the influence of the agents of R. damascena oil on both symptoms of depression and sexual dysfunction.

Despite the encouraging results, several limitations should be considered to prevent overgeneralization of the data. First, as we have noted, neither the precise effects of the agents of R. damascena, nor their neurophysiological and neuroendocrinological influences on MDD and SSRI-I SD, are well understood. Accordingly, the details of the underlying mechanisms remain, for the present, unresolved. Second, participants were selected and recruited from one study center; therefore, a systematic selection bias cannot be excluded. In this regard, third and most importantly, we cannot say whether an identical pattern of results would also have been observed with female patients. Fourth, the present pattern of results might have emerged because of other latent but unassessed psychological or physiological variables, which might have biased two or more dimensions in the same direction. Fifth, we relied on patients’ self-ratings; this might be considered a limitation with regard to symptoms of depression, although the assessment of sexual function does commonly rely on self-ratings. However, future research should also include experts’ ratings of symptoms of depression and global clinical impression. Sixth, other depression-related symptoms, such as cognitive performance and psychosocial interaction, along with traits such as social attractiveness,Citation41 should be assessed. Seventh, future studies might employ a more fine-grained and broader data collection approach with respect to patients’ self-ratings and experts’ ratings to allow detection of more subtle psychological changes. Last, given the strong associations between depressive symptoms and sleep, future studies on this topic might also assess sleep patterns.

Conclusion

Evidence from this double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled clinical trial shows that the administration of R. damascena oil improved sexual dysfunction in male patients suffering from both MDD and SSRI-I SD.

Acknowledgments

The present work is the doctoral thesis of Mehdi Shirzadifar. We thank Gioia Schultheiss for text editing and Nick Emler (University of Surrey, UK) for proofreading the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- JosefssonTLindwallMArcherTPhysical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic reviewScand J Med Sci Sports201424225927223362828

- MurrayCJLopezADGlobal mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global burden of disease studyLancet19973499063143614429164317

- JohannesCBClaytonAHOdomDMDistressing sexual problems in United States women revisited: prevalence after accounting for depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200970121698170620141709

- BonierbaleMLançonCTignolJThe ELIXIR study: evaluation of sexual dysfunction in 4557 depressed patients in FranceCurr Medl Res Opin2003192114124

- AngstJSexual problems in healthy and depressed personsInt Clin Psychopharmacol199813Suppl 6S1S49728667

- KennedySHRizviSSexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressantsJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929215716419512977

- ClaytonAHEl HaddadSIluonakhamheJPPonce MartinezCSchuckAESexual dysfunction associated with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatmentExpert Opin Drug Saf201413101361137425148932

- GraweKNeuropsychotherapyNeuropsychotherapieGöttingenHogrefe2004

- KanferFHReineckerHSchmelzerD[Self-management therapy: a textbook for clinical practice]. Selbstmanagement-Therapie: Ein Lehrbuch für die klinische Praxis5th edNew YorkSpringer2012

- Mota-PereiraJSilverioJCarvalhoSRibeiroJCFonteDRamosJModerate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorderJ Psychiatr Res20114581005101121377690

- CooneyGMDwanKGreigCAExercise for depressionCochrane Database Syst Rev20139CD00436624026850

- MuraGMoroMFPattenSBCartaMGExercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic reviewCNS Spectr201419649650824589012

- StantonRHappellBHaymannMReaburnPExercise interventions for the treatment of affective disorders – research to practiceFront Psychiatry201454624834058

- HaghighiMSalehiIErfaniPAdditional ECT increases BDNF-levels in patients suffering from major depressive disorders compared to patients treated with citalopram onlyJ Psychiatr Res20134790891523583029

- KellnerCHGreenbergRMMurroughJWBrysonEOBriggsMCPasculliRMECT in treatment-resistant depressionAm J Psychiatry2012169121238124423212054

- LudkaFKZomkowskiADCunhaMPAcute atorvastatin treatment exerts antidepressant-like effect in mice via the L-arginine-nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway and increases BDNF levelsEur Neuropsychopharmacol201323540041222682406

- HaslerGPathophysiology of depression: do we have any solid evidence of interest to clinicians?World Psychiatry20109315516120975857

- BauerMPfennigASeverusEWhybrowPCAngstJMöllerHJWorld Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, Task Force on Unipolar Depressive DisordersWorld Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 1: update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disordersWorld J Biol Psychiatry201314533438523879318

- HashimotoKEmerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorderBrain Res Rev200961210512319481572

- CastrénEIs mood chemistry?Nature Reviews Neuroscience200563241246

- CassanoPFavaMDepression and public health – an overviewJ Psychosom Res200253484985712377293

- ReichenpfaderUGartlehnerGMorganLCSexual dysfunction associated with second-generation antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder: results from a systematic review with network meta-analysisDrug Saf2014371193124338044

- GrafHWalterMMetzgerCDAblerBAntidepressant-related sexual dysfunction – perspectives from neuroimagingPharmacol Biochem Behav201412113814524333547

- ClarkMSJansenKBresnahanMClinical inquiry: How do antidepressants affect sexual function?J Fam Pract2013621166066124288712

- ClaytonAHEl HaddadSIluonakhamheJPPonce MartinezCSchuckAESexual dysfunction associated with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatmentExpert Opin Drug Saf201413101361137425148932

- RosenRCLaneRMMenzaMEffects of SSRIs on sexual function: a critical reviewJ Clin Psychopharmacol199919167859934946

- SerrettiAChiesaATreatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysisJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929325926619440080

- GarlehnerGHansenRThiedaPComparative Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Depression: Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 7RockvilleAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality2007 Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/7/59/Antidepressants_Final_Report.pdfAccessed: March 5, 2012

- ElnazerHYBaldwinDSTreatment with citalopram, but not with agomelatine, adversely affects sperm parameters: a case report and translational reviewActa Neuropsychiatr201426212512924855891

- SegravesRTEffects of psychotropic drugs on human erection and ejaculationArch Gen Psychiatry19894632752842645849

- ClaytonAHZajeckaJFergusonJMFilipiak-ReisnerJKBrownMTSchwartzGELack of sexual dysfunction with the selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor reboxetine during treatment for major depressive disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol200318315115612702894

- KanalyKABermanJRSexual side effects of SSRI medications: potential treatment strategies for SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunctionCurr Womens Health Rep20022640941612429073

- KeltnerNLMcAfeeKMTaylorCLMechanisms and treatments of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunctionPersp Psychiatr Care2002383111116

- MontejoALLlorcaGIzquierdoJARico-VillademorosFIncidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatientsJ Clin Psychiatry200162102111229449

- BalonRSSRI-Associated Sexual DysfunctionAm J Psychiatry200616391504150916946173

- KennedySHRizviSSexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of anti-depressantsJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929215716419512977

- BullSAHunkelerEMLeeJYDiscontinuing or switching selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitorsAnn Pharmacother200236457858411918502

- HuXHBullSAHunkelerEMIncidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: patient report versus physician estimateJ Clin Psychiatry200465795996515291685

- MaundETendalBHróbjartssonABenefits and harms in clinical trials of duloxetine for treatment of major depressive disorder: comparison of clinical study reports, trial registries, and publicationsBMJ2014348g351024899650

- NurnbergHGAn evidence-based review updating the various treatment and management approaches to serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated sexual dysfunctionDrugs Today (Barc)200844214716818389091

- SelaYShackelfordTKPhamMNEulerHADo women perform fellatio as a mate retention behavior?Pers Individ Diffs2015736166

- BussDEvolutionary Psychology: The New Science of MindEssexPearson2013

- DiamondJThe Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human AnimalNew YorkHarperCollins Publisher1992

- MestonCMBussDMWhy Women Have Sex: Understanding Sexual Motivations from Adventure to Revenge (and Everything in Between)New YorkHenry Holt and Company2009

- MillerGThe Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human NatureNew YorkRandom House2000

- DamisMPatelYSimpsonGMSildenafil in the treatment of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: a pilot studyPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry19991618418715014670

- TaylorMJRudkinLBullemor-DayPLubinJChukwujekwuCHawtonKStrategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medicationCochrane Database Syst Rev20135CD00338223728643

- DolbergOTKlagEGrossYSchreiberSRelief of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor induced sexual dysfunction with low-dose mianserin in patients with traumatic brain injuryPsychopharmacology2002161440440712073168

- DeBattistaCSolvasonBPoirierJKendrickELoraasEA placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study of adjunctive bupropion sustained release in the treatment of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunctionJ Clin Psychiatry200566784484816013899

- SegravesRTBalonRSexual Pharmacology: Fast FactsNew YorkWW Norton and Company2003

- BoskabadyMHShafeiMNSaberiZAminiSPharmacological effects of rosa damascenaIran J Basic Med Sci201114429530723493250

- ChevallierAThe Encyclopedia of Medicinal PlantsLondonDorling Kindersely1996

- RusanovKKovachevaNVosmanBMicrosatellite analysis of Rosa damascena Mill. accessions reveals genetic similarity between genotypes used for rose oil production and old Damask rose varietiesTheor Appl Genet2005111480480915947904

- Tabaei-AghdaeiSRBabaeiAKhosh-KhuiMMorphological and oil content variations amongst Damask rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) landraces from different regions of IranSci Hortic20071134448

- BasimEBasimHAntibacterial activity of Rosa damascena essential oilFitoterapia200374439439612781814

- ShokouhinejadNEmaneiniMAligholiMJabalameliFAntimicrobial effect of Rosa damascena oil on selected endodontic pathogensJournal of the California Dental Association201038212312620232691

- AwaleSTohdaCTezukaYMiyazakiMKadotaSProtective effects of rosa damascena and its active constituent on Aß(25–35)-induced neuritic atrophyEvid Based Complement Alternat Med201114913104219789212

- RamezaniRMoghimiARakhshandehHEjtehadiHKheirabadiMThe effect of Rosa damascena essential oil on the amygdala electrical kindling seizures in ratPak J Biol Sci200811574675118819571

- Loghmani-KhouzaniHSabzi FiniOSafariJEssential oil composition of Rosa damascena mill cultivated in central IranScientia Iranica2007144316319

- KumarNBhandariPSinghBGuptaAPKaulVKReversed phase-HPLC for rapid determination of polyphenols in flowers of rose speciesJ Sep Sci200831226226718172921

- SheehanDVLecrubierYSheehanKHThe Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10J Clin Psychiatry199859Suppl 2022339881538

- American Psychiatric AssociationThe Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlingtonAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2013

- MykletunADahlAAO’LearyMPFossåSDAssessment of male sexual function by the Brief Sexual Function InventoryBJU Int200697231632316430637

- BeckATBeck depression inventoryPhiladelphiaCenter for Cognitive Therapy1961

- XuSLZhuKYBiCWFlavonoids induce the expression of synaptic proteins, synaptotagmin, and postsynaptic density protein-95 in cultured rat cortical neuronPlanta Med201379181710171424243544

- ChakrabortyJSinghRDuttaDNaskarARajammaUMohanakumarKPQuercetin improves behavioral deficiencies, restores astrocytes and microglia, and reduces serotonin metabolism in 3-nitropropionic acid-induced rat model of Huntington’s diseaseCNS Neurosci Ther2014201101924188794

- MerzougSToumiMLTahraouiAQuercetin mitigates Adriamycin-induced anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, immune dysfunction, and brain oxidative stress in ratsNaunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol20143871092193324947870

- HouYAboukhatwaMALeiDLManayeKKhanILuoYAntidepressant natural flavonols modulate BDNF and beta amyloid in neurons and hippocampus of double TgAD miceNeuropharmacology201058691192019917299

- MikoteitTBeckJEckertAHigh baseline BDNF serum levels and early psychopathological improvement are predictive of treatment outcome in major depressionJ Psychopharmacol (Berl)20142311529552965

- GieseMBeckJBrandSFast BDNF serum level increase and diurnal BDNF oscillations are associated with therapeutic response after partial sleep deprivationJ Psychiatr Res2014591725258340

- IrwinSAIglewiczAOral ketamine for the rapid treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice careJ Palliat Med201013790390820636166

- HaghighiMKhodakaramiSJahangardLIn a randomized, double-blind clinical trial, adjuvant atorvastatin improved symptoms of depression and blood lipid values in patients suffering from severe major depressive disorderJ Psychiatr Res20145810911425130678

- ParsaikAKSinghBMuradMHStatins use and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Affect Disord2014160626724370264

- OtteCZhaoSWhooleyMAStatin use and risk of depression in patients with coronary heart disease: longitudinal data from the Heart and Soul StudyJ Clin Psychiatry201273561061522394433

- TuccoriMMontagnaniSMantarroSNeuropsychiatric adverse events associated with statins: epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention and managementCNS Drugs201428324927224435290