Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic inflammatory lung disease characterized by progressive and only partially reversible symptoms. Worldwide, the incidence of COPD presents a disturbing continuous increase. Anxiety and depression are remarkably common in COPD patients, but the evidence about optimal approaches for managing psychological comorbidities in COPD remains unclear and largely speculative. Pharmacological treatment based on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors has almost replaced tricyclic antidepressants. The main psychological intervention is cognitive behavioral therapy. Of particular interest are pulmonary rehabilitation programs, which can reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients. Although the literature on treating anxiety and depression in patients with COPD is limited, we believe that it points to the implementation of personalized strategies to address their psychopathological comorbidities.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as a disease state characterized by exposure to noxious agents resulting in airflow limitation that is not fully reversible, causing shortness of breath and significant systemic effects.Citation1 This definition covers a spectrum of respiratory diseases, and includes both the clinical diagnosis of chronic bronchitis and the pathological diagnosis of emphysema.Citation2 In clinical practice, COPD is defined by characteristically diminished air flow in lung function tests. Spirometry is required to make the diagnosis and staging in this clinical context;Citation3 the presence of a postbroncho-dilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) <0.70 confirms the presence of persistent airflow limitation and thus of COPD. Unlike asthma, the limitation is practically irreversible and usually worsens gradually over time.Citation4 This worsening is causally related to an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to inhaled harmful particles or gases, attributed – usually – to smoking.Citation5

COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and results in an economic and social burden that is both substantial and increasing.Citation6 COPD prevalence, morbidity, and mortality vary across countries and across different groups within countries. The Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that COPD will become the fourth leading cause of death and the seventh leading cause of disability-adjusted life year(s) lost worldwide by 2030.Citation7 The death rate associated with COPD has doubled in the past 30 years,Citation8 implying that the health-care system failed to address the problem.Citation9

Comorbidity studiesCitation10–Citation12 from Western and developing countries, inpatient and outpatient population, and younger and elderly patients reveal a substantial over-representation of anxiety and depression in COPD, from significant symptoms to full diagnostic mental disorders,Citation13 according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) taxonomic systems. Prevalence rates of both anxiety and depression in patients with COPD vary widely depending on the population surveyed and the measurement tools. Also, the overlap between symptoms of COPD disease and symptoms of anxiety and depression may contribute to the variations in prevalence figures, especially because questionnaires designed to screen for anxiety and depression include a large number of somatic complaints (poor sleeping pattern, anorexia, breathlessness, and fatigue).Citation14

Anxiety in COPD patients is often associated with clinical depression, and studies indicate that depressed COPD patients have a seven-fold risk to suffer from comorbid clinical anxiety compared to nondepressed COPD patients.Citation11,Citation15 There is an overlap in existing symptomatology between the two disorders, with fatigue, weight changes, sleep disturbance, agitation, irritability, and difficulty in concentrating appearing as common symptoms.Citation16

In outpatients with COPD, studies indicate rates of depression varying from 7% to 80% and that of anxiety from 2% to 80%.Citation14–Citation26 Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) ranges from 10% to 33%Citation27,Citation28 and of panic attacks or panic disorder (PD) from 8% to 67%.Citation28 In stable COPD, the prevalence of clinical depression ranges from 10% to 42% and that of anxiety between 10% and 19%.Citation29 In a systematic reviewCitation30 that focused on patients with severe COPD disease, the prevalence of depression ranged from 37% to 71% and that of anxiety from 50% to 75%, figures comparable to or higher than prevalence rates in other advanced diseases such as cancer, HIV, heart disease, and renal disease.

Comorbid psychological impairments in COPD patients predict increased functional impairment,Citation15,Citation31 disabilityCitation17 and morbidity,Citation32,Citation33 lower quality of life,Citation34,Citation35 and decreased adherence to the treatment.Citation36,Citation37 A systematic review and a meta-analysis have shown that depression and anxiety increase the risk of hospitalization for COPD patients.Citation9,Citation38 Also, patients with comorbidity spend twice as long time in hospitals and have increased mortality rates.Citation39–Citation42

Accordingly, recent consensus statements and guidelines on optimal care for COPD patients emphasize the need for assessment and adequate treatment of persisting anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients. Despite the high prevalence and considerable negative impact of coexisting psychopathology in COPD, the evidence about optimal approaches for managing depression and anxiety remains unclear and largely speculative.

The objectives of this paper are to provide an overview of the prevalence, impact, and pathophysiology associated with anxiety and depression in patients with COPD and to review studies on pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions, in an effort to highlight current knowledge and identify needs for future research.

Anxiety in patients with COPD

Anxiety disorder is a generalized term for a variety of abnormal and pathological fear and anxiety states, including GAD, PD, agoraphobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, phobic disorders, and traumatic stress disorders. Anxiety disorders are defined using established diagnostic criteria, eg, current versions of DSMCitation43 or ICDCitation44 criteria, while anxiety symptoms are assessed using formal psychological instruments, eg, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale,Citation45 Beck Anxiety Inventory,Citation46 and State–Trait Anxiety Inventory.Citation47 GAD and PD occur at a higher rate in patients with COPD compared with the general population.Citation48 Symptoms of anxiety are manifested in a variety of ways, including physiological signs of arousal, such as tachycardia, sweating, and dyspnea. Anxiety in patients with COPD is intimately linked with the fear of acute dyspnea attacks and essentially with the sense of suffocation and the fear of death.Citation49–Citation51

The prevalence of anxiety-related disorders in COPD is associated with reduced functional ability and rehospitalizations.Citation52 Common mechanisms for explaining this high association include factors related to smoking and dyspnea. Smoking is widely acknowledged as the most important environmental risk factor for the development of COPD,Citation53 and high levels of anxiety have been identified as a risk factor for the initiation of smoking.Citation54,Citation55 Thus people who develop COPD as a consequence of smoking probably experienced higher levels of anxiety than the general population prior to developing the disease, and moreover, these individuals may have a greater tendency to addiction since nicotine withdrawal is associated with greater symptoms of anxiety.Citation56–Citation58

Evidence also suggests pathophysiologic relationships among dyspnea, hyperventilation, and anxiety.Citation49 Physiological research has demonstrated both that respiratory rate is increased by anxiety and that the resulting rapid, shallow breathing pattern markedly worsens dyspnea in COPD.Citation59,Citation60 The key common physiological factors in COPD are increased ventilatory load, reduced ventilatory capacity, and increased neural respiratory drive, hyperinflation, and neuromechanical dissociation, leading to an efferent–afferent mismatch, which is fundamental to the origin of dyspnea.Citation61 When the sense of heightened effort increases beyond a certain threshold and/or the dissociation between neural drive and the mechanical response reaches a critical level (which likely varies between individuals), it will generate a strong emotional reaction (ie, fear, distress, and anxiety) in the individual, which in turn will precipitate conditioned behavioral (avoidance) responses.Citation62,Citation63 These strategies help to attenuate neuromechanical dissociation and to allay anxiety. In some patients these compensations are not possible, and the affective response can quickly escalate to overt panic and overwhelming feelings of lack of control.Citation64 Extreme fear and foreboding will, in turn, trigger patterned ventilatory and circulatory responses (via sympathetic nervous system activation) that can further amplify respiratory discomfort. The vicious cycle of breathlessness and anxiety conceptualized as “dyspnea–anxiety–dyspnea cycle” relationship suggests patients’ emotional response to breathlessness exacerbates their perception of breathlessness.Citation65 This cycle can be illustrated by the cognitive behavioral model of dyspnea, hyperventilation, and anxiety.Citation49 This positive feedback cycle states that individuals may misinterpret physical sensations such as dyspnea, leading to anxiety, further autonomic arousal, and increased dyspnea.Citation66,Citation67

Other theories proposed to explain the overlap of anxiety and panic attack symptoms with COPD are the hyperventilation model and the carbon dioxide hypersensitivity model. Hyperventilation in excess of metabolic need leads to a decrease in pCO2, causing a respiratory alkalosis that leads to vasoconstriction and typical panic symptoms such as light-headedness, numbness, tingling sensations, and shortness of breath, in healthy individuals.Citation60 In COPD patients, increased frequency of breathing predisposes to dynamic hyperinflation, due to the slow time constant for lung deflation. Hyperinflation increases the elastic load, work, and effort of breathing, reduces inspiratory reserve capacities, and exacerbates dyspnea.Citation68 In patients with severe COPD, chronic hypoventilation induces hypercapnia.Citation60 An increase in pCO2 levels has been shown to activate medullary chemoreceptors, which elicits a panic response by activating noradrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus.Citation95 Lactate acid, formed because of hypoxia is also linked to panic attacks, and evidence suggests that patients with both COPD and anxiety are hypersensitive to lactic acid and hyperventilation.Citation49 In other words, the pathogenesis of panic may be related to respiratory physiology by several mechanisms: the anxiogenic effects of hyperventilation, the catastrophic misinterpretation of respiratory symptoms, and/or a neurobiologic sensitivity to CO2, lactate, or other signals of suffocation. Consequently, there is a reason to believe that chronic pulmonary disease constitutes a risk factor for the development of panic anxiety related to repeated experiences with dyspnea and life threatening exacerbations of pulmonary dysfunction, repeated episodes of hypercapnia or hyperventilation, the use of anxiogenic medications, and the stress of coping with chronic disease.Citation69

Anxiety symptoms may distract patients from self-management of disease exacerbations.Citation70 Even a low intensity dyspnea attack is able to trigger panic anxiety which in turn heightens the sensation of dyspnea and sense of suffocation, thus creating a vicious cycle that forces many patients to restrict their daily activities.Citation70–Citation72 Patients with COPD usually describe their understanding of acute dyspnea as an experience inextricably related to anxiety and emotional functioning. As a result, this comorbidity leads to significant decrease in functional capacity, including phobic avoidance of activity because of anticipatory anxiety, further deconditioning, and misuse of anxiogenic medicationsCitation73 (β2 agonists, theophylline, and oral corticosteroids).

Recognition of the presence of this pathophysiological mechanism provides a more comprehensive assessment of the additional functional impairment experienced by the patient even if biological parameters and laboratory results are insufficient to justify the compromised ability to perform physical functions.Citation15,Citation21,Citation52 Sense of loss of control over the disease itself and loss of masteryCitation74,Citation75 over their ability to engage in personal and social activities engenders frustration and anxious feelings.

It is important to note that dyspnea at rest or on exertion does not correlate with the magnitude of anxiety-related symptoms, and furthermore, the magnitude of decrease in dyspnea with pharmacotherapy or exercise training is not associated with the reduction in anxiety-related symptoms, this indicates that there are other factors contributing to this relationship.Citation76 Additionally, although patients with panic report more catastrophic misinterpretations of bodily symptoms, they do not differ from patients without panic on measures of physical functioning, disease severity, shortness of breath, or psychological distress. Thus, it has been suggested that panic symptoms may reflect a cognitive interpretation of pulmonary symptoms rather than objective pulmonary status.Citation66

Studies indicate that anxiety and depression were not correlated with COPD severityCitation77 (as determined by FEV1% of predicted), and it is reported that dyspnea ratings were influenced by anxiety and depressive symptoms, whereas the physiological state scarcely influenced the anxiety and depressive symptomatology.Citation78 A possible explanation is that patients construe disease seriousness subjectively, which contributes to the development of the levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.Citation14

Depression in patients with COPD

Today, the ICD-10Citation44 and DSM-VCitation79 criteria for depression are the most common diagnostic tools. Different subtypes of depression have been defined, and the clinical course of depression is acknowledged to be variable with patients moving in and out the diagnostic subtypes over time. When it comes to depression in patients with severe somatic illness, the validity of DSM criteria may to a certain degree be questioned because it is difficult to decide when somatic symptoms are secondary to depression, or when they are secondary to somatic illness.Citation80 Severity of depression is determined by the number and level of symptoms, as well as the degree of functional impairment. Patients with COPD may have a spectrum of symptom severity ranging from short-term depressive symptoms or adjustment disorder with depressed mood to dysthymia up to major depression.

In a cluster of studies that have compared depressive disorders across various chronic illnesses, COPD patients suffer from depression with greater frequency and greater chronicity of mood symptoms.Citation81–Citation84 Also, few studiesCitation10,Citation52 have reported that approximately two-thirds of COPD patients with depression have moderate-to-severe depression, and in one study,Citation85 it was reported that approximately one-fourth of COPD patients had unrecognized subclinical depression.

Depression in patients with COPD is often marked by feelings of hopelessness and pessimism, reduced sleep, decreased appetite, increased lethargy, difficulties in concentration, social withdrawal, impairment in functional abilities and performing activities of daily living, poorer self-reported health, impaired self-management of disease exacerbations, and poor health behaviors.Citation52,Citation70,Citation86–Citation91 The correlation between depressed mood and disease severity is modest;Citation21 but depression symptoms are important correlates of perceived self-reported physical disability and poorer quality of life.Citation85 Guilty feelings stemming from the sense of burden patients impose to their environment, in combination with the responsibility they might think they have for the occurrence of the disease, especially concerning ex-smokers, aggravates depressive symptomatology.Citation92

According to studies, clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety were more prevalent in younger COPD patients, irrespective of clinical severity of COPD, perhaps because younger patients may find it difficult to come to terms with enforced changes in lifestyle, with this leading to increased psychological morbidity.Citation93

Recent studies suggest that depression in patients with COPD is a heterogeneous entity with multiple contributing etiologies including genetic predisposition, environmental losses and stressors, and direct damage to the brain mediated by the physiologic effects of chronic respiratory disease.Citation94

The genetic vulnerability plays a role in the eventual development of COPD in that adolescents and young adults who are depressed or have a history of depression are more likely to progress in their use of and dependence on nicotine.Citation54,Citation55,Citation96 Smoking, COPD, and depression form a dynamic model of circular causality, with depression playing a role in the initiation and maintenance of smoking, smoking leading to the development of COPD, and COPD in turn contributing to the genesis of depression.Citation94

Evidence suggests that the appearance of major depression or depressive symptomatology in patients suffering from a chronic disabling general medical condition is common and justified as a “reaction” to the losses imposed by the illness in both symbolic order and real grounds.Citation97 These losses may include functional impactsCitation98 such as inability to carry out prior occupational activities, shifted roles within the family, and social constellation, but also an insult to self-image that patients experience with the change in their general physical condition and somatic functioning.Citation94 Losses for patients with COPD increase with the gradual deterioration of the disease. DyspneaCitation65,Citation99 is the most common and disabling symptom experienced by COPD patients and is inextricably associated with feelings of despair, helplessness, and alienation, resulting in the apparent loss of interest for life and other people.

By the very nature of the disease process, COPD is associated with chronic, if often subclinical, hypoxemia. Low arterial oxygen saturation has been shown to be associated with periventricular white matter lesions,Citation100 which are also present in elderly patients with depression.Citation101 Several authors have investigated the relationship between chronic hypoxemia and neuropsychological function, and the consequences of chronic hypoxemia include both impaired cognitive function and depression.Citation102,Citation103 Most studies of hypoxemia and depression arise from the sleep apnea literature where one of the primary identified sequelae of recurrent nocturnal hypoxemia is depressed mood.Citation104

Both depression and COPD have been associated with processes that jeopardize the microvasculature of the brain,Citation105,Citation106 and there is evidence for systemic inflammation and elevated biomarkers of oxidative damage.Citation107 Although there are difficulties in quantification of inflammatory biomarkers, sTNFR-1 has shown a strong association with rates of depression in COPD patients.Citation108 In the absence of prior comorbidity, systemic inflammation in COPD may result in depression and IL-6 appears to play a particularly important role in humans and in animal models of depression.Citation109 A prospective cohort study indicated that the mean time elapsed between the diagnosis of COPD and the first episode of depression was 7.6 years.Citation110 The long-term use of systemic corticosteroids has also been related to depression in COPD, but results are inconclusive.Citation111

Although smoking, hypoxia, and inflammation have potential impact on the prevalence of depression in COPD, the strongest predictors of depression among patients with COPD are their severity of symptoms and reported quality of life.Citation33 The advantage to recognizing the interdependent relationship of these contributing factors is the corollary recognition that effective intervention in any one of them will have a cascading, positive impact on the others. Effectively targeting depression, lost functionality, or chronic hypoxemia will decrease morbidity in that dimension, and potentially in the others as well.

Treatment

Despite high prevalence rates and deleterious impact of comorbid anxiety and depression in COPD, only a limited number of studies have addressed its management,Citation26 accounting for the absence of recommendations regarding their treatment in the updated GOLD guidelines.Citation1 Only pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is suggested as treatment option (evidence A), which is also available for only a small percentage of patients.Citation112 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published clinical guidelines for the use of stepped approaches to psychological and/or pharmacological treatment of depression in people with long-term conditions.Citation113 In recognition of the expanding knowledge and the clinical importance of this area, we attempted to summarize existing empirical evidence based on studies implementing pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions to reduce clinical anxiety and depression in people with COPD.

Method

A literature search was conducted for studies examining the effect of anxiolytic and antidepressant medical treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), PR, and other complex interventions on anxiety and depressive symptoms in COPD patients, using PubMed databases. Essential keywords were “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” OR “COPD” AND “anxiety” OR “depression” to capture the target population. Intervention search terms comprised “medication” OR “pharmacological treatment” OR “SSRIs” OR “antidepressants” OR “TCAs” OR “SNRIs” OR “mirtazapine” OR “buspirone” OR “benzodiazepines” OR “psychological interventions” OR “cognitive behavioural therapy” OR “psychotherapy” OR “pulmonary rehabilitation” OR “group therapy” OR “complex interventions” OR “relaxation” OR “health education” OR “counselling” OR “behavioural interventions” OR “alternative treatments” OR “Tai Chi” OR “yoga”.

Eligibility criteria

Studies for inclusion were required to be in the English language and meet participant, intervention, comparator, and outcome criteria,Citation114,Citation115 for studies of controlled comparative design. We also included nonrandomized studies such as clinical trials, crossover studies, observational studies, and relevant review articles and meta-analyses. Participants were adults (men and women of age ≥18 years), with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD as defined by the GOLD standard, who were treated for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Mode of interventions was pharmacological and nonpharmacological, and was aimed at reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. The primary outcomes of interest were reduction in these symptoms following the administration of these interventions. The outcome was measured by changes from baseline anxiety and depression scores to posttreatment scores, employing validated psychological assessment instruments.

Quality assessment

The quality of included controlled comparative design studies was assessed by two authors independently with respect to the Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklists for risk of bias evaluation.Citation116 The methodological quality of full-text articles was assessed employing checklists from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.Citation300

Results

Electronic database searches yielded 637 records with 438 remaining after removal of duplicates. From the initial title screenings, 253 potentially relevant articles were identified and their abstracts were subsequently reviewed. Of these, 167 were excluded as they failed to meet inclusion criteria. Seventy-two studies and 14 reviews were retrieved in full text for further assessment.

Overview and effects of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions on anxiety and depression in COPD

– outline the characteristics of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions reported in the included studies. The results column describes the effects of interventions in narratives, thus enabling comparisons across various studies.

Table 1 Pharmacological treatment for anxiety and depression in COPD patients

Table 4 Comprehensive PR in COPD patients

Pharmacological treatment

Management of depression and anxiety in COPD patients starts with the correct diagnosis. Many patients suffer transitory mood symptoms during respiratory exacerbations and there is no evidence that these time-limited symptoms require specific treatment. NICE guidelinesCitation117 advise that antidepressants should not be routinely prescribed for physically ill patients with subthreshold symptoms of depression or mild-to-moderate depression. Pharmacological therapy must be considered when major depression is diagnosed to avoid its long-term effects on overall disability.Citation17,Citation118–Citation120 A recent study in USA reported that less than a third of COPD patients with major depression received appropriate treatment.Citation121 The importance of routine screening in COPD patients for depressive symptoms is considered paramount in order to initiate the most appropriate treatment (especially after acute exacerbations and when changes occur in patients’ circumstances).Citation122

All antidepressants have similar effectiveness but mainly differ based on type and severity of side effects. Based on which chemicals in the brain they affect, the main categories are tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), tetracyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants, norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors, and melatonergic antidepressants.

The choice of antidepressant depends on the pattern of depression,Citation123 and it is useful to differentiate between early- and late-onset depression,Citation94 because there is a distinct symptom profile that necessitates diverse treatment strategies. Late-onset depression or geriatric vascular depression after COPD diagnosis, caused by physiologic changes associated with COPD that have direct effect on brain’s vasculature, is characterized by more cognitive dysfunction, physical disability, limited insight, and psychomotor retardation and necessitates support networks and protection against continuous vascular damage. Late-onset depression has been found to be more refractory to treatment with antidepressants,Citation124,Citation125 associated with a greater degree of patient apathy,Citation126 and less often associated with a family history of depression.Citation127,Citation128 On the other hand, early-onset depression is defined as depression that develops prior to the diagnosis of COPD, often during an individual’s youth. This type of depression is often reflective of a genetic vulnerability to depression, which increases adolescents’ risk for developing addiction to nicotine and presents with more classic symptoms, but might have greater difficulty with smoking cessation.Citation129,Citation130

It is also necessary to consider that the prescribed medications should not cause sedation or respiratory depression in patients with chronic respiratory conditions. Plus, the ideal medication should have a low side effect profile, a short half-life with no active metabolites,Citation8 and provoke few drug interactions, especially when considering the other already administered medications for COPD.Citation131 The most commonly used agents in COPD are β2-adrenergic agonists and anticholinergic medication. β2-adrenergic agonists can cause dose-related prolongation of the QT interval and potassium loss. Thus coadministration with some SSRIs and TCAs that can prolong QT interval may result in additive effects and increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Also, the anticholinergic action of TCAs may be added to that of anticholinergic bronchodilators used in COPD. Besides pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetic interactions should be considered, and hence medications with the lowest potential to interfere with cytochrome P450 system should be considered.Citation132

In general, antidepressants seem to have little effect on ventilator drive, but caution should be taken while prescribing certain antidepressants (TCAs and mirtazapine) in COPD patients with hypercapnia.Citation112,Citation133 On the contrary, benzodiazepines may cause respiratory depression and should be avoided, especially for patients with COPD who are CO2 retainers.Citation134,Citation135 A recent prospective studyCitation136 evaluating the safety of benzodiazepines and opioids in patients with very severe COPD indicated that concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids in lower doses (<0.3 defined daily doses per day) was not associated with increased admissions or mortality, whereas higher doses (>0.3 defined daily doses per day) might increase mortality. Additionally, β-blockers are contraindicated in these patients, despite their anxiolytic effect due to their potential risk of bronchoconstriction.Citation73 Low-potency atypical antipsychotics in very small dosages may alleviate anxiety symptoms in these patients, but should be used with caution as they can have potential neurological and cardiovascular side effects.Citation26

Small, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressant drug therapy in patients with COPD did not demonstrate significant treatment effects, with the exception of one study, in 1992,Citation137 which indicated high efficacy for nortriptyline in improving short-term outcomes for depression, anxiety, cognitive function, and overall disability. Other TCAs have been tested, such as doxepine,Citation138 imipramine, and amitriptyline,Citation139–Citation142 with contradictory results. More recent studiesCitation143–Citation147 have used SSRIs, the current first-line medications for the management of depression, but most suffered from methodological flaws. In few randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, sertraline,Citation145,Citation146 fluoxetine,Citation143,Citation148 citalopram,Citation149 and paroxetineCitation147 offered improvements in quality of life, dyspnea, and fatigue. Start-up side effects with SSRIs include gastrointestinal upset, headache, tremor, and either psychomotor activation or sedation, which is frequently problematic in COPD patients. Treatment timelines necessitate checking the tolerance of medication during 1–3 weeks, then evaluating the response during 2–4 weeks, and if there is response, it is important to complete symptom resolution and move on to continuation and then maintenance phase. In case there is none or inadequate response, augmenting strategies are advised or change of medication is required.Citation14 Either way, it is necessary to consult a psychiatristCitation150 in cases of suicidal or self-injurious behavior, psychotic or bipolar depression, or other psychiatric comorbidities (eg, substance abuse, personality disorders). The presence of complex psychological issues, multimorbidity, frailty, and polypharmacy also necessitates integrated and comprehensive approach for the care of these people.Citation151

Concerning anxiety, several studies have investigated the effectiveness of specific medicationsCitation152 with contradictory results for buspironeCitation153,Citation154 and inconclusive results for SSRIs, even though they are better tolerated and can relieve symptoms of panic,Citation145,Citation146 but compliance may be poor.Citation143 A recent Cochrane reviewCitation155 on pharmacological interventions for the treatment of anxiety in COPD patients analyzed four studies and found insufficient evidence of benefit for any of medications included. Two studies using SSRIs showed a nonsignificant reduction in anxiety symptoms,Citation144,Citation156 while two other studies using TCA and azapirones did not show any improvement.Citation138,Citation154 Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin have also been prescribed for the treatment of anxiety symptoms in COPD patients.Citation73

Some authors reportCitation143,Citation157 that patients with COPD and psychiatric comorbidity are reluctant to take yet another medication, possibly because of stigma associated with the disease or denial, and as mentioned before, data supporting the efficacy of medication-only treatment are extremely limited.Citation158,Citation159

When implementing treatment strategies for COPD patients, it is important to remember that there is a greater possibility for medical comorbidities, increased risk for medication interactions, and greater physical debilitation than the community population.Citation160 An overview of studies on pharmacological treatment for anxiety and depression in COPD patients is summarized in .

Psychotherapeutic interventions

Patients prefer nondrug treatments,Citation161 and clinical guidelinesCitation117,Citation162 promote nonpharmacological interventions as first-line therapy for depression and anxiety in people with long-term conditions. NICE recommends use of low- (eg, self-help programs) or high-intensity (individual or group CBT) psychosocial interventions depending on the severity of mood symptoms.Citation163 Both individual and group therapy psychological interventions are useful in promoting more adaptive coping in COPD patients.Citation92

CBT

Evidence suggests that individualized or group CBT is the treatment of choice for addressing the maladaptive coping in the COPD patient with mental health difficulties, because of the time-limited and action-oriented nature of the intervention.Citation164 According to this psychotherapeutic approach, emphasis is given to the effect of cognitions on mood and behavior. This model of psychotherapy assumes that maladaptive, or faulty, thinking patterns cause maladaptive behavior and “negative” emotions. Maladaptive behavior is behavior that is counterproductive or interferes with everyday living.Citation14 The treatment focuses on changing an individual’s thoughts (cognitive patterns) in order to change his or her behavior and emotional state. Therapists attempt to make their patients aware of these distorted thinking patterns, or cognitive distortions, that fuel anxiety and depressive symptoms and change them (a process termed cognitive restructuring).Citation14 Therapy focuses on helping patients discover alternative solutions and promote more adaptive coping styles in order to overcome adversities and effectuate operational techniques to address their problems.Citation165–Citation167

Mental health guidelines recommend CBT as the treatment of choice for a range of mood and anxiety disorders and as an adjunct to other treatments. Low-intensity CBT-based psychosocial interventions are recommended for people with mild-to-moderate anxiety and/or depression, whereas high-intensity psychological interventions using CBT in combination with medication is recommended for people with moderate-to-severe depression.Citation162,Citation163 Not all aspects of CBT may be necessary to produce a therapeutic effect. Purely behavioral interventions can be as effective as CBT for patients with depression.Citation168

Some studies report that there is potential for psychological interventions to reduce anxiety and depression in people with COPD.Citation169,Citation170 A recent meta-analysis of four CBT studies for anxiety and depression in COPD patients indicated improvements in these symptoms.Citation171 Also, based on randomized controlled trials, CBT resulted in improvement in symptoms of anxiety and depression (), especially when used with exercise and education.Citation172

Table 2 Cognitive behavioral therapy in COPD patients

Group psychotherapy

Group psychotherapy is a financially attractive approach in response to the realities of limited resources, regardless of its theoretical orientation, because it involves fewer therapists, less therapist per person-hours, and serves more patients.

The group context and group process, if explicitly utilized within the principles of system dynamics, offers valuable healing opportunities.Citation14 Therapeutic principles,Citation173,Citation174 termed “therapeutic” factors, include the experience of relief from emotional distress through the free and uninhibited expression of emotion, feeling a sense of belonging, acceptance, and validation. Within a context that reflects the individual’s perception of reality, group members share experiences and feelings and develop social skills through a modeling process.

The therapist’s interventions facilitate group activities by taking advantage of the inherent assets of the team, ensuring that it runs efficiently with appropriate boundaries being maintained.Citation14

Relaxation therapy and alternative treatments

Relaxation therapy encompasses a range of techniques such as breathing exercises, sequential muscle relaxation, biofeedback, guided imagery, distraction therapy, hypnosis, meditation/mindfulness, and physical posture therapy.Citation175,Citation176 Often, some of these techniques are components of PR or are used as an adjunct to other therapies (eg, CBT).Citation112 The purpose of this therapy is to promote psychological change by effectively managing physiological changes accompanying anxiety. In other words, regulation of the sympathetic nervous system and management of the stimulation of certain regions of the hypothalamus facilitate the relaxation response.Citation177 In this perspective, relaxation techniques are often used to inhibit anxiety, increasing the patient’s perception of self-control or modulating his or her emotions, in order to promote the perceived well-being of the subject.

A meta-analysis of trials with relaxation-based therapies for COPD patients indicated statistically significant beneficial effects on both dyspnea and psychological well-being.Citation178 Another recent meta-analysis on the effects of relaxation techniques, of 25 randomized controlled trials including both inpatients and outpatients with COPD, showed a minor positive effect on respiratory function as well as a slight effect on levels of both the anxiety and depression. The higher effect size was found in the quality of life value.Citation176

Several other studies have investigated other types of relaxation approaches.Citation179 In a pilot study, the authors argued that the introduction of Tai Chi exercises was worth exploring in patients with COPD,Citation180 while in another study,Citation181 Yoga exercises were performed. Singing lessons have also been used as an intervention in patients with COPD.Citation182,Citation183 The basic theory is that singing lessons could improve quality of life or functional status in these patients.Citation184 Regarding these less traditional interventions, there is still lack of certainty about their applicability, their long-term effectiveness, the active component (physical or psychological), and how they can be incorporated into standard care.Citation185 An overview of studies on relaxation therapies and alternative treatments for anxiety and depression in COPD patients is summarized in .

Table 3 Relaxation therapy and alternative treatments

PR

Treatment strategies include PR, because it improves patient’s ability to participate in stress-reducing activities and increases their sense of self mastery. It also improves quality of life by increasing patients’ perception of available social supports.Citation186 According to the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, PRCitation187 is an evidence-based multidisciplinary and comprehensive intervention for patients with chronic respiratory diseases who are symptomatic and often have decreased daily life activities.

The ideal patient for PR is one with functional limitations, moderate-to-severe lung disease, who is stable on standard therapy, without comorbid serious or unstable medical conditions, willing to learn about the disease, and motivated to devote time and effort necessary to benefit from a comprehensive care program.Citation188

The interdisciplinary team of health-care professionals in PR may include physicians, nurses, respiratory and physical therapists, psychologists, and exercise specialists.Citation151 PR programs operate by means of progressive exercise, training of respiratory function, and psychoeducation, so that patients obtain better exercise tolerance with less dyspnea. The goal is to restore the patient to the highest possible level of independent function.Citation189 Patients are educated about their disease and learn breathing techniques to reduce air hunger and exercises to optimize oxygen use, and this in turn improves exercise tolerance. Key outcomes such as exercise capacity and overall health-related quality of life may be accurately measured.Citation190–Citation192

Exercise-based PR programs have been the most consistently helpful interventions for minor mood symptoms in COPD patients,Citation193–Citation195 but the greatest improvements in anxiety and depression are usually in those with the highest scores at baseline.Citation196 The paradox is that patients most likely to benefit from PR appear least likely to complete it.Citation197,Citation198 It is important therefore to be able to identify patients with COPD who may need additional support to complete a PR program in order to broaden benefit to all.

Several mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain the effect of exercise rehabilitation on mental health symptoms. Biological mechanisms associated with exercise activity include changes in central monoamine function,Citation199–Citation204 enhanced hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis regulation, increased release of endogenous opioids,Citation205–Citation207 and reduced systemic inflammation.Citation208,Citation209 In this way, regular physical activity may reduce depression and anxiety among patients undergoing PR. In addition, behavioral mechanismsCitation210–Citation215 associated with exercise activities operate synergistically to produce reductions of symptoms. Such mechanisms include active distraction from worrying thought patterns (rumination), increase of self-efficacy by providing patients with a meaningful mastery experience, and provision of daily pleasant events and regular social contact and support.

A recent systematic reviewCitation216 showed that PR is beneficial in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms, but the long-term benefit is unknown. Studies combining antidepressant pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy indicated more effective results than PR alone.Citation217,Citation218 Because both depression and anxiety may be manifested in physical symptoms during the course of a PR program, collaborative care is essential among all involved health-care professionals to ensure that patients’ problems are identified, evaluated, and treated.

The majority of PR programs have a primary exercise focus in order to recondition the legs and other peripheral muscles, making them more efficient as to oxygen needs, and thereby requiring relative less breathing to satisfy these oxygen requirements.Citation219 Additionally, PR programs teach breathing control exercises to patients and educate them in recognizing an impending dyspnea attack and preventing it, or controlling it, so they lose their fear of exerting themselves.Citation220

In PR settings, patients learn that they can have increases in activity levels and in dyspnea without perceiving that increase in dyspnea as a medical crisis. When patients experience their symptoms safely, they become desensitized by learning to distinguish between physical and emotional symptoms. Then, these patients can gradually take responsibility for the day-to-day management of their condition, with a result of improving their confidence, control, and autonomy.Citation221

PR should be offered to all COPD patients irrespective of disease severity, since they all get improvements,Citation222,Citation223 from mild COPDCitation224 to severe-to-very severe lung disease.Citation225,Citation226 Emphasis should be given to exercise training with respect to patients with mild-to-moderate disease, but for patients with severe-to-very severe COPD, PR programs should be tailored mostly toward dyspnea management and psychological support.Citation227,Citation228

In sum, the preponderance of recent evidence supports the utility of PR for reducing depression and anxiety and enhancing cognitive performance, but it is necessary to maintain the physical activity regimen to sustain the gains in physical fitness, mood, and cognitive performance, otherwise a relapse is inevitable.Citation193 Representative studies with PR programs for COPD patients are summarized in .

Discussion and recommendations

Mental health problems in COPD remain underdiagnosed and undertreated.Citation229 Although more than one-third of individuals with COPD experience comorbid symptoms of depression and anxiety,Citation230 available evidence suggests that less than one-third of COPD patients with such comorbidity are receiving appropriate treatment for this.Citation231 Every clinician caring for patients with COPD should have a high level of suspicion regarding the presence of mental health comorbidities since they are associated with poorer outcomes.Citation230

The first step to improve practice is to achieve earlier and more accurate diagnosis. It is not clear when screening should be doneCitation232,Citation233 and if it should be carried out with all COPD patients or just to those at higher risk of these comorbidities.Citation29 Current screening tools for anxiety and depression in patients with COPD were primarily validated for patients with other chronic diseases.Citation234–Citation237 The Hospital Anxiety Depression and the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventory scales have been recommended as the preferable choice of screening tools for anxiety and depression in patients with COPD.Citation29 Clinicians should be aware of the somatic overlap between anxiety and/or depression and COPD.Citation238,Citation239

Mild-to-moderate symptoms of anxiety and/or depression should not be ignored, and treatment should be considered. High-scoring patients should be referred to a mental health specialist for a comprehensive diagnostic assessment using structured clinical interviews. It is well known that physiological, functional, and psychosocial consequences of COPD are only poorly to moderately related to each other.Citation240 This means that a comprehensive assessment of the effects of COPD requires a battery of instruments that not only tap the disease-specific effects, but also the overall burden of the disease on everyday functioning and emotional well-being. Accurate assessment will ensure that treatment modalities are targeting the specific mental health problem taking into account individual factors, such as genetic predisposition, nicotine addiction, social support, other comorbidities, etc.

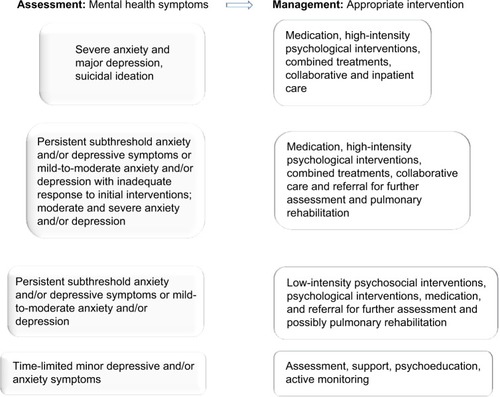

Identification of mental health problem should guide the choice of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, or other suitable intervention (). While treatment guidelines highlight the importance of recognizing and treating depression and anxiety in patients with COPD, there are few clear evidence-based pathways for the treatment of depression and anxiety. A GOLD report states that there is no evidence that anxiety and depression should be treated differently in the presence of COPD, so at this point of time guidelines are based on treatment of depression and anxiety for the general population.Citation1

Figure 1 Recommendations for appropriate interventions following assessment of mental health symptoms in patients with COPD.

In clinical practice, bidirectional associations between depression and/or anxiety and COPD imply the need to promote approaches that integrate physical and mental health care. The NICE has published clinical guidelines for managing depression in people with long-term conditions.Citation113 The guidelines review the evidence for the associated service-level interventions (such as stepped care and collaborative care) and psychosocial, psychological, and pharmacological interventions.

According to reviews and meta-analysis,Citation185,Citation230 current evidence for treatment options to reduce anxiety and depression in patients with COPD include pharmacological treatments, CBT, PR, relaxation therapy, and personalized interventions.Citation241,Citation242 PR has extensive evidence supporting its benefits, and it has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of both anxiety and depression in COPD patients.Citation216 Although there is lack of strong evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological treatment in patients with COPD with comorbid depression and anxiety, adding a depression- or anxiety-targeted treatment to the PR program may have additive therapeutic benefits.Citation225 Maximizing the efficiency of services is important as limited health resources allocated to PR programs mean that not every patient with COPD who might benefit has access to them.

In recent years, a model of care termed the collaborative-care model has been found to be associated with significant improvement in depression outcomes.Citation243–Citation245 Collaborative-care models that focus on building partnerships between mental health and other professionals to foster integration of care for people with complex morbidities present a fruitful framework for the management of mental health in COPD.Citation29 By definition, PR is an example of a collaborative-care model. In particular, the integration of PR and psychological therapies, such as CBT, has the potential to lead to significant patient benefits.Citation230 Contemporary research suggests that complex psychological and/or lifestyle interventions, which include a PR component, have the greatest effects on depression and anxiety in patients with COPD.Citation246

Most people with stable COPD are managed in primary care where recognition, assessment, and initial management of anxiety and depressive symptoms can be provided.Citation229 Tailoring mental health interventions to adapt not only to the unique needs of COPD patients but also to the current primary care setting is necessary. From the earliest consultations, we should acknowledge patients’ beliefs about their COPD and its management to better assess their likely responsiveness to treatment. We can then more effectively deliver from a menu of interventions in order to improve outcomes. Continuity of care implies that when COPD patients need hospitalization for the treatment of exacerbations, mental health issues should be more systematically addressed enhancing benefit for the many not the few.

Limitations

Including nonrandomized studies and other reviews and meta-analyses resulted in differences to varying degrees from the typical intervention review. Reporting results in narratives impeded the drawing of statistical conclusions about the interventions’ summary effect.

Future needs

Future research studies should focus on:

Identifying which components of PR are essential, its ideal length and location (hospital-based inpatient or outpatient, or community-based, home-based), the degree of supervision and intensity of training required, how long treatment effects persist, and the barriers of PR attendance and completion in real-life PR settings.

Determining the best treatment for specific COPD groups, eg, based on sex, severity of COPD, frequency of exacerbations, and type and severity of comorbid mental health problems, so the efficacy of treatments in different subgroups can be assessed.

Disentangling the contributions of exercise training, education, and CBT in a COPD population with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria for anxiety and depression severity and adequately powered RCTs.

Investigate a range of treatment options in COPD across all care settings, including comparison of different treatment options and various combinations.

Address the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of targeted treatment of anxiety and depression, of the different interventions (eg, optimal length of therapy; when to stop treatment in nonresponders; identifying predictors of success and failure).

Examine novel types of disease management interventions with respect to social and behavioral principles and models most relevant for COPD patients in order to increase their engagement and improve health outcomes.Citation247,Citation248

Develop properly “evidence-based” COPD care programs that proactively address mental health in order to optimize physical and mental health outcomes.

Conclusion

Patients suffering from COPD frequently experience comor-bid symptoms of anxiety and depression. Detection and recognition of these symptoms is of utmost importance as they are related to both disease progression, treatment, and rehabilitation procedures. Although the literature on treating anxiety and depression in COPD patients is limited, we believe that it points to a more multidisciplinary approach and to the implementation of personalized strategies to address both anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease [Updated 2015]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Accessed December 21, 2015

- National Heart Lung and Blood InstituteWhat is COPD? Updated July 31, 2013Bethesda, MDUS National Institutes of Health Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/copdAccessed January 9, 2016

- ZwarNAMarksGBHermizOPredictors of accuracy of diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practiceMed J Aust2011195416817121843115

- NathellLNathellMMalmbergPCOPD diagnosis related to different guidelines and spirometry techniquesRespir Res2007818918053200

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- LopezADShibuyaKRaoCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projectionsEur Respir J20062739741216452599

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med20063e44217132052

- EdmundsMScudderLExamining the relationships between COPD and anxiety and depressionHeart Lung200938344719150529

- PoolerABeechRExamining the relationship between anxiety and depression and exacerbations of COPD which result in hospital admission: a systematic reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014931533024729698

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJDepression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaireInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2000151090109611180464

- LacasseYRousseauLMaltaisFPrevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil200121808611314288

- AghanwaHSErhaborGESpecific psychiatric morbidity among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Nigerian general hospitalJ Psychosom Res20015017918311369022

- HillKGeistRGoldsteinRSAnxiety and depression in end-stage COPDEur Respir J200831366767718310400

- TselebisABratisDPachiAAnxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)ZirimisLPapazoglakisAChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: New ResearchNew York, NYNova Science Publishers20131540978-1-62081-848

- LightRWMerrillEJDesparsJAPrevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD: relationship to functional capacityChest19858735383965263

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med20061001767177416531031

- KatzPPJulianLJOmachiTAThe impact of disability on depression among individuals with COPDChest201013783884519933374

- McSweenyAJGrantIHeatonRKLife quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med198214234734787065785

- IsoahoRKeistinenTLaippalaPChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and symptoms related to depression in elderly personsPsychol Rep1995762872977770581

- BorakJSliwinskiPPiaseckiZPsychological status of COPD patients on long term oxygen therapyEur Respir J1991459622026240

- EngstromCPPerssonLOLarssonSFunctional status and well being in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with regard to clinical parameters and smoking: a descriptive and comparative studyThorax1996518258308795672

- WhiteRJRudkinSTAshleyJOutpatient pulmonary rehabilitation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ R Coll Physicians Lond1997315415459429193

- BosleyCMCordenZMReesPJPsychological factors associated with use of home nebulized therapy for COPDEur Respir J19969234623508947083

- JonesPWBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPRelationships between general health measured with the sickness impact profile and respiratory symptoms, physiological measures, and mood in patients with chronic airflow limitationAm Rev Respir Dis1989140153815432604285

- KarajgiBRifkinADoddiSThe prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Psychiatry19901472002012301659

- MikkelsenRLMiddelboeTPisingerCAnxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A reviewNord J Psychiatry200458657014985157

- DowsonCAKuijerRGMulderRTAnxiety and self-management behaviour in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what has been learned?Chron Respir Dis2004121322016281648

- HynninenKMBreitveMHWiborgABPsychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a reviewJ Psychosom Res20055942944316310027

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 Suppl43S56S18842932

- SolanoJPGomesBHigginsonIJA comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal diseaseJ Pain Symptom Manage200631586916442483

- FelkerBKatonWHedrickSCThe association between depressive symptoms and health status in patients with chronic pulmonary diseaseGen Hosp Psychiatry200123566111313071

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJDepression and anxiety in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAge Ageing200635545745916638758

- HananiaNAMullerovaHLocantoreNWDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118360461120889909

- CullyJAGrahamDPStanleyMAQuality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety or depressionPsychosomatics20064731231916844889

- PrigatanoGPWrightECLevinDQuality of life and its predictors in patients with mild hypoxemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med19841448161316196380440

- KosmasETselebisABratisDThe Relationship between the adherence to treatment and the psychological profile of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChest20141453_MeetingAbstracts377A

- StapletonRDNielsenELEngelbergRAAssociation of depression and life-sustaining treatment preferences in patients with COPDChest200512732833415654000

- LaurinCMoullecGBaconSLImpact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation riskAm J Respir Crit Care Med201218591892322246177

- FanVSCurtisJRTuSPUsing quality of life to predict hospitalization and mortality in patients with obstructive lung diseasesChest200212242943612171813

- AlmagroPCalboEde EchagüenAOMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest20021211441144812006426

- StageKBMiddelboeTPisingerCDepression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Impact on survivalActa Psychiatr Scand2005111432032315740469

- FanVSRamseySDGiardinoNDSex, depression, and risk of hospitalization and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med20071672345235318039994

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAPA1994

- World Health OrganizationThe ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for ResearchGeneva, SwitzerlandWHO1993

- HamiltonMThe assessment of anxiety states by ratingBr J Med Psychol195932505513638508

- BeckATEpsteinNBrownGSteerRAAn inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric propertiesJ Consult Clin Psychol1988568938973204199

- SpielbergerCDGorsuchRLLusheneRVaggPRJacobsGAManual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y)Palo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologist’s Press1983

- WillgossTGYohannesAMAnxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic reviewRespir Care201358585886622906542

- SmollerJWPollackMHOttoMWPanic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease. Theoretical and clinical considerationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med199615416178680700

- KleinDFFalse suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesisArch Gen Psychiatry1993503063178466392

- DudleyDLGlaserEMJorgensonBNPsychosocial concomitants to rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Part 2: psychosocial treatmentChest19807745445516987045

- KimHFKunikMEMolinariVAFunctional impairment in COPD patients: the impact of anxiety and depressionPsychosomatics20004146547111110109

- PauwelsRABuistASCalverleyPMAGOLD Scientific CommitteeGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med20011631256127611316667

- PattonGCHibbertMRosierMJIs smoking associated with depression and anxiety in teenagers?Am J Public Health1996862252308633740

- BreslauNKilbeyMMAndreskiPNicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adultsAm J Psychiatry19921494644691554030

- AcriJBGrunbergNA psychophysical task to quantify smoking cessation induced irritability: the reactive irritability scale (RIS)Addict Behav1992175876011488939

- ParrottACStress modulation over the day in cigarette smokersAddiction1995902332447703817

- ThorntonALeePFryJDifferences between smokers, ex-smokers, passive smokers and non-smokersJ Clin Epidemiol19944710114311627722548

- UmezawaAA respiratory control method based on psycho-physiological studies Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Advancement of Respiratory Psychophysiology (ISARP), Princeton NJ, October 17–19, 2004Biol Psychiatry200672222238

- O’DonnellDBanzettRCarrieri-KohlmanVPathophysiology of dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a roundtableProc Am Thorac Soc2007414516817494725

- JolleyCJMoxhamJA physiological model of patient-reported breathlessness during daily activities in COPDEur Respir Rev200918112667920956127

- LiottiMBrannanSEganGBrain responses associated with consciousness of breathlessness (air hunger)Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A2001982035204011172071

- EvansKCBanzettRBAdamsLBOLD fMRI identifies limbic, paralimbic, and cerebellar activation during air hungerJ Neurophysiol2002881500151112205170

- LivermoreNButlerJSharpeLMcBainRGandeviaSMcKenzieDPanic attacks and perception of inspiratory resistive loads in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200817871218436789

- BaileyPHThe dyspnea–anxiety–dyspnea cycle – COPD patients’ stories of breathlessness: “It’s scary/when you can’t breathe”Qual Health Res200514676077815200799

- PorzeliusJVestMNochomovitzMRespiratory function, cognitions, and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary patientsBehav Res Ther19923075771540118

- HowardCHallasCWrayJThe relationship between illness perceptions and panic in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBehav Res Ther200947717619027100

- McKenzieDButlerJGandeviaSRespiratory muscle function and activation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Appl Physiol200910762162919390004

- VanderpoolMResilience: a missing link in our understanding of survivalHarv Rev Psychiatry20021030230612202456

- DowsonCATownGIFramptomCPsychopathology and illness beliefs influence COPD self-managementJ Psychosom Res200456333334015046971

- O’DonnellDEWebbKMcGuireMControlling Breathlessness and Cough Comprehensive Management of COPDHamilton, ONBC Decker2002

- LustigFMHaasACastilloRClinical and rehabilitation regime in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasesArch Phys Med Rehabil1972533153224402972

- CantorLJacobsonRCOPD: how to manage comorbid depression and anxietyJ Fam Pract2003211

- BrownGWAndrewsBHarrisTAdlerZBridgeLSocial support, self esteem and depressionPsychol Med19866238247

- HolahanCKHolahanCJSelf-efficacy, social support, and depression in aging: a longitudinal analysisJ Gerontol198742165683794199

- KapteinAAScharlooMFischerMJIllness perceptions and COPD: an emerging field for COPD patient managementJ Asthma20084562562918951252

- TselebisAKosmasEBratisDPrevalence of alexithymia and its association with anxiety and depression in a sample of Greek chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) outpatientsAnn Gen Psychiatry201091620398249

- MishimaMOkuYMuroSRelationship between dyspnoea in daily life and psycho-physiologic state in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during long term domiciliary oxygen therapyIntern Med1996354534588835595

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edWashington, DCAPA2015

- GiftAGMcCroneSHDepression in patients with COPDHeart Lung1993222892978360062

- KoenigHGDifferences between depressed patients with heart failure and those with pulmonary diseaseAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20061421121916505125

- KurosawaHShimizuYNishimatsuYThe relationship between mental disorders and physical severities in patients with acute myocardial infarctionJpn Circ J19834767237286854926

- KatonWSullivanMDDepression and chronic medical illnessJ Clin Psychiatry1990513112189874

- EvansDLStaabJPPetittoJMDepression in the medical setting: biopsychological interactions and treatment considerationsJ Clin Psychiatry199960Suppl 4405510086482

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJPrevalence of sub-threshold depression in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry20031841241612766917

- EmeryCFGreenMRSuhSNeuropsychiatric function in chronic lung disease: the role of pulmonary rehabilitationRespir Care20085391208121618718041

- GraydonJERossEInfluence of symptoms, lung function, mood, and social support on level of functioning of patients with COPDRes Nurs Health19951865255337480853

- WeaverTERichmondTSNarsavageGLAn explanatory model of functional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseNurs Res199746126319024421

- JohnsonGKongDCThomanRFactors associated with medication nonadherence in patients with COPDChest200512853198320416304262

- LeidyNKFunctional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseImage J Nurs Sch199527123347721307

- WagenaEJKantIHuibersMJPsychological distress and depressed mood in employees with asthma, chronic bronchitis or emphysema: a population-based observational study on prevalence and the relationship with smoking cigarettesEur J Epidemiol200419214715315080082

- PostLCollinsCThe poorly coping COPD patient: a psychotherapeutic perspectiveInt J Psychiatry Med19811982112173182

- ClelandJALeeAJHallSAssociations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patientsFam Pract200724321722317504776

- NorwoodRJA review of etiologies of depression in COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20072448549118268923

- SchmidtNBTelchMJJaimezTLBiological challenge manipulation of PCO2 levels: a test of Klein’s (1993) suffocation alarm theory of panicJ Abnorm Psychol199610534464548772015

- FergusonDMComorbidity between depressive disorders and nicotine dependence in a cohort of 16 year oldsArch Gen Psychiatry199653104310478911227

- AgleDPBaumGLPsychological aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Clin North Am1977614749758559893

- DunlopDDLyonsJSManheimLMArthritis and heart disease as risk factors for major depression: the role of functional limitationMed Care200442650251115167318

- CooperCBDetermining the role of exercise in patients with chronic pulmonary diseaseMed Sci Sports Exerc1995271471577723635

- van DijkEJVermeerSEde GrootJCArterial oxygen saturation, COPD, and cerebral small vessel diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20047573373615090569

- CampbellJJ3rdCoffeyCENeuropsychiatric significance of sub-cortical hyperintensityJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci20011326128811449035

- El-AdBLaviePEffect of sleep apnea on cognition and moodInt Rev Psychiatry200517427728216194800

- OzgeCOzgeAUnalOCognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPDBehav Neurol200617212113016873924

- AloiaMSArnedtJTDavisJDNeuropsychological sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: a critical reviewJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20041077278515327723

- FigielGSKrishnanKRDoraiswamyPMSubcortical hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison between late age onset and early onset elderly depressed subjectsNeurobiol Aging1991122452471876230

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J2009331165118519407051

- Nussbaumer-OchsnerYRabeKFSystemic manifestations of COPDChest2011139116517321208876

- EaganTMUelandTWagnerPDSystemic inflammatory markers in COPD: results from the Bergen COPD Cohort StudyEur Respir J20103554054819643942

- AnismanHMeraliZHayleySNeurotransmitter, peptide and cytokine processes in relation to depressive disorder: comorbidity between depression and neurodegenerative disordersProg Neurobiol20088517418346832

- BemtLSchermerTBorHThe risk for depression comorbidity in patients with COPDChest2009135110811118689578

- GiftAGWoodRMCahillCADepression, somatization and steroid use in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Nurs Stud1989262812862767912

- CafarellaPAEffingTWUsmaniZATreatments for anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a literature reviewRespirology201217462763822309179

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceDepression in Adults with a Chronic Physical Health Problem. Treatment and ManagementLondon, UKNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence2009 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91Accessed December 21, 2015

- da Costa SantosCMde Mattos PimentaCANobreMRThe PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence searchRev Lat Am Enfermagem200715350851117653438

- O’ConnorDGreenSHigginsJPTDefining the review question and developing criteria for including studiesHigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.0.0 Updated February 2008London, UKThe Cochrane Collaboration Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/Accessed December 21, 2015

- Critical Appraisal Skills ProgrammeCritical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense Of Evidence. Secondary Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense Of Evidence2013 Available from: http://www.casp-uk.net/Accessed December 21, 2015

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceDepression. The treatment and management of depression in adults This is a partial update of NICE clinical guideline 23. NICE clinical guideline 90102009 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90Accessed January 9, 2016

- YohannesAMManagement of anxiety and depression in patients with COPDExpert Rev Respir Med2008233734720477198

- XuWColletJPShapiroSIndependent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med200817891392018755925

- KoenigHGPredictors of depression outcomes in medical inpatients with chronic pulmonary diseaseAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20061493994817068316

- KunikMERoundyKVeazeyCSurprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disordersChest20051271205121115821196

- CicuttoLCBrooksDSelf-care approaches to managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a provincial surveyRespir Med20061001540154616483758

- CovinoNADirksJFKinsmanRAPatterns of depression in chronic illnessPsychother Psychosom1982371441537178396

- CoffeyCEFigielGSDjangWTLeukoencephalopathy in elderly depressed patients referred for ECTBiol Psychiatry1988241431613390496

- HickieIScottEMitchellPSubcortical hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlates and prognostic significance in patients with severe depressionBiol Psychiatry1995371511607727623

- KrishnanKRHaysJCTuplerLAClinical and phenomenological comparisons of late-onset and early-onset depressionAm J Psychiatry19951527857887726320

- KrishnanKRHaysJCBlazerDGMRI-defined vascular depressionAm J Psychiatry19971544975019090336

- FujikawaTYamawakiSTouhoudaYBackground factors and clinical symptoms of major depression with silent cerebral infarctionStroke1994257988018160223

- CoveyLSGlassmanAHStetnerFMajor depression following smoking cessationAm J Psychiatry199715422632659016279

- CoveyLSTobacco cessation among patients with depressionPrim Care199926369170610436294

- HillasGPerlikosFTsiligianniIManaging comorbidities in COPDInternational Journal of COPD2015109510925609943

- NelsonDRThe cytochrome p450 homepageHum Genomics20094596519951895

- SteenSNThe effects of psychotropic drugs on respirationPharmacol Ther B1976271774113419

- ManGCWHsuKSpouleBJEffect of alprazolam on exercise and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChest1986908328363780329

- HalvorsenTMartinussenPEBenzodiazepine use in COPD: empirical evidence from NorwayInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101695170226356249

- EkströmMPBornefalk-HermanssonAAbernethyAPSafety of benzodiazepines and opioids in very severe respiratory disease: national prospective studyBMJ2014348g44524482539

- BorsonSMcDonaldGJGayleTImprovement in mood, physical symptoms, and function with nortriptyline for depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychosomatics1992331902011557484

- LightRWMerrillEJDesparsJDoxepin treatment of depressed patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med1986146137713803521524

- StrömKBomanGPehrssonKEffect of protriptyline, 10 mg daily, on chronic hypoxaemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J199584254297789488

- GordonGHMichielsTMMahutteCKEffect of desipra-mine on control of ventilation and depression scores in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychiatry Res19851525323925477

- SharmaTNGoyalRLGuptaPRPsychiatric disorders in COPD with special reference to the usefulness of imipramine–diazepam combinationIndian J Chest Dis Allied Sci1988302632683255690

- BorsonSClaypooleKMcDonaldGLDepression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: treatment trialsSemin Clin Neuropsychiatry1998311513010085198

- YohannesAMConnollyMJBaldwinRCA feasibility study of antidepressant drug therapy in depressed elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry20011645145411376459

- EiserNHarteRSpirosKEffect of treating depression on quality-of-life and exercise tolerance in severe COPDCOPD2005223324117136950

- PappLAWeissJRGreenbergHESertraline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety and mood disordersAm J Psychiatry199515215317573598

- SmollerJWPollackMHSystromDSertraline effects on dyspnea in patients with obstructive airways diseasePsychosomatics19983924299538672

- LacasseYBeaudoinLRousseauLRandomized trial of paroxetine in end-stage COPDMonaldi Arch Chest Dis20046114014715679006

- EvansMHammondMWilsonKPlacebo controlled treatment trial of depression in elderly physically ill patientsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry1997128178249283926

- SilvertoothEJDoraiswamyPMClaryGLCitalopram and quality of life in lung transplant recipientsPsychosomatics200445171272

- HegerlUMerglRDepression and suicidality in COPD: understandable reaction or independent disorders?Eur Respir J201444373474324876171

- VoekelMVoelkelNFMacNeeWChronic Obstructive Lung Diseases 2. Psychosocial Aspects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseHamilton, ONB.C. Decker Inc2008

- BrenesGAAnxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatmentPsychosom Med20036596397014645773

- ArgyropoulouPPatakasDKoukouABuspirone effect on breathlessness and exercise performance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration1993602162208265878

- SinghNPDesparsJAStansburyDWEffects of buspirone on anxiety levels and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic airflow obstruction and mild anxietyChest19931038008048449072

- UsmaniZACarsonKVChengJPharmacological interventions for the treatment of anxiety disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Review)Cochrane Database Syst Rev201111CD00848322071851