Abstract

Background

Approximately 30%–60% of adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder (BD) report onset between the ages 15 and 19 years; however, a correct diagnosis is often delayed by several years. Therefore, investigations of the early features of BD are important for adequately understanding the prodromal stages of the illness.

Methods

A complete review of the medical records of 46 children and adolescents who were hospitalized for BD at two psychiatric teaching centers in Prague, Czech Republic was performed. Frequency of BD in all inpatients, age of symptom onset, phenomenology of mood episodes, lifetime psychiatric comorbidity, differences between very-early-onset (<13 years of age) and early-onset patients (13–18 years), and differences between the offspring of parents with and without BD were analyzed.

Results

The sample represents 0.83% of the total number of inpatients (n=5,483) admitted during the study period at both centers. BD often started with depression (56%), followed by hypomania (24%) and mixed episodes (20%). The average age during the first mood episode was 14.9 years (14.6 years for depression and 15.6 years for hypomania). Seven children (15%) experienced their first mood episode before age 13 years (very early onset). Traumatic events, first-degree relatives with mood disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were significantly more frequent in the very-early-onset group vs the early-onset group (13–18 years) (P≤0.05). The offspring of bipolar parents were significantly younger at the onset of the first mood episode (13.2 vs 15.4 years; P=0.02) and when experiencing the first mania compared to the offspring of non-BD parents (14.3 vs 15.9 years; P=0.03). Anxiety disorders, substance abuse, specific learning disabilities, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were the most frequent lifetime comorbid conditions.

Conclusion

Clinicians must be aware of the potential for childhood BD onset in patients who suffer from recurrent depression, who have first-degree relatives with BD, and who have experienced severe psychosocial stressors.

Keywords:

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a lifelong condition that highly impairs functioning and quality of life and increases the risk of a range of psychiatric and somatic comorbidities. For a long time, BD was rarely diagnosed in pediatric populations. However, studies have shown that approximately 30%–60% of individuals diagnosed with BD as adults retrospectively report an onset of illness prior to 20 years of age.Citation1,Citation2 Furthermore, 16%–27% of bipolar adults report that their first mood episode occurred prior to 13 years of age.Citation3

Despite these findings, the diagnosis of BD may be delayed by up to 16 years if the first symptoms occurred in childhood and by 11 years in cases with adolescent onset.Citation1,Citation4 Childhood onset is also associated with a more difficult disease courseCitation5,Citation6 and with several severe conditions, including substance abuse, suicidal behavior, and a greater number of mood episodes.Citation7 Studying the initial stages of BD may therefore improve clinical practices regarding early detection of the illness and avoidance of diagnostic omissions or iatrogenic harm.

Over the past decade, considerable progress has been made in clinical studies of the onset and development of pediatric BD. Large longitudinal studies of bipolar offspring have been conducted worldwide,Citation8–Citation11 and their findings have been incorporated into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), via the inclusion of defined subthreshold syndromes.Citation12

However, many issues remain unresolved. Studies differ regarding the frequency of prepubertal mania (0%Citation9,Citation13 vs 1.2% in preschoolersCitation14), as well as regarding the phenomenology and course of pediatric BD.Citation15,Citation16 While some researchers suggest that the main feature of pediatric mania is chronic irritability,Citation16 others have observed an episodic course with depressive episodes typically preceding the onset of mania.Citation15

Furthermore, we still lack reliable methods of clearly differentiating between unipolar and bipolar depression. The staging model of BD suggests that episodes of minor mood disturbances in late childhood followed by major mood episodes in adolescence precede the onset of mania.Citation17 Therefore, the early detection of depressive pediatric patients who are at risk for mania is of high clinical importance because it may lead to tailored treatment and prevent iatrogenic harm. Several clinical predictors have been identified in adults, including rapid onset of depressive symptoms, psychomotor retardation, mood-congruent psychotic features, family history of BD, and history of pharmacologically induced hypomania.Citation18 However, few studies evaluating pediatric populations have been published. Conduct disorders, multigenerational family history of BD, subthreshold BD symptoms, and baseline deficits in emotional regulation have been identified.Citation19–Citation21 In addition to these clinical parameters, neuroimaging has also been tested as a potentially objective method for the differential diagnosis of unipolar vs bipolar conditions. In an extensive review, Serafini et al found that reduced corpus callosum volume and increased rates of deep white matter hyperintensities were specific findings for pediatric BD;Citation22 however, these neurobiological findings are far from being employed in regular clinical evaluations. Clinical research therefore represents an irreplaceable approach in improving diagnostics and treatment.

Surprising differences in BD prevalence in clinical samples have been described in recent reports. Differences among European countries are notably smaller than differences between Europe and the US. For example, in Germany, researchers found a 0.27% frequency of BD,Citation23 whereas in Denmark, a 1.2% frequency was found.Citation24 In Finland, the frequency was 1.7%.Citation25 Conversely, in the US, 10% of child inpatients and 10% of adolescents were reported to have BD in 1994, compared to 36% and 26%, respectively, in 2004.Citation26 The above-detailed discrepancies in published results and ongoing debates regarding BD presentation in pediatric populations motivated us to perform a retrospective analysis of an inpatient sample of children and adolescents from two leading centers of child psychiatry in the Czech Republic.

In all evaluated inpatients, we aimed to establish BD frequency, age of symptom onset, phenomenology of mood episodes, and lifetime psychiatric comorbidity. Furthermore, we analyzed differences between very-early-onset (<13 years of age) and early-onset (13–18 years) patients, as well as differences between offspring from parents with and without BD. Finally, we assessed whether boys and girls differ in age of onset and lifetime comorbidity.

Methods

Sample

The current sample included children and adolescents who were hospitalized for BD at two sites: the Department of Child Psychiatry at Motol University Hospital (during the years 1997–2014; n=4,515) and the Children’s Department of the Bohnice Psychiatric Hospital (during the years 2010–2014; n=968), both in Prague, Czech Republic.

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were employed: age <18 years and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)-based diagnosis of BD. We included all subjects with BD, regardless of the severity of the disorder or the presence of other psychiatric comorbidities (excluding dependencies). Diagnosis was established using a semi-structured clinical interview for mental disorders developed via institutional consensus at both centers and confirmed by the Board of Senior Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists, including the medical director of the Department of Child Psychiatry at Motol University Hospital and Children’s Department at the Psychiatric Hospital Bohnice. However, this interview was not validated, and there is no national-language version of the clinical interviews that have been used in some other studies (eg, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and LifetimeCitation27). The raters of this study reviewed all diagnoses according to the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).Citation28

Exclusion criteria

The only exclusion criterion was diagnosis of a mood disorder due to a medical condition or substance abuse.

Procedure

Two experienced child and adolescent psychiatrists performed a review of all entries of medical records of children and adolescents hospitalized for BD. Demographic data, family history of psychiatric illness, psychiatric diagnoses or symptoms preceding the onset of a typical mood episode, and Axis I comorbidities were collected. Stressors that are routinely evaluated in the Department of Child Psychiatry at Motol University Hospital and Children’s department at the Psychiatric Hospital Bohnice based on psychiatric interviews were included in the analysis. These included death of a beloved parent, childhood abuse or neglect, and severe bullying. The Young Mania Rating Scale and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were used to rate mood and anxiety symptoms based on chart entries. Very-early-onset BD was defined as an onset of the first mood episode before the age of 13 years.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R statistical software. Two-sample Welch’s t-tests with approximate degrees of freedomCitation29 were used to compare mean ages between sexes, age-of-onset groups, and BD- and non-BD-offspring groups (the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test normality assumptions). Associations between sex and categorical variables, as well as between age of onset and categorical variables, were investigated using Fisher’s exact test. All analyses were tested at a significance level of 0.05.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Motol University Hospital. The participants’ parents provided informed written consent for analysis and publishing of clinical data collected during the hospitalization of their children.

Results

A total of 46 children and adolescents, of whom 21 (47%) were girls, met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BD. This sample represents 0.82% (Motol department) and 0.84% (Bohnice department) of the total number of child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients (n=5,483) admitted during the study period at each center. In many of the patients, BD started with depression (56%), followed by hypomania (24%) and mixed episodes (20%). The average age at the first mood episode was 14.9 years (14.6 years for depression and 15.6 years for hypomania) (for details, ). The sociodemographic characteristics of our sample are shown in .

Table 1 Age characteristics of the total sample and of the subgroups with very-early-onset (<13 years) and early-onset (13–18 years) BD

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics

The majority of the patients (n=37; 80%) initially underwent psychiatric treatment for a condition other than BD. The most frequent initial conditions that were diagnosed included major unipolar depression (n=11; 24%), acute psychosis (n=9; 20%), mixed/manic episode respectively BD (n=9; 20%), adjustment disorder (n=6; 13%), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) (n=3; 7%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (n=2; 4%), anorexia nervosa (n=2; 4%), anxiety disorder (n=2; 4%), conduct disorder (n=1; 2%), and unspecified personality disorder (n=1; 2%).

Anxiety disorders (30%), substance abuse (26%), specific learning disabilities (19%), and ADHD (15%) were the most frequent lifetime comorbid conditions. Multiple lifetime comorbidities were present in 15 patients (33%). The lifetime comorbidity data are summarized in .

Table 3 Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity with bipolar disorder

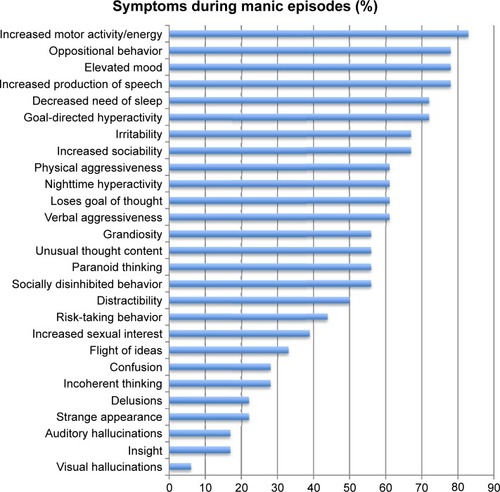

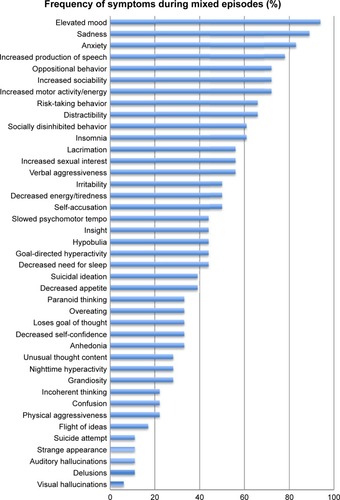

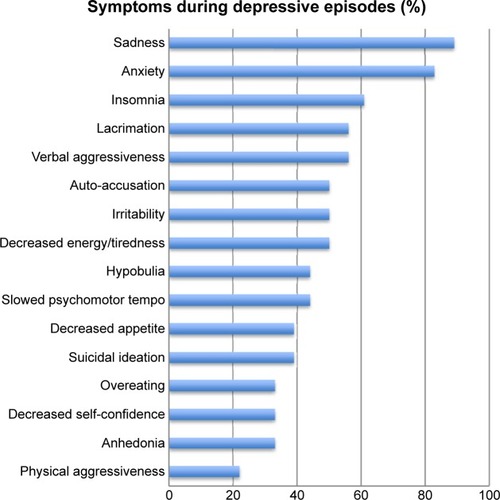

The phenomenology of the episodes that occurred during hospitalization and their associated features are shown in and –. In comparing manic symptoms between manic and mixed episodes, no significant differences in frequency were identified, with the exception of physical aggressiveness (61% in manic episodes vs 21% in mixed episodes; P=0.04). No differences were found when comparing depressive symptoms between mixed and depressive episodes.

Figure 1 Frequency of symptoms during manic episodes in pediatric inpatients with bipolar disorder, n=16.

Figure 2 Frequency of symptoms during mixed episodes in pediatric inpatients with bipolar disorder, n=18.

Figure 3 Frequency of symptoms during depressive episodes in pediatric inpatients with bipolar disorder, n=7.

Table 4 Bipolar disorder subtypes and features of current episodes

Comparison of very-early-onset vs early-onset groups

Seven children (15%) experienced their first mood episode before 13 years of age (three boys, four girls). The age characteristics of both groups related to psychiatric medical history are shown in .

The very-early-onset group had a significantly longer delay between age at first mood episode and age at diagnosis of BD (1.9±1.4 years vs 0.7±0.7 years; P=0.046). The difference in the delay between age at first depression and age at first mania between the groups was not significant (2.0±1.2 years vs 0.9±0.8 years; P=0.06).

Comparisons of the clinical variables between the groups revealed that the very-early-onset group more frequently experienced traumatic events (P=0.03), more frequently experienced ADHD as a first psychiatric diagnosis (P=0.02), and were more likely to have a first-degree relative with a mood disorder (P=0.02) compared to the adolescent-onset group (for details, ).

Table 5 Comparison of clinical characteristics between very-early-onset (<13 years) and early-onset (13–18 years) bipolar disorder patients

Comparison of offspring from parents with and without BD

One-third of our patients (n=14; 30%) had a first-degree relative suffering from a mood disorder. Eight patients (17%) had a parent with BD. The offspring of a bipolar parent or parents had significantly earlier ages of BD onset (13.2 vs 15.4 years; P=0.03) and earlier onset of mania (14.3 vs 15.9 years; P=0.03) compared to the offspring of parents without BD; however, there were no differences in age of depression onset (13.3 vs 15.0 years; P=0.12). Furthermore, the groups differed regarding the age at first psychiatric contact (13.1 vs 15.2 years; P=0.045), and there was a trend toward earlier age at initial BD diagnosis (14.7 vs 16.1 years; P=0.053) ().

Table 6 Comparison of age characteristics between offspring from bipolar parents (BD parent) and those of patients without family histories of BD (non-BD parent)

Sex differences

We found that boys had a significantly greater number of neurodevelopmental lifetime diagnoses (ADHD and/or learning disabilities) than girls (n=10 [40%] vs n=2 [10%]; P=0.04), while girls had a greater number of eating disorders (n=0 vs n=4; 19%; P=0.04) and higher frequency of alcohol abuse (n=0 vs n=4; 19%; P=0.04). No significant sex-related differences were established for age at onset of mood episodes, mood episode features, family history, or other characteristics (for details, ).

Table 7 Comparison of age characteristics between boys and girls

Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to describe the early features and development of BD by analyzing data corresponding to an inpatient sample of adolescents diagnosed with BD.

The prevalence of BD diagnosis in children and adolescents hospitalized with other diagnoses was 0.83% at both study centers, which is similar to results from a study conducted in Denmark (1.2%).Citation24 However, these findings differ greatly from a similar study in the US, where the prevalence of BD in children and adolescents discharged from inpatient units was 10% in 1996 and 36% in 2004.Citation26 Additionally, in retrospective studies, the rates of childhood-onset BD differ between Europe and the US. Post et al found that childhood- or adolescent-onset bipolar illness was reported by 61% of those in a US cohort but only by 30% of those in a cohort including participants from the Netherlands and Germany.Citation30,Citation31 The higher rate reported in the US cohort may be due to expanded diagnostic criteria or to diagnosis of BD in children with chronic irritability, which was not previously considered a BD symptom. However, it may also reflect environmental and genetic factors. Post et al found that the substantially higher incidence of childhood-onset BD in the US sample was accompanied by a twofold-higher frequency of positive family history of BD compared to that in the European samples.Citation30,Citation31

The influence of family history of affective disorders on age at BD onset was recently reported.Citation7 In an extensive review, it was found that a childhood-onset group, but not an adolescent-onset group, had significantly higher rates of first-degree relatives with mood disorders than an adult-onset group.Citation7 Similarly, Post et al found that an early age at BP onset was associated with increased parental history of affective disorder.Citation31 We have replicated this finding in our study. Furthermore, we found that offspring of bipolar parents had significantly earlier average ages of first mood episode (13.2 vs 15.4 years) and mania (14.3 vs 15.9 years) than did offspring of non-bipolar parents.

In addition to these genetic factors, it has also been suggested that psychosocial stressors might not only affect the course of BD but also the age at BD onset.Citation32 In addition to stressors such as sexual abuse, neglect, and death of a beloved parent, we included peer bullying, as this is a severe stressor that has been associated with increased risk of a wide range of psychopathologies.Citation33 We found that severe traumatic events were significantly more likely to be present in the medical histories of the very-early-onset group than in those of the early-onset group. This finding corresponds to a recent study that demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between age at onset and number of traumatic events experienced.Citation34 However, several other stressors that were not evaluated in our study (eg, family stress) have been indicated to be involved in the course of BD, especially in its initial stages.Citation18

Manic episode frequency during childhood is another matter of discussion. Since the creation of Kraepelin’s classification, it has been agreed that manic episodes may occur at prepubertal ages; however, for decades, this phenomenon was considered rare.Citation35 In recent studies, several authors have suggested that mania is not uncommon in child and adolescent populations.Citation14,Citation36 Birmaher et al in a study of high-risk offspring found hypo/mania in 9.7% of children with bipolar disorder less than 12 years of age and the diagnosis of BD not otherwise specified was established in 46% of children with bipolar disorder before they reached 12 years of age.Citation10 Our current data correspond with the more classic view. We found only one case (2%) of mania occurring before 12 years of age (an 11.5-year-old boy with comorbid autism spectrum disorder) and three cases before 13 years of age (6%).

In a mixed inpatient and outpatient sample of pediatric bipolar patients, Lázaro et al analyzed differences in diagnostic delays between a group with BD onset before 13 years of age and a group with later onset.Citation36 They found that the former group differed significantly from the latter (1.2 vs 0.8 years).Citation36 Our results are concordant with their findings (1.9 vs 0.7 years). The delay in diagnosing BD in our group is attributable to the delay between first depression and first mania (2 years).

In the majority of our patients (56%), bipolar illness started with depression. This is similar to findings from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), in which 63.5% of first mood episodes were depressive in a very-early-onset (<13 years) group and 58.7% were depressive in an early-onset group (13–18 years).Citation3 However, it must be noted that some patients may experience a very brief early hypomanic episode but cycle heavily on the depressive pole later on.Citation37 Nevertheless, prospective studies support the notion that, in most cases, BD starts with several depressive episodes before mood elevation. Duffy et al found that 97% of high-risk subjects who developed BD experienced a first mood episode that was either minor or major depression,Citation15 and Hillegers et al reported that 91% of subjects had depression at onset.Citation9

The most common comorbid conditions in our sample were anxiety disorders. This corresponds with findings from a representative high-risk-offspring study.Citation13 Additionally, higher rates of anxiety disorders have been reported in studies such as STEP-BD, where anxiety disorders were present in 54%–69% of patients.Citation3 The presence of anxiety disorders was found to be a strong risk factor for later onset of BD.Citation13

We found that 19% of patients in our sample also suffered from OCD in their lifetime. This finding corresponds with those from STEP-BD, where BD and OCD comorbidity was found in 13.5% of patients <13 years old at onset and in 8.7% of a 13- to 18-year-old onset group.Citation3 Both epidemiological and clinical studies have reported that OCD and BD coexist in 11%–21% of adults.Citation38

The prevalence of ADHD (28%) as a comorbidity in our sample corresponds with findings from other studies of the phenomenology of pediatric BD (21%,Citation39 38%Citation40). However, the relationship between BD and ADHD is still unclear. Duffy reviewed the nature of this relationship in findings from prospectively assessed high-risk-offspring studies.Citation41 She concluded that a clinical diagnosis of childhood ADHD is not a reliable predictor of the development of BD; rather, the symptom of inattention may be part of a mixed clinical presentation during the early stages of evolving BD, appearing alongside anxiety and depressive symptoms.Citation41 Conversely, an analysis of 61,187 individuals with ADHD who were included in a Swedish longitudinal national register found that subjects diagnosed with ADHD were 24 times more likely to be diagnosed with BD in adulthood compared with those in a control group.Citation42 Furthermore, first-degree relatives of subjects with ADHD were more likely to have been diagnosed with BD than first-degree relatives of control group participants, suggesting the existence of shared genetic factors between these disorders.Citation42 This finding does not necessarily conflict with the conclusions of Duffy’s review.Citation41 Although ADHD is categorically defined, there is also evidence supporting the notion that ADHD is an extreme presentation of a continuous trait.Citation43 Thus, the inattention symptoms that were present in the studies reviewed by Duffy may be part of a genetic and etiologic continuum of ADHD that was also identified in other offspring studies.Citation44,Citation45

In comparing differences between the sexes regarding symptoms and comorbidity, we found that boys had a greater number of neurodevelopmental lifetime comorbidities, including ADHD (respectively hyperkinetic disorder of activity and attention and hyperkinetic conduct disorder with disruptive symptoms and irritability) and learning disabilities, compared to girls. Although a previous study did not find significant differences between boys and girls in the manifestation of BD,Citation46 our current results correspond with the findings of several high-risk-offspring studies in which a greater number of disruptive symptoms were found in boys than in girls.Citation47,Citation48 Therefore, it is unclear whether irritability as a hallmark symptom of pediatric BD may be generalized to the entire pediatric population or whether it is specific to bipolar boys with a high comorbidity of ADHD and/or oppositional defiant disorder.

Limitations

The current study possessed several limitations that must be taken into consideration. Our data on patient medical history are based on retrospective reports by patients, parents, and previous medical charts. This may lead to the omission of subthreshold manifestations of mental disorders. Although institutional consensus-based, semi-structured clinical interviews were used, these were not validated. Furthermore, the included patients were not followed up; therefore, the possibility that their diagnoses were eventually changed to reflect an alternative condition cannot be excluded. Finally, we only enrolled patients with diagnosed hypomania. Therefore, bipolar patients who had already been treated for depression but did not experience an onset of first mania until after the age of 18 years were not captured by our methodology.

Conclusion

Compared to studies conducted in the US, we found a lower prevalence of BD among children and adolescent psychiatric inpatients. In the majority of our sample, the first episode of mania occurred during adolescence. However, clinicians must be highly aware of the possibility of BD onset during childhood in patients who suffer from early depression, have a first-degree relative with BD, or who have experienced severe psychosocial stressors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant IGA (Internal Grant Agency of the Czech Ministry of Health) NT 13337–4/2012, and by the project (Ministry of Health, Czech Republic) for conceptual development of research organization 00064203 (University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic). Part of the study was presented at the 60th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 22–27, 2013; Orlando, FL, USA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EgelandJAHostetterAMPaulsDLSussexJNProdromal symptoms before onset of manic-depressive disorder suggested by first hospital admission historiesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039101245125211026178

- MorselliPLElgieRGAMIAN-EuropeGAMIAN-Europe/BEAM survey I – global analysis of a patient questionnaire circulated to 3450 members of 12 European advocacy groups operating in the field of mood disordersBipolar Disord20035426527812895204

- PerlisRHMiyaharaSMarangellLBSTEP-BD InvestigatorsLong-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD)Biol Psychiatry200455987588115110730

- LeboyerMHenryCPaillere-MartinotMLBellivierFAge at onset in bipolar affective disorders: a reviewBipolar Disord20057211111815762851

- CarlsonGABrometEJDriessensCMojtabaiRSchwartzJEAge at onset, childhood psychopathology, and 2-year outcome in psychotic bipolar disorderAm J Psychiatry2002159230730911823277

- LeverichGSPostRMKeckPEJrThe poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorderJ Pediatr2007150548549017452221

- HoltzmanJNMillerSHooshmandFChildhood-compared to adolescent-onset bipolar disorder has more statistically significant clinical correlatesJ Affect Disord201517911412025863906

- DuffyAAldaMCrawfordLMilinRGrofPThe early manifestations of bipolar disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parentsBipolar Disord20079882883818076532

- HillegersMHReichartCGWalsMVerhulstFCOrmelJNolenWAFive-year prospective outcome of psychopathology in the adolescent offspring of bipolar parentsBipolar Disord20057434435016026487

- BirmaherBAxelsonDMonkKLifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring studyArch Gen Psychiatry200966328729619255378

- EgelandJAEndicottJHostetterAMAllenCRPaulsDLShawJAA 16-year prospective study of prodromal features prior to BPI onset in well Amish childrenJ Affect Disord20121421–318619222771141

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth EditionWashingtonAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- DuffyAAldaMHajekTGrofPEarly course of bipolar disorder in high-risk offspring: prospective studyBr J Psychiatry2009195545745819880938

- BirmaherBAxelsonDGoldsteinBPsychiatric disorders in preschool offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS)Am J Psychiatry2014167332133020080982

- DuffyAAldaMHajekTSherrySBGrofPEarly stages in the development of bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord20101211–212713519541368

- BiedermanJFaraoneSWozniakJMickEKwonAAleardiMFurther evidence of unique developmental phenotypic correlates of pediatric bipolar disorder: findings from a large sample of clinically referred preadolescent children assessed over the last 7 yearsJ Affect Disord200482Suppl 1S45S5815571789

- DuffyAHorrocksJDoucetteSKeown-StonemanCMcCloskeySGrofPThe developmental trajectory of bipolar disorderBr J Psychiatry2014204212212824262817

- GoodwinFKJamisonKRManic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression2nd edNew YorkOxford University Press2007

- StroberMLampertCSchmidtSMorrellWThe course of major depressive disorder in adolescents: I. Recovery and risk of manic switching in a follow-up of psychotic and nonpsychotic subtypesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry199332134428428882

- GellerBFoxLWClarkKARate and predictors of prepubertal bipolarity during follow-up of 6- to 12-year-old depressed childrenJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19943344614688005898

- BiedermanJWozniakJTarkoLRe-examining the risk for switch from unipolar to bipolar major depressive disorder in youth with ADHD: a long term prospective longitudinal controlled studyJ Affect Disord2014152–154347351

- SerafiniGPompiliMBorgwardtSBrain changes in early-onset bipolar and unipolar depressive disorders: a systematic review in children and adolescentsEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201423111023104125212880

- HoltmannMDuketisEPoustkaLZepfFDPoustkaFBölteSBipolar disorder in children and adolescents in Germany: national trends in the rates of inpatients, 2000–2007Bipolar Disord201012215516320402708

- ThomsenPHMøllerLLDehlholmBBraskBHManic-depressive psychosis in children younger than 15 years: a register-based investigation of 39 cases in DenmarkActa Psychiatr Scand19928554014061605062

- SouranderACombined psychopharmacological treatment among child and adolescent inpatients in FinlandEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200413317918415254846

- BladerJCCarlsonGAIncreased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among U.S. child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004Biol Psychiatry200762210711417306773

- KaufmanJBirmaherBBrentDSchedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity dataJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1997369809889204677

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text RevisionAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- RaschDTeuscherFGuiardVHow robust are tests for two independent samples?J Stat Plan Inference2007137827062720

- PostRMLuckenbaughDALeverichGSIncidence of childhood-onset bipolar illness in the USA and EuropeBr J Psychiatry2008192215015118245035

- PostRMLeverichGSKupkaRIncreased parental history of bipolar disorder in the United States: association with early age of onsetActa Psychiatr Scand2014129537538224138298

- PostRMLeverichGSThe role of psychosocial stress in the onset and progression of bipolar disorder and its comorbidities: the need for earlier and alternative modes of therapeutic interventionDev Psychopathol20061841181121117064434

- KimJWLeeKLeeYSFactors associated with group bullying and psychopathology in elementary school students using child-welfare facilitiesNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20151199199825897236

- AnandAKollerDLLawsonWBGershonESNurnbergerJIBiGS CollaborativeGenetic and childhood trauma interaction effect on age of onset in bipolar disorder: an exploratory analysisJ Affect Disord20151791525837715

- CarlsonGAGlovinskyIThe concept of bipolar disorder in children: a history of the bipolar controversyChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am200918225727119264263

- LázaroLCastro-FornielesJde la FuenteJEBaezaIMorerAPàmiasMDifferences between prepubertal- versus adolescent- onset bipolar disorder in a Spanish clinical sampleEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200716851051617846818

- HinzMSteinAUnciniTA pilot study differentiating recurrent major depression from bipolar disorder cycling on the depressive poleNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2010674174721173882

- AmerioAOdoneALiapisCCGhaemiSNDiagnostic validity of comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic reviewActa Psychiatr Scand2014129534335824506190

- SoutulloCAChangKDDíez-SuárezABipolar disorder in children and adolescents: international perspective on epidemiology and phenomenologyBipolar Disord20057649750616403175

- MasiGPerugiGMillepiediSDevelopmental differences according to age at onset in juvenile bipolar disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200616667968517201612

- DuffyAThe nature of the association between childhood ADHD and the development of bipolar disorder: a review of prospective high-risk studiesAm J Psychiatry2012169121247125523212056

- LarssonHRydénEBomanMLångströmNLichtensteinPLandénMRisk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in relatives of people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorderBr J Psychiatry2013203210310623703314

- LarssonHAnckarsaterHRåstamMChangZLichtensteinPChildhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as an extreme of a continuous trait: a quantitative genetic study of 8,500 twin pairsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry2012531738021923806

- ChangKDSteinerHKetterTAPsychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspringJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039445346010761347

- SinghMKDelBelloMPStanfordKEPsychopathology in children of bipolar parentsJ Affect Disord20071021–313113617275096

- BiedermanJKwonAWozniakJAbsence of gender differences in pediatric bipolar disorder: findings from a large sample of referred youthJ Affect Disord2004832–320721415555715

- Radke-YarrowMNottelmannEMartinezPFoxMBBelmontBYoung children of affectively ill parents: a longitudinal study of psychosocial developmentJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry199231168771537784

- WalsMHillegersMHReichartCGOrmelJNolenWAVerhulstFCPrevalence of psychopathology in children of a bipolar parentJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20014091094110211556634