Abstract

Objective

When considering repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for major depressive disorder, clinicians often face a lack of detailed information on potential interactions between rTMS and pharmacotherapy. This is particularly relevant to patients receiving bupropion, a commonly prescribed antidepressant with lower risk of sexual side effects or weight increase, which has been associated with increased risk of seizure in particular populations. Our aim was to systematically review the information on seizures occurred with rTMS to identify the potential risk factors with attention to concurrent medications, particularly bupropion.

Data sources

We conducted a systematic review through the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and EMBASE between 1980 and June 2015. Additional articles were found using reference lists of relevant articles. Reporting of data follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened articles reporting the occurrence of seizures during rTMS. Articles reporting seizures in epilepsy during rTMS were excluded. A total of 25 rTMS-induced seizures were included in the final review.

Data extraction

Data were systematically extracted, and the authors of the applicable studies were contacted when appropriate to provide more detail about the seizure incidents.

Results

Twenty-five seizures were identified. Potential risk factors emerged such as sleep deprivation, polypharmacy, and neurological insult. High-frequency-rTMS was involved in a percentage of the seizures. None of these seizures reported had patients taking bupropion in the literature review. One rTMS-induced seizure was reported from the Food and Drug Administration in a sleep-deprived patient who was concurrently taking bupropion, sertraline, and amphetamine.

Conclusion

During the consent process, potential risk factors for an rTMS-induced seizure should be carefully screened for and discussed. Data do not support considering concurrent bupropion treatment as contraindication to undergo rTMS.

Background

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a noninvasive neurostimulation treatment that is evolving toward a mainstream therapeutic option for major depression.Citation1 rTMS can be used in monotherapy as well as in combination with antidepressant medications, particularly when facing treatment-resistant depression.Citation2 In this regard, during the assessment and consent process, clinicians and patients still face important questions with regard to the interaction of pharmacological interventions with rTMS, specifically in terms of safety of the combined intervention. When discussing medications and potential hazards for rTMS, current guidelines on use of rTMS establish a categorization of medications that can pose a potential hazard for rTMS.Citation3 Under category 1, there are compounds listed which state that the intake of one or a combination of the following drugs forms a strong potential hazard for application of rTMS due to their significant seizure threshold-lowering potential. Thus, a recommendation is made that rTMS should be performed, when required, with particular caution. Tricyclic antidepressants, some antipsychotics, and stimulants are included. However, other antidepressants, mostly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and bupropion as well, are listed under category 2 and categorized as posing a relative hazard for the application of rTMS, and the recommendation is to perform rTMS, when required, with caution.Citation3

Nonetheless, cases in which patients are on bupropion and are referred for consideration of rTMS can raise legitimate questions during the assessment and consent process in clinicians and patients alike with regard to the safety of such combined treatment. Although bupropion is classified in category 2 with other SSRI or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), such as fluoxetine or venlafaxine,Citation3 the perception of risk with regard to the combination of rTMS–bupropion might have suffered from a similar situation to that in eating disorders whereby a culture of considering all formulations of bupropion as an absolute contraindication seemed to permeate into clinical practice.Citation4

Despite more recent evidence suggesting that extended-release (XR) formulations of bupropion may not pose any higher seizure risk than other antidepressants, clinicians often remain reluctant to prescribe bupropion in the setting of eating disorders.Citation4 A similar reluctance may also persist in some clinicians regarding the use of rTMS in patients taking bupropion. In order to provide with accurate and current information on the topic, we wanted to provide clinicians with a systematic review of the literature on the occurrence of rTMS-induced seizures with a special focus on the role of concurrent medications, including bupropion. The ultimate goal is to provide clinicians and patients alike with a detailed review of the topic in order to aid in informing the consent process of patients who are on bupropion and are contemplating a course of rTMS.

Pharmacodynamic profile of bupropion and risk of seizure

Bupropion is a commonly prescribed noradrenaline–dopamine reuptake inhibitor antidepressant indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder as well as an aid in smoking cessation. In depression, it can be used on monotherapy or as an add-on medication for patients with an insufficient response to first-line SSRI antidepressants.Citation5,Citation6 First released in the United States market in 1985 (1998 in Canada), it is currently available in three oral formulations that have bioequivalent systemic exposure to bupropion, in both rate and extent of absorption.Citation7 The first oral formulation is an immediate release (IR) formulation and is administered three times per day; the second is sustained release (SR) and is administered twice per day; the third is extended/modified release administered once per day. Primarily, bupropion acts as a dopamine–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist.Citation8 This unique pharmacodynamic profile differentiates bupropion from other antidepressants and results in lower rates of side effects such as sexual dysfunction, somnolence, or weight gain that are prevalent in SSRIs and SNRIs.Citation9–Citation12 The differential side-effect profile of bupropion compared to other antidepressant medications might contribute some patients to prefer bupropion over other antidepressant medicationsCitation13 or clinicians to consider bupropion as a first alternative when patients cannot tolerate side effects associated to SSRIs or SNRIs.Citation14

The most common side effects of bupropion (SR, 300–400 mg) compared to placebo include headache (25%–26% vs 23%), dry mouth (17%–24% vs 7%), and nausea (13%–18% vs 8%).Citation12 Seizures are the most serious side effects associated with bupropion, with a 0.4% risk of seizure when taking bupropion IR at 300–450 mg/d. Due in part to this higher risk, the IR formulation of bupropion has been discontinued in many jurisdictions of the United States and Canada, in favor of slower-release formulations carrying a lower risk of seizure induction.

There is a dose–response effect in the association of seizures with bupropion: the higher the dose of bupropion, the higher the risk of seizures. For example, the risk of seizure increases from 0.1% to 0.4% when taking bupropion SR 100–300 mg/d to 400 mg/d, respectively.Citation12 When bupropion was first introduced in the United States in 1985, the recommended dosage was 400–600 mg/d. Immediately upon introduction, a study conducted resulted in bupropion being temporarily withdrawn from the market between 1986 and 1989.Citation15 Horne et alCitation15 conducted a double-blind placebo-controlled study on eating disorders patients (bulimia) and bupropion. After four out of 55 participants taking bupropion experienced grand-mal seizures, the high frequency (HF) of seizures in the study was alarming and bupropion was temporarily suspended. Postmarketing research showed that the incidence of seizure rates was directly proportional to both dosing and type of oral formulation used. Specifically, the higher the dose, the higher the risk of seizures, and IR formulations carry a higher risk compared to SR or XR formulations. In addition, seizure risk was found to be associated with patient factors, clinical situations, and concomitant medications. As a result of new data, modifications to the medication information sheet were made regarding reduction of dosing as well as additional contraindications such as history of head trauma or prior seizure, brain tumor, severe hepatic cirrhosis, concomitant medications that lower seizure threshold, excessive use of alcohol or sedatives (including benzodiazepines), drug addictions, and diabetes.Citation12

rTMS and risk of seizure

rTMS was approved for the treatment of depression in Canada (2002) and in the United States (2008) and has been used to effectively treat thousands of patients with depression. The rTMS treatment protocol is noninvasive and capitalizes on the principle of electromagnetic induction to elicit an electrical current in brain tissue of enough magnitude to depolarize neurons within the cerebral cortex; these neurons are part of relevant circuits involved in emotional regulation.Citation16 The most common side effects include headache (5%–23%) and discomfort at the site of stimulation (20%–40%).Citation17–Citation22 The most serious side effect associated with rTMS is the accidental induction of a seizure. Although accidental seizures occur at a frequency of <0.1%, there are factors that may increase the risk of rTMS triggering a seizure such as sleep deprivation, family history of seizures, alcohol use, and previous neurological condition.Citation20,Citation23

Methods

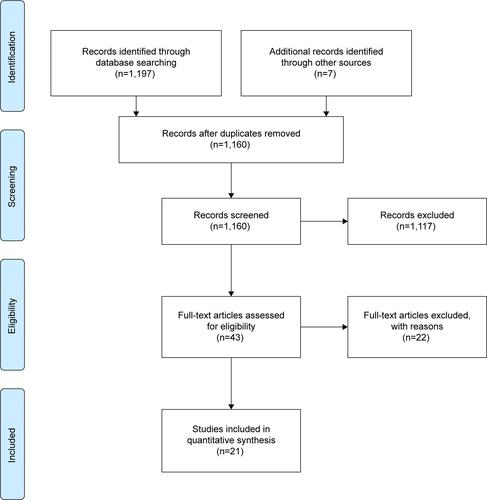

We conducted a systematic review of rTMS-related accidental seizures. Inclusion criteria were 1) case reports or case series or studies, where the occurrence of a seizure was reported, 2) using rTMS or TMS, 3) any language, 4) any age, and 5) studies on humans. Exclusion criteria were 1) rTMS/TMS studies in samples afflicted by epilepsy, 2) not enough information to establish that a seizure had occurred, and 3) reports of non-seizure side effects. A total of 1,197 records were identified through the databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and EMBASE with the search terms “rTMS” or “TMS” or “transcranial magnetic stimulation” or “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation” and “ictal activity” or “seizure” or “convulsion” or “epilepsy” or “epileptic” (detailed information is given in ). The search was conducted in between June 6 and 10, 2015, and included papers in all languages since the year 1980. An additional seven records were identified through other sources, namely references from original records. All records were initially screened, and 1,154 were excluded due to the following reasons: investigated epilepsy and/or chronic seizure patients, was a review paper, unrelated to the topic, used animal subjects, had no seizures induced, or was a duplicate record. Following the initial screening, 43 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Out of the 43 assessments, 22 articles were excluded, as four reported rTMS-induced syncope, 13 were comments/reviews on rTMS, one used an H-coil for deep rTMS, three did not induce a seizure, and one article investigated an epilepsy patient. Therefore, 21 articles that reported 25 rTMS-induced seizures were included in the final literature review.Citation23–Citation42 Two raters conducted the search and went through the selection process and reviewed the full-text papers. Another investigator independently rated the 43 full-text articles selected to confirm that the final articles were properly selected based on the criteria.

Authors were contacted for further information regarding missing information in the 25 seizure reports. Those contacted include A Chervyakov, K Brogmus, E Wassermann, M Rosa, and R Kandler. Additional information extracted pertained to the paper by Kandler, dictated that the stimulation would have been using a large coil placed at the vertex to stimulate the small hand and foot muscles, and that the frequency of the stimuli would have been no more than 0.3 Hz (–RH Kandler, Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, electronic communication, February 6, 2014). Chervyakov et alCitation42 also described the two seizures reporting their stroke location (left and right middle cerebral artery basin), the rTMS session that the seizures occurred (single pulse during diagnostic mapping, 1st session of high frequency rTMS), also that both seizures were associated with underestimation of the EEG data during screening (A Chervyakov, electronic communication, June 15, 2015, Research center of neurology, Russian Academy of Medical Science, Moscow, Russia).

Results

Our systematic review yielded 25 reports of rTMS-induced seizures; 23 reports were from peer-reviewed journals and two were from conference abstracts. All data included fulfilled our inclusion criteria (). Case series are summarized in (detailed information is given in ). There was 15 women, nine men, and one unknown reported to have experienced TMS-induced seizures. Women were significantly younger than men with women’s having a mean age of 31 vs men’s mean age of 49 years old (independent t-test; P>0.005, two-tailed). In terms of diagnoses, nine were receiving rTMS in the context of a depressive episode, nine for neurological conditions, six were healthy volunteers, and one had a pain syndrome.

Table 1 Summary table of rTMS induced accidental seizures including the author, type of TMS, location, medications, risk factors, type of seizure, and diagnosis

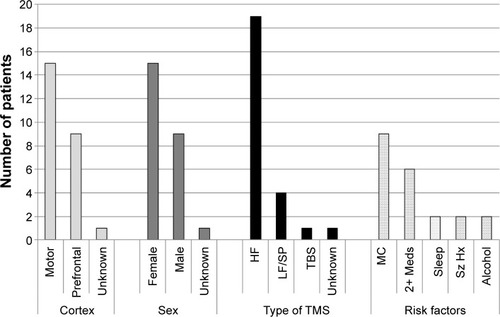

Details on TMS parameters are provided in and summarized in . Briefly, 19 cases had HF-rTMS (>3 Hz),Citation23–Citation34,Citation42 four cases with multiple single-pulse stimulations,Citation23,Citation35–Citation38,Citation42 one continuous theta-burst stimulation (cTBS),Citation39 and one not reported.Citation40 Fifteen reports were cases where motor cortex was stimulated,Citation23,Citation28,Citation29,Citation32,Citation35–Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 nine where prefrontal cortex was stimulated,Citation24–Citation27,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation34 and one not reported.Citation40 The intensity of stimulation used is very heterogeneous and ranges from 40% to 130% resting motor threshold (RMT). Of note, there were no TMS-induced seizures with intermittent theta-burst stimulation or with 1 Hz over the right prefrontal cortex.

Figure 1 Patients with an rTMS-induced seizure categorized by area of cortex stimulated (cortex), sex, type of TMS administered, and possible risk factors.

Reports were heterogeneous when reporting potential risk factors for seizures, but most identified at least one potential risk factor that could contribute to increasing the probability of inducing a seizure during rTMS treatment. These risk factors include neurological insult or preexisting condition, including multiple sclerosis, stroke, and traumatic brain injury,Citation28,Citation29,Citation32,Citation36–Citation38,Citation40,Citation42 interrupted sleep pattern,Citation31,Citation35,Citation39 and a history of seizures.Citation33,Citation41 The six remaining case reports did not contain enough information to determine if risk factors were present.Citation23,Citation27,Citation34 With regards to the event reported by Chiramberro et al,Citation24 Wall and colleaguesCitation43 suggested that rTMS may have not been the primary factor in inducing the seizure. Wall et al discussed that the adolescent patient was taking multiple psychotropic medications, where olanzapine was given outside of the acceptable dosing range at 75 mg/d. They further discussed that with the high blood alcohol content, rTMS should not have been delivered that day. Thus, this case exemplifies the importance of having definitive guidelines based on the risk factors for rTMS treatment.Citation43

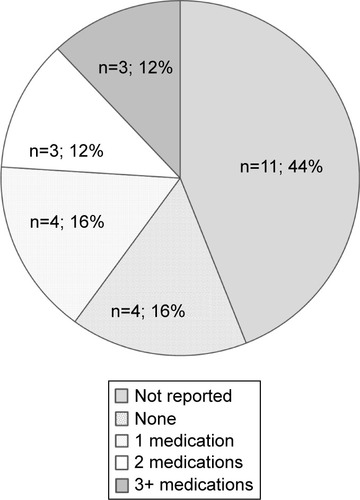

In terms of medications, all patients who had a mood disorder were on at least one medication, the majority being on two or three medications (). The antidepressants are varied, and no particular antidepressant is overrepresented. There are no cases of rTMS-induced seizures where the patient was taking bupropion.

Figure 2 The number and combination of medications that each of the patients (n=25) was taking during the time of accidental rTMS-induced seizure: including no medication (none, n=4, 16%), one medication (n=4, 16%), two medications (n=3, 12%), three medications or more (n=3, 12%), and medications not reported (n=11, 44%).

Only one seizure has been documented by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) involving a patient taking bupropion during rTMS treatment.Citation44 The patient was on the tenth rTMS treatment session of the second course of rTMS therapy when she began to have tonic–clonic movements. The patient was taking other medications other than bupropion that also decreased seizure threshold, namely, sertraline and amphetamine. In addition, the patient was likely sleep deprived as she worked a night shift before treatment. The patient made a full recovery, and the supervising psychiatrist declared that the seizure was due to an “equipment failure” (from report on FDA).Citation44

Discussion

Data available on the rare occurrence of TMS-induced seizures do not show an overrepresentation of any particular antidepressant. However, there are some factors that seem to be more prevalent in rTMS-induced seizures, namely HF-rTMS, motor cortex stimulation, pre-existing conditions, polypharmacy, sleep deprivation, and past history of seizures.

Currently, standard guidelines of rTMS do not exclude the use of bupropion while receiving rTMS treatment, including the suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of rTMSCitation23 or with the FDA. Based on the current evidence, a low dose (<400 mg XR and <300 mg SR) of bupropion taken by patients undergoing rTMS seems to be a safe means of delivering treatment to those with clinical depression. As there is limited research investigating this area, the issue still remains controversial. More studies are needed to look at bupropion and its effect on the seizure threshold to accurately determine if the caution behind bupropion and rTMS is justified.

In addition to well-known risk factors of inducing an accidental rTMS seizure, medication has been suggested to also pose as a possible risk factor.Citation20 As described earlier, bupropion IR was found to be associated with increased rate of seizures in a dose-dependent manner in particular populations, which led some authors to hypothesize that it might decrease seizure threshold in rTMS. In this regard, Mufti and HoltzheimerCitation45 showed in a case study of an individual patient that RMT determined by rTMS was reduced from a mean of 71% device output to 64% mean device output when a patient was concurrently taking 300 mg/d of bupropion compared to taking no bupropion or 150 mg/d of bupropion. Although this anecdotal piece of evidence is interesting, its inferential capacity is very limited (note the authors used an independent-samples t-test for repeated measures of RMT on that single patient, which can misrepresent significance). RMT has also been shown to be quite variable between treatment days as it can be influenced by electrode and coil placement errors as well as other influences on cortical and spinal excitability such as circadian rhythms and circulating hormone levels.Citation46 Therefore, a small fluctuation in RMT within a participant is not a determinant factor when investigating bupropion’s influence on motor threshold.

Based on this study and the past seizure history of bupropion in the late 1980s, some physicians and patients might raise the question as to what is the potential risk when contemplating a course of rTMS while taking bupropion. This might represent a barrier to a significant number of depressed patients as bupropion is a popular antidepressant that lacks the undesirable side effects of other antidepressants. Unbeknownst to many, most antidepressants taken alone have a similar risk of seizure to bupropion ranging from 0.1% to 0.4% (),Citation47–Citation56 with popular antipsychotics ranging from 0.5% to 0.9%. In comparison, the incidence of seizure on the general population without medication is 0.07%–0.09%.Citation57

Table 2 Seizure incidence rates (in percent) for popular antidepressants and antipsychotics based in the literature

Over a thousand treatments have been documented, which have allowed patients to concomitantly receive bupropion and rTMS treatment successfully. Janicak et alCitation58 had 34 out of 36 patients on bupropion who received a total of 1,053 rTMS treatments (average 20 treatments/person) for up to 12 weeks without inducing a seizure. Kleinjung et alCitation59 investigated bupropion as an add-on medication with rTMS for tinnitus treatment as bupropion is a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor that may potentiate low-frequency (LF)-rTMS by enhancing neuroplasticity. Eighteen patients received 150 mg of bupropion XR 4 hours before each rTMS session, for a total of ten sessions, while 100 matched tinnitus patients received rTMS treatment alone. They found that there was no difference between the 100 matched controls to those who received bupropion as an add-on medication and also reported no serious adverse events during the study. In addition, the University Health Network rTMS Clinic at Toronto Western Hospital has administered ~20,000 treatments without accidental seizure and regularly treat patients taking bupropion (up to 300 mg, divided into two doses). Similarly, the Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention has administered >20,000 treatments without inducing a seizure in a bupropion patient, with estimates of 5%–10% of the patients on bupropion. There are no restrictions at the Temerty Centre on bupropion other than the daily dose should not exceed 300 mg.

When considering all rTMS-induced accidental seizures reported in the literature (), none of the patients were taking bupropion with one report from the FDA outlining multiple risk factors. Further, bupropion was not stated as an exclusion criterion for any of the aforementioned research studies. The higher proportion of seizures reported using HF-rTMS compared to LF-rTMS might be related to the fact that HF-rTMS acutely increases cortical excitability, whereas LF-rTMS decreases cortical excitability. Furthermore, LF-rTMS has been explored as a therapeutic tool to treat refractory epilepsy.Citation60 Based on the literature, other popular medications for mood disorders including antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs, atypical), antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and mood stabilizers were present when a seizure was initiated. Thus, it seems that rTMS may be a viable option for patients taking appropriate doses of bupropion, and certainly data do not support a change in the classification on the guidelines by The Safety of TMS Consensus Group to class 1 (strong potential hazard).Citation3 Also, data do not support considering bupropion as an absolute contraindication to receive rTMS in the context of mood disorders. A systematic and comprehensive approach to reporting rTMS side effects, including seizures, would benefit clinicians and patients alike. Specifically, a system akin to the pharmacovigilance programs for medications could be established for medical devices. This medical-device-vigilance program would set standards for reporting adverse events associated with medical devices, thereby increasing the reporting rates and information accuracy.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 PRISMA flow diagram.Citation1

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table S1 rTMS characteristics and information on seizures

Reference

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KennedySHMilevRGiacobbePCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT)Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. IV. Neurostimulation therapiesJ Affect Disord2009117S44S5319656575

- JhanwarVGBishnoiRJJhanwarMRUtility of repetitive transcranial stimulation as an augmenting treatment method in treatment-resistant depressionIndian J Psychol Med2011331929622021964

- RossiSHallettMRossiniPMPascual-LeoneASafety of TMS Consensus Group. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and researchClin Neurophysiol2009120200819833552

- TrippACBupropion, a brief history of seizure riskGen Hosp Psychiatry201032221621720302998

- TrivediMHFavaMWisniewskiSRMedication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depressionN Engl J Med2006354121243125216554526

- LamRWKennedySHGrigoriadisSCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. PharmacotherapyJ Affect Disord2009117S26S4319674794

- DhillonSYangLPCurranMPBupropionDrugs200868565368918370448

- DamajMICarrollFIEatonJBEnantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptorsMol Pharmacol200466367568215322260

- ColemanCCKingBRBolden-WatsonCA placebo-controlled comparison of the effects on sexual functioning of bupropion sustained release and fluoxetineClin Ther20012371040105811519769

- CroftHSettleEJrHouserTBateySRDonahueRMAscherJAA placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and effects on sexual functioning of sustained-release bupropion and sertralineClin Ther199921464365810363731

- PapakostasGINuttDJHallettLATuckerVLKrishenAFavaMResolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsBiol Psychiatry200660121350135516934768

- U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationWellbutrin XL (Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets)Silver Spring, MDU.S. Food and Drug Administration2011

- ZimmermanMPosternakMAAttiullahNWhy isn’t bupropion the most frequently prescribed antidepressant?J Clin Psychiatry200566560361015889947

- DordingCMMischoulonDPetersenTJThe pharmacologic management of SSRI-induced side effects: a survey of psychiatristsAnn Clin Psychiatry200214314314712585563

- HorneRLFergusonJMPopeHGJrTreatment of bulimia with bupropion: a multicenter controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry19884972622663134343

- Vila-RodriguezFDownarJBlumbergerDMRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression: a changing landscapePsychiatric Times201313 Available from: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/depression/repetitive-transcranial-magnetic-stimulation-depression-changing-landscapeAccessed October 12, 2015

- ConcaADi PauliJBerausWCombining high and low frequencies in rTMS antidepressive treatment: preliminary resultsHum Psychopharmacol200217735335612415555

- DaskalakisZJChristensenBKFitzgeraldPBChenRTranscranial magnetic stimulation a new investigational and treatment tool in psychiatryJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200214440641512426408

- GeorgeMSLisanbySHSackeimHATranscranial magnetic stimulation: applications in neuropsychiatryArch Gen Psychiatry199956430031110197824

- LooCKMcFarquharTFMitchellPBA review of the safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as a clinical treatment for depressionInt J Neuropsychopharmacol2008110113114717880752

- MachiiKCohenDRamos-EstebanezCPascual-LeoneASafety of rTMS to non-motor cortical areas in healthy participants and patientsNeurophysiol Clin20061172455471

- MaizeyLAllenCPDervinisMComparative incidence rates of mild adverse effects to transcranial magnetic stimulationNeurophysiol Clin20131243536544

- WassermannEMRisk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the international workshop on the safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, June 5–7, 1996Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol199810811169474057

- ChiramberroMLindbergNIsometsäEKähkönenSAppelbergBRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induced seizures in an adolescent patient with major depression: a case reportBrain Stimulat201365830831

- BagatiDMittalSPraharajSKSarcarMKakraMKumarPRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation safely administered after seizureJ ECT2012281606122343584

- HuSHWangSSZhangMMRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced seizure of a patient with adolescent-onset depression: a case report and literature reviewJ Int Med Res20113952039204422118010

- HarelEVZangenARothYRetiIBrawYLevkovitzYH-coil repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of bipolar depression: an add-on, safety and feasibility studyWorld J Biol Psychiatry201112211912620854181

- GómezLMoralesLTrápagaOSeizure induced by sub-threshold 10-Hz rTMS in a patient with multiple risk factorsNeurophysiol Clin2011122510571058

- RosaMAPicarelliHTeixeiraMJRosaMOMarcolinMAAccidental seizure with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulationJ ECT200622426526617143158

- SakkasPTheleritisCGPsarrosCPapadimitriouGNSoldatosCRJacksonian seizure in a manic patient treated with rTMSWorld J Biol Psychiatry20089215916018428081

- PrikrylRKucerovaHOccurrence of epileptic paroxysm during repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatmentJ Psychopharmacol200519331315888504

- BernabeuMOrientFTormosJMPascual-LeoneASeizure induced by fast repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulationNeurophysiol Clin2004115717141715

- ConcaAKönigPHausmannATranscranial magnetic stimulation induces ‘pseudoabsence seizure’Acta Psychiatr Scand2000101324624910721875

- WassermannECohenLFlitmanSChenRHallettMSeizures in healthy people with repeated “safe” trains of transcranial magnetic stimuliLancet199634790048258268622349

- TharayilBSGangadharBNThirthalliJAnandLSeizure with single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation in a 35-year-old otherwise-healthy patient with bipolar disorderJ ECT200521318818916127313

- FauthCMeyerBProsiegelMZihlJConradBSeizure induction and magnetic brain stimulation after strokeLancet199233987893621346431

- HömbergVNetzJGeneralised seizures induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation of motor cortexLancet1989334867312232572937

- KandlerRSafety of transcranial magnetic stimulationLancet199033586874694701968184

- ObermanLMPascual-LeoneAReport of seizure induced by continuous theta burst stimulationBrain Stimul20092424624720160904

- BrogmusKProvokation eines epileptischen Anfalls durch transkranielle Magnetstimulation-eine FalldarstellungAktuelle Neurol19982504156158

- Pascual-LeoneAValls-SoléJBrasil-NetoJCohenLGHallettMSeizure induction and transcranial magnetic stimulationLancet199233987999971348836

- ChervyakovAPiradovMChernikovaLCapability of navigated repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation in stroke rehabilitation (Randomized blind sham-controlled study)Journal of the Neurological Sciences20133331246247

- WallCCroarkinPBandelLResponse to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induced seizures in an adolescent patient with major depression: a case reportBrain Stimulation20147233733824629832

- U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationMAUDE Adverse Event Reporting: Neuronetics TMS2011 3004824012-2011-00004

- MuftiMAHoltzheimerPEIIIEpsteinCMBupropion decreases resting motor threshold: a case reportBrain stimulation20103317718020633447

- WassermannEMVariation in the response to transcranial magnetic brain stimulation in the general populationClinical Neurophysiology200211371165117112088713

- Pfizer-RoerigZoloft (sertraline hydrochloride)Pfizer Canada Inc2012

- Eli Lilly and CompanyProzac (fluoxetine hydrochloride)Eli Lilly Canada Inc2008

- GenMedPCMirtazapine Product Monograph2012

- PfizerEffexor XR Capsules (Venlafaxine Hydrochloride) Product Monograph2013

- Eli Lilly and CompanyCymbalta (Duloxetine) Product Monograph2012

- EdwardsJGInmanWHWiltonLPrescription-event monitoring of 10,401 patients treated with fluvoxamineBr J Psychiatry199416433873957993416

- Lundbeck Canada IncCelexa (Citalopram hydrobromide) Product Monograph2012

- GlaxoSmithKline IncPaxil (Paroxetine) Product Monograph2012

- AlperKSchwartzKAKoltsRLKhanASeizure incidence in Psychopharmacological Clinical Trials: an analysis of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) summary basis of approval reportsBiological Psychiatry20076234535417223086

- PreskornSFastGTricyclic antidepressant-induced seizures and plasma drug concentration1002;535160162

- HauserWAKurlandLTThe epidemiology of epilepsy in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935 through 1967Epilepsia1975161166804401

- JanicakPGO’ReardonJPSampsonSMTranscranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a comprehensive summary of safety experience from acute exposure, extended exposure, and during reintroduction treatmentJ Clin Psychiatry200869222223218232722

- KleinjungTSteffensTLandgrebeMRepetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for tinnitus treatment: no enhancement by the dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor bupropionBrain stimulation201142657021511205

- CantelloRRossiSVarrasiCSlow repetitive TMS for drug-resistant epilepsy: clinical and EEG findings of a placebo-controlled trialEpilepsia200748236637417295632