Abstract

The purpose of the present paper is to review and summarize the research supporting nonpharmacologic treatment options for insomnia. The different treatment approaches are described followed by a review of both original research articles and meta-analyses. Meta-analytic reviews suggest that common nonpharmacologic approaches exert, on average, medium to large effect sizes on SOL, WASO, NWAK, SQR, and SE while smaller effects are seen for TST. Stimulus control therapy, relaxation training, and CBT-I are considered standard treatments for insomnia by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). Sleep restriction, multicomponent therapy without cognitive therapy, paradoxical intention, and biofeedback approaches have received some levels of support by the AASM. Sleep hygiene, imagery training, and cognitive therapy did not receive recommendation levels as single (standalone) therapies by the AASM due to lack of empirical evidence. Less common approaches have been introduced (Internet-based interventions, bright light treatment, biofeedback, mindfulness, acupuncture, and intensive sleep retraining) but require further research. Brief and group treatments have been shown to be as efficacious as longer and individually-administered treatments. Considerations are presented for special populations, including older adults, children and teens, individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, insomnia comorbid with other disorders, and individuals who are taking hypnotics.

Introduction

Insomnia, defined as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep with impaired daytime functioning, is a prevalent complaint among the general population. Studies indicate that approximately 30% of the population report sleep disruption, while 10% report sleep disruption accompanied by daytime fatigue.Citation1 Insomnia can be classified in several ways. For example it can be primary (not due to another sleep disorder or underlying psychiatric, medical, or substance abuse condition) or comorbid (occurring with another condition). It can also be classified as acute (ie, less than four weeks) or chronic (eg, greater than four weeks).

In addition to being a prevalent condition, the consequences of insomnia are significant and include increased risk of health problems, health-care utilization, work absenteeism, reduced productivity, and nonmotor-vehicle accidents.Citation2 Based on a six-month period in 2003, Ozminkowski and colleagues estimated that the economic costs for those diagnosed with insomnia are greater than $1000 more than those not diagnosed with insomnia.Citation3

According to the National Institutes of Health, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-I) and pharmacotherapy (benzodiazepine receptor agonists)Citation4 are the two types of treatments that currently meet the criteria for use in the clinical management of insomnia. The purpose of the present paper is to review and summarize the research supporting nonpharmacologic treatment options for insomnia. The different treatment options will first be defined, followed by a review of common approaches and emerging/less common approaches, and treatment considerations for special populations. This paper will conclude with an evaluation of the overall effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions.

Assessment of insomnia

Researchers and clinicians have used a variety of objective and subjective techniques to assess sleep. Objective and subjective measures play different roles in both the research and clinical assessment of insomnia. Objective measurement through the use of polysomnography is useful within both clinical and research settings for ruling out occult sleep disorders such as sleep apnea. In particular, polysomnography can be useful for identifying sleep disordered breathing in older adults because self-reports of snoring and breathing cessation may not be as reliable in this population.Citation5 Conversely, subjective measures, such as sleep diaries, are more important for the assessment of insomnia symptoms. Sleep diaries are a daily self-report measurement of sleep that requires individuals to document specific information regarding their previous night’s sleep (eg, bedtime, number of minutes spent awake). Given the subjective nature of the insomnia complaint, a self-report measure is necessary to assess appropriately an individual’s subjective sleep experience.

Research has been conducted to develop sufficient quantitative criteria to use self-report measures to diagnose insomnia in an effective manner. According to Lichstein and colleagues, the DSM-IV, ICSD, and ICD-10 do not offer sufficient quantitative criteria for diagnosing insomnia.Citation6 They claim that this lack of a standardized set of quantitative criteria for evaluating self-reported sleep onset latency (SOL) and wake after sleep onset (WASO) is particularly problematic for research purposes because it produces undesirable variability in insomnia research. To address this issue, Lichstein and colleagues reviewed 61 clinical insomnia trials conducted during the 1980s and 1990s and used sensitivity-specificity analyses to identify the most empirically defensible quantitative criteria for insomnia.Citation6 Based on their analyses, they recommend the following minimum insomnia diagnostic criteria for SOL or WASO of: (a) at least 31 minutes; (b) occurring at least three nights per week; (c) having occurred for at least six months.

While poor sleep is essential to diagnosing insomnia, daytime impairment is also needed for a diagnosis of insomnia.Citation7 Lichstein and colleagues examined insomniacs’ responses on five questionnaires that assess various aspects of daytime functioning.Citation6 Based on their examination, they established cut-offs for each questionnaire. Specifically, according to Lichstein and colleagues, a person who surpasses the cutoff score on at least one of the following five questionnaires meets the daytime impairment criteria necessary for a diagnosis of insomnia.

It is important to note that the cutoffs recommended below are specific to assessing level of daytime impairment relative to insomnia. Each instrument has other established cutoffs for diagnosing the symptoms/disorder they were originally designed to assess. For example, the cutoff score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS); (see below for more details) that indicates an individual has a level of daytime sleepiness consistent with a diagnosis of apnea (≥ 11) is different from the recommended cutoff (≥7.4) for assessing insomnia-related daytime impairment. This distinction is particularly important, because true daytime sleepiness (the tendency to fall asleep in sedentary situations) is a hallmark symptom of apnea and can be useful in differentiating between insomnia and apnea. Specifically, apneics report higher tendencies for daytime sleepiness and are more likely to fall asleep; whereas insomniacs will frequently report daytime sleepiness, but further assessment typically indicates that their likelihood of actually falling asleep is relatively low (consistent with hyperarousal-related theories of insomnia). Polysomnographic assessment may be indicated for individuals who report a high level of likelihood of falling asleep during the day (eg, a score of ≥11). While questionnaires can be useful in assessing daytime impairment, they are not always necessary because a thorough clinical sleep history interview can also be used to assess daytime impairment.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The ESS measures trait daytime sleepiness in everyday situations.Citation8 Participants indicate how likely they are to fall asleep in eight common, quiet daytime activities over the previous two weeks. The possible range of scores is from 0 to 24, with increasing scores indicating increasing daytime sleepiness. The recommended cutoff for the ESS is ≥7.4.Citation9

Insomnia Impact Scale

The Insomnia Impact Scale (IIS) is the most wide-ranging index of daytime functioning in insomnia available.Citation10 The questionnaire contains 40 negative statements about the daytime impact of sleep. Respondents rate each item on a five-point scale to register their degree of agreement. The range of possible scores is from 40 to 200, with increasing scores indicating increasing impact of insomnia on daytime functioning. The recommended cutoff for the IIS is ≥ 125.Citation9

Fatigue Severity Scale

The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) comprises nine items that assess the intrusion of fatigue.Citation11 Responses are averaged across the nine items, yielding a possible score range of 1–7. The cutoff for the FSS is ≥5.5.Citation9

Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a widely used 21-item survey that measures negative affect, cognitions, and behavior.Citation12 The recommended cutoff for the BDI is ≥ 10.Citation9

State-trait Anxiety Inventory Trait Scale (STAI)

The State-trait Anxiety Inventory Trait Scale (STAI) is one of the most commonly used anxiety inventories. The STAI consists of 20 self-descriptive statements.Citation13 A cutoff score of ≥ 37 is recommended.Citation9

Methods

A review of the literature was conducted to identify studies focused on nonpharmacologic treatments for insomnia. Articles published from 1972 to 2009 were included in the review. Search terms included: insomnia and treatment; stimulus control; paradoxical techniques; paradoxical intention; sleep restriction; sleep compression; sleep hygiene; and sleep education. The following search terms combined with insomnia were also used: nonpharmacologic therapy, behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, alternative medicine, relaxation, group therapy, telephone therapy, internet therapy, bright light therapy, and biofeedback. Where possible, meta-analyses are included in the review because they are considered the “gold-standard” of clinical evidence. Literature searches were conducted using the ISI Web of Science, PsychInfo, and PubMed databases, and Google Scholar.

Throughout this review, a number of sleep outcomes are described. The majority of outcomes are derived from sleep diary data because self-report data is the recommended standard for assessment of insomnia complaints. The sleep variables assessed by the studies include time taken to fall asleep (sleep onset latency; SOL), the number of times an individual awakens (number of awakenings, NWAK), time spent awake during the night after initial sleep onset (WASO), total time spent asleep (total sleep time; TST), efficiency of sleep defined as a ratio of time spent sleeping to time spent in the bed (sleep efficiency; SE), and the quality of sleep (sleep quality rating; SQR).

Treatment components of psychological and behavioral interventions

The purpose of this section is to outline and discuss the mechanics of common cognitive and behavioral treatments for insomnia. These interventions include stimulus control, sleep restriction, sleep compression, relaxation training, and cognitive therapy (summarized in ).

Table 1 Summary of psychological and behavioral treatments for insomnia

Stimulus control

Bootzin originated the concept of stimulus control for sleep in 1972,Citation14 and it has since enjoyed considerable success and confirmation as an effective monotherapy for insomnia. Stimulus control is based on the notion that with any behavior, one stimulus may elicit many responses depending on the history of conditioning. Stimuli of the bed and bedroom elicit associations of relaxation and sleep in healthy sleepers. While stimulus control dictates that the bed and bedroom should be used solely for sleep and sex, people with insomnia often have a history of engaging in many sleep-disruptive behaviors in the bedroom, including reading, eating, worrying, watching television, and engaging in arousing conversation. They often perceive that spending excessive time in or near the bed increases their chances of getting more sleep, when this actually weakens the stimulus-response relationship between being in bed and falling sleep. Over time, the stimuli of the bed and bedroom can become cues for anxiety and frustration associated with trying to fall asleep. Additionally, internal cues such as mind-racing and physiological arousal can become interoceptive cues for further arousal and sleep disruption.Citation15 Stimulus control instructions often include using the bedroom only for sleep (or sex), getting out of bed if awake for 15 to 20 minutes (and returning only when sleepy), avoiding napping, and setting regular bed and wake times. Importantly, stimulus control is contraindicated in patients with mania, epilepsy, and parasomnias, or those who are at risk for falls.Citation16

Sleep restriction

Sleep restriction therapy consists of limiting the amount of time spent in bed to the actual amount of time spent sleeping, such that these two values nearly mirror each other after treatment.Citation17 Sleep diary data is used to establish the average amount of time-in-bed using data from the previous one or two weeks. A sleep efficiency percentage is computed by dividing the average time spent sleeping by the average time-in-bed and multiplying this number by 100. Sleep efficiency is then used to determine the prescribed time-in-bed. During followup sessions, the time-in-bed prescription is often titrated up or down based on sleep diary data from the previous week. Sleep restriction allows a slight sleep debt to accrue whereby on subsequent nights, patients often fall asleep more easily and experience more consolidated sleep. Sleep restriction therapy is contraindicated for patients with a history of mania, obstructive sleep apnea, seizure disorder, parasomnias, or those at risk for falls.Citation16

Sleep compression

A variation on sleep restriction therapy is called sleep compression therapy. While sleep restriction therapy abruptly reduces the time the patient is allowed to spend in bed, sleep compression therapy decreases the time gradually (eg, time-in-bed is reduced gradually over a five-week period rather than during one weekCitation18).

Relaxation

Relaxation training is useful in reducing the physical and mental tension reported by many patients with insomnia. These methods are especially useful with insomnia patients who evidence a great deal of hypervigilance or physical complaints that can interfere with adaptive sleep patterns. The most common types of relaxation for treating insomnia include progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training, imagery, and meditation.Citation16,Citation19 A passive form of progressive muscle relaxation may be used that eliminates the tensing phase of this particular method. With all relaxation methods, the clinician instructs the patient to adapt a calm, passive attitude and to use relaxation on a consistent basis in order to elicit the parasympathetic response before going to bed and/or during awakenings after sleep onset. The clinician encourages the patient to be an active consumer in discovering the relaxation method(s) that are optimally effective, based on their own self-knowledge. Lastly, the importance of practice in eliciting the relaxation response is emphasized. Relaxation training often plays an important role in multicomponent approaches to the treatment of insomnia and has been shown to be effective in meta-analytic reviews (see discussion below).

Paradoxical intention

Paradoxical intention involves instructing the patient to attempt to stay awake while remaining in bed at night. The rationale behind this approach is that by attempting to stay awake, the stress and frustration associated with trying to fall asleep will be reduced.

Imagery training

To engage in imagery training, the patient selects a relaxing image or memory and invokes the image using multiple senses in order to create a sense of relaxation.

Cognitive therapy

MorinCitation20 and HarveyCitation21 have provided models of cognitive therapy for insomnia.Citation21,Citation22 Cognitive therapy involves uncovering faulty underlying beliefs regarding sleep, providing alternative interpretations, and allowing the patient to consider their insomnia in a different way.Citation23 Morin and colleaguesCitation23,Citation24 have described five primary aims for cognitive therapy (see ). These aims address cognitive distortions specific to insomnia that can be addressed through discussion with the therapist and by completion of thought records outside of sessions.

Table 2 Primary aims of cognitive therapyCitation23,Citation24

The clinician can also encourage time for constructive worryCitation25 as a means of coping with “unfinished business” from the day. Here, the patient writes down their concerns and possible solutions to their concerns. This can be a means of providing some sense of calm and closure to life stressors before initiating sleep. The use of distraction with imagery has also been successful in managing unwanted pre-sleep thoughts.Citation26

Multicomponent therapy

When used to treat insomnia, CBT-I is an umbrella term for treatment packages that include three or more insomnia techniques. Although the exact components included in CBT-I vary, techniques that are commonly included are sleep hygiene, stimulus control, sleep restriction, cognitive therapy, and relaxation training (see above for a discussion of the individual components). Sleep hygiene is not discussed separately because it is rarely studied as a “stand-alone” treatment. As there is not sufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of sleep hygiene as a sole approach, we will discuss it within the context of a multicomponent approach. CBT-I is traditionally conducted following a thorough sleep history interview. Treatment occurs face-to-face over four to eight weekly sessions that are 60 to 90 minutes in length. Treatment can be conducted in individual or group format. Frequently, the clinician begins by providing the patient with sleep hygiene and sleep education information on the basic mechanics of sleep and sleep-disrupting practices. In terms of sleep education, the clinician provides information on the prevalence of insomnia and intrapersonal variability in the amount of sleep needed. Common insomnia-perpetuating factors such as increasing sleep opportunity by spending excessive time in bed and napping are explained. The clinician then highlights the notion that, fortunately, sleep-promoting skills can be relearned with effort and practice. While debate exists concerning the instructions that sleep hygiene includes, bedroom factors and the use of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, exercise, and heavy meals late in the day are commonly included.Citation27 Sleep hygiene and sleep education information are not recommended as stand-alone treatments for insomnia, because research does not support their efficacy when used as monotherapies. However, CBT-I protocols including sleep hygiene and sleep education have been shown to be efficacious.

Regardless of the specific technique or techniques used to treat a person with insomnia, treatment typically begins by instructing the patient how to complete a sleep diary and by informing them that they will complete the sleep diary each day throughout the treatment period. Morin describes the order of events in the typical treatment session as reviewing the sleep diary and progress from the previous week, identifying problems encountered in home practice, negotiating strategies for better treatment adherence, introducing the new treatment component, presenting supportive didactic material, and reviewing homework assignments.Citation22

Review of studies using common psychological and behavioral interventions

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of common psychological and behavioral interventions (sleep hygiene, relaxation, stimulus control, sleep restriction/compression, cognitive therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy) will be reviewed first. Several meta-analytic studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions for insomnia. Meta-analytic studies compile results from multiple studies which enables the calculation of the effect sizes of different treatments. Throughout this review, effects sizes are primarily reported using Cohen’s d, a measure of effect size thought of as how many standard deviations separate the means of two groups. Effect sizes are classified as minor (0.20), medium (0.50), and large (0.80).Citation28 The treatment outcomes for the meta-analyses were derived primarily from sleep diary data. Five meta-analytic studies were conducted between 1994 and 2006. The three most recent of the meta-analyses specifically focus on the treatment of older adults. Additionally, a comprehensive review of the literature was published by Morin and colleagues.Citation29 Recent studies are also presented.

Overall effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions

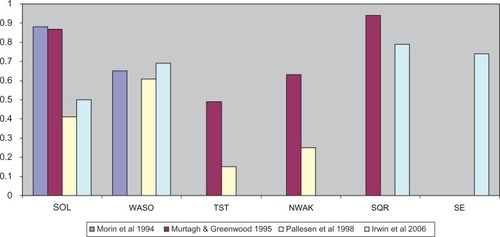

Meta-analyses of the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions have been conducted between 1994Citation30 and 2006Citation29 (see ). The studies have covered the time period of 1973 to 2004. A variety of psychological interventions were included in the analyses, such as stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation therapy, paradoxical intention, biofeedback, sleep hygiene education, combined behavioral approaches, imagery training, cognitive-behavioral treatment, and multicomponent approaches. Statistically significant changes in sleep were found for SOL (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.4131–0.8830), WASO (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.6131–0.6932), TST (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.1531–0.4933), NWAK (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.2531–0.6333), SE (d = 0.7432) and SQR (effect sizes ranging from d = 0.7932–0.9433; see ). In addition to studies reporting effect sizes, Montgomery and Dennis saw modest treatment effects for WASO (decrease of 22 minutes) and TST (increase of 14.6 minutes) and minimal gains for SOL (decrease of three minutes).Citation34 Differential effects of the treatment approaches were found in some of the reviews, with the most effective treatments overall being stimulus controlCitation30,Citation33 and combination treatments,Citation32,Citation33 with lower effectiveness reported for paradoxical intention.Citation33 In terms of the duration of treatment effects, clinical gains were maintained on average for sixCitation30,Citation31 to eightCitation33 months.

Figure 1 Average size of treatment effects (Cohen’s d) on sleep variables from meta-analyses reporting effect sizes.

Table 3 Summary of meta-analytic studies evaluating psychological and behavioral treatments

A study by Morin and colleagues reviewed the evidence for psychological and behavioral interventions for insomnia from studies within the time period of 1998 to 2004.Citation29 Using the criteria developed by the American Psychological Association,Citation35 the authors identified the following five treatments as meeting the criteria for well-established treatments for insomnia: stimulus control therapy, relaxation training, paradoxical intention, sleep restriction, and CBT-I. The authors noted that there was a trend/preference for investigators to combine two or more interventions when treating insomnia. In particular, they noted that the most common approaches involved an educational (sleep hygiene), behavioral (stimulus control, sleep restriction, relaxation), and cognitive therapy component.Citation29

Recent studies

Research conducted since the most recent meta-analyses supports the above conclusions. Morin and colleagues found that CBT-I therapy with adults aged 30 to 72 with persistent insomnia showed significant improvements in sleep diary SOL (−19.9 minutes), WASO (−68.7 minutes), and SE (+14.4%).Citation36 Additionally, participants showed significant improvements in polysomnography measured SOL (−6.4 minutes), WASO (−27.2 minutes), and SE (+5.5%). Similarly, a recent study by Edinger and colleagues showed that CBT-I therapy significantly improved sleep outcomes (SOL [−19.8 minutes], WASO [−36 minutes], and SE [+12.1%]) for those diagnosed with primary insomnia, with a mean age of 54.2 years.Citation37

Relative effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions

While the above studies provide substantial evidence supporting the efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions in general for insomnia, the relative efficacy of interventions remains unclear. While some studies have compared single therapy or combinations of treatments, there remains a lack of consensus as to the “best” single or combined therapies. In 2006, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) released a report describing the evidential support for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia.Citation38 The AASM classified treatments according to the level of evidence with scores ranging from the highest level of evidence (level I for a randomized trial with low alpha and beta error) to the lowest (level V for a case series). Additionally, the AASM provided a level of recommendation for each treatment. Interventions could be classified as a “standard” recommendation (generally accepted strategy with level I or II evidence), “guideline” (moderate degree of clinical certainty with level II or III evidence), or “option” (uncertain clinical use with inconclusive or conflicting evidence). Based on these criteria, stimulus control therapy, relaxation training, and CBT-I were recommended as standard treatments for insomnia. Sleep restriction, multicomponent therapy without cognitive therapy, paradoxical intention, and biofeedback received the guideline level of recommendation. Finally, sleep hygiene, imagery training, and cognitive therapy did not receive a recommendation level as a single therapy because there was insufficient evidence.

Interestingly, the AASM also stated that there was insufficient evidence to recommend one single therapy over another or to recommend a single therapy versus a combination of psychological and behavioral interventions. The relative efficacy of the single components of CBT-I has yet to be evaluated within a single study.

Review of emerging/less common treatment approaches

In addition to common psychological and behavioral treatments for insomnia, researchers and clinicians have also attempted to utilize new and nontraditional treatment approaches. While there is a dearth of empirical evidence supporting some of the newer treatments, they represent an innovative approach to the treatment of insomnia and consequently are reviewed here. These approaches include brief and group approaches as well as internet-based interventions, bright light treatments, techniques based on mindfulness meditation, and acupuncture. Additionally, biofeedback is reviewed. While it is not a new treatment, it represents a less commonly used approach.

Brief and group approaches

Traditionally, CBT-I protocols for insomnia last between six to 10 sessions and involve one-to-one meetings between the patient and clinician. These protocols require a large commitment on both the part of the clinician as well as patients. Because of these demands, researchers have sought to develop intervention protocols that require fewer sessions or personnel demands.

According to McCrae and colleagues,Citation39 research has shown that both brief and group approaches for the treatment of insomnia can be as efficacious as traditional CBT-I approaches. Furthermore, brief and group treatments of insomnia have been utilized with a broad array of patient populations.Citation39

Brief approaches

According to Morin and colleagues,Citation29 the average number of treatment sessions given for insomnia is 5.7 meetings.Citation29 Based on their work, brief interventions are defined herein as treatment approaches that last for five or fewer sessions.

Numerous researchers have utilized four-session brief interventions. For example, McCrae and colleaguesCitation40 used a brief behavioral treatment with an older rural adult sample. The results showed improvements in SOL and SE. The treatment included stimulus control, sleep restriction, and passive relaxation.Citation40 Lichstein and colleaguesCitation41 also used a four-session protocol to determine the efficacy of a brief approach for alleviating sleep complaints in a sample of older adults with secondary insomnia. Their treatment protocol consisted of sleep hygiene, stimulus control, and relaxation exercises. The results showed that the treatment led to significant improvements in WASO, SOL, SE, and SQR.Citation41

Other researchers have examined the impact of even briefer interventions. Edinger and SampsonCitation42 conducted a two-session cognitive-behavioral intervention. They found that participants showed a significant decrease in WASO, improved SE, and higher SQR.Citation42 Another example is a study conducted by Chambers and Alexander that utilized a one-session approach. Their results indicated that SOL significantly decreased, WASO significantly decreased, and TST significantly increased.Citation43 In contrast, other researchers have implemented group treatments for insomnia.

Group approaches

According to McCrae and colleagues,Citation39 research has shown that group approaches have been successfully used with a wide array of populations. Researchers have conducted groups with as few as two peopleCitation44 to as many as fifteen.Citation45 The length of the treatment protocol ranges from three weekly sessionsCitation46 to eleven weekly sessions.Citation47 Additionally these approaches have been utilized with adolescentsCitation44 and adults up to the age of 85 years.Citation45

While group approaches vary in treatment approaches, most have contained at least one component of traditional cognitive-behavioral approaches. These approaches have been shown to improve sleep significantly.Citation39 One of the additional benefits of a group approach is that the interactions among group members can strengthen the therapeutic benefit of group treatment.Citation48

Briefer treatment protocols and the group administration of CBT-I provide useful alternatives to traditional treatments, because they reduce the time required of the clinician and are more appealing to patients. Additionally, studies of brief and group treatment of insomnia have demonstrated the utility of these approaches across a variety of ages and patient populations. Lastly, the effect sizes for both brief and group approaches are similar to the sizes of effect of traditional cognitive behavioral treatments of insomnia.Citation39 These findings indicate that both brief and group treatment approaches are appropriate and as efficacious as traditional protocols. In addition to these brief and group treatment approaches, other treatment approaches have also been utilized.

Other approaches

Internet-based interventions, bright light treatments, biofeedback, and techniques based on mindfulness meditation and acupuncture have also been utilized to treat insomnia. For example, Ritterband and colleagues conducted a nine-week Internet intervention that included stimulus control, sleep hygiene, sleep restriction, relapse prevention, and cognitive restructuring. They found that the treatment led to significant improvements in WASO (decreased by 55%) and SE (increased by 16%).Citation49 Vincent and Lewycky conducted a six-week Internet intervention that found significant improvements in SQR (+0.35) and significant declines in insomnia severity and daytime fatigue.Citation50 Conversely, an Internet-based treatment intervention found that while the treatment group showed improvement on the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale,Citation51 few significant differences between the treatment and control groups were seen in improvements in sleep.

Lack and colleagues utilized a different technique to treat insomnia. They conducted a study that examined the impact of two bright light treatments on sleep. They found that the participants in the bright light treatment experienced a reduction in WASO and an increased TST.Citation52

Ong and colleagues utilized another technique to treat insomnia. They integrated mindfulness meditation with CBT-I. The treatment lasted for six weeks and a significant correlation was found between the number of meditation sessions and arousal measures. The authors concluded that integrating mindfulness meditation led to significant improvement in insomnia symptoms, including total wake time (−55 mins), SE (+9.08%), and NWAK (−0.99).Citation53 Additionally, Ong and colleagues conducted a study with the same sample one year later and found that the treatment benefits were maintained.Citation54

Acupuncture is another technique that has been used for the treatment of insomnia.Citation55 The authors found that both acupuncture and acupressure may help improve sleep quality when compared with control groups. Furthermore, Yeung and colleagues found that electro-acupuncture was helpful for increasing sleep efficiency.Citation56 While these findings are encouraging, more evidence is needed to support the use of these techniques.Citation55

Recently, researchers have begun to study another treatment approach known as intensive sleep retraining. This treatment approach is a condensed behavioral conditioning treatment occurring over a one-night period. The patient is allowed to sleep for brief periods of time (up to four minutes) before being awakened. The goal of the treatment is to decondition the insomnia arousal response to sleep onset, resulting in decreased sleep onset latency. Preliminary results suggest that intensive sleep retraining shows promise for decreasing SOL and increasing TST.Citation57

While not a new approach, biofeedback is a treatment that has been used regularly in the past, but is less commonly used now. This technique provides feedback to patients to help them develop control over physiological responses that leads to a decrease in arousal. In the AASM report by Morgenthaler and colleagues it was concluded that this technique could be used with a moderate degree of clinical certainty.Citation38 Additionally, Bootzin and Ryder’s review of the literature on biofeedback revealed that biofeedback can be effective in the treatment of insomnia.Citation58 They specifically examined electromyography (EMG), theta electroencephalography (EEG), and sensorimotor rhythm EEG. They found that EMG biofeedback can produce decreases in SOL, decreases in NWAK, decreases in WASO, and increased TST. However, they concluded that this technique was no more effective than relaxation training. According to Bootzin and Ryder’s review, a few studies have shown that EEG biofeedback can be effective in the treatment of insomnia. However, few studies have utilized this technique in the last 30 years. Lastly, sensorimotor rhythm biofeedback has been shown to lead to an increase in the number and duration of sleep spindles, decreases in SOL, and an increase in the percentage of time spent in REM sleep.Citation58

Considerations for special populations

The majority of empirical studies evaluating the effectiveness of psychological and behavioral interventions for insomnia have focused on healthy, community-dwelling adults with primary insomnia. Special consideration is required when implementing nonpharmacologic interventions with other populations, such as with older adults, children and teens, and individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. Additionally, consideration must be taken when treating comorbid insomnia and when treating individuals who are taking hypnotics.

Older adults

Epidemiological research in the US suggests that the prevalence of insomnia increases across the lifespan among both men and women and is at its highest level late in life.Citation59 Among older adults, those in their 70s are most likely to have maintenance insomnia (ie, difficulty maintaining sleep).Citation59 In addition, older women are more likely than older men to have insomnia.Citation59 Additionally, there is likely to be a high proportion of older individuals whose insomnia is comorbid in nature.Citation60–Citation63

Reviews and meta-analyses have supported the overall efficacy of psychological treatments for insomnia among older adults.Citation31,Citation64–Citation68 Differences in the approaches to treating insomnia in older adults include differing expectations of sleep outcomes (eg, for sleep efficiency). For example, a goal of greater than 85% sleep efficiency is strived for rather than the 90% criteria used with younger adults.Citation69 Also, difficulties may arise when trying to generalize results from research studies to the general older adult population because the majority of these studies were conducted in healthy, medication-free, community-dwelling and well-educated older adults. In reality, the presentation of insomnia among older adults is more likely to be comorbid with other disorders and these people are more likely to be using medications.Citation69 In fact, the use of hypnotic medication by older adults is reported to be nearly five times the rate of younger adults.Citation70,Citation71 Consequently, clinicians using psychological treatments with older adults should be prepared for patients with a history of sleeping medication use and possible dependence or tolerance to sleeping medication. Given the multifaceted presentation of sleeping difficulties in older adults (eg, comorbid with other medical conditions and hypnotic use) multicomponent approaches should be considered to target most effectively the treatment needs of this population. For a complete discussion of the psychological treatment of insomnia in older adults see McCrae, Dzierzewski, and Kay,Citation72 or Dzierzewski and colleagues’ article concerning sleeplessness in older adults in the current volume.

Children and teens

Among children and teens, the definition and etiology of insomnia is much the same as among adults. However, the context surrounding the presenting complaint will be altered as the patient is often not the source of complaint. For children, sleeping difficulties are more likely to be voiced by the parent than the child. When assessing sleep difficulties in children, developmental stages must be taken into account to determine whether a sleep problem is normative.Citation73 Additionally, the daytime impact of sleep disturbance among children may present differently than with adults, and is more likely to be characterized by behavior disturbance, irritability, and neuropsychological deficits.Citation74,Citation75

Cognitive-behavioral treatment for sleep disturbance among children is based on many of the same principles as adults (ie, learned associations, physiological arousal). However, treatment of childhood insomnia requires the parent or guardian to implement much of the treatment, rather than the patient themselves. Parents play an essential role in developing and maintaining good sleep behaviors for their children, and especially among those with sleep disorders.Citation76 While the techniques described in the current article apply more generally to adults, many of them may be useful for preteens/teens depending on the level of cognitive/emotional development of the individual and their degree of control over their own sleep/wake schedule. However, the techniques are not all equally generalizable to children. For example, stimulus control and sleep restriction, resulting in an initial decrease in sleep time, is likely to lead to mood and behavior problems rather than an increased sleep debt that will be helpful or therapeutic. Techniques specifically identified for treating childhood sleep disturbances include extinction and parent training (a preventative measure).Citation77–Citation79 An extinction treatment would advise the parent to ignore a child’s bedtime tantrum for a specific period of time followed by a brief check-in by the parent.Citation76 See the Mindell reviewCitation76 for further evaluation of empirically supported treatments for childhood sleep disturbances.

Cultural differences

While there are known differences in the rates and presentation of sleep difficulties by different cultural groups, there has been a severe lack of research on cultural/ethnic differences in response to psychological treatments for insomnia. In terms of the presentation of sleep difficulties, older adult African-Americans are reported to have lower rates of insomnia than Caucasians.Citation80–Citation82 Caucasian and European American participants have reported fewer complaints of daytime napping than minority groups in the US, while Caucasian individuals tend to report higher rates of sleep medication use than African-American individuals.Citation83–Citation85 To date, there are no treatment studies that directly compare the treatment response of African-Americans and Caucasians. A comprehensive review of sleep literature pertaining to African-Americans has been done by Lichstein et al.Citation9 Epidemiological studies from around the world have estimated the prevalence and incidence of chronic insomnia to be from 5% to 20% in local populations (Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Sweden, and the US).Citation86–Citation91

Comparing samples from Japan and Western countries indicates that the prevalence, risk factors, and role of cognitive processes in the maintenance of insomnia are almost identical between these cultures.Citation88,Citation90,Citation92–Citation94 Differences have been reported in some of the perpetuating behaviors of insomnia, where Japanese participants were found to be more likely to spend time engaging in nocturnal activities.Citation92,Citation95

Comorbid insomnia

Most research has studied insomnia in isolation, known as primary insomnia. Insomnia symptoms related to another physical, psychological, or drug-induced condition were considered secondary to the primary diagnosis and referred to as “secondary insomnia”. Recently, however, the National Institutes of Heath State of the Science Conference on Manifestation and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults (2005) recommended that insomnia classification should focus on comorbid insomnia diagnosis, rather than secondary insomnia. The classification of insomnia as comorbid rather than as secondary to other disorders is important, given how insomnia develops. According to the behavioral model of insomnia proposed by Spielman and colleagues, insomnia can develop in response to both predisposing and precipitating factors, and be maintained due to perpetuating factors.Citation96 Predisposing characteristics such as hyperarousal can place an individual at increased risk for developing insomnia. Precipitating factors, such as disrupted sleep due to another illness, can instigate an acute insomnia episode. Finally, perpetuating factors include changes in behavior such as lying awake in bed while ill which can lead to maladaptive behaviors that prolong the insomnia.Citation96 Consequently, while an individual may develop insomnia concomitant with or due to another disorder, insomnia can be perpetuated due to maladaptive behaviors and continue to require treatment in the absence of the comorbid illness.Citation97

In recent years, interest has increased in evaluating the efficacy of psychological treatments for comorbid insomnia. A complete review of this literature is beyond the scope of this article but a brief synopsis is provided. Case studies have shown that cognitive and behavioral treatments improved insomnia among people with cancer,Citation98 chronic pain,Citation99,Citation100 depression and pain,Citation101 hemophilia,Citation102 psychiatric disorders,Citation103 and multiple medical problems.Citation104 Randomized empirical studies have explored the effects of cognitive and behavioral therapies for insomnia and found them to be efficacious among those with chronic pain,Citation105–Citation107 fibromyalgia,Citation107 cancer,Citation108–Citation110 early stage Alzheimer’s disease,Citation111 alcohol dependence,Citation112 and older adults with medical diagnoses and psychiatric diagnoses.Citation37 A review of the diagnosis and treatment of comorbid/secondary insomnia has been done by McCrae and Lichtein.Citation113 In addition to this research, McCrae and colleagues are currently conducting several NIH-funded studies examining the efficacy of CBT-I in patients experiencing chronic pain, patients with cardiac disease who have implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and patients with gynecologic cancers undergoing chemotherapy. The study examining cognitive-behavioural therapy in patients with chronic pain uses cognitive-behavioral interventions specific to insomnia (CBT-I) and chronic pain (CBT-P) to examine the causal links between sleep and pain. Additionally, the study is collecting neuroimaging data pre- and post-CBT-I to examine the neural mechanisms by which CBT-I interventions could interrupt the development and maintenance of increased sensitivity to pain. The study examining sleep in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators is collecting data on the prevalence of sleep disorders in these patients. Currently, information regarding the specific types of sleep disorders experienced by this population is not available. In addition to examining the prevalence of sleep disorders, this study is testing the effectiveness of a brief CBT-I intervention specifically designed to improve sleep in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. This research will also assess the cognitive functioning of these patients across the sleep disorders, including insomnia, apnea, etc. A third ongoing study is examining the effectiveness of CBT-I among women with gynecologic cancers undergoing chemotherapy. The study is using a multicomponent intervention with the goals of improving sleep and pain, and reducing cortisol levels in these women.

Insomnia and use of hypnotics

While older adults report the highest rates of hypnotic use, younger adults also report high levels of hypnotics used to treat sleep problems.Citation72,Citation114 Not surprisingly, individuals diagnosed with insomnia report higher rates of hypnotic use than those with undiagnosed sleep problems. As medication is often the first line of treatment, it is highly likely that individuals presenting for nonpharmacologic treatment of insomnia will have a history of pharmacologic treatment for insomnia. Data suggest that the combination of carefully administered CBT-I and pharmacologic treatment should result in a beneficial interaction.Citation115 However, there are insufficient data at this time to make any conclusions.Citation116 Research has shown that the use of CBT-I techniques (stimulus control, sleep hygiene, and relaxation) among hypnotic-dependent younger and older adults with insomnia can lead to statistically and clinically significant improvements in sleep and to reduced medication usage when compared with placebo.Citation117,Citation118

Whether to withdraw a patient from hypnotics over the course of psychological treatment or to maintain the patient’s medications is often unclear because of concerns about the withdrawal process possibly resulting in worsened insomnia, often referred to as “rebound insomnia”. A number of studies suggest that CBT-I is an efficacious technique to facilitate withdrawal from benzodiazepines and third-generation hypnotics among hypnotic-dependent younger and older adults.Citation70,Citation119–Citation121 Patients are likely to experience a brief worsening of their insomnia symptoms but this is likely to subside within a few weeks. It is helpful to prepare patients for the side effects of withdrawal prior to beginning the withdrawal process, to monitor for symptoms of withdrawal throughout treatment, and to withdraw hypnotics gradually to ease the transition.

Conclusion

Various psychological and behavioral interventions have been studied as treatments for insomnia. Meta-analyses suggest that common nonpharmacologic approaches exert, on average, a medium to large effect size on sleep variables such as SOL, WASO, NWAK, SQR, and SE (see ). Less significant effects are seen for TST which is understandable given that sleep treatments such as sleep restriction may curtail the total amount of time spent sleeping.Citation122 Additionally, the AASM has concluded that stimulus control therapy, relaxation training, and CBT-I can be considered standard treatments for insomnia. Sleep restriction, multicomponent therapy without cognitive therapy, paradoxical intention, and biofeedback have received some levels of support. Finally, sleep hygiene, imagery training, and cognitive therapy did not receive a recommendation level as a single therapy as there was insufficient evidence.

In addition to the more common approaches to treating insomnia, research has evaluated emerging or less common approaches. Brief and group treatments have been shown to be as efficacious as longer and individually-administered treatments. Additionally, evidence is promising for emerging/less common treatments such as Internet-based interventions, bright light treatment, biofeedback, mindfulness, acupuncture, and intensive sleep retraining. Additional research, with randomized controlled trials, is required to support the efficacy of these approaches for treating insomnia. Finally, special consideration is required when implementing nonpharmacologic interventions with certain populations such as with older adults, children and teens, insomnia comorbid with another disorder, and insomnia with hypnotic use.

Future directions include examining the longevity of treatment effects, examining treatment effects with diverse samples, and recruiting “ecologically valid” samples consisting of individuals who experience comorbid disorders and other health complaints.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- OhayonMMEpidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learnSleep Med Rev2002629711112531146

- DaleyMMorinCMLeBlancMGregoireJPSavardJBaillargeonLInsomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidentsSleep Med200910442743818753000

- OzminkowskiRJWangSHWalshJKThe direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia in adults in the United StatesSleep200730326327317425222

- National Institutes of HealthState of the Science Conference Statement – Manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adultsSleep20052891049105716268373

- YoungTShaharENietoFJPredictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults – The sleep heart health studyArch Intern Med2002162889390011966340

- LichsteinKLDurrenceHHTaylorDJBushAJRiedelBWQuantitative criteria for insomniaBehav Res and Ther200341442744512643966

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed.Washington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- JohnsMWA new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scaleSleep19911451811320

- LichsteinKLDurrenceHHRiedelBWTaylorDJBushAJEpidemiology of Sleep: Age, gender, and ethnicityHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc2004

- HoelscherTJWareJCBondTInitial validation of the Insomnia Impact ScaleSleep Res199322149

- KruppLBLaRoccaNGMuir-NashJSteinbergADThe Fatigue Severity Scale: Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosusArch of Neurol19894610112132803071

- BeckATSteerRABeck Depression InventoryOrlando, FLPsychological Corporation1987

- SpielbergerCDGorsuchRLLusheneRVaggPRJacobsGAStait-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Form YPalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1983

- BootzinRRA stimulus control treatment for insomniaProceedings of the 80th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association1972395396

- BootzinRREpsteinDRStimulus controlLichsteinKLMorinCMTreatment of Late-life InsomniaThousand Oaks, CASage Publications2000

- PerlisMLJungquistCSmithMTPosnerDCognitive Behavioral Treatment of InsomniaNew York, NYSpringer2005

- SpielmanAJSaskinPThorpyMJTreatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bedSleep198710145563563247

- LichsteinKLNauSDMcCraeCSStoneKCPsychological and behavioral treatments for secondary insomniasKrygerMHRothTDementWCPrinciples and Practice of Sleep MedicinePhiladelphia, PASaunders2005

- LichsteinKLRelaxationLichsteinKLMorinCMTreatment of Late-life InsomniaThousand Oaks, CASage Publications2000

- MorinCMInsomnia. Psychological assessment and managementNew York, NYGuilford Press1993

- HarveyAGA cognitive model of insomniaBehav Res and Ther200240886989312186352

- MorinCMA cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of insomniaInsomnia: Psychological assessment and management New York, NYGuilford Press1993

- MorinCMEspieCAInsomnia: A clinical guide to assessment and treatmentNew York, NYKluwer Academic/Plenum2003

- BelangerLSavardJMorinCMClinical management of insomnia using cognitive therapyBehav Sleep Med20064317920216879081

- CarneyCEWatersWFEffects of a structured problem-solving procedure on pre-sleep cognitive arousal in college students with insomniaBehav Sleep Med200641132816390282

- HarveyAGPayneSThe management of unwanted pre-sleep thoughts in insomnia: Distraction with imagery versus general distractionBehav Res Ther200240326727711863237

- MorinCMEspieCAInsomnia: A clinical guide to assessment and treatmentNew York, NYSpringer2004

- CohenJStatistical power analysis for the behavioral sciencesNew YorkAcademic Press1977

- MorinCMBootzinRRBuysseDJEdingerJDEspieCALichsteinKLPsychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998–2004)Sleep200629111398141417162986

- MorinCMCulbertJPSchwartzSMNonpharmacological interventions for insomnia – A meta-analysis of treatment efficacyAm J Psychiatry19941518117211808037252

- PallesenSNordhusIHKvaleGNonpharmacological interventions for insomnia in older adults: A meta-analysis of treatment efficacyPsychotherapy1998354472482

- IrwinMRColeJCNicassioPMComparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middleaged adults and in older adults 55+ years of ageHealth Psychol200625131416448292

- MurtaghDRRGreenwoodKMIdentifying effective psychological treatments for insomnia – a meta-analysisJ of Consult and Clin Psychol199563179897896994

- MontgomeryPDennisJA systematic review of non-pharmacological therapies for sleep problems in later lifeSleep Med Rev200481476215062210

- ChamblessDLHollonSDDefining empirically supported therapiesJ Consult and Clin Psychol1998667189489259

- MorinCMVallieresAGuayBCognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: A randomized controlled trialJAMA2009301192005201519454639

- EdingerJDOlsenMKStechuchakKMcognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominantly with mixed psychiatric disorders: A randomized clinical trialSleep200932449951019413144

- MorgenthalerTKramerMAlessiCPractice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: An update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine ReportSleep Nov2006291114151419

- McCraeCSDautovichNDDzierzewskiJMShort-term and group approachesSateiaMJBuysseDJInsomnia: Diagnosis and treatmentNew YorkInforma Healthcare USA, Inc.2010

- McCraeCSMcGovernRLukefahrRStriplingAMResearch evaluating brief Behavioral sleep treatments for rural elderly (RESTORE): A preliminary examination of effectivenessAm J Geriatr Psychiatry2007151197998217974868

- LichsteinKLWilsonNMJohnsonCTPsychological treatment of secondary insomniaPsychol Aging200015223224010879578

- EdingerJDSampsonWSA primary care “friendly” cognitive behavioral insomnia therapySleep200326217718212683477

- ChambersMJAlexanderSDAssessment and prediction of outcome for a brief behavioral insomnia treatment programJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry1992 Dec234289971302254

- BootzinRRStevensSJAdolescents, substance abuse, and the treatment of insomnia and daytime sleepinessClin Psychol Rev200525562964415953666

- ConstantinoMManberROngJJuoTHuangJArnowBPatient expectations and therapeutic alliance as predictors of outcome in group cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomniaBehav Sleep Med20075321022817680732

- BorkovecTDSteinmarSWNauSDRelaxation training and single-item desensitization in group treatment of insomniaJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry197344401403

- SchrammEHohagenFBackhausJLisSBergerMEffectiveness of a multicomponent group treatment for insomniaBehav Cogn Psychother1995232109127

- VerbeekIKoningsGAldenkampADeclerckAKlipECognitive behavioral treatment in clinically referred chronic insomniacs: Group versus individual treatmentBehav Sleep Med20064313515116879078

- RitterbandLMThorndikeFPGonder-FrederickLAEfficacy of an internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomniaArch Gen Psychiatry200966769269819581560

- VincentNLewyckySLogging on for better sleep: RCT of the effectiveness of online treatment for insomniaSleep200932680781519544758

- MorinCStoneJTrinkleDMercerJRemsbergSDysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep among older adults with and without insomniaPsychol Aging199384634678216967

- LackLWrightHKempKGibbonSThe treatment of early-morning awakening insomnia with 2 evenings of bright lightSleep200528561662316171276

- OngJCShapiroSLManberRCombining mindfulness meditation with cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: A treatment-development studyBehav Ther200839217118218502250

- OngJCShapiroSLManberRMindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A naturalistic 12-month follow-upEXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing2009513036

- CheukDKLYeungWFChungKFWongVAcupuncture for insomniaCochrane Database Syst Rev2007183CD00547217636800

- YeungWFChungKFZhangSPYapTGLawACKElectroacupuncture for primary insomnia: A randomized controlled trialSleep20093281039104719725255

- HarrisJLackLWrightHGradisarMBrooksAIntensive sleep retraining treatment for chronic primary insomnia: A preliminary investigationJ Sleep Res20071627628417716277

- BootzinRRRiderSPBehavioral techniques and biofeedback for insomniaPressmanMROrrWCUnderstanding Sleep: The evaluation and treatment of sleep disordersWashington, DCAmerican Psychological Association1997

- LichsteinKLDurrenceHRiedelBWTaylorDJBushAEpidemiology of sleep: Age, gender, and ethnicityMahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates2004

- FoleyDAncoli-IsraelSBritzPWalshJSleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America surveyJ Psychosom Res200456549750215172205

- NewmanABEnrightRLManolioTAHaponikEEWahlPWSleep disturbance, psychosocial correlates, and cardiovascular disease in 5201 older adults: The cardiovascular health studyJ Am Geriatr Soc1997451147214789400557

- OhayonMMCarskadonMAGuilleminaultCVitielloMVMeta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespanSleep20042771255127315586779

- VitielloMVMoeKEPrinzPNSleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adults: Clinical research informed by and informing epidemiological studies of sleepJ Psychosom Res200253155555912127171

- IrwinMRColeJCNicassioPMComparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and in older adults 55+ years of ageHealth Psychol200625131416448292

- MorinCMMimeaultVGagneANonpharmacological treatment of late-life insomniaJ Psychosom Res199946210311610098820

- MorinCMHauriPJEspieCASpielmanAJBuysseDJBootzinRRNonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine reviewSleep19992281134115610617176

- MurtaghDRGreenwoodKMIdentifying effective psychological treatments for insomnia: A meta-analysisJ Consult Clin Psychol199563179897896994

- NauSDMcCraeCSCookKGLichsteinKLTreatment of insomnia in older adultsClin Psychol Rev200525564567215961205

- LichsteinKLMorinCMTreatment of Late-Life InsomniaThousand Oaks, CASage Publications2000

- LichsteinKLJohnsonRSRelaxation for insomnia and hypnotic medication use in older womenPsychol Aging1993811031118461107

- Quera-SalvaMAOrlucAGoldenbergFGuilleminaultCInsomnia and use of hypnotics: Study of a French populationSleep19911453863911759090

- McCraeCSDzierzewskiJKayDTreatment of late-life insomniaSleep Med Clin2009459360423390408

- OwensJAPediatric insomniaSleep Med Clin2006112

- RandazzoACMuehlbachMJSchweitzerPKWalshJKCognitive function following acute sleep restriction in children ages 10–14Sleep19982188618689871948

- SmedjeHBromanJEHettaJAssociations between disturbed sleep and behavioural difficulties in 635 children aged six to eight years: A study based on parents’ perceptionsEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry20011011911315530

- MindellJAEmpirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Bedtime refusal and night wakings in young childrenJ Pediatr Psychol199924646548110608096

- WolfsonALacksPFuttermanAEffects of parent training on infant sleeping patterns, parents’ stress, and perceived parental competenceJ Consult Clin Psychol199260141481556284

- AdairRZuckermanBBauchnerHPhilippBLevensonSReducing night waking in infancy: A primary care interventionPediatrics1992894 Pt 15855881557234

- KerrSMJowettSASmithLNPreventing sleep problems in infants: A randomized controlled trialJ Adv Nurs19962459389428933253

- BlazerDGHaysJCFoleyDJSleep complaints in older adults: A racial comparisonJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci1995505M2802847671031

- FoleyDJMonjanAABrownLSSimonsickEMWallaceRBBlazerDGSleep complaints among elderly persons: An epidemiologic study of three communitiesSleep19951864254327481413

- Jean-LouisGMagaiCMCohenCIZiziEvon GizyckiHDiPalmaJEthnic differences in self-reported sleep problems in older adultsSleep200124892693311766163

- Jean-LouisGMagaiCCasimirGJInsomnia symptoms in a multiethnic sample of American womenJ Womens Health (Larchmt)2008171152518240978

- QureshiAIGilesWHCroftJBBliwiseDLHabitual sleep patterns and risk for stroke and coronary heart disease: A 10-year follow-up from NHANES INeurology19974849049119109875

- Ancoli-IsraelSKlauberMRStepnowskyCEstlineEChinnAFellRSleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderlyAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951526 Pt 1194619498520760

- ChevalierHLosFBoichutDEvaluation of severe insomnia in the general population: Results of a European multinational surveyJ Psychopharmacol1999134 Suppl 1S212410667452

- OhayonMMHongSCPrevalence of insomnia and associated factors in South KoreaJ Psychosom Res200253159360012127177

- TachibanaHIzumiTHondaSTakemotoTIThe prevalence and pattern of insomnia in Japanese industrial workers: Relationship between psychosocial stress and type of insomniaPsychiatry Clin Neurosci19985243974029766687

- MorphyHDunnKMLewisMBoardmanHFCroftPREpidemiology of insomnia: A longitudinal study in a UK populationSleep200730327428017425223

- KimKUchiyamaMOkawaMLiuXOgiharaRAn epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general populationSleep200023141710678464

- ZailinawatiAAriffKNurjahanMTengCEpidemiology of insomnia in Malaysian adults: a community-based survey in 4 urban areasAsia Pac J Public Health200820322423319124316

- HarveyAGregoryABirdCThe role of cognitive processes in sleep disturbance: A comparison of Japanese and English university studentsBehav Cogn Psychother200230259270

- KageyamaTKabutoMNittaHA population study on risk factors for insomnia among adult Japanese women: A possible effect of road traffic volumeSleep199720119639719456461

- MotohashiYTakanoTSleep habits and psychosomatic health complaints of bank workers in a megacity in JapanJ Biosoc Sci19952744674727593053

- LiuXUchiyamaMKimKSleep loss and daytime sleepiness in the general adult population of JapanPsychiatry Res200093111110699223

- SpielmanAJCarusoLGlovinskyPA behavioral perspective on insomnia treatmentPsychiatr Clin North Am198710412

- HauriPChernikDHawkinsDMendelsJSleep of depressed patients in remissionArch Gen Psychiatry19743133863914370375

- StamHJBultzBDThe treatment of severe insomnia in a cancer patientJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry198617133373700668

- FrenchAPTupinJPTherapeutic application of a simple relaxation methodAm J Psychother19742822822874829708

- MorinCMKowatchRAWadeJBBehavioral management of sleep disturbances secondary to chronic painJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry19892042953022534597

- MorinCMKowatchRAO’ShanickGSleep restriction for the inpatient treatment of insomniaSleep19901321831862330476

- VarniJBehavioral treatment of disease-related chronic insomnia in a hemophiliacJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry198011143145

- TanTLKalesJDKalesAMartinEDMannLDSoldatosCRInpatient multidimensional management of treatment-resistant insomniaPsychosomatics19872852662723423177

- KolkoDJBehavioral treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in an elderly woman with multiple medical problemsJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry19841543413456526945

- VitielloMVRybarczykBVon KorffMStepanskiEJCognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia improves sleep and decreases pain in older adults with co-morbid insomnia and osteoarthritisJ Clin Sleep Med20095435536219968014

- CurrieSRWilsonKGPontefractAJdeLaplanteLCognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic painJ Consult Clin Psychol200068340741610883557

- EdingerJDWohlgemuthWKKrystalADRiceJRBehavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients: A randomized clinical trialArch Intern Med2005165212527253516314551

- CanniciJMalcolmRPeekLATreatment of insomnia in cancer patients using muscle relaxation trainingJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry19831432512566358270

- FiorentinoLCognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Breast Cancer Survivors: A randomized controlled crossover studyAnn Albor, MIDissertation Abstracts International2008

- SavardJSimardSIversHMorinCMRandomized study on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part II: Immunologic effectsJ Clin Oncol200523256097610616135476

- McCurrySMGibbonsLELogsdonRGVitielloMVTeriLNighttime insomnia treatment and education for Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc200553579380215877554

- ArnedtJTConroyDRuttJAloiaMSBrowerKJArmitageRAn open trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia comorbid with alcohol dependenceSleep Med20078217618017239658

- McCraeCSLichsteinKLSecondary insomnia: Diagnostic challenges and intervention opportunitiesSleep Med Rev200151476112531044

- StewartRBessetABebbingtonPInsomnia comorbidity and impact and hypnotic use by age group in a national survey population aged 16 to 74 yearsSleep200629111391139717162985

- ZavesickaLBrunovskyMHoracekJTrazodone improves the results of cognitive behaviour therapy of primary insomnia in non-depressed patientsNeuro Endocrinol Lett200829689590119112384

- MendelsonWBCombining pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies for insomniaJ Clin Psychiatry200768Suppl 5192317539705

- MorganKDixonSMathersNThompsonJTomenyMPsychological treatment for insomnia in the management of long-term hypnotic drug use: A pragmatic randomised controlled trialBr J Gen Pract20035349792392814960215

- SoeffingJPLichsteinKLNauSDPsychological treatment of insomnia in hypnotic-dependent older adultsSleep Med20089216517117644419

- LichsteinKLPetersonBARiedelBWMeansMKEppersonMTAguillardRNRelaxation to assist sleep medication withdrawalBehav Modif199923337940210467890

- MorinCMBastienCGuayBRadouco-ThomasMLeblancJVallieresARandomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomniaAm J Psychiatry2004161233234214754783

- ZavesickaLBrunovskyMMatousekMSosPDiscontinuation of hypnotics during cognitive behavioural therapy for insomniaBMC Psychiatry200888018801160

- RiemannDPerlisMLThe treatments of chronic insomnia: A review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapiesSleep Med Rev200913320521419201632