Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrine disorder affecting the reproductive, metabolic and psychological health of women. Clinic-based studies indicate that sleep disturbances and disorders including obstructive sleep apnea and excessive daytime sleepiness occur more frequently among women with PCOS compared to comparison groups without the syndrome. Evidence from the few available population-based studies is supportive. Women with PCOS tend to be overweight/obese, but this only partly accounts for their sleep problems as associations are generally upheld after adjustment for body mass index; sleep problems also occur in women with PCOS of normal weight. There are several, possibly bidirectional, pathways through which PCOS is associated with sleep disturbances. The pathophysiology of PCOS involves hyperandrogenemia, a form of insulin resistance unique to affected women, and possible changes in cortisol and melatonin secretion, arguably reflecting altered hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function. Psychological and behavioral pathways are also likely to play a role, as anxiety and depression, smoking, alcohol use and lack of physical activity are also common among women with PCOS, partly in response to the distressing symptoms they experience. The specific impact of sleep disturbances on the health of women with PCOS is not yet clear; however, both PCOS and sleep disturbances are associated with deterioration in cardiometabolic health in the longer term and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Both immediate quality of life and longer-term health of women with PCOS are likely to benefit from diagnosis and management of sleep disorders as part of interdisciplinary health care.

Introduction

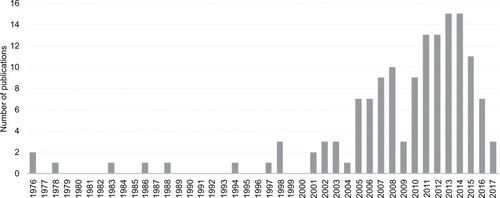

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrine disorder with implications for reproductive, psychological and metabolic health. Despite first being identified in the 1930s, recognition of an association between PCOS and sleep disturbances is relatively recent. A search of the PubMed database indicates that the majority of research on this topic has been published after 2005 and the body of work remains quite small ().

Figure 1 The number of articles published in PubMed per year on the topic of PCOS and sleep.

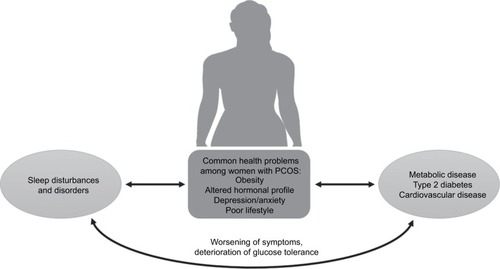

In this review, we first provide an overview of PCOS and summarize the clinical and epidemiological literature pertaining to sleep disturbances and disorders among women with the condition. The pathways through which PCOS may influence sleep are then described in detail, focusing on the endocrine, psychosocial and behavioral characteristics that are often present among women with PCOS, drawing attention to probable bidirectional relationships (). Current knowledge about the long-term consequences of PCOS for cardiometabolic health is outlined as well as the potential contribution of impaired sleep to deterioration of health profiles.

Figure 2 Summary of the bidirectional pathways through which PCOS interacts with sleep disturbances, with potentially detrimental effects on long-term cardiometabolic health.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

PCOS is an endocrine disorder that manifests in an array of symptoms that varies from one woman to another.Citation1 This heterogeneity has hampered the definition of the syndrome, etiological research, recognition in clinical practice and appropriate treatment and support for women.

PCOS was first recognized as a clinical entity in the 1930s. At that time it was named Stein–Leventhal syndrome, after the two clinicians who first reported the disorder in seven women who presented with hirsutism, amenorrhea and enlarged bilateral polycystic ovaries, along with obesity.Citation2,Citation3 Once considered a reproductive disorder acquired by adult women, it is now widely accepted that PCOS is a lifelong metabolic condition.Citation4

Features of the syndrome classically emerge during puberty, but diagnosis can be difficult because irregular menstruation is common in normal development.Citation1,Citation5 Excess body hair accumulates gradually, reflecting increasing duration of androgen exposure. Some girls (and women) with PCOS have severe acne vulgaris (predominantly on the lower face, neck, chest and upper back).Citation1

Historically, recognition of PCOS by clinicians was erratic.Citation6,Citation7 In addition, reluctance to seek medical advice (e.g. due to embarrassment) meant that many women did not receive a diagnosis until they sought fertility treatment, or lifelong.Citation8 Undiagnosed PCOS is still relatively common.Citation9

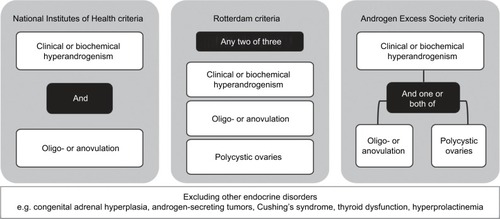

Currently, there are three sets of criteria for diagnosing PCOS, summarized in . Differences between the criteria reflect controversy about the pathogenesis of PCOS and the different forums in which experts’ opinions were canvassed.Citation3 In 1990, experts at a conference sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) produced the first attempt at defining PCOS clinically. The NIH criteria specify (in order of importance) that clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism should be present as well as oligo- or anovulation (i.e. irregular or no periods).Citation10 In 2003, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine produced a statement, known as the Rotterdam criteria, specifying that two out of the following three must be met for a diagnosis of PCOS: clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, oligo- or anovulation and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.Citation11 In 2006, the Androgen Excess Society (AES) Taskforce produced criteria specifying that hyperandrogenism must be present for diagnosis, in addition to either oligo- or anovulation or polycystic ovaries on ultrasound (or both).Citation12 There have been several attempts to subclassify the syndrome using clinical and metabolic criteria, without universal agreement.Citation3,Citation13

Figure 3 A summary of the three sets of criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS: the National Institutes of Health criteria (1990),Citation10 the Rotterdam criteria (2003)Citation11 and the Androgen Excess Society criteria (2006).Citation12

All diagnostic criteria specify that diagnosis of PCOS should only be made after exclusion of other endocrine disorders including congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-secreting tumors, Cushing’s syndrome, thyroid dysfunction and hyperprolactinemia. Early studies of women with PCOS suggested they had elevated prolactin, and explored overlap in symptoms between hyperprolactinemia and PCOS, but these are now considered to be two distinct conditions.Citation14–Citation18

Beyond the enlargement of ovaries originally noted by Stein and Leventhal,Citation2 ovaries with multiple cysts (follicles with arrested development) have other features, including a thickened covering capsule and greatly increased stromal tissue. The thecal and stromal layers produce excess androgen, and this led to the view that pathogenesis is primarily ovarian.Citation19 While recognizing wider metabolic involvement, the AES takes the position that PCOS is primarily a disorder of hyperandrogenism.Citation12 Lack of consensus on this matter persists because hormone signaling has a major role in systems such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, so the disorder could have a central origin, and there are conflicting results from interventions in which androgens were reduced in women with PCOS.Citation3 Additionally, constructive debate is impeded by lack of a reliable assay designed to measure androgens in the range relevant to women, approximately one-tenth that of men.Citation20,Citation21

Research undertaken in the 1980s demonstrated insulin resistance in women with PCOS, underpinning the alternative view that this is the cardinal feature of the syndrome, with hyperinsulinemia causing hyperandrogenemia and anovulation.Citation3 Even lean women with PCOS generally have insulin resistance of an intrinsic form,Citation22 which appears to be the result of a defect in post-binding insulin signaling that disturbs metabolic but not mitogenic functions.Citation23 This abnormality appears unique to PCOS, as it has not been observed in other conditions of insulin resistance, including obesity and type 2 diabetes.Citation24 Thus, when women with PCOS have high body weight, they are affected by both intrinsic and extrinsic insulin resistance.Citation3 PCOS has recently been conceptualized as a condition of severe metabolic stress,Citation25 a position that we support as it provides a way to account for the pervasive molecular and biochemical derangements that occur in PCOS and variation in symptom profiles.

Clustering of diagnosed PCOS and isolated hormonal and metabolic symptoms within families supports a genetic component to the etiology of PCOS;Citation26 however, phenotypic variation suggests that multiple genes are involved.Citation27 Familial and cohort studies have identified numerous gene loci as candidates for conferring susceptibility to PCOS. These include polymorphisms in loci associated with androgen receptors and with insulin signaling. For many of the candidate loci, it remains unclear as to how they relate to specific PCOS characteristics.Citation27

Support for fetal or early life origins of PCOS stems from animal models in which exposure to androgen excess, or growth restriction or acceleration, has produced symptoms of PCOS.Citation3,Citation28 It is unlikely that maternal androgens reach the fetus in human pregnancies, although fetal ovarian androgen production is possible.Citation3 Birth phenotypes in humans have consistently been associated with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome.Citation29–Citation32

While we accept a genetic contribution, our researchCitation33,Citation34 is premised on interactions with the fetal environment producing epigenetic changes that culminate in PCOS.Citation35 Hypothesized “programming” of metabolic function is not simply about growth of the fetus or size at birth, although these are overt signs of perturbed development in utero.Citation36 A range of conditions, including maternal under- and overnutrition and mental distress, can inhibit the activity of an enzyme in the placenta (11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase) that is critical to reducing fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids.Citation37 Through this process, it is proposed that overexposure of the fetus alters the set points and function of the HPA axis, with profound implications for metabolism.

Uncertainties about PCOS also persist because it is difficult to study in representative population-based samples of women. Obtaining self-reports of doctor-diagnosed PCOS will result in misclassification of a substantial proportion of women as unaffected. Some symptoms can be reported reliably but others require invasive tests, and the sensitive nature of symptoms may affect participation. Thus, few studies with community-based samples have been undertaken to date, although clinic-based samples have been reported on extensively.

We retrospectively established a birth cohort of Australian women using records from a large maternity hospital.Citation9 We traced over 90% of 2199 female babies three decades after they were born. Around half of the young women who were eligible joined the study and completed an initial interview in which medical and reproductive history, including symptoms of PCOS, were reported. Women were asked to provide a blood sample for assessment of free testosterone. Those with evidence of both hyperandrogenism and oligo- or anovulation were classified as having PCOS as per the NIH criteria. Women with one or both of those two symptoms were referred to a clinic for ovarian ultrasound so that we could apply the Rotterdam criteria. The prevalence of PCOS was 8.7 ± 2.0% with NIH criteria, 11.9 ± 2.4% with Rotterdam criteria assuming those who did not consent to ultrasound did not have cystic ovaries and 17.8 ± 2.8% with Rotterdam criteria using multiple imputation for missing ultrasound data. Over two-thirds of those classified as having PCOS had not been diagnosed previously.

Sleep disturbances and disorders and PCOS

Sleep disturbances include altered sleep duration, delay of sleep onset, difficulty in maintaining sleep or awakening early.Citation38 Insomnia is defined as impairment in the ability to initiate or maintain sleep, including extended periods of wakefulness during the night. Chronic insomnia disorder is diagnosed when insomnia occurs at least three nights per week and for at least three months.Citation39 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by frequent cessations of breathing during sleep and may occur along with other sleep disturbances.Citation40 Clinically, OSA is diagnosed by detecting the frequency of events that are apneic (no airflow for 10 seconds) and hypopneic (decreased airflow for 10 seconds associated with either an oxyhemoglobin desaturation or an arousal detected by electroencephalography), as per the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI). A diagnosis of OSA is made when AHI is ≥15 or when AHI is ≥5 with symptoms such as daytime sleepiness, loud snoring and witnessed breathing interruptions.Citation41

Sleep disturbances and disorders have repercussions for daytime mood, cognition and psychomotor functioning,Citation42 which acutely affect well-being and daily activities, and can inhibit performance in roles such as that of parent or employee.Citation43,Citation44 Aspects of cognition that appear most affected are attention, executive function and working memory,Citation42,Citation45 with significant implications for productivity.Citation44 Fatigue, attention deficits and psychomotor impairment can affect safety, increasing the risk of workplace and motor vehicle accidents.Citation42 Thus, poor sleep represents a serious health problem.

As mentioned, it is difficult to study PCOS in representative population-based samples; so evidence concerning the prevalence of sleep disturbances and disorders across the full spectrum of PCOS severity is limited. We identified only three such studies (), summarized here, each supporting an excess of sleep disturbances and disorders in women with PCOS that was not accounted for by obesity.

Table 1 Summary of population- and community-based studies of sleep disturbances and PCOS in women

Two studies have drawn on the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database in which PCOS and sleep disorders were recorded using International Classification of Diseases codes (and thus required recognition and formal diagnosis).Citation46 In a longitudinal design, data for women with PCOS (n = 4595) and a comparison group of women matched for age (n = 4595) were assembled over 2–8 years. Women with PCOS had greater incidence of OSA (1.71 vs 0.63 per 1000 person-years), a difference not due to obesity or demographic characteristics (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 2.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6–4.0). In the second study, sleep disorders excluding OSA were considered as part of an investigation of PCOS and psychiatric disorders.Citation47 Over a 10-year period, compared to an age-matched comparison group of women (n = 21,724), those with PCOS (n = 5431) were 50% more likely to be diagnosed with a sleep disorder (HR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–1.9).

In the community-based cohort of Australian women that we undertook, sleep disturbances were self-reported using a modified version of the Jenkins questionnaire,Citation48 by 87 women with PCOS (as per Rotterdam criteria) and 637 women of similar age.Citation48 Sleep disturbances, specifically difficulty falling asleep (odds ratio [OR] = 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–3.0) and difficulty maintaining sleep (OR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.3), were twice as common in women with PCOS compared to those without. The former association persisted after accounting for body mass index (BMI) and depressive symptoms, but not the latter. PCOS was not observed to be associated with unintended early morning waking or daytime sleepiness.Citation48

Clinic-based studies of sleep disturbances in women with PCOS

Polysomnographic assessments of clinical samples of women with PCOS have been undertaken, with OSA the focus in the majority (summarized in ). Interpretation of the findings of these studies should be tempered with understanding of the limitations of this literature: clinic-based samples of women with PCOS are likely to comprise women with the most severe symptoms;Citation49 comparison groups are often convenience samples of women attending clinics for reasons other than PCOS; and sample sizes are often modest.

Table 2 Summary of clinic-based studies of sleep disturbances and PCOS in women

OSA is common in clinical samples of women with PCOS, affecting 17–75%, substantially higher than in other women of similar age and BMI, and thus is not attributable to the tendency of women with PCOS to be obese.Citation50–Citation54 One study has shown that OSA is elevated in women who have BMI in the normal range along with PCOS.Citation54 Women with PCOS have consistently been shown to have elevated AHI, regardless of OSA diagnosis.Citation50,Citation51,Citation53–Citation55 Few differences in other polysomnographic variables, such as sleep latency, sleep efficiency and waking after sleep onset, have been found.Citation50,Citation51,Citation54,Citation55

We have not systematically attended to studies of adolescents, given the difficulty in diagnosing PCOS at that stage of development and the likelihood that selection procedures (including factors involved in seeking an early diagnosis) contribute to inconsistent findings in polysomnographic studies.Citation56–Citation58 Of interest, however, one study demonstrated higher AHI and more OSA among obese girls with PCOS (n = 28) referred to a sleep clinic compared with a control group of girls (n = 28) matched for age and BMI, but no differences from a control group of boys (n = 28).Citation59

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is a hallmark of sleep disturbance in men, but may not be as relevant to womenCitation60 who are more likely to report low mood or irritability or morning headaches following poor sleep.Citation48,Citation61 Nevertheless, EDS in women with PCOS has been investigated,Citation50,Citation51,Citation54,Citation55 usually using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.Citation50,Citation51,Citation55 Predominantly, the clinical studies have shown PCOS to be associated with EDS, often in the absence of OSA. For example, in one study 80% of women with PCOS (n = 53) complained of EDS but only 17% were diagnosed with OSA.Citation54

Insomnia in women with PCOS has received very little attention. Among a clinical sample of Polish women with PCOS (n = 95), 13% had insomnia according to the Athens Insomnia Scale and 10% according to the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), with corresponding proportions among controls (n = 130) of 3% and 1%, respectively.Citation62

How pathophysiology of PCOS is linked to sleep disturbances

Since PCOS is characterized by metabolic disturbances, and as the endocrine system has an important role in governing the sleep–wake cycle, it is likely that PCOS interferes with arousal and sleep or that there is a more complex interrelationship.

The sleep–wake cycle in humans is driven by the interaction between two processes, Process S, which is sleep promoting, and Process C, which promotes wakefulness.Citation63 Process S represents the homeostatic need for sleep and accumulates over the time spent awake. Process C is regulated by the circadian system and ensures that sleep and wakefulness coincide with environmental light–dark stimuli.Citation64 The circadian system is coordinated centrally by the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus and is synchronized with environmental stimuli.Citation65 The suprachiasmatic nucleus relays circadian information to other areas of the brain, such as the pituitary and pineal pineal glands, and to peripheral tissues via the regulation of clock-gene expression and neuroendocrine signaling.Citation66

Melatonin and cortisol play important roles in regulating sleep and wakefulness. Melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland, is increased at night and decreased during the day, thus communicating light–dark information.Citation64,Citation67 Cortisol, which is secreted from the adrenal cortex and regulated by the HPA axis, also follows a circadian pattern, steadily increasing during sleep and peaking in the morning.Citation67,Citation68

As illustrated in , there are several pathways through which PCOS and sleep disturbances may be associated. The pathways outlined here have been identified based on the endocrine profiles of women with PCOS, the unique stressors they experience, and related psychological and behavioral factors.

Obesity

Obesity is common in women with PCOS and exacerbates the metabolic stress that we and others view as central to pathogenesis of the syndrome.Citation25 In a meta-analysis of mainly clinic-based samples (n = 35 studies),Citation69 49% of women with PCOS were classified as obese (95% CI 42–55%) and 54% had central adiposity (95% CI 43–62%). The proportions were around twofold higher than among comparison groups (obesity: relative risk [RR] = 2.8, 95% CI 1.9–4.1; central adiposity: RR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.3–2.3). These proportions should not be interpreted as prevalence estimates for all women with PCOS because obesity has been shown to be more common (and more extreme) in clinical samples than in community-based studies.Citation49 For example, in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (overall n = 9145), at wave 4, 478 women reported having received a diagnosis of PCOS and, on average, had moderately higher BMI (mean difference 2.5 kg/m2, 95% CI 1.9–3.1) and moderately greater longitudinal weight gain over a 10-year period (mean difference 2.6 kg kg/m2, 95% CI 1.2–4.0) compared to their peers.Citation70

Variation in BMI among women with PCOS appears to be related to factors such as age and ethnicity and possibly to severity of the syndrome.Citation69 It is not clear why women with PCOS are predisposed to obesity, nor whether it reflects physiology or psychology. Some literature suggests that appetite and satiety are altered in PCOS, with affected women reporting higher postprandial hunger and lower satiety after a test meal compared to other women.Citation71 Underlying postprandial suppression of gut hormones such as ghrelin, cholecystokinin, glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY may occur in PCOS.Citation71–Citation74 Alternatively or additionally, obesity may reflect abnormalities in energy expenditure as women with PCOS have been found to have reduced resting metabolic rate (1659 kJ/day)Citation75 and reduced thermic effect of food (42 kJ/meal, equivalent to weight gain of 1.9 kg/year).Citation76 Psychological factors are consistent correlates of poor weight management;Citation77 as will be described presently, women with PCOS have relatively more anxiety and depression, and relatively poor self-esteem, body image and quality of life (QoL), compared to their peers.Citation78

Obesity is one of the strongest risk factors for OSA,Citation79 attributable to anatomical changes of the upper airways and thoracic region.Citation80 Longitudinal studies of men and women demonstrate that a 10% increase in body weight predicts a sixfold increase in risk of developing moderate-to-severe sleep-disordered breathing.Citation81 When obesity is severe (BMI >40 kg/m2), the prevalence of OSA in men and women is as great as 92%.Citation82

There is evidence that obesity contributes to sleep disturbances beyond OSA.Citation83 Several studies have shown that obesity is associated with objectively assessed daytime sleepiness and subjective reports of fatigue, independently of OSA.Citation84,Citation85 Vgontzas et alCitation83 have proposed two possible mechanisms through which obesity produces these sleep disturbances. In one pathway, shorter sleep duration and subjective fatigue in obese individuals is related to psychological distress and upregulation of the HPA axis. In the second pathway, in which sleep duration is not altered, metabolic parameters such as insulin resistance as well as lack of physical activity are invoked, with normal- or downregulation of the HPA axis. Both pathways are proposed to be associated with hypercytokinemia.Citation83

There is some evidence that obesity directly contributes to OSA among women with PCOS, although, as highlighted previously, it does not fully account for findings from community- and clinic-based studies. For example, high BMI in women with PCOS (n = 53) has been associated with elevated risk of OSA and daytime sleepiness.Citation54 In a study of women with (n = 44) and without (n = 34) PCOS, obesity was the strongest predictor of sleep apnea risk (as measured by the Berlin questionnaire),Citation86 in contrast to another study of obese women with PCOS (n = 23), among whom there was no relationship between the degree of obesity and sleep apnea severity (as per AHI).Citation87

On balance, the evidence supports contributions to sleep disorders both of PCOS and obesity. From the perspective of stress, the former is metabolic while the latter is oxidative, which might aggravate sleep harmonically,Citation25 but studies that examine this are lacking.

Hyperandrogenemia

The prevalence of OSA differs by sex, with obese women having lower risk compared to males of similar BMI.Citation88 Men and women often have different clinical presentations for OSA. For example, when matched for age, BMI, AHI and EDS score, women were less likely than men to present with witnessed apnea but more likely to report insomnia.Citation89 Differences between men and women may be due to differences in the anatomy of the upper airway, sex hormones and/or central adiposity.Citation90,Citation91

Women with PCOS commonly have increased testosterone (free and bound) and androstenedione, and hyperandrogenemia is a diagnostic criterion. Excess androgen is known to induce changes in body composition, including increased central adiposity. In women with PCOS, serum androgen levels are positively correlated with waist–hip ratio, independent of obesity.Citation92 Androgen-induced changes to central adiposity, rather than increased weight overall, may contribute to OSA in these women.

This proposition is supported by work showing that among obese women with PCOS (n = 18), the severity of OSA was correlated with both the degree of androgen excess and waist–hip ratio.Citation50 Similarly, among nonobese women with (n = 18) and without (n = 10) PCOS, who did not have OSA, AHI during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep was correlated with total testosterone.Citation55 An inconsistent finding has been reported for a group of women with PCOS (n = 44) in whom risk of OSA was determined by the Berlin questionnaire.Citation86

Few studies have investigated the potential role of hyperandrogenemia in other forms of sleep disturbance in women. Mixed findings about androgens and sleep architecture have been reported from polysomnographic studies of adolescent girls with PCOS.Citation56,Citation93

Insulin resistance

There is considerable evidence for a relationship between sleep disturbances and insulin resistance, with numerous studies demonstrating that sleep restriction and/or sleep disorders can exacerbate insulin resistance.Citation94–Citation96 Insulin resistance may also have a role in the development of sleep disturbances. For example, in a cross-sectional study of risk factors for EDS (n = 1741) undertaken in the US, diabetes (fasting glucose >126 mg/dL) was strongly associated with EDS.Citation84 Similarly, in a small study of men with OSA, those with EDS (n = 22) had higher plasma insulin levels and insulin resistance compared with those without EDS (n = 22) when matched for age, BMI, and AHI.Citation97 A prospective study of incident OSA in a population-based sample of French men and women (n = 3565) also demonstrated that fasting hyperinsulinemia predicted development of OSA, independently of BMI.Citation98

The mechanisms by which insulin resistance may lead to OSA or EDS are unknown. Evidence from animal and human studies has demonstrated that insulin increases sympathetic outflow,Citation99,Citation100 which may in turn affect sleep architecture and the risk of sleep-disordered breathing and daytime sleepiness.

In a polysomnographic study of women with (n = 53) and without (n = 452) PCOS, Vgontzas et al found that insulin resistance was the strongest risk factor for sleep apnea, before and after controlling for age, BMI, and free and total testosterone levels.Citation54 Similar findings were reported in another study of women with PCOS (n = 40), with higher fasting insulin levels observed among those with elevated risk of OSA (as per Berlin questionnaire).Citation52

If insulin resistance causes sleep disturbances, then treatment with insulin sensitizers should be mitigating. Adolescent girls with PCOS who received metformin treatment reported reduced sleep disturbances and daytime sleepiness, but it is not possible to distinguish between effects of improved insulin resistance and the concomitant reductions in BMI and hyperandrogenemia.Citation101 In a recent pilot for a randomized placebo-controlled trial, nondiabetic individuals with insulin resistance and OSA (n = 45) were allocated to receive either pioglitazone or placebo. Pioglitazone produced no improvement in OSA symptoms or other measures of sleep quality, despite significant improvements in insulin sensitivity.Citation102 Thus, there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about this matter, and we recommend further research.

Cortisol

In a recent longitudinal study of obese girls aged 13–16 years with (n = 20) and without PCOS (n = 20), the role of the steroid metabolome was investigated. No difference in morning cortisol concentration was found between the two groups, although levels were twice as high as those reported in studies of girls of normal weight.Citation103 Furthermore, weight loss was associated with a decrease in cortisol whether or not the girls had PCOS. Together, this suggests that the adrenal stimulation was attributable to obesity rather than to PCOS.

Findings concerning women with PCOS are somewhat contradictory. In one study (n = 21 with PCOS, 11 overweight/obese; n = 10 without PCOS, none overweight/obese), 24-hour cortisol profiles were obtained. While there was no difference in mean 24-hour cortisol levels overall, women with PCOS had lower night-time cortisol levels compared to controls, and this was most pronounced for the women with PCOS who were not overweight/obese.Citation104 In another study, evening, but not morning, plasma cortisol levels were higher in women with PCOS (n = 40) compared to women of similar age and BMI without PCOS (n = 55).Citation105 It is possible that elevated cortisol levels among women with PCOS reflect high BMI, as one study showed that concentration and profiles of cortisol excretion were similar for obese women with (n = 15) and without (n = 15) PCOS.Citation106

Complete HPA function in women with PCOS has not been described. Any changes – whether due to PCOS or associated obesity – are relevant, as dysfunction of the HPA axis at any level impacts on sleep, including increased sleep fragmentation, decreased slow wave sleep, and shortened sleep time.Citation107

There is evidence that women with PCOS have a heightened physiological response to emotional stress. When exposed to an experimental stressor, women with PCOS (n = 32) had higher levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone immediately and 15 minutes post-stress, and higher serum cortisol level 15 minutes post-stress, compared to women without PCOS (n = 32), matched for age and BMI. This was despite the emotional response (state anxiety) reported by the two groups being similar.Citation108

Sleep deprivation is itself a stressor and is associated with elevated cortisol levels.Citation109 It is therefore possible that a bidirectional relationship exists between stress-related hyperactivity of the HPA axis and sleep disturbances in women with PCOS.Citation110

Melatonin

A study of melatonin secretion over 24 hours in women with PCOS has not been undertaken. Melatonin from a single blood sample taken between midnight and 4 am was higher among women with PCOS (n = 50) compared to controls (n = 50).Citation111 Two studies have demonstrated elevated 24-hour urinary 6-sulphatoxymelatonin (the primary metabolite of melatonin) in women with PCOS (n = 22 in the first and n = 24 in the second study) compared to controls (n = 35 and n = 26, respectively).Citation112,Citation113

However, the changes in melatonin described in women with PCOS are unlikely to result in the profound sleep disturbances that have been reported in this subpopulation, particularly given 6-sulphatoxymelatonin was not found to be correlated with sleep efficiency.Citation113 A strong correlation between melatonin obtained from a single blood sample (as above) and testosterone was found in women with PCOS,Citation111 and melatonin was reduced after hyperandrogenemia was attenuated by cyproterone acetate-ethinyl estradiol treatment.Citation114 This suggests that elevated melatonin levels described in women with PCOS may be a result of androgen excess. Conversely, chronic administration of melatonin to women with PCOS (2 mg per day for six months) significantly decreased testosterone levels and reduced menstrual irregularities,Citation115 suggesting that supraphysiological levels of melatonin can reduce androgen levels.

Psychosocial aspects of PCOS and association with sleep

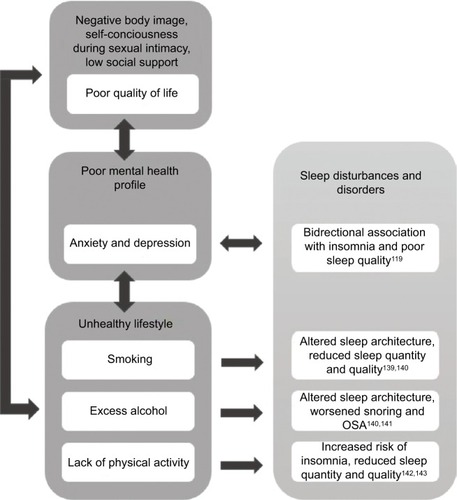

A number of psychosocial aspects of PCOS are likely to contribute to sleep disorders and disturbances in affected women. These are summarized in .

Figure 4 Summary of psychosocial and behavioral factors that are common among women with PCOS and their potential contribution to sleep disturbances and disorders.

Mental health profiles of women with PCOS

Anxiety and depression are well recognized to be associated with sleep disorders.Citation116–Citation118 A systematic review of nine longitudinal studies found suggestive, though not definitive, evidence of a bidirectional relationship.Citation119 A recent study of young women (n = 171) followed over two weeks found reciprocal dynamics between anhedonic depression and disrupted sleep to be especially potent.Citation120

Anxiety and depression are elevated in women with PCOS, with consistent evidence presented in several systematic reviews with meta-analysis.Citation121–Citation125 In our community-based sample, among women with PCOS (the majority of whom had not previously been diagnosed), 50% had symptoms consistent with clinical depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) compared with 30% of their peers.Citation48

In one of the above systematic reviews,Citation125 clinical symptoms, including hirsutism, obesity, and infertility, were shown to contribute to higher emotional distress in women with PCOS, but did not fully account for the disparity. Elevated androgens have been associated with negative affect and depressive symptoms in women with PCOS,Citation78,Citation126 but the relationship between androgens and mood disorders in women remains controversial.Citation124,Citation127 As discussed, women with PCOS may have hyperresponsivity of the HPA axis, which is associated with impaired mental health, including depression.Citation128

In the community-based cohort of Australian women that we undertook, as mentioned, difficulty falling asleep and difficulty maintaining sleep were twice as common in women with PCOS compared to peers of similar age.Citation48 Depressive symptoms mediated both associations, but to varying degrees.

In a clinical sample of women with PCOS (n = 114), those with a history of depression had a threefold increase in disturbed sleep (as per the Patient Health Questionnaire).Citation129 In another study, women with (n = 30) and without PCOS (n = 30), matched for age and BMI, were recruited by advertisement in a Swedish community.Citation130 Symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported (using subscales of the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale for Affective Syndromes). Over 60% of women with PCOS had anxiety symptoms above a cut-point corresponding to clinical relevance, compared to 13% of controls, with the specific symptom of reduced sleep prominent.

As with anxiety and depression, it is likely that a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep and QoL.Citation131 This may be especially so in people with medical conditions.Citation132

QoL for girls and women with PCOS appears to be poorer than for their peers, although less is known about this than about specific conditions such as depression and anxiety. A systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies showed that women with PCOS had lower scores than their counterparts on all domains assessed by the Short Form-36 Health Survey, including physical and social function.Citation133 A recent systematic reviewCitation134 of QoL in adolescents and young women with PCOS identified nine studies that were too diverse in approach for meta-analysis to be performed. However, all studies reported a negative association between PCOS and QoL, with body weight issues conspicuous.

Distressing symptoms of PCOS are likely to contribute to poor QoL. In women more broadly, a systematic review with meta-analysis has demonstrated the profound impact of infertility on QoL.Citation135 Other stressors experienced by women with PCOS – that have received less attention – may contribute, including negative body image, poor self-esteem, poor sexual relations, reduced social support and low social engagement.Citation136–Citation138

Lifestyle and health behaviors

Lifestyle factors and health behaviors, including smoking, consumption of alcohol and lack of physical activity, can contribute to impaired sleep. Tobacco smoking has been associated with altered sleep architecture, short sleep duration and poor-quality sleep, based on both self-reports and polysomnography.Citation139,Citation140 In nonalcoholics, the effect of alcohol consumption on sleep varies during the night, at first decreasing sleep latency and increasing the quality and quantity of NREM sleep, then as alcohol is metabolized, reducing NREM and fragmenting sleep.Citation140,Citation141 Alcohol is also associated with exacerbation of snoring and OSA.Citation140 Physical inactivity has been associated with reduced self-reported hours of sleepCitation142 and increased risk of clinically diagnosed insomnia.Citation143 Furthermore, there is evidence that increased physical activity improves sleep quality.Citation144,Citation145

There is some evidence that lifestyles and behaviors of women with PCOS are less healthy than those of other women of similar age and socioeconomic status. For example, in a case series of women with PCOS presenting at a reproductive health clinic, around half smoked cigarettes, substantially more than expected based on their demographic profile.Citation146 Consistent with this, in the US 2002 National Health Interview Survey, women who reported menstrual-related problems were shown to be more likely than others to smoke and drink heavily.Citation147

Women with PCOS are less physically active than other women and may have difficulty in sustaining engagement in physical activity over the long term.Citation148 When interventions to improve physical activity among women with PCOS have been trialed, attrition rates have been high.Citation149 Barriers contributing to low physical activity in women with PCOS include lack of confidence in the ability to maintain activity, fear of injury and physical limitations.Citation148 It is also possible that there are physiological reasons for impaired exercise capacity in women with PCOS. For example, it has been shown that sedentary normal-weight women with PCOS (n = 14) have impaired cardiorespiratory capacity (maximal oxygen consumption and submaximal ventilatory thresholds) compared to age- and BMI-matched sedentary women without PCOS (n = 14).Citation150

Long-term cardiometabolic consequences of sleep disturbances in PCOS

There are few long-term studies of women with PCOS, with information especially lacking after menopause. However, available evidence suggests that women with PCOS may have relatively early onset of type 2 diabetes and other cardiometabolic disorders. This is not accounted for by the higher prevalence of obesity among women with PCOS, as highlighted in the studies described here. Drawing on wider literature, it is possible that sleep disorders may contribute to deterioration in the heath of women with PCOS, although this has not been studied directly.

Detailed cardiovascular profiles of around 1000 women were obtained across 20 years in the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study undertaken in the US, commencing when participants were aged 18–30 years. Information on PCOS symptoms obtained 16 years from baseline was combined with androgen data from year 2 to classify women as having PCOS or not. Using data from year 5, women with PCOS (n = 42) had higher left ventricular mass index and larger left arterial diameter.Citation151 By year 16, when women were aged 34–46 years, PCOS was associated with a twofold increase in incident diabetes (with almost a quarter of women with PCOS affected) and a twofold increase in dyslipidemia. Among women with normal BMI, those with PCOS (n = 31) had three times the rate of diabetes compared to those without PCOS.Citation152 At year 20, women with PCOS (n = 55) had increased coronary artery calcification and intima-media thickness.Citation153

Australian hospital admission data from 1980 to 2011 have been used to compare 2566 women with a recorded diagnosis of PCOS to 25,660 age-matched women (identified using the electoral roll); most women in this study were aged under 40 years. Women with a diagnosis of PCOS were two to three times more likely to be hospitalized for adult-onset diabetes, hypertensive disorders, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease compared to women without PCOS. These findings remained statistically significant after adjusting for obesity.Citation154

In a retrospective cohort study, women with PCOS (n = 319) identified through hospital records were compared with age-matched women (n = 1060) identified through general practice records. After an average follow-up of 31 years, when approximately 80% of women were postmenopausal, those with PCOS had elevated prevalence of diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol.Citation155 Another study with a small sample size and substantial losses to follow-up over 21 years found more hypertension and higher triglycerides in women with PCOS (n = 25 of 35) compared to women of similar age and BMI (n = 68 of 120).Citation156

Turning to the wider literature, a recent meta-analysis of cohort studies showed that OSA was associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes after adjustment for age, sex and BMI (RR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.27–1.75, eight studies, 63,647 participants).Citation157 Other types of sleep disturbance were also associated with type 2 diabetes, notably – in view of our findings on women with PCOSCitation48 – difficulty initiating sleep (RR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.23–1.95) and difficulty maintaining sleep (RR = 1.72, 95% CI 1.45–2.05).

Sleep restriction has been demonstrated to result in increased food intake due to increased appetite, exceeding the energy amount needed to meet the requirements of extended wakefulness, and thereby resulting in weight gain.Citation158–Citation160 It has also been shown to decrease the ability to lose body fat with dietary restriction,Citation158,Citation161 and to alter glucose metabolism, with decreases in glucose clearance, insulin sensitivity and acute insulin response documented.Citation158,Citation162,Citation163

OSA is likely to increase the risk of diabetes through intermittent hypoxia and arousals, which result in impaired glucose tolerance through increasing sympathetic nervous system activity, HPA axis dysregulation, altered cytokine release and oxidative stress.Citation164–Citation167 OSA is also independently associated with hypertension, premature atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness and an increased risk of future myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular mortality.Citation166,Citation168,Citation169 This may be due to the combination of sympathetic nervous system stimulation and endothelial dysfunction that result from OSA.Citation170,Citation171

In studies of short duration, insulin–glucose metabolism and lipids are worse in women with PCOS who have OSA than among women with PCOS but not OSA, independent of BMI.Citation52,Citation54,Citation59,Citation172 A link between sleep disturbances and poor long-term cardiometabolic health among women with PCOS remains speculative, as direct evidence is lacking.

Management of sleep disturbances in PCOS

Referral to a sleep specialist allows diagnosis of clinical conditions such as OSA and insomnia, and subsequent treatment. OSA is generally diagnosed using overnight polysomnography to generate AHI.Citation40 Insomnia diagnosis ideally requires assessment by a clinical psychologist.Citation173 However, many sleep medicine clinics do not currently have the resources necessary for adequate diagnosis, such as the ISI questionnaire, sleep diaries and measures of daytime fatigue without sleepiness. It important to recognize that OSA and insomnia are frequently comorbid,Citation173 and also that women with PCOS may have other forms of sleep disturbance.

Weight loss is generally recommended for overweight and obese people with OSA,Citation40 although recent research has indicated that weight loss may only decrease the severity of OSA in a minority of patients.Citation174 As described above, weight loss may be particularly difficult to achieve in many women with PCOS due to hormonal abnormalities and other factors. Weight loss in women with PCOS would improve insulin sensitivity and symptom profiles, including fertility, so research is needed to understand the type and intensity of support required to achieve this. Avoidance of alcohol and sedative medications, which may predispose the upper airway to collapse, is also frequently recommended for OSA.Citation40 Again, this poses a particular difficulty for women with PCOS in view of their anxiety and use of alcohol, possibly as a coping mechanism.Citation175

In cases of mild OSA, oral appliances, commonly known as mandibular advancement splints, which are custom-made to increase upper airway size and reduce the likelihood of airway collapse during sleep, may be recommended.Citation40 However, efficacy and acceptability of oral appliances in women with PCOS is yet to be explored.

A small amount of research has been conducted in women with PCOS about the benefits of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment, involving wearing a mask over the nose during sleep to maintain airway patency. CPAP has been shown to be a promising treatment for OSA in young obese women with PCOS, with improvements in insulin sensitivity, daytime diastolic blood pressure, and cardiac sympathovagal balance after eight weeks of treatment.Citation176 These results indicate the need for a larger, well-designed randomized controlled trial to assess the clinically relevant effects of CPAP treatment on markers of future cardiovascular risk in women with PCOS.Citation177

For the general OSA subpopulation (mostly men), there is now evidence from systematic reviews with meta-analysis that CPAP reduces blood pressureCitation178 and endothelial dysfunction, which promote the development of atherosclerosis.Citation179,Citation180 Thus, CPAP could have a role in primary prevention of vascular disease, despite recent findings that CPAP is not effective in reducing coronary events in those with preexisting vascular disease.Citation181 Systematic reviews with meta-analysis have also indicated that insulin resistance can be improved with CPAP use, thereby possibly reducing the risk of development of type 2 diabetes in nondiabetic and prediabetic individuals.Citation18

Importantly for women with PCOS, a systematic review with meta-analysis has provided evidence that CPAP treatment reduces depressive symptoms.Citation182 A subsequent large, randomized controlled trial of over 2000 individuals with moderate-to-severe OSA and coronary or cerebrovascular disease demonstrated that CPAP was effective in increasing QoL as well as decreasing symptoms of depression and anxiety.Citation183

The American College of Physicians now recommends cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) as the most appropriate treatment for all adults with insomnia.Citation184 This treatment is also recommended as a first-line treatment for insomnia by the British Association for Psychopharmacology.Citation185 The efficacy of CBT in treating insomnia symptoms has been demonstrated in multiple systematic reviews with meta-analyses,Citation186–Citation189 but most sleep clinics do not have clinical psychologists available to provide this treatment. In view of the widespread mental health and other problems reported among women with PCOS, there is a good case for referral to a clinical psychologist who can assess and address problems holistically.

In recent years, trials have been undertaken to assess the efficacy of online delivery of CBT for insomnia, using highly structured internet programs as a means of overcoming the barriers to face-to-face delivery of treatment.Citation190 A recent systematic review with meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials of internet CBT for insomnia found evidence of clinically significant improvements in symptoms, of the order achieved in face-to-face CBT.Citation190 Importantly, the ISI score of patients was found to be reduced overall by 21%,Citation190 and by 15% in a similar systematic review with meta-analysis.Citation191 This option may appeal to women with PCOS as cost-effective, but they should still be encouraged to consult a clinical psychologist or other professional support services for wider problems.

There are well-recognized hazards in using pharmacotherapy for the primary treatment of insomnia. Depending on the type of drug used, negative effects include carry-over daytime sedation, slowed reactions and memory impairment, as well as the potential for intensification of symptoms upon cessation of treatment.Citation173 Pharmacotherapy is only recommended short term.Citation192 This is particularly pertinent for women with PCOS whose insomnia and other sleep disturbances are unlikely to be short term and are related to underlying factors that need to be addressed directly.

Women who experience sleep disturbances, but do not meet the criteria for clinical diagnosis of a sleep disorder, may benefit from sleep hygiene approaches. This includes behavioral and environmental recommendations for promoting sleep.Citation193 Avoidance of smoking and alcohol and regular physical activity are aspects of sleep hygiene that have already been described. Other recommendations include avoidance of caffeine, adhering to regular sleep and wake times and stress management.Citation193 Stress management techniques, such as mindfulness, have been shown to reduce presleep arousal and worry,Citation194 which may be beneficial for women with PCOS. Clinical anxiety requires psychological expertise, however.

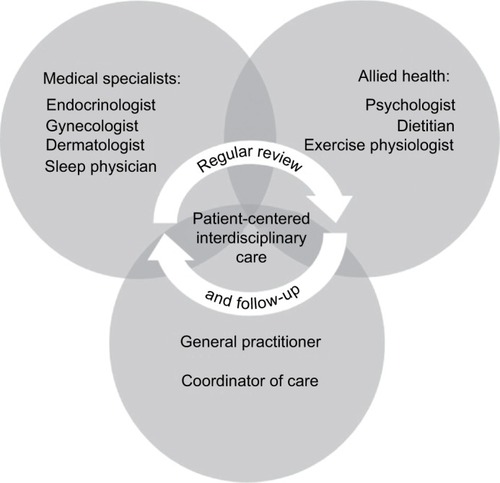

As has been highlighted throughout this review, it is common for women with PCOS to experience symptoms that span multiple medical specialties. The management of sleep disturbances among women with PCOS should form part of an interdisciplinary model of care (summarized in ) with effective communication between care providers.Citation195 It is important that interdisciplinary care is patient-centeredCitation195 and emphasizes a holistic approach to health and well-being.

Figure 5 Model of interdisciplinary care recommended for management of sleep disturbances and disorders in women with PCOS.

Abbreviation: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Conclusion

There is mounting evidence for an association between PCOS and sleep disturbances that is complex and possibly bidirectional. This is not simply due to the tendency of women with PCOS to be obese, as associations are seen in PCOS women of normal weight and most associations are upheld after adjustment for BMI. This suggests poor sleep is part of the pathophysiology of PCOS. We view PCOS as a condition of severe metabolic stress that cascades into oxidative and emotional stress. We suggest that multidimensional treatment, including treatment to improve sleep, may improve metabolic function and could potentially prevent long-term cardiometabolic sequelae for these women.

We have identified some important gaps in the literature, with further research recommended. These include a need to fully describe HPA function in women with PCOS, and for further trials of insulin sensitizers and interventions designed to overcome the specific difficulties that women with PCOS have in sustaining physical activity. The implications for sleep deserve specific attention as well as the possibility that bidirectional processes can be harnessed so that improved sleep reduces metabolic stress in women with PCOS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Champion, Ph.D., and Alice Rumbold, Ph.D., for assistance with summarizing relevant literature. Dr JC Avery was supported by a fellowship from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre for Research Excellence in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Prof RD McEvoy is the recipient of an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RoeAHDokrasAThe diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescentsRev Obstet Gynecol201142455122102927

- SteinIFLeventhalMLAmenorrhea associated with bilateral polycystic ovariesAm J Obstet Gynecol1935292181191

- Diamanti-KandarakisEDunaifAInsulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implicationsEndocr Rev2012336981103023065822

- El HayekSBitarLHamdarLHMirzaFGDaoudGPolycystic ovarian syndrome: an updated overviewFront Physiol2016712427092084

- JavedAKumarSSimmonsPSLteifANPhenotypic characterization of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents based on menstrual irregularityHorm Res Paediatr201584422323026184981

- HousmanEReynoldsRVPolycystic ovary syndrome: a review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestationsJ Am Acad Dermatol2014715847.e841847.e81025437977

- SivayoganathanDMaruthiniDGlanvilleJMBalenAHFull investigation of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) presenting to four different clinical specialties reveals significant differences and undiagnosed morbidityHum Fertil2011144261265

- LujanMEChizenDRPiersonRADiagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: pitfalls and controversiesJ Obstet Gynaecol Can200830867167918786289

- MarchWAMooreVMWillsonKJPhillipsDINormanRJDaviesMJThe prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteriaHum Reprod201025254455119910321

- ZawadzkiJDunaifADiagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approachDunaifAGivensJHaseltineFMarrianGPolycystic Ovary Syndrome Current Issues in Endocrinology and Metabolism4BostonBlackwell Scientific1992

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop GroupRevised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril20048111925

- AzzizRCarminaEDewaillyDCriteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: an Androgen Excess Society GuidelineJ. Clin Endocrinol Metab200691114237424516940456

- MoranLTeedeHMetabolic features of the reproductive phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod Update200915447748819279045

- BraceroNZacurHAPolycystic ovary syndrome and hyperprolactinemiaObstet Gynecol Clin North Am2001281778411293005

- FilhoRBDominguesLNavesLFerrazEAlvesACasulariLAPolycystic ovary syndrome and hyperprolactinemia are distinct entitiesGynecol Endocrinol200723526727217558684

- SuHWChenCMChouSYLiangSJHsuCSHsuMIPolycystic ovary syndrome or hyperprolactinaemia: a study of mild hyperprolactinaemiaGynecol Endocrinol2011271556220504100

- SzoslandKPawlowiczPLewinskiAProlactin secretion in poly-cystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)Neuro Endocrinol Lett20153615358

- ChenLKuangJPeiJHContinuous positive airway pressure and diabetes risk in sleep apnea patients: a systemic review and meta-analysisEur J Intern Med201739395027914881

- EhrmanDABarnesRBRosenfieldRLPolycystic ovary syndrome as a form of functional ovarian hyperandrogenism due to dysregulation of androgen secretionEndocr Rev19951633223537671850

- ChristakouCDiamanti-KandarakisEPolycystic ovary syndrome—phenotypes and diagnosisScand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl2014244182225083888

- TosiFFiersTKaufmanJMImplications of androgen assay accuracy in the phenotyping of women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2016101261061826695861

- SteptoNKCassarSJohamAEWomen with polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clampHum Reprod201328377778423315061

- RajkhowaMBrettSCuthbertson DanielJInsulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with defective regulation of ERK1/2 by insulin in skeletal muscle in vivoBiochem J2009418366567119053948

- CaroJFDohmLGPoriesWJSinhaMKCellular alterations in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue responsible for insulin resistance in obesity and type II diabetesDiabetes Metab Rev1989586656892693017

- Diamanti-KandarakisEPapalouOKandarakiEAKassiGMechanisms in endocrinology: nutrition as a mediator of oxidative stress in metabolic and reproductive disorders in womenEur J Endocrinol20171762R79R9927678478

- UrbanekMLegroRSDriscollDAThirty-seven candidate genes for polycystic ovary syndrome: strongest evidence for linkage is with follistatinProc Natl Acad Sci U S A199996158573857810411917

- JonesMRGoodarziMOGenetic determinants of polycystic ovary syndrome: progress and future directionsFertil Steril20161061253227179787

- WitchelSFRecabarrenSEGonzálezFEmerging concepts about prenatal genesis, aberrant metabolism and treatment paradigms in polycystic ovary syndromeEndocrine201242352653422661293

- ParkinsonJRHydeMJGaleCSanthakumaranSModiNPreterm birth and the metabolic syndrome in adult life: a systematic review and meta-analysisPediatrics20131314e1240e126323509172

- NewsomeCAShiellAWFallCHPhillipsDIShierRLawCMIs birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism?—a systematic reviewDiabet Med200320533934812752481

- LiSZhangMTianHLiuZYinXXiBPreterm birth and risk of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysisObes Rev2014151080481125073871

- DaviesMJMarchWAWillsonKJGilesLCMooreVMBirth-weight and thinness at birth independently predict symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthoodHum Reprod20122751475148022373955

- KennawayDJFlanaganDEMooreVMCockingtonRARobin-sonJSPhillipsDIThe impact of fetal size and length of gestation on 6-sulphatoxymelatonin excretion in adult lifeJ Pineal Res200130318819211316330

- WardAMMooreVMSteptoeACockingtonRARobinsonJSPhillipsDISize at birth and cardiovascular responses to psychological stressors: evidence for prenatal programming in womenJ Hypertens200422122295230115614023

- Langley-EvansSCNutrition in early life and the programming of adult disease: a reviewJ Hum Nutr Diet201528Suppl 1114

- Langley-EvansSCDevelopmental programming of health and diseaseProc Nutr Soc20066519710516441949

- ReynoldsRMGlucocorticoid excess and the developmental origins of disease: two decades of testing the hypothesis – 2012 Curt Richter Award WinnerPsychoneuroendocrinology201338111122998948

- JenkinsCDStantonBANiemcrykSJRoseRMA scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical researchJ Clin Epidemiol19884143133213351539

- American Psychiatric AssociationSleep-Wake Disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)ArlingtonAmerican Psychiatric Association2013

- ParkJGRamarKOlsonEJUpdates on definition, consequences, and management of obstructive sleep apneaMayo Clin Proc201186654955421628617

- EpsteinLJKristoDStrolloPJJrAdult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep MedicineClinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adultsJ Clin Sleep Med20095326327619960649

- GoelNRaoHDurmerJSDingesDFNeurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivationSemin Neurol200929432033919742409

- LégerDBayonVSocietal costs of insomniaSleep Med Rev201014637938920359916

- HillmanDRLackLCPublic health implications of sleep loss: the community burdenMed J Aust20131998S7S10

- BucksRSOlaitheMEastwoodPNeurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-reviewRespirology2013181617022913604

- LinTYLinPYSuTPRisk of developing obstructive sleep apnea among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a nationwide longitudinal follow-up studySleep Med20173616516928599952

- HungJHHuLYTsaiSJRisk of psychiatric disorders following polycystic ovary syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort studyPLoS One201495e9704124816764

- MoranLJMarchWAWhitrowMJGilesLCDaviesMJMooreVMSleep disturbances in a community-based sample of women with polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod201530246647225432918

- EzehUYildizBOAzzizRReferral bias in defining the phenotype and prevalence of obesity in polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2013986E1088E109623539721

- FogelRBMalhotraAPillarGPittmanSDDunaifAWhiteDPIncreased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in obese women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20018631175118011238505

- SuriJSuriJCChatterjeeBMittalPAdhikariTObesity may be the common pathway for sleep-disordered breathing in women with polycystic ovary syndromeSleep Med2016233239

- TasaliEVan CauterEEhrmannDARelationships between sleep disordered breathing and glucose metabolism in polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2006911364216219719

- TasaliEVan CauterEHoffmanLEhrmannDAImpact of obstructive sleep apnea on insulin resistance and glucose tolerance in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200893103878388418647805

- VgontzasANLegroRSBixlerEOGrayevAKalesAChrousosGPPolycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role of insulin resistanceJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200186251752011158002

- YangHPKangJHSuHYTzengCRLiuWMHuangSYApnea-hypopnea index in nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndromeInt J Gynaecol Obstet2009105322622919345941

- de SousaGSchluterBMenkeTTrowitzschEAndlerWReinehrTRelationships between polysomnographic variables, parameters of glucose metabolism, and serum androgens in obese adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndromeJ Sleep Res201120347247821199038

- de SousaGSchluterBMenkeTTrowitzschEAndlerWReinehrTA comparison of polysomnographic variables between adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome with and without the metabolic syndromeMetab Syndr Relat Disord20119319119621352077

- de SousaGSchlüterBBuschatzDA comparison of polysomnographic variables between obese adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome and healthy, normal-weight and obese adolescentsSleep Breath2010141333819585163

- NandalikeKAgarwalCStraussTSleep and cardiometabolic function in obese adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndromeSleep Med201213101307131222921588

- BaldwinCMKapurVKHolbergCJRosenCNietoFJSleep Heart Health Study GroupAssociations between gender and measures of daytime somnolence in the Sleep Heart Health StudySleep200427230531115124727

- RedlineSKumpKTishlerPVBrownerIFerretteVGender differences in sleep disordered breathing in a community-based sampleAm J Respir Crit Care Med19941493 Pt 17227268118642

- FranikGKrystaKMadejPSleep disturbances in women with polycystic ovary syndromeGynecol Endocrinol201632121014101727348625

- BorbélyAAA two process model of sleep regulationHum Neurobiol1982131952047185792

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and ResearchColtenHRAltevogtBMSleep physiology Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health ProblemWashingtonNational Academies Press20063353

- HausESmolenskyMBiological clocks and shift work: circadian dysregulation and potential long-term effectsCancer Causes Control200617448950016596302

- DibnerCSchiblerUAlbrechtUThe mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocksAnnu Rev Physiol201072151754920148687

- MorrisCJAeschbachDScheerFACircadian system, sleep and endocrinologyMol Cell Endocrinol201234919110421939733

- GambleKLBerryRFrankSJYoungMECircadian clock control of endocrine factorsNat Rev Endocrinol201410846647524863387

- LimSSDaviesMJNormanRJMoranLJOverweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod Update201218661863722767467

- TeedeHJJohamAEPaulELongitudinal weight gain in women identified with polycystic ovary syndrome: results of an observational study in young womenObesity (Silver Spring)20132181526153223818329

- MoranLJNoakesMCliftonPMGhrelin and measures of satiety are altered in polycystic ovary syndrome but not differentially affected by diet compositionJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20048973337334415240612

- HirschbergALNaessenSStridsbergMBystromBHoltetJImpaired cholecystokinin secretion and disturbed appetite regulation in women with polycystic ovary syndromeGynecol Endocrinol2004192798715624269

- Zwirska-KorczalaKSodowskiKKonturekSJPostprandial response of ghrelin and PYY and indices of low-grade chronic inflammation in lean young women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Physiol Pharmacol200859Suppl 216117818812636

- VrbiklovaJHillMBendlovaBIncretin levels in polycystic ovary syndromeEur J Endocrinol2008159212112718511472

- GeorgopoulosNASaltamavrosADVervitaVBasal metabolic rate is decreased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and biochemical hyperandrogenemia and is associated with insulin resistanceFertil Steril200992125025518678372

- RobinsonSChanSPSpaceySAnyaokuVJohnstonDGFranksSPostprandial thermogenesis is reduced in polycystic ovary syndrome and is associated with increased insulin resistanceClin Endocrinol (Oxf)19923665375431424179

- MoroshkoIBrennanLO’BrienPPredictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literatureObes Rev2011121191293421815990

- MoranLJDeeksAAGibson-HelmMETeedeHJPsychological parameters in the reproductive phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod20122772082208822493025

- SchwartzARPatilSPLaffanAMPolotskyVSchneiderHSmithPLObesity and obstructive sleep apnea: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic approachesProc Am Thorac Soc20085218519218250211

- de SousaAGCercatoCManciniMCHalpernAObesity and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndromeObes Rev20089434035418363635

- PeppardPEYoungTPaltaMDempseyJSkatrudJLongitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathingJAMA2000284233015302111122588

- KositanuritWMunthamDUdomsawaengsupSChirakalwasanNPrevalence and associated factors of obstructive sleep apnea in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgerySleep Breath Epub2017411

- VgontzasANBixlerEOChrousosGPPejovicSObesity and sleep disturbances: meaningful sub-typing of obesityArch Physiol Biochem2008114422423618946783

- BixlerEOVgontzasANLinHMCalhounSLVela-BuenoAKalesAExcessive daytime sleepiness in a general population sample: the role of sleep apnoea, age, obesity, diabetes, and depressionJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059084510451515941867

- VgontzasANBixlerEOTanTLKantnerDMartinLFKalesAObesity without sleep apnoea is associated with daytime sleepinessArch Intern Med199815812133313379645828

- MokhlesiBScocciaBMazzoneTSamSRisk of obstructive sleep apnea in obese and nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and healthy reproductively normal womenFertil Steril201297378679122264851

- GopalMDuntleySUhlesMAttarianHThe role of obesity in the increased of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in patients with polycystic ovarian syndromeSleep Med20023540140414592171

- AkinnusiMESalibaRPorhomayonJEl-SolhAASleep disorders in morbid obesityEur J Intern Med201223321922622385877

- ShepertyckyMRBannoKKrygerMHDifferences between men and women in the clinical presentation of patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeSleep200528330931416173651

- RyanCMBradleyTDPathogenesis of obstructive sleep apneaJ Appl Physiol (1985)20059962440245016288102

- WhittleATMarshallIMortimoreILWraithPKSellarRJDouglasNJNeck soft tissue and fat distribution: comparison between normal men and women by magnetic resonance imagingThorax199954432332810092693

- EvansDJBarthJHBurkeCWBody fat topography in women with androgen excessInt J Obes19881221571623384560

- de SousaGSchluterBBuschatzDThe impact of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenemia on polysomnographic variables in obese adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndromeSleep Breath201216116917521221823

- RaoMNNeylanTCGrunfeldCMulliganKSchambelanMSchwarzJMSubchronic sleep restriction causes tissue-specific insulin resistanceJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201510041664167125658017

- IpMSLamBNgMMLamWKTsangKWLambsKSObstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistanceAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002165567067611874812

- HarschIASchahinSPRadespiel-TrögerMContinuous positive airway pressure treatment rapidly improves insulin sensitivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004169215616214512265

- BarcelóABarbéFde la PeñaMInsulin resistance and daytime sleepiness in patients with sleep apnoeaThorax2008631194695018535117

- BalkauBVolSLokoSHigh baseline insulin levels associated with 6-year incident observed sleep apneaDiabetes Care20103351044104920185739

- GrecoCSpalloneVObstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and diabetes. Fortuitous association or interaction?Curr Diabetes Rev2016122129155

- LansdownAReesDAThe sympathetic nervous system in polycystic ovary syndrome: a novel therapeutic target?Clin Endocrinol (Oxf)201277679180122882204

- El-SharkawyAAAbdelmotalebGSAlyMKKabelAMEffect of metformin on sleep disorders in adolescent girls with polycystic ovarian syndromeJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201427634735225256878

- LiuAKimSHArielDDoes enhanced insulin sensitivity improve sleep measures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot studySleep Med201622576027544837

- ReinehrTKulleARothermelJLongitudinal analyses of the steroid metabolome in obese PCOS girls with weight lossEndocr Connect20176421322428373267

- PrelevicGMWurzburgerMIBalint-PericL24-Hour serum cortisol profiles in women with polycystic ovary syndromeGynecol Endocri-nol199373179184

- KiałkaMOciepkaAMilewiczTEvening not morning plasma cortisol level is higher in women with polycystic ovary syndromePrzegl Lek201572524024226817325

- RoelfsemaFKokPPereiraAMPijlHCortisol production rate is similarly elevated in obese women with or without the polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20109573318332420410226

- BuckleyTMSchatzbergAFOn the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disordersJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059053106311415728214

- BensonSArckPCTanSDisturbed stress responses in women with polycystic ovary syndromePsychoneuroendocrinology200934572773519150179

- MeerloPSgoifoASucheckiDRestricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivitySleep Med Rev200812319721018222099

- GardeAHAlbertsenKPerssonRHansenARuguliesRBidirectional associations between psychological arousal, cortisol, and sleepBehav Sleep Med20121012840

- JainPJainMHaldarCSinghTBJainSMelatonin and its correlation with testosterone in polycystic ovarian syndromeJ Hum Reprod Sci20136425325824672165

- LuboshitzkyRQuptiGIshayAShen-OrrZFutermanBLinnSIncreased 6-sulfatoxymelatonin excretion in women with polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril200176350651011532473

- ShreeveNCagampangFSadekKPoor sleep in PCOS; is melatonin the culprit?Hum Reprod20132851348135323438443

- LuboshitzkyRHererPShen-OrrZUrinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin excretion in hyperandrogenic women: the effect of cyproterone acetate-ethinyl estradiol treatmentExp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes2004112210210715031776

- TagliaferriVRomualdiDScarinciEMelatonin treatment may be able to restore menstrual cyclicity in women with PCOS: a pilot studyReprod Sci Epub201711

- BaglioniCBattaglieseGFeigeBInsomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studiesJ Affect Disord20111351–3101921300408

- GuptaMASimpsonFCObstructive sleep apnea and psychiatric disorders: a systematic reviewJ Clin Sleep Med201511216517525406268

- GlidewellRNMcPherson BottsEOrrWCInsomnia and anxiety: diagnostic and management implications of complex interactionsSleep Med Clin2015101939926055677

- AlvaroPKRobertsRMHarrisJKA systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depressionSleep20133671059106823814343

- KalmbachDAArnedtJTSwansonLMRapierJLCieslaJAReciprocal dynamics between self-rated sleep and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adult women: a 14-day diary studySleep Med20173361228449907

- BarryJAKuczmierczykARHardimanPJAnxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod20112692442245121725075

- BlaySLAguiarJVAPassosICPolycystic ovary syndrome and mental disorders: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysisNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2016122895290327877043

- DokrasACliftonSFutterweitWWildRIncreased risk for abnormal depression scores in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisObstet Gynecol2011117114515221173657

- DokrasACliftonSFutterweitWWildRIncreased prevalence of anxiety symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysisFertil Steril201297122523022127370

- Veltman-VerhulstSMBoivinJEijkemansMJFauserBJEmotional distress is a common risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studiesHum Reprod Update201218663865122824735

- WeinerCLPrimeauMEhrmannDAAndrogens and mood dysfunction in women: comparison of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome to healthy controlsPsychosom Med200466335636215184695

- BlochMDalyRCRubinowDREndocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depressionCompr Psychiatry200344323424612764712

- DedovicKNgiamJThe cortisol awakening response and major depression: examining the evidenceNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2015111181118925999722

- NaqviSHMooreABevilacquaKPredictors of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndromeArch Womens Ment Health20151819510125209354

- JedelEWaernMGustafsonDAnxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass indexHum Reprod201025245045619933236

- ChenXGelayeBWilliamsMASleep characteristics and health-related quality of life among a national sample of American young adults: assessment of possible health disparitiesQual Life Res201423261362523860850

- MedicGWilleMHemelsMEShort- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruptionNat Sci Sleep2017915116128579842

- LiYLiYYu NgEHPolycystic ovary syndrome is associated with negatively variable impacts on domains of health-related quality of life: evidence from a meta-analysisFertil Steril201196245245821703610

- KaczmarekCHallerDMYaronMHealth-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic reviewJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201629655155727262833

- ChachamovichJRChachamovichEEzerHFleckMPKnauthDPassosEPInvestigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: a systematic reviewJ Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol201031210111020443659

- ElsenbruchSHahnSKowalskyDQuality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200388125801580714671172

- PastoreLMPatrieJTMorrisWLDalalPBrayMJDepression symptoms and body dissatisfaction association among polycystic ovary syndrome womenJ Psychosom Res201171427027621911106

- TrentMERichMAustinSBGordonCMQuality of life in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndromeArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2002156655656012038887

- MehariAWeirNAGillumRFGender and the association of smoking with sleep quantity and quality in American adultsWomen Health201454111424261545

- GarciaANSalloumIMPolysomnographic sleep disturbances in nicotine, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, opioid, and cannabis use: a focused reviewAm J Addict201524759059826346395

- ThakkarMMSharmaRSahotaPAlcohol disrupts sleep homeostasisAlcohol201549429931025499829

- ZomersMLHulseggeGvan OostromSHProperKIVerschurenWMPicavetHSJCharacterizing adult sleep behavior over 20 years – the population-based Doetinchem Cohort StudySleep2017407

- ChenLJSteptoeAChenYHKuPWLinCHPhysical activity, smoking, and the incidence of clinically diagnosed insomniaSleep Med20173018919428215247

- Rubio-AriasJÁMarín-CascalesERamos-CampoDJHernandezAVPérez-LópezFREffect of exercise on sleep quality and insomnia in middle-aged women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsMaturitas2017100495628539176

- LangCKalakNBrandSHolsboer-TrachslerEPühseUGerberMThe relationship between physical activity and sleep from mid adolescence to early adulthood. A systematic review of methodological approaches and meta-analysisSleep Med Rev201628324526447947

- NormanRJDaviesMJLordJMoranLJThe role of lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndromeTrends Endocrinol Metab200213625125712128286

- StrineTWChapmanDPAhluwaliaIBMenstrual-related problems and psychological distress among women in the United StatesJ Womens Health (Larchmt)200514431632315916505

- BantingLKGibson-HelmMPolmanRTeedeHJSteptoNKPhysical activity and mental health in women with polycystic ovary syndromeBMC Womens Health20141415124674140