Abstract

The objective of this narrative review paper is to discuss about sleep duration needed across the lifespan. Sleep duration varies widely across the lifespan and shows an inverse relationship with age. Sleep duration recommendations issued by public health authorities are important for surveillance and help to inform the population of interventions, policies, and healthy sleep behaviors. However, the ideal amount of sleep required each night can vary between different individuals due to genetic factors and other reasons, and it is important to adapt our recommendations on a case-by-case basis. Sleep duration recommendations (public health approach) are well suited to provide guidance at the population-level standpoint, while advice at the individual level (eg, in clinic) should be individualized to the reality of each person. A generally valid assumption is that individuals obtain the right amount of sleep if they wake up feeling well rested and perform well during the day. Beyond sleep quantity, other important sleep characteristics should be considered such as sleep quality and sleep timing (bedtime and wake-up time). In conclusion, the important inter-individual variability in sleep needs across the life cycle implies that there is no “magic number” for the ideal duration of sleep. However, it is important to continue to promote sleep health for all. Sleep is not a waste of time and should receive the same level of attention as nutrition and exercise in the package for good health.

Introduction

Sleep is increasingly recognized as a critical component of healthy development and overall health.Citation1–Citation3 Healthy sleep comprises many dimensions, including adequate duration, good quality, appropriate timing, and the absence of sleep disorders.Citation4,Citation5 Not getting enough sleep at night is generally associated with daytime sleepiness, daytime fatigue, depressed mood, poor daytime functioning, and other health and safety problems.Citation6–Citation9 Chronic insufficient sleep has become a concern in many countries, given its association with morbidity and mortality.Citation10,Citation11 For example, habitual short sleep duration has been associated with adverse health outcomes including obesity,Citation12 type 2 diabetes,Citation13 hypertension,Citation14 cardiovascular disease,Citation15 depression,Citation16 and all-cause mortality.Citation17 Interest in finding ways to improve sleep patterns of individuals at the population-level standpoint is growing, and experts recommend that sleep should be considered more seriously by public health bodies, ie, given as much attention and resources as nutrition and physical activity.Citation18–Citation20

Guidelines on the recommended amount of sleep needed for optimal health exist; they are a vital tool for surveillance, they help inform policies, they can provide a starting point for intervention strategies, and they educate the general public about healthy sleep behaviors. However, sleep needs may vary from one person to another at any given age across the lifespan. Additionally, some age groups and populations are more likely to report insufficient sleep duration and may be at greater risk for detrimental health outcomes.Citation5,Citation6,Citation11 The objective of this narrative review article is to discuss whether or not an ideal amount of sleep exists for optimal health and how it is impacted by age.

Insufficient sleep across the lifespan

Insufficient sleep has become widespread over the last decades, especially among adolescents.Citation11,Citation21 Both physiological factors and exogenous exposures come into play in explaining insufficient sleep in this age group. Sleep curtailment is often attributed to extrinsic factors, such as artificial light, caffeine use, lack of physical activity, no bedtime rules in the household, and the increased availability of information and communication technologies.Citation22–Citation25 In adolescence, insufficient sleep has also been attributed to intrinsic factors such as pubertal hormonal changes, which is associated with a shift toward an evening chronotypeCitation26 that may also lead to an asynchrony between the biological clock, characterized by a phase delay, and the social clock.Citation27 In adolescents, this biological phase delay combined with the social clock, for which the main synchronizer is the fixed and early school start time, contributes to the observed sleep deficits in this population.Citation27 The conflict between intrinsic and extrinsic factors, biological time and social time, has been indicated to be greater during adolescence than at any other point in our lives.Citation28

Despite some overlap between factors that could explain insufficient sleep among adolescents and adults, such as exposure to artificial light at night, lack of physical activity, caffeine consumption, and poor sleep hygiene, other factors that could specifically be related to insufficient sleep among adults may include but not be limited to work demands, social commitments, health and/or affective problems, and family dynamics (eg, working mothers and children with full agendas).Citation10

In the elderly, sleep patterns and distribution undergoes significant quantitative and qualitative changes. Older adults tend to have a harder time falling asleep and more trouble staying asleep. This period of life is often accompanied by a circadian shift to a morning chronotype, as opposed to the evening chronotype change during adolescence, that results in early bedtime and risetime.Citation29 Research suggests that the need for sleep may not change with age, but it is the ability to get the needed sleep that decreases with age.Citation10 This decreased ability to sleep in older adults is often secondary to their comorbidities and related medications (polypharmacy) rather than normal aging processes per se.Citation30–Citation32 Furthermore, the increased frequency of sleep-related disorders in the elderly population contribute to much of the sleep deficiencies observed in this population.Citation33–Citation36 Inadequate sleep in the elderly could also be related to other factors, such as life changes (eg, retirement, physical inactivity, decreased social interactions), age-related changes in metabolism, and environmental changes (eg, placement in a nursing home).Citation37

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that in the elderly population both short and long sleep are independently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular-related and cancer-related mortality.Citation38 Additionally, adjustments for health conditions in the studies examining the association between sleep duration and mortality risks did not attenuate the strength of the association between long sleep and increased risk of mortality, which suggests that the mechanisms in these associations may differ between long sleep and short sleep duration.Citation38 One possible explanation for this association, between long sleep duration and increased risk of non-communicable diseases related mortality, may be related to the increased prevalence of sleep fragmentation in this population.Citation38,Citation39 While older adults may report long sleep duration, other sleep characteristics, namely sleep architecture and quality, are altered by sleep fragmentation. As the relationship between long sleep duration and increased risk of cardiovascular-related and cancer-related mortality is unique to the elderly population, the causality should be further investigated.

Normative sleep duration values across the lifespan

Sleep–wake regulation and sleep states evolve very rapidly during the first year of life.Citation40 For example, newborns (0–3 months) do not have an established circadian rhythm and therefore their sleep is distributed across the full 24-hour day.Citation41 At 10–12 weeks, the circadian rhythm emerges and sleep becomes more nocturnal between ages 4 and 12 months.Citation42 Children continue to take daytime naps between 1 and 4 years of age, and night wakings are common.Citation43 Daytime naps typically stop by the age of 5 years and overnight sleep duration gradually declines throughout childhood, in part due to a shift to later bedtimes and unchanged wake times.Citation43

Sleep patterns are explained by a complex interplay between genetic, behavioral, environmental, and social factors. Examples of factors that can determine sleep duration include daycare/school schedules, parenting practices, cultural preferences, family routines, and individual differences in genetic makeup. Despite inter-individual differences in sleep duration, international normative data exist to show the normal distribution of sleep duration for different age groups. However, it is important to keep in mind that normative reference values by no means indicate anything about what the ideal or optimal sleep duration should be, ie, the amount of sleep associated with health benefits. Nevertheless, they tell us about what is normal (or not) in the population and provide a valuable yardstick for practitioners and educators when dealing with sleep-related issues.

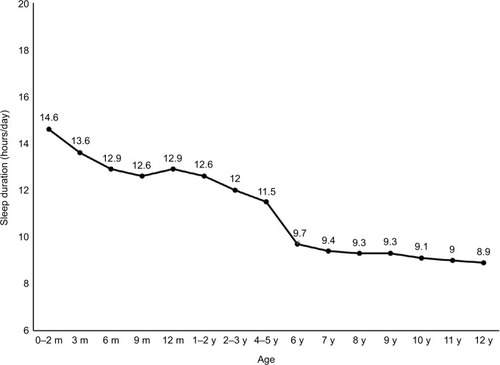

A meta-analysis by Galland et alCitation44 examined the scientific literature with regards to normal sleep patterns in infants and children aged 0–12 years. The review included 69,542 participants from 18 countries and subjective measures were used to determine sleep duration (sleep diary or questionnaire). They calculated mean reference values and ranges (±1.96 SD) for sleep duration of 12.7 h/day (9.0–13.3) for infants (<2 years), 11.9 h/day (9.9–13.8) for toddlers/preschoolers (ages 2–5 years), and 9.2 h/day (7.6–10.8) for children (6–12 years). Normative sleep duration data across age categories are shown in . A strong inverse relationship with age was evident from these data, with the fastest rate of decline observed over the first 6 months of life (10.5 min/month decline in sleep duration). The review also highlighted that Asians had significantly shorter sleep (1 hour less over the 0–12-year range) compared to Caucasians or other ethnic groups. Overall, these reference values should be considered as global norms because the authors combined different countries and cultures.

Figure 1 Normal self-reported sleep durations in children aged 0–12 years.

Abbreviations: m, months; y, years.

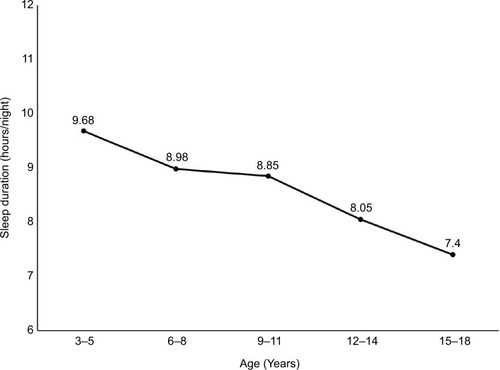

Galland et alCitation45 also reported in 2018 normative sleep duration values for children aged 3–18 years as measured with actigraphy (objective assessment of sleep duration). Their meta-analysis included 79 articles and involved children from 17 countries. As shown in , pooled mean estimates for overnight sleep duration declined from 9.68 hours (3–5 years age band) to 8.98 hours (6–8 years age band), 8.85 hours (9–11 years age band), 8.05 hours (12–14 years age band), and 7.4 hours (15–18 years age band). These normative sleep duration values may aid in the interpretation of actigraphy measures from nighttime recordings in the pediatric population for any given age.

Figure 2 Normal actigraphy-determined sleep duration values in children aged 3–18 years.

A meta-analysis of objectively assessed sleep from childhood to adulthood was also published by Ohayon et alCitation46 in 2004 to determine normative sleep values across the lifespan. A total of 65 studies representing 3,577 healthy individuals aged 5–102 years were included. Polysomnography or actigraphy was used to assess sleep duration in the included studies. They observed that total sleep time significantly decreased with age in adults, while it was the case in children and adolescents only in studies performed on school days. This pattern suggests that, in children and adolescents, the decrease in total sleep time is not related to maturation but to other factors such as earlier school start times.

In summary, normative sleep duration values are helpful in providing information on what constitutes the norm for a given age and what is considered outside the norm. These reference values are impacted by the method used to determine sleep duration (objective vs subjective assessment) and provide norms at the population-level standpoint. Many factors can determine sleep duration at the individual level. Although international normative data provide information about the normal distribution of sleep duration in the population, they do not identify the duration associated with health benefits. For example, having a sleep duration that fits with the average of the population is by no means indicative of either a good or a bad sleep amount. Optimal sleep duration, or the amount of sleep associated with favorable outcomes, is what is used for public health recommendations and is discussed in the next section.

Recommended amount of sleep across the lifespan

In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation in the US released their updated sleep duration recommendations to make scientifically sound and practical recommendations for daily sleep duration across the lifespan.Citation47 The same year, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society released a consensus recommendation for the amount of sleep needed to promote optimal health in adults.Citation48 The year after, they released their recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations.Citation49 Both sleep guidelines issued by the US used a similar developmental approach to deliver their sleep duration recommendations, which included a consensus and a voting process with a multidisciplinary expert panel. The sleep duration recommendations can be found in .

Table 1 Sleep duration recommendations in the US and Canada

Many organizations around the world have their own sleep duration recommendations, and the aim of this article is not to review the different sleep duration guidelines. Overall, they are all very similar, and often reference the recommendations from the US. In Canada, robust and evidence-informed sleep guidelines became available in 2016.Citation50,Citation51 The sleep recommendations in Canada for children of all ages, also known as the 24-hour guidelines, are integrated with physical activity and sedentary behavior recommendations to cover the entire 24-hour period (sleep/wake period). This allows to put more emphasis on the overall “cocktail” of behaviors for a healthier 24-hour day, rather than isolating individual behaviors. This integrated approach to health, with a focus on the interrelationships among sleep, sedentary behavior, and physical activity, is an important advancement in public health messaging. It emphasizes that all of these behaviors matter equally, and balancing all three is required for favorable health outcomes.

The Canadian 24-hour guidelines were the impetus for the development of similar guidelines in Australia,Citation52 New Zealand,Citation53 and the initiation of similar global guidelines by the World Health Organization. Similar integrated 24-hour guidelines for adults and older adults are currently being developed in Canada to cover the entire lifespan. The sleep duration recommendations contained within the 24-hour movement guidelines can be found in .

Although sleep duration recommendations are based on the best available evidence and expert consensus, they are still largely reliant on observational studies using self-reported sleep duration. More longitudinal studies and sleep restriction/extension experiments are needed to better quantify the upper and lower limits of healthy sleep duration, and the shape of the dose–response curve with a wide range of health outcomes. Current sleep duration recommendations also suggest that a generalized optimum exists for the entire population; however, it is unlikely to be the case and this optimum can vary depending on the health outcome examined.Citation54 There is also inter-individual variability in sleep needs in that sleeping shorter or longer than the recommended amount may not necessarily result in adverse effects on health. For example, genetic differences between individuals can explain some of the variability in sleep needs. However, intentionally restricting sleep over a prolonged period of time (ie, chronic sleep deprivation) is not a good idea and can impact health and safety.Citation47 Thus, although sleep recommendations are a good tool for public health surveillance, they need to be adapted on a case-by-case basis in clinic (not a one-size-fits-all recommendation).

Sleep duration recommendations have ranges, or zones of optimal sleep, suggesting that the relationship between sleep duration and adverse health outcomes is U-shaped, with both extremities, sleep durations that are too short or too long, associated with negative effects on health.Citation47–Citation51 There is a large body of evidence providing biological plausibility for short sleep as causally related to a wide range of adverse health outcomes; however, the role of long sleep is less clear. Aside from the elderly population, long sleep is generally associated with other health problems (eg, depression, chronic pain, low socioeconomic status) that can confound the associations.Citation55,Citation56 Reverse causation and residual confounding are thus better mechanisms to explain the associations between long sleep and adverse health outcomes.Citation55,Citation56 This may explain why the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society recommends a threshold value for adults (≥7 hours per night) rather than a range (eg, 7–9 hours per night) (). However, excessive long sleep duration may be informative as it can be indicative of poor sleep efficiency (ie, spending a lot of time in bed but of low quality).

Self-reported sleep duration is typically used in population health surveillance studies, because it provides several advantages (eg, inexpensive, not invasive, and logistically easy to administer to a large sample of individuals). However, the concession is that sleep duration recommendations are then largely based on self-reported data. It is well-known that self-reported sleep duration overestimates actual sleep duration.Citation57 Thus, it would be misleading to use an objective measure of sleep duration to report the prevalence of short sleepers in a given sample; this would result in an overestimation of true short sleepers. The growing popularity of actigraphy and wearable technologies for health behavior tracking in epidemiology is nevertheless desirable for providing better sleep estimates and more precise associations with health outcomes.Citation58,Citation59 Sleep duration recommendations are also likely to evolve over time, as more objective measures of sleep are used in future studies. For example, an individual self-reporting 7 hours of sleep per night may actually get 6 hours if assessed objectively with actigraphy, as it can better account for total sleep by accurately measuring sleep onset and episodes of night wakings.Citation60 Thus, using reliable tools for tracking sleep duration over time is important, and one must keep in mind that the overall sleep duration pattern is more critical to long-term health than one snapshot in time (ie, chronic effect vs acute effect of insufficient sleep on health).

Consumers have also become increasingly interested in using fitness trackers and smartphone applications to assess their sleep. These devices provide information on sleep duration and even sleep quality from in-built accelerometry but the mechanisms and algorithms are propriotery.Citation61–Citation64 The growing body of evidence on consumer sleep tracking devices against polysomnography/actigraphy shows that they tend to underestimate sleep disruptions and overestimate sleep duration and sleep efficiency in healthy individuals.Citation61–Citation64 Although consumer sleep tracking devices are changing the landscape of sleep health and have important advantages, more research is needed to better determine their utility and reduce current shortcomings.Citation61–Citation64

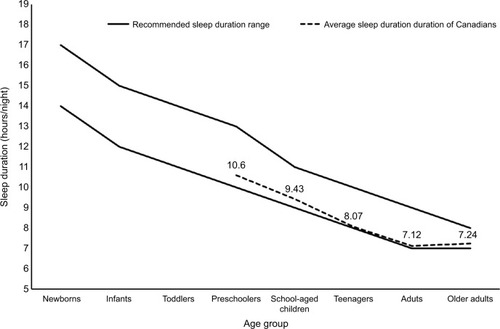

Population statistics in Canada indicate that 16% of preschoolers sleep less than recommended, while 20% of children and one-third of teenagers, adults, and older adults report less-than-recommended sleep durations for optimal health.Citation65–Citation67 These nationally representative surveys use subjective data and are thus comparable to the sleep duration guidelines. As shown in , the average sleep duration of Canadians by age group is situated at the lower border of the sleep duration recommendations. On average, a large proportion of Canadians meet the sleep duration recommendations (eg, two-third of teenagers and adults); however, a large number of individuals fail to meet the guidelines (eg, one-third of teenagers and adults). If we dig deeper, we realize that the teenage group has shown the greatest rate of decline in sleep duration in past decades, especially on school days.Citation11 Knowing the age groups more likely to experience insufficient sleep is critical to help inform the development of interventions aimed at improving sleep (eg, having school start times not earlier than 8:30 am for high-school students).Citation68–Citation70

Figure 3 Sleep duration estimates of Canadians (dashed line) compared with the sleep duration recommendation ranges (solid lines).

Ideal amount of sleep: fact or fiction?

As discussed in this article, there is no magic number for all in terms of the ideal sleep amount to obtain each night. Sleep duration recommendations are meant for public health guidance, but need to be individualized to each patient in the clinic. Sleep needs are determined by a complex set of factors, including our genetic makeup, environmental and behavioral factors. For example, high-performance athletes need more sleep to perform at high level and recover from their intense physical training. Sleep needs in children and adolescents can also be driven by their maturation stage, independent of their chronological age.Citation46 This means that changes in sleep patterns may happen earlier (at a younger age) for some or at an older age for others. Objectively, our current evidence of sleep need is based on circadian, homeostatic, and ultradian processes of sleep regulation and sleep need.

The notion of “optimal sleep” is complex and poorly understood.Citation71 The definitions of optimal sleep also vary in the literature. It is very often defined as the amount recommended by public health authorities. It has also been defined as the daily amount of sleep that allows an individual to be fully awake (ie, not sleepy), and able to sustain normal levels of performance during the day.Citation72 Others have also defined it as the amount of sleep required to feel refreshed in the morning.Citation73 The notion of a new definition to optimal sleep based on performance is of growing interest in the literature. For example, sleep extension interventions have been shown to improve athletic performance.Citation74,Citation75

However, as discussed in this article and by other sleep experts,Citation76 there is no magic number for optimal sleep, and sleep is influenced by inter- and intra-individual factors. Similarly, in a context of sleep deprivation, individual differences in sleep homeostatic and circadian rhythm contributions to neurobehavioral impairments have been elegantly documented by Van Dongen.Citation77–Citation79

Optimal sleep should be conceptualized as the amount of sleep needed to optimize outcomes (eg, performance, cognitive function, mental health, physical health, quality of life, etc). This implies that there might be many dose–response curves that may differ in shape between outcomes.Citation54 Typically, the peaks of each health outcome should fall somewhere within the recommended sleep duration range. However, the exact amount of sleep to get each night for optimizing all relevant health outcomes is not straightforward or ubiquitous as the optimal amount for one outcome may not be the same for another outcome (eg, 9 hours of sleep per night could be the ideal for athletic performance, while 7 hours could be the best for academic achievement). Also, determining the causal effects of sleep need on health is not an easy task and requires experiments (eg, interventional study designs with improved vs reduced sleep, both acutely and chronically applied, and then assessing outcomes on physiology, well-being, health, and behavior).

Although the present article focused on sleep duration, many other dimensions of sleep are important beyond getting a sufficient amount each night. These include aspects of sleep quality such as sleep efficiency (ie, proportion of the time in bed actually asleep), sleep timing (ie, bedtime/wake-up times), sleep architecture (ie, sleep stages), sleep consistency (ie, day-to-day variability in sleep duration), sleep consolidation (ie, organization of sleep across the night), and sleep satisfaction. For example, the National Sleep Foundation recently released evidence-informed sleep quality recommendations for individuals across the lifespan.Citation80 These included sleep continuity variables such as sleep latency, number of awakenings >5 minutes, wake after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency. Along the same lines, monophasic sleep (ie, sleeping once per day, typically at night) is considered the norm in our society but other sleep patterns (eg, biphasic or polyphasic) are also observed depending on the preference of each person or culture. Napping is increasingly seen as a public health tool and countermeasure for sleep deprivation in terms of reducing accidents and cardiovascular events and improving working performance.Citation81

Conclusion

In summary, there is no magic number or ideal amount of sleep to get each night that could apply broadly to all. The optimal amount of sleep should be individualized, as it depends on many factors. However, it is a fair assumption to say that the optimal amount of sleep, for most people, should be within the age-appropriate sleep duration recommended ranges. Future studies should try to better inform contemporary sleep duration recommendations by examining dose–response curves with a wide range of health outcomes. In the meantime, promoting the importance of a good night’s sleep should be a priority given its influence on other behaviors and the well-known adverse consequences of insufficient sleep.Citation82 Important sleep hygiene tips include removing screens from the bedroom, exercising regularly during the day, and having a consistent and relaxing bedtime routine.

Acknowledgments

Jean-Philippe Chaput is a Research Scientist funded by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute (ON, Canada).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChaputJPGrayCEPoitrasVJSystematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youthAppl Physiol Nutr Metab2016416 Suppl 3S266S28227306433

- ChaputJPGrayCEPoitrasVJSystematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years)BMC Public Health201717Suppl 585529219078

- St-OngeMPGrandnerMABrownDSleep duration and quality: impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: a scientific statement from the American Heart AssociationCirculation201613418e36738627647451

- BuysseDJSleep health: can we define it? Does it matter?Sleep201437191724470692

- GruberRCarreyNWeissSKPosition statement on pediatric sleep for psychiatristsJ Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201423317419525320611

- OwensJAdolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequencesPediatrics20141343e921e93225157012

- WolfsonARCarskadonMASleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescentsChild Dev19986948758879768476

- ShochatTCohen-ZionMTzischinskyOFunctional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic reviewSleep Med Rev2014181758723806891

- RoehrsTZorickFSicklesteelJWittigRRothTExcessive daytime sleepiness associated with insufficient sleepSleep1983643193256665394

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and ResearchColtenHRAltevogtBMSleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health ProblemWashington, DCThe National Academies Press2006

- MatriccianiLOldsTPetkovJIn search of lost sleep: secular trends in the sleep time of school-aged children and adolescentsSleep Med Rev201216320321121612957

- WuYZhaiLZhangDSleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesSleep Med201415121456146225450058

- ShanZMaHXieMSleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesDiabetes Care201538352953725715415

- WangYMeiHJiangYRRelationship between duration of sleep and hypertension in adults: a meta-analysisJ Clin Sleep Med20151191047105625902823

- WangDLiWCuiXSleep duration and risk of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studiesInt J Cardiol201621923123927336192

- ZhaiLZhangHZhangDSleep duration and depression among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesDepress Anxiety201532966467026047492

- ShenXWuYZhangDNighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studiesSci Rep201662148026900147

- BarnesCMDrakeCLPrioritizing sleep health: public health policy recommendationsPerspect Psychol Sci201510673373726581727

- ChaputJPDutilCLack of sleep as a contributor to obesity in adolescents: impacts on eating and activity behaviorsInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act201613110327669980

- ChaputJPCarsonVGrayCETremblayMSImportance of all movement behaviors in a 24 hour period for overall healthInt J Environ Res Public Health20141112125751258125485978

- ChaputJPJanssenISleep duration estimates of Canadian children and adolescentsJ Sleep Res201625554154827027988

- BartelKAGradisarMWilliamsonPProtective and risk factors for adolescent sleep: a meta-analytic reviewSleep Med Rev201521728525444442

- ChaputJPTremblayMSKatzmarzykPTSleep patterns and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among children from around the worldPublic Health Nutr201821132385239329681250

- Sampasa-KanyingaHHamiltonHAChaputJPSleep duration and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and energy drinks among adolescentsNutrition201848778129469025

- Sampasa-KanyingaHHamiltonHAChaputJPUse of social media is associated with short sleep duration in a dose-response manner in students aged 11 to 20 yearsActa Paediatr2018107469470029363166

- CarskadonMAVieiraCAceboCAssociation between puberty and delayed phase preferenceSleep19931632582628506460

- KelleyPLockleySWFosterRGKelleyJSynchronizing education to adolescent biology: ‘let teens sleep, start school later’Learn Media Technol2015402210226

- AdanAArcherSNHidalgoMPdi MiliaLNataleVRandlerCCircadian typology: a comprehensive reviewChronobiol Int20122991153117523004349

- EdwardsBAO’DriscollDMAliAJordanASTrinderJMalhotraAAging and sleep: physiology and pathophysiologySemin Respir Crit Care Med201031561863320941662

- FoleyDJMonjanAABrownSLSimonsickEMWallaceRBBlazerDGSleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communitiesSleep19951864254327481413

- FoleyDAncoli-IsraelSBritzPWalshJSleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America SurveyJ Psychosom Res200456549750215172205

- VitielloMVMoeKEPrinzPNSleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adultsJ Psychosom Res200253155555912127171

- Ancoli-IsraelSKripkeDFKlauberMRMasonWJFellRKaplanOPeriodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderlySleep19911464965001798881

- BailesSBaltzanMAlapinIFichtenCSLibmanEDiagnostic indicators of sleep apnea in older women and men: a prospective studyJ Psychosom Res200559636537316310018

- YoungTPaltaMDempseyJSkatrudJWeberSBadrSThe occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adultsN Engl J Med199332817123012358464434

- Ancoli-IsraelSAyalonLDiagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in older adultsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20061429510316473973

- NeikrugABAncoli-IsraelSSleep disorders in the older adult – a mini-reviewGerontology201056218118919738366

- GrandnerMADrummondSPWho are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationshipSleep Med Rev200711534136017625932

- EdwardsBAO’DriscollDMAliAJordanASTrinderJMalhotraAAging and sleep: physiology and pathophysiologySemin Respir Crit Care Med201031561863320941662

- Mclaughlin CrabtreeVWilliamsNANormal sleep in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am200918479981119836688

- DavisKFParkerKPMontgomeryGLSleep in infants and young children: Part one: normal sleepJ Pediatr Health Care2004182657115007289

- SheldonSHSateiaMJCarskadonMASleep in infants and childrenLee-ChiongTLSateiaMJCarskadonMASleep MedicinePhiladelphia, PAHanley and Belfus Inc200299103

- IglowsteinIJenniOGMolinariLLargoRHSleep duration from infancy to adolescence: reference values and generational trendsPediatrics2003111230230712563055

- GallandBCTaylorBJElderDEHerbisonPNormal sleep patterns in infants and children: a systematic review of observational studiesSleep Med Rev201216321322221784676

- GallandBCShortMATerrillPEstablishing normal values for pediatric nighttime sleep measured by actigraphy: a systematic review and meta-analysisSleep2018414

- OhayonMMCarskadonMAGuilleminaultCVitielloMVMeta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespanSleep20042771255127315586779

- HirshkowitzMWhitonKAlbertSMNational Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final reportSleep Health20151423324329073398

- Consensus Conference PanelWatsonNFBadrMSJoint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussionSleep20153881161118326194576

- ParuthiSBrooksLJD’AmbrosioCRecommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep MedicineJ Clin Sleep Med201612678578627250809

- TremblayMSCarsonVChaputJPCanadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleepAppl Physiol Nutr Metab2016416 Suppl 3S31132727306437

- TremblayMSChaputJPAdamoKBCanadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (0–4 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleepBMC Public Health201717Suppl 587429219102

- OkelyADGhersiDHeskethKDA collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines – The Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the early years (Birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleepBMC Public Health201717Suppl 586929219094

- New Zealand Ministry of HealthSit Less, Move More, Sleep Well: Active Play Guidelines for Under-FivesWellingtonNew Zealand, Ministry of Health2017

- MatriccianiLBlundenSRigneyGWilliamsMTOldsTSChildren’s sleep needs: is there sufficient evidence to recommend optimal sleep for children?Sleep201336452753423564999

- StamatakisKAPunjabiNMLong sleep duration: a risk to health or a marker of risk?Sleep Med Rev200711533733917854737

- KnutsonKLTurekFWThe U-shaped association between sleep and health: the 2 peaks do not mean the same thingSleep200629787887916895253

- GirschikJFritschiLHeyworthJWatersFValidation of self-reported sleep against actigraphyJ Epidemiol201222546246822850546

- MeltzerLJMontgomery-DownsHEInsanaSPWalshCMUse of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep researchSleep Med Rev201216546347522424706

- SadehAThe role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: an updateSleep Med Rev201115425926721237680

- CespedesEMHuFBRedlineSComparison of self-reported sleep duration with actigraphy: results from the hispanic community health study/study of Latinos Sueño Ancillary StudyAm J Epidemiol2016183656157326940117

- LorenzCPWilliamsAJSleep apps: what role do they play in clinical medicine?Curr Opin Pulm Med201723651251628820754

- MansukhaniMPKollaBPApps and fitness trackers that measure sleep: Are they useful?Cleve Clin J Med201784645145628628429

- KollaBPMansukhaniSMansukhaniMPConsumer sleep tracking devices: a review of mechanisms, validity and utilityExpert Rev Med Devices201613549750627043070

- KoPRKientzJAChoeEKKayMLandisCAWatsonNFConsumer sleep technologies: a review of the landscapeJ Clin Sleep Med201511121455146126156958

- ChaputJPColleyRCAubertSProportion of preschool-aged children meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines and associations with adiposity: results from the Canadian Health Measures SurveyBMC Public Health201717Suppl 582929219075

- MichaudIChaputJPAre Canadian children and adolescents sleep deprived?Public Health201614112612927931987

- ChaputJPWongSLMichaudIDuration and quality of sleep among Canadians aged 18 to 79Health Rep2017289283328930365

- Adolescent Sleep Working GroupCommittee on Adolescence; Council on School Health. School start times for adolescentsPediatrics2014134364264925156998

- MingesKERedekerNSDelayed school start times and adolescent sleep: A systematic review of the experimental evidenceSleep Med Rev201628869526545246

- HafnerMStepanekMTroxelWMThe economic implications of later school start times in the United StatesSleep Health20173645145729157639

- MatriccianiLBinYSLallukkaTPast, present, and future: trends in sleep duration and implications for public healthSleep Health20173531732328923186

- FerraraMDe GennaroLHow much sleep do we need?Sleep Med Rev20015215517912531052

- Engle-FriedmanMPalencarVRielaSSleep and effort in adolescent athletesJ Child Health Care201014213114120435615

- BonnarDBartelKKakoschkeNLangCSleep interventions designed to improve athletic performance and recovery: a systematic review of current approachesSports Med201848368370329352373

- MahCDMahKEKezirianEJDementWCThe effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball playersSleep201134794395021731144

- HorneJSleepiness as a need for sleep: when is enough, enough?Neurosci Biobehav Rev201034110811819643131

- Van DongenHPBenderAMDingesDFSystematic individual differences in sleep homeostatic and circadian rhythm contributions to neurobehavioral impairment during sleep deprivationAccid Anal Prev201245Suppl111622239924

- Van DongenHPCaldwellJACaldwellJLIndividual differences in cognitive vulnerability to fatigue in the laboratory and in the workplaceProg Brain Res201119014515321531250

- Van DongenHPBelenkyGIndividual differences in vulnerability to sleep loss in the work environmentInd Health200947551852619834261

- OhayonMWickwireEMHirshkowitzMNational Sleep Foundation’s sleep quality recommendations: first reportSleep Health20173161928346153

- FarautBAndrillonTVecchieriniMFLegerDNapping: a public health issue. From epidemiological to laboratory studiesSleep Med Rev2017358510027751677

- ChaputJPThe integration of pediatric sleep health into public health in CanadaSleep Med Epub2018630