Abstract

Self-awakening is the ability to awaken without external assistance at a predetermined time. Cross-sectional studies reported that people who self-awaken have sleep/wake habits different from those of people who use external means to wake from sleep. However, no longitudinal study has examined self-awakening. The present study investigated self- awakening, both habitual and inconsistent, compared to awakening by external means in relation to sleep/wake schedules for five consecutive years in 362 students (starting at mean age 15.1 ± 0.3 years). Students who self-awakened consistently for five consecutive years (5% of all students) went to bed earlier than those who inconsistently self-awakened (mixed group, 40%) or consistently used forced awakening by external means (56%). Awakening during sleep was more frequent and sleep was lighter in the consistently self-awakened group than in the mixed and consistently forced-awakened groups. However, daytime dozing was less frequent and comfort immediately after awakening was greater for the consistently self-awakened group than for the mixed and consistently forced-awakened groups. These results indicate that the three groups have different sleep/wake habits. Previous studies of self-awakening using cross-sectional survey data may have confounded both consistent and inconsistent self-awakening habits. A longitudinal study is necessary to clarify the relationship between the self-awakening habit and sleep/wake patterns.

Introduction

Awakening from sleep is a normal biological response in human beings. There are two kinds of awakening: forced awakening and spontaneous awakening. Forced awakening uses external means such as an alarm. Spontaneous awakening is awakening without external means; it may be divided into natural awakening and self-awakening. Natural awakening is awakening from sleep without an external stimulus at unexpected times, such as during normal nighttime sleep. Self-awakening is awakening at a predetermined time. The present study focuses on self-awakening.

Both the accuracy and success rate of self-awakening have been experimentally examined.Citation1–Citation5 More than half of the people who have the ability to self-awaken successfully awakened within 30 minutes of the predetermined time. For example, seven participants succeeded on nine of 14 days (64%) in a sleep laboratory,Citation2 and 15 participants succeeded on 35 of 44 nights (80%) at their homes.Citation3 Survey studies indicate that many people habitually self-awaken in daily life; for example, 52% of 269 adults (aged 21–84 years)Citation3 and 10.3% of 643 university studentsCitation6 reported habitually self-awakening. People who have a habit of self-awakening in the morning have regular sleep/wake schedules, tended to have a morningness chronotypology, awakened comfortably in the morning, and had less daytime dozing.Citation3,Citation6

However, sleep/wake habits often change, especially in young adults. Therefore, it is necessary to examine whether the habit of self-awakening is a stable habit. The present study investigated the characteristics of sleep/wake habits, subjective sleep qualities, and daytime symptoms in adolescents who had a consistent habit of self-awakening for five consecutive years compared with adolescents who inconsistently self-awakened and others who used forced awakening.

Methods

Participants

Japanese students (N = 379) enrolled at the National College of Technology from 2002–2004 answered a questionnaire for 5 consecutive years each May from 2002–2008. All the students participated voluntarily in this study, and they had the same education level. The data from 362 students (68 females, 294 males) who answered the questionnaire accurately for 5 consecutive years were analyzed. Their mean age at the time of the first investigation was 15.1 ± 0.3 years.

Questionnaires

Habit of self-awakening

Developed on the basis of the work of Moorcroft et alCitation3 and Matsuura et al,Citation6 the following question was used to examine the habit of self-awakening: “How do you usually awaken in the morning?” Participants who chose the following answers were categorized as habitual self-awakening: “I awaken by myself without using an alarm” or “I use an alarm yet awaken before the alarm goes off.” Those who chose the following were categorized as not having the habit of self-awakening: “I use an alarm but sometimes awaken before the alarm goes off.” or “I use an alarm and do not awaken before the alarm goes off.”

Sleep/wake habit, subjective sleep quality, and daytime symptoms

This study used a questionnaire about sleep/wake habits that was developed in a previous survey.Citation7 The questionnaire consisted of 24 items about sleep/wake habits (six items), subjective quality of sleep (five items), daytime symptoms (three items), and others. Items on sleep/wake habits concerned habitual bedtime, wake-up time, and sleep times on weekdays and on weekends. Subjective sleep quality consisted of sleep latency (minutes), number of awakenings after sleep onset, sleep depth (one: deep; five: light), time from awakening to getting out of bed (minutes), and subjective comfort after awakening (one: bad; five: good). The daytime symptoms included number of naps, dozing off, and sleepiness per week.

This questionnaire had been previously conducted with about 5500 Japanese people ranging from infants to individuals of advanced age, and its construct validity was confirmed.Citation7 However, its reliability was not fully confirmed. In the present study, reliability was evaluated by the test-retest method by calculating the Pearson’s product moment correlations between years, such as first and second, second and third, third and fourth, and fourth and fifth years.

Morningness-eveningness (ME) type

A Japanese versionCitation8 of the ME scale was used to evaluate circadian preference.Citation9 The Japanese version of the ME scale has been confirmed to have high reliabilityCitation8 and validity.Citation10 The scale consists of 19 items, and the ME scores are divided into the following five categories: definitely evening type (16–30 points), moderately evening type (31–41 points), intermediate type (42–58 points), moderately morning type (59–69 points), and definitely morning type (70–86 points).

All questionnaire items were used from 2002–2008 except for ME items, which were used from 2002–2007.

Statistical analysis

Students were categorized into the following three groups: the consistently self-awakened group (CSA) comprised those who consistently reported self-awakening for 5 consecutive years. The mixed group (MIX) comprised those who reported self-awakening in some years but did not in other years. The consistently forced-awakened group (CFA) comprised those who consistently reported being awakened by an alarm or other external means for five consecutive years.

A two-way mixed model analysis of variance was performed with group (CSA, MIX, or CFA) and time (first to fifth year) as factors. The degrees of freedom were adjusted by the Huynh–Feldt epsilon. Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni procedure.

Results

The number of students (total N = 362) who had a habit of self-awakening in the first to fifth years was 94 (26%), 67 (19%), 62 (17%), 62 (17%), and 58 (16%), respectively. Overall, only 17 students (5%; twelve males and five females) were classified as CSA. Two hundred and one students (56%; 154 males and 47 females) were classified as CFA. The number of students in the MIX group (144 students; 128 males and 16 females; 40%) that self-awakened in the first, second, third, and fourth year was 78 (54%), 32 (22%), 20 (14%), and 14 (10%), respectively.

The 1-year test-retest correlation coefficients of the questionnaire items on sleep/wake habit, subjective sleep quality, and daytime symptoms ranged from 0.18–0.81 (all P < 0.01). These correlation coefficients were transformed into z′-scores and averaged between first and second, second and third, third and fourth, and fourth and fifth years. The z′-scores were then retransformed into correlation coefficients. Accordingly, the reliability coefficients were 0.43, 0.50, 0.48, and 0.46 between first and second, second and third, third and fourth, and fourth and fifth years, respectively. These values indicate an almost large effect size.Citation11

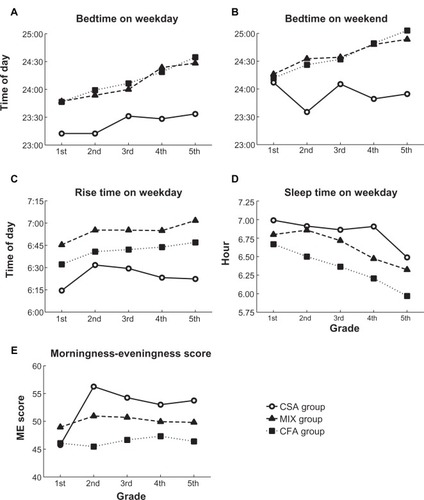

shows the results of the analysis of variance. There were no significant interactions of group by year. Regarding sleep/wake habits ( and ), there were significant main effects of group for bedtime (P < 0.01), wake-up time (P < 0.01), and sleep time (P < 0.001) on weekdays. The CSA group went to bed earlier than both the MIX and CFA groups (P < 0.05), got up earlier than the MIX group (P < 0.05), and slept longer than the CFA group (P < 0.05). The MIX group woke up later (P < 0.01) and slept longer (P < 0.05) than the CFA group. For weekends, the main effect of group for bedtime was also significant (P < 0.05). The CSA group went to bed earlier than the MIX and CFA groups (P < 0.05).

Figure 1 Sleep/wake habits in each group for 5 years.Abbreviations: CFA, consistently forced-awakened group; CSA, consistently self-awakened group; ME, morningness–eveningness; MIX, mixed group.

Table 1 Main effects and interactions of group and year for sleep/wake habit, subjective sleep estimation, and daytime symptoms

Table 2 Parameters of the sleep/wake habit, subjective sleep estimation, and daytime symptoms in each group

There were significant main effects of group for the morningness chronotypology score (P < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the MIX group was higher in morningness than the CFA group (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between the CSA group and the MIX or CFA groups. In , however, it appears that the ME score of the CSA group changed from the first year to the second year. Therefore, a 3 (group: CSA, MIX, or CFA) ×4 (year: 2–5) analysis of variance was performed. The results showed a significant main effect of group (F [2117] = 6.610; P < 0.01). The mean ME scores of the CSA and MIX groups from the second to fifth years were significantly higher than the ME scores of the CFA group (P < 0.05).

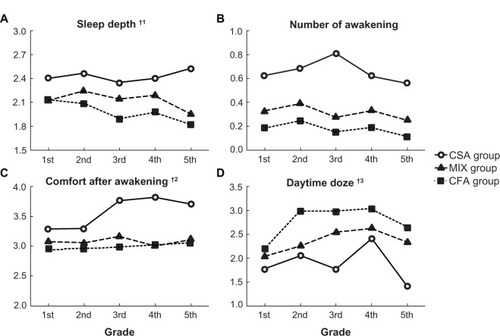

Regarding subjective sleep quality and daytime symptoms, there were significant main effects of group for sleep depth (P < 0.05), number of awakenings after sleep onset (P < 0.001), comfort immediately after awakening (P < 0.05), and daytime dozing (P < 0.05; ). Although the CSA group awakened during sleep more frequently than the MIX (P < 0.05) and CFA groups (P < 0.001; and ) and rated their sleep to be lighter than the CFA group (P < 0.10), they were more comfortable at awakening than the CFA group (P < 0.05). Although the CFA group awakened less frequently than the MIX group during sleep (P < 0.05), they more frequently dozed off in the daytime than the CSA and MIX groups (P < 0.10).

Figure 2 Subjective sleep quality and subjective ratings after awakening for 5 years.Notes:†1response scale: 1 deep, 5 light; †2response scale: 1 very bad, 5 very good; †3number per week.Abbreviations: CFA, consistently forced-awakened group; CSA, consistently self-awakened group; MIX, mixed group.

In addition, there were significant main effects of year for bedtime (P < 0.001), wake-up time (P < 0.001), sleep time on weekdays (P < 0.001), bedtime on weekends (P < 0.05), morningness score (P < 0.05), and daytime dozing (P < 0.05; ). Bedtimes on weekdays were later in the fourth and fifth years compared with the first and the second years (P < 0.01; and ). Wake-up time on weekdays was earlier in the first year than the other years (P < 0.01). Sleep time on weekdays was longer in the first to third years than in the fifth year (P < 0.01). The morningness score was lower in the first year than in the second year (P < 0.05). Dozing off was more frequent in the fourth year than the first year (P < 0.05; ).

Table 3 Parameters of the sleep/wake habit, subjective sleep estimation, and daytime symptoms for 5 years

Discussion

The present study surveyed the characteristics of awakening, sleep/wake habits, subjective sleep quality, and daytime symptoms in adolescents.

The reliabilityCitation8 and validityCitation10 of the ME questionnaire were confirmed. Construct validity was confirmed for the questionnaire items on sleep/wake habits, subjective sleep quality, and daytime symptoms.Citation7 To assess the reliability of the items, a 1-year test-retest method was utilized. Resulting reliability coefficients ranged from 0.43–0.50. These values reflect a moderate correlation and have an almost large effect size,Citation11 suggesting that this questionnaire has satisfactory reliability.

For any given year, 16%–26% (mean 19%) of the students reported that they habitually self-awakened that year. However, only one-quarter of these students (5% of all 362 students) consistently self-awakened for 5 consecutive years. In comparison, 10.3% of university students in a cross-sectional study who were several years older than the participants in the present study reported self-awakening.Citation6 Students with consistent habits of self-awakening at a predetermined time went to sleep earlier, got up earlier in the morning, slept for a longer time, and had higher ME scores than did students who did not habitually self-awaken. These results are consistent with previous surveys on self-awakening among university studentsCitation6 and adults.Citation3 These cross-sectional studies reported that people who self-awaken got up and went to bed earlier, had higher ME scores, and were more consistent in their nocturnal sleep time than those who did not habitually self-awaken.Citation3,Citation6 These results lead to the conclusion that individuals who consistently self-awake have a morningness chronotypology and regular sleep/wake schedules.

Studies that examined the effects of self-awakening at an unusual time found that it disturbed sleep,Citation12 for example, by extending sleep latencyCitation2 and increasing the number of awakenings.Citation1 However, Matsuura et alCitation6 found that self-awakening at a usual time did not harm sleep, but was associated with improved mood at awakening and less dozing off in the daytime. The results of the present study are consistent with Matsuura et al’s findings. Students who had the habit of self-awakening for 5 consecutive years felt better after awakening and dozed off less in the daytime compared with students who did not habitually self-awaken. Other studies have reported that self-awakening can prevent sleep inertia.Citation13,Citation14 Sleep inertia is the state of lowered arousal that occurs immediately after awakeningCitation15,Citation16 from normal nocturnal sleep.Citation17 Furthermore, it was previously found that self-awakening could reduce daytime sleepiness.Citation18 Therefore, except for the case of self-awakening at an unusual time, it is likely that self-awakening has positive effects on daily life, particularly with respect to alertness during the daytime.

Previous studies of the sleep/wake habits of self- awakening individuals were cross-sectional surveys using reports of only one time period. These studies reported that 52% of adultsCitation3 and 10.3% of university studentsCitation6 had habitual self-awakening habits. However, the habit of self-awakening is not always stable, so habitual self-awakening may occur less than the percentages reported in those studies. In the present study, 40% of all the students were mixed in their history of self-awakening; that is, they reported self-awakening in some years but not in others. Only 5% of the students consistently self-awakened over 5 years. These students went to bed and got up earlier than the mixed type with inconsistent habits of self-awakening. To clarify the characteristics of the sleep/wake habits of the consistent type for other age groups, a longitudinal study is required.

Bedtime and awakening time on weekdays were later, and sleep time for weekday evenings lengthened with the advancing years. These findings are consistent with those of other studies that found that bedtimes gradually became later during adolescence.Citation19 The data in the present study were gathered from 362 students who attended the same school for 5 consecutive years. Therefore, these changes may be due to developmental factors such as brain maturational changesCitation20 and/or social factors such as school schedules, but they are not likely to be explained by individual differences.

This study has several limitations. First, the small percentage (n = 17, 5%) of students who consistently self-awakened lowered the statistical power of the analysis. Further research with larger samples is needed. Second, because of the small number of female participants, gender differences could not be investigated. However, gender differences in sleep/wake habits among adolescents have been reported.Citation21 Further work is required to clarify gender differences in the habit of self-awakening. Third, the data of this study were based on self-reports, which could lead to bias. However, as seen above, the data is partially similar to a cross-sectional survey of self-awakening and sleep/wake habits.Citation6 In addition, the results of previous studies that experimentally compared self-awakening to forced-awakening were also similar to the results of the present survey; for example, self-awakening increases the number of awakenings from sleepCitation1 and comfortable awakening.Citation13 This suggests that self-report bias was minimized in this study. Finally, the participants were between 15–19 years old. However, people who never use an alarm for awakening could be significantly older.Citation3 Thus, age may influence habitual self-awakening and sleep/wake schedules. Consequently, further longitudinal research with a sample having a wider range of ages is needed.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BellCRAwakening from sleep at a pre-set timePercept Mot Skills1980502503508

- LaviePOksenbergAZomerJIt’s time, you must wake up nowPercept Mot Skills1979492447450229461

- MoorcroftWHKayserKHGriggsAJSubjective and objective confirmation of the ability to self-awaken at a self-predetermined time without using external meansSleep199720140459130333

- ZepelinHREM sleep and the timing of self-awakeningsBull Psychon Soc1986244254256

- ZungWWWilsonWPTime estimation during sleepBiol Psychiatry1971321591644326202

- MatsuuraNHayashiMHoriTComparison of sleep/wake habits of university students with or without a habit of self-awakeningPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200256322322412047567

- HoriTMiyashitaAShirakawaSIshiharaKFukudaKHayashiMSurvey on the developmental changes of sleep-wake habits and sleep problems from infants to advanced ages in Japanese populationAbstract of Research Project, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) funded by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, sports and Culture, Project No. 07301013 (in Japanese)1998

- IshiharaKMiyashitaAInugamiMFukudaKYamazakiKMiyataYThe results of investigation by the Japanese version of Morningness-Eveningness QuestionnaireShinrigaku Kenkyu19865728791 Japanese3784166

- HorneJAOstbergOA self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythmsInt J Chronobiol197642971101027738

- IshiharaKSaitohTInoueYMiyataYValidity of the Japanese version of the Morningness-Eveningness QuestionnairePercept Mot Skills1984593863866

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum1988

- HawkinsJSShawPSleep satisfaction and intentional self-awakening: an alternative protocol for self-report dataPercept Mot Skills1990702447450

- IkedaHHayashiMThe effect of self-awakening from nocturnal sleep on sleep inertiaBiol Psychol2010831151919800388

- KaidaKNittonoHHayashiMHoriTEffects of self-awakening on sleep structure of a daytime short nap and on subsequent arousal levelsPercept Mot Skills2003973 Pt 21073108415002849

- FerraraMDe GennaroLThe sleep inertia phenomenon during the sleep-wake transition: theoretical and operational issuesAviat Space Environ Med200071884384810954363

- TassiPMuzetASleep inertiaSleep Med Rev20004434135312531174

- IkedaHHayashiMEffect of sleep inertia on switch cost and arousal level immediately after awakening from normal nocturnal sleepSleep and Biological Rhythms200862120125

- IkedaHHayashiMEffect of self-awakening on daytime sleepinessPaper presented at: The Joint Congress of ASRS, JSSR, and JSCOctober 24–27, 2009Osaka, Japan

- YangCKKimJKPatelSRLeeJHAge-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagersPediatrics2005115Suppl 125025615866859

- CampbellIGHigginsLMTrinidadJMRichardsonPFeinbergIThe increase in longitudinally measured sleepiness across adolescence is related to the maturational decline in low-frequency EEG powerSleep200730121677168718246977

- GiannottiFCortesiFSebastianiTOttavianoSCircadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescenceJ Sleep Res200211319119912220314