Abstract

Objective

Patients with Parkinson’s disease frequently complain of sleep disturbances and loss of muscle atonia during rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep is not rare. The orexin-A (hypocretin-1) hypothalamic system plays a central role in controlling REM sleep. Loss of orexin neurons results in narcolepsy-cataplexy, a condition characterized by diurnal sleepiness and REM sleep without atonia. Alterations in the orexin-A system have been also documented in Parkinson’s disease, but whether these alterations have clinical consequences remains unknown.

Methods

Here, we measured orexin-A levels in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid from eight patients with Parkinson’s disease (four males and four females) who underwent ventriculography during deep brain-stimulation surgery and performed full-night polysomnography before surgery.

Results

Our results showed a positive correlation between orexin-A levels and REM sleep without muscle atonia.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that high levels of orexin-A in Parkinson’s disease may be associated with loss of REM muscle atonia.

Introduction

Sleep disorders and diurnal sleepiness are frequent in Parkinson’s disease.Citation1 Polysomnography studies have shown rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep dysregulation with REM sleep onset on diurnal napsCitation2,Citation3 and loss of muscle atonia,Citation4 which is defined as “excessive amount of sustained or intermittent elevation of submental electromyographic tone or excessive phasic submental or limb electromyographic twitching.”Citation4 Loss of REM atonia is a core phenomenon of REM sleep behavioral disorder (RBD),Citation5 a condition characterized by vigorous and injurious motor behaviors during REM sleep.Citation6

The orexin system plays a key role in REM sleep regulation. The loss of orexin neurons results in narcolepsy-cataplexy, a condition characterized by severe diurnal sleepiness, REM sleep onset during daytime naps, and cataplexies. REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) and RBD have also been reported to occur in narcolepsy.Citation7

Orexin neurotransmission has been shown to be altered in Parkinson’s disease (PD).Citation8–Citation10 However, polysomnographic data were not available in these postmortem studies. Furthermore, we showed that ventricular orexin levels were not correlated with mean sleep latency, suggesting that orexin deficit might not be involved in daytime sleepiness in PD.Citation11 Thus, the clinical expression of orexin deficit in PD remains unknown.Citation12

The objective of this study was to determine whether orexin-A levels in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from PD patients were correlated with REM sleep without atonia.

Patients and methods

Patients

Consecutive patients with idiopathic PDCitation13 who were scheduled for deep brain-stimulation neurosurgery were invited to participate in the study, irrespective of whether they had sleep complaints. We did not include patients taking medications known to affect sleep or REM atonia or patients with sleep apnea syndrome defined as an apnea/hypopnea index greater than ten per hour of sleep. Disease severity was assessed based on the motor subscore of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale III after overnight withdrawal of dopaminergic treatment. The study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to study inclusion.

Polysomnography

Sleep recordings were obtained during attended polysomnography 1 week before the scheduled date of neurosurgery. Polysomnography included electroencephalogram recordings (C4–A1, C3–A2, and O1–O2 leads), two electrooculograms, one submental electromyogram (EMG), and bilateral anterior tibialis EMGs. Also recorded were nasal pressure, oral airflow, thoracic and abdominal movements, and pulse oximetry. Video recordings were not obtained. Patients took their usual PD medications and were free to go to sleep when they wanted to.

Sleep stages were scored by two sleep specialists who had extensive experience with recordings in PD patients (AB and XD), according to the modified American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria,Citation14 with allowance for RSWA. RSWA was scored as previously described by Lapierre and Montplaisir.Citation16 Tonic chin-muscle activity during REM sleep was defined as chin EMG amplitude greater than twice the amplitude measured during a baseline EMG signal for atonia. Phasic EMG events were defined as any burst of activity lasting 0.3–5 seconds and having amplitude greater than four times the baseline EMG signal. Tonic and phasic EMG activities were scored from the submental EMG signal per 3-second mini-epochs of REM sleep containing or not containing “any” EMG activity (tonic, phasic, or a combination of both EMG activities).Citation17 We then reported loss of REM atonia as the percentage of REM sleep mini-epochs with “any” EMG activity. Tonic and phasic EMG increases associated with respiratory arousals were excluded from the analysis.

Collection of ventricular cerebrospinal fluid

Ventriculography performed to assist in the proper placement of an electrode in the subthalamic nucleus require the removal of CSF just before the injection of the contrast agent into the ventricle. In each of our patients, 3 mL of ventricular CSF was immediately frozen and stored at −80°C until use for the orexin-A assayCitation8

Orexin-A assay

Orexin-A (hypocretin-1) was measured in crude CSF using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, CA, USA). The detection limit was 50 pg/mL, and intra-assay variability was 5%. Each CSF sample was tested in duplicate.

Statistics

Correlations between orexin-A levels and sleep parameters were evaluated using Spearman’s rank-correlation test and the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patients

We studied eight consecutive patients – four males and four females – whose clinical features are reported in . In all eight patients, surgery was performed under regional anesthesia between 10 am and 12 am.

Table 1 Nighttime sleep parameters

No patients or bed partners reported violent movements during sleep, although the spouse of patient #7 reported limb and body jerking.

Correlation between orexin-A levels and nighttime sleep parameters

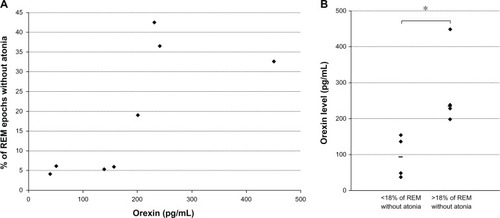

Orexin-A levels did not correlate with total sleep time (P = 0.23), REM duration (P = 0.45), or REM latency (P = 0.66). In contrast, orexin-A levels showed a significant positive correlation with the percentage of REM epochs without atonia, ie, percentage of 3-second mini-epochs classified as “any” (ρ = 0.83, P = 0.027) ().

Figure 1 (A) Association between ventricular orexin-A levels (pg/mL) and loss of rapid-eye-movement (REM) atonia. (B) Orexin-A levels (pg/mL) based on the percentage of REM without atonia.

As previously describedCitation6,Citation17 RSWA is considered clinically significant when any submental EMG activity was present for more than 18% of the total REM sleep duration. According to this criterion, four of our patients had RSWA (#2, #3, #4, and #7). These four patients had higher median (interquartile range) orexin-A levels than the four patients with REM sleep atonia (235 pg/mL [215–345] vs 94 pg/mL [44–147]; Mann–Whitney test P = 0.036, ). No other sleep parameters differed significantly between these two groups of patients.

Discussion

Our results show a significant relationship between ventricular CSF orexin-A levels and REM sleep characteristics in patients with PD. Despite the small number of patients, we found a correlation between orexin-A levels and RSWA. Our results suggest that orexin-A signaling may be associated with loss of muscle atonia during REM sleep in patients with PD.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of potential correlations between ventricular CSF orexin-A levels and polysomnographic data in patients with PD. We undertook this study to investigate the physiological significance of altered orexin neurotransmission in PD, which has generated controversy.Citation12 The strength of our study is the use of ventricular CSF. A previous study in PD patients found that ventricular CSF orexin levels correlated with the number of orexinergic neurons.Citation9 Furthermore, while a lumbar CSF study failed to report a significant correlation between orexin levels and disease severity in a large group of 62 PD patients,Citation18 a significant correlation was reported with ventricular samples.Citation8

The main limitations of our study are the small number of patients and the absence of control subjects. We excluded patients taking sleep-altering medications and EMG activities concurrent with respiratory arousals,Citation19 which may have further limited bias in our study.

In our study, PD patients with higher ventricular CSF orexin levels exhibited larger numbers of RSWA epochs than did patients with lower orexin levels, suggesting that preserved orexin drive may be involved in loss of REM atonia. These results are congruent with experiments demonstrating that orexin neurons are strongly involved in muscle-tone control. Orexin neurons exert a facilitating influence on muscle tone, both directly via their projections on trigeminal motor neuronsCitation20 and spinal motor neuronsCitation21 and indirectly via the locus coeruleus neurons.Citation22 Orexin injections into the locus coeruleus increase muscle toneCitation23 and interrupt pedunculopontine nucleus-induced muscle atonia.Citation24 However, regulation of muscle atonia relies on complex relationships and interactions between the orexin system, the locus coeruleus (in which orexin facilitates muscle activity), and the pontine inhibitory area (in which orexin inhibits muscle activity).

Our results contrast with those obtained in narcolepsy-cataplexy, in which orexin levels negatively correlated with RSWA.Citation25 However, narcolepsy-cataplexy and PD are two different diseases, and the process leading to orexinergic neuron loss is likely different. Orexin neurons are the primary target of an acute and specific neuronal aggression in narcolepsy, leading to a 90% reduction in the orexin neuron pool.Citation26 In contrast, PD is a chronic, slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease, affecting primarily dopaminergic neurons, with a process not fully understood, leading to partial (23%–60%) orexin neuron loss.Citation10 As an illustration, no cataplexy has been reported in PD patients, even in patients with undetectable orexin levels.Citation8,Citation12

Our results are also in contrast with a recent study that found similar orexin lumbar levels in five RBD patients.Citation27 However, these patients had idiopathic RBD and no sign of PD.

Conclusion

The loss of REM atonia in patients with higher orexin levels illustrates the complexity of the symptoms induced by altered orexin neurotransmission in PD.Citation28 Experimental trials of orexin antagonists could be of interest in the transgenic mouse model of RSWA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Garcia-BorregueroDLarrosaOBravoMParkinson’s disease and sleepSleep Med Rev20037211512912628213

- ArnulfIKonofalEMerino-AndreuMParkinson’s disease and sleepiness: an integral part of PDNeurology20025871019102411940685

- BaumannCFerini-StrambiLWaldvogelDWerthEBassettiCLParkinsonism with excessive daytime sleepiness – a narcolepsy-like disorder?J Neurol2005252213914515729517

- IranzoASantamaríaJRyeDBCharacteristics of idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder and that associated with MSA and PDNeurology200565224725216043794

- American Academy of Sleep MedicineThe International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual2nd edDarien (IL)American Academy of Sleep Medicine2005

- GagnonJFBédardMAFantiniMLREM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in Parkinson’s diseaseNeurology200259458558912196654

- DauvilliersYArnulfIMignotENarcolepsy with cataplexyLancet2007369956049951117292770

- DrouotXMoutereauSNguyenJPLow levels of ventricular CSF orexin/hypocretin in advanced PDNeurology200361454054312939433

- FronczekROvereemSLeeSYHypocretin (orexin) loss in Parkinson’s diseaseBrain2007130Pt 61577158517470494

- ThannickalTCLaiYYSiegelJMHypocretin (orexin) cell loss in Parkinson’s diseaseBrain2007130Pt 61586159517491094

- DrouotXMoutereauSLefaucheurJPLow level of ventricular CSF orexin-A is not associated with objective sleepiness in PDSleep Med201112993693721978722

- BaumannCRScammellTEBassettiCLParkinson’s disease, sleepiness and hypocretin/orexinBrain2008131Pt 3e9117898005

- HughesAJDanielSEKilfordLLeesAJAccuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 casesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19925531811841564476

- SilberMHAncoli-IsraelSBonnetMHThe visual scoring of sleep in adultsJ Clin Sleep Med20073212113117557422

- ConsensFBChervinRDKoeppeRAValidation of a polysomnographic score for REM sleep behavior disorderSleep200528899399716218083

- LapierreOMontplaisirJPolysomnographic features of REM sleep behavior disorder: development of a scoring methodNeurology1992427137113741620348

- FrauscherBIranzoAGaigCNormative EMG values during REM sleep for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorderSleep201235683584722654203

- YasuiKInoueYKanbayashiTNomuraTKusumiMNakashimaKCSF orexin levels of Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degenerationJ Neurol Sci20062501–212012317005202

- IranzoASantamariaJSevere obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea mimicking REM sleep behavior disorderSleep200528220320616171244

- PeeverJHLaiYYSiegelJMExcitatory effects of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) in the trigeminal motor nucleus are reversed by NMDA antagonismJ Neurophysiol20038952591260012611960

- YamuyJFungSJXiMChaseMHHypocretinergic control of spinal cord motoneuronsJ Neurosci200424235336534515190106

- MileykovskiyBYKiyashchenkoLISiegelJMMuscle tone facilitation and inhibition after orexin-a (hypocretin-1) microinjections into the medial medullaJ Neurophysiol20028752480248911976385

- KiyashchenkoLIMileykovskiyBYLaiYYSiegelJMIncreased and decreased muscle tone with orexin (hypocretin) microinjections in the locus coeruleus and pontine inhibitory areaJ Neurophysiol20018552008201611353017

- TakakusakiKTakahashiKSaitohKOrexinergic projections to the cat midbrain mediate alternation of emotional behavioral states from locomotion to cataplexyJ Physiol2005568Pt 31003102016123113

- KnudsenSGammeltoftSJennumPJRapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder in patients with narcolepsy is associated with hypocretin-1 deficiencyBrain2010133Pt 256857920129934

- ThannickalTCMooreRYNienhuisRReduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsyNeuron200027346947411055430

- AndersonKNVincentASmithIEShneersonJMCerebrospinal fluid hypocretin levels are normal in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorderEur J Neurol20101781105110720113337

- FronczekRBaumannCRLammersGJBassettiCLOvereemSHypocretin/orexin disturbances in neurological disordersSleep Med Rev200913192218819824