Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age characterized by chronic anovulation and polycystic ovary morphology and/or hyperandrogenism. Management of clinical manifestations of PCOS, such as menstrual irregularities and hyperandrogenism symptoms, includes lifestyle changes and combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs). CHCs contain estrogen that exerts antiandrogenic properties by triggering the hepatic synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin that reduces the free testosterone levels. Moreover, the progestogen present in CHCs and in progestogen-only contraceptives suppresses luteinizing hormone secretion. In addition, some types of progestogens directly antagonize the effects of androgens on their receptor and also reduce the activity of the 5α reductase enzyme. However, PCOS is related to clinical and metabolic comorbidities that may limit the prescription of CHCs. Clinicians should be aware of risk factors, such as age, smoking, obesity, diabetes, systemic arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, and a personal or family history, of a venous thromboembolic event or thrombophilia. This article reports a narrative review of the available evidence of the safety of hormonal contraceptives in women with PCOS. Considerations are made for the possible impact of hormonal contraceptives on endocrine, metabolic, and cardiovascular health.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a heterogeneous endocrine disorder with prevalence rates ranging from 5% to 13.9% in women of reproductive age.Citation1,Citation2 PCOS is mainly characterized by chronic anovulation, polycystic ovary morphology, and hyperandrogenism. However, there is considerable interindividual variation in the presentation of diverse clinical and metabolic symptoms that vary across ethnic groups and geographic regions.Citation1,Citation3

Together with lifestyle changes, combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) are the first-line management options for clinical manifestations of PCOS, specifically menstrual irregularity, hirsutism, and acne.Citation4–Citation7 CHCs contain an estrogen component (ethynylestradiol [EE], estradiol valerate, or estradiol) and a progestogen component that vary in terms of composition and affinity to receptors of other steroid hormones (mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, androgens, and estrogen). Both estrogen and progestogen contribute to management of the clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism.Citation8,Citation9

PCOS are associated with clinical and metabolic comorbidities that may limit the prescription of CHCs in women with PCOS. Common risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as systemic arterial hypertension (SAH), obesity, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome (MeTS), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), can develop in women with PCOS by the fourth decade of life.Citation5,Citation10–Citation12 According to the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use of the World Health Organization (WHO), some of these comorbidities (MeTS, SAH, DM2 with vasculopathy, and dyslipidemia plus another risk factors) are considered to be category 3 (a condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method) or 4 (a condition which represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used) (). In both categories, progestogen-only contraceptives (POCs) are typically considered a safer option for women presenting with risk factors for CVD.Citation13 In cases of presenting with contraindications to CHC, POCs or nonhormonal contraceptivesCitation13 can be coadministered with antiandrogen medication to control hyperandrogenism symptoms.Citation14

Table 1 Eligibility criteria of the World Health Organization

Because of the paucity of data about the impact of CHCs on cardiovascular and metabolic parameters in PCOS patients, most recommendations are based on studies involving ovulatory women. The objective of this narrative review is to present an evaluation of the evidence on available hormonal contraceptives, their noncontraceptive benefits, and adverse effects in women with PCOS, according to the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use of the WHO.Citation13 A specific focus of this review is considerations for endocrine, metabolic, and cardiovascular health of women with PCOS.

Review criteria

The PubMed electronic bibliographic database was searched from January 1960 to September 2015 to identify reviews, clinical guidelines, observational, and interventional studies evaluating the effects of the use of any hormonal contraception in women or with or without diagnosed PCOS. Only published full-text articles in English were included. We prioritized the results of meta-analyses and guidelines/consensus.

The following search strategy was used: ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (lipid metabolism)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (carbohydrate metabolism OR insulin)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (systemic arterial hypertension)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (obesity)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (thrombophilia)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (mellitus diabetes type 2)), ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (dyslipidemia)), and ((polycystic ovary syndrome) AND (hormonal contraceptive) AND (metabolic syndrome)). The narrative synthesis of identified data was conducted. First, the benefits of CHCs on hyperandrogenism symptoms and endometrial cancer in women with PCOS are considered. Next, the six most important negative effects of hormonal contraceptives are considered in the context of their use in women with PCOS.

Noncontraceptive benefits of hormonal contraception in women with PCOS

Management of hyperandrogenism symptoms

Hyperandrogenism is the most prominent diagnostic component of PCOS.Citation3 Decrease in clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism is considered not only to have esthetical benefits but also to contribute to a reduction of risk factors for metabolic disorders.Citation4

Evidence suggests that CHCs decrease hyperandrogenism symptoms by reducing production of androgens. More specifically, the estrogen component of CHCs has been shown to increase the hepatic synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), subsequently reducing the free testosterone that can bind the androgen receptor.Citation15 This antiandrogen effect is more prominent with the use of EE than with the use of natural estrogen.Citation15 A systematic review of 42 experimental studies with meta-analysis demonstrated that independent of the type of progestogens present in combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing 20–35 µg EE, the use of COCs was associated with a 61% reduction of free testosterone levels. However, COCs containing low doses (20 µg) of EE or consisting of second-generation progestogens (levonorgestrel) had a smaller effect on the increase of SHBG compared to COCs containing higher EE doses or other progestogens (50% vs 150%–250% increase SHBG).Citation16

In addition to these antiandrogen properties, progestogen promotes negative feedback on the surge of luteinizing hormone, as a result reducing the ovarian androgen production. Some progestogens can directly antagonize the effects of androgens on the androgen receptor and also reduce the activity of the 5α reductase enzyme, which converts testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the latter being a highly potent androgen.Citation9 COCs containing cyproterone acetate have been shown to have a higher antiandrogen activity than desogestrel and drospirenone in long-term users (12 months or more), but not in short-/medium-term users (up to 6 months).Citation17

Based on this evidence, the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology have recommended the use of COCs as the initial pharmacological treatment of choice for women with PCOS, but the guidelines do not suggest any specific combination of compounds.Citation5 The European Society of Endocrinology specifically recommends COCs containing cyproterone acetate for a more effective management of hyperandrogenism.Citation18 However, in the presence of estrogen contraindication, drugs with an antiandrogen effect should be used in combination with effective contraceptives (nonhormonal methods or POCs).Citation18 Similarly, the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society has established a protocol for the treatment of hirsutism in which the COCs of choice are those containing progestogens with a greater antiandrogen potential, such as cyproterone, chlormadinone, and drospirenone.

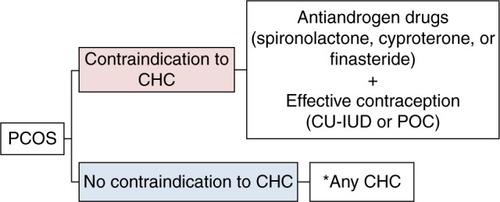

Nonoral methods containing EE have not been discussed in these clinical guidelines, possibly due to scarcity of evidence. However, these contraceptive methods can be expected to exert antiandrogen properties by reducing free testosterone and increasing SHBG. Since some POCs have the ability to inhibit luteinizing hormone secretion, POCs may also have some effect on the improvement of hyperandrogenism. In ovulatory women, the etonogestrel implant was shown to be associated with a reduction of testosterone and SHBG after 12 weeks of use.Citation19 The effect of POCs in women with PCOS, however, still requires investigation. Based on the existing clinical guidelines, a possible flow diagram of eligibility of hormonal contraceptives for women with PCOS is presented in .

Figure 1 Flowchart for contraceptive choice for PCOS women.

*Note: Any CHC, although preference should be given to those containing ethinylestradiol.

Endometrial cancer

A systematic review with meta-analysis of eleven case– control studies concluded that compared to women without PCOS, women with PCOS are at three times higher risk for endometrial cancer (odds ratio [OR] 2.79, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.31–5.95) at any age, but not for ovarian or breast cancer.Citation20 While this estimate might have been overstated as a result of inclusion of studies that used self-reported diagnosis of PCOS and with possible selection biases related to failure to control for body mass index (BMI), overall PCOS presents a prominent risk factor for endometrial cancer.Citation20 General population data show that hormonal contraceptive users have a lower incidence of endometrial cancer than nonusers.Citation21,Citation22 A prospective observational study is needed to confirm this effect of hormonal contraceptives in women with PCOS.

Choices and challenges

Systemic arterial hypertension

SAH can be found in women with PCOS,Citation10 especially as one of the diagnostic criteria for MeTS.Citation23 However, comorbidities detected in PCOS, such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, can justify SAH independently of PCOS itself.Citation8 In an attempt to exclude these possible confounding factors, Chen et alCitation24 demonstrated a positive correlation of total testosterone levels and free androgen index with blood pressure. High blood pressure levels were also identified in the parents of women with PCOS compared to the parents of healthy women matched for age and BMI.Citation25

Endogenous estradiol can result in the vasodilation of blood vesselsCitation26 by increasing the production of nitric oxide and appropriate collagen synthesis, thus reducing arterial pressure.Citation27 In turn, endogenous progesterone supports this hypotensive action by having an antimineralocorticoid effect.Citation28 However, EE that is present in most of CHCs, due to its greater potency compared to estradiol, elevates the production of the hepatic angiotensinogen, which causes an elevation of blood pressure via the rennin–angiotensin– aldosterone system, regardless of the route of administration.Citation26 Despite the development of new progestogens, only drospirenone has the antimineralocorticoid activity of endogenous progesterone, regardless of the EE dose present in COCs.Citation29–Citation31

As a result, systolic arterial hypertension is regarded an adverse effect of COCs.Citation32 Several studies have shown an association between hypertension and the use of COCs with a high EE dose, although an increased blood pressure was observed even with the use of monophasic pills containing 30 µg EE.Citation33 In a cohort study, an increased relative risk of 1.8 (95% CI=1.5–2.3) to develop systolic arterial hypertension was observed in COC users compared to nonusers.Citation34 In addition, higher diastolic arterial pressure levels and a poorer pressure control have been reported in hypertensive women using COCs compared to hypertensive nonusers, regardless of age, body weight, or hypertensive drugs used.Citation35 A reduction in pressure levels of hypertensive women was detected ~6 months after the interruption of COC use.Citation36

The negative effect of EE appears to be independent of the route of administration of CHCs since the hepatic activation promoted by EE occurs independently of the route of CHC administration.Citation37 Within this context, POCs have the advantage of having no negative effect on blood pressure, thus representing a safe contraceptive method in women with PCOS.Citation13

In conclusion, according to the eligibility criteria of the WHO, the use of CHCs is not indicated for women with hypertension with or without PCOS, regardless of the route of administration or estrogen type. If a woman with PCOS presents associated SAH, the eligible treatment methods are POCs or nonhormonal contraceptives. However, in women with severe SAH (≥160×100 mmHg) or with associated vasculopathy, the depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) is category 3 and the CHCs are category 4 ().Citation13

Table 2 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with SAH

Lipid metabolism

Dyslipidemia is associated with PCOS independently of weight.Citation38 Of the variables associated with lipid profile, CHCs have a greater negative impact on triglyceride (TG) levels, causing more than 40% of an increase in TG levels in women without PCOSCitation39,Citation40 and of up to 75% in women with PCOS,Citation37,Citation41 regardless of the route of EE administration. In addition, women with PCOS who do not use CHCs may also show a reduction of high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, whereas increases in total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels are less frequent.Citation42

In general, EE administered by any route increases very low density lipoprotein-cholesterol and TG levels.Citation40 Progestogens play a significant modulatory role in the elevation of TG and HDL-cholesterol levels promoted by estrogens.Citation43 In contrast, the administration of POCs does not seem to interfere with the lipid profile.Citation44 However, DMPA is associated with increased low density lipoprotein and reduced HDL levels, although this negative effect is transitory and does not persist 2 years after the discontinuation of this method.Citation45

A meta-analysis has demonstrated that the use of COCs for at least 3 months was significantly associated with an increase in HDL and TG levels in women with PCOS, although these changes were not clinically significant.Citation46 To the best of our knowledge, there is no information of the effect of POCs on the lipid profile of women with PCOS.

The 2009 Medical Eligibility Criteria of the WHO considered the use of combined contraceptive methods for women with hypertriglyceridemia as category 3 due to the increased risk of CVD and pancreatitis. However, a recent systematic review with meta-analysis, based on limited data from poor-quality observational studies, has demonstrated that women with known dyslipidemia using CHCs may be at increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and may experience a minimal increase in risk for arterial or venous thrombosis but the use of CHC was not associated with a high risk of pancreatitis.Citation47 Based on this evidence, according to the 2015 version of the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, women in reproductive age with known dyslipidemias without other known cardiovascular risk factors can generally use any hormonal contraceptive method.Citation13 In the presence of one of these risk factors, all CHCs should be avoided. DMPA has been classified as the category 3 due its negative effect on HDL levels in women with dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk factors ().Citation13

Table 3 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with dyslipidemia

Carbohydrate metabolism and insulin sensitivity

PCOS is a risk factor for DM2.Citation48 Approximately 30% of women with PCOS have reduced glucose tolerance and ~10% of them have DM2. For comparison, prevalence rates of reduced glucose tolerance and undiagnosed DM2 in healthy women aged 20–44 years are 7.8% and 1%, respectively.Citation48

Insulin resistance seems to play an important role in the physiopathology of PCOS.Citation49 The first studies that evaluated the effect of COCs on glucose metabolism in healthy women showed a negative effect on glucose tolerance. However, these studies were conducted in the 1960s; at this time, high-dose COCs were used (EE doses of 50 µg or higher).Citation50,Citation51 A comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies has shown that the use of COCs for at least 3 months was not associated with negative effects on glucose metabolism as measured by the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, fasting glucose to insulin ratios, and homeostatic model assessments.Citation46

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 trials on the participation of CHCs in carbohydrate metabolism in women without DM2 has demonstrated that independent of the route of administration and estrogen type (EE or natural), CHCs have a limited effect on carbohydrate metabolism, and therefore no adverse effects for endocrine health. The authors, however, were unable to draw strong recommendations based on this evidence as the majority of studies compared different types of contraceptives, had small sample sizes, high lost-to-follow-up rates, poorly described methodologies, and failed to control for BMI.Citation52

In a systematic review with meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials comparing COCs with metformin in PCOS, metformin was found to be superior in terms of reduction of fasting insulin, albeit the two treatments showed no significant difference in fasting glucose levels or the onset of DM2. To establish the safest option in terms of metabolic outcome of hormonal contraceptives, trials evaluating the long-term effects of these medications are needed.Citation53

In summary, evidence suggests that women with PCOS should use CHCs containing low EE doses (<50 µg) as these do not affect carbohydrate metabolism or pose a risk of developing DM2. According to the Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use of the WHO, CHCs can still be used by patients with associated PCOS and diabetes, regardless of insulin use. However, POCs or nonhormonal contraceptives should be used in the presence of associated vasculopathy (or diabetes of >20 years’ duration), except DMPA since this compound is associated with the reduction of HDL levels ().Citation13

Table 4 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with diabetes mellitus (DM) associated or not with vasculopathy

Body weight

Many clinicians and users have observed weight gain during the use of hormonal contraception, with a consequent early discontinuation of the method despite its efficacy or delay in its prescription.Citation54–Citation56 Several mechanisms have been proposed to the mechanisms underlying this observed impact of hormonal contraceptives on weight gain, but none of them has been fully confirmed.Citation57

Specific research evidence on the association between CHCs and body weight in women with PCOS appears to be lacking entirely, but many studies have investigated effects of different hormonal contraceptives on body weight in healthy women. In a retrospective study on 2,138 women uninterruptedly using DMPA, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), or the copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD), 1 year follow-up all groups showed an increase in body weight, compared to baseline, with a mean weight gain of 1.3, 0.7, and 0.2 kg in the DMPA, LNG-IUS, and Cu-IUD groups, respectively (P<0.0001). After 10 years of use, the mean weight had risen by 6.6, 4.0, and 4.9 kg among the DMPA, LNG-IUS, and Cu-IUD users, respectively. DMPA users had gained more weight than the LNG-IUS (P=0.0197) and Cu-IUD users (P=0.0294). The authors concluded that users of hormonal and nonhormonal contraceptive methods gained a significant amount of weight over the years, but DMPA users gained more weight over a treatment period of up to 10 years than women using either the LNG-IUS or Cu-IUD.Citation58

A Cochrane review evaluated the relationship between various forms of POCs and their association with weight gain,Citation59 albeit the presence of PCOS was not considered in the review. The authors have identified two studies that investigated weight gain in DMPA users compared to Cu-IUD users: while one study showed no significant difference, the other showed a statistically significant weight gain in the DMPA group at 1 year (mean difference [MD] =2.28 kg; 95% CI 1.79–2.77), 2 years (MD =2.71 kg; 95% CI 2.12–3.30), and 3 years (MD =3.17 kg; 95% CI 2.51–3.83), with this difference being significant only for patients with normal weight or overweight. Regarding body composition, the meta-analysis included two studies showing that DMPA users had a greater increase in body fat (%) (MD 11.00; 95% CI 2.64–19.36) and a greater decrease in lean body mass (%) (MD −4.00; 95% CI −6.93 to −1.07) compared to users of other hormonal methods. Another study, included in the meta-analysis, demonstrated that the LNG-IUS group showed an increase in body fat mass (2.5% vs −1.3%, respectively; P=0.029) and a reduction of percent change in lean body mass (−1.4% vs 1.0%, respectively; P=0.027) in relation to Cu-IUD users, although no significant change in body weight was observed between groups. Despite these considerations, the authors concluded that there is limited evidence of weight gain when using POCs. Except for DPMA, mean gain was <2 kg up to 12 months for most studies, but the weight change of the POC group generally did not differ significantly from groups using another contraceptives.Citation59

A group of Danish authors recently carried out two randomized controlled trials which demonstrated that the use of metformin alone or in combination with COCs was associated with weight loss and improved body composition compared with the use of COCs alone.Citation60,Citation61 One of these studies revealed a small but significant weight gain in the group taking COCs alone, leading the authors to a conclusion that metformin use with or without COCs should be considered as an alternative for the treatment of PCOS to avoid weight gain with COCs alone.Citation61

Overall, the authors of a systematic review with meta-analysis of as many as 49 trials on the link between combination contraceptives and weight change in healthy women were unable to confidently determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight.Citation54 They have suggested a need for trials with a placebo or nonhormonal group to control for other factors, including changes in weight over time.Citation54

The WHO, however, considers any hormonal contraceptive method to be adequate for obese women who have no other associated risk factors for CVD.Citation13 Due to the absence of evidence in women with PCOS, data for the general population have been applied to draw recommendations to women with PCOSCitation62 ().

Table 5 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in obese women without any other cardiovascular risk factors

Metabolic syndrome

PCOS is commonly associated with MeTS, which is diagnosed by the presence of at least three of the following criteria: waist circumference ≥88 cm, fasting glycemia ≥100 mg/dL, TGs ≥150 mg/dL, HDL <50 mg/dL, and blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg.Citation23 Prevalence rates of MeTS in women with PCOS vary according to the region under study. For example, prevalence rates in the US range from 43% to 46%.Citation63,Citation64 To compare, three to six times lower prevalence rates were reported in Italy (5%–17.3%)Citation65 and even four to 20 times lower prevalence rates were reported for women in People’s Republic of China (2.3%–12.2%).Citation66 In Brazil, prevalence rates of MeTS range from 33.3% to 45.4%, depending on the PCOS phenotype.Citation67 The observed differences are likely to be related to factors inherent to a specific population under the study. Especially regarding PCOS phenotypes, diagnostic criteria, diet, and lifestyle may interfere with the prevalence of this syndrome. Overall, regardless of the diagnostic criterion of PCOS, the prevalence of MeTS in women with PCOS is at least twice as high as the prevalence population without PCOS.Citation68

MeTS is associated with an increased risk of arterial thrombosis events since it was linked to the development of atherosclerosis. In addition, it has been reported that MeTS is associated with a twofold increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).Citation23

The presence of MeTS in the general population is associated with a twofold increase in the risk of developing CVD.Citation23 Since women with PCOS are at an increased risk of MetS and cardiovascular events,Citation69 a hormonal contraceptive method should be chosen with caution in women with PCOS associated with MeTS. According to the WHO, only POCs (except for DMPA) and nonhormonal contraceptives are suitable for women with MeTS that carries multiple risk factors for CVD. The DMPA has unfavorable metabolic effects, such as a reduction of HDL levels, which limit its use in situations of an increased cardiovascular risk ().Citation13

Table 6 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with MeTS

Arterial and venous thrombosis

CVDs include MI, angina, cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), and peripheral vascular disease (ie, peripheral arterial disease, venous thrombosis, and deep vein thrombosis). In women with PCOS, those who were taking COCs had a twofold increased risk of VTE (characterized by deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) and those not taking oral contraceptives had a 1.5-fold increased risk.Citation70

A systematic review of observational studies demonstrated that women with PCOS have a twofold increased risk of CVD than the population without PCOS (relative risk 2.02; 95% CI 1.47–2.76), a risk that remained ~1.5 times higher after adjusting for BMI (relative risk 1.55; 95% CI 1.27–1.89).Citation71 In a systematic review and a meta-analysis of five studies, the risk of nonfatal stroke was twofold higher among climacteric women with a history of PCOS compared to the population without PCOS (OR 1.94; 95% CI 1.19–3.17). However, there was no significant difference for MI and/or mortality due to CVD.Citation72

A recent Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis, inclusive of nonrandomized trials, showed that the risk of MI or CVA was only increased in women using COCs containing ≥50 µg of estrogen, with the prescription of COCs with <50 µg of estrogen showing to be safe regarding the risk of MI (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–1.0) or CVA (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.9–1.1).Citation73

A Danish historical cohort study included 1,626,158 women aged 15–49 years without a history of CVD or cancer. The authors concluded that the absolute risks of CVA and MI associated with the use of COCs were low. This risk was increased by a factor of 0.9–1.7 with COCs that included EE at a dose of 20 µg and by a factor of 1.3–2.3 with those that included EE at a dose of 30–40 µg, with no differences in risk according to progestin type.Citation74

Regarding VTE, a Danish historical cohort study conducted on 8,010,290 women aged 15–49 years without a history of thrombotic disease demonstrated that, compared to nonusers of CHCs, the relative risk of confirmed VTE in users of COCs containing 30–40 µg EE varied according to the type of progestogen present. After adjusting for time of use, the rate of confirmed VTE was 2.2 (1.7–3.0) for users of COCs with desogestrel, 2.1 (1.6–2.8) for users of COCs with gestodene, and 2.1 (1.6–2.8) for users of COCs with drospirenone compared to users of COCs with levonorgestrel. The risk of confirmed VTE was not increased with the use of POCs. The authors concluded that users of COCs with desogestrel, gestodene, or drospirenone were at least at twice the risk of VTE compared with users of COCs with levonorgestrel.Citation75 However, this result was not confirmed in a prospective, controlled, noninterventional cohort study conducted in the US and in six European countries. In this study, the use of COCs containing drospirenone was associated with similar risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism compared to COCs without drospirenone or COCs containing levonorgestrel.Citation76

Another Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that all COCs were associated with an increased risk of VTE, but the size of the effect depended both on the progestogen used and the dose of EE.Citation77 The authors have estimated that the relative risk of VTE for COCs with 30–35 µg ethinylestradiol and gestodene, desogestrel, cyproterone acetate, or drospirenone was similar and ~50%–80% higher than for COCs with levonorgestrel. On this basis, the COCs with lower dose of EE with levonorgestrel would be safer in order to reduce the risk of VTE.Citation77 However, this result should be considered with caution since the review was inclusive of both chronic users (several years) of COCs containing levonorgestrel and recent users of COCs containing other progestogens. This is an important limitation because the first year of CHC use involves a higher risk of VTE.Citation75–Citation77 Despite the difference in thrombogenic potential according to the antiandrogen effect of progestogens, the absolute risk for VTE is small among healthy women in reproductive age.

Another historical Danish cohort study assessed the risk of VTE in 1,626,158 users of nonoral products compared to the standard reference COC with levonorgestrel and 30–40 µg estrogen or nonusers aged 15–49 years. The authors concluded that users of transdermal patches or vaginal rings have a 7.9 and 6.5 times increased risk of VTE compared with nonusers of CHC of the same age.Citation74 In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and case– control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies, the relative risk of VTE was 0.90 (95% CI: 0.57–1.45) for POC users, 0.61 (95% CI: 0.24–1.53) for LNG-IUS users, and 2.67 (95% CI: 1.29–5.53) for DMPA users, compared to nonusers. The authors concluded that the use of POC was not associated with an increased risk of VTE compared with nonusers of hormonal contraception and that the relationship between DMPA and VTE needs to be further investigated.Citation78

Although it is safe to prescribe any hormonal contraceptive to obese women with no other associated risk factors, obesity alone can involve approximately a 24-fold increase in the risk of VTE among COC users compared to nonusers of COCs with a BMI <25 kg/m2.Citation79 For this reason, although obesity is not a contraindication for CHC use, caution should be taken in the association of CHC use and obesity.

It is important to point out that screening for thrombophilia before prescribing a hormonal contraceptive is not recommended.Citation80 presents the WHO’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use in women with arterial and venous thrombosis.Citation13 The main clinical conditions related to prescription of hormonal contraceptives in women with PCOS are summarized in .

Table 7 Medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with a history of arterial or venous thrombosis

Table 8 Summary of medical eligibility criteria for hormonal contraceptive use in women with comorbidities related to polycystic ovary syndrome

Conclusion

CHCs are the first-choice treatment options for PCOS. This review suggests one of the important reasons for their use is evident reduction of hyperandrogenism symptoms and endometrial cancer risk. However, metabolic disorders may be aggravated or even triggered by the use of some CHCs.

Many clinical guideline recommendations for hormonal contraceptive use in women with PCOS are based on studies in women without PCOS. Consequently, clinicians should still evaluate each patient individually and consider the presence of risk factors, such as age, smoking, obesity, diabetes, SAH, dyslipidemia, and a personal or family history of a venous thromboembolic events or thrombophilia. summarizes the recommendation of hormonal contraceptive use in the presence of comorbidities. When the use of estrogen is contraindicated for the patient or when multiple risk factors for CVD are present or intolerance of EE occurs, the use of POCs or nonhormonal contraceptives is recommended. If these methods do not adequately control the symptoms of hyperandrogenism, an alternative is to combine a POC or a nonhormonal method with an antiandrogen medication, such as spironolactone, cyproterone, or finasteride.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NormanRJDewaillyDLegroRSHickeyTEPolycystic ovary syndromeLancet2007370958868569717720020

- MeloASVieiraCSBarbieriMAHigh prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in women born small for gestational ageHum Reprod20102582124213120573680

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM—Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop GroupRevised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)Hum Reprod2004191414714688154

- VrbikovaJCibulaDCombined oral contraceptives in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod Update200511327729115790599

- FauserBCTarlatzisBCRebarRWConsensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop GroupFertil Steril20129712838.e2522153789

- GoodmanNFCobinRHFutterweitWGlueckJSLegroRSCarminaEAmerican Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology, and Androgen Excess and PCOS Society disease state clinical review: guide to the best practices in the evaluation and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome – part 1Endocr Pract201521111291130026509855

- YildizBOApproach to the patient: contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2015100379480225701301

- EhrmannDAPolycystic ovary syndromeN Engl J Med2005352121223123615788499

- NaderSDiamanti-KandarakisEPolycystic ovary syndrome, oral contraceptives and metabolic issues: new perspectives and a unifying hypothesisHum Reprod200722231732217099212

- EltingMWKorsenTJBezemerPDSchoemakerJPrevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac complaints in a follow-up study of a Dutch PCOS populationHum Reprod200116355656011228228

- AzzizRWoodsKSReynaRKeyTJKnochenhauerESYildizBOThe prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected populationJ Clin Endocrinol Metabol200489627452749

- MoranLJMissoMLWildRANormanRJImpaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod Update201016434736320159883

- World Health OrganizationMedical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use5th edGenevaWorld Health Organization2015 Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/MEC-5/en/

- Escobar-MorrealeHFCarminaEDewaillyDEpidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome SocietyHum Reprod Update201218214617022064667

- CharitidouCFarmakiotisDZournatziVThe administration of estrogens, combined with anti-androgens, has beneficial effects on the hormonal features and asymmetric dimethyl-arginine levels, in women with the polycystic ovary syndromeAtherosclerosis2008196295896517418849

- ZimmermanYEijkemansMJCoelingh BenninkHJBlankensteinMAFauserBCThe effect of combined oral contraception on testosterone levels in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod Update20142017610524082040

- BhattacharyaSMJhaAComparative study of the therapeutic effects of oral contraceptive pills containing desogestrel, cyproterone acetate, and drospirenone in patients with polycystic ovary syndromeFertil Steril20129841053105922795636

- ConwayGDewaillyDDiamanti-KandarakisEESE PCOS Special Interest GroupThe polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement from the European Society of EndocrinologyEur J Endocrinol20141714P12924849517

- Merki-FeldGSImthurnBRosselliMSpanausKImplanon use lowers plasma concentrations of high-molecular-weight adiponectinFertil Steril2011951232720576266

- BarryJAAziziaMMHardimanPJRisk of endometrial, ovarian and breast cancer in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod Update201420574875824688118

- CibulaDGompelAMueckAOHormonal contraception and risk of cancerHum Reprod Update201016663165020543200

- BahamondesLBahamondesVMShulmanLPNon-contraceptive benefits of hormonal and intrauterine reversible contraceptive methodsHum Reprod Update201521564065126037216

- GrundySMCleemanJIDanielsSRDiagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific StatementCirculation2005112172735275216157765

- ChenMJYangWSYangJHRelationship between androgen levels and blood pressure in young women with polycystic ovary syndromeHypertension20074961442144717389259

- YilmazMBukanNErsoyRChenCLHoHNYangYSGlucose intolerance, insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors in first degree relatives of women with polycystic ovary syndromeHum Reprod20052092414242015890734

- OelkersWKEffects of estrogens and progestogens on the renin-aldosterone system and blood pressureSteroids19966141661718732994

- ChenWSrinivasanSRLiSBoerwinkleEBerensonGSGender-specific influence of NO synthase gene on blood pressure since childhood: the Bogalusa Heart StudyHypertension200444566867315466663

- OelkersWDrospirenone, a progestogen with antimineralocorticoid properties: a short reviewMol Cell Endocrinol20042171–225526115134826

- Sitruk-WareRNew progestagens for contraceptive useHum Reprod Update200612216917816291771

- PalaciosSFoidartJMGenazzaniARAdvances in hormone replacement therapy with drospirenone, a unique progestogen with aldosterone receptor antagonismMaturitas200655429730716949774

- de NadaiMNNobreFFerrianiRAVieiraCSEffects of two contraceptives containing drospirenone on blood pressure in normotensive women: a randomized-controlled trialBlood Press Monit201520631031526154851

- CurtisKMMohllajeeAPMartinsSLPetersonHBCombined oral contraceptive use among women with hypertension: a systematic reviewContraception200673217918816413848

- WilsonESCruickshankJMcMasterMWeirRJA prospective controlled study of the effect on blood pressure of contraceptive preparations containing different types and dosages of progestogenBr J Obstet Gynaecol19849112125412606440589

- Chasan-TaberLWillettWCMansonJEProspective study of oral contraceptives and hypertension among women in the United StatesCirculation19969434834898759093

- LubiancaJNFaccinCSFuchsFDOral contraceptives: a risk factor for uncontrolled blood pressure among hypertensive womenContraception2003671192412521653

- LubiancaJNMoreiraLBGusMFuchsFDStopping oral contraceptives: an effective blood pressure-lowering intervention in women with hypertensionJ Hum Hypertens200519645145515759027

- BattagliaCManciniFFabbriRPolycystic ovary syndrome and cardiovascular risk in young patients treated with drospirenone-ethinylestradiol or contraceptive vaginal ring. A prospective, randomized, pilot studyFertil Steril20109441417142519591981

- MastorakosGKoliopoulosCCreatsasGAndrogen and lipid profiles in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome who were treated with two forms of combined oral contraceptivesFertil Steril200277591992712009344

- GuazzelliCABarreirosFABarbosaRTorloniMRBarbieriMExtended regimens of the contraceptive vaginal ring versus hormonal oral contraceptives: effects on lipid metabolismContraception201285438939322067754

- Morin-PapunenLMartikainenHMcCarthyMIComparison of metabolic and inflammatory outcomes in women who used oral contraceptives and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in a general populationAm J Obstet Gynecol20081995529.e11018533124

- VieiraCSMartinsWPFernandesJBThe effects of 2 mg chlormadinone acetate/30 mcg ethinylestradiol, alone or combined with spironolactone, on cardiovascular risk markers in women with polycystic ovary syndromeContraception201286326827522464410

- BerneisKRizzoMLazzariniVFruzzettiFCarminaEAtherogenic lipoprotein phenotype and low-density lipoproteins size and subclasses in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200792118618917062762

- GodslandIFBiology: risk factor modification by OCs and HRT lipids and lipoproteinsMaturitas200447429930315063483

- BarkfeldtJVirkkunenADiebenTThe effects of two progestogen-only pills containing either desogestrel (75 microg/day) or levonorgestrel (30 microg/day) on lipid metabolismContraception200164529529911777489

- BerensonABRahmanMWilkinsonGEffect of injectable and oral contraceptives on serum lipidsObstet Gynecol2009114478679419888036

- HalperinIJKumarSSStroupDFLaredoSEThe association between the combined oral contraceptive pill and insulin resistance, dysglycemia and dyslipidemia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studiesHum Reprod201126119120121059754

- DragomanMCurtisKMGaffieldMECombined hormonal contraceptive use among women with known dyslipidemias: a systematic review of critical safety outcomesContraception Epub2015810

- SilvaRCPardiniDPKaterCEPolycystic ovary syndrome, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular risk and the role of insulin sensitizing agentsArq Bras Endocrinol Metabol200650228129016767294

- MeloASDiasSVCavalli RdeCPathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome: multifactorial assessment from the foetal stage to menopauseReproduction20151501R112425835506

- PhillipsNDuffyTOne-hour glucose tolerance in relation to the use of contraceptive drugsAm J Obstet Gynecol19731161911004697175

- KalkhoffRKEffects of oral contraceptive agents on carbohydrate metabolismJ Steroid Biochem1975669499561100908

- LopezLMGrimesDASchulzKFSteroidal contraceptives: effect on carbohydrate metabolism in women without diabetes mellitusCochrane Database Syst Rev20144CD006133

- CostelloMFShresthaBEdenJMetformin versus oral contraceptive pill in polycystic ovary syndrome: a Cochrane reviewHum Reprod20072251200120917261574

- GalloMFLopezLMGrimesDACarayonFSchulzKFHelmerhorstFMCombination contraceptives: effects on weightCochrane Database Syst Rev20141CD003987

- VrbikovaJHainerVObesity and polycystic ovary syndromeObes Facts200921263520054201

- MoreauCClelandKTrussellJContraceptive discontinuation attributed to method dissatisfaction in the United StatesContraception200776426727217900435

- KarlssonRLindénAvon SchoultzBSuppression of 24-hour cholecystokinin secretion by oral contraceptivesAm J Obstet Gynecol1992167158591442956

- ModestoWde Nazaré Silva dos SantosPCorreiaVMBorgesLBahamondesLWeight variation in users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a copper intrauterine device for up to ten years of useEur J Contracept Reprod Health Care2015201576325160484

- LopezLMEdelmanAChenMOtternessCTrussellJHelmerhorstFMProgestin-only contraceptives: effects on weightCochrane Database Syst Rev20137CD008815

- GlintborgDAltinokMLMummHHermannAPRavnPAndersenMBody composition is improved during 12 months’ treatment with metformin alone or combined with oral contraceptives compared with treatment with oral contraceptives in polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20149972584259124742124

- GlintborgDMummHAltinokMLRichelsenBBruunJMAndersenMAdiponectin, interleukin-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and regional fat mass during 12-month randomized treatment with metformin and/or oral contraceptives in polycystic ovary syndromeJ Endocrinol Invest201437875776424906976

- DomecqJPPrutskyGMullanRJAdverse effects of the common treatments for polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201398124646465424092830

- GlueckCJPapannaRWangPGoldenbergNSieve-SmithLIncidence and treatment of metabolic syndrome in newly referred women with confirmed polycystic ovarian syndromeMetabolism200352790891512870169

- ApridonidzeTEssahPAIuornoMJNestlerJEPrevalence and characteristics of metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndromeJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20059041929193515623819

- CarminaENapoliNLongoRARiniGBLoboRAMetabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): lower prevalence in southern Italy than in the USA and the influence of criteria for the diagnosis of PCOSEur J Endocrinol2006154114114516382003

- GuoMChenZJMacklonNSCardiovascular and metabolic characteristics of infertile Chinese women with PCOS diagnosed according to the Rotterdam consensus criteriaReprod Biomed Online201021457258020800551

- MeloASVieiraCSRomanoLGFerrianiRANavarroPAThe frequency of metabolic syndrome is higher among PCOS Brazilian women with menstrual irregularity plus hyperandrogenismReprod Sci201118121230123622096008

- YildizBOBozdagGYapiciZEsinlerIYaraliHPrevalence, phenotype and cardiometabolic risk of polycystic ovary syndrome under different diagnostic criteriaHum Reprod201227103067307322777527

- WiltgenDSpritzerPMVariation in metabolic and cardiovascular risk in women with different polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypesFertil Steril20109462493249620338557

- BirdSTHartzemaAGBrophyJMEtminanMDelaneyJARisk of venous thromboembolism in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based matched cohort analysisCMAJ20131852E115E12023209115

- de GrootPCDekkersOMRomijnJADiebenSWHelmerhorstFMPCOS, coronary heart disease, stroke and the influence of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysisHum Reprod Update201117449550021335359

- AndersonSABarryJAHardimanPJRisk of coronary heart disease and risk of stroke in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Cardiol2014176248648725096551

- RoachREHelmerhorstFMLijferingWMStijnenTAlgraADekkersOMCombined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic strokeCochrane Database Syst Rev20158CD011054

- LidegaardØLøkkegaardEJensenASkovlundCWKeidingNThrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraceptionN Engl J Med2012366242257226622693997

- LidegaardØNielsenLHSkovlundCWSkjeldestadFELøkkegaardERisk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001-9BMJ2011343d642322027398

- DingerJBardenheuerKHeinemannKCardiovascular and general safety of a 24-day regimen of drospirenone-containing combined oral contraceptives: final results from the International Active Surveillance Study of Women Taking Oral ContraceptivesContraception201489425326324576793

- de BastosMStegemanBHRosendaalFRCombined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosisCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD010813

- ManthaSKarpRRaghavanVTerrinNBauerKAZwickerJIAssessing the risk of venous thromboembolic events in women taking progestin-only contraception: a meta-analysisBMJ2012345e494422872710

- PompERle CessieSRosendaalFRDoggenCJRisk of venous thrombosis: obesity and its joint effect with oral contraceptive use and prothrombotic mutationsBr J Haematol2007139228929617897305

- WuORobertsonLTwaddleSScreening for thrombophilia in high-risk situations: systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. The Thrombosis: Risk and Economic Assessment of Thrombophilia Screening (TREATS) studyHealth Technol Assess200610111110