Abstract

Globally, unintended adolescent pregnancies pose a significant burden. One of the most important tools that can help prevent unintended pregnancy is the timely use of emergency contraception (EC), which in turn will decrease the need for abortions and complications related to adolescent pregnancies. Indications for the use of EC include unprotected sexual intercourse, contraceptive failure, or sexual assault. Use of EC is recommended within 120 hours, though is most effective if used as soon as possible after unprotected sex. To use EC, adolescents need to be equipped with knowledge about the various EC methods, and how and where EC can be accessed. Great variability in the knowledge and use of EC around the world exists, which is a major barrier to its use. The aims of this paper were to 1) provide a brief overview of EC, 2) discuss key social determinants affecting knowledge and use of EC, and 3) explore best practices for overcoming the barriers of lack of knowledge, use, and access of EC.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Background

Despite significant declines in adolescent pregnancy in the past two decades, it continues as a significant burden globally, with approximately 16 million (11%) of all births worldwide to young women 15–19 years.Citation1 Most of these pregnancies are unintended, and 95% occur in low- and middle-income countries.Citation1 Global rates of unintended adolescent pregnancies vary widely. A recent review article showed that among the 21 countries with complete statistics, the pregnancy rate among 15- to 19-year-olds was highest in the US (57 pregnancies per 1,000 females) and lowest in Switzerland (eight pregnancies per 1,000 females).Citation2 In those countries with incomplete statistics, higher rates were reported in some former Soviet countries and highest rates in Mexico and sub-Saharan African countries.Citation2 The proportion of teen pregnancies that ended in abortion ranged from 17% in Slovakia to 69% in Sweden.Citation2 Among 15- to 19-year-olds globally, complications secondary to pregnancy, childbirth, and unsafe abortions are the second-leading cause of mortality.Citation1 Adolescent pregnancies are also associated with an array of negative social and economic consequences, compromising adolescents’ future educational and economic opportunities.Citation3

Although there are several causes for unintended pregnancies, one of the most important tools that can help in preventing them is the timely use of emergency contraception (EC). EC can help prevent the need for abortions and prevent maternal and infant complications by offering a second chance to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse, contraceptive failure, or sexual assault. Due to the fact that no contraceptive has 100% efficacy, adolescents need access to EC as a backup method.

To use EC, adolescents need to be equipped with knowledge about the various methods and how they can have access to them. Great variability in the knowledge and use of EC exists around the world, though the US and European countries have high EC awareness.Citation4,Citation5 In 80% of the 45 countries studied, <3% of sexually active women aged 14–49 years had ever used EC.Citation4 A 2010 policy report found that awareness of EC ranged from 6% among married women in Indonesia to a high of 35% among married women in Ghana; however, <3% of women reported that they actually used EC.Citation5 Additionally, availability and cost of EC varies around the world.Citation5 A study by the American Society for Emergency Contraception showed that even though levonorgestrel (LNG) methods of EC have been made available over the counter, many of them are being sold behind the counter or are locked up, due to high cost of the product (US$48 on average).Citation6

The objectives of this paper are to provide a brief overview of EC, discuss key social determinants affecting knowledge and use of EC, and explore best practices for overcoming barriers to lack of knowledge and use of EC.

Brief overview of EC

Brief history of EC

The roots of modern EC date back to the 1920s, when high doses of ovarian estrogen extracts were found to interfere with pregnancy in mammals. Veterinarians were the first to apply this method to prevent unwanted pregnancies in horses and dogs. Evidence remained scattered until the 1960s, when physicians in the Netherlands administered high-dose estrogen to a 13-year-old girl who was a rape victim. In the 1970s, the Yuzpe regimen was introduced, which consisted of a combined-hormone regimen (100 μg ethinyl estradiol and 1 mg norgestrel, given as two doses 12 hours apart) that replaced the high-dose-estrogen EC methods. The Yuzpe regimen replaced high-dose estrogen chiefly because it resulted in a lower incidence of side effects. At the same time, research on regimens omitting estrogen began, predominantly in Latin America. The Yuzpe regimen, though very popular until the beginning of the twenty-first century, has been surpassed by LNG EC products, due to LNG’s higher efficacy and fewer side effects. Around the same time, the copper intrauterine device (IUD) was introduced as the only nonhormonal method of EC. Ulipristal acetate (UPA), a selective progesterone-receptor modulator, was approved as EC in the UK in 2009 and in 2010 in the US.

Various methods of EC (from most effective to least effective)

Both hormonal and non-hormonal methods of EC exist.

Nonhormonal EC

The copper IUD is the only nonhormonal method and the most effective EC method. The usual protocol is to insert it within 5 days of unprotected sex or contraceptive failure or up to 5 days after ovulation. Studies have shown that IUDs can be inserted as EC after 5 daysCitation7 and anytime in the cycle if a highly sensitive pregnancy test is negative.Citation8,Citation9 The primary mechanism of the copper IUD is an inhibitory effect of copper ions on sperm that prevents fertilization. The copper IUD also adversely affects endometrial receptivity. An advantage of the copper IUD is that it can be left in utero after its use as EC, serving as highly effective, long-acting reversible contraception for 10–12 years. Few contraindications for the copper IUD as an EC method exist. Specific contraindications are current pregnancy, current pelvic inflammatory disease, allergy to copper, and uterine anomalies. Risks of expulsion, infection, and/or perforation are low with the copper IUD.Citation10

Hormonal methods

Ulipristal acetate

This is the most effective and newest form of EC pill. It is currently available in 79 countries,Citation11 and is given as 30 mg in a single dose orally. It is a selective progesterone-receptor modulator.Citation12 One study reported that UPA delays ovulation.Citation12 A 2010 meta-analysis of studies reported that for those women treated with UPA within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, the risk of pregnancy was almost half that of those receiving LNG, and if given within 24 hours, the risk of pregnancy was reduced by two-thirds in those receiving UPA compared to LNG.Citation13 There are no medical contraindications for the use of UPA other than pregnancy. It is effective for up to 5 days after contraceptive failure, and efficacy does not decline over the 5-day period.Citation13

Mifepristone

This is an antiprogesterone agent that is effective for EC. However, mifepristone is not available in many countries, and has been mainly used in the People’s Republic of China as EC. The oral dose is 10 or 50 mg, and is effective up to 5 days after contraceptive failure. Efficacy does not decline over time.Citation14 It acts by preventing or delaying ovulation in a dose-dependent fashion.Citation14 It is not commonly used, due to cost and accessibility. Access to mifepristone is highly regulated in the US.

Levonorgestrel

This is the most widely available form of EC worldwide, and is available over the counter in several countries. LNG as EC is a 1.5 mg dose, given as soon as possible after contraceptive failure or unprotected sex. Although it is effective for up to 5 days (120 hours) after contraceptive failure, its efficacy declines over time. It works by preventing or delaying ovulation, and works only up to the luteinizing hormone surge.Citation14

Yuzpe regimen

This consists of 100 μg ethinyl estradiol and 1 mg norgestrel, given as two doses 12 hours apart. It is effective for up to 5 days, but efficacy declines over time. It works by preventing or delaying ovulation. It has the lowest efficacy of all the EC methods.Citation11

Contraindications for oral EC

The most common contraindications for oral EC are ongoing pregnancy (not because of teratogenicity, but simply because if one is pregnant, there is no need for these medications), hypersensitivity to any product component, and undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Weight and efficacy

The efficacy of all oral EC is decreased in obese women, although obesity is not a contraindication for EC. One study reported that the failure rate of LNG (5.8%) was greater than that for UPA (2.6%) in obese women.Citation15 For women with a body mass index (BMI) of 26 or over who used progestin-only EC, pregnancy rates were no different than would be expected if they had not used EC at all. UPA appeared to lose effectiveness at a BMI threshold of 35.Citation15,Citation16 In contrast, the efficacy of the copper IUD as EC is unaffected by weight. For women who have a BMI of 26 or greater, if the copper IUD is unavailable for EC, UPA should be considered as the second-best available option over LNG.Citation15

Key social determinants affecting knowledge and use of EC

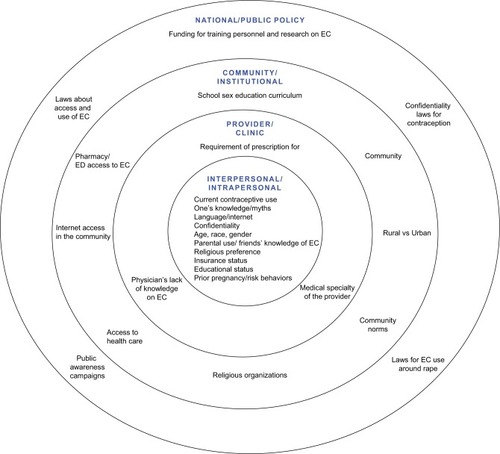

We propose an evidence-based ecological model (), accounting for proximal and distal factors at the levels of national/public policy, community/institutional, provider/clinic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal factors. While an ecological model most comprehensively illustrates the complexity of adolescent knowledge and use of EC, limitations exist. The chosen categories do not necessarily represent all possible factors, and there may be overlap both within and among different categories. Proximal factors may receive more attention than warranted, because they are more easily detected. Both causal and noncausal predisposing factors may not be clearly delineated. Nevertheless, an ecological model enables us to address multiple layers of causal and predisposing risk, while adapting to EC knowledge and use.

Figure 1 A socioecological model looking at the factors influencing knowledge and use of emergency contraception (EC)

Intrapersonal-level factors

Studies have shown that older teens are more likely to have an awareness of EC. One of the reasons could be that older teens are likely to be more sexually active than younger teens.Citation17,Citation18 Sex differences in knowledge have been found in the US and other countries. In a 2015 study, young women (86%) reported higher rates of “hearing about emergency contraception” than young men (70%).Citation18 Another study of 278 Turkish male university students showed that only 14.5% had heard about EC.Citation19 EC awareness was measured among 11,392 women aged 15–44 years using data from the 2003 CA Health Interview Survey.Citation20 They found that awareness was lower among teens, women of color, poor women, those with publicly funded insurance, those without a usual source of care, immigrants, non-English-speaking, and rural residents.Citation20 Lack of insurance is a major barrier in receiving preventive reproductive care in a timely manner, and thus uninsured adolescents are at greater risk of pregnancy.Citation21,Citation22 One study of homeless, uninsured, and/or high-risk adolescents reported high rates of EC-pill awareness (70%–86%), but significant gaps in knowledge of mechanism, access, and proper use of EC pills.Citation18 One study showed that adolescents generally lacked sufficient knowledge about what EC is and its mechanism of action.Citation17

Minority urban adolescents had several misconceptions about EC pills, as well as concerns about confidentiality, and were highly influenced by opinions of family and friends close to them.Citation23 Another study showed that familiarity with EC, having a new sex partner, having unprotected sex at least once, having negative feelings toward pregnancy, and using condoms as one’s main contraceptive method, were all positively associated with likelihood of recent EC use.Citation24 Language barriers can decrease use of EC. In a study in California, where researchers posed as English versus Spanish callers called a pharmacy to obtain EC, Spanish callers were less successful in obtaining EC.Citation25 In a Nicaraguan study, women who used EC were younger, had lower parity and had higher education and socioeconomic status than those who were not using EC.Citation26 In a cross-sectional study at Rhode Island, women who used EC were more likely to have a higher educational status, be single, have had unprotected last intercourse, and less likely to have had a sexually transmitted infection (STI).Citation27

Research shows increased likelihood of EC use in adolescents with school and/or home access to the internet. These adolescents are likely to use the internet to access information about EC and a location from which to obtain EC.Citation28 In a randomized controlled trial, access to computer assisted provision of EC in waiting rooms in urgent care clinics increased knowledge of EC in a state where EC had been available without a prescription for 3 years.Citation29 In a Finnish study, smoking, dating, poor school achievement, and not living in a nuclear family, were all associated with increased EC use.Citation30

Interpersonal-level factors

A 2016 cross-sectional study of students 15–19 years old in Brazil showed that knowledge of EC was not associated with its use, but knowing someone that had used the method increased its use.Citation31 It was also found that peer-group conversations on EC had greater influence on the use of EC than knowledge itself, economic status, or sexual experience.Citation31 Adolescents with higher levels of parental monitoring had lower rates of EC use.Citation32

Provider/clinic-level factors

A 1999 study found that only 17% of pediatricians routinely counseled about EC.Citation33 Female pediatricians were more likely to do so, but 73% of respondents could not identify any of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved methods of EC.Citation33 A 2016 study showed that the type of specialty of the provider and the proportion of women of reproductive age in the practice were related to knowledge and provision of some forms of EC. Among the reproductive health specialists, 81% provided LNG EC in their practice, although only half (52%) had heard of UPA and very few had provided it (14%). The more effective methods of EC, such as UPA and the copper IUD, were little known and had rarely been provided outside reproductive health specialties.Citation34 In one study, women preferred to talk with their physicians and get a prescription for EC compared to nonprescription access to EC.Citation32

Community/institutional-level factors

One study showed that adolescents who lived in rural areas, had transportation issues, or lacked access to pharmacies had lower levels of EC use.Citation18 A 2009 study of inner-city adolescents in New York City found low levels of EC knowledge: only 30% of the sexually experienced adolescents had heard of EC.Citation35 Nevertheless, once they found out about it, the vast majority (87%) professed an intent to try the method if the need arose.Citation35 Community access to family-planning clinics increased odds of using EC.Citation36

National/public policy-level factors

Encompassing all these determinants for adolescent knowledge and use of EC are policies that national groups and governments have put in place to improve access to EC in adolescents. Even with these policies, many adolescents are still not aware of or lack knowledge about the proper use of EC. EC awareness increased after a public-awareness campaign in Scotland.Citation37 Princeton University has hosted a website dedicated to EC since 1996. The Emergency Contraception website is operated by the Office of Population Research at Princeton University and by the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals (http://ec.princeton.edu).

Adolescent use of EC significantly increased in the US from 8% in 2002 to 22% in 2011–2013.Citation38 A study from British Columbia showed cost savings with increased availability of EC as a nonprescription medication.Citation39 In April 2013, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step for use, without a patient needing a prescription and without age restrictions. UPA (Ella) can be purchased through online websites (eg, www.ella-kwikmed.com, www.prjktruby.com), which provide a medical prescription and deliver the medication. An increase in the cost of over-the-counter LNG EC in the US from about $25 to about $45 and lack of health insurance in many patients made it difficult for patients to buy these products.Citation40 Under the US’s 2010 Affordable Care Act, most insurers must cover all FDA-approved birth control for women, including over-the-counter contraceptive medications, such as EC. Similar legislation in other countries can improve access to and knowledge of EC.Citation40

Best practices for overcoming barriers to knowledge about and use of EC

In order to making a significant impact and improve knowledge and use of EC, there need to be comprehensive adolescent-focused programs that will 1) help assess knowledge of EC at the individual level, 2) improve use by making it readily available in a confidential manner, 3) increase over-the-counter and pharmacy access, 4) implement educational programs at the community or school level, and 5) have national policies that will reduce cost and improve access and availability of EC products readily for all adolescents. Programs should involve all relevant stakeholders, and have broad aims to influence social and cultural norms and laws and policies that affect the adolescent’s right to accurate knowledge on sexual and reproductive health.

Principles of intervention

Intervention should necessitate multisector involvement: this means simultaneously involving all stake holders in program planning, implementation, and outcome evaluations.Citation41 Stakeholders range from individuals to global organizations, and include adolescents and young adults, parents, extended family, siblings, teachers, school administrators, health care providers, clinic nurses and staff, staff of hospitals, community outreach programs, social workers, local community leaders, religious institutions, politicians and policy makers, and international organizations like the United Nations, the United States Agency for International Development, and the World Health Organization. Intervention needs to occur early in adolescence to promote healthy behavior patterns.Citation41 Both adolescent risk and protective factors should be targeted. Risk and protective factors develop during varying stages of adolescence. While some of these are problem-specific, many are general factors that predict multiple outcomes, such as adolescent pregnancy, substance abuse, poor school performance, violence, crime, and mental illness. Given the commonality of these risk factors across adolescent-behavior issues, targeting one risk factor will impact multiple problems.

Proposed interventions to improve knowledge of EC

In the following sections, we present interventions at the provider/clinic level, community level, and national/public policy level to help improve knowledge and use of EC, based on the ecological model in the Supplementary materials. Intervention at any of these levels in the model will have an impact on the other levels, especially at the individual level.

Provider/clinic-level interventions

Goals are to assess knowledge, provide confidential youth-friendly clinic services, and improve the delivery of EC.

Potential strategies to assess knowledge of EC

Providers and clinics can use self-administered, anonymous surveys (example in ) in order to assess knowledge of ECs and understand major misconceptions. Surveys are easy and convenient for both patients and providers. Analysis of the survey results can help providers determine the gaps and address them in an effective and efficient manner.

Table 1 Survey

Potential strategies to dispel any myths or misinformation about EC

Survey patients about their knowledge and review the answers. Ask patients what do they know about EC, why would they not want to use it, and/or why might they want to use it.

Potential strategies to improve access to and delivery of EC to adolescents

One of the most important interventions would be to discuss EC with any adolescent who comes in for an annual preventive care visit and/or a reproductive health care visit. This helps set the stage for when and if the need arises. The following represent various types of models of delivery of health care to adolescents.

Specialized adolescent clinics

These clinics are usually affiliated with a hospital and/or university. These also serve as referral centers for nearby health facilities and provide academic and research training for physicians. They can serve as the patient-centered medical home (PCMH),Citation42 and according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the PCMH model is a way to ensure continuity of care from birth to young adulthood and to provide coordinated health care among specialist and related service providers.Citation43 There are seven identified characteristics of the PCMH model: care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective.Citation43 While increasing care coordination and enhancing overall quality, this model also simultaneously reduces costs. Key to PCMH success are health information technology, such as the use of electronic medical records, and payment reform as outlined by the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Access to a PCMH can help providers deliver high-quality medical care, including contraception counseling, and provide EC to help prevent unintended pregnancies.

Community-based health care facilities

These facilities can be either a stand-alone or government-run institution, and can be an integral part of a district or a county health system. They can be focused family-planning clinics, such as Planned Parenthood, or a general practice.Citation44,Citation45 They can also serve as PCMHs for care of adolescents.

School-based or college-based health services

These clinics are linked with schools or colleges, and provide health services for those who study or live close to the schools and colleges.Citation46 School-based health centers (SBHCs) serve an essential role in providing access to high-quality, comprehensive care to underserved adolescents in many schools across the US.Citation47 They can be an efficient and important delivery medium for information on EC. The American Academy of Pediatrics recognizes the proven benefits and exciting potential of SBHCs. Traditional SBHCs are located in urban areas and schools with large student populations. In order to reach rural areas and schools with lower numbers of students, telehealth SBHCs (tSBHCs) are now being utilized. These tSBHCs provide sexual and reproductive services through telemedicine, and operate in communities where geographic barriers and financial challenges have prevented the establishment of SBHCs. tSBHCs are an important part of the PCMH model to help improve access to and use of EC.

Community-based centers

Some community centers provide health services in addition to educational and recreational services. These centers can be the starting point for health care for adolescents; they often have links with health facilities nearby, where adolescents and young people can be referred.Citation44,Citation48

Pharmacies

Most pharmacies around the world sell contraceptive products, such as condoms and EC, and some also provide clinic services.

Outreach programs, such as mobile clinics

Mobile health clinics have been able to provide comprehensive health services, including contraceptive services, by leveraging their mobility to treat people in the convenience of their own communities. They are particularly able to serve at-risk marginalized populations who have trouble navigating the health care system, who lack health insurance, or who live in rural environments with poor health care access.Citation49–Citation51 “Teen health vans” park in the heart of the community in familiar spaces, like shopping centers, recreation centers, or at or near schools, which lends themselves to the local community atmosphere. Of note, mobile clinics successfully attract young men, who tend to have poorer health-seeking behavior,Citation41 thus helping providers educate young males regarding safe sexual practices, use of condoms, and prevention of unintended pregnancies.

Potential strategies to provide confidential, youth-friendly clinic services

Research has shown that the main reasons for health services not reaching adolescents are lack of availability of youth-friendly services, complicated by cultural, access, and cost issues.Citation52 Access to health care services is an important component for prevention of teenage pregnancies. Research in the last two decades, conducted in both developed and developing countries, has focused on the barriers that adolescents face in accessing health services.Citation52 This research has pointed out clearly that youth need services that are sensitive to their unique developmental stage. As per Pathfinder International: “Health services are understood to be youth friendly if they have policies and attributes that attract youth to the facility or program, provide a comfortable and appropriate setting for youth, meet the needs of young people, and are able to retain their youth clientele for follow-up and repeat visits”.Citation53 Barriers to youth-friendly services to deliver EC or any form of contraception relate to restrictive policies, access, cost of care, and acceptability issues.Citation52 Lack of confidentiality and fear of parents finding out or parents’ reaction(s) are very significant barriers in developing countries. In order to overcome these barriers, principles derived from the World Health Organization Quality Assessment GuidebookCitation54 (Supplementary materials) must be incorporated into the services, which are as follows:

equitable – all adolescents, not just certain groups, are able to obtain the health services

accessible – adolescents are able to obtain the services that are provided

acceptable – services are provided to meet the expectations of adolescent clients

appropriate – the health services that adolescents need are provided

effective – services are provided in the right way, and make a positive contribution to the health of adolescents.

These interventions can be incorporated in the various types of clinic services described earlier. Relevant technologies, including websites, social media, and mobile phones, should be utilized to help with implementation of programs, customized to the area being targeted.

Community/school-level interventions

Reproductive and sexual health-education programs at schools can play an important role in educating adolescents about different types of contraception, including EC. It is the basic right of each adolescent to know about EC, in addition to comprehensive sex education that teaches them about bodily functions, puberty, sex, reproduction, safe sex, and contraceptive practices. If the adolescents are not informed of these, they will likely make poor choices about their sexual health and put themselves at risk for early and unintended pregnancies and STIs. Therefore, a comprehensive, medically accurate, age-appropriate curriculum should be developed to educate adolescents regarding their sexual and reproductive health. These curricula can be incorporated into schools at a state and national level. Adolescents must be educated on basic structure and function of the reproductive system, puberty, the menstrual cycle, menstrual hygiene, sex and safe-sex practices, contraception including EC, sexually transmitted diseases, nutrition, protection from sexual abuse and rape, and the availability of youth-friendly services. A review of 83 sexuality-education programs, 18 of them in developing countries, showed that sex-education programs can significantly (by two-thirds) reduce risky sexual behavior in young people.Citation55 A review in sub-Saharan Africa showed that school-based sex-education programs do make a significant improvement in the knowledge, intentions, and attitudes of adolescents.Citation56 Similar programs in Thailand improved knowledge, and adolescents were more likely to intend to refuse sex and decrease frequency of sex, although there was no change in condom use.Citation57 One review highlighted 17 characteristics for the effectiveness of such programs, which are related to program development, content, and implementation.Citation58 These can be incorporated to improve adolescent knowledge of EC ().

Table 2 Characteristics of effective sex-education programs

National-level interventions

Public service announcements/campaigns

In the US in 2011, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy joined the Ad Council (a collaboration of major advertising firms) to debut a groundbreaking, first-ever national multimedia public service campaign designed to reduce the rates of unplanned pregnancies. The campaign directed adolescents and young adults to bedsider.org, a comprehensive, online, youth-friendly program on contraceptive methods, which became a national success. This program is still recommended to adolescents and young adults to learn about contraception.

Television shows

TV shows can be a very effective method to reach large audiences about contraception. One such example is comedian Aziz Ansari’s popular show called Master of None on Netflix, where “plan B” makes for great comedy in his opening episode. Another example is the show East Los High on the Hulu network, which is popular among youth and Latinos. One episode included a youth who needed EC, and the episode stealthily incorporated EC-education points in its programming.

Legislation

Policies that will enable the following will increase awareness and use of EC:

making sure that ECs are available over the counter to any age and sex

protect adolescents’ rights to confidential reproductive health care services that will allow access to EC

ensure that EC is covered by insurance.

One such example would be California’s Family PACT (Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment) program. It is an innovative method of providing free, comprehensive, and confidential family-planning services to low-income adolescent and adult females and males.

Evaluation of interventions

Outcomes and relevant indicators to be evaluated

All of the interventions and their components listed can be considered for evaluation, including feasibility and cultural sensitivity, focusing on increase in knowledge and use of EC.

Method of evaluation

Pre- and postintervention studies using specific indicators can be performed. provides a comprehensive list of indicators that can potentially be utilized for these kinds of studies. Other methods, such as focus groups and in-depth interviews, can also be performed. Randomized controlled trials using external evaluators would be the best method, which should be incorporated if financial resources are available.

Table 3 Indicators for pre- and postintervention studies

Conclusion

Young people are the inheritors of our future. Young people are not the sources of problems – they are the resources that are needed to solve them. They are not expenses, but rather investments: not just young people, but citizens of the world, present as well as the future.Citation59

Adolescents have the right to lead healthy lives. They can do so when they are informed and given access to confidential and safe family-planning services, including information about EC, even before they become sexually active. This will help them lead healthier lives, prevent unintended pregnancies, and in turn will help them lead more productive lives. This will ultimately help the enhancement of a country’s economy, reduce poverty, and increase educational attainment.

Supplementary materials

Proposed interventions to improve knowledge and use of emergency contraception

Provider/clinic level

Assess knowledge of emergency contraception (EC) by using use self-administered, anonymous surveys

Dispel any myths or misinformation about EC by interviewing patients

Improve access and delivery of EC to adolescents:

following are various types of models for health care delivery to adolescents:

a. specialized adolescent clinics

b. community-based health care facilities

c. school-based or college-based health services

d. community-based centers

e. pharmacies

f. outreach programs, such as mobile clinics

Provide confidential, youth-friendly clinic services

Community/school level

Reproductive and sexual health-education programs at schools.

National/public policy level

Public service announcements/campaigns

Television shows

Legislation

World Health Organization framework for youth-friendly health services

An equitable point of delivery is one in which:

Policies and procedures are in place that do not restrict the provision of health services on any terms, and that address issues that might hinder the equitable provision and experience of care

Health care providers and support staff treat all their patients with equal care and respect, regardless of status

An accessible point of delivery is one in which:

Policies and procedures are in place that ensure health services are either free or affordable to all young people

The point of delivery has convenient working hours and convenient location

Young people are well informed about the range of health services available, and how to obtain them

Community members understand the benefits that young people will gain by obtaining health services, and support their provision

Outreach workers, selected community members, and young people themselves are involved in connecting health services with young people in the community

An acceptable point of delivery is one in which:

Policies and procedures are in place that guarantee client confidentiality

Health care providers provide adequate information and support, to enable each young person to make free and informed choices that are relevant to his or her individual needs, and:

are motivated to work with young people

are nonjudgmental, considerate, and easy to relate to

are able to devote adequate time to their patients

act in the best interests of their patients

Support staff are motivated to work with young people and are nonjudgmental, considerate, and easy to relate to

The point of delivery:

ensures privacy (including discreet entrance)

ensures consultations occur in a short waiting time, with or without an appointment, and (where necessary) swift referral

lacks stigma

has an appealing and clean environment

has an environment that ensures physical safety

provides information with a variety of methods

Young people are actively involved in the assessment and provision of health services

The appropriateness of health services for young people is best achieved if:

Health services needed to fulfill the needs of all young people are provided, either at the point of delivery or through referral links

Health care providers deal adequately with a presenting issue, yet strive to go beyond it, to address other issues that affect the health and development of adolescent patients

The effectiveness of health services for young people is best achieved if:

Health care providers have required skills

Health service provision is guided by technically sound protocols and guidelines

Points of service delivery have necessary equipment, supplies, and basic services to deliver needed health services

References

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Consultation on Adolescent Health Services: A Consensus StatementGenevaWHO2001

- World Health OrganizationAdolescent Friendly Health Services: Making It HappenGenevaWHO2005

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationAdolescent pregnancy2014 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/enAccessed August 10, 2016

- SedghGFinerLBBankoleAEilersMASinghSAdolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trendsJ Adolesc Health201556222323025620306

- HoffmanSDMaynardRAKids Having kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy2nd edWashingtonUrban Institute Press2008

- PalermoTBleckJWestleyEKnowledge and use of emergency contraception: a multicountry analysisInt Perspect Sex Reprod Health2014402798625051579

- BarotSPast due: emergency contraception in U.S. reproductive health programs overseasGuttmacher Policy Rev2010132811

- American Society for Emergency ContraceptionInching towards progress: ASEC’s 2015 Pharmacy Access Study2015 Available from: http://americansocietyforec.org/uploads/3/2/7/0/3270267/asec_2015_ec_access_report_1.pdfAccessed August 10, 2016

- ClelandKZhuHGoldstuckNChengLTrussellJThe efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experienceHum Reprod20122771994200022570193

- TurokDKGodfreyEMWojdylaDDermishATorresLWuSCCopper T380 intrauterine device for emergency contraception: highly effective at any time in the menstrual cycleHum Reprod201328102672267623945595

- World Health OrganizationSelected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use2nd edGenevaWHO2004

- World Health OrganizationEmergency contraception2016 Available from: http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs244/enAccessed August 10, 2016

- Society for Adolescent Health and MedicineEmergency contraception for adolescents and young adults: guidance for health care professionalsJ Adolesc Health201658224524826802996

- BracheVCochonLJesamCImmediate pre-ovulatory administration of 30 mg ulipristal acetate significantly delays follicular ruptureHum Reprod20102592256226320634186

- GlasierAFCameronSTFinePMUlipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysisLancet2010375971455556220116841

- Gemzell-DanielssonKBergerCLalitkumarPGMechanisms of action of oral emergency contraceptionGynecol Endocrinol2014301068568725117156

- GlasierACameronSTBlitheDCan we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrelContraception201184436336721920190

- MoreauCTrussellJResults from pooled phase III studies of ulipristal acetate for emergency contraceptionContraception201286667368022770793

- AhernRFrattarelliLADeltoJKaneshiroBKnowledge and awareness of emergency contraception in adolescentsJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201023527327820537573

- YenSParmarDDLinELAmmermanSEmergency contraception pill awareness and knowledge in uninsured adolescents: high rates of misconceptions concerning indications for use, side effects, and accessJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol201528533734226148784

- SahinNHMale university students’ views, attitudes and behaviors towards family planning and emergency contraception in TurkeyJ Obstet Gynaecol Res200834339239818686357

- BaldwinSBSolorioRWashingtonDLYuHHuangYCBrownERWho is using emergency contraception? Awareness and use of emergency contraception among California women and teensWomens Health Issues200818536036818774454

- CallahanSTCooperWOUninsurance and health care access among young adults in the United StatesPediatrics20051161889515995037

- IrwinCEJrAdamsSHParkMJNewacheckPWPreventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get servicesPediatrics20091234e565e57219336348

- MollenCJBargFKHayesKLGotcsikMBladesNMSchwarzDFAssessing attitudes about emergency contraception among urban, minority adolescent girls: an in-depth interview studyPediatrics20081222e395e40118676526

- WhittakerPGBergerMArmstrongKAFeliceTLAdamsJCharacteristics associated with emergency contraception use by family planning patients: a prospective cohort studyPerspect Sex Reprod Health200739315816617845527

- SampsonONavarroSKKhanABarriers to adolescents’ getting emergency contraception through pharmacy access in California: differences by language and regionPerspect Sex Reprod Health200941211011819493220

- SalazarMOhmanAWho is using the morning-after pill? Inequalities in emergency contraception use among ever partnered Nicaraguan women: findings from a national surveyInt J Equity Health2014136124989177

- PhippsMGMattesonKAFernandezGEChiaveriniLWeitzenSCharacteristics of women who seek emergency contraception and family planning servicesAm J Obstet Gynecol20081992111.e111e11518355784

- HalpernCTMitchellEMFarhatTBardsleyPEffectiveness of web-based education on Kenyan and Brazilian adolescents’ knowledge about HIV/AIDS, abortion law, and emergency contraception: findings from TeenWebSoc Sci Med200867462863718556101

- SchwarzEBGerbertBGonzalesRComputer-assisted provision of emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trialJ Gen Intern Med200823679479918398664

- Falah-HassaniKKosunenEShiriRRimpelaAEmergency contraception among Finnish adolescents: awareness, use and the effect of non-prescription statusBMC Public Health2007720117688702

- ChofakianCBBorgesALSatoAPAlencarGPSantosOAFujimoriEDoes the knowledge of emergency contraception affect its use among high school adolescents?Cad Saude Publica2016321e00188214

- WuJGipsonTChinNWomen seeking emergency contraceptive pills by using the internetObstet Gynecol20071101445217601895

- GoldenNHSeigelWMFisherMEmergency contraception: pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes, and opinionsPediatrics2001107228729211158460

- BaturPClelandKMcNamaraMWuJPickleSEmergency contraception: a multispecialty survey of clinician knowledge and practicesContraception201693214515226363429

- GilliamMLDavisSDNeustadtABLeveyEJContraceptive attitudes among inner-city African American female adolescents: barriers to effective hormonal contraceptive useJ Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol20092229710419345915

- RaymondEGTrussellJPolisCBPopulation effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic reviewObstet Gynecol2007109118118817197603

- FitterMUrquhartRAwareness of emergency contraception: a followup reportJ Fam Plann Reprod Health Care200834211111318413025

- DanielsKJonesJAbmaJUse of emergency contraception among women, aged 15–44: United States, 2006–2010NCHS Data Brief201311218

- SoonJAMeckleyLMLevineMMarcianteKDFieldingDWEnsomMHModelling costs and outcomes of expanded availability of emergency contraceptive use in British ColumbiaCan J Clin Pharmacol2007143e326e33818180535

- TrussellJRaymondEGClelandKEmergency Contraception: A Last Chance to Prevent Unintended PregnancyPrinceton (NJ)Princeton University2016

- CatalanoRFFaganAAGavinLEWorldwide application of prevention science in adolescent healthLancet201237998261653166422538180

- No authors listedWho is responsible for adolescent health?Lancet20043639426200915207945

- StricklandBMcPhersonMWeissmanGvan DyckPHuangZJNewacheckPAccess to the medical home: results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care NeedsPediatrics20041135 Suppl1485149215121916

- KangMBernardDUsherwoodTBetter Practice in Youth Health: Final Report on Research Study Access to Health Care among Young People in New South Wales – Phase 2SydneyUniversity of Sydney2005

- ToometKPartKHaldreKA decade of youth clinics in EstoniaEntre Nous Cph Den20045856

- BrindisCDKleinJSchlittJSantelliJJuszczakLNystromRJSchool-based health centers: accessibility and accountabilityJ Adolesc Health2003326 Suppl9810712782448

- NorthSWMcElligotJDouglasGMartinAImproving access to care through the patient-centered medical homePediatr Ann2014432e33e3824512159

- World Health OrganizationAdolescent Friendly Health Services: An Agenda for ChangeGenevaWHO2002

- MayernikDResickLKSkomoMLMandockKParish nurse-initiated interdisciplinary mobile health care delivery projectJ Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs2010392227234

- HillCZurakowskiDBennetJKnowledgeable Neighbors: a mobile clinic model for disease prevention and screening in underserved communitiesAm J Public Health2012102340641022390503

- EdgerleyLPEl-SayedYYDruzinMLKiernanMDanielsKIUse of a community mobile health van to increase early access to prenatal careMatern Child Health J200711323523917243022

- TyleeAHallerDMGrahamTChurchillRSanciLAYouth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done?Lancet200736995721565157317482988

- Pathfinder InternationalMaking Reproductive Health Services Youth FriendlyWashingtonFocus on Young Adults1999

- World Health OrganizationQuality Assessment Guidebook: A Guide to Assessing Health Services for Adolescent ClientsGenevaWHO2009

- BearingerLHSievingREFergusonJSharmaVGlobal perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potentialLancet200736995681220123117416266

- Paul-EbhohimhenVAPoobalanAvan TeijlingenERA systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan AfricaBMC Public Health20088418179703

- ThatoRJenkinsRADusitsinNEffects of the culturally-sensitive comprehensive sex education programme among Thai secondary school studentsJ Adv Nurs200862445746918476946

- KirbyDObasiALarisBAThe effectiveness of sex education and HIV education interventions in schools in developing countriesWorld Health Organ Tech Rep Ser2006938103150 discussion 317–34116921919

- United NationsA WORLD FIT FOR US- Message from the Children’s Forum, delivered to the UN General Assembly Special Session on Children by child delegates, Gabriela Azurduy Arrieta, 13, from Bolivia and Audrey Cheynut, 17, from Monaco on 8 May 2002 Available from: https://www.unicef.org/specialsession/documentation/childrens-statement.htmAccessed November 16, 2016