Abstract

Although the Achilles tendon (AT) is the strongest tendon in the human body, rupture of this tendon is one of the most common sports injuries in the athletic population. Despite numerous nonoperative and operative methods that have been described, there is no universal agreement about the optimal management strategy of acute total AT ruptures. The management of AT ruptures should aim to minimize the morbidity of the injury, optimize rapid return to full function, and prevent complications. Since endoscopy-assisted percutaneous AT repair allows direct visualization of the synovia and protects the paratenon that is important in biological healing of the AT, this technique becomes a reasonable treatment option in AT ruptures. Furthermore, Achilles tendoscopy technique may decrease the complications about the sural nerve. Also, early functional postoperative physiotherapy following surgery may improve the surgical outcomes.

Introduction

It is well known that the Achilles tendon (AT) has a high capacity to withstand tensional forces created by the movements of the human body, and so it is the strongest and thickest tendon in the human body.Citation1,Citation2 In spite of its size and strength, there is a high incidence of AT injuries, and it has been stated that 6%–18% of all sporting injuries involve the AT. AT ruptures commonly occur during sporting activities; furthermore, there is a tendency of increase in the incidence of ruptures because of ‘weekend warriors’ who are over 30 years of age. AT ruptures are reported as the third most frequent major tendon rupture, following rotator cuff and quadriceps ruptures.Citation3,Citation4 Despite numerous nonoperative (casting or functional bracing) and operative methods, optimal treatment of AT ruptures remains controversial, and management is still determined by the preferences of the surgeon and the patient.

To date, clinical studies have focused on cast immobilization, open surgical repair, and minimally invasive percutaneous repair. Cast immobilization may lead to suboptimal healing, with elongation of the tendon; however, reduced strength of the calf muscles and unacceptably high rate of rerupture with an incidence up to 39% seem major disadvantages of this modality.Citation5–Citation10 Open surgical repair of the AT is the commonly preferred method, but it carries specific risks, including adhesions between the tendon and the skin, infection, and particularly wound breakdown.Citation11–Citation13 The advantages of the operative and conservative methods are combined in minimally invasive percutaneous repair technique, and this technique has become popular in recent years. The major disadvantages of percutaneous repair technique are not being able to direct visualization of the tendon ends and complications about sural nerve entrapment; however, these problems may be overcome by performing the percutaneous repair under endoscopic control.Citation14–Citation16 Application of autologous growth factors also seems promising to improve the potential of biological tissue healing response.Citation17–Citation21 One of the keystones of a successful treatment is early physiotherapy after surgical approach.

Endoscopy-assisted percutaneous repair

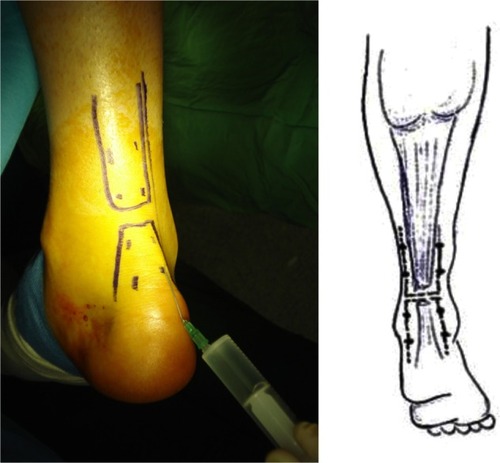

The operation is performed with the patient in the prone position and under local infiltration anesthesia without a tourniquet. There is no need to administer antibiotic or antithrombotic prophylaxis. Before starting the procedure, the rupture site and location of the gap are marked (). Subsequently, to minimize local bleeding, proximal (about 5 cm) and distal (about 4 cm) to the palpated gap, the skin, the subcutaneous tissues, and the peritendon are infiltrated with 20–50 mL 0.9% saline solution with local anesthetic (1% Citanest® 5 mL + 0.5% Marcain® 5 mL) around the eight planned stab wounds, four medial and four lateral to the tendon, distributed evenly proximally and distally to the ruptured area (). No other medications, nerve blocks, or other types of anesthetics are administered.

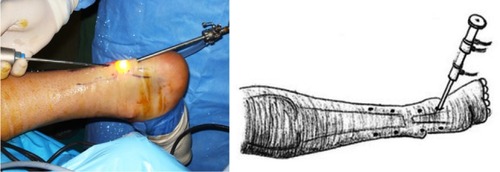

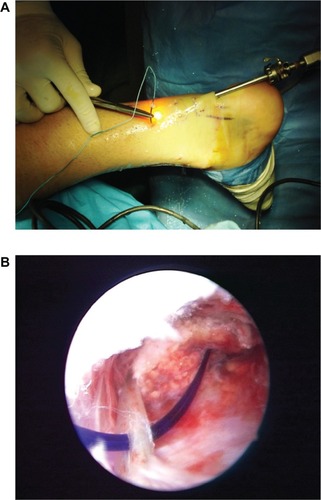

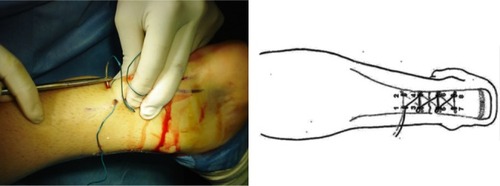

Using the nick and spread technique, these puncture holes are later enlarged and used for needle entry. Special attention is paid to the lateral AT area, especially proximally, where the sural nerve lies close to and crosses the AT. During the injection of local anesthetic or at any time during the procedure, the patient is prompted to report any paresthesia or pain in the area of distribution of the sural nerve. If pain is reported, the injection site is shifted 0.5–1 cm toward the midline. The tendon and paratenon are examined with a 30° arthroscope (Smith and Nephew, London, UK) via the distal medial incision, and the injured foot is positioned in ~15° of plantar flexion (). After the level of the rupture has been determined, the continuity of the surrounding tissues together with their consistency and vascularization are evaluated. The torn ends of the AT are inspected and, if necessary, are manipulated within the paratenon. The passing of the suture through the AT is also controlled with the scope. In this study, we used an Ethibond No. 5 or PDS No. 5 (Ethicon Inc, Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, NJ) suture with a modified Bunnell configuration. The needle with the PDS or Ethibond suture is first introduced through the upper medial portal (, B). To ensure that the AT is caught fully by the needle, the tendon is gently palpated between the thumb and the index finger of the opposite hand. This first bite is a transverse one, and the needle emerges from the upper lateral portal (). The needle is then retrieved, introduced again through it, and passed through the upper lateral portal toward portal 3. The procedure is repeated in a proximal-to-distal direction going from portal 3 to portal 4, from portal 4 to portal 5, from portal 5 to portal 6, from portal 6 to portal 7, and from portal 7 to portal 8, the distal-most lateral portal. At this point, the needle is retrieved from portal 8, introduced through it, and passed through the distal-most lateral portal toward portal 5, and the procedure described above is repeated backward in a distal-to-proximal direction until the needle is finally returned to the upper medial portal (). First, we pass the suture from the proximal medial incision and out from the medial incision just above the ruptured tendon, making sure that the body of the proximal stump of the tendon is squeezed between the thumb and the index fingers (). Second, we pass the suture from the same incision and out from the lateral stab incision just above the tendon (). Finally, as in the first step, the suture is passed through this distal stab incision, carried to proximal, and then out from the superior medial side again (). During the suture passage, the arthroscope is placed alternatively in the various entry portals, and the AT is inspected from the medial and lateral aspects. The proximal and distal stumps are also inspected from proximal and distal directions to make sure that the tendon stumps are juxtaposed. Through the endoscope, we also ensured that the sutures are presented in the tendon at different levels on the coronal plane so that the chance of them cutting through is minimized during the process of tensioning. Finally, the sutures are tensioned and tied in the proximal medial entry portal with the ankle in neutral position while checking the tendon approximation through the arthroscope. Before tying the sutures with the ankle in neutral position, the patient is instructed to actively dorsi-and plantar-flex the ankle with the knee at 90° of flexion to make sure that appropriate tension is imparted to the suture (). A final check is performed, and the suture is fully knotted and no drainage is used. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is prepared by withdrawing the patients’ peripheral blood and centrifuging to obtain a highly concentrated sample of platelets, which undergo degranulation to release growth factors with healing properties. Following PRP injection to the ruptured site (), the skin stab incisions are closed with subcutaneous suture, and Steri-Strips (3M Nexcare, St Paul, MN) are used for initial dressing (). A walking brace is then applied with the ankle in the neutral position for at least 3 weeks.

Figure 4 A modified Bunnel suture configuration was used for the procedure. A) Initially, the suture passes from the superomedial stab incision (portal 1). B) The suture is carried distally with zig-zag fashion in the sequence of the number of the stab incisions under control of endoscopy.

Figure 5 Final step for suturing process is carrying the suture to proximal and then out from the superomedial portal again (portal 1).

Physiotherapy

A standard rehabilitation program for percutaneous repair of AT, developed based on literature in the Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinic, Hacettepe University, is initiated immediately (). Patients are encouraged to weight-bearing ambulation with a walking brace-moon boot as tolerated (for 3 weeks only), alternating with a passive range of motion exercises. Physiotherapy, including electrical stimulation of the gastrosoleus muscle complex, cryotherapy, and therapeutic ultrasound, is applied around the AT for reduction of edema. Transverse friction massage is used to promote scar and tendon reformation. Patients are instructed to move the ankle four times a day between 20° of plantar flexion and 10° of dorsiflexion. The patients are requested to complete gentle isometric, eccentric, and concentric exercises of the ankle several times a day, with flexion and extension of the toes in a supine position and full plantar flexion and dorsiflexion of the ankle to neutral in a supine position, extension of the knee in a sitting position, flexion of the knee in a prone position, and extension of the hip in a prone position within the first 3 weeks. Full weight bearing is allowed after 3 weeks postoperatively without brace. From the 6th to 10th week, rehabilitation progresses to using elastic resistance bands; rotation of the ankles; standing on the toes and heels; ankle-stretching exercises to flexion with the help of a rubber band; stretching of the calf muscle by standing with the leg to be stretched straight behind and the other leg bent in front and leaning the body forward, with support from a wall or physiotherapist; stretching exercises for the toes and ankle against manual resistance in a sitting position; balance and proprioception exercises on different surface progress from bilateral to unilateral; and controlled squats, lunges, bilateral calf raise (progressing to unilateral), toe raises, controlled slow eccentrics versus body weight. After 10 weeks, patients are allowed training jogging/running, jumping and eccentric loading exercises, noncompetitive sporting activities, sports-specific exercises, and returning to physically demanding sports and/or work.

Table 1 Rehabilitation protocol following endoscopy-assisted percutaneous Achilles tendon repair

Discussion

Although ruptures of the AT are a relatively common injury encountered by the orthopedic surgeon, the incidence in the general population is difficult to determine but it is well known that most ruptures (44%–83%) of the AT occur during sports activities.Citation2,Citation22,Citation23 Therefore, rupture of the AT is more common in males, with a male-to-female ratio ranging from 1.7:1 to 12:1, possibly reflecting the greater prevalence of males than females who are involved in sports. Typically, acute ruptures of the AT occur in men in the third or fourth decade of life, particularly those who work in a white-collar profession and play a sport occasionally.Citation2,Citation24

Despite many studies and meta-analyses due to increasing incidence of the AT rupture, there is no consensus about the optimal management strategy of acute total AT rupture.Citation8,Citation25–Citation27 Many techniques and procedures described for the treatment of ruptured AT can be grouped under three headings: open operative, percutaneous operative, and nonoperative.

The first description of the treatment of acute AT rupture is attributed to Ambroise Paré in 1575, and he recommended that a ruptured AT be strapped with bandages dipped in wine and spices, but the results were dubious.Citation2 Operative repair of a ruptured AT was advocated first in 1888 by Gustave Polaillon.Citation2 But before the 20th century, AT ruptures were treated nonoperatively.Citation28 However, in the early 20th century, following the level IV study by AbrahamsenCitation29 as well as Quenu and Stoinovitch,Citation30 surgical repair of acute Achilles ruptures became more common.

There are several publications that support conservative treatment, but operative treatment modalities have been the method of choice in the last 3 decades especially for athletes and young people. The most commonly used form of nonoperative treatment is immobilization in a plaster cast, usually for a period of 6–8 weeks. These authors suggested that operative repair of a ruptured AT should be avoided, as stripping of the paratenon during an operation reduces the amount of reactive tissue that is produced later at the site of the injury, and the paratenon provides a valuable blood supply to the damaged tendon. However, conservative treatment has less functional results with higher rerupture rates and hence should be kept for elderly and low-demanding patients.Citation31 In a systematic review, the probability of rerupture from nonoperative management was reported as 12.1%.Citation32 A primary goal of the treatment of a rupture of the AT is to avoid lengthening of the tendon, and this cannot be achieved with nonoperative treatment.

Afterward, reduced complication rates and improved functional outcomes led many surgeons to again advocate surgical repair of acute Achilles ruptures. Numerous open surgical procedures have been proposed for repairing ruptures of the AT, ranging from simple end-to-end suturing, with Bunnell or Kessler-type sutures, to more complex repairs with use of fascial reinforcement or tendon grafts. In addition to these artificial tendon implants, materials such as absorbable polymer-carbon fiber composites, Marlex mesh (monofilament knitted polypropylene), and collagen tendon prostheses have also been used.Citation2 Even though operative regimens present a lower rerupture rate, early functional rehabilitation, and stronger push off with a lower calf atrophy,Citation8,Citation10,Citation25,Citation28,Citation32,Citation33 open surgical repair also includes potential problems like joint stiffness, calf muscles atrophy, tendocutaneous adhesions, deep venous thrombosis due to prolonged immobilization, infection, scarification, algodysthrophie, and particularly the breakdown of the wound.Citation11,Citation32,Citation34–Citation37

Percutaneous repair technique was first described by Ma and GriffithCitation33 to avoid all these complications, and this technique has become a popular technique for orthopedic surgeons. However, the technique involves difficulties in achieving satisfactory contact of the tendon stumps and adequate initial fixation. Percutaneous suturing is criticized because it provides ~50% of the initial strength afforded by open repair and has a higher rate of rerupture (6.4%) than open operative repair.Citation38,Citation39 Webb and BannisterCitation38 define percutaneous repair technique as a three-midline stab incision over the posterior aspect of the tendon in order to avoid sural nerve injury, and Wagnon and AkayiCitation40 report that this method is an effective option with functional and radiological outcomes, sural nerve entrapment seems to be a potential complication of this technique.Citation8,Citation33 Cadaveric dissections with computer-assisted modeling in the sagittal and transverse planes showed that the sural nerve crossed the AT at, on average, 11 cm proximal to the calcaneal tubercle and, on average, 3.5 cm distal to the musculotendinous junction.Citation41 Therefore, in this area, the nerve is especially vulnerable to iatrogenic injury during surgery, particularly minimally invasive surgery.Citation41,Citation42 Since minimally invasive percutaneous repair techniques do not provide direct observation, percutaneous repair of AT rupture under endoscopic control has been suggested to overcome this blindness.Citation15,Citation16,Citation43,Citation44

Major advantages of endoscopy-assisted percutaneous repair are allowing direct observation of the process of suturing the AT and eliminating some of the disadvantages of the percutaneous repair techniques, especially the evaluation of the juxtaposition of the torn ends.Citation15,Citation38,Citation45–Citation47 Since this technique allows early active ankle mobilization and weight bearing after a short period of cast immobilization, complications due to the prolonged immobilization may be prevented. Another important issue in this technique is that it could help to prevent the risk of damage to the sural nerve by allowing its direct visualization. However, knowledge of the local anatomy is crucial to place the stab wounds in the areas less likely to damage the sural nerve ().Citation1 Since the paratenon is protected in endoscopic repair, biological advantage to the mechanical strength of the repair furnished by the suture material could be provided. Preservation of paratenon also decreases the gliding resistance of the extrasynovial tendons after repetitive motion, as in the example of synovial covering in the healing process of the posterior cruciate ligament, where a mechanically strong AT is achieved.Citation48 Furthermore, Achilles tendoscopy technique allows direct observation of the stab wounds and controlled juxtaposition of the tendon ends without damaging the paratenon.Citation49 Doral et alCitation27 highlighted the importance of endoscopic repair in protecting paratenon on biological healing of the AT ruptures. Since the paratenon is weak, our sutures may be more effective than biological healing in ruptures associated with Achilles tendinosis.Citation14

Figure 9 Cadaveric dissection of the Achilles tendon (AT). Sural nerve lies at the lateral border of the AT.

Cretnik et alCitation35 and Lim et alCitation37 compared the results of percutaneous versus open AT repair in prospective randomized studies and emphasized that the percutaneous technique brings comparable functional results, with significantly lower complication rates and improved cosmetic appearance.

Buchgraber and PässlerCitation50 compared the results of immobilization and functional postoperative treatment after using a standardized microinvasive technique for AT rupture. Their results revealed that patients undergoing functional postoperative rehabilitation with early weight bearing were hospitalized for shorter periods and lost fewer days from work than those in the cast group and had less severe calf muscle work by the injured leg than postoperative immobilization. The rerupture rate was reported no higher than after cast immobilization, but lower than after open surgical repair or conservative functional treatment alone.Citation50 Similarly, Majewski et alCitation51 compared postoperative below-knee cast immobilization and early functional therapy using a special shoe following percutaneous repair of acute AT ruptures. Results indicated that early mobilization in a special shoe provides a good clinical outcome and shortens the time for return to work and sports, so it is preferable to postoperative immobilization after percutaneous AT repair.

Carmont and MaffulliCitation47 recommended a mini open technique, with a 1.2–1.5 cm transverse incision at the level of the rupture, to directly observe whether the appropriate juxtaposition of the ruptured tendon ends has been achieved. This method of percutaneous repair permits a less invasive approach to the tendon and accurate opposition of the tendon ends and minimizes the chance of sural nerve injury. Although the main disadvantage of this procedure is requirement of experience on soft tissue endoscopy, we recommend practicing this technique on cadavers or amputated limbs before clinical application.Citation52

New techniques utilizing growth factors may offer the biological potential to enhance the quality and biomechanical integrity of healing knee ligaments.Citation17,Citation18 In vitro studies suggested that growth factors (PRP injections) released by platelets recruit reparative cells and may augment soft tissue repair.Citation19,Citation21 Sánchez et alCitation17 reported the operative management of tendons combined with the application of autologous growth factors also seems promising to improve tissue healing response and functional recovery. To accelerate the healing response and revascularization of ruptured tendon, PRP, prepared by withdrawal of patients’ peripheral blood and centrifugation to obtain a highly concentrated sample of platelets, was injected to the ruptured site of the AT. Although randomized controlled trials are necessary to claim the effects of growth factors, the use of autologous PRP is shown to be safe, reproducible, and effective in mimicking the natural processes of soft tissue and bone healing.

Conclusion

Percutaneous repair of the AT under endoscopic control with local infiltration anesthesia is a safe method when compared with open surgery or minimally invasive approaches. It is likely more cost-effective than open techniques, and, in some settings, endoscopic control carries no additional costs. Also, this technique results in excellent wound appearance without any severe complication (). Furthermore, this procedure protects the paratenon and thus blood supplies of the tendon and should enhance biologic recovery. Direct visualization and manipulation of the tendon ends also provide stable repair that allows early weight bearing and ambulation and can be used in athletic individuals.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DoralMNAlamMBozkurtMFunctional anatomy of the Achilles tendonKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc201018563864320182867

- MaffulliNRupture of the Achilles tendonJ Bone Joint Surg (Am)19998171019103610428136

- HattrupSJJohnsonKAA review of ruptures of the Achilles tendonFoot Ankle19856134383899877

- LipscombPRWeinerADRupture of muscles and tendonsMinn Med1956391173173613378248

- JacobsDMartensMvan AudekerckeRMulierJCMulierFComparison of conservative and operative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptureAm J Sports Med197863107111655329

- EdnaTHNon-operative treatment of Achilles tendon rupturesActa Orthop Scand19805169919937211305

- FierroNSallisREAchilles tendon rupture. Is casting enough?Postgrad Med19959831451527675738

- MöllerMMovinTGranhedHLindKFaxénEKarlssonJAcute rupture of tendo Achillis. A prospective randomized study of comparison between surgical and non-surgical treatmentJ Bone Joint Surg Br200183684384811521926

- WillsCAWashburnSCaiozzoVPriettoCAAchilles tendon rupture. A review of the literature comparing surgical versus nonsurgical treatmentClin Orthop Relat Res19862071561633720080

- WongJBarrassVMaffulliNQuantitative review of operative and nonoperative management of Achilles tendon rupturesAm J Sports Med200230456557512130412

- BhandariMGuyattGHSiddiqueFTreatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a systematic overview and metaanalysisClin Orthop Relat Res200240019020012072762

- BradleyJPTiboneJEPercutaneous and open surgical repairs of Achilles tendon ruptures. A comparative studyAm J Sports Med19901821881952188518

- EbinesanADSaraiBSWalleyGDMaffulliNConservative, open or percutaneos repair for acute rupture of the Achilles tendonDisabil Rehabil20083020–221721172518608405

- DoralMNBozkurtMTurhanEPercutaneous suturing of the ruptured Achilles tendon with endoscopic controlArch Orthop Trauma Surg200912981093110119404654

- TangKLThermannHDaiGChenGXGuoLYangLArthroscopically assisted percutaneous repair of fresh closed Achilles tendon rupture by Kesslers sutureAm J Sports Med200735458959617170162

- ThermannHTibeskuCOMastrokalosDSPässlerHHEndoscopically assisted percutaneous Achilles tendon sutureFoot Ankle Int200122215816011249228

- SánchezMAnituaEAzofraJAndíaIPadillaSMujikaIComparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matricesAm J Sports Med200735224525117099241

- Lopez-VidrieroEGouldingKASimonDASanchezMJohnsonDHThe use of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopy and sports medicine: optimizing the healing environmentArthroscopy201026226927820141991

- de MosMvan der WindtAEJahrHCan platelet-rich plasma enhance tendon repair? A cell culture studyAm J Sports Med20083661171117818326832

- KashiwagiKMochizukiYYasunagaYIshidaODeieMOchiMEffects of transforming growth factor-beta 1 on the early stages of healing of the Achilles tendon in a rat modelScand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg200438419319715370799

- AspenbergPVirchenkoOPlatelet concentrate injection improves Achilles tendon repair in ratsActa Orthop Scand2004751939915022816

- SuchakABostickGReidDBlitzSJomhaNThe incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in Edmonton, CanadaFoot Ankle Int2005261193293616309606

- CettiRChristensenSEEjstedRJensenNMJorgensenUOperative versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective randomized study and review of the literatureAm J Sports Med19932167917998291628

- SargonMFOzluKOkenFAge-related changes in human tendo calcaneus collagen fibrilsSaudi Med J200526342542815806212

- KhanRJFickDKeoghACrawfordJBrammarTParkerMTreatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. A metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trialsJ Bone Joint Surg Am200587102202221016203884

- MajewskiMRickertMSteinbrückKAchilles tendon rupture. A prospective study assessing various treatment possibilitiesOrthopade200029767067610986713

- DoralMNTetikOAtayOALeblebicioğluGOznurAAchilles tendon diseases and its managementActa Orthop Traumatol Turc200236Suppl 1424612510123

- ChiodoCPDen HartogBSurgical strategies: acute Achilles ruptureopen repairFoot Ankle Int200829111411818275750

- AbrahamsenKRuptura tendinis AchillisUgesskr Laeger192385279285

- QuenuJStoinovitchSLes ruptures du tendon d’AchilleRev Chir192948647678

- LeaRBSmithLNon-surgical treatment of tendo Achilles ruptureJ Bone Joint Surg1972547139814074655535

- KocherMSBishopJMarshallRBriggsKKHawkinsRJOperative versus nonoperative management of acute Achilles tendon rupture: expected-value decision analysisAm J Sports Med200230678379012435641

- MaGWCGriffithTGPercutaneous repair of acute closed ruptured Achilles tendon. A new techniqueClin Orthop1977128247255340096

- LiJXuYWangXManagement of soft tissue defect after Achilles tendon repairZhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi200721436737017546880

- CretnikAKosanovicMSmrkoljVPercutaneous versus open repair of the ruptured Achilles tendon: a comparative studyAm J Sports Med20053391369137915827357

- ChiodoCPWilsonMGCurrent concepts review: acute ruptures of the Achilles tendonFoot Ankle Int200627430531316624224

- LimJDalalRWaseemMPercutaneous vs open repair of the ruptured Achilles tendon – a prospective randomized controlled studyFoot Ankle Int200122755956811503980

- WebbJMBannisterGCPercutaneous repair of the ruptured tendo AchillisJ Bone Joint Surg (Br)199981587788010530854

- HockenburyRTJohnsJCA biomechanical in vitro comparison of open versus percutaneous repair of tendon AchillesFoot Ankle199011267722265811

- WagnonRAkayiMThe Webb-Bannister percutaneous technique for acute Achilles’ tendon ruptures: a functional and MRI assessmentJ Foot Ankle Surg200544643744416257672

- CitakMKnoblochKAlbrechtKKrettekCHufnerTAnatomy of the sural nerve in a computer-assisted model: implications for surgical minimal-invasive Achilles tendon repairBr J Sports Med2007417456458 discussion 45817347315

- ApaydinNBozkurtMLoukasMVefaliHTubbsRSEsmerAFRelationships of the sural nerve with the calcaneal tendon: an anatomical study with surgical and clinical implicationsSurg Radiol Anat2009529 [Epub ahead of print]

- FortisAPDimasALamprakisAARepair of Achilles tendon rupture under endoscopic controlArthroscopy200824668368818514112

- LuiTHEndoscopic-assisted Achilles tendon repair with plantaris tendon augmentationArthroscopy2007235556 e1–556.e517478289

- HalasiTTállayABerkesIPercutaneous Achilles tendon repair with and without endoscopic controlKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc200311640941414530847

- RebeccatoASantiniSSalmasoGNogarinLRepair of the Achilles tendon rupture: a functional comparison of three surgical techniquesJ Foot Ankle Surg200140418819411924679

- CarmontMRMaffulliNModified percutaneous repair of ruptured Achilles tendonKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc200816219920317874233

- McClellandDMaffulliNPercutaneous repair of ruptured Achilles tendonJ R Coll Surg Edinb200247461361812363186

- MomoseTAmadioPCZobitzMEZhaoCAnKNEffect of paratenon and repetitive motion on the gliding resistance of tendon of extrasynovial originClin Anat200215319920511948955

- BuchgraberAPässlerHHPercutaneous repair of Achilles tendon rupture. Immobilization versus functional postoperative treatmentClin Orthop Relat Res19973411131229269163

- MajewskiMSchaerenSKohlhaasUOchsnerPEPostoperative rehabilitation after percutaneous Achilles tendon repair: early functional therapy versus cast immobilizationDisabil Rehabil20083020–221726173218720131

- TurgutAGünalIMaralcanGKöseNGöktürkEEndoscopy assisted percutaneous repair of the Achilles tendon ruptures: a cadaveric and clinical studyKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc200210213013311914773