Abstract

Previous research offers evidence that psychological factors influence an injured athlete during the rehabilitation process. Our first objective was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the results from all published studies that examined the relationships among negative affective responses after sport injuries, rehabilitation adherence, and return to play (RTP). The second objective was to use a meta-analytic path analysis to investigate whether an indirect effect existed between negative affective responses and RTP through rehabilitation adherence. This literature review resulted in seven studies providing 14 effect sizes. The results from the meta-analysis showed that negative affective responses had a negative effect on successful RTP, whereas rehabilitation adherence had a positive effect on RTP. The results from the meta-analytic path analysis showed a weak and nonsignificant indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP via rehabilitation adherence. These results underline the importance of providing supportive environments for injured athletes to increase the chances of successful RTP via a decrease in negative affective responses and increase in rehabilitation adherence.

Introduction

Sport injuries are a major problem related to sport participation.Citation1–Citation3 Research has shown that injuries can have major negative consequences on an athlete’s athletic career (e.g., career termination)Citation4,Citation5 and can severely affect his/her well-being.Citation6–Citation8 Given the potential negative outcomes related to sport injuries, one important aspect of sport injury rehabilitation is to facilitate the rehabilitation process to increase the chances of a successful rehabilitation outcome. To better understand the factors that might influence both the rehabilitation process and the likelihood of return to play (RTP), several theoretical frameworks have been developed. One theoretical framework developed to explain responses to sport injuries and the recovery process following sport injuries is the dynamic biopsychosocial cycles of post sport injury response and recovery framework.Citation9 According to this framework, an athlete’s interpretation of the situation of being injured will influence the magnitude of negative affective responses. The magnitude of negative affective responses is, in turn, suggested to influence an athlete’s behaviors (e.g., rehabilitation adherence). An athlete’s choice of behaviors will then be related to the rehabilitation outcomes (e.g., RTP). During the past 10 years, interest in psychological factors’ influences on the rehabilitation process and outcomes has progressively increased. This increased interest has resulted in several published review articles.Citation10–Citation15 One of the main conclusions of these reviews is that negative psychological responses can decrease the likelihood of a successful RTP.

In these review articles, however, only the direct effects of psychological variables on rehabilitation outcomes were examined; indirect effects have so far been neglected in the literature. This is a bit surprising because biological and rehabilitation behaviors have been suggested to mediate the relationship between psychological factors and rehabilitation outcomes.Citation9,Citation13 Given the suggestion that behaviors (e.g., rehabilitation adherence) mediate the relationship between psychological factors (e.g., affective responses) and rehabilitation outcomes (e.g., RTP), it is of interest to test the empirical support for this assumption.

Our first objective was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the results from all published studies that examined the relationships between negative affective responses after a sport injury, rehabilitation adherence, and RTP. The second objective was to use a meta-analytic path analysis to investigate the indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP through rehabilitation adherence.

Methods

Literature search

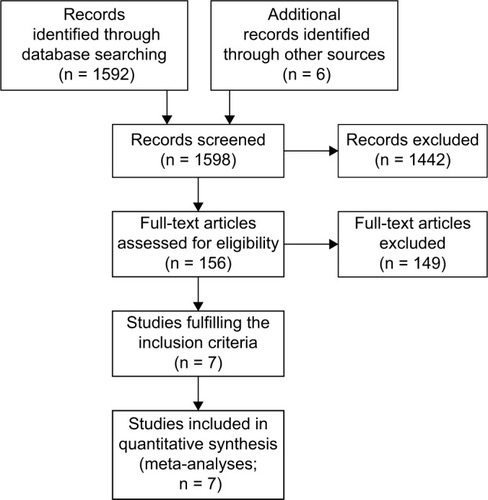

We searched the electronic databases of Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, and PsycINFO using combinations of the following keywords: “sport injury”, “psychology”, “return to play”, and “return to sport”. Boolean expressions and MeSH terms were used along with truncations adjusted to each database’s guidelines. In addition, we searched published review articles for additional studies.Citation10–Citation15

Studies were considered for inclusion if: 1) they had used prospective or cross-sectional designs; 2) they were published in peer-review journals; 3) they were written in English; 4) the athletes were injured when the first psychometric data were collected; and 5) they investigated any of the relationships between negative affective responses, adherence to rehabilitation, and RTP. In our study, different criteria were used for data extraction. The specific negative responses that Wiese-BjornstalCitation9 listed guided the selection of negative affective responses. For adherence to rehabilitation, subjective or objective reports on adherence to a prespecified rehabilitation plan were considered an inclusion criterion. RTP was defined as the length of time from the injury to the time when the athlete was playing sports again. One of the included studies, however, used a slightly different definition. Heredia et alCitation16 defined RTP as the length of time between the date when the athlete was declared medically fit and the date when the athlete returned to play. The Heredia et al study was, however, relevant to our research question and it was therefore included despite using a slightly different RTP definition. Effect sizes were calculated for relationships among the variables of interest (i.e., negative affective responses, adherence to rehabilitation, RTP). The full literature search process is illustrated in , and a summary of all studies included in the meta-analysis is reported in .

Table 1 Overview of the studies included in the meta-analysis

An additional inclusion criterion was that the studies presented statistical data necessary for the calculation of zero-inflated Pearson’s r effect sizes. Common reasons for the exclusion of studies were as follows: 1) the psychometric data were collected retrospectively, after the athletes had returned to sport activities; 2) the outcome variable was subjective knee function; and 3) the studies were review articles.

Meta-analytic procedures

By applying a meta-analytic procedure to a systematic review procedure, it is possible to collectively test a statistical synthesis of research findings. We used the zero-inflated correlation coefficients as effect-size estimates. In the calculation of the coefficients for the relationships among the three variables of interest, we first transformed all effect sizes to Fisher’s z correlations. In the second step, we corrected the Fisher’s z correlations by weighting the sample-size estimates. In the third step, we used the weighted Fisher’s z correlations to calculate the average Fisher’s z correlation for the relationships among the three variables. Fourth, we transformed the average Fisher’s z correlation into zero-inflated standardized correlation coefficients. For all calculations, we used the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software.Citation17 The results are reported using mean effect sizes (r) or beta (β) values in combination with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A result of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

We used the I2 statistic as a measure of heterogeneity among studies. The I2 estimate indicates the degree of inconsistency among the magnitudes of the coefficients within each category of relationships. We calculated a fail-safe number (FSN) for each relationship tested in the meta-analysis. The FSN is used to indicate how many additional studies with mean null results would be needed to reduce the combined statistical significance to a specific alpha level (e.g., 0.05).

Both Wiese-BjornstalCitation9 and BrewerCitation13 suggested that rehabilitation adherence potentially mediates the relationship between psychological variables and rehabilitation outcomes, and a meta-analytic path analysis is a useful approach for testing this proposed indirect association. To test the indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP via rehabilitation adherence, we conducted a meta-analytic path analysis within a meta-analysis structural equation modeling (MASEM) framework.Citation18 Prior to the analysis, we inserted the zero-inflated correlation coefficients into a correlation matrix. Based on this correlation matrix, we used Mplus version 7.4Citation19 to conduct the path analysis. To test the indirect effect, the Sobel method with a 95% CI was used. In addition, in line with previous recommendations, we used the harmonic mean as the sample size in our analysis.Citation20

Results

An overview of the study characteristics, heterogeneity assessment, and FSNs is provided in and . The results from the meta-analysis showed a negative and statistically significant relationship between negative affective responses after sport injury and RTP (r = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.42, −0.21]). Moreover, the relationship between rehabilitation adherence and RTP was positive and statistically significant (r = 0.54, 95% CI [0.34, 0.69]).

Table 2 Results of meta-analyses and homogeneity tests for the relationships between negative responses after injury, rehabilitation adherence, and return to sport

The results from the meta-analytic path analysis showed a statistically significant effect of negative affective responses on RTP (β = −0.26, 95% CI [−0.41, −0.12], p < 0.001). Also, a positive and statistically significant effect of rehabilitation adherence on RTP (β = 0.51, 95% CI [0.38, 0.64], p < 0.001) was found. Negative affective responses had a small and not statistically significant effect on rehabilitation adherence (β = −0.11, 95% CI [−0.29, 0.07], p = 0.23). Negative affective responses and rehabilitation adherence explained 36.0% of the variance in RTP, whereas negative affective responses explained 1.2% of the variance in rehabilitation adherence. The indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP via rehabilitation adherence was small and not statistically significant (standardized estimate = −0.06, 95% CI [−0.15, 0.04], p = 0.23).

Discussion

Both negative affective responses after injury occurrence and rehabilitation adherence had direct effects on RTP. More specifically, low levels of negative affective responses and high compliance with a rehabilitation program were associated with a higher likelihood of successful RTP. In addition, the results showed a weak, and not statistically significant, indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP.

The negative effect of negative affective responses on RTP has been found in previous studies.Citation21 One potential explanation for this relationship is that psychological stress seems to influence the wound-repair process.Citation22 More specifically, a meta-analysis showed a strong negative relationship between psychological distress and wound healing.Citation23 High stress levels are, for example, associated with physiological stress responses.Citation24 These stress responses can, in turn, retard the inflammatory phase and increase the risk of infection.Citation22 Another potential explanation for the relationship is that low levels of negative affective responses, such as anxiety and fear, will increase the likelihood of an athlete’s having confidence in the formerly injured body part.Citation25 An athlete with confidence in his/her body is probably more likely to return to sports at an earlier stage than an athlete who is not confident in that the body will cope with the physical load related to participation in the sport activity.

Only two of the studies included in the meta-analysis focused on the relationship between rehabilitation adherence and RTP. The magnitude of this effect should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, a strong positive effect of rehabilitation adherence on RTP was found. Compliance with a rehabilitation program, recommended by a physiotherapist, is one important aspect related to an increased chance of RTP.Citation26 Adhering to the recommended training program will increase the chance of the injured body part to recover and heal, which in turn will increase the chance of a successful comeback.

The path analysis showed that negative affective responses and rehabilitation adherence explained 36.0% of the variance in RTP. This result underlines the importance of considering psychological and behavioral factors in the injury rehabilitation process. There was a marginal, and not statistically significant, indirect effect of negative affective responses on RTP via rehabilitation adherence. This result contradicts the suggestion that behaviors will mediate the effect of negative affective responses on recovery as proposed in the dynamic biopsychosocial cycles of post sport injury response and recovery framework.Citation9 That psychological factors (e.g., emotions) have a causal, but often indirect, influence on behaviors has been shown in numerous studies in psychology.Citation27 The lack of a direct effect between negative affective responses and rehabilitation adherence (negative affective responses explained 1.2% of the variance in rehabilitation adherence) suggests that other variables might influence this relationship. Although a weak relationship (i.e., small effect size) was found between negative affective responses and rehabilitation adherence, associations might still exist between affective responses and other adaptive behaviors (e.g., help seeking, coping). Research on potentially adaptive behaviors other than rehabilitation adherence is warranted in future research.

Limitations and methodological considerations

This study has several limitations and methodological considerations that we want to address. First, the meta-analysis contains a small number of effect sizes. In particular, the estimate for the relationship between rehabilitation adherence and RTP as well as between negative affective responses and RTP (ks = 2 and 3) should be interpreted with caution because it is associated with low power.Citation28 Nevertheless, research has highlighted that the meta-analyses of a few studies may still provide important information.Citation29 Second, because few effect sizes were included in the analyses, no moderation analysis was possible to perform. Third, our decision to have RTP as our only rehabilitation outcome might have excluded studies that measured other relevant outcomes (e.g., knee function, pain). The reason for this decision was that we wanted to have an objective outcome that is meaningful for all members in the sporting community. Fourth, because we were interested in investigating both the direct and indirect paths among negative affective responses, rehabilitation adherence, and the dependent variable of RTP, we used a saturated model. The limitation of a saturated model is that it is impossible to evaluate model fit because this type of model always has perfect fit to data. A saturated model can be used if a researcher is “interested in estimating certain model parameters, with associated measures of instability.”Citation30

Conclusion and practical recommendations

The results showed that both negative affective responses and rehabilitation adherence are related to a successful RTP after a sport injury. More specifically, both low levels of negative affective responses and high compliance with a rehabilitation plan were predictors of a successful RTP. Athletes should, therefore, work with stress management techniques to decrease the level of negative affective responses during the rehabilitation process, which in previous research has been related to successful rehabilitation outcomes.Citation31,Citation32 Learning to take responsibility and to view an injury as a challenge instead of as a threat (problem-focused coping) has been one successful strategy. For practitioners, it is important to design an environment that decreases negative affective responses and maximizes rehabilitation adherence. A high-quality social support system and autonomous motivation have been suggested as important factors for enhancing rehabilitation adherence and decreasing negative affective responses.Citation33,Citation34 We therefore suggest that information about how to create a supportive environment should be included in education modules for coaches, physiotherapists, and other practitioners working with injured athletes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HägglundMWaldénMEkstrandJInjuries among male and female elite football playersScand J Med Sci Sports200919681982718980604

- SalmanAFComparison of injuries between male and female handball players in junior and senior teamsSwed J Sci Res201414115

- TranaeusUJohnsonUEngströmBSkillgateEWernerSA psychological injury prevention group intervention in Swedish floorballKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc201523113414342024934929

- StambulovaNStephanYJärphagUAthletic retirement: a cross-national comparison of elite French and Swedish athletesPsychol Sport Exerc20078101118

- ParkSLavalleeDTodDAthletes’ career transitions out of sport: a systematic reviewInt Rev Sport Exerc Psychol201362253

- HaggerMSChatzisarantisNLDGriffinMThatcherJInjury representations, coping, emotions, and functional outcomes in athletes with sports-related injuries: a test of self-regulation theoryJ Appl Sport Psychol2005351123452374

- DrawerSFullerCWPropensity for osteoarthritis and lower limb joint pain in retired professional soccer playersBr J Sports Med200135640240811726474

- LohmanderLSEnglundPMDahlLLRoosEMThe long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritisAm J Sports Med200735101756176917761605

- Wiese-BjornstalDMPsychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: a consensus statementScand J Med Sci Sports201020suppl 2103111

- ArdernCLTaylorNFFellerJAWebsterKEA systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injuryBr J Sports Med201347171120112623064083

- ForsdykeDSmithAJonesMGledhillAPsychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: a mixed studies systematic reviewBr J Sports Med201650953754426887414

- ArdernCKvistJWebsterKEPsychological aspects of anterior cruciate ligament injuriesOper Tech Sports Med20162417783

- BrewerBWThe role of psychological factors in sport injury rehabilitation outcomesInt Rev Sport Exerc Psychol201034061

- PodlogLHeilJSchulteSPsychosocial factors in sports injury rehabilitation and return to playPhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am201425491593025442166

- Hamson-UtleyJJVazquezLThe comeback: rehabilitating the psychological injuryAthlet Ther Today20081353538

- HerediaRASMunoxARArtazaJLThe effect of psychological response on recovery of sport injuryRes Sports Med20041211531

- BorensteinMHedgesLHigginsJComprehensive Meta AnalysisEnglewoodBiostat2009

- CardNAApplied Meta-Analysis for SocialScience ResearchNew York, NYGuilford Press2011

- MuthénLMuthénBMplus User’s Guide6Los Angeles, CAMuthén & Muthén1998

- ViswesvaranCOnesDSTheory testing: combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modelingPers Psychol1995484865885

- BaumanJReturning to play: the mind does matterClin J Sport Med200515643243516278547

- GouinJ-PKiecolt-GlaserJKThe impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and mechanismsImmunol Allergy Clin North Am2011311819321094925

- WalburnJVedharaKHankinsMRixonLWeinmanJPsychological stress and wound healing in humans: a systematic review and metaanalysisJ Psychosom Res200967325327119686881

- LupienSJMcEwenBSGunnarMRHeimCEffects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behavior and cognitionNat Rev Neurosci200910643444519401723

- PodlogLWBanhamSMWadeyRHannonJPsychological readiness to return to competitive sport following injury: a qualitative studySport Psychol2015291114

- BizziniMHancockDImpellizzeriFSuggestions from the field for return to sports participation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: soccerJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201242430431222467065

- BaumeisterRFDeWallCNVohsKDAlquistJLDoes emotion cause behavior (apart from making people do stupid, destructive things)?AgnewCRCarlstonDEGrazianoWGKellyJRThen a Miracle Occurs: Focusing on Behavior in Social Psychological Theory and ResearchNew York, NYOxford2010119136

- ValentineJCPigottTDRothsteinHRHow many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysisJ Educ Behav Stat2010352215247

- GohJXHallJARosenthalRMini meta-analysis of your own studies: some arguments on why and a primer on howSoc Pers Psychol Compass201610535549

- RaykovTLeeC-LMarcoulidesGAA commentary on the relationship between model fit and saturated path models in structural equation modeling applicationsEduc PsycholMeas201373610541068

- CupalDBrewerBEffects of relaxation and guided imagery on knee strength, re-injury anxiety, and pain following anterior cruciate ligament reconstructionRehabilPsychol2001462843

- JohnsonUShort-term psychological intervention: a study of long-term-injured competitive athletesJSport Rehabil20009207218

- ChanDKLonsdaleCHoPYYungPSChanKMPatient motivation and adherence to postsurgery rehabilitation exercise recommendations: the influence of physiotherapists′ autonomy-supportive behaviorsArch Phys Med Rehabil200990121977198219969157

- JohnsonUIvarssonAKarlssonJHägglundMWaldénMBärjessonMRehabilitation after first-time anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction in female football players: a study of resilience factorsBMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil201682027429759

- BrewerBWVan RaalteJLCorneliusAEPsychological factors, rehabilitation adherence, and rehabilitation outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstructionRehabil Psychol20004512037

- LentzTAZeppieriGJrGeorgeSZComparison of physical impairment, functional, and psychosocial measures based on fear of reinjury/lack of confidence and return-to-sport status after ACL reconstructionAm J Sports Med201543234535325480833

- LuFJHsuYInjured athletes’ rehabilitation beliefs and subjective well-being: the contribution of hope and social supportJ Athl Train2013481929823672330

- MüllerUKrüger-FrankeMSchmidtMRosemeyerBPredictive parameters for return to pre-injury level of sport 6 months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgeryKnee Surg Sports TraumatolAdthrosc2015231236233631

- PodlogLGaoZKenowLInjury rehabilitation overadherence: preliminary scale validation and relationships with athletic identity and self-presentation concernsJ Athl Train201348337238123675797

- ShinJTParkRSongWIKimSHKwonSMThe redevelopment and validation of the rehabilitation adherence questionnaire for injured athletesInt J Rehabil Res2010331647119809338