Abstract

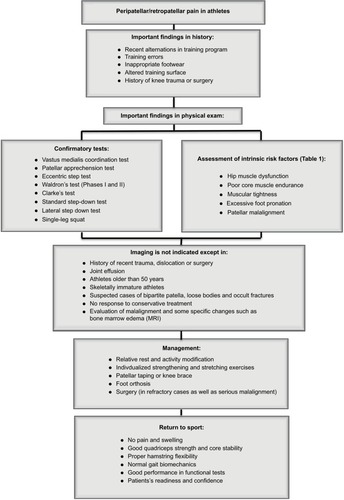

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a very common problem in athletes who participate in jumping, cutting and pivoting sports. Several risk factors may play a part in the pathogenesis of PFP. Overuse, trauma and intrinsic risk factors are particularly important among athletes. Physical examination has a key role in PFP diagnosis. Furthermore, common risk factors should be investigated, such as hip muscle dysfunction, poor core muscle endurance, muscular tightness, excessive foot pronation and patellar malalignment. Imaging is seldom needed in special cases. Many possible interventions are recommended for PFP management. Due to the multifactorial nature of PFP, the clinical approach should be individualized, and the contribution of different factors should be considered and managed accordingly. In most cases, activity modification and rehabilitation should be tried before any surgical interventions.

Introduction

Pain in retropatellar and peripatellar regions is clinically referred to as patellofemoral pain (PFP). However, there is not a clear definition. The term patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is still a “wastebasket”, which includes different entities.Citation1 It is a very common complaint in general population, particularly in young adult and adolescent athletes who participate in jumping, cutting and pivoting sports.Citation2–Citation4 It is reported that almost 25%–30% of all injuries seen in a sports medicine clinicCitation5,Citation6 and up to 40% of clinical visits for knee problemsCitation4,Citation7,Citation8 are attributed to PFP. PFP accounts for 33% and 18% of all knee injuries in female and male athletes, respectively.Citation9,Citation10 It is also one of the most common overuse injuries among different sports disciplines such as basketball,Citation11,Citation12 volleyballCitation13,Citation14 and running,Citation14–Citation17 and a prevalence rate of between 13% and 26% is reported in females participating in soccer, volleyball, running, fencing and rock climbing.Citation14 Incidence of PFP among adolescent females and young adult women is 2–10 times more than in their male counterparts.Citation10,Citation17,Citation18 PFP symptoms may lead to limitation of sport and physical activities in 74% of patients or cause sports cessation.Citation19–Citation21

Current literature contradicts the hypothesis that PFP has a benign and self-limiting course; in contrast, PFP is a refractory condition which may persist for many years and is a likely contributor to long-term patellofemoral osteoarthritis, especially in cases of adolescent anterior knee pain.Citation21–Citation24 Otherwise, some young PFP patients may have risk factors that place them at future risk for anterior cruciate ligament injury.Citation25

Terminology

Despite different terms proposed to describe this condition, such as anterior knee pain or syndrome, PFP, patellofemoral pain syndrome, patellofemoral arthralgia, chondromalacia patellae, lateral patellar compression syndrome and patellalgia,Citation26 a recent consensus statement from the Fourth International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat recommended PFP as the preferred term. However, it does not consider how nonpainful joint conditions could be a precursor to pain development and does not include symptoms such as crepitus, and its main focus is on the “pain” aspect of the disorder.Citation27,Citation28

Definition

PFP is characterized by pain in the peripatellar/retropatellar area that aggravates with at least one activity that loads the patellofemoral joint during weight bearing on a flexed knee (e.g., squatting, stair climbing, jogging/running and hopping/jumping). Additional nonessential criteria include crepitus or grinding sensation in the patellofemoral joint during knee flexion movements, tenderness on patellar facet palpation, small effusion and pain on sitting, rising on sitting or straightening the knee following sitting.Citation27–Citation29

Risk factors

As an overuse injury, several risk factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of PFP. These risk factors are classified as intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors.Citation3

Extrinsic risk factors are related to factors outside the body, such as the type and volume of sports activity, environmental conditions and the surface and equipment used. Intrinsic risk factors are attributed to individual characteristics.Citation3

Expert consensus statements suggest biomechanical risk factors explained by anatomic location relative to the knee. These factors include proximal (upper femur, hip and trunk), local (in and around the patella and the patellofemoral joint) and distal (lower leg, foot and ankle).Citation6,Citation30,Citation31 These risk factors can be anatomic (increased femoral anteversion, trochlear dysplasia, patella alta and baja, excessive foot pronation and so on) or biomechanical (muscle tightness or weakness, generalized joint laxity, gait abnormalities and so on).

Some of these proposed intrinsic risk factors and clinical tests for their assessment have been shown in .

Table 1 Potential intrinsic risk factors, tests for assessment and their reliability

History

Patients with PFP typically describe diffuse ill-defined pain behind, underneath or around the patella, usually with activities such as squatting, running and stair ascent or descent.Citation32,Citation34,Citation100 If asked to point to the site of pain, patients may place their hands over the anterior aspect of the knee or draw a circle with their fingers around the patella (the circle sign). The symptoms are usually of gradual onset, although some of them may be acute and caused by trauma. Pain may be unilateral or bilateral and is usually described as achy, but may be sharp.Citation32,Citation34 Sometimes, patients report stiffness or pain on prolonged sitting with the flexed knees (the theater or moviegoer sign).Citation34

Patients may occasionally report the knee giving way or buckling. This perceived instability may be due to inhibitory effect of pain on the suitable contraction of the quadriceps, but it should be differentiated from instability originating from a patellar dislocation, subluxation or ligamentous injury of the knee.Citation32,Citation101 Feeling of a popping or catching may be described. Locking of the joint is not characteristic of PFP and implies a meniscal tear or loose body. Occasionally, mild swelling may be present. However, it is rare to see a gross effusion seen with a traumatic knee injury.Citation32,Citation34

Taking history in athletes presenting with PFP may mandate some special considerations. As PFP is attributed to overuse in many cases, recent alterations in sporting activities, including any changes in the frequency, duration and intensity of training should be investigated in detail.Citation34,Citation100 The training program also should be appraised for errors, including increasing the exercise intensity too rapidly, inadequate recovery time and extreme hill workouts.Citation32 It must be considered that PFP may present as an acute re-exacerbation of the chronic condition.Citation100

Use of inappropriate or excessively worn footwear, recent heavy resistance training and conditioning activities (particularly squats and lunges) and running on altered surface or hills should also be considered. A history of knee traumatic injuries, including patellar subluxation or dislocation, or surgeries should be noted, as they may directly damage the articular cartilage or change the forces across the patellofemoral joint, resulting in PFP.Citation32,Citation34

Physical examination

Physical examination is the foundation of PFP diagnosis,Citation102 but there is no definitive clinical test to diagnose PFP.Citation103 A variety of tests have been explained to diagnose PFP.Citation104,Citation105 However, the common tests for PFP are not sensitive when compared with pathologic operative findings.Citation104 Lack of sensitive tests to help rule out PFPS when negative implies that PFPS may be a diagnosis of exclusion and may be best identified after ruling out other diagnoses such as tibiofemoral osteoarthritis, plica syndrome or other masquerading conditions.Citation106 According to the recent consensus statement from the Fourth International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, anterior knee pain elicited during a squatting maneuver is the best available test, and PFP is evident in 80% of people who are positive on this test.Citation103 Several other tests proposed for PFP have limited evidence supporting their use. Tenderness on palpation of the patellar edges is another test with limited evidence and PFP is evident in 71%–75% of people with this finding.Citation103 Full range of knee motion and lack of effusion are common findings in PFP patients.Citation28,Citation103 Patellar grinding and inhibition tests (e.g., Clarke’s test) have low sensitivity and limited diagnostic accuracy for PFP.Citation103

In another prospective study on the diagnostic value of five common tests, the authors reported three tests of vastus medialis coordination, patellar apprehension and eccentric step to have a positive ratio. It means that positive test results increase the likelihood of PFP.Citation80,Citation105 As an important point, clinical examination of athletes engaging in high-demanding sports may necessitate more challenging and highly dynamic tests (e.g., single leg-squat or lateral step-down tests) to reveal the subtle cases of overuse injuries.

In this part, we will describe the common clinical tests used for PFP diagnosis.

Vastus medialis coordination test

In patient’s supine position, the examiner places the fist under the subject’s knee and asks the patient to extend the knee slowly without pressing down or lifting away from the examiner’s fist. The patient is instructed to achieve full extension (). The test is considered positive when a lack of coordinated full extension is apparent, that is, when the patient either has difficulty smoothly achieving extension or uses the extensors or flexors of the hip to accomplish extension. A positive test may be an indicator of dysfunction of the vastus medialis obliquus muscle.Citation105,Citation107

Patellar apprehension test

The patellar apprehension test, also referred to as the Fairbanks apprehension test, is performed with the patient in supine and relaxed position. The examiner uses one hand to push the patient’s patella as lateral as possible, in order to obtain a lateral patellar glide. Starting with the knee flexed at 30°, the examiner grasps the leg at the ankle/heel with the other hand and performs a slow, combined flexion in the knee and hip. This lateral glide is maintained throughout the test (). The test is considered positive when it reproduces the patient’s pain or when apprehension is present.Citation104,Citation105,Citation107

Eccentric step test

For the eccentric step test, the patients perform the testing in bare feet. The step is 15 cm high or more accurately with height equal to 50% of the length of tibia. Briefly, each patient is asked to stand on the step, put hands on the hips and step down from the step as slowly and smoothly as she/he can. Patients should keep the hands on their hips throughout the test performance (). After the patient performs the test with one leg, the procedure is repeated using the other leg. A warm-up or practice attempt is not allowed. The eccentric step test is considered positive when the patient reports knee pain during the test performance.Citation105,Citation108,Citation109

Waldron’s test (Phases I and II)

To do Phase I of Waldron’s test, patient lies supine and the examiner presses the patella against the femur while concurrently performing a passive knee flexion with the other hand ().Citation110 For Phase II, the standing patient performs a slow, full squat, again with the examiner performing a gentle compression of the patella against the femur (). In both phases, crepitus and pain during a particular part of the range of motion are considered signs of PFP disorders.Citation105,Citation107

Clarke’s test (or patellofemoral grinding test)

Clarke’s test is performed with the patient lying supine with both knees supported by a pad, in order to create an adequate amount of knee flexion (10°–20°) and consequent articulation of the patella in the patellofemoral joint.Citation107 While the patient is relaxed, the examiner presses the patella distally (with the hand on the superior border of the patella) and then requests the patient to contract the quadriceps muscle ().Citation104 If the patient’s pain is reproduced during the test, the test will be considered positive. However, as explained before, Clarke’s test is not recommended as a diagnostic test for PFP due to the lack of clarity regarding its definite mechanics of application, uncertainty regarding what represents a positive test and its poor diagnostic accuracy.Citation26

Standard step-down test

Standard step-down test is very similar to eccentric step test, except that the patient should stand with arms folded across the chest and be instructed to squat down 5–10 times consecutively in a slow and controlled manner until the heel touches the floor, maintaining their balance at a rate of approximately one squat per 2 s (). Scoring of the deviations in the trunk, pelvis, hip and knee reveals the onset timing of the anterior gluteus medius, hip abduction torque and decreased lateral trunk strength.Citation100 Excellent inter-rater (k=0.80) and intra-rater (k=0.80) reliability has been reported for this test.Citation111

Lateral step-down test

The lateral step-down test is a modification of standard step-down test, in which the movement is in the lateral direction.Citation112 Instructions for the lateral step-down test are as follows: The patient is requested to stand with the involved leg on a 15 cm step. This will require most to bend the knee at about 60° during the test. The patient is asked to reach down and touch the opposite, non-involved heel to the ground, then return to the starting position. The patient should be rated on the criteria, including arm strategy, trunk alignment, pelvis plane, knee posture and steadiness.Citation100

Single-leg squat

Single-leg squat is a test of dynamic hip and quadriceps strength in the examination. This maneuver imposes higher mechanical demands than a bilateral squat, which may induce compensatory movements such as knee valgus (). This may partially be due to the smaller base of support and increased amounts of dynamic control that are needed in all planes during the single limb squat. Compared to controls, patients with PFP showed increased ipsilateral trunk lean, contralateral pelvic drop, hip adduction and knee abduction during a single-leg squat.Citation100,Citation113

As noted earlier, assessment of common intrinsic risk factors of PFP is crucial in physical examination and for planning proper rehabilitation program (). An illustrated description of the simple clinical methods to assess these common risk factors has been published.Citation114

Imaging

The diagnosis of PFPS is mainly clinical, and diagnostic imaging is not required for many patients. However, plain radiography may be indicated in the following cases: a history of recent trauma, dislocation or surgery, joint effusion, patients older than 50 years (to assess for patellofemoral osteoarthritis), patients who are skeletally immature (to rule out other causes such as osteochondritis dissecans, physeal injury or bone tumors), suspected cases of bipartite patella, loose bodies and occult fractures, and those who do not demonstrate improvement after several weeks of conservative treatment. Radiography is an adjunct to history and physical examination.Citation32,Citation34 Nevertheless, radiographic findings may not correlate well with clinical complaints, and often, the symptomatic side is difficult to differentiate from the asymptomatic side.Citation80

The diagnosis of PFPS depends primarily on the history and physical exam, but radiography is an adjunct to them. It is essential to obtain radiographs in the athlete who has apparent PFP and does not reveal improvement after several weeks of conservative treatment, or if there has been a severe malalignment or history of recent trauma.Citation32 The standard radiographic series for assessment of patellofemoral problems includes weight-bearing anterior-posterior (A–P), weight-bearing lateral, and axial or Merchant views in 20°–45° of knee flexion.Citation32,Citation115

Standard A–P radiograph is useful to identify accessory ossification centers, degenerative joint disease and bone tumors.Citation32 The lateral view is most valuable for the assessment of patellar height.

Axial views allow evaluation of degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint, osteochondritis dissecans of the patella, patellar morphology, dysplasia of the trochlear groove, and accessory ossification centers and ectopic calcifications in the retinaculum.Citation32 However, some studies recommend straight lateral projection X-ray for evaluation of the trochlear configuration and subtle patellar tracking abnormalities.Citation116 Where osteoarthritis seems to dominate in the patellofemoral compartment, the radiographic features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis include joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts and osteophytes at the posterior margins of the patella.Citation115

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not needed for most patients with PFP. MRI is the best tool for evaluation of malalignment, trochlear dysplasia, patella tilt and articular chondral injuries.Citation94,Citation117,Citation118 MRI can be useful in detecting, loose bodies, patellar stress fractures and bone marrow edema, which is suggestive of patellar subluxation or dislocation.Citation34 Cartilage loss and subchondral sclerosis, edema and cystic changes at the patellar and trochlea surfaces are the main findings in patellofemoral osteoarthritis on MRI.Citation115

Differential diagnosis

A systematic knee and hip examination is necessary, particularly in children and adolescents, to rule out other causes of anterior knee pain. Anteromedial knee pain, particularly in adolescents, can be a consequence of plica syndrome.Citation119 Pain localized to the inferior patellar pole may suggest patellar tendinopathy in adults engaged in jumping sports or Sinding Larsen Johansson disease in children. A history of acute knee trauma and joint effusion frequently identifies ligament injuries, patellar dislocations or meniscal tears. Tenderness and swelling around the tibial tuberosity in adolescents indicate Osgood-Schlatter disease. Sensations of the patellar movement or popping out may suggest patellar instability or subluxation, mainly during rotational activities.

Prolonged morning stiffness (>30 min), simultaneous involvement of several joints or tendons and joint swelling may be a presentation of systemic rheumatologic joint disease.Citation102

Management

Despite the high prevalence, chronicity and burden, PFP continues to be one of the most difficult musculoskeletal conditions managed by medical professionals.Citation120 It is evident that greater pain severity and longer symptom duration are indicators of poor prognosis. So, early efficient intervention may be crucial to limit the long-term effects of the condition.Citation121

Many possible interventions are recommended by sports medicine practitioners for athletes with PFP; however, no well-established guidelines exist for management of the symptoms.Citation122

Due to the multifactorial nature of PFP, the clinical approach should be individualized, and the contribution of different risk factors, including local, proximal (trunk and hip) and distal (foot) factors, should be considered and managed accordingly.Citation121,Citation123 This approach may add to the treatment effects on pain and function in patients.Citation123 The physicians can use patient education leaflet during management.Citation124

There is general agreement that nonsurgical interventions are the primary choice for PFP treatment. However, in order to select sound choices for the best management, practitioners need up-to-date, high-quality evidence.Citation121

In this part, we aim to discuss about the most common interventions, according to the existing evidence.

Relative rest and activity modification

In athletes in whom overuse may play a more significant role, the impact of rest will be more evident. In an acute injury, relative rest will permit the tissue to heal and the symptoms will diminish. In more chronic cases, the physiologic responses may cause daily activities to surpass the pain threshold. This situation leads to a considerable clinical challenge and needs sound patient education to avoid painful joint loading.Citation125

Exercise

There is consistent evidence that exercise therapy for PFP may result in clinically important reduction of pain in the short, medium and long terms; improvement in functional ability in the medium and long terms, as well as enhancing long-term recovery.Citation126 Also, it has been shown to be cost-effective and is the treatment of choice, especially in young adults.Citation127 However, the best mode of exercise therapy is unknown.Citation128

There is inadequate information to compare the relative effects of exercise versus other conservative interventions, either unimodal (e.g., taping) or multimodal (combinations of interventions that may include different exercises).Citation128

The low-quality existing evidence for comparisons of various exercises is not enough to draw conclusions on the relative results of supervised versus home-based exercises, open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, high- versus low-intensity exercises, hip versus knee exercises, and different variants of closed chain exercises and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching and aerobic exercise versus classic stretching and quadriceps exercises. Combining hip and knee exercises is more successful to reduce pain and improve function in the short, medium and long terms, and this combination should be used in preference to knee exercises alone.Citation126

There is a lack of high-quality evidence on the exercise medium (land versus water) and the duration of exercises.Citation128

Nowadays, considerable debate exists on the specific exercises, target muscles and duration of an ideal exercise program for patients with PFP.Citation129 Both strengthening and stretching exercises are recommended in exercise therapy. Nonetheless, assessment of individual risk factors may determine the proper combination of different exercises.Citation123

Strengthening

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that positive results were apparent with strengthening exercises, particularly knee extension, squats, stationary cycling, static quadriceps, active straight-leg raise, leg press and step-up and step-down exercises. The current evidence supports a prescription of daily exercises of two to four sets of ≥10 repetitions over a period of ≥6 weeks.Citation130

A systematic review of conservative interventions for PFP from 2000 to 2010 deduced that both weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing quadriceps-strengthening exercises are useful for pain reduction.Citation131 Although practitioners may prefer weight-bearing exercises to increase the functional activity, the use of non-weight-bearing exercise may be equally valuable, mostly for patients with noticeable quadriceps weakness. One important factor emphasized in recent reviews is that exercises should be pain free,Citation131 and applying heavy resistance to the quadriceps will likely perpetuate or aggravate the condition.Citation132

Considering the biomechanical stresses at the patellofemoral joint during exercise, it is better to prescribe non-weight-bearing and weight-bearing exercises at 90°–45° and 45°–0° of knee flexion, respectively.Citation125

Strengthening program should focus particularly on the vastus medialis oblique, hip abductors and external rotators, as well as core stability training.Citation132,Citation133

Although hip exercises have been recommended for the strengthening purpose (i.e., three sets of 10–15 repetitions), there is an indication that muscle endurance also needs to be increased. So, practitioners should consider higher repetitions of sets (i.e., three sets of 20–30 repetitions), in particular, for PFP patients who are involved in more demanding sports such as running and jumping.Citation125

Stretching

Stretching of the hamstring, quadriceps, iliopsoas, gastrocnemius and iliotibial band muscles has been studied for PFP. Theoretically, tight hamstrings, gastrocnemius or iliotibial band muscles may increase the patellofemoral joint reaction forces in full knee extension, whereas tight quadriceps or iliopsoas could cause the same in full flexion.Citation134 Lower extremity stretching alone or combined with strengthening exercises or other interventions may improve PFP symptoms in up to 60% of patients.Citation120,Citation122 Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching techniques such as contract–relax may be more effective than traditional static or ballistic stretching exercises.Citation135 Stretching exercises are recommended as a part of the conservative management of PFP.Citation125

In the case of hamstring tightness, patients are trained to perform three alternating repetitions of four passive stretching exercises, and all stretching repetitions will be held for 15 s (12×15 s). This program will continue until the end of the 12-week program.Citation136 In patients with hip flexor tightness, the stretching comprises passive modified lunge stretches and active prone leg lifts with the knee bent. Both stretches are done for 10 repetitions each in a single daily session and each stretch held for 30 s, with up to a 30-s rest period between repetitions.Citation114,Citation137 To address iliotibial band, common standing stretches in three positions of upright standing, overhead clasped hands and diagonally lowered arms are performed.Citation114,Citation138 In the case of gastrocnemius tightness, static stretching in forward lunge position is advised. Patients are taught to hold the static stretch for 60 s and complete two repetitions, for a total of 120 s of stretch during each session. Each session is performed on a daily basis over a 12-week period.Citation114,Citation139,Citation140

Patellar taping

Recent systematic reviews have represented conflicting conclusions regarding the use of patellar taping for PFP. A meta-analysis by Warden et al concluded that a clinically significant reduction in chronic knee pain happens with medially directed tape.Citation141 In contrast, a 2012 Cochrane review showed that there was no statistically or clinically significant difference in pain scores on comparing taping with no taping at the end of the treatment period.Citation142 Another study demonstrated that taping has minimal effect in management of long-term PFP symptoms; however, clinicians may use patellar taping as a short-term intervention to allow patients to perform pain-free exercise.Citation131

A systematic review by Barton et al. concluded that tailored patellar taping immediately reduces pain with a large effect, while other techniques have only small (untailored medial patellar taping) or negligible (Kinesio Tape) effects on pain in the immediate term. The authors recommend patellar taping to control lateral patellar tilt, translation and spin, with the goal of providing at least 50% pain reduction. The proposed mechanisms for effectiveness of patellar taping include facilitation of earlier vastus medialis oblique onset and enhanced knee function capability during functional tasks.Citation143 There is minimal evidence that taping significantly adjusts patellar alignment; however, it may increase the patellofemoral contact area, leading to a decrease in pain.Citation125

Knee brace

Similar to taping, existing evidence has achieved conflicting conclusions about the outcomes of patellofemoral bracing. Overall, there is moderate evidence that knee braces have no additional benefit over exercise therapy on pain and function, and there is also moderate evidence for no significant difference in efficiency between knee braces and exercise therapy versus placebo knee braces and exercise therapy.Citation144 Nevertheless, some findings suggest that the Protonics knee brace may be an effective intervention for pain reduction. However, the exact mechanism for improvement is still unclear.Citation131 Another study showed that the use of a medially directed realignment brace may result in better outcomes in patients with PFP than exercise alone after 6 and 12 weeks of treatment, but this positive effect reduced after 1 year of follow-up.Citation145

A similar study also showed that patellar bracing may alleviate the symptoms of PFP.Citation146 Although the exact mechanisms of these positive outcomes are not obvious, they may be the result of redistributed patellar stress, increased proprioceptive input and improved neuromuscular control.Citation131 As a conclusion, patellar braces should only be used as an adjunct to other interventions; but to find a definitive answer to this clinical question, the heterogeneity of studies, the variety of braces and the quality of outcome assessment should be borne in mind.Citation125

Foot orthosis

There is inadequate and sometimes conflicting evidence regarding the prescription of foot orthosis as an effective intervention for PFP.Citation125,Citation144

A systematic review concluded that there is limited evidence for the use of prefabricated foot orthosis for short-term improvements in PFP. This review also reported that physiotherapy combined with prefabricated foot orthosis is more effective than foot orthosis alone.Citation147

According to the 2016 consensus statement from the Fourth International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, foot orthosis was recommended for short-term pain relief in patients with PFP.

However, it should be emphasized that the average pain reduction may be deemed to lack clinical significance, as a result of considerable individual variability in response.Citation148 The cardinal point is that foot orthosis may not be helpful for all patients with PFP, and identifying those most likely to benefit from foot orthosis is important. Published studies have described clinical characteristics that can be used to predict success with foot orthosis intervention, including greater midfoot mobility,Citation149 less ankle dorsiflexion and immediate improvements in PFP, when performing a single-leg squat with foot orthosis.Citation150

Physical modalities

Systematic reviews and RCTs have demonstrated a lack of supportive evidence for the use of physical agents such as therapeutic ultrasound, phonophoresis, iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, medium-frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation, low-level laser, extracorporeal shock-wave therapy, electromyographic biofeedback and massage therapies.Citation102,Citation125,Citation151,Citation152 There is little justification for using these modalities alone for PFP patients.Citation102,Citation126 However, despite the lack of clear evidence currently, cryotherapy is still recommended as a part of the conservative treatment for PFP.Citation125

Pharmacotherapy

Drugs commonly used for PFP include simple analgesics such as aspirin or acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A Cochrane review of drug therapy for PFP found no important differences in clinical symptoms comparing aspirin with placebo and limited evidence for the efficacy of NSAIDs for short-term pain reduction. Another Cochrane review showed that topical NSAIDs are as effective as oral NSAIDs for pain relief in chronic musculoskeletal pain.Citation153 However, NSAIDs may not be recommended due to the absence of a histologic inflammatory response in many PFP cases as well as existing concerns regarding their possible adverse effects on normal healing response of muscles and tendons. Short courses of NSAIDs may be helpful when other modalities such as exercise and analgesics have failed or pain control is necessary for performing the exercise program.Citation125

Surgery

Surgery is the last alternative for PFP and appears to be inadequate. This is emphasized by an RCT that showed no additional improvement in PFP symptoms and function over 9 months after surgery.Citation121 Open, arthroscopic and percutaneous techniques have been described as the surgical options. Surgery is usually reserved for refractory cases nonresponsive to conservative treatment. In cautiously selected patients, surgery may be successful, although failure rates of 20%–30% have been reported.Citation125 In some selected cases such as serious malalignment (femoral torsional deformity and so on), patella alta or lateral patellar compression syndrome, good outcomes were reported.Citation154–Citation156

Other therapies

Acupuncture and dry needling have been suggested as useful interventions for PFP. Limited evidence revealed a statistically significant pain reduction in the medium term following acupuncture.Citation125 Sclerotherapy and prolotherapy injections are among other proposed interventions, although no high-quality evidence exists for their use.Citation125 There is limited evidence that injection of Botulinum toxin type A to the distal region of vastus lateralis muscle may increase the activation of vastus medialis.Citation157 Patellofemoral, knee and lumbar mobilization or manipulation has been proposed as alternatives, but are not recommended according to the current evidence.Citation126

Multimodal approach

According to the recent literature on PFPS and its specific treatment recommendations, multimodal approach is highly recommended to reduce pain in athletes with PFP in the short and medium terms.Citation126 Combined program is the most effective and strongly supported treatment for patients with PFP and includes strength training of weak muscles, stretching of tight muscles and adjunctive therapies such as taping, bracing and foot orthosis, if applicable.Citation122 Sports medicine practitioners should particularly assess local, proximal and distal risk factors and use individualized multimodal approach.Citation121,Citation132 The algorithmic approach is summarized in .

Prognosis

A substantial proportion of individuals with PFP have an unfavorable recovery over 12 months, irrespective of the intervention. Duration of PFP >2 months is the most consistent predictor of poor long-term prognosis, along with a score of <70 on the anterior knee pain scale. Those who report higher levels of usual/resting or worst/activity-related pain should also be flagged as potentially having a poor 12-month prognosis. Sports medicine practitioners should promote education regarding the natural history and importance of early intervention for PFP, and prescribe interventions with known efficacy in reducing PFP, in order to maximize the prognosis.Citation158

Return to sport

Athletes may be concerned regarding the time of their return to sport. It is especially true for elite athletes who may plan to participate in important sport events. However, sports medicine practitioners should follow the objective criteria to clear the athletes for participation in sports. The athlete can return to sport when the following criteria are met:

No swelling

No pain in squatting and in ascending or descending stairs • Good quadriceps strength (especially vastus medialis obliques)

Proper hamstring flexibility

Normal gait biomechanics

Proper core stability strength

Good performance in challenging functional tests (vertical jumping, anteromedial lunge, step-down, single-leg press, and balance and reach tests)

The patient feeling that he/she is ready and has confidence in the injured kneeCitation3,Citation125,Citation159

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Reza Mazaheri and Dr Aabolfazl Hashempour for their assistance in preparation of the photos. Consent has been obtained for the patient photos to be used in this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WitvrouwEWernerSMikkelsenCVan TiggelenDVanden BergheLCerulliGClinical classification of patellofemoral pain syndrome: guidelines for non-operative treatmentKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc200513212213015703965

- LoudonJKGajewskiBGoist-FoleyHLLoudonKLThe effectiveness of exercise in treating patellofemoral-pain syndromeJ Sport Rehabil2004134323342

- WitvrouwELysensRBellemansJCambierDVanderstraetenGIntrinsic risk factors for the development of anterior knee pain in an athletic population. A two-year prospective studyAm J Sports Med200028448048910921638

- KannusPAhoHJärvinenMNttymäkiSComputerized recording of visits to an outpatient sports clinicAm J Sports Med198715179853812865

- DevereauxMDLachmannSMPatello-femoral arthralgia in athletes attending a sports injury clinicBr J Sports Med198418118216722419

- WitvrouwECallaghanMJStefanikJJPatellofemoral pain: consensus statement from the 3rd International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013Br J Sports Med201448641141424569145

- NatriAKannusPJärvinenMWhich factors predict the long-term outcome in chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome? A 7-yr prospective follow-up studyMed Sci Sports Exerc19983011157215779813868

- BaquiePBruknerPInjuries presenting to an Australian sports medicine centre: a 12-month studyClin J Sport Med19977128319117522

- LaBellaCPatellofemoral pain syndrome: evaluation and treatmentPrim Care2004314977100315544830

- DeHavenKELintnerDMAthletic injuries: comparison by age, sport, and genderAm J Sports Med19861432182243752362

- CumpsEVerhagenEMeeusenRProspective epidemiological study of basketball injuries during one competitive season: ankle sprains and overuse knee injuriesJ Sports Sci Med20076220421124149330

- LeppänenMPasanenKKujalaUMParkkariJOveruse injuries in youth basketball and floorballOpen Access J Sports Med2015617317926045679

- BrinerWWKacmarLCommon injuries in volleyballSports Med199724165719257411

- NejatiPForoghBMoeineddinRBaradaranHRNejatiMPatellofemoral pain syndrome in Iranian female athletesActa Med Iran201149316921681705

- van MechelenWRunning injuriesSports Med19921453203351439399

- van GentBRSiemDDvan MiddelkoopMvan OsTABierma-ZeinstraSSKoesBBIncidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic reviewBr J Sports Med2007418469480 discussion 48017473005

- TauntonJERyanMBClementDMcKenzieDCLloyd-SmithDZumboBA retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuriesBr J Sports Med20023629510111916889

- FulkersonJPDiagnosis and treatment of patients with patellofemoral painAm J Sports Med200230344745612016090

- FairbankJPynsentPvan PoortvlietJAPhillipsHMechanical factors in the incidence of knee pain in adolescents and young adultsBone Joint J1984665685693

- BlondLHansenLPatellofemoral pain syndrome in athletes: a 5.7-year retrospective follow-up study of 250 athletesActa Orthop Belg19986443934009922542

- NimonGMurrayDSandowMGoodfellowJNatural history of anterior knee pain: a 14-to 20-year follow-up of nonoperative managementJ Pediatr Orthop19981811181229449112

- MyerGDFordKRBarber FossKDThe incidence and potential pathomechanics of patellofemoral pain in female athletesClin Biomech (Bristol, Avon)2010257700707

- UttingMDaviesGNewmanJIs anterior knee pain a predisposing factor to patellofemoral osteoarthritis?Knee200512536236516146626

- ConchieHClarkDMetcalfeAEldridgeJWhitehouseMAdolescent knee pain and patellar dislocations are associated with patellofemoral osteoarthritis in adulthood: a case control studyKnee201623470871127180253

- MyerGDFordKRDi StasiSLFossKDBMicheliLJHewettTEHigh knee abduction moments are common risk factors for patellofemoral pain (PFP) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in girls: is PFP itself a predictor for subsequent ACL injury?Br J Sports Med201549211812224687011

- DobersteinSTRomeynRLReinekeDMThe diagnostic value of the Clarke sign in assessing chondromalacia patellaJ Athl Train200843219019618345345

- ThomeeRAugustssonJKarlssonJPatellofemoral pain syndrome: a review of current issuesSports Med199928424526210565551

- CrossleyKMStefanikJJSelfeJ2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 1: terminology, definitions, clinical examination, natural history, patellofemoral osteoarthritis and patient-reported outcome measuresBr J Sports Med2016501483984327343241

- PowersCMRehabilitation of patellofemoral joint disorders: a critical reviewJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther19982853453549809282

- DavisISPowersCMPatellofemoral pain syndrome: proximal, distal, and local factors, an international retreat, April 30–May 2, 2009, Fells Point, Baltimore, MDJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2010403A1A16

- PowersCMBolglaLACallaghanMJCollinsNSheehanFTPatellofemoral Pain: Proximal, Distal, and Local Factors—2nd International Research RetreatAugust 31–September 2, 2011Ghent, BelgiumJOSPT, Inc. JOSPT1033 North Fairfax Street, Suite 304, Alexandria, VA2213415402012

- ColladoHFredericsonMPatellofemoral pain syndromeClin Sports Med201029337939820610028

- HartHAcklandDPandyMCrossleyKQuadriceps volumes are reduced in people with patellofemoral joint osteoarthritisOsteoarthritis Cartilage201220886386822525223

- DixitSDiFioriJPBurtonMMinesBManagement of patellofemoral pain syndromeAm Fam Phys2007752194202

- LankhorstNEBierma-ZeinstraSMvan MiddelkoopMRisk factors for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic reviewJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2012422819422031622

- AgebergEZätterströmRMoritzUStabilometry and one-leg hop test have high test-retest reliabilityScand J Med Sci Sports1998841982029764440

- SteinkampLADillinghamMFMarkelMDHillJAKaufmanKRBiomechanical considerations in patellofemoral joint rehabilitationAm J Sports Med19932134384448346760

- RiceJBennettGRuhlingRComparison of two exercises on VMO and VL EMG activity and force productionIsokinet Exerc Sci1995526167

- InsallJCurrent concepts review: patellar painJ Bone Joint Surg19826411477033228

- RobinsonRLNeeRJAnalysis of hip strength in females seeking physical therapy treatment for unilateral patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200737523223817549951

- PrinsMRvan der WurffPFemales with patellofemoral pain syndrome have weak hip muscles: a systematic reviewAust J Physiother200955191519226237

- WilsonECore stability: assessment and functional strengthening of the hip abductorsStrength Condition J20052722123

- PresswoodLCroninJKeoghJWLWhatmanCGluteus medius: applied anatomy, dysfunction, assessment, and progressive strengtheningStrength Condition J200830541

- ReimanMPGoodeAPHegedusEJCookCEWrightAADiagnostic accuracy of clinical tests of the hip: a systematic review with meta-analysisBr J Sports Med2013471489390222773321

- EarlJEHochAZA Proximal strengthening program improves pain, function, and biomechanics in women with patellofemoral pain syndromeAm J Sport Med2011391154163

- FerberRBolglaLEarl-BoehmJEEmeryCHamstra-WrightKStrengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trialJ Athl Train201550436637725365133

- McGillSMChildsALiebensonCEndurance times for low back stabilization exercises: clinical targets for testing and training from a normal databaseArchiv Phys Med Rehabil1999808941944

- WaryaszGRMcDermottAYPatellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): a systematic review of anatomy and potential risk factorsDyn Med20087918582383

- WhiteLCDolphinPDixonJHamstring length in patellofemoral pain syndromePhysiotherapy2009951242819627682

- PivaSRGoodniteEAChildsJDStrength around the hip and flexibility of soft tissues in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2005351279380116848100

- DavisDSQuinnROWhitemanCTWilliamsJDYoungCRConcurrent validity of four clinical tests used to measure hamstring flexibilityJ Strength Cond Res200822258358818550977

- DavisDSAshbyPEMcCaleKLMcQuainJAWineJMThe effectiveness of 3 stretching techniques on hamstring flexibility using consistent stretching parametersJ Strength Cond Res2005191273215705041

- YoudasJWKrauseDAHollmanJHHarmsenWSLaskowskiEThe influence of gender and age on hamstring muscle length in healthy adultsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200535424625215901126

- FredriksenHDagfinrudHJacobsenVMaehlumSPassive knee extension test to measure hamstring muscle tightnessScand J Med Sci Sports1997752792829338945

- GabbeBBennellKWajswelnercHFinchCReliability of common lower extremity musculoskeletal screening testsPhys Ther Sport2004529097

- TylerTFNicholasSJMullaneyMJMcHughMPThe role of hip muscle function in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndromeAm J Sports Med200634463063616365375

- PostWRPatellofemoral pain: results of nonoperative treatmentClin Orthop Relat Res20054365559

- BartlettMDWolfLSShurtleffDBStahellLTHip flexion contractures: a comparison of measurement methodsArch Phys Med Rehabil19856696206254038029

- HarveyDAssessment of the flexibility of elite athletes using the modified Thomas testBr J Sports Med199832168709562169

- WinslowJYoderEPatellofemoral pain in female ballet dancers: correlation with iliotibial band tightness and tibial external rotationJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther199522118217550298

- PunielloMSIliotibial band tightness and medial patellar glide in patients with patellofemoral dysfunctionJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther19931731441488472078

- HudsonZDarthuyEIliotibial band tightness and patellofemoral pain syndrome: a case-control studyMan Ther200914214715118313972

- HerringtonLRivettNMunroaSThe relationship between patella position and length of the iliotibial band as assessed using Ober’s testMan Ther200611318218616867314

- WangTGJanMHLinKHWangHKAssessment of stretching of the iliotibial tract with Ober and modified Ober tests: an ultrasonographic studyArchiv Phys Med Rehabil2006871014071411

- MelchioneWESMReliability of measurements obtained by use of an instrument designed to indirectly measure iliotibial band lengthJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther19931835115158298633

- ReeseNBandyWUse of an inclinometer to measure flexibility of the iliotibial band using the Ober test and the modified Ober test: differences in magnitude and reliability of measurementsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200333632633012839207

- Sanchis-AlfonsoVRosello-SastreEMartinez-SanjuanVPathogenesis of anterior knee pain syndrome and functional patellofemoral instability in the active youngAm J Knee Surg1999121294010050691

- DennisRJFinchCFElliottcBCFarhartPJThe reliability of musculoskeletal screening tests used in cricketPhys Ther Sport200891253319083701

- BennellKLTalbotRCWajswelnerHTechovanichWKellyDHHallAJIntra-rater and inter-rater reliability of a weight-bearing lunge measure of ankle dorsiflexionAust J Physiother199844317518011676731

- BartonCJBonannoDLevingerPMenzHBFoot and ankle characteristics in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a case control and reliability studyJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201040528629620436240

- PowersCMMaffucciRHamptonSRearfoot posture in subjects with patellofemoral painJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther19952241551608535473

- BartonCJLevingerPCrossleyKMWebsterKEMenzHBRelationships between the Foot Posture Index and foot kinematics during gait in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Foot Ankle Res201141021401957

- RedmondACrosbieJOuvrierRDevelopment and validation of a novel rating system for scoring standing foot posture: the Foot Posture IndexClin Biomech (Bristol, Avon)20062118998

- RedmondACCraneYZMenzHBNormative values for the foot posture indexJ Foot Ankle Res200811618822155

- KannusPNiittymakiSWhich factors predict outcome in the nonoperative treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome? A prospective follow-up studyMed Sci Sports Exerc19942632892968183092

- BradyRJDeanJBSkinnerTMGrossMTLimb length inequality: clinical implications for assessment and interventionJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200333522123412774997

- GogiaPPBraatzJHValidity and reliability of leg length measurementsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther19868418518818802226

- HoyleDLatourMBohannonRIntraexaminer, interexaminer, and inter-device comparability of leg length measurements obtained with measuring tape and metrecomJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther199114626326818796809

- FredericsonMYoonKPhysical examination and patellofemoral pain syndromeAm J Phys Med Rehabil200685323424316505640

- HaimAYanivMDekelSAmirHPatellofemoral pain syndrome: validity of clinical and radiological featuresClin Orthop Relat Res200645122322816788411

- WatsonCJProppsMGaltWReddingADobbsDReliability of McConnell’s classification of patellar orientation in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjectsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther1999297378385 discussion 386–39310416177

- PowersCMMortensonSNishimotoDSimonDCriterion-related validity of a clinical measurement to determine the medial/lateral component of patellar orientationJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther199929737237710416176

- WatsonCJLeddyHMDynjanTDParhamJLReliability of the lateral pull test and tilt test to assess patellar alignment in subjects with symptomatic knees: student ratersJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200131736837411451307

- SmithTODaviesLDonellSTThe reliability and validity of assessing medio-lateral patellar position: a systematic reviewMan Ther200914435536218824392

- al-RawiZNessanAHJoint hypermobility in patients with chondromalacia patellaeBr J Rheumatol19973612132413279448595

- BoyleKLWittPRiegger-KrughCIntrarater and interrater reliability of the beighton and horan joint mobility indexJ Athl Train200338428128514737208

- Juul-KristensenBRogindHJensenDVRemvigLInter-examiner reproducibility of tests and criteria for generalized joint hypermobility and benign joint hypermobility syndromeRheumatology (Oxford)200746121835184118006569

- RemvigLJensenDVWardRCAre diagnostic criteria for general joint hypermobility and benign joint hypermobility syndrome based on reproducible and valid tests? A review of the literatureJ Rheumatol200734479880317295436

- LunVMeeuwisseWStergiouPStefanyshynDRelation between running injury and static lower limb alignment in recreational runnersBr J Sports Med200438557658015388542

- KrausVBVailTPWorrellTMcDanielGA comparative assessment of alignment angle of the knee by radiographic and physical examination methodsArthritis Rheumatol200552617301735

- MacriEMStefanikJJKhanKKCrossleyKMIs tibiofemoral or patellofemoral alignment or trochlear morphology associated with patellofemoral osteoarthritis? A systematic reviewArthritis Care Res2016681014531470

- DaviesAPCostaMLDonnellSTGlasgowMMShepstoneLThe sulcus angle and malalignment of the extensor mechanism of the kneeBone Joint J200082811621166

- SmithTCoganAPatelSShakokaniMTomsADonellSThe intra-and inter-rater reliability of X-ray radiological measurements for patellar instabilityKnee201320213313822727319

- DuranSCavusogluMKocadalOSakmanBAssociation between trochlear morphology and chondromalacia patella: an MRI studyClin Imaging20174171027723501

- BakerVBennellKStillmanBCowanSCrossleyKAbnormal knee joint position sense in individuals with patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Orthop Res200220220821411918299

- CallaghanMJWhat does proprioception testing tell us about patellofemoral pain?Man Ther2011161464720702131

- StillmanBCAn investigation of the clinical assessment of joint position sense [PhD thesis]The University of MelbourneAustralia2000

- ThijsYVan TiggelenDRoosenPDe ClercqDWitvrouwEA prospective study on gait-related intrinsic risk factors for patellofemoral painClin J Sport Med200717643744517993785

- De CockADe ClercqDWillemsTWitvrouwETemporal characteristics of foot roll-over during barefoot jogging: reference data for young adultsGait Posture200521443243915886133

- ManskeRCDaviesGJExamination of the patellofemoral jointInt J Sports Phys Ther201611683127904788

- PostWRCurrent concepts clinical evaluation of patients with patellofemoral disordersArthroscopy199915884185110564862

- CrossleyKMCallaghanMJvan LinschotenRPatellofemoral painBMJ2015351h393926537829

- NunesGSStapaitELKirstenMHde NoronhaMSantosGMClinical test for diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome: systematic review with meta-analysisPhys Ther Sport2013141545923232069

- MalangaGAAndrusSNadlerSFMcLeanJPhysical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic testsArch Phys Med Rehabil200384459260312690600

- NijsJVan GeelCVan der auweraCVan de VeldeBDiagnostic value of five clinical tests in patellofemoral pain syndromeMan Ther2006111697715950517

- CookCMabryLReimanMPHegedusEJBest tests/clinical findings for screening and diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic reviewPhysiotherapy20129829310022507358

- SouzaTThe kneeHydeTEGengenbachMSConservative Management of Sport InjuriesBaltimore, MDWilliams & Wilkins1997394395

- SelfeJHarperLPedersenIBreen-TurnerJWaringJFour outcome measures for patellofemoral joint problems. Part 1: development and validityPhysiotherapy20018710507515

- SelfeJHarperLPedersenIBreen-TurnerJWaringJFour outcome measures for patellofemoral joint problems: part 2. Reliability and clinical sensitivityPhysiotherapy20018710516522

- ReiderBThe kneeReiderBThe Orthopaedic Physical Examination2nd edPhiladelphia, PAElsevier Saunders2005201246

- CrossleyKMZhangW-JSchacheAGBryantACowanSMPerformance on the single-leg squat task indicates hip abductor muscle functionAm J Sports Med201139486687321335344

- RabinAKozolZMoranUEferganAGeffenYFinestoneASFactors associated with visually assessed quality of movement during a lateral step-down test among individuals with patellofemoral painJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2014441293794625347229

- NakagawaTHMoriyaETMacielCDSerraoFVTrunk, pelvis, hip, and knee kinematics, hip strength, and gluteal muscle activation during a single-leg squat in males and females with and without patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201242649150122402604

- HalabchiFMazaheriRSeif BarghiTPatellofemoral pain syndrome and modifiable intrinsic risk factors; How to assess and address?Asian J Sports Med2013428510023802050

- EliasDAWhiteLMImaging of patellofemoral disordersClin Radiol200459754355715208060

- GallandOWalchGDejourHCarretJPAn anatomical and radiological study of the femoropatellar articulationSurg Radiol Anat19901221191252396177

- SamimMSmitamanELawrenceDMoukaddamHMRI of anterior knee painSkeletal Radiol201443787589324473994

- TunaBKSemiz-OysuAPekarBBukteYHayirliogluAThe association of patellofemoral joint morphology with chondromalacia patella: a quantitative MRI analysisClin Imaging201438449549824651059

- SchindlerOS‘The Sneaky Plica’ revisited: morphology, pathophysiology and treatment of synovial plicae of the kneeKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc201422224726223381917

- CrossleyKBennellKGreenSMcConnellJA systematic review of physical interventions for patellofemoral pain syndromeClin J Sport Med200111210311011403109

- CollinsNJBissetLMCrossleyKMVicenzinoBEfficacy of nonsurgical interventions for anterior knee pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trialsSports Med2012421314922149696

- RixeJAGlickJEBradyJOlympiaRPA review of the management of patellofemoral pain syndromePhys Sports Med20134131928

- HalabchiFMazaheriRMansourniaMAHamediZAdditional effects of an individualized risk factor-based approach on pain and the function of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trialClin J Sport Med201525647848625654629

- BartonCJRathleffMS‘Managing my patellofemoral pain’: the creation of an education leaflet for patientsBMJ open sport & exercise medicine201621e000086

- HiemstraLAKerslakeSIrvingCAnterior knee pain in the athleteClin Sports Med201433343745924993409

- CrossleyKMvan MiddelkoopMCallaghanMJCollinsNJRathleffMSBartonCJ2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 2: recommended physical interventions (exercise, taping, bracing, foot orthoses and combined interventions)Br J Sports Med2016501484485227247098

- RouxLExercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome costs society less than usual careClin J Sport Med201121327527621532353

- Van Der HeijdenRALankhorstNEVan LinschotenRBierma-ZeinstraSMVan MiddelkoopMExercise for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome: an abridged version of Cochrane systematic reviewEur J Phys Rehabil Med201652111013326158920

- RothermichMAGlavianoNRLiJHartJMPatellofemoral pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment optionsClin Sports Med201534231332725818716

- HarvieDO’LearyTKumarSA systematic review of randomized controlled trials on exercise parameters in the treatment of patellofemoral pain: what works?J Multidiscip Healthc2011438339222135495

- BolglaLABolingMCAn update for the conservative management of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2010Int J Sports Phys Ther20116211212521713229

- FulkersonJA practical guide to understanding and treating patellofemoral painAm J Orthop (Belle Mead, NJ)201746210128437495

- ThomsonCKrouwelOKuismaRHebronCThe outcome of hip exercise in patellofemoral pain: a systematic reviewMan Ther20162613027428378

- Al-HakimWJaiswalPKKhanWJohnstoneDThe non-operative treatment of anterior knee painOpen Orthop J2012632032622896779

- MoyanoFRValenzaMMartinLMCaballeroYCGonzalez-JimenezEDemetGVEffectiveness of different exercises and stretching physiotherapy on pain and movement in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trialClin Rehabil201327540941723036842

- Sainz de BarandaPAyalaFChronic flexibility improvement after 12 week of stretching program utilizing the ACSM recommendations: hamstring flexibilityInt J Sports Med201031638939620309785

- WintersMVBlakeCGTrostJSPassive versus active stretching of hip flexor muscles in subjects with limited hip extension: a randomized clinical trialPhys Ther200484980080715330693

- FredericsonMWhiteJJMacmahonJMAndriacchiTPQuantitative analysis of the relative effectiveness of 3 iliotibial band stretchesArch Phys Med Rehabil200283558959211994795

- GajdosikRLAllredJDGabbertHLSonstengBAA stretching program increases the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties of the calf muscle-tendon unit of unconditioned younger womenEur J Appl Physiol200799444945417186300

- NakamuraMIkezoeTTakenoYIchihashiNEffects of a 4-week static stretch training program on passive stiffness of human gastrocnemius muscle-tendon unit in vivoEur J Appl Physiol201211272749275522124523

- WardenSJHinmanRSWatsonMAAvinKGBialocerkowskiAECrossleyKMPatellar taping and bracing for the treatment of chronic knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysisArthritis Care Res20085917383

- CallaghanMPatellar taping for patellofemoral pain syndrome in adults. Results from the Cochrane reviewJ Orthop Sports Phys2012426A53A54

- BartonCBalachandarVLackSMorrisseyDPatellar taping for patellofemoral pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate clinical outcomes and biomechanical mechanismsBr J Sports Med201448641742424311602

- SwartNMvan LinschotenRBierma-ZeinstraSMvan MiddelkoopMThe additional effect of orthotic devices on exercise therapy for patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic reviewBr J Sports Med201246857057721402565

- PetersenWEllermannARembitzkiIVEvaluating the potential synergistic benefit of a realignment brace on patients receiving exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trialArch Orthop Trauma Surg2016136797598227146819

- LunVMYWileyJPMeeuwisseWHYanagawaTLEffectiveness of patellar bracing for treatment of patellofemoral pain syndromeClin J Sport Med200515423524016003037

- BartonCJMunteanuSEMenzHBCrossleyKMThe efficacy of foot orthoses in the treatment of individuals with patellofemoral pain syndromeSports Med201040537739520433211

- CollinsNCrossleyKBellerEDarnellRMcPoilTVicenzinoBFoot orthoses and physiotherapy in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome: randomised clinical trialBMJ2008337a173518952682

- VicenzinoBCollinsNClelandJMcPoilTA clinical prediction rule for identifying patients with patellofemoral pain who are likely to benefit from foot orthoses: a preliminary determinationBr J Sports Med2010441286286618819958

- BartonCJMenzHBCrossleyKMClinical predictors of foot orthoses efficacy in individuals with patellofemoral painMed Sci Sports Exerc20114391603161021311359

- LakeDAWoffordNHEffect of therapeutic modalities on patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic reviewSports Health20113218218923016007

- Dos SantosRLSouzaMLDos SantosFANeuromuscular electric stimulation in patellofemoral dysfunction: literature reviewActa Ortop Bras2013211525824453645

- DerrySMooreRARabbieRTopical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20129CD00740022972108

- AL-SayyadMJCameronJCFunctional outcome after tibial tubercle transfer for the painful patella altaClin Orthop Relat Res2002396152162

- DickschasJHarrerJReuterBSchwitullaJStreckerWTorsional osteotomies of the femurJ Orthop Res201533331832425399673

- PagenstertGWolfNBachmannMOpen lateral patellar retinacular lengthening versus open retinacular release in lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome: a prospective double-blinded comparative study on complications and outcomeArthroscopy201228678879722301361

- SingerBJSilbertBISilbertPLSingerKPThe role of botulinum toxin type a in the clinical management of refractory anterior knee painToxins2015793388340426308056

- CollinsNJBierma-ZeinstraSMCrossleyKMvan LinschotenRLVicenzinoBvan MiddelkoopMPrognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysisBr J Sports Med201347422723323242955

- LoudonJKWiesnerDGoist-FoleyHLAsjesCLoudonKLIntrarater reliability of functional performance tests for subjects with patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Athl Train200237325626112937582