Abstract

Osteitis pubis is a common cause of chronic groin pain, especially in athletes. Although a precise etiology is not defined, it seems to be related to muscular imbalance and pelvic instability. Diagnosis is based on detailed history, clinical evaluation, and imaging, which are crucial for a correct diagnosis and proper management. Many different therapeutic approaches have been proposed for osteitis pubis; conservative treatment represents the first-line approach and provides good results in most patients, especially if based on an individualized multimodal rehabilitative management. Different surgical options have been also described, but they should be reserved to recalcitrant cases. In this review, a critical analysis of the literature about athletic osteitis pubis is performed, especially focusing on its diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Introduction

Osteitis pubis is a painful chronic overuse condition affecting the pubic symphysis and surrounding soft tissues. It is characterized by pelvic pain and local tenderness over the pubic symphysis. It commonly affects athletes, especially those who participate in sports that involve kicking, turning, twisting, cutting, pivoting, sprinting, rapid acceleration and deceleration or sudden directional changes.Citation1 Osteitis pubis has been described in athletes who play sports such as soccer, rugby, ice hockey, Australian Rules football and distance running.Citation2

The diagnosis is difficult because of the anatomical complexity of the groin area, the biomechanics of the pubic symphysis region and the large number of potential sources of groin pain. Also, nomenclature is often confusing, resulting in different terms that describe similar clinical conditions.Citation3

We present a review of literature to examine the current knowledge of osteitis pubis, with particular interest in the management of athletes suffering from this condition.

Materials and methods

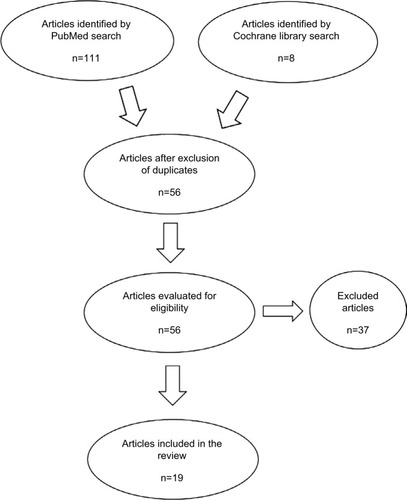

This work represents a descriptive non-systematic review on the management of osteitis pubis in athletes. A search of two databases (PubMed and Cochrane Library) was performed using the terms “osteitis pubis” or “pubalgia” in the title of articles combined with the terms “athlete,” “athletic,” “sport,” “training,” “rehabilitation” and “rehabilitative” as keywords. Search results were limited to articles written in English and published between January 1, 2012 and August 31, 2018. The decision to limit the bibliographic research to the most recent literature is due to the fact that the purpose of this article was to perform a descriptive and not a systematic review of literature. This is certainly a limitation, but it must be also considered that all recent literature is strongly influenced by the previous one. The search with the aforementioned criteria provided a total of 56 articles. As a fundamental criterion for inclusion in the review, the studies had to deal with recent concepts in the diagnosis and therapy of osteitis pubis in athletes. Articles that did not specifically concern osteitis pubis, but dealt generically with groin injuries without distinguishing osteitis pubis from the frequently associated pathologies, were excluded. Articles concerning osteitis pubis in non-athletes were also excluded. To avoid selection bias, all the authors analyzed the search results and disagreement over article inclusion was resolved by consensus. Eventually, 19 articles met the inclusion criteria and 37 articles were excluded (). Only one of the selected articles is a prospective double-blinded controlled study (level I), while most of the studies are retrospective case series, case reports or reviews of literature (). For each article, the level of evidence is defined on the basis of the classification shown in .Citation4

Table 1 Characteristics of selected studies

Table 2 Classification of levels of evidence

Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Osteitis pubis is a common source of groin pain in athletes. The incidence in athletes has been reported as 0.5%–8%, with a higher incidence in distance runners and athletes participating in kicking sports, in particular in male soccer players, who account for 10%–18% of injuries per year.Citation5,Citation6

The etiology is not completely clear and is still being debated. Muscle imbalance between the abdominal and hip adductor muscles is currently considered the most important pathogenetic factor in the development of osteitis pubis.Citation7 Abdominal muscles act synergistically with the posterior paravertebral muscles to stabilize the pelvis. They allow a single-leg stance while maintaining balance and contributing to the power and precision of the kicking leg. Stabilization during the single-leg stance also results from gluteus and adductor muscle activity. The adductors are antagonists to the abdominal muscles. Imbalances between abdominal and adductor muscle groups disrupt the equilibrium of forces around the symphysis pubis, predisposing the athlete to a subacute periostitis caused by chronic microtrauma.Citation8 Reduced internal rotation of the hip and instability of the sacroiliac joint could represent other possible predisposing factors as they lead to increased shearing stress in the pelvis.Citation9

Whatever the cause, the biomechanical overload leads to a bony stress response in the parasymphyseal bone and/or degenerative changes in the cartilage of the pubic symphysis, usually in the absence of inflammatory findings.Citation10

Diagnosis

Even though osteitis pubis is considered a self-limiting condition, players with groin pain frequently have to stop sporting activities for many months and long absence from sports is not feasible for high level athletes. For this reason, an early diagnosis and a multimodal therapeutic approach are mandatory. The diagnosis of osteitis pubis starts with recording the history and clinical evaluation. Athletes suffering from osteitis pubis typically present anterior and medial groin pain. Pain may also affect pubic symphysis, adductor musculature, lower abdominal muscles, perineal region, inguinal region or scrotum.Citation11 Pain may be unilateral or bilateral, and it is exacerbated by running, kicking, hip adduction or flexion, and eccentric loads to the rectus abdominis.Citation12

At clinical evaluation, tenderness on palpation of the symphyseal region is common. However, clinical examina tion is not standardized and includes various tests, such as lateral compression and pubic symphysis gap test with isometric adductor contraction.Citation8 Verrall et alCitation13 proposed three provocation tests (i.e., Single Adductor, Squeeze and Bilateral Adductor tests) for the assessment of chronic groin pain in athletes, with bilateral adductor test exhibiting the best metrics.Citation14 Restricted range of hip motion, positive FABER test, sacroiliac joint dysfunction and weakness of abductor or adductor muscles can be associated with clinical findings.Citation6 In addition, some authors suggest that local corticoid and/or anesthetic injections in the pubic symphysis may be helpful diagnostic tools.Citation15,Citation16

Rodriguez et alCitation8 classified athletes with osteitis pubis into four stages, based on clinical examination and diagnostic features (). However, it is not a validated classification and only empiric in nature since the authors included only a small number of patients.

Table 3 Stages of osteitis pubis

Diagnosis is challenging because of the anatomical complexity of the groin area, the biomechanics of the pubic symphysis region and the large number of potential sources of groin pain ().Citation6,Citation17 A differential diagnosis is mandatory.

Table 4 Differential diagnosis of groin pain

Imaging is not pathognomonic, but radiographs, triple-phase scintigraphy and MRI can assist physical examination and confirm diagnosis and/or exclude other pathologies and possible sources of groin pain.Citation18

Plain radiographs may demonstrate symphyseal bony sclerosis, erosions and widening or narrowing of the joint, especially in the chronic phase, while radiographic changes may be absent in the early or mild forms of the condition.Citation19

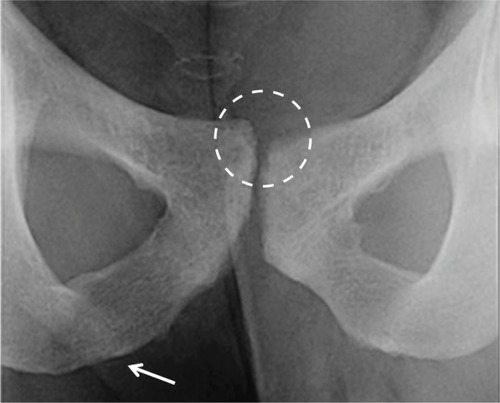

A “flamingo view” (an anterior–posterior view of the pelvis with the patient standing on one leg) can give evidence of pelvic instability (), as a vertical subluxation greater than 2 mm or a widening of the symphysis greater than 7 mm are considered pathognomonic.Citation20

Figure 2 “Flamingo view” radiograph (obtained with the patient bearing weight alternately on each leg) that shows vertical pubic subluxation greater than 2 mm and underlying degenerative changes.

Bone scintigraphy may reveal increased tracer uptake in the pubic symphysis region and parasymphyseal bone, even though the degree of uptake is poorly correlated with duration and severity of symptoms.Citation21

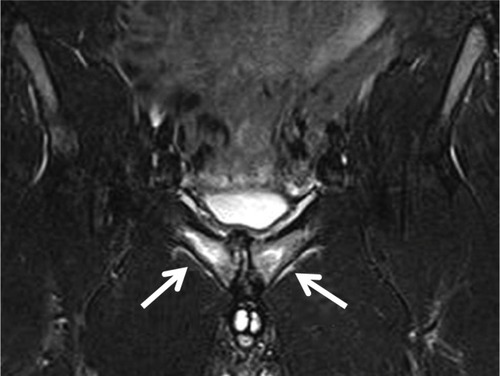

As a gold standard, MRI provides a more detailed view of the symphysis pubis and surrounding soft tissues as well as the bony pelvis and hips. The most common finding in athletic osteitis pubis of less than 6-month duration is the presence of a hyper-intense signal on T2-weighted images within the symphysis and adjacent parasymphy- seal region (); on the other hand, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral resorption with bony irregularity and osteophytosis or pubic beaking are characteristic of chronic phases.Citation7

Figure 3 Coronal T2 fat suppression MRI image showing marked bilateral diffuse symphyseal bone marrow edema and parasymphyseal edema (arrows).

Nevertheless, some studies report similar marrow edema in asymptomatic athletes also; so a correlation between MRI and clinical examination is mandatory.Citation22,Citation23

Recently, some authors proposed dynamic ultrasonography as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for evaluating osteitis pubis, but its high operator-dependency and lack of precise methodological criteria seem to determine a poor reproducibility.Citation24

Treatment and return to sport

Osteitis pubis is typically described as a self-limiting condition that improves with rest. However, management of groin pain is sometime difficult and patients can undergo extended periods of rest, which is not feasible for athletes. Different treatments have been proposed, ranging from conservative management to surgical procedures. Unfortunately, few level one studies have been published in the most recent literature and most of the scientific articles are retrospective case series or case reports, making it difficult to draw conclusions about this topic ().

Conservative treatment

Conservative management includes rest, limited activity, ice and anti-inflammatory drugs, followed by a rehabilitation program. Conservative management aims to correct muscular imbalance around the pubic symphysis, and it usually consists of a progressive exercise program, involving stretching and pelvic musculature strengthening.Citation25 Physical therapy is usually prescribed and a progressive sport-specific program is indicated before a return to sporting activities.Citation25 However, there is a lack of standard rehabilitative protocols, resulting in extremely different rehabilitative programs, with variable outcomes and time to recovery.

Recent studies underline the importance of an individualized progressive multimodal rehabilitation program.Citation26–Citation29 In this program, patients are moved through the protocol stages after they are able to perform exercises without pain and have achieved adequate levels of motion and core stability grading.Citation27,Citation29 The first stage is to focus on pain control and improve lumbo-pelvic stability. Gentle prolonged stretching, except for the adductors and ischiopubic muscles, is started. Cycling on an exercise bike is introduced as cardiovascular training. In the second stage, Swiss balls and other aids are indicated for performing resistance and strengthening exercises of the pelvis, abdominal and gluteal muscles. Abdominal core isometrics targeting the transversus abdominis, abdominal crunches, gluteal bridges with and without resistance bands, Swiss ball exercises for abdominal core, manual hip strengthening and resistance hip strengthening with band are indicated. The third and fourth stages included eccentric hip exercises, side stepping with bands, lunge and squat exercises and progressive sport-specific training. Running is gradually increased, and changes of pace and direction are introduced. To reproduce the sport requirements, athletes start training on the field, performing exercises mimicking their sport. Kicking is allowed only at the end of this stage. Eccentric abdominal wall strengthening exercises are started. Good results have been reported with this progressive rehabilitation program, despite some differences between protocols.Citation26 Most of the athletes return to pre-injury levels within 3 months (from 4 to 14 weeks). Moreover, a successful long-term follow-up was reported between 6 and 48 months for all patients.Citation30

In one of these studies, Jardì et alCitation26 described a specific conservative protocol for the treatment of six elite athletes in three different sports (two football, two basketball, two rugby players) who were diagnosed with osteitis pubis stage III and IV according to Rodriguez classification.Citation8 The average time to start squad training was 2 months, while an average of 3 months was required to return to competition. Basketball players had the shortest recovery, followed by rugby and football players. No recurrences were reported at a follow-up of at least two seasons. However, the results of this study are limited by the small cohort of included patients.

In a recent prospective double-blinded controlled level I study, Schöberl et alCitation31 analyzed amateur football players with osteitis pubis and divided them into three groups. Patients in groups 1 and 2 received an intensive 3-phase rehabilitation program. Group 1 additionally received three weekly sessions of shock wave therapy directly on the pubis, while group 2 was treated with sham shock wave therapy. The control group was treated with rest and stopping of participation in all sporting activities; they did not receive shock wave therapy. Forty-two of the 44 players of groups 1 and 2 returned to football within 4 months, but return-to-sport was significantly earlier in group 1. No recurrences were reported in both groups at 1-year follow-up. On the other hand, time to return-to-play was significantly longer (8 months) in the control group, and players frequently experienced recurrent groin pain during the first year. Physiotherapy seems to have been successful for treatment of osteitis pubis in the athletes, and local shock wave therapy significantly reduced pain, thus enabling return-to-play within 3 months of injury.Citation31 McAleer et alCitation32 described a non-operative rehabilitation program for professional and aspiring professional football players with osteitis pubis. Their rehabilitative protocol was based on a specific nine-point program that included pain control, tone reduction of over-active structures, improved range of motion at hips, pelvis and thorax, adductor strength, functional movement assessment, core stability, lumbo-pelvic control, gym-based strengthening and field-based conditioning/rehabilitation. All players returned to training, without symptoms, within 60 days and, to play, within 72 days. The authors also recommended to patients a daily prophylactic program to be followed after recovery and this may have contributed to the absence of symptom recurrence in all players at a follow-up period ranging from 16 to 33 months.

Local injections

If symptoms fail to improve with conservative measures, local injections can be used. Injections of corticosteroids in the symphyseal region and surrounding tissues have been used in various studies. However, the evidence is low. Some of these articles report resolution of pain at short-term follow-up with corticosteroids injections but a high rate of non-responders.Citation33 Moreover, despite successful return to sport participation, a large percentage of these patients continued to report pain and/or required multiple injections.Citation30 There is not enough evidence regarding the short- and long-term efficacy of corticosteroid injections.Citation33–Citation35

One study reported on prolotherapy (dextrose injections) for the treatment of recalcitrant pubalgia.Citation36 Nevertheless, the literature is very limited and the efficacy and mechanism of action of prolotherapy remain controversial.

Surgical treatment

Surgery is usually performed when conservative treatments fail. It may be indicated after at least 3 months of well-conduced rehabilitation protocol.Citation37 Surgical intervention is required for 5%–10% of patients recalcitrant to conservative approaches.Citation6

Many different open or minimally invasive surgical procedures have been proposed, including open or endoscopic curettage of the symphysis pubis, arthrodesis of the symphysis with or without bone graft and wedge resection.Citation38 All procedures can be associated with the release of the adductor tendons or with adductor enthesis repair.Citation2,Citation39–Citation41 These surgical treatments vary widely in their invasiveness, impact on pelvic biomechanics and recovery time. Even if most authors reported favorable outcomes after surgical procedures, most articles are retrospective case series, and studies are available up today.Citation6 Given the lack of adequate clinical trials, little evidence exists to support one surgical method over another, or indeed the need of surgery itself. Moreover, clinicians should evaluate cost-effectiveness and consider possible side effects of each procedure.

Gupta et alCitation42 described an endoscopic technique for pubic symphysectomy, proposing it as a safe and feasible, minimally invasive procedure for recalcitrant cases. As a complication of surgery, they reported only transient postoperative edema of the scrotum in men and of the labia in women, which resolved within 24 hours in all cases. Similar results have been reported by Matsuda et al.Citation43

Recently, some authors demonstrated the association between osteitis pubis/athletic pubalgia and femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).Citation44,Citation45 In these patients, better results have been reported after treatment of both intra and extra-articular pathologies, with a high rate of return to previous level of activity/sport.Citation46,Citation47

In a retrospective level IV study, Kajetanek et alCitation48 included 27 patients who had failed at least 3 months of appropriate conservative therapy and then underwent surgery for athletic pubalgia with injury to the abdominal wall and/or adductor attachment. Each patient received a la carte surgery, which was confined to the injured structure(s) only on the affected side (abdominal wall, adductor tendon or both), without routine contralateral procedure, with the aim of limiting morbidity and reducing recovery time. The results showed that 25 (92.6%) patients were able to return to their previous sport activity within a mean of 3–4 months and experienced no recurrence during 1-year follow-up. Time to return to play was significantly shorter in the group with abdominal wall injury only as compared to patients with adductor tendon injury only or combined injuries.

Novel approaches

Recently, other treatments have been proposed. Masala et alCitation49 in 2015 reported on pulse-dose radio frequency on 32 patients with chronic pubic pain refractory to conservative therapies. The goals of this percutaneous treatment were to denervate the genital branches of the genitor-femoral, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves and the obturator nerve. These nerves provide motor and sensory innervation of the groin region, and they can be involved in entrapment or irritation syndromes that cause pubic pain. Twenty-four patients referred a significant pain reduction at final followup (9 months) after one treatment. Six of 7 patients who were treated twice referred significant pain reduction only after the second procedure, while only one patient had no pain relief after two treatments. All patients tolerated the procedure well, with some minimal post-operative discomfort during the first few days, but without complications during the early or late period of follow-up. However, further studies are required.

Scholten et alCitation50 reported a case of distal rectus abdominis ultrasound-guided needle tenotomy and platelet-rich plasma injection, followed by a progressive rehabilitation. The patient was pain free and went back competition 8 weeks after the procedure.

Discussion

Groin pain is well-known among both athletes and physicians. Osteitis pubis is a painful degenerative condition of the pubic symphysis, surrounding soft tissues and tendons. It was first described by Beer in 1924,Citation51 and it is currently considered as one of the most debilitating pain syndromes for athletes. Although the condition is considered self-limiting, it often requires stoppage of sporting activities for several months, representing a significant problem especially for elite athletes. The etiology is still debated, but muscular imbalance and pelvic instability have been identified as the most likely pathogenetic mechanism. However, groin anatomy is complex and pain is often caused by the association of different pathologies. These may include not only intra-articular and extra-articular pathologies around the hip but also lumbar spine conditions, nerve entrapments and intra-abdominal and genitourinary pathologies. Therefore, accurate differential diagnosis is mandatory.

Many different treatment protocols and strategies have been proposed for osteitis pubis, including conservative management and rehabilitation, injections and surgery. Conservative treatment is the first-line therapeutic approach, and it includes rest, limitation of sporting activities, ice and anti-inflammatory drugs. A rehabilitative protocol aimed at correcting muscular imbalances upon pubic symphysis is also indicated.Citation52–Citation54

Despite a lack of standardized rehabilitative protocols, recent literature underlines the importance of progressive individualized rehabilitation, which usually consists of four stages. However, the lack of level 1 studies makes it difficult to compare the outcomes and a gold standard treatment is still not exploitable. Shock wave therapy can be included in the conservative treatment protocol in addition to physical exercise. Few articles are published about injection therapy, with not enough evidence regarding the efficacy of steroid injections and prolotherapy. However, promising results have been reported with the use of dextrose injections.

The relationship between athletic pubalgia and FAI is a growing topic. Although they are considered two distinct pathologies, recent studies suggest that both conditions frequently affect athletes with groin pain.Citation46 Economopoulos et alCitation55 reported that 86% of patients referring groin pain and treated for osteitis pubis and/or sports hernia had a radiographic evidence of FAI. Hammoud et alCitation56 described a consecutive series of 38 professional athletes who had been treated for symptomatic FAI. Twelve patients (32%) had undergone previous surgery for athletic pubalgia or osteitis pubis. All these patients returned to play after treatment of FAI. Furthermore, 39% of patients were diagnosed with osteitis pubis/athletic pubalgia and FAI, and they had complete resolution of pain and returned to play after surgical treatment of FAI alone. Even though the pathogenesis is not fully understood, it is possible that the restricted range of motion of the hip related to FAI may lead to compensatory stresses on the lumbar spine, pubic symphysis, sacroiliac joint and posterior acetabulum in high-performance athletes.Citation55 Excessive biomechanical stress on the groin may lead to secondary injury to the abdominal wall musculature, including the posterior inguinal wall, resulting in symptomatic osteitis pubis or groin pain disruption.Citation55

Surgery should be reserved for a limited subgroup of patients who fail conservative management, after at least 3 months of a well-conduced rehabilitative program. Many different surgical techniques have been described, but the majority of published studies exhibit a low level of evidence with no randomized controlled trials. Recent works reported better results and shorter time to return to sport, especially for patients with concurrent intra-articular pathologies such as FAI or sports hernia. Therefore, it is unclear whether the favorable outcomes are related to the treatment of concomitant pathologies or to the osteitis pubis itself.

Conclusion

Evaluation and treatment of groin pain are challenging, and a correct diagnosis is mandatory for appropriate management. Conservative treatments are indicated to stabilize the pelvis and pubic symphysis. Core stability exercises and muscle stretching and strengthening exercises of the abdominal, adductor, flexor and extensor hip muscles are effective for this purpose. Surgery is indicted for patients who do not respond to conservative management.

Despite these final considerations, it must be emphasized that this study presents some obvious limitations. First of all, the study population is limited. Second, this study is aimed at focusing only on “osteitis pubis,” which, however, is a misnomer for a variety of different pathologies which are frequently associated with osteitis pubis. Third, this review refers only to the latest literature from 2012 to 2018 and does not cover the complete literature about this topic. Therefore, given the gross heterogeneity of the studies available and the abovementioned limitations of this research, no meta-analysis could be conducted.

Nevertheless, this review could provide key directions for future investigations needed to improve our current knowledge about the management of osteitis pubis and to define the most effective therapeutic approaches.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VerrallGMHamiltonIASlavotinekJPHip joint range of motion reduction in sports-related chronic groin injury diagnosed as pubic bone stress injuryJ Sci Med Sport200581778415887904

- AngoulesAGOsteitis pubis in elite athletesWorld J Orthop20156967267926495244

- HarmonKGEvaluation of groin pain in athletesCurr Sports Med Rep20076635436118001606

- DeVriesJGBerletGCUnderstanding levels of evidence for scientific communicationFoot Ankle Spec20103420520920664009

- EkstrandJHildingJThe incidence and differential diagnosis of acute groin injuries in male soccer playersScand J Med Sci Sports1999929810310220844

- MaffulliNGiai ViaAOlivaFGroin PainVolpiPFootball Traumatology: New TrendsChamSpringer International Publishing2015303315

- OmarIMZogaACKavanaghECAthletic pubalgia and “sports hernia”: optimal MR imaging technique and findingsRadiographics20082851415143818794316

- RodriguezCMiguelALimaHHeinrichsKOsteitis Pubis Syndrome in the Professional Soccer Athlete: A Case ReportJ Athl Train200136443744012937486

- WilliamsJGLimitation of hip joint movement as a factor in traumatic osteitis pubisBr J Sports Med1978123129133719321

- VerrallGMHenryLFazzalariNLSlavotinekJPOakeshottRDBone biopsy of the parasymphyseal pubic bone region in athletes with chronic groin injury demonstrates new woven bone formation consistent with a diagnosis of pubic bone stress injuryAm J Sports Med200836122425243118927251

- FrickerPATauntonJEAmmannWOsteitis pubis in athletes: infectioninflammation or injury? Sports Med19911242662791784877

- BraunPJensenSHip pain – a focus on the sporting populationAust Fam Physician2007366410413

- VerrallGMSlavotinekJPBarnesPGFonGTDescription of pain provocation tests used for the diagnosis of sports-related chronic groin pain: relationship of tests to defined clinical (pain and tenderness) and MRI (pubic bone marrow oedema) criteriaScand J Med Sci Sports2005151364215679570

- HegedusEJSternBReimanMPTararaDWrightAAA suggested model for physical examination and conservative treatment of athletic pubalgiaPhys Ther Sport201314131623312727

- MurarJBirminghamPOsteitis Pubis Hip Arthroscopy and Hip Joint Preservation SurgeryNew YorkSpringer2014737749

- HoppSOjoduIJainAFritzTPohlemannTKelmJNovel patho-morphologic classification of capsulo-articular lesions of the pubic symphysis in athletes to predict treatment and outcomeArch Orthop Trauma Surg2018138568769729417208

- BisciottiGNAuciADi MarzoFGroin pain syndrome: an association of different pathologies and a case presentationMuscles Ligaments Tendons J20155321422226605198

- ZogaACKavanaghECOmarIMAthletic pubalgia and the “sports hernia”: MR imaging findingsRadiology2008247379780718487535

- HarrisNHMurrayROLesions of the symphysis in athletesBr Med J1974459382112144422968

- WilliamsPRThomasDPDownesEMOsteitis pubis and instability of the pubic symphysis. When nonoperative measures failAm J Sports Med200028335035510843126

- VerrallGMSlavotinekJPFonGTIncidence of pubic bone marrow oedema in Australian rules football players: relation to groin painBr J Sports Med2001351283311157458

- BeattyTOsteitis pubis in athletesCurr Sports Med Rep2012112969822410702

- LovellGGallowayHHopkinsWHarveyAOsteitis pubis and assessment of bone marrow edema at the pubic symphysis with MRI in an elite junior male soccer squadClin J Sport Med200616211712216603880

- OrchardJWReadJWNeophytonJGarlickDGroin pain associated with ultrasound finding of inguinal canal posterior wall deficiency in Australian Rules footballersBr J Sports Med19983221341399631220

- FrizzieroAVittadiniFPignataroAConservative management of tendinopathies around hipMuscles Ligaments Tendons J20166328129228066732

- JardíJRodasGPedretCOsteitis pubis: can early return to elite competition be contemplated?Transl Med UniSa201410525825147768

- JaroszBSIndividualized multi-modal management of osteitis pubis in an Australian Rules footballerJ Chiropr Med201110210511022014865

- SudarshanAPhysical therapy management of osteitis pubis in a 10-year-old cricket fast bowlerPhysiother Theory Pract201329647648623270404

- VijayakumarPNagarajanMRamliAMultimodal physiotherapeutic management for stage-IV osteitis pubis in a 15-year old soccer athlete: a case reportJ Back Musculoskelet Rehabil201225422523023220803

- CheathamSKolberMJShimamuraKKThe effectiveness of nonoperative rehabilitation programs for athletes diagnosed with osteitis pubisJ Sport Rehabil2015254399403

- SchöberlMPrantlLLooseONon-surgical treatment of pubic overload and groin pain in amateur football players: a prospective double-blinded randomised controlled studyKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc20172561958196628093636

- McAleerSLippieENormanDRiepenhofHManagement of osteitis pubis/pubic bone stress in professional soccer players using a nonoperative rehabilitation protocol with clinical and functional progression criteriaJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201747968369028774219

- ChoiHMcCartneyMBestTMTreatment of osteitis pubis and osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis in athletes: a systematic reviewBr J Sports Med2011451576418812419

- ElattarOChoiHDillsVDBusconiBGroin Injuries (Athletic Pubalgia) and Return to PlaySports Health20168431332327302153

- KelmJLudwigOAndréJMaasSHoppSWhat do we know about osteitis pubis in athletes?Sportverletz Sportschaden Epub201828

- TopolGAReevesKDRegenerative injection of elite athletes with career-altering chronic groin pain who fail conservative treatment: a consecutive case seriesAm J Phys Med Rehabil2008871189090218688199

- ValentAFrizzieroABressanSZanellaEGiannottiEMasieroSInsertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis in athletes: a reviewMuscles Ligaments Tendons J20122214214823738289

- WilliamsPRThomasDPDownesEMOsteitis pubis and instability of the pubic symphysis. When nonoperative measures failAm J Sports Med200028335035510843126

- MaffulliNLoppiniMLongoUGDenaroVBilateral mini-invasive adductor tenotomy for the management of chronic unilateral adductor longus tendinopathy in athletesAm J Sports Med20124081880188622707750

- HoppSJCulemannUKelmJPohlemannTPizanisAOsteitis pubis and adductor tendinopathy in athletes: a novel arthroscopic pubic symphysis curettage and adductor reattachmentArch Orthop Trauma Surg201313371003100923689650

- HoppSTuminMWilhelmPPohlemannTKelmJArthroscopic pubic symphysis debridement and adductor enthesis repair in athletes with athletic pubalgia: technical note and video illustrationArch Orthop Trauma Surg2014134111595159925055756

- GuptaARedmondJMHammarstedtJEEndoscopic Pubic Symphysectomy for Recalcitrant Osteitis PubisArthrosc Tech201542e115e11726052486

- MatsudaDKSehgalBMatsudaNAEndoscopic Pubic Symphysectomy for Athletic Osteitis PubisArthrosc Tech201543e251e25426258039

- StrosbergDSEllisTJRentonDBThe role of femoroacetabular impingement in core muscle injury/athletic pubalgia: diagnosis and managementFront Surg20163626904546

- RambaniRHackneyRLoss of range of motion of the hip joint: a hypothesis for etiology of sports herniaMuscles Ligaments Tendons J201551293225878984

- LarsonCMSports hernia/athletic pubalgia: evaluation and managementSports Health20146213914424587864

- RossJRStoneRMLarsonCMCore muscle injury/sports hernia/athletic pubalgia, and femoroacetabular impingementSports Med Arthrosc Rev201523421322026524557

- KajetanekCBenoîtOGrangerBAthletic pubalgia: Return to play after targeted surgeryOrthop Traumatol Surg Res2018104446947229549038

- MasalaSFioriRRagusoMPulse-dose radiofrequency in athletic pubalgia: preliminary resultsJ Sport Rehabil201726322723327632851

- ScholtenPMMassimiSDahmenNDiamondJWyssJSuccessful treatment of athletic pubalgia in a lacrosse player with ultrasound-guided needle tenotomy and platelet-rich plasma injection: a case reportPM R201571798325134854

- SchnuteWJOsteitis pubisClin Orthop19612018719213748321

- FrizzieroATrainitoSOlivaFNicoli AldiniNMasieroSMaffulliNThe role of eccentric exercise in sport injuries rehabilitationBr Med Bull20141101477524736013

- Dello IaconoAMaffulliNLaverLPaduloJSuccessful treatment of groin pain syndrome in a pole-vault athlete with core stability exerciseJ Sports Med Phys Fitness201757121650165927792221

- HölmichPUhrskouPUlnitsLEffectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trialLancet199935391514394439989713

- EconomopoulosKJMilewskiMDHanksJBHartJMDiduchDRRadiographic evidence of femoroacetabular impingement in athletes with athletic pubalgiaSports Health20146217117724587869

- HammoudSBediAMagennisEMeyersWCKellyBTHigh incidence of athletic pubalgia symptoms in professional athletes with symptomatic femoroacetabular impingementArthroscopy201228101388139522608890

- HenningPTThe running athlete: stress fractures, osteitis pubis, and snapping hipsSports Health20146212212724587861

- McAleerSSGilleJBarkSRiepenhofHManagement of chronic recurrent osteitis pubis/pubic bone stress in a Premier League footballer: Evaluating the evidence base and application of a nine-point management strategyPhys Ther Sport201516328529926150099

- RossidisGPerryAAbbasHLaparoscopic hernia repair with adductor tenotomy for athletic pubalgia: an established procedure for an obscure entitySurg Endosc201529238138624986020

- EllsworthAAZolandMPTylerTFAthletic pubalgia and associated rehabilitationInt J Sports Phys Ther20149677478425383246