Abstract

Although treat-to-target goals for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been well-established through several guidelines in recent years, concerns regarding treat-to-prevent goals for RA remain unclear. RA patients are typically subjected to over- or under-treatment because it is difficult for clinicians to determine the prognosis of RA patients. This typically results in failure to select and identify patient subsets that should receive monotherapy or combination therapy to treat early RA. Understanding treat-to-prevent goals, as well as unfavorable prognoses, risk factors, and prediction methods for RA, is therefore critical for making treatment decisions. Rapid radiographic progression plays a central role in contributing to other composite RA indices, so this may be the best method for defining treat-to-prevent goals for RA. Accordingly, risk factors of rapid radiographic progression have been defined and two prediction models were retrospectively derived based on clinical trial data. Additional studies are required to develop risk models that can be used for accurate predictions.

Introduction

Doctors experience significant difficulty in choosing between monotherapy and combination therapy for treating early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. Several studies have suggested that combination therapy with conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and novel biologic agents may be effective during early stages of the disease and may influence the long-term prognosis; however, some early RA patients may achieve clinical remission through the use of a single DMARD.Citation1,Citation2 Accordingly, this subset of RA patients may be over-treated with the use of combination DMARDs, while other patients may achieve poor treatment response with a single drug. Therefore, selecting and identifying patient subsets to receive monotherapy or combination therapy is critical for properly treating early RA. During the 75th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), several concerns regarding the 2012 ACR recommendations for treating RA were discussed. Similar to the 2008 ACR recommendations,Citation3 prognostic assessment of RA was emphasized as a necessary precondition for treatment decisions. The use of monotherapy or combination therapy should be recommended depending upon predictions to determine whether RA patients have a favorable or unfavorable prognosis.

Thus, guidelines should be set that can be used to determine whether the prognosis is favorable or unfavorable. Currently, no guidelines exist to differentiate between poor outcomes and good outcomes for RA treatment.Citation4 Although various clinical composite indices such as the disease activity score, disease activity score in 28 joints, simplified disease activity index (SDAI), clinical disease activity index, health assessment questionnaire, modified health assessment questionnaire, multidimensional health assessment questionnaire, and routine assessment of patient index data, are widely used in clinical practice, these indices are often only useful for evaluating disease activity but not for describing treatment outcomes.Citation5

Additionally, risk factors for poor treatment outcomes are not well-defined. Various environment, patient, and disease-associated predictive factors have been proposed for both early and late RA, but their usefulness in guiding treatment choices at the individual level remains unclear. It remains difficult for rheumatology doctors to translate predictions into treatment choices for individual patients recently diagnosed with RA. Additional concerns include effective prediction of treatment outcomes, the usefulness of risk factors, and making treatment decisions based on currently existing evidence. The answers to these questions remain unclear.

Treat-to-target goals versus treat-to-prevent goals

Generally, a good outcome for a disease is considered total recovery or clinical remission. Since total recovery from RA is not possible, clinical remission is considered a good outcome or a treat-to-target goal.Citation6 Threshold score for clinical remission were clearly defined in the disease activity score (<1.6), disease activity score in 28 joints (<2.6), SDAI (<3.3), clinical disease activity index (<2.8), health assessment questionnaire (≤0.5), modified health assessment questionnaire (≤3.0), multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (≤3.0), and routine assessment of patient index data (≤3.0).Citation5,Citation7 Furthermore, recently published recommendations established by the ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism define clinical remission of RA as tender joint count, swollen joint count (SJC), C-reactive protein (CRP, mg/dL), and patient global assessment (on a 0–10 scale) all of ≤1 or and SDAI of ≤3.3.Citation8 These definitions are clinically practicable and widely accepted as treat-to-target goals for RA; however, definitions of poor treatment outcomes or treat-to-prevent goals are vague. Though low, moderate, and high disease activity have been described in some of these composite indices, these activities may not be appropriate for use as prevention goals. Treatment of RA guided by these composite indices is not sufficient for achieving clinical and radiological remission.Citation9 Furthermore, varying levels of disease activity may not necessarily be a poor treatment outcome for RA. For example, moderate RA activity may be considered a treatment failure if baseline disease activity was low, while treatment may be defined as successful if baseline RA activity was high. Contradictions arise for these multichotomous dependent variables because disease states are described at single time points while disease changes are not described. Thus, treatment outcome should be defined in reference to the level of improvement or deterioration. ACR response criteria (ACR 20, ACR 50, and ACR 70), another composite index, describe the percentage of disease improvement and compare disease activity at two discrete time points; however, these criteria are used to discriminate effective treatment from placebo treatment based on clinical trial data and are not directly applicable to clinical practice.Citation10

Thus, treat-to-prevent goal of early RA must be defined. Additionally, disease conditions that should actively be prevented may include death, systemic features, pains, red swelling, joint deformation, and limb disability. Because RA itself is not a fatal disease, it is not reasonable to define treat-to-prevent goals of early RA as death. In clinical practice, prevention of death is not considered a primary goal when treating RA. Moreover, reduction of pain, red swelling, or systemic features does not necessarily indicate the disease has been effectively controlled.

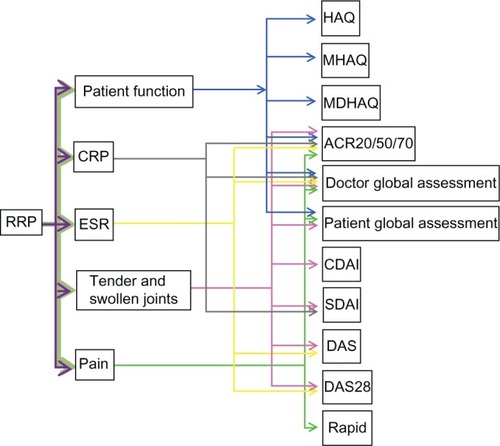

From a clinical perspective, joint deformation, ankylosis, and limb disability are unfavorable outcomes for most early RA patients not receiving drugs or in those receiving DMARD monotherapy. The pathological nature of lesions involving bone and cartilage erosion and destruction eventually results in joint narrowing and fusion.Citation4 Iconography is a descriptive method used to record these pathological changes.Citation11 The Sharp/van der Heijde score (SHS), an iconography rating system, was shown to be closely associated with joint deformation and limb disability; and over a period of time (typically 1 year), a rapid increase in the SHS predicts a high probability of disability.Citation12 Accordingly, a novel index, rapid radiographic progression (RRP), was defined as SHS ≥ 5 U/1 year.Citation13 RRP is typically accompanied by severe pain, joint swelling and tenderness, high titer CRP and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), which contribute significantly to RA composite indices (). Therefore, RRP plays a central role in contributing to other composite RA indices.

Figure 1 RRP plays a centre role in contributing to other composite RA indices. Because of bone and cartilage erosion and destruction, RRP usually causes severe pains, joint tenderness, swelling, elevated CRP titer and ESR, which weigh heavily in determining several indices of RA, like ACR response criteria, DAS and DAS28, CDAI, SDAI, HAQ and MHAQ, RAPID and MDHAQ.

In clinical practice, RRP typically occurs in a minority of treated patients; effective therapy in these patients can reduce the odds of progression by up to 78%. Furthermore, early and intensive treatment can slow the rate of radiographic progression.Citation14 Identifying individual RA patients at high risk for RRP is therefore critical to making appropriate treatment choices.Citation13 RRP directly indicates a poor outcome for RA patients; thus, it may be the most appropriate marker for defining treat-to-prevent goals for RA.

Risk factors for RRP

Previous studies have indicated that several conditions are associated with unfavorable prognosis of RA (). Human leukocyte antigen-DRB1Citation15–Citation17 and protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor 22 genes,Citation18–Citation20 anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA),Citation21–Citation27 ESR,Citation28,Citation29 CRP,Citation30,Citation31 rheumatoid factor (RF),Citation32 and erosion scoreCitation33 are well-established risk factors associated with an unfavorable prognosis of RA, while other conditions, such as smoking,Citation34–Citation36 female sex,Citation37–Citation39 old age,Citation40,Citation41 psychological factors,Citation42 and low level of formal educationCitation43 show inconsistent associations with RA prognosis. Clearly, the definition of an unfavorable prognosis is vague and therefore cannot be interpreted as RRP. Thus, whether these conditions are associated with RRP is unknown.

Table 1 Risk factors for unfavorable prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis

With the data from an active-controlled study known as Patients Receiving Infliximab (IFX) for the Treatment of RA of Early Onset performed by St Clair et al,Citation13 this question was partially answered. This double-blind study involved 1049 early RA patients randomly assigned to receive methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy or MTX in combination with IFX over 46 weeks to establish a correlation between RRP and baseline risk factors, including CRP, ESR, SJC, and RF. In these 1049 patients, high titer CRP, RF, and high ESR and SJC are typically suggestive of a high percentage of RRP. Another study reported a similar correlation between CRP, RF, ACPA, erosion score, and RRP.Citation48 In these two studies CRP, ESR, RF, SJC, ACPA, erosion score, and treatment methods were considered baseline risk factors for predicting the potential for RRP. Additionally, different treatment (monotherapy of MTX and combination therapy of MTX plus IFX) significantly influenced RRP rate. Conservative treatment (monotherapy) typically resulted in a higher RRP rate, while aggressive treatment (combination therapy) remarkably decreased RRP rate. A close correlation between clearly defined risk factors and clearly defined poor outcomes for RA was established. Developing a method for prognostic prediction of RA is now possible.

Risk models

One risk model was derived based on trichotomous variables, including CRP (<0.6, 0.6–3 or >3 mg/dL), ESR (<21, 21–50 or >50 mm/h), RF (<80, 80–200 or >200 U/mL), SJC (<10, 10–17 or >17), and treatment method.Citation13 These variables of different levels define a series of subgroups in the 1049 early RA patients. RRP rate in each subgroup reveals the likelihood of RRP in an RA in this subgroup. A similar model derived by Visser et al was based on CRP, RF, ACPA, and erosion score.Citation48 This risk model was established based on data from a smaller population of 465 RA patients. Clearly in both risk models, the number of subjects in each subgroup is not sufficient to achieve a representative RRP rate. Additionally, CRP level in both models is significantly different, suggesting a large difference between these two early RA populations. Therefore, larger studies need to be conducted to obtain epidemiological data from early RA patients under monotherapy or combination therapy; this will help to establish a more powerful risk model for predicting RA outcomes.

Conclusion

The cause of RA is unknown and the prognosis is not easy to predict. Although several composite indices have been well-defined for predicting a good prognosis, treat-to-target goals for RA, the definition, and risk factors for poor prognosis are unclear. RRP plays a central role in contributing to most composite RA indices and directly reflects poor outcomes of RA; Thus, RRP may be the most suitable marker for defining the treat-to-prevent goals. Identifying individual RA patients at a high risk of RRP is therefore critical to making appropriate treatment decisions. Several risk factors have been described to be closely associated with RRP. Some risk models use these risk factors to predict the probability of RRP; however, these risk models were developed retrospectively. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to develop more powerful risk models.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KuriyaBArkemaEVBykerkVPKeystoneECEfficacy of initial methotrexate monotherapy versus combination therapy with a biological agent in early rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of clinical and radiographic remissionAnn Rheum Dis20106971298130420421343

- AllaartCFHuizingaTWTreatment strategies in recent onset rheumatoid arthritisCurr Opin Rheumatol201123324124421346574

- SaagKGTengGGPatkarNMAmerican College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritisArthritis Rheum200859676278418512708

- McInnesIBSchettGThe pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritisN Engl J Med2011365232205221922150039

- SokkaTHow should rheumatoid arthritis disease activity be measured today and in the future in clinical care?Rheum Dis Clin North Am201036224325720510232

- JayakumarKNortonSDixeyJSustained clinical remission in rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence and prognostic factors in an inception cohort of patients treated with conventional DMARDSRheumatology (Oxford)201251116917522096011

- van TuylLHFelsonDTWellsGSmolenJZhangBBoersMEvidence for predictive validity of remission on long-term outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic reviewArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062110811720191498

- Iking-KonertCAringerMWollenhauptJPerformance of the new 2011 ACR/EULAR remission criteria with tocilizumab using the phase IIIb study TAMARA as an example and their comparison with traditional remission criteriaAnn Rheum Dis201170111986199021875873

- RezaeiHSaevarsdottirSForslindKIn early rheumatoid arthritis, patients with a good initial response to methotrexate have excellent 2-year clinical outcomes, but radiological progression is not fully prevented: data from the methotrexate responders population in the SWEFOT trialAnn Rheum Dis201271218619121930734

- RanganathVKKhannaDPaulusHEACR remission criteria and response criteriaClin Exp Rheumatol2006246 Suppl 43S-142116466620

- YangMXiaoCWuQAnti-inflammatory effect of Sanshuibaihu decoction may be associated with nuclear factor-kappa B and p38 MAPK alpha in collagen-induced arthritis in ratJ Ethnopharmacol2010127226427319914365

- van den BroekMDLDRapid radiological progression in the first year of rheumatoid arthritis predicts both disability and radiological joint damage progression over 8 years of targeted treatmentArthritis Rheum201163Suppl 10418

- VastesaegerNXuSAletahaDSt ClairEWSmolenJSA pilot risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritisRheumatology (Oxford)20094891114112119589891

- KyburzDGabayCMichelBAFinckhAThe long-term impact of early treatment of rheumatoid arthritis on radiographic progression: a population-based cohort studyRheumatology (Oxford)20115061106111021258051

- GormanJDLumRFChenJJSuarez-AlmazorMEThomsonGCriswellLAImpact of shared epitope genotype and ethnicity on erosive disease: a meta-analysis of 3,240 rheumatoid arthritis patientsArthritis Rheum200450240041214872482

- Delgado-VegaAMAnayaJMMeta-analysis of HLA-DRB1 polymorphism in Latin American patients with rheumatoid arthritisAutoimmun Rev20076640240817537386

- VosKVisserHSchreuderGMTHuman leukocyte antigen-DQ and DR polymorphisms predict rheumatoid arthritis outcome better than DR aloneHum Immunol200162111217122511704283

- HinksABartonAJohnSAssociation between the PTPN22 gene and rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a UK population: further support that PTPN22 is an autoimmunity geneArthritis Rheum20055261694169915934099

- BegovichABCarltonVEHHonigbergLAA missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritisAm J Hum Genet200475233033715208781

- GregersenPKPathways to gene identification in rheumatoid arthritis: PTPN22 and beyondImmunol Rev20052041748615790351

- NishimuraKSugiyamaDKogataYMeta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody and rheumatoid factor for rheumatoid arthritisAnn Intern Med20071461179780817548411

- EmadYShehataMRagabYSaadAHamzaHAbou-ZeidAPrevalence and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies for future development of rheumatoid arthritis in early undifferentiated arthritisMod Rheumatol201020435836520364358

- AvouacJGossecLDougadosMDiagnostic and predictive value of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature reviewAnn Rheum Dis200665784585116606649

- van VenrooijWJZendmanAJPruijnGJAutoantibodies to citrullinated antigens in (early) rheumatoid arthritisAutoimmun Rev200661374117110315

- ZendmanAJVossenaarERvan VenrooijWJAutoantibodies to citrullinated (poly)peptides: a key diagnostic and prognostic marker for rheumatoid arthritisAutoimmunity200437429529915518045

- BukhariMThomsonWNaseemHBunnDThe performance of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in predicting the severity of radiologic damage in inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis RegisterArthritis Rheum20075692929293517763407

- MeyerOLabarreCDougadosMAnticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody assays in early rheumatoid arthritis for predicting five year radiographic damageAnn Rheum Dis200362212012612525380

- CourvoisierNDougadosMCantagrelAPrognostic factors of 10-year radiographic outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective studyArthritis Res Ther2008105R10618771585

- SilvaIMateusMBrancoJCAssessment of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) on rheumatoid arthritis activity predictionActa Reumatol Port201035545646221245814

- SalaffiFCarottiMCiapettiAGaspariniSFilippucciEGrassiWRelationship between time-integrated disease activity estimated by DAS28-CRP and radiographic progression of anatomical damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritisBMC Musculoskelet Disord20111212021624120

- PopeJEThorneCHaraouiBPTruongDPsaradellisESampalisJSDoes C-reactive protein add value in active rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Optimization of Humira TrialScand J Rheumatol201140323223321108544

- Ibn YacoubYAmineBLaatirisAHajjaj-HassouniNRheumatoid factor and antibodies against citrullinated peptides in Moroccan patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with disease parameters and quality of lifeClin Rheumatol201231232933421814754

- DixeyJSolymossyCYoungAIs it possible to predict radiological damage in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA)? A report on the occurrence, progression, and prognostic factors of radiological erosions over the first 3 years in 866 patients from the Early RA Study (ERAS)J Rheumatol Suppl200469485415053454

- PapadopoulosNGAlamanosYVoulgariPVEpagelisEKTsifetakiNDrososAADoes cigarette smoking influence disease expression, activity and severity in early rheumatoid arthritis patients?Clin Exp Rheumatol200523686186616396705

- MikulsTRHughesLBWestfallAOCigarette smoking, disease severity and autoantibody expression in African Americans with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis200867111529153418198196

- FinckhADehlerSCostenbaderKHGabayCCigarette smoking and radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis20076681066107117237117

- IikuniNSatoEHoshiMThe influence of sex on patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large observational cohortJ Rheumatol200936350851119208610

- SokkaTTolozaSCutoloMWomen, men, and rheumatoid arthritis: analyses of disease activity, disease characteristics, and treatments in the QUEST-RA studyArthritis Res Ther2009111R719144159

- MerlinoLACerhanJRCriswellLAMikulsTRSaagKGEstrogen and other female reproductive risk factors are not strongly associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis in elderly womenSemin Arthritis Rheum2003332728214625816

- CamachoEMVerstappenSMLuntMBunnDKSymmonsDPInfluence of age and sex on functional outcome over time in a cohort of patients with recent-onset inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis RegisterArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163121745175222127966

- Amador-PatarroyoMJRodriguez-RodriguezAMontoya-OrtizGHow does age at onset influence the outcome of autoimmune diseases?Autoimmune Dis2012201225173022195277

- LorishCDAbrahamNAustinJBradleyLAAlarconGSDisease and psychosocial factors related to physical functioning in rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol1991188115011571834844

- PincusTCallahanLFFormal education as a marker for increased mortality and morbidity in rheumatoid arthritisJ Chronic Dis198538129739844066893

- HayemGChazerainPCombeBAnti-Sa antibody is an accurate diagnostic and prognostic marker in adult rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol19992617139918234

- Nyhall-WahlinBMPeterssonIFNilssonJAJacobssonLTTuressonCHigh disease activity disability burden and smoking predict severe extra-articular manifestations in early rheumatoid arthritisRheumatology (Oxford)200948441642019213849

- van LeeuwenMAvan der HeijdeDMvan RijswijkMHInterrelationship of outcome measures and process variables in early rheumatoid arthritis. A comparison of radiologic damage, physical disability, joint counts, and acute phase reactantsJ Rheumatol19942134254297516430

- KayeBRKayeRLBobroveARheumatoid nodules. Review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative casesAm J Med19847622792926364806

- VisserKGoekoop-RuitermanYPde Vries-BouwstraJKA matrix risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving different dynamic treatment strategies: post hoc analyses from the BeSt studyAnn Rheum Dis20106971333133720498212