Abstract

Appendicitis is a common abdominal surgical emergency. However, treatment becomes more complex when the patient is pregnant. It is important to consider the diagnostic differences in pregnant and non-pregnant patients, as well as the changes to surgical and non-surgical management. Commonly, appendicitis in pregnancy is diagnosed with radiographic imaging, preferably ultrasound or MRI. Due to increased risk with delay to surgery, surgical management is recommended, as opposed to non-operative management, and ultimately a laparoscopic appendectomy is the surgery of choice. We aim to provide a comprehensive review of the best practices and clinical management of appendicitis in pregnancy.

Introduction

Appendicitis is defined as “an inflammation of the appendix that may lead to an abscess, ileus, peritonitis, or death if untreated”. It is one of the most common abdominal surgical emergencies and is currently treated with surgery if deemed uncomplicated.Citation1 However, pregnancy increases the complexity of diagnosis and treatment of appendicitis. We seek to discuss the diagnosis of appendicitis in pregnancy, as well as the operative and non-operative differences between management in pregnant patients vs non-pregnant patients. It is critical to consider these differences to allow for safe treatment of both mother and fetus.

Causes

Appendicitis was historically thought to be associated with obstruction of the appendiceal lumen – often by appendicolith (stone of the appendix) or other mechanical etiology. Other causes of obstruction also include appendiceal tumors such as adenocarcinoma, hypertrophied lymphatic tissue and carcinoid tumors.Citation2 However, studies measuring the pressure in the appendix pre-operatively have shown that only one-third of cases are caused by obstruction.Citation3 Ultimately, appendicitis is an inflammation of the organ wall, and inflammation is followed by localized ischemia, perforation, and further infectious development. Bacteria build up in the appendix, leading to inflammation and possible perforation and abscess formation.Citation4 Men and women are both affected by appendicitis with lifetime incidence slightly higher in men – 8.6% vs 6.7%.Citation4,Citation5 Most often, appendicitis occurs between the ages of 5 and 45, with a mean age at presentation of 28.Citation4

Appendicitis is typically a clinical diagnosis based on history and physical examination, laboratory results, and imaging.Citation1,Citation6 History and physical examination may reveal initial vague periumbilical pain with migration to the right lower quadrant, nausea, vomiting, fever, rebound tenderness over McBurney’s point (1.5 to 2 inches from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) on a straight line from the ASIS to the umbilicus), and indirect tenderness (right lower quadrant pain elicited by palpation of the left lower quadrant).Citation1,Citation2 Other physical exam signs such as psoas sign (pain on external rotation or passive extension of right hip) or obturator sign (pain on internal rotation of the right hip) are rarer, and in reality not used.Citation4

Changes with Pregnancy

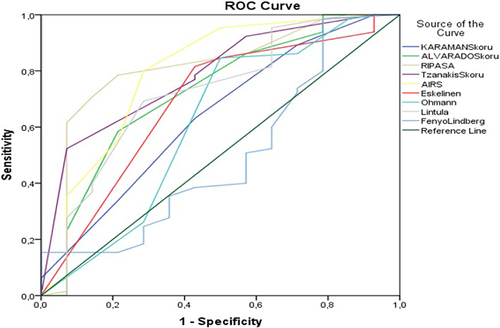

The diagnosis rate of acute appendicitis in pregnancy has been reported to be around 7 per 10,000 person-years during the first two trimesters, and 4.6 per 10,000 person years, compared to the incidence of acute appendicitis in the general population – approximately 2.45 per 10,000 person-years.Citation2,Citation4,Citation7–9 As previously mentioned, appendicitis often affects patients age 5 through 45 (with an average age of 28) which also includes a woman’s childbearing years, as well as average year for first childbirth of approximately 26.Citation4,Citation10 Diagnosis becomes difficult in pregnancy due to the presence of a gravid uterus and potential displacement of appendix from its normal anatomic position. Many appendicitis clinical scoring methods exist – including Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohmann, AIR, RIPASA, Tzanakis, Lintula, Fenyo-Lindberg, and Karaman systems.Citation11 According to a single-center retrospective study, the Tzanakis system was the most effective scoring system in non-pregnant women, while the RIPASA was the best scoring system for pregnant patients with the PPV (positive predictive value) at 94.40%, NPV (negative predictive value) at 44%, and sensitivity and specificity were 78.46% and 78.57%, respectively ().Citation11 The RIPASA score includes parameters such as: sex, age, migration of pain, anorexia, fever, Rovsing’s sign, etc.Citation12 ().

Figure 1 ROC curves for diagnostic performance of appendicitis scoring systems in pregnant women.

Table 1 RIPASA Score for Acute Appendicitis

Many symptoms of acute appendicitis may be confused with clinical manifestations of pregnancy. As mentioned, physical exam findings may not follow standard patterns as the gravid uterus may displace the appendix. Previous studies have reported the appendiceal displacement into the right upper quadrant, as high as the right hypochondrium. Alternatively, there are reports of the appendix not changing location in the abdomen from the right lower quadrant.Citation13 This inconsistency in the location of the appendix in the pregnant patient decreases the reliability of history and physical exam in diagnosing acute appendicitis in this patient population. In addition, the white blood count is typically mildly elevated in pregnancy. The World Society of Emergency Surgery recommends not diagnosing acute appendicitis in pregnant patients on symptoms and signs alone, and emphasizes the importance to requesting laboratory testing and inflammatory markers (eg, CRP).Citation14

Imaging with Pregnancy

Suspected appendicitis in pregnant patients can be investigated with several imaging modalities. Ultrasound can be utilized with the same diagnostic criteria used for non-pregnant patients – which includes visualization of a blind-ending, dilated (>6–7 mm in diameter) aperistaltic and noncompressible tubular structure arising from the cecum.Citation15–17 Although ultrasound is the initial imaging modality used at many institutions for pregnant patients with suspected appendicitis, ultrasound has several limitations. Particularly, a large body habitus increases difficulty in obtaining a clear view of the appendix. Overlying bowel, gas, and the gravid uterus increases that difficulty further.Citation18 Due to these barriers, the appendix can only be visualized in pregnant patients approximately 60% of the time.Citation19

Other imaging modalities can be used when ultrasound is inconclusive, or if additional resources are available.

While MR imaging can be used to visualize the appendix, intravenous gadolinium cannot be used in pregnant patients.Citation15 A normal appendix on MR imaging has the following appearance: <6 mm diameter, appendiceal wall thickness <2 mm, low luminal signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images, and no peri-appendiceal fat stranding or fluid.Citation15,Citation20 Alternatively, MR imaging features of appendicitis include diameter >7 mm, appendiceal wall thickness >2 mm, appendicoliths and surrounding hyperechoic inflamed fat or hypoechoic fluid on T2-weighted images.Citation15,Citation16 MRI is reported as the safest imaging modality in pregnancy, with a lack of consensus regarding the risk to the fetus. However, some studies have reported potential teratogenic effects and acoustic damages.Citation21,Citation22 The heating effort of MR gradient changes and direct non-thermal interaction of electromagnetic field have been raised as concerning when MRI is performed early in pregnancy.Citation21,Citation23

CT is also an option for imaging in diagnosing appendicitis in pregnancy. However, the risk of exposing the fetus to ionizing radiation that must be considered. Ionizing radiation exposure to a fetus can increase risks of congenital malformations, mental retardation, microcephaly, and embryonic and fetal death.Citation24 It has been previously reported that fetal mortality is greatest when radiation exposure occurs within the first week of conception. Within the first trimester, the embryo is very vulnerable to growth retarding, teratogenic, and lethal effects in weeks 3–6 post conception.Citation24 The vulnerability to multiple organ teratogenesis decreases in weeks 8–15, but the CNS and growth potential is still at risk to be significantly affected.Citation24 The fetus is more likely to be resistant to potential harm during second and third trimesters, although a slight risk of adverse effects remains.Citation25 CT scans are routinely clinically done to evaluate for and diagnose appendicitis in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Radiation dosage is important to consider in pregnant patients. 50–100 mGy has been recommended as the cumulative radiation dose to the fetus during pregnancy.Citation19 CT of the pelvis is less than 30 mGy, while a plain abdominal radiograph is approximately 1–3 mGy, so these modalities, while associated with risk, are not absolutely contraindicated.Citation19 Ultimately, due to ultrasound’s limitations, including low accuracy and false-negatives, MRI is the preferred first-line imaging study.Citation14,Citation26,Citation27

Management

Laparoscopic (as opposed to open) appendectomy has become the gold standard for surgical management of appendicitis due to shorter lengths of stays, decreased need for analgesia, earlier food tolerance, earlier return to work, and lower infection rates.Citation28,Citation29 Comparative outcomes of laparoscopic and open appendectomy show similar trends in pregnancy – laparoscopic approach results in shorter operative time, length of stay, and complication rate.Citation30 According to the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES), a laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed safely in any trimester of pregnancy and is the standard of care.Citation19,Citation31,Citation32 The World Society of Emergency Surgery also suggests that laparoscopic appendectomy is preferred to open appendectomy when surgery is indicated.Citation14 This mirrors trends seen with laparoscopic surgery as a whole and is not just applicable to appendicitis and/or pregnant patients.Citation33,Citation34 Historic studies suggested that the safest trimester to operate laparoscopically was the second trimester; however, newer studies have demonstrated that there is minimal difference in safety regardless of trimester during which the operation takes place.Citation19,Citation35 These previous studies cited concerns with spontaneous abortions in the first trimester and pre-term labor in the third trimester.Citation35,Citation36 More recent literature shows there is risk associated with waiting until the second trimester or until after delivery, including infection or perforation. These complications were more frequent than the previously reported complications of spontaneous abortions or pre-term labor.Citation37 Therefore, current guidelines emphasize prompt diagnosis and operative management as the safest path for both mother and fetus.Citation19,Citation31,Citation35–38

Operative Approach

Pregnant patients must be placed in the left lateral decubitus position to minimize compression on the vena cava.Citation35,Citation39 Compression of the vena cava can cause hypotension by decreasing preload and often affects pregnant women after 20 weeks’ gestation.Citation39,Citation40 Placing a patient into left lateral decubitus position allows gravity and the weight of the gravid uterus to assist with exposure by sweeping the omentum and small bowel away from the appendix.Citation41

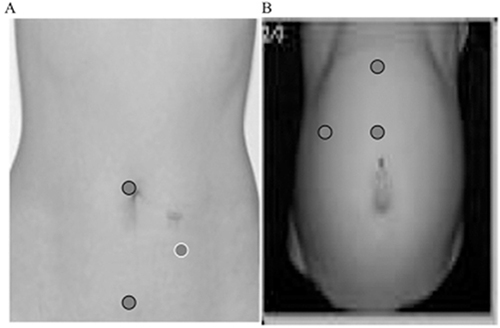

The first step to any laparoscopic operation is port site placement to access the site of surgery (in this case the peritoneal cavity). Fundal height, the distance from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus during pregnancy, must be strongly considered prior to starting the operation.Citation42 Normally, entrance into the abdomen for a laparoscopic appendectomy can be safely done with a Hasson technique or Verres needle. These two techniques can both be used in pregnant patients as well.Citation35 To accommodate the gravid uterus, port placement should be above the palpable fundus and recommendations to adjust the initial access point from the umbilical area to the subcostal region have been made ().Citation35,Citation43 Alternatively, the right subcostal trocar shown in can be placed in the left subcostal position. Studies have shown that surgeons tend to use the Veress needle more in the first trimester, whereas the Hasson technique was frequently preferred during third trimester operations.Citation44 This shift to use of the Hasson is largely due to fear of Veress needle injury to intestine, aorta, or uterus.Citation43 This possibility increases as the uterus becomes larger, more anterior, and causes the intestines to occupy a smaller amount of space anteriorly. If Veress access is chosen, this must be carefully performed away from the gravid uterus. Case reports have been published describing pregnancy loss due to Veress needle injury to uterus causing pneumoamnion.Citation45

Insufflation is an essential step in laparoscopic surgery; however, it must be done with caution in pregnant patients. Insufflation causes increased intraabdominal pressures and diaphragmatic elevation. In pregnant patients, the diaphragm is already elevated, resulting in alterations to the respiratory system. Expiratory reserve volumes and functional residual capacity (FRC) both decrease with pregnancy, while inspiratory capacity increases to maintain total lung capacity.Citation46–48 As a result of reduced FRC, incidence of atelectasis increases.Citation49 Furthermore, respiratory resistance increases while respiratory conductance decreases.Citation47 General guidelines suggest that CO2 insufflation of 10–15 mmHg can be safely used in laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy.Citation35 Although there are case reports and studies implementing pressures greater than 15 mmHg with no increase in adverse effects, the majority of cases are carried out between 10 and 15 mmHg.Citation35

Figure 2 Example trocar placement (indicated by circles) in nonpregnant (A) and pregnant women in the third trimester (B).

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is another important consideration for surgical patients. All patients undergoing surgery and staying in the hospital are at an increased risk of DVTs. This is superimposed on pregnancy being a hypercoagulable state with a 0.1–0.2% risk of DVTs.Citation50 The risk of venous thromboembolism is 5x higher in pregnant patients compared to non-pregnant patients.Citation51,Citation52 Current recommendations for DVT prophylaxis include intraoperative and postoperative pneumatic compression devices, as well as early ambulation.Citation35 There is limited research regarding the use of chemical prophylaxis in pregnant patients, particularly unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin, but heparin can be safely used with monitoring because it does not cross the placenta.Citation52,Citation53 In the event of DVT, warfarin should be avoided because it crosses the placenta and causes embryopathy in first trimester, as well as central nervous system and ophthalmologic abnormalities in any trimester.Citation52

Throughout the operation, it is important to consider the anatomic effects of pregnancy. For example, in a standard laparoscopic appendectomy and in the absence of endometriosis, it is unlikely there would be adhesions to the uterus from inflammatory response. Usually, adhesions are formed to the small bowel and cecum, and blunt dissection, sharp dissection and electrocautery can be used to separate these adhesions.Citation41 In a pregnant patient with a larger uterus, it is not unlikely for there to be adhesions to the uterus. In this case, care must be taken to avoid the gravid uterus with dissection and/or lysis of adhesions. Subsequent steps of the procedure, including creating window in the mesoappendix, division of the mesoappendix, and removal of the appendix, may be more difficult with a larger body habitus and obstruction of view from the gravid uterus. When using a stapler for appendiceal division, articulation is helpful to accommodate the uterus, although case reports have been published documenting successful use of a non-articulating stapler in pregnant patients.Citation54

Lastly, fascial closure is often performed through the largest port site (12 mm), while 5 mm port sites are usually left open and only the skin is closed.Citation55 Since pregnancy is a significant risk factor for hernia formation due to hormonal changes and increased intra-abdominal pressure, fascial closure in large fascial defects is a critical step in this procedure to prevent future complications.Citation56

A retrospective case series published by Machado and Grant analyzed twenty cases with surgery occurring in all three trimesters. Additionally, some cases were performed with Veress needle entry, but most utilized Hasson technique. Three ports were utilized with placement adjustment based on gestational age and uterus position as previously described. These cases used endoloops for ligation of the appendix. In the cases described, antibiotics were only administered for 1 day for non-perforated cases and 2–3 days for phlegmonous appendicitis. Tocolysis (indomethacin 100 mg suppository) was given to 20% of patients for uterine contractility.Citation32 These case reports emphasize the importance of co-management by an obstetric team. All patients had fetal heart rate monitoring before and after surgery. Additionally, the administration of tocolytics was based on recommendations from the obstetric team. Obstetricians can also assist with antibiotic and pain management due to their increased experience managing pregnant patients. This emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary and collaborative health care.

Role of Non-Operative Management

Recently, randomized control trials have evaluated the treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis in non-pregnant patients with antibiotics alone. These studies show success rates as high as 71%. However, these studies also report that over one-third of patients will require an appendectomy within 5 years.Citation57–59 Some even report one-third of patients undergoing an appendectomy within 90 days.Citation57

Studies have provided conflicting conclusions regarding the effectiveness and safety of medical management of appendicitis in pregnant patients. One report suggests antibiotic therapy is a good bridge-to-surgery therapy in remote areas where immediate surgical intervention is not available.Citation60 Another retrospective study over 4 years with over 50 pregnant patients stated that medical management is a safe and feasible option for treatment of acute appendicitis in pregnant patients.Citation61

Although there is evidence showing that antibiotics alone can have a role in the treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy, surgical management remains the preferred choice,Citation62 and it is important to consider the safety of antibiotics in pregnant patients. Most common pathogens involved in appendicitis are gram negative – primarily E. coli.Citation63 Bacteroides fragilis, Klebsiella spp., and Streptococcus spp. are also frequently associated with appendicitis but significantly less often.Citation63,Citation64 These organisms are often susceptible to ampicillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftriaxone, cefepime, amikacin, gentamicin, and imipenem.Citation63 Penicillins, including ampicillin and piperacillin, are the most common antibiotic class used in pregnancy and are generally safe. Penicillins, including ampicillin and piperacillin, are the most common antibiotic class used in pregnancy and are generally safe. Penicillins combined with beta-lactamase inhibitors, like piperacillin-tazobactam, are also safe. Although used less frequently, cephalosporins, carbapenems, monobactams, and cephamycins are all safe to use as well.Citation65

Thoughtful consideration of the possibility of unsuccessful non-operative management must be given in clinical decision-making. Some have expressed concerns of increased risk of fetal loss and premature labor in pregnant patients with peritoneal appendicitis. In acute non-perforated appendicitis, approximately 83.9% of patients give birth at term, 10.7% have preterm labor and 5.4% have an abortion.Citation66,Citation67 The rates of preterm labor and abortion increase in perforated appendicitis – 33.3% and 11%, respectively.Citation66,Citation67 The rate of these adverse effects does not differ between trimesters.Citation66 Since there is large increase in the rate of preterm labor and abortion between non-perforated and perforated appendicitis, there should be careful consideration in opting for medical management and delaying surgical management. The 2020 Jerusalem Appendicitis guidelines and the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery 2022 Rapid Guidelines recommend again treating acute appendicitis non-operatively during pregnancy until further evidence is available and go on to recommend planning laparoscopic appendectomy.Citation14,Citation38

Conclusion

Appendicitis in pregnancy is a clinical condition that can be managed safely and effectively if the surgical team is well educated. It is important to consider alterations to operative procedure when compared to non-pregnant patients. Likewise, it is also important to be cognizant of pre- and post-operative management, including alterations in radiographic diagnostics, changes in laboratory results, and antibiotic selections. Current guidelines published by many national and international organizations emphasise the importance of prompt operative management, with the laparoscopic appendectomy as the surgery of choice. Treating appendicitis in pregnancy is a great example of an opportunity for interdisciplinary care between surgery and OBGYN.

Disclosure

Dr Aurora Pryor reports personal fees from Gore, Medtronic, and Stryker, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- D’Souza N, Nugent K. Appendicitis. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014:1.

- Aptilon Duque G, Mohney S. Appendicitis in pregnancy. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Arnbjörnsson E, Bengmark S. Obstruction of the appendix lumen in relation to pathogenesis of acute appendicitis. Acta Chir Scand. 1983;149(8):789–791.

- Jones MW, Lopez RA, Deppen JG. Appendicitis. In: StatPearls. Disclosure: Richard Lopez Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Disclosure: Jeffrey Deppen Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Treasure Island (FL): Ineligible Companies; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023;2023

- Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910–925. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734

- Moris D, Paulson EK, Pappas TN. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis in adults: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2299–2311. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.20502

- Kave M, Parooie F, Salarzaei M. Pregnancy and appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the clinical use of MRI in diagnosis of appendicitis in pregnant women. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14(1):37. doi:10.1186/s13017-019-0254-1

- Zingone F, Sultan AA, Humes DJ, West J. Risk of acute appendicitis in and around pregnancy: a population-based Cohort Study from England. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):332–337. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000780

- Flum DR, Morris A, Koepsell T, Dellinger EP. Has misdiagnosis of appendicitis decreased over time? A population-based analysis. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1748–1753. doi:10.1001/jama.286.14.1748

- Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;232:1–8.

- Mantoglu B, Gonullu E, Akdeniz Y, et al. Which appendicitis scoring system is most suitable for pregnant patients? A comparison of nine different systems. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(1):34. doi:10.1186/s13017-020-00310-7

- Regar M, Choudhary G, Nogia C, Pipal D, Agrawal A, Srivastava H. Comparison of Alvarado and RIPASA scoring systems in diagnosis of acute appendicitis and correlation with intraoperative and histopathological findings. Int Surg J. 2017;4(5):1755. doi:10.18203/2349-2902.isj20171634

- Ishaq A, Khan MJH, Pishori T, Soomro R, Khan S. Location of appendix in pregnancy: does it change? Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:281–287. doi:10.2147/CEG.S154913

- Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15(1):27. doi:10.1186/s13017-020-00306-3

- Masselli G, Brunelli R, Monti R, et al. Imaging for acute pelvic pain in pregnancy. Insights Imaging. 2014;5(2):165–181. doi:10.1007/s13244-014-0314-8

- Jeffrey RB, Jain KA, Nghiem HV. Sonographic diagnosis of acute appendicitis: interpretive pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(1):55–59. doi:10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273690

- Gilo NB, Amini D, Landy HJ. Appendicitis and cholecystitis in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(4):586–596. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181c11d10

- Katz DS, Klein MA, Ganson G, Hines JJ. Imaging of abdominal pain in pregnancy. Radiol Clin North Amer. 2012;50(1):149–171. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2011.08.001

- Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, Richardson WS, Stefanidis D. Guidelines for the Use of Laparoscopy During Pregnancy - A Sages Publication. Board of Governors of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES);2017.

- Spalluto LB, Woodfield CA, DeBenedectis CM, Lazarus E. MR imaging evaluation of abdominal pain during pregnancy: appendicitis and other nonobstetric causes. Radiographics. 2012;32(2):317–334. doi:10.1148/rg.322115057

- Bulas DMD, Egloff AMD. Benefits and risks of MRI in pregnancy. Seminars Perinatol. 2013;37(5):301–304. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2013.06.005

- Yip YP, Capriotti C, Talagala SL, Yip JW. Effects of MR exposure at 1.5 T on early embryonic development of the chick. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;4(5):742–748. doi:10.1002/jmri.1880040518

- Saunders R. Static magnetic fields: animal studies. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;87(2):225–239. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.09.001

- Brent RL. Protection of the gametes embryo/fetus from prenatal radiation exposure. Health Physics. 2015;108(2):242–274. doi:10.1097/HP.0000000000000235

- Yoon I, Slesinger TL. Radiation exposure in pregnancy. In: StatPearls. Disclosure: Todd Slesinger Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Treasure Island (FL): Ineligible Companies; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023;2023

- Amitai MM, Katorza E, Guranda L, et al. Role of emergency magnetic resonance imaging for the workup of suspected appendicitis in pregnant women. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18(10):600–604.

- Baruch Y, Canetti M, Blecher Y, Yogev Y, Grisaru D, Michaan N. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(23):3929–3934. doi:10.1080/14767058.2019.1592154

- Biondi A, Di Stefano C, Ferrara F, Bellia A, Vacante M, Piazza L. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: a retrospective cohort study assessing outcomes and cost-effectiveness. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11(1):44. doi:10.1186/s13017-016-0102-5

- Nazir A, Farooqi SA, Chaudhary NA, Bhatti HW, Waqar M, Sadiq A. Comparison of open appendectomy and laparoscopic appendectomy in perforated appendicitis. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5105. doi:10.7759/cureus.5105

- Cox TC, Huntington CR, Blair LJ, et al. Laparoscopic appendectomy and cholecystectomy versus open: a study in 1999 pregnant patients. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(2):593–602. doi:10.1007/s00464-015-4244-4

- Korndorffer JR, Fellinger E, Reed W. SAGES guideline for laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(4):757–761. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0632-y

- Machado NO, Grant CS. Laparoscopic appendicectomy in all trimesters of pregnancy. JSLS. 2009;13(3):384–390.

- Agha R, Muir G. Does laparoscopic surgery spell the end of the open surgeon? J R Soc Med. 2003;96(11):544–546. doi:10.1177/014107680309601107

- Velanovich V. Laparoscopic vs open surgery: a preliminary comparison of quality-of-life outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(1):16–21. doi:10.1007/s004649900003

- Yumi H. Prepared by the guidelines committee of the society of American G, Endoscopic S. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and use of laparoscopy for surgical problems during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(4):849–861. doi:10.1007/s00464-008-9758-6

- McKellar DP, Anderson CT, Boynton CJ, Peoples JB. Cholecystectomy during pregnancy without fetal loss. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174(6):465–468.

- Aggenbach L, Zeeman GG, Cantineau AEP, Gordijn SJ, Hofker HS. Impact of appendicitis during pregnancy: no delay in accurate diagnosis and treatment. Int J Surg. 2015;15:84–89. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.01.025

- Adamina M, Andreou A, Arezzo A, et al. EAES rapid guideline: systematic review, meta-analysis, GRADE assessment, and evidence-informed European recommendations on appendicitis in pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(12):8699–8712. doi:10.1007/s00464-022-09625-9

- Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, Mebazaa A. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016;27(2):89–94. doi:10.5830/CVJA-2016-021

- Krywko DM, King KC. Aortocaval Compression Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Disclosure: Kevin King Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Treasure Island (FL): Ineligible Companies; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023; 2023.

- Nguyen A, Lotfollahzadeh S. Appendectomy. In: StatPearlsDisclosure: Saran Lotfollahzadeh Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Treasure Island (FL): Ineligible Companies; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023;2023

- Fundal Height. Cleveland Clinic; 2022; Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/22294-fundal-height. Accessed November 18, 2023.

- Donkervoort S, Boerma D. Suspicion of acute appendicitis in the third trimester of pregnancy: pros and cons of a laparoscopic procedure. JSLS. 2011;15(3):379–383. doi:10.4293/108680811X13125733356837

- Rollins MD, Chan KJ, Price RR. Laparoscopy for appendicitis and cholelithiasis during pregnancy: a new standard of care. Surg Endosc Interventional Techniques. 2004;18(2):237–241. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-8811-8

- Friedman JD, Ramsey PS, Ramin KD, Berry C. Pneumoamnion and pregnancy loss after second-trimester laparoscopic surgery. Obstetrics Gynecol. 2002;99(3):512–513.

- Gilroy RJ, Mangura BT, Lavietes MH. Rib cage and abdominal volume displacements during breathing in pregnancy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137(3):668–672. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.668

- LoMauro A, Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy: physiology masterclass. Breathe. 2015;11(4):297–301. doi:10.1183/20734735.008615

- Weinberger SE, Weiss ST, Cohen WR, Weiss JW, Johnson TS. Pregnancy and the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121(3):559–581. doi:10.1164/arrd.1980.121.3.559

- Grott K, Chauhan S, Dunlap JD. Atelectasis. In: StatPearls. Disclosure: Shaylika Chauhan Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Disclosure: Julie Dunlap Declares No Relevant Financial Relationships with Ineligible Companies. Treasure Island (FL): Ineligible Companies; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023; 2023.

- Melnick DM, Wahl WL, Dalton VK. Management of general surgical problems in the pregnant patient. Am J Surg. 2004;187(2):170–180. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.023

- NIH Consensus Development. Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. . JAMA. 1986;256(6):744–749. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060070028

- Toglia MR, Weg JG. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. New Eng J Med. 1996;335(2):108–114. doi:10.1056/NEJM199607113350207

- Casele HL. The use of unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparins in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(4):895–905. doi:10.1097/01.grf.0000211958.45874.63

- Austin CS, Jaronczyk M. Safe laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnant patient during active labor. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;2021(5):rjab127. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab127

- Gutierrez M, Stuparich M, Behbehani S, Nahas S. Does closure of fascia, type, and location of trocar influence occurrence of port site hernias? A literature review. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(12):5250–5258. doi:10.1007/s00464-020-07826-8

- Danawar NA, Mekaiel A, Raut S, Reddy I, Malik BH. How to treat hernias in pregnant women? Cureus. 2020;12(7):e8959. doi:10.7759/cureus.8959

- Flum DR, Davidson GH, Monsell SE, et al. A randomized trial comparing antibiotics with appendectomy for appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1907–1919.

- Salminen P, Tuominen R, Paajanen H, et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(12):1259–1265. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13201

- Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Lobo DN. Safety and efficacy of antibiotics compared with appendicectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344(apr05 1):e2156. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2156

- Carstens AK, Fensby L, Penninga L. Nonoperative treatment of appendicitis during pregnancy in a remote area. AJP Rep. 2018;8(1):e37–e38. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1620279

- Liu J, Ahmad M, Wu J, et al. Antibiotic is a safe and feasible option for uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy - A retrospective cohort study. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2021;14(2):207–212. doi:10.1111/ases.12851

- Joo JIMD, H-CMDP P, Kim MJMD, BHMDP L. Outcomes of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy. Amer J Med. 2017;130(12):1467–1469. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.046

- Jeon HG, Ju HU, Kim GY, Jeong J, Kim M-H, Jun J-B. Bacteriology and changes in antibiotic susceptibility in adults with community-acquired perforated appendicitis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111144. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111144

- Chen CY, Chen YC, Pu HN, Tsai CH, Chen WT, Lin CH. Bacteriology of acute appendicitis and its implication for the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Surg Infect. 2012;13(6):383–390. doi:10.1089/sur.2011.135

- Bookstaver PB, Bland CM, Griffin B, Stover KR, Eiland LS, McLaughlin M. A review of antibiotic use in pregnancy. Pharmacothe J Human Pharmacol Drug Therapy. 2015;35(11):1052–1062. doi:10.1002/phar.1649

- Mantoglu B, Altintoprak F, Firat N, et al. Reasons for undesirable pregnancy outcomes among women with appendicitis: the experience of a tertiary center. Emerg Med Int. 2020;2020:6039862. doi:10.1155/2020/6039862

- Yoo KC, Park JH, Pak KH, et al. Could laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnant women affect obstetric outcomes? A multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(8):1475–1481. doi:10.1007/s00384-016-2584-8