Abstract

Background

Direct ophthalmoscopy is well-suited for video-based instruction, particularly if the videos enable the student to see what the examiner sees when performing direct ophthalmoscopy. We evaluated the pedagogical effectiveness of instructional YouTube videos on direct ophthalmoscopy by evaluating their content and approach to visualization.

Methods

In order to synthesize main themes and points for direct ophthalmoscopy, we formed a broad panel consisting of a medical student, junior and senior physicians, and took into consideration book chapters targeting medical students and physicians in general. We then systematically searched YouTube. Two authors reviewed eligible videos to assess eligibility and extract data on video statistics, content, and approach to visualization. Correlations between video statistics and contents were investigated using two-tailed Spearman’s correlation.

Results

We screened 7,640 videos, of which 27 were found eligible for this study. Overall, a median of 12 out of 18 points (interquartile range: 8–14 key points) were covered; no videos covered all of the 18 points assessed. We found the most difficulties in the approach to visualization of how to approach the patient and how to examine the fundus. Time spent on fundus examination correlated with the number of views per week (Spearman’s ρ=0.53; P=0.029).

Conclusion

Videos may help overcome the pedagogical issues in teaching direct ophthalmoscopy; however, the few available videos on YouTube fail to address this particular issue adequately. There is a need for high-quality videos that include relevant points, provide realistic visualization of the examiner’s view, and give particular emphasis on fundus examination.

Introduction

Direct ophthalmoscopy is a fast and cheap method for diagnosing life- and sight-threatening conditionsCitation1 that medical students and physicians encounter frequently.Citation2,Citation3 It is taught to medical students, and frontline physicians are expected to be familiar with the skill.Citation4,Citation5 However, reports show that in reality, this skill is performed poorly and avoided due to lack of adequate training and low self-confidence.Citation6,Citation7 Direct ophthalmoscopy may be extremely well-suited for online video-based instruction for two reasons: videos may enable the student to see exactly what the examiner sees, providing realistic images of what to expect, and timely access that enables recall of the technique right before it needs to be performed. YouTube (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) was launched in May 2005 as a user-created video-sharing website and has since gained extreme popularity with presently more than 1 billion users, including medical students and physicians who use it regularly for instructions on clinical skills.Citation8,Citation9 Apart from a few good examples, contents of these instructional videos are reported to be of mediocre or poor quality in important areas such as basic life support,Citation10 physical examination,Citation11 basic clinical skills,Citation12–Citation14 anatomy and physiology,Citation15,Citation16 and surgery.Citation17 Medical students, young physicians, and faculty teaching direct ophthalmoscopy need an overview of what is available and what is needed.

Our aim with this descriptive and exploratory study was to systematically evaluate instructional YouTube videos on direct ophthalmoscopy in terms of content and approach to visualize instructional themes and points.

Methods

We synthesized the main themes and points within themes for direct ophthalmoscopy by reading book chapters targeted to medical students and physicians in generalCitation18–Citation20 and formed a panel consisting of one medical student, two junior physicians, one young ophthalmologist, one senior consultant and research associate professor in medical education and simulation, and one senior consultant and professor in ophthalmology who regularly teaches direct ophthalmoscopy ().

Table 1 Main themes and points within themes for direct ophthalmoscopy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to ensure quality in the selection process and in data extraction.Citation21 We searched YouTube on February 15, 2016 using the search term: “ophthalmoscopy” OR “ophthalmoscope” OR “fundoscopy” OR “fundoscope”. We included videos that gave instructions for direct ophthalmoscopy on human eyes. We did not restrict on upload date, video duration, quality, or rating. For practical reasons, we excluded videos with less than ten views and non-English videos.

All videos were screened based on title and description by one author who excluded obviously irrelevant videos. Two authors reviewed the remaining videos to assess eligibility and extract data. In the case of video duplicates, data were extracted from the copy with most views. We extracted data on the upload date, video duration, highest available streaming quality, number of positive and negative ratings, views, and any details on uploader credentials. We evaluated the content of the included videos by assessing whether themes and points were addressed, and noted the time spent on these key points and the sequence at which these points were presented. We also investigated how the contents of the video were visualized.

Due to the nonparametric nature of our data, continuous values were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Correlations between video statistics and contents were investigated using two-tailed Spearman’s correlation. Number and percentage were reported for categorical values. We used Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for data management and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis, and considered a P-value <0.05 as an indication of statistical significance. Ethical approval and patient consent were not sought for this study, since no patients or participants were involved, and since this study is a review of instructional YouTube videos.

Results

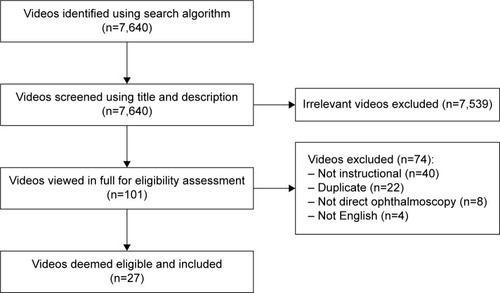

We screened a total of 7,640 videos, of which 101 (1%) were found relevant for detailed eligibility assessment. Of the 101 videos, 74 (73%) were excluded, as 40 (54%) were not instructional (eg, presentation of ophthalmoscopy products), 22 (30%) were duplicates, eight (11%) were not videos of direct ophthalmoscopy, and four (5%) were not in English (). The remaining 27 (27%) videos were included in this study (). Eligible videos were uploaded between May 4, 2007 and October 28, 2015. In total, these videos were viewed 903,105 times. Video statistics with medians, IQRs, and ranges are summarized in . Only eight (30%) videos were of high-definition quality (720p and above) and newer videos were uploaded at a higher quality (ρ=−0.73; P<0.001; Spearman’s correlation). All 27 videos were included in the evaluation of content and visualization. Five of the videos included were originally one video that was separated into five different smaller videos by the uploader, and these five videos were evaluated in combination.

Table 2 YouTube videos included in this study

Table 3 Summary of video statistics based on YouTube data

Video contents

Handling of the ophthalmoscope was included in 17 (74%) videos with a median duration of 66 seconds (IQR: 44–114 seconds) and was presented at the beginning in 16 videos (94%). Optimizing the environment was included in 17 (74%) videos and had a median duration of 10 seconds (IQR: 3–26 seconds). This part was presented at the beginning in six (35%) videos and as the second part in eleven (65%) videos. Approaching the patient was included in all videos with a median duration of 79 seconds (IQR: 55–99 seconds). This was mostly presented as the second (43%) or the third (43%) part of the video. Fundus examination was included in 17 (74%) videos with a median duration of 58 seconds (IQR: 40–94 seconds), and was always presented as the final part of the video. No videos covered all of the 18 points assessed. Overall, a median of 12 points (IQR: 8–14 key points) were covered. Detailed summary is available in . Videos were uploaded by medical schools (n=6), unspecified users (n=6), medical doctors (n=4), ophthalmoscopy distributors (n=3), hospitals (n=2), and university students (n=2). We found a few examples of poor instructions not recommended by experts within the field: one video examined the patient’s left eye with right eye and another video recommended to start fundus examination by examining the macula. We found a significant correlation between the time spent on reviewing fundus examination and views per week, but not total views, indicating that the popularity of the video may be more due to the video reviewing fundus examination than the video being popular because of longer exposure time on YouTube ().

Table 4 Themes and points on direct ophthalmoscopy included in YouTube videos

Table 5 Correlations between the time spent on different themes on direct ophthalmoscopy and YouTube video statistics

Content visualization

Handling of the ophthalmoscope was demonstrated as seen by the examiner in 15 videos (88%) and not demonstrated in one video (6%). In one video (6%), the viewer could only see the effect of adjusting the ophthalmoscope on the light projected, but without seeing how the ophthalmoscope was actually handled. Optimizing the environment was demonstrated as seen by the examiner in ten videos (41%) and not demonstrated in six videos (35%).

We found most difficulties in video demonstration of how to approach the patient and how to examine the fundus. Approaching the patient was demonstrated as seen by the examiner in two videos (9%) and not demonstrated in one video (4%). The remaining 20 videos (87%) were seen from a bystander’s point of view in which one would see the examiner get closer to the patient without seeing what the examiner actually sees through the ophthalmoscope. Three of these videos compensated for this by including a picture of what the red reflex looks like. Fundus examination was demonstrated as seen by the examiner in four videos (22%), of which two were an approximation achieved by using a fundus photograph but limiting the visible field to a small circular area. Fundus examination was not demonstrated at all in four videos (22%). In the remaining ten videos (56%), a fundus photograph was shown without limiting the visible field.

Discussion

One of the fundamental problems in teaching direct ophthalmoscopy is that the student cannot see what the teacher sees in the direct ophthalmoscope and vice versa.Citation1 Hence, it is difficult to both show what it looks like when the teacher performs the skill correctly and to give relevant feedback to the student. Therefore, it seems that direct ophthalmoscopy may be well-suited for video-based instruction, particularly if videos enable the student to see what the examiner sees when performing direct ophthalmoscopy. This study showed that the number of instructional videos on direct ophthalmoscopy is small with varying content and that the possibilities of video instruction were not utilized in such a way that the examiner’s view was realistically visualized. Also, we found that more time spent on fundus examination correlated with more views per week, which may suggest that this part is of particular interest to the viewers.

There is an ongoing discussion on whether or not direct ophthalmoscopy should be a part of the pregraduate medical curriculum and be expected as a skill every physician should be proficient in.Citation22,Citation23 Eye disorders are a common cause for medical attention in the primary sector and their prevalence is only expected to increase with an increasing elderly population.Citation2,Citation3,Citation24 An incorrect or delayed diagnosis can result in otherwise preventable loss of vision, which impacts the patient’s ability to drive, work, and function in general.Citation25,Citation26 While these facts pull in the direction of keeping direct ophthalmoscopy in the curriculum, some argue that the general proficiency in direct ophthalmoscopy is poor, which by itself may lead to an incorrect or delayed diagnosis.Citation23 We believe that improvements in educational initiatives are yet to be explored and that better Internet resources including YouTube videos, innovative instructional methods,Citation27–Citation30 and evidence-based simulation trainingCitation30,Citation31 may contribute to optimizing training in direct ophthalmoscopy in the future.

Internet resources are of variable quality, as anyone with or without credentials can contribute.Citation32,Citation33 We found a few poor examples in YouTube videos of direct ophthalmoscopy. Such examples of poor videos have also been demonstrated in, for example, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and lumbar puncture, which may lead to severe consequences on the patients.Citation10,Citation34 How best to navigate as a clinical instructor with these types of resources is a matter of ongoing discussion.Citation32,Citation33 One solution is that the clinical instructor develops his/her own educational videos or distributes selected quality-verified educational material through their own developed apps to achieve higher quality when the users access these materials on-the-go.Citation35–Citation38

A plethora of studies exist on how to implement Internet technologies for medical education and they show that it may be feasible on many occasions, but paucity remains when it comes to studies on why and when it works.Citation39 Mayer and Moreno lay the ground work for the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, which is a framework for understanding multimedia-assisted learning from the learner’s perspective.Citation40 According to the theory, images and sounds are channeled into the working memory, which then integrates and organizes information for short- and long-term memory.Citation40 Mayer also suggested that the capacity of this system is limited and that learning outcome may depend on the presentation because learners can be overloaded with irrelevant details.Citation41 For example, highlighting essential material, eliminating extraneous material, and presenting words and pictures in combination rather than as words alone are all shown to significantly benefit learning.Citation41 Our experience and findings of this study indicate that the available YouTube videos on direct ophthalmoscopy were not designed with these considerations in mind, which if otherwise could provide an important improvement to the learning experience that suffers from a nonvisual instructive nature of a procedure that is fundamentally visual. When designing instructional videos on direct ophthalmoscopy, we suggest the inclusion of the spectrum of relevant points (), realistic visualization of what the procedure actually looks like from the examiner’s view, and giving particular emphasis on how to examine the fundus, which we find is correlated with video popularity since this may reflect what the users are demanding. Also, we suggest that Mayer’s findingsCitation41 on how to optimize the pedagogical effectiveness by considering the design of the instructional videos, for example, highlighting essential material, eliminating extraneous material, and presenting words and pictures in combination, are considered when designing these videos, as these considerations may further improve the instructional value.

How best to utilize video instruction of clinical procedures and their role in timely learning in clinical practice is a field yet to be fully explored. One study found that medical students could perform volar splinting better and faster when they had timely access to an instructional video.Citation42 Another study found that medical students and resident physicians performed better at chest tube insertion when they could use a mobile device for timely access to an instructional video.Citation43 Exploratory studies have looked into how this knowledge is appreciated and suggest that timely access to instructional videos cannot stand alone, but rather augment the overall learning experience.Citation44,Citation45 Learning technical skills may need hands-on experience and relevant feedback, which requires on-site teaching on patients or simulation training.

Strengths and limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting our findings. One strength is the inclusion of a panel representing a broad range of expertise levels, which enabled different views on the matter. Another strength is our systematic approach to inclusion of videos and extraction of data. Inter-rater agreement of our evaluations was 0.95 for evaluating themes and points and 0.87 for the sequence of presentation (Cohen’s kappa), which demonstrates good consistency. We have experienced that systematic searches on YouTube yield a very large number of hits with videos that are irrelevant, which is also reflected by the low number of eligible videos (1%) obtained from the screening process. An important limitation is that we only assessed videos with ten views or more and in English for practical reasons and to provide results that are relevant for a broad community. However, this approach may miss videos that are released very recently or the videos that may be well-designed but are not popular for other reasons. Videos may lack important content or may be designed poorly, but still serve their purpose. Another important limitation of our study design is that we did not investigate the learning effect of the included videos and, therefore, cannot say whether these videos actually work well in practice.

In conclusion, videos may help overcome the pedagogical issues in teaching direct ophthalmoscopy, but current videos on YouTube fail to address this particular issue adequately. There is a need for high-quality videos that fully utilize the possibilities of video as an instructional tool ().

Table 6 Suggestions for videos instructing in direct ophthalmoscopy

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the University of Copenhagen fund “Undervisningskvalitetspuljen”, which is dedicated for initiatives in education quality. Author Nanna Jo Borgersen has received a scholarship grant from Novo Nordisk Foundation to conduct research in direct ophthalmoscopy simulation. The funding bodies had no influence on the design of the study, analysis of data, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- YusufIYangEKnightKLeaverLDirect ophthalmoscopy: teaching in primary careClin Teach201613323523725982427

- SheldrickJHWilsonADVernonSASheldrickCMManagement of ophthalmic disease in general practiceBr J Gen Pract1993433764594628292417

- SheldrickJHVernonSAWilsonAReadSJDemand incidence and episode rates of ophthalmic disease in a defined urban populationBMJ199230568599339361458075

- BaylisOMurrayPIDayanMUndergraduate ophthalmology education – A survey of UK medical schoolsMed Teach201133646847121355698

- BenbassatJPolakBCJavittJCObjectives of teaching direct ophthalmoscopy to medical studentsActa Ophthalmol201290650350722040169

- BruceBBLamirelCWrightDWNonmydriatic ocular fundus photography in the emergency departmentN Engl J Med2011364438738921268749

- GuptaRRLamWCMedical students’ self-confidence in performing direct ophthalmoscopy in clinical trainingCan J Ophthalmol200641216917416767203

- SchmidtTInformal education of medical doctors on the InternetStud Health Technol Inform2013190929423823386

- New data on physicians, search & Youtube [homepage on the Internet]ChicagoSiren Interactive [cited March 8, 2016]. Available from: https://www.sireninteractive.com/sirensong/new-data-on-physicians-search-youtube/Accessed April 28, 2016

- BeydilliHSerinkenMEkenCThe Validity of YouTube Videos on Pediatric BLS and CPRTelemed J E Health2016222165169

- AzerSAAlgrainHAAlKhelaifRAAlEshaiwiSMEvaluation of the educational value of YouTube videos about physical examination of the cardiovascular and respiratory systemsJ Med Internet Res20131511e24124225171

- LaroucheMGeoffrionRLazareDMid-urethral slings on YouTube: quality information on the internet?Int Urogynecol J Epub2015129

- DuncanIYarwood-RossLHaighCYouTube as a source of clinical skills educationNurse Educ Today201333121576158023332710

- NasonGJKellyPKellyMEYouTube as an educational tool regarding male urethral catheterizationScand J Urol201549218919225363608

- AzerSACan “YouTube” help students in learning surface anatomy?Surg Radiol Anat201234546546822278703

- RabeeRNajimMSherwaniYYouTube in medical education: a student’s perspectiveMed Educ Online2015202950726384480

- LeeJSSeoHSHongTHYouTube as a potential training method for laparoscopic cholecystectomyAnn Surg Treat Res2015892929726236699

- SchneidermanHChapter 117: The funduscopic examinationWalkerHKHallWDHurstJWClinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations3rd edBostonButterworths1990

- ThomasJMonaghanTOxford Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills2nd edOxfordOxford University Press2014

- SubhiYSkou ThomsenASOftalmoskopi [Ophthalmoscopy]GjaerdeLISubhiYKongeLProcedurebogen [Book of Clinical Procedures]1st edCopenhagenMunksgaard2014 Danish

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; the PRISMA statementBMJ2009339b253519622551

- YusufIHSalmonJFPatelCKDirect ophthalmoscopy should be taught to undergraduate medical students-yesEye (Lond)201529898798926043702

- PurbrickRMChongNVDirect ophthalmoscopy should be taught to undergraduate medical students – NoEye (Lond)201529899099126043708

- WongWLSuXLiXGlobal prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet Glob Health201422e106e11625104651

- RasmussenABrandiSFuchsJVisual outcomes in relation to time to treatment in neovascular age-related macular degenerationActa Ophthalmol201593761662026073051

- SubhiYHenningsenGØLarsenCTSørensenMSSørensenTLFoveal morphology affects self-perceived visual function and treatment response in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a cohort studyPLoS One201493e9122724618706

- MackayDDGarzaPSOcular fundus photography as an educational toolSemin Neurol201535549650526444395

- MilaniBYMajdiMGreenWThe use of peer optic nerve photographs for teaching direct ophthalmoscopyOphthalmology2013120476176523246117

- KrohnJKjersemBHøvdingGMatching fundus photographs of classmates. An informal competition to promote learning and practice of direct ophthalmoscopy among medical studentsJ Vis Commun Med2014371–2131824694281

- KellyLPGarzaPSBruceBBGraubartEBNewmanNJBiousseVTeaching ophthalmoscopy to medical students (the TOTeMS study)Am J Ophthalmol201315651056106124041982

- ThomsenASSubhiYKiilgaardJFla CourMKongeLUpdate on simulation-based surgical training and assessment in ophthalmology: a systematic reviewOphthalmology201512261111113025864793

- SubhiYBubeSHRolskov BojsenSSkou ThomsenASKongeLExpert involvement and adherence to medical evidence in medical mobile phone apps: a systematic reviewJMIR Mhealth Uhealth201533e7926215371

- EysenbachGPowellJKussOSaEREmpirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic reviewJAMA2002287202691270012020305

- RösslerBLahnerDSchebestaKChiariAPlöchlWMedical information on the Internet: Quality assessment of lumbar puncture and neuroaxial block techniques on YouTubeClin Neurol Neurosurg2012114665565822310998

- FossKTSubhiYAagaardRDeveloping an emergency ultrasound app – a collaborative project between clinicians from different universitiesScand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med2015234726092581

- SubhiYFossKTHenriksenMJVTodsenTUdvikling og brug af web-baserede apps [Development and use of web-based apps]Tidsskr Læring og Medier201471212 In Danish

- SubhiYTodsenTRingstedCKongeLDesigning web-apps for smartphones can be easy as making slideshow presentationsBMC Res Notes201479424552200

- ZhangMWTsangTCheowEHoCShYeongNBHoRCEnabling psychiatrists to be mobile phone app developers: insights into app development methodologiesJMIR Mhealth Uhealth201424e5325486985

- CookDAHatalaRBrydgesRTechnology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysisJAMA2011306997898821900138

- MayerRMorenoRNine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learningEducational Psychologist20033814352

- MayerREApplying the science of learning to medical educationMed Educ201044654354920604850

- ChengYTLiuDRWangVJTeaching splinting techniques using a just-in-time training instructional videoPediatr Emerg Care Epub201541

- DavisJSGarciaGDWyckoffMMUse of mobile learning module improves skills in chest tube insertionJ Surg Res20121771212622487392

- HardymanWBullockABrownACarter-IngramSStaceyMMobile technology supporting trainee doctors’ workplace learning and patient care: an evaluationBMC Med Educ201313623336964

- KamdarGKesslerDOTiltLQualitative evaluation of just-in-time simulation-based learning: the learners’ perspectiveSimul Healthc201381434823299050