Abstract

Background

Orbital exenteration (OE) is a disfiguring procedure most commonly performed for locally advanced and potentially life-threatening periorbital malignancies.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed records of 11 consecutive HIV patients who underwent OE for invasive orbital malignancy at our institution from January 2005 to December 2015. Patient demographic and clinic data and histopathology of the tumor were analyzed.

Results

There were eight (72.72%) female and three (27.28%) male participants ranging in age from 31 to 52 years with an mean of 39.4 years. Nine patients had been known to be HIV-positive for at least 2 years, and HIV-positive status was revealed at presentation for two patients. The mean CD4 cell count was 154.4 cells/mm3. Histopathological examination showed invasive orbital squamous cell carcinomas in nine patients (81.81%), achromic orbital melanoma in one patient (9.09%), and adenoid cystic carcinoma in one patient (9.09%). None of the patients underwent primary orbital reconstruction. The mean follow-up time was 3.4 months. Only one patient who underwent adjuvant radiotherapy was seen after 12 months.

Conclusion

Oculo-orbital malignancies are very aggressive in HIV-positive individuals, especially in untreated patients. Routine screening for suspected ocular surface lesions and early surgical removal of all these lesions could help to avoid the need to perform the radical and disfiguring OE procedure.

Introduction

Orbital exenteration (OE) is a disfiguring procedure that typically involves removal of the entire contents of the orbit, including the periorbital, appendages, eyelids, and sometimes a varying amount of surrounding skin and bone.Citation1 This procedure is indicated for the treatment of potential life-threatening malignancies arising from the orbit, para nasal sinuses, or periocular skin.Citation2,Citation3 Orbital malignancy can also be a metastasis of other cancers.Citation4 Patients with HIV infection are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and some nonAIDS-related cancers than patients in the general population.Citation5 To date, no research on OE has been conducted in Central Africa, despite the high prevalence of HIV infection and HIV-related ocular tumors. This study aimed to present the clinical features, the histological diagnosis, and the management of invasive orbital tumors in HIV-infected individuals in our hospital.

Patients and methods

Medical records of 11 HIV patients exenterated between January 2005 and December 2015 at the University Teaching Hospital of Yaounde were analyzed. Written informed consent for the procedure and for use of patient data for scientific purposes was obtained from all the patients after explaining the nature of the procedure. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Comite institutionnel d’ethique de la recherché du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Yaounde). The procedure was performed under general anesthesia. All the patients received intravenous Ceftriaxone prior to the surgery. Histological examination of specimens was done in the central laboratory of the University Teaching Hospital of Yaounde. After discharge, the patients were regularly screened for recurrences until spontaneous healing of the orbital cavity. Those requiring adjuvant therapy were referred to the General Hospital. Demographics (age, gender, and residency), clinical measurements (visual acuity, CD4 cell count at surgery, and histological results), orbital reconstruction, postoperative complications, and follow-up length were analyzed. Exenteration was classified according to the classification proposed by Meyer and Zaoli (1971).Citation6 Exclusion criteria were orbital bony destruction and cerebral extension of the tumor. One-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare CD4 count and Cameroon CD4 count guidelines.

Results

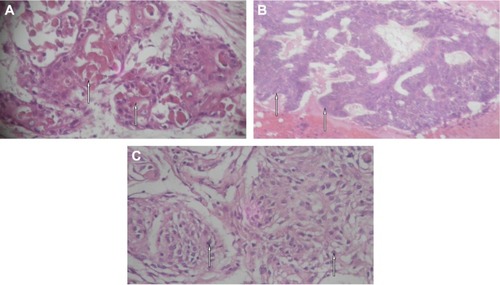

Between January 2005 and December 2015, 11 consecutive HIV patients underwent OE in our hospital, given a rate of 1.10 OEs per year. The baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and histological results of our patients are summarized in . Participant’s age ranged from 31 to 52 years with an average of 39.4 years. There were eight (72.72%) female and three (27.28%) male participants. Most of the patients originated from South-West Region (45.45%). All the patients attended another eye clinic before presenting to our hospital. Six patients reported that they underwent surgery for eyelid tumor 2 years before. All the patients had used various medicines and specifically traditional eye medicines (TEMs) before reporting to our hospital. Protrusion of orbital contents and globe displacement were the presenting features in all patients (). Visual acuity was no light perception in all cases. Seven patients knew that they were HIV-positive for at least 2 years and were not on highly active antiretro-viral therapy (HAART). Positive HIV status was revealed at presentation for four patients. All the patients had CD4 count significantly well below 350 cells/mm3 (P=0.022). Computed tomography (CT) of the orbits showed orbital invasion without orbital bony destruction (). Histological examinations revealed nine invasive orbital squamous cell carcinomas (81.81%; ), one adenoid cystic carcinoma (9.09%; ), and one achromic orbital melanoma (9.09%; ). None of the patients underwent primary orbital reconstruction. All of them were referred for adjuvant treatment and for HAART. The mean follow-up time was 4.2 months (range 1–12 months). Only one patient who underwent adjuvant radiotherapy was seen after 12 months (). Six patients were lost to follow-up before 3 months, and five patients were reported to be deceased.

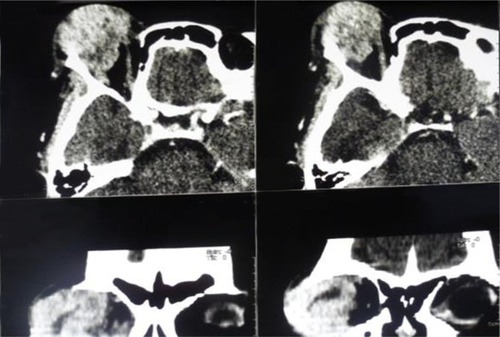

Figure 2 CT scan of the orbits.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography.

Figure 3 Histological examination (magnification ×40).

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included in this study

Discussion

Malignant tumors of the orbit are relatively rare. Exenteration is the only therapeutic option in case of advanced orbital tumors. Although it is disfiguring, this procedure aims to improve the quality of life of the patient.Citation7 In our study, all the patients presented with a painful orbital tumor, and exenteration was indicated at the first consultation. The mean age of 39.4 years reported in our study correlates with the mean age among HIV-positive individuals in Africa.Citation8 Dandala et al showed a significant association between a young patient with ocular surface squamous neoplasia and HIV status.Citation9 In our study, the mean CD4+ cell count was low as none of our patients were on HAART. This indicates that all the included patients were significantly immunosuppressed at presentation. A low CD4+ cell count and other immunosuppressive states like diabetes and intravenous drug abuse are predisposing factors for orbital involvement with malignancies in AIDS.Citation10 All the patients reported to our hospital at an advanced stage of their illness, and OE was the only therapeutic option. Preoperatively, an orbital CT scan revealed no bony destruction and no intracranial invasion in all the patients. Orbital imaging using CT and magnetic resonance imaging give the exact characteristics of the tumor extension and structures involved.Citation11

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma was the most encountered malignant tumor leading to OE in our series. Similar results were found in Ghana by Ackuaku-Dogbe.Citation1 Several risk factors for the development of this ocular surface neoplasm including solar radiation, melanoderma, and high prevalence of HIVCitation12 are present in Cameroon. Squamous cell carcinoma is highly aggressive, with a higher incidence of corneal, sclera, and orbital invasion when associated with HIV infection.Citation13 At an early stage, incisional biopsy with 4 mm margin clearance and antimetabolite application is the treatment of choice.Citation14 Socio-cultural beliefs (ie, confidence in TEM), the aggressive nature of the tumor due to HIV infection, and in some cases the mismanagement of suspected lesions of the ocular surface could explain why our patients presented with advanced invasive orbital tumors.

One patient with a previously treated eyelid tumor developed orbital adenoid cystic carcinoma and was exenterated. Orbital adenoid cystic carcinoma is one of the most severe malignant tumors in the orbit, originating from the palpebral portion of the lacrimal gland. It has a high local recurrence rate and low survival rate.Citation15 Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the eyelid usually mimics chalazion and may easily be overlooked.Citation16 This malignant tumor usually grows slowly; the mean symptom duration is ~10 years, and mean age of patients at the time of detection is 59 years.Citation17 Considering the patient’s age (31 years), the low CD4 cell count (94 cells/mm3), and the speed of tumor development, it is hypothesized that immune status may have contributed to the aggressive advancement of adenoid cystic carcinoma in our patient.

Ocular melanomas are a rare but potentially devastating malignancy arising from the melanocytes of the uveal tract, conjunctiva, or orbit. The first case of ocular melanoma in a patient with HIV infection was reported by Abramson et al in 1996.Citation18 The age of presentation of conjunctival melanoma is usually in the fifth decade.Citation19 The patient who presented with an achromic orbital melanoma in our series was followed-up for 2 months.

Several different methods for orbital reconstruction have been described, including the use of midline forehead flaps, temporalis muscle transposition, dermal grafts, dermis fat grafts, and split skin grafts.Citation1,Citation18 Although primary reconstruction provides a better postoperative esthetic appearance, early recurrences can be missed. In our study, no primary orbital reconstruction was performed. Spontaneous healing of the orbital cavity was our preference (). This approach favors the early diagnosis of recurrences. As all orbital tumors found in our study tended to form distant metastases, all the patients were referred for a metastasis check and for adequate additional radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are the high dropout rate from follow-up and the limited sample. Only one patient who underwent successful adjuvant radiotherapy attended the hospital 12 months after the surgery. This can be explained by the discouragement of disfiguring patients, the cost and travel distance, and sometimes the death of the patient. The overall prognosis for patients who undergo OE for malignancy remains poor. Management of these patients should be multidisciplinary, involving all other appropriate specialties to optimize the outcomes for this vulnerable patient group.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that oculo-orbital malignancies are very aggressive in HIV-positive individuals, especially in untreated patients. Exenteration was performed for quality of life purposes rather than long-term survival. Preventive measures including routine screening for suspected ocular surface lesions, early surgical removal, and histopathologic diagnosis of all ocular lesions should be implemented as part of care of patients with HIV infection. Adequate counseling of patients, parents, and caregivers will help to secure better follow-up for recurrence assessment.

Author contributions

KG, YB, and BAL contributed to the study design, analyzed the data, and performed critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. KG, NA, and NC performed the surgery and were responsible for the clinical management of the patients. KG, NC, and BAL wrote the paper. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, read and approved the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Ackuaku-DogbeEReview of orbital exenterations in Korle-Bu Teaching HospitalGhana Med J2011452454921857720

- NassabRSThomasSSMurrayDOrbital exenteration for advanced periorbital skin cancers: 20 years experienceJ Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg2007601011031109

- KennedyREIndications and surgical techniques for orbital exenterationAdv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg199291631731457059

- LachkhemAKhamassiKBen HamoudaRLes cancers de l’orbite et ude retrospective à propos de 31 casJ Tunis ORL Chir Cervico-Faciale20101912932

- BolducPRoderNColgateECheesemanSHCare of patients with HIV infection: primary careFP Essent2016443314227092565

- YeattsRPThe esthetics of orbital exenterationAm J Ophthalmol2005139115215315652840

- MaheshwariRReview of orbital exenteration from an eye care centre in Western IndiaOrbit Amst Neth20102913538

- KharsanyABMKarimQAHIV infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: current status, challenges and opportunitiesOpen AIDS J201610344827347270

- DandalaPPMalladiPKavithanullOcular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN): a retrospective studyJ Clin Diagn Res2015911NC10NC13

- SodhiPKOrbital manifestations in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndromeNepal J Ophthalmol20146220521925680251

- Ben SimonGJSchwarczRMDouglasRFiaschettiDMcCannJDGoldbergRAOrbital exenteration: one size does not fit allAm J Ophthalmol20051391111715652823

- MasanganiseRMagavaAOrbital exenterations and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva at Sekuru Kaguvi Eye Unit, ZimbabweCent Afr J Med200147819619912808766

- KamalSKalikiSMishraDKBatraJNaikMNOcular surface squamous neoplasia in 200 patients: a case-control study of immunosuppression resulting from human immunodeficiency virus versus immunocompetencyOphthalmology201512281688169426050538

- MaurielloJANapolitanoJMcLeanIActinic keratosis and dysplasia of the conjunctiva: a clinicopathological study of 45 casesCan J Ophthalmol19953063123168574978

- LinTHeYZhangHSongGTangDZhaoHAnalysis of treatment and prognosis of orbital adenoid cystic carcinomaZhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi2009454309313 Chinese19575961

- KatoNYasukawaKOnozukaTPrimary cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma with lymph node metastasisAm J Dermatopathol19982065715779855352

- CacchiCPersechinoSFidanzaLBartolazziAA primary cutaneous adenoid-cystic carcinoma in a young woman. Differential diagnosis and clinical implicationsRare Tumors201131e321464876

- AbramsonDHServodidioCAOcular melanoma and human immunodeficiency virus infectionInsight Am Soc Ophthalmic Regist Nurses19962138688

- HowardDJLundVJWeiWICraniofacial resection for tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a 25-year experienceHead Neck2006281086787316823871