Abstract

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome typically affects young, healthy individuals. Despite the dramatic fundus appearance seen in this syndrome, these patients are usually asymptomatic. The syndrome includes peculiar vascular abnormalities in the form of multiple aneurysmal dilatations seen along retinal arterioles and optic nerve-head arterioles, which are best appreciated on fluorescein angiography. Neuroretinitis and retinal vasculitis are seen in all patients, and manifested by staining of the optic nerve head and diffuse leakage from vessels, mainly arterioles, on fluorescein angiography. The devastating vision-threatening outcomes of this syndrome include exudative retinopathy and extensive peripheral retinal nonperfusion areas, which can eventually lead to neovascularization. This review summarizes current knowledge on the variable clinical aspects of this disease, highlighting diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Introduction

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome is a rare clinical entity of unknown etiology.Citation1–Citation3 Inflammation of the retinal vessels is seen in association with various ocular inflammations and systemic vascular diseases, or it can be idiopathic. The phlebitis is usually more common than the arteritis.Citation4,Citation5 Arterial involvement is a common finding in cases of IRVAN, which is associated with multiple aneurysmal dilatations of the retinal and optic nerve-head arterioles.Citation1–Citation3 These peculiar vascular anomalies measure 75–300 µm in diameter, and are present at or near major branching sites on retinal arterioles.Citation2 Other features include peripheral capillary nonperfusion, retinal neovascularization, and macular exudation, which leads us to believe that this disease, which was once thought to be a benign self-limiting condition, is not so, and could lead to severe vision-threatening complications if not treated in time.Citation1–Citation3

This syndrome typically affects young, healthy individuals and has a female preponderance.Citation2,Citation3 It usually has no systemic association, but reports recently have found it to be associated with allergic and hypersensitivity vasculitis, and thus systemic evaluation in IRVAN could be tailored according to their review of systems.Citation2,Citation6 Various therapeutic regimens have been advocated for treatment of IRVAN, such as panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), surgery, transscleral cryotherapy, corticosteroid therapy, administration of monoclonal antibodies, such as ranibizumab, and immunomodulatory therapy. The disease has variable clinical presentation, and clinical diagnosis is aided by the help of ophthalmic imaging, such as fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), preferably by wide-field system and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Patients usually present asymptomatically, but close, careful follow-up is essential.

Historical aspects and epidemiology

Karel et alCitation4 described FA findings in a series of children with uveitis. In one of these children, he noted FFA evidence of vasculitis and saccular and fusiform aneurysms of the principal arterial branches along the optic disk and peripapillary area in a 19-year-old girl. Jampol et alCitation6 described features of bilateral retinal arteritis with few subtle arterial irregularities, similar to features of IRVAN and with inactive pulmonary disease and a positive purified protein derivative. Kincaid and SchatzCitation1 described this syndrome in greater detail, and reported findings in two patients. Both were young patients, and neither revealed any associated systemic findings. One patient was treated with oral steroids unsuccessfully.

Owens and GregorCitation7 described a case of vanishing retinal arterial aneurysms, in which they noticed retinal vasculitis and multiple retinal arterial aneurysms in an 18-year-old girl, which gradually decreased in size and number over time. Chang et alCitation2 proposed the acronym “IRVAN” to highlight the features of this condition. They described ocular features in ten patients. The most common findings were numerous aneurysmal dilatations of the optic nerve head and retinal arterioles in their series, and they advocated routine FFA to identify same. They also noted uveitis to be an associated feature. The most common vision-threatening manifestation was exudative retinopathy and peripheral capillary nonperfusion, and they advocated prompt and aggressive treatment in the form of PRP in progressive neovascularization. Samuel et alCitation3 conducted the largest cohort study of IRVAN, and proposed functional staging to improve treatment paradigms. They studied 44 eyes of 22 patients, and advocated PRP in cases of widespread retinal nonperfusion and before or shortly after the development of neovascularization.

Pathogenesis

Vasculitis is a clinicopathological process characterized by inflammation and necrosis of the blood vessels. In some diseases, vasculitis maybe a major feature, whereas in others it occurs as a secondary phenomenon.Citation4,Citation8 Vessels of any size and organ may be affected, and an association, either direct or indirect, can be established with immunopathogenic mechanisms and immunocomplex mediation. The theory of deposition in immunocomplex mediation has been shown in animal models as well. Inflammation of the retinal vessels can occur in association with various ocular inflammations and vascular diseases or it can be idiopathic. Most often in vasculitis, phlebitis predominates, and arterial involvement is usually a rare phenomenon.Citation9 On histopathological examination, immunopathological response is shown to cause fibrinoid thrombosis in arteries, but without a cellular response. Ocular hypoxia, however, may cause a cellular response in the anterior chamber, which resembles iritis.Citation10 Secondary retinal changes include macroaneurysm formation, neovascularization, collateral vessel formation, and capillary nonperfusion.

Retinal arteritis is a specific entity characterized by retinal arterial occlusions in which the immunopathogenic mechanism plays a major role.Citation9 It may involve immunocomplex deposition and the development of antibodies. This condition maybe idiopathic or associated with proven autoimmune diseases, eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, Goodpasture’s syndrome, Loeffler’s syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg–Struss syndrome and cryoglobulinemia.Citation9,Citation11,Citation12

The retinal arteries, unlike the other small arteries of the body, lacks the elastic lamina; otherwise, its composition is similar to vessels of equal caliber elsewhere in the body. At proximity to the disk, the media of retinal arteries contains five to seven layers of smooth-muscle cells, and beyond the equator the retinal arteries become arterioles, with only one to two layers of smooth-muscle cells. The retinal veins have three to four smooth-muscle layers at the disk, which are replaced by fibroblasts within a short distance from the disk.Citation13 Inflammation primarily involving the smooth-muscle cells layers of the arterial walls could explain the preferential arterial involvement and paucity of venous changes in cases of IRVAN. Focal loss of smooth-muscle cells could lead to weakening of the arterial wall and aneurysmal dilatation, while intimal desquamation and proliferation could lead to arterial narrowing and leakage. Retinal aneurysmal dilatations may be acquired in elderly people with sarcoidosis and hypertension,Citation14 seen in Coat’s disease and Leber’s miliary aneurysms, or be associated with mitral valve prolapse.Citation15–Citation17 The mechanism for aneurysmal dilatation formation remains focal partial damage, which can lead to arterial ectasias by the same mechanism, particularly in the presence of raised intra-arterial pressure, especially in the elderly with sarcoidosis.Citation14 Hypertension possibly plays a role in the formation of arterial ectasias by increasing the transmural pressure at the level of the weakened inflamed arterial wall. There are extensive dynamics in the location, shape, and size of aneurysms in a patient with IRVAN, which could be explained by a possible migratory process involving alternate segments along the vascular tree.Citation18 The affected segment may weaken to a point at which under the influence of intravascular hydrostatic pressure, it dilates and acquires the typical fusiform appearance, and further weakening could lead the ectasias to attain a more saccular appearance. With resolution of inflammation within the involved segment, the strength of the vascular tree may be regained, which could lead to complete restoration of the vessel’s normal contour. If there is no resolution of the lesions, it may represent more severely and irreversibly damaged wall segments.Citation18

Neuroretinitis, the other associated feature in IRVAN, is a type of optic neuropathy characterized by acute unilateral visual loss in the setting of optic disk swelling, which is accompanied by hard exudates characteristically arranged in a star shape around the fovea. The pathogenesis of neuroretinitis is associated with direct involvement of the optic nerve fibers by infectious or inflammatory processes, leading to edema and fluid exudation from the inflamed cellular area of the peripapillary retina. When optic disk swelling and macular stars are associated with focal or multifocal inflammatory lesions in the retina (retinitis), especially if an infectious cause is documented, the term “neuroretinitis” is preferred.Citation19

Vascular dilatation is thought to arise secondarily to inflammatory processes in the retinal artery walls. Both retinal and the choroidal vessels can be damaged in this disorder, which can mimic a number of inflammatory and infectious diseases.Citation6,Citation9,Citation10 Exudative maculopathy and retinal neovascularization are mainly responsible for decreased visual acuity and sight-threatening complications of IRVAN, which are due to leakage from dilated vessels and peripheral capillary closure, along with a possible role of VEGF.Citation1–Citation3 Patients with IRVAN suffer in part from a retinal microvascular disease process, similar to other clinical entities that progress to retinal neovascularization, such as diabetic retinopathy.Citation20 However, some time is required before sufficient nonperfusion develops and leads to the development of neovascularization. TNFα might be a causative factor in mediating inflammation and causing tissue destruction in IRVAN patients. Cheema et alCitation21 showed improvement in two patients treated with infliximab, an anti-TNF.

Classification and clinical features

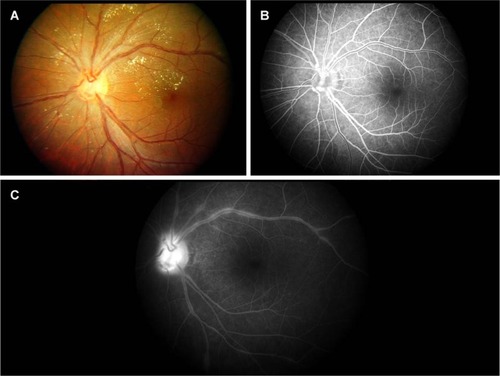

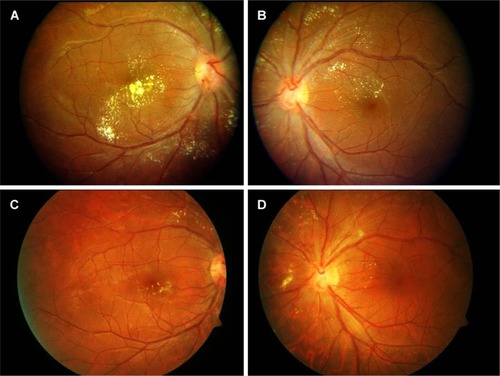

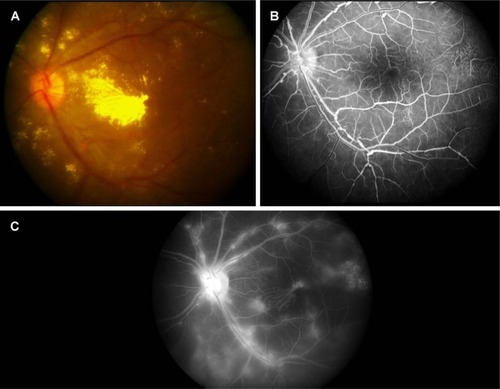

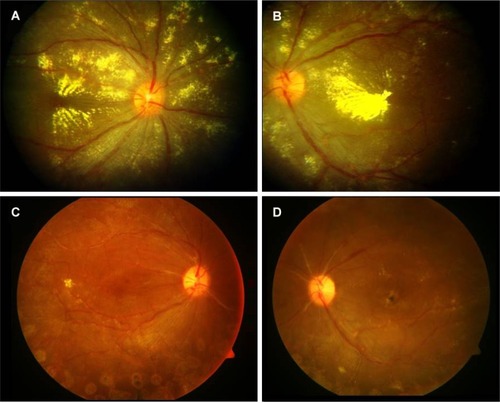

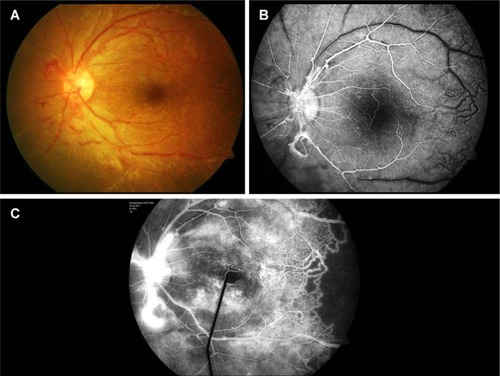

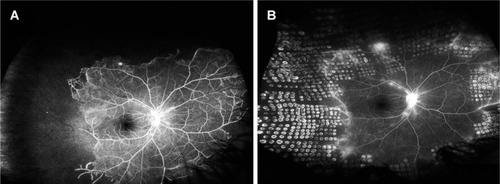

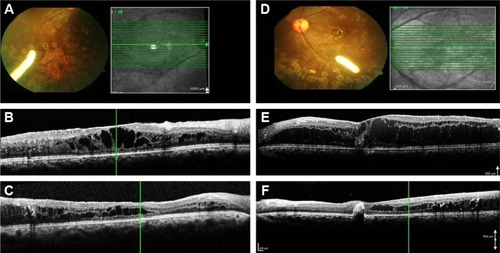

Samuel et alCitation3 classified the clinical features of IRVAN into major and minor criteria, and diagnosis is based on a constellation of these clinical features. The three major criteria are retinal vasculitis, aneurysmal dilations at arterial bifurcations, and neuroretinitis, while minor criteria are peripheral capillary nonperfusion, retinal neovascularization, and macular exudation (–). Aneurysmal dilatations typically have a dynamic nature in terms of their shape, size, and location, which is characteristic of IRVAN. Samuel et al also devised a staging classification of disease progression and the effect of treatment on the basis of this classification system. The staging was proposed to quantify the degree of retinal ischemia. Stage 1 is the presence of macroaneurysms, exudation, neuroretinitis, retinal vasculitis (), stage 2 is when there is angiographic evidence of capillary nonperfusion ( and ), stage 3 is when there is posterior-segment neovascularization of the disk or elsewhere and/or vitreous hemorrhage ( and ), stage 4 is the presence of anterior-segment neovascularization, and stage 5 is neovascular glaucoma.Citation3

Figure 1 Left eye of 12-year-old male.

Figure 2 Fundus photography of eyes of 12-year-old male.

Figure 3 Left eye of an 11-year-old girl who presented with mild blurring of vision.

Figure 4 Fundus photography of both eyes of an 11-year-old girl who presented with blurring of vision both eyes.

Figure 5 Left eye of an 11-year-old IRVAN patient.

Abbreviation: IRVAN, idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis.

Figure 6 Wide-field fluorescein angiography in a case of IRVAN; an 11-year-old girl who presented with blurring of vision both eyes.

Abbreviation: IRVAN, idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis.

The disease has a slight female preponderance, with an average age at presentation of 30–40 years.Citation1–Citation3 It is usually an asymptomatic disease, but if left untreated may lead to severe visual loss. It is usually bilateral, but a few cases of unilateral involvement have also been reported and a few cases where it was unilateral to start with and eventually went on to involve both eyes.Citation22,Citation23

Kincaid and SchatzCitation1 first described the features of a disease entity with involvement of the bilateral retinal arteries with multiple aneurysmal dilatations, which was later given the nomenclature of IRVAN by Chang et al,Citation2 in which they further described similar features in a total of ten patients. Vision is usually not affected during initial presentation, and there is deterioration in vision secondary to exudation or due to peripheral ischemia, leading to neovascularization. There is a presence of retinal vascular inflammation, which leads to anterior chamber and vitreous cells. The most characteristic feature is the presence of numerous aneurysmal dilatations of retinal and optic nerve-head arterioles. The aneurysms measure 75–300 µm in diameter and are present on the optic nerve head and on retinal arterioles at or near the major branching sites. They typically have a triangular or Y-shaped morphology but can also be seen in a coiled configuration, which has been described to appear as knots tied into an arterial tree (). These macroaneurysms have a tendency to leak with lipid deposition, which can lead to visual loss if there is involvement of the macula. Various studies have documented changes in the size, shape, and location of the aneurysms over time. Some have linked it to the effect of laser treatment applied to the peripheral ischemic areas, while some have noticed spontaneous resolution unrelated to any kind of treatment, thus suggesting that it could be the natural course of the disease.Citation7,Citation18,Citation24–Citation26 Yeshurun et alCitation18 noticed that new lesions appeared usually in proximity to sites of resolved lesions. They also noticed that fusiform lesions enlarged and acquired a more saccular appearance, while other lesions transformed in a reversed pattern from larger saccular aneurysms to smaller fusiform ones. These morphological changes were associated with worsening in the exudative state in the eyes. The migratory inflammatory processes involving the alternate segments along the vascular tree could explain this kind of migratory nature of aneurysms, whereby the affected segment may weaken and under the influence of intravascular hydrostatic pressure dilates and acquires a fusiform shape. Further weakening could lead the ectasias to attain a saccular appearance. With resolution of the inflammation within the involved vessel-wall area, vascular strength may be regained, which consequently leads to restoration of normal contour.

Neuroretinitis and retinal vasculitis are seen in all patients. Most often, retinal phlebitis predominates; however, in cases of IRVAN, there is mostly arterial involvement. (, , and ). The other regrettable but consistent features of IRVAN include exudative retinal detachment and peripheral capillary nonperfusion areas ( and ). Chronic upregulation of VEGF from peripheral ischemia contributes to increased vasopermeability of diseased retinal vessels, persistent macular edema, and subsequent diffuse lipid deposition.Citation27,Citation28 Exudative retinopathy is usually seen adjacent to retinal and/or optic nerve-head aneurysms and in the peripapillary area. It is believed that patients with IRVAN suffer in part from retinal microvascular disease processes similar to other disease processes, which eventually leads to neovascularization as in diabetic retinopathy, but some time is required before sufficient nonperfusion develops and leads to onset of retinal neovascularization. Therefore, careful follow-up is warranted. Neovascularization of the retina and anterior segment can occur, which can have a devastating effect on visual acuity.Citation2,Citation3 Though capillary nonperfusion is universally present in all adult cases of IRVAN, there might be absence of this feature in pediatric cases, as shown by reports of pediatric IRVAN cases.Citation29,Citation30 In their study, three of seven patients less than 18 years of age did not show any evidence of peripheral capillary nonperfusion.Citation1,Citation3 They also showed that presentation of IRVAN may be delayed in these cases, as evidenced by the resolution of exudates and no associated edema.Citation29,Citation30

Secondary vascular occlusions after krypton-laser photocoagulation of aneurysmal dilatations have been reported, but primary appearance of vascular occlusion is a very rare phenomenon and has been reported in only two cases.Citation31 Parchand et alCitation32 reported a patient who on detailed workup for inflammatory and infectious vascular diseases was found to have elevated levels of homocysteine. Similarly, Venkatesh et alCitation33 found a patient to have combined arteriolar and venular obstruction unrelated to laser photocoagulation. They speculated that patients with IRVAN may already be predisposed to vascular occlusion. Similarly, Hammond et alCitation34 showed an association with increased intracranial pressure, as evidenced by raised opening pressures on lumbar puncture. They suggested that IRVAN with prominent disk edema could be associated with raised intracranial pressure.

Imaging in IRVAN

Imaging plays a major role in the diagnosis of IRVAN, monitoring of intraocular inflammation, and response to treatment, as well as the development of complications.

FFA findings

FFA is a very useful tool in the diagnosis and management of patients with IRVAN.Citation35–Citation38 FFA depicts not only fine, ophthalmoscopically invisible, morphologic vascular changes but also changes in retinal circulatory dynamics. The intensity of dye leakage through the walls of diseased vessels is directly proportional to inflammatory process activity.Citation4 Such changes as dilatation, macroaneurysm formation, rete mirabile, and neovascularization characterize early stages, while occlusion and sheathing of veins denote advanced stages of vasculitis.

Aneurysmal dilatations

FFA accentuates numerous aneurysmal dilatations on the optic nerve head and retinal arterioles, and shows extensive leakage from these dilatations with late staining of aneurysmal dilatations (, and ). The optic nerve heads demonstrate leakage and staining in the later phase ().

Vascular leakage

Due to inflammation and breakdown of the blood–retina barrier, FA can demonstrate diffuse, segmental, or focal vascular leakage. The leakage is mainly limited to the arterioles. Often, vascular leakage is mainly concentrated on areas of aneurysmal dilatation ( and ). Conventional fundus cameras can capture only the central 30° or 50° field of view. Ultrawide-field imaging of the fundus allows the clinician to obtain more information compared to regular field scansCitation38 ().

Capillary nonperfusion

Retinal ischemia is a feature of patients with IRVAN. This presents on FA as areas of capillary dropout ( and ). The areas of nonperfusion are mainly in the periphery or macula. Macular ischemia results in poorer visual outcome, despite successful control of inflammation.

Retinal neovascularization

Retinal ischemia and inflammation can result in release of VEGF, which stimulates new-vessel proliferation ( and ). New vessels can be found at the optic disk or elsewhere on the retina. Patients with areas of capillary nonperfusion in more than two quadrants require laser photocoagulation, and therein lies the importance of FFA, mainly ultrawide-field FFA,Citation38 in picking up these lesions.

Macular edema

Patients with active retinal vasculitis may have reduced visual acuity, due to the presence of macular edema. Retinal thickening can be observed on FA as leakage of dye in the macula or presence of diffuse hyperfluorescence increasing toward the late phase (). There may be an increase in macular leakage following laser photocoagulation performed for retinal ischemia.

Neuroretinitis

FFA shows optic nerve-head hyperfluorescence that may be associated with staining of the optic nerve head in late frames (). This needs to be differentiated from neovascularization of the optic nerve head. FFA helps in planning of grid-laser treatment as combination therapy with anti-VEGF in cases of massive exudation causing low vision. FFA also serves as a tool to follow these patients up to check for any active neovascularization, adequacy of laser treatments, and any skipped areas of laser treatment. In addition, wide-field techniques also assist the clinician to assess peripheral vascular lesions and aid in guiding further therapyCitation38 ().

Indocyanine angiography findings

Indocyanine green (ICG) angiography is a useful tool for looking for changes occurring at the level of choroid that cannot be picked up by FFA. We can see dilated and leaky large choroidal vessels in early- to intermediate-phase ICG angiography, which may indicate a vasculitic component with vessel damage. There may be peripheral patchy areas of ICG hypocyanescence on the intermediate–late phase of angiography, which may be caused by an impairment of physiological ICG diffusion from the fenestrated choriocapillaris because of vascular obstruction. These areas may at times represent whole-thickness, space-occupying inflammatory choroidal lesions or choroidal stromal atrophy with an intact, undamaged retinal pigment epithelium, both preventing staining of the choroidal stroma on ICG angiography. In addition, ICG angiography is also useful in the detection of retinal aneurysmal dilatations or tied-knot-like sacculations that have been shown to remain well delineated throughout the examination as focal areas of retinal hypercyanescence without leakage.Citation22,Citation29,Citation35

OCT findings

OCT is a valuable tool for assessing pathological changes occurring at the macula in cases of IRVAN.Citation39 It is helpful in detecting early subclinical findings, such as vitreomacular traction and epiretinal membrane, which are the causes of low vision in these cases. It also shows diffuse macular thickening with back-scattering shadowing of the inner retinal layers, suggestive of areas of macular exudation, and helps in assessing response to treatment in patients who receive anti-VEGF or Ozurdex injection and/or with laser treatment (). OCT is useful in planning surgical interventions and assessing surgical outcome in patients undergoing surgery for vitreomacular traction or epiretinal membranes secondary to the disease process. As such, OCT provides us with further insight regarding contributing factors in vision loss in IRVAN patients.

Figure 7 Right and left eye of a case of IRVAN; a 12 years-old-girl who presented with blurring of vision both the eyes.

Abbreviation: IRVAN, idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis.

Systemic association

IRVAN is a rare clinical entity that is generally not associated with any systemic anomalies. However, since there is a component of inflammatory process involved in the disease process, certain systemic associations have been shown in various reports. The natural history and pathogenesis of IRVAN is not clear yet, and the basic underlying mechanism is postulated to be triggered by an inflammatory process. Among patients with IRVAN, inflammation may be activated by hypersensitive reactions to tubercular antigensCitation40,Citation41 or fungal elements, as has been reported.Citation25 A number of studies have shown a strong association between vasculitis and tubercular etiology. Therefore, it can be postulated that IRVAN occurs as an extended spectrum of ocular tuberculosis, especially in tuberculosis-endemic areas.Citation6,Citation40,Citation41

Systemic workup has revealed a positive serum test for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCAs) in certain cases, with features typical of IRVAN on FFA.Citation11,Citation12 Neutrophil-mediated injury of the endothelial cells is considered an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of ANCA-related vasculitis. However, there are no systemic features of polyarteritis nodosa or Wegener’s granulomatosis, suggesting that there could be an isolated ocular form of p-ANCA-associated vasculitis. There has been a report in which an association of IRVAN with antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome was shown and a possible association postulated, since both diseases affect the vasculature.Citation42 Therefore, when evaluating a patient with IRVAN, one could consider the possibility of lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibodies, especially if the patient also has a history of nonocular vascular thrombosis. Several features have been reported about IRVAN, including various associations, but it remains a poorly understood disease spectrum.

Differential diagnosis

Though similar to senile acquired macroaneurysms, vascular dilatations are readily discernible. Senile acquired macroaneurysms are unilateral, often round, frequently associated with systemic hypertension, and are usually seen in individuals in their sixth to seventh decades.Citation43 These macroaneurysms are usually single or few in number and regular, round, or ovoid, and there is absence of inflammation. Histologically, in cases of acquired macroaneurysms, they show linear breaks in the arterial walls, surrounded by fibrin clots, blood, lipids, and fibroglial response, which have a tendency to bleed.Citation43–Citation46 Cases of IRVAN do not show features of preretinal, intraretinal, or vitreous hemorrhage secondary to macroaneurysms. Also, aneurysmal dilatations in cases of IRVAN are frequently observed along the optic nerve head, giving an appearance of elongation, as they are situated in the arteries traversing the optic nerve head.Citation1–Citation3,Citation18

The presence of retinal vasculitis and peripheral non-perfusion in IRVAN makes Eale’s disease a potential differential. However, Eale’s disease typically affects younger male patients, and is associated with a positive tuberculin test, vestibuloauditory deficits, and (rarely) cerebral infarction. In Eale’s disease, there is more predilection of the retinal veins not associated with aneurysms or optic nerve-head vascular tortuosity.Citation47 Segmental retinal periarteritis is an aspecific response of the retinal vessels seen in chorioretinitis. Unlike in cases of IRVAN, these cases have discrete plaques on the surface of the retinal arteries.Citation48 Retinal arteritis associated with Behçet’s disease is an occlusive panarteritis and associated with systemic features of oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, and hypopyon.Citation49

Multiple arterial ectasias with uveitis can be seen in cases of sarcoidosis, especially in patients above 60 years of age and with a history of hypertension.Citation14 They present with bilateral multiple arterial ectasias, such as beading, macroaneurysms, comma-like ectasias, kinking with vasculitis, staining of the optic disk, and multiple peripheral round “punched-out” hypopigmented chorioretinal scars. These usually cause periphlebitis and cystoid macular edema. Periphlebitis may induce venous occlusions and retinal neovascularization.Citation14,Citation50 This can be differentiated from IRVAN by the age of patients, features of systemic sarcoidosis, and presence of hypopigmented chorioretinal scars.

Polyarteritis remains a consideration in which there is necrotizing arteritis, and it occurs in all ages and affects both the sexes.Citation51,Citation52 The disease is thought to represent hypersensitivity of the arterial wall to various antigens. It primarily affects medium–small arteries and occasionally adjacent veins. The inflammatory weakening may lead to “punching out”, as seen in IRVAN. Polyarteritis nodosa is a systemic disease where there is history of hypertension and proteinuria with positive p-ANCAs.

Aneurysmal dilatations appear similar to the telangiectasias and macroaneurysms. Retinal telangiectasias are seen in Coat’s disease and Leber’s miliary aneurysms.Citation15,Citation16 These conditions produce vascular dilatations and exudation unilaterally, and saccular dilatations are seen along both arteries and veins. Dilatations occur both centrally and peripherally, and in Coat’s disease anterior-segment inflammation is not seen.

Arterial embolism may also be associated with aneurysms, and they are associated with mitral valve prolapse, which can be ruled out by a thorough cardiac evaluation and electrocardiography.Citation17 Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus can present with arterial occlusions, but these are associated with cotton-wool spots, larger retinal infarcts, and optic disk infarctions.Citation53 Similarly, in cases of Takayasu’s disease, occlusive changes are seen in major arteries due to giant-cell infiltration, resulting in arterial aneurysms like outpouchings.Citation54

Treatment

There is little information in the literature about the natural history and visual outcome of this disease. All reports have had some kind of limitations, such as small samples, short follow-up, or adopting therapeutic regimens that had limited validity. Over the years, many therapeutic regimens have been adopted, such as medical, surgical, and photocoagulation.

The presence of anterior-segment and posterior-segment inflammation along with the migratory nature of aneurysms suggests that there is an inflammatory process involved in the disease process. However, therapeutic response to steroids is absent or minimal.Citation3 In the quest for better alternatives, anti-TNF and anti-VEGF therapies have been tried, with promising results.Citation21,Citation55,Citation56

Samuel et alCitation3 published the most relevant case series of IRVAN syndrome comprising 44 eyes of 22 patients. They divided this clinical entity into five stages to determine whether early intervention with PRP affected the visual outcome and natural history of the disease. They showed that the visual prognosis was dependent mainly on early initiation of treatment for ischemic retinal disease. All eyes treated with laser in stage 2 maintained 20/20 vision without disease progression. Many treated eyes in stage 3 also maintained 20/40 visual acuity or better; however, 25% of patients in stage 3 ended with 20/200 visual acuity or worse, due to disease progression. Half of the patients treated in stages 4 and 5 progressed to severe vision loss despite treatment. This showed the importance of early diagnosis and treatment, with stage 2 cases having the best visual results. The rationale for laser treatment is based on the results of the CRVO study, which recommends argon-laser PRP in high-risk proliferative retinopathy and irises with neovascularization.Citation57,Citation58 The presence of iris or retinal neovascularization is a prerequisite for initiating laser treatment. However, Samuel et alCitation3 showed that visual prognosis is dependent on early initiation of laser treatment, irrespective of the presence of neovascularization. Exudative maculopathy, which is also responsible for decreased vision, is treated with grid/focal photocoagulation, after which patients are seen to maintain good vision within one line of initial vision or improvement of up to two lines. However, direct photocoagulation of leaking macroaneurysms is contraindicated, as it leads to occlusion of blood vessels originating at the site of vessel burn.Citation32 The precise time to initiate treatment is not clearly known, as we do not wait for neovascularization in these cases. Rouvas et alCitation59 advocated deferral of PRP when peripheral ischemia is present in fewer than two quadrants of the retina. This did not appear to result in progression of ischemia at follow-up of 3 and 4 years for two of their six patients. Therefore, treatment should be withheld until ischemic area involvement is in more than two quadrants, which is better evidenced by wide-field FA.

Theoretically, the nature of pathology is similar to that found in retinal neovascularization due to diabetes. VEGF-and non-VEGF-mediated mechanisms appear to be involved in the pathogenesis of IRVAN, and thus there lies the importance of combination therapy.Citation60 Anti-VEGF therapies are emerging as a new approach in treating all retinal diseases where there are high levels of VEGF produced due to retinal ischemia.Citation61,Citation62 As there have been favorable results with anti-VEGF treatment in age-related macular degeneration and diabetes, its use has been attempted in cases of IRVAN based on similar principles. It is especially advocated in the presence of neovascularization, ie, stages 3–5, as a combined treatment along with PRP, as is done in high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy cases. Therefore, although PRP remains the gold standard for IRVAN treatment, intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF could be an option in advanced cases with neovascularization.Citation55,Citation56

Based on experimental models on the role of TNFα in mediating inflammation and retinal tissue destruction, Cheema et alCitation21 used infliximab to treat two of their patients with IRVAN, and noted a dramatic resolution of ocular inflammation and reduction in retinal exudation after the first dose. This resulted in a reduction of leakage from the optic nerve and resolution of macular edema, thus improving vision. However, it did not have any effect on peripheral non-perfusion areas, emphasizing the importance of combination therapy with laser treatment in these patients. However, this treatment modality should be used with caution, as there lies a risk of reactivation of opportunistic infections and activation of latent tuberculosis.

The role of steroids also remains unclear. Saatci et alCitation63 used bilateral dexamethasone implants with oral immunosuppressants in the form of azathioprine tablets and PRP for treating a case of IRVAN. Empeslidis et alCitation64 administered a unilateral dexamethasone implant to combat persistent macular edema despite previous PRP, oral steroid treatment, and pars plana vitrectomy in a patient with stage 3 IRVAN syndrome. There was significant improvement in visual acuity with the implant, and the authors noted a marked reduction in macular thickness as well (). Surgical management is reserved for end-stage disease where the patient develops vitreous hemorrhage secondary to neovascularization or there is tractional retinal detachment. Pars plana vitrectomy with epiretinal membrane peeling is advocated where there is significant epiretinal membrane and in cases of vitreomacular traction.

Complications associated with IRVAN

IRVAN is a rare retinal vascular disease, and if left unrecognized and untreated it can lead to bilateral visual loss. The natural history of IRVAN is uncertain and clinical features follow an erratic course, but the progression to vision-threatening complications follows a more predictable pattern. The staging system of IRVAN provides a framework from which the cadence of progression of retinopathy can be gauged and estimated, thus assisting in initiation of timely intervention to prevent its sequalae.Citation3 It appears to have a more aggressive course than other forms of ischemic retinopathies, whereby it can quickly develop large areas of capillary non-perfusion areas, leading to neovascularization with secondary vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachments, and neovascular glaucoma. Diminished retinal perfusion leading to retinal hypoxia may be one of the factors in the formation of new vessels on the iris and the anterior-chamber angle on the retina and optic nerve head. Several cell types in the retina synthesize VEGF, but under conditions of retinal ischemia, Müller cells play a major role in their production. VEGF is a potent angiogenic stimulator that promotes several steps of angiogenesis, including proliferation, migration, proteolytic activity, and capillary-tube formation, causing both normal and pathologic angiogenesis. VEGF also induces vascular hyperpermeability and endothelial proliferation, along with its migration.Citation27,Citation28 It is important to look for neovascularization along the pupillary margins where it appears first, which is the earliest evidence of anterior-segment rubeosis.Citation65 Gonioscopy and iris FA also help in picking up these complications where there is peripupillary leakage on FFA. The high rates of progressive neovascular complications despite laser photocoagulation of stage 3 patients and poor visual prognosis in stage 4 and 5 groups suggest that there is extreme difficulty in controlling the ischemic complications of the disease once neovascularization develops. Therefore, early laser treatment with adjunctive therapy in the form of anti-VEGF or TNF inhibitors like infliximab is advocated in such patients.

Conclusion

IRVAN is an isolated retinal vascular disease with a constellation of ocular features. Due to its unique spectrum of features, this disease entity is now being recognized more and more by retina specialists. It can progress rapidly to visual loss, due to ischemic sequelae or massive exudation. Early intervention in these patients in the form of prompt laser treatment without waiting for neovascularization to develop is important, as the nature of the disease is more aggressive than other ischemic retinopathies. Anti-VEGF and infliximab have been used as adjunctive treatment in IRVAN with laser treatment to reduce disease progression. However, the role of steroids remains uncertain. Systemic pathology is not usually identified, though some associations have been made with p-ANCAs, sarcoidosis, raised intracranial pressure, antiphospholipid antibodies, tuberculin hypersensitivity, and raised homocysteine. In spite of these associations, laboratory tests are advocated on a case-by-case basis, and blanket investigation is not recommended.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KincaidJSchatzHBilateral retinal arteritis with multiple aneurysmal dilatationsRetina198331711786635351

- ChangTSAylwardGWDavisJLIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuro-retinitisOphthalmology1995102108910979121757

- SamuelMAEquiRAChangTSIdiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN): new observations and a proposed staging systemOphthalmology20071141526152917678691

- KarelIPeleskaMDivisováGFluorescence angiography in retinal vasculitis in children’s uveitisOphthalmologica19731662512644709366

- GassJDStereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment3rd edSt LouisMosby1987

- JampolLMIsenbergSJGoldbergMFOcclusive retinal arteriolitis with neovascularizationAm J Ophthalmol197881583589

- OwensSLGregorZJVanishing retinal arterial aneurysms: a case reportBr J Ophthalmol1992766376381420048

- CoganDGOphthalmic Manifestations of Systemic Vascular DiseasePhiladelphiaWB Saunders1974

- SandersMRetinal arteritis, retinal vasculitis, and autoimmune retinal vasculitisEye (Lond)198714414653327709

- KnoxDLIschemic ocular inflammationAm J Ophthalmol19656099510025857026

- SoheilianMNouriniaRTavallaliAPeymanGAIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA)Retin Cases Brief Rep2010419820125390402

- NouriniaRMontahaiTAmoohashemiNHassanpourHSoheilianMIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodyJ Ophthalmic Vis Res2011633033322454754

- HoganMJAlvaradoJAWeddleJEHistology of the Human EyePhiladelphiaWB Saunders1971

- VerougstraeteCSnyersBLeysACaspers-VeluLEMultiple arterial ectasias in patients with sarcoidosis and uveitisAm J Ophthalmol200113122323111228299

- DuaneTDClinical OphthalmologyHagerstown (MD)Harper and Row1978

- ChisholmIAChawlaJCNanjianiMRRetinal macroaneurysmsCantSJVision and CirculationSt LouisMosby1976323329

- CltriderNDIrvineARKlineHJRosenblattARetinal emboli in patients with mitral valve prolapseAm J Ophthalmol1980905345397424751

- YeshurunIRecillas-GispertCNavarro-LopezPArellanes-GarciaLCervantes-CosteGExtensive dynamics in location, shape, and size of aneurysms in a patient with idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndromeAm J Ophthalmol2003135111812012504719

- MaitlandCGMillerNRNeuroretinitisArch Ophthalmol1984102114611506466175

- CaldwellRBMartoliMBehzadianMAVascular endothelial growth factor and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectivesDiabetes Metab Res Rev20031944245514648803

- CheemaRAAl-AskarECheemaHRInfliximab therapy for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysm, and neuroretinitis syndromeJ Ocul Pharmacol Ther20112740741021563921

- GedikSYilmazGAkçaSAkovaYAAn atypical case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndromeEye (Lond)20051946947115184951

- MoosaviMHosseiniSMShoeibiNAnsari-AstanehMRUnilateral idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) syndrome in a young femaleJ Curr Ophthalmol201527636627239579

- SashiharaHHayashiHOshimaKRegression of retinal arterial aneurysms in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN)Retina19991925025110380034

- El-AsrarAMJestaneiahSAl-SerhaniAMRegression of aneurysmal dilatations in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) associated with allergic fungal sinusitisEye (Lond)20041819720114762419

- TomitaMMatsubaraTYamadaHLong term follow up in a case of successfully treated idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN)Br J Ophthalmol20048830230314736797

- MichaelsonICThe mode of development of the vascular system of the retina with some observations of its significance in certain retinal diseasesTrans Ophthalmol Soc UK194868137180

- FolkmanJMerlerEAbernathyCIsolation of a tumor factor responsible for angiogenesisJ Exp Med19711332752884332371

- KrishnanRShahPThomasDSubacute idiopathic vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) in a child and review of paediatric cases of IRVAN revealing preserved capillary perfusion as a more common featureEye (Lond)20152914515125233821

- DiLoretoDAJrSaddaSRIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) with preserved perfusionRetina20032355455712972774

- RussellSRFolkJCBranch retinal artery occlusion after dye yellow photocoagulation of an arterial macroaneurysmAm J Ophthalmol19871041861873618718

- ParchandSBhalekarSGuptaASinghRPrimary branch retinal artery occlusion in idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndrome associated with hyperhomocystenemiaRetin Cases Brief Rep2012634935225389928

- VenkateshPVergheseMDavdeMGargSPrimary vascular occlusion in IRVAN syndromeOcul Immunol Inflamm20061419519616766406

- HammondMDWardTPKatzBSubramanianPSElevated intracranial pressure associated with idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis syndromeJ Neuroophthalmol20042422122415348989

- PichiFCiardellaAPImaging in the diagnosis and management of idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN)Int Ophthalmol Clin20125227528222954951

- McDonaldHRDiagnostics and therapeutic challenges: IRVAN syndromeRetina20032339239912824842

- StanfordMRVerityDHDiagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients with retinal vasculitis. International ophthalmology clinicsInt Ophthalmol Clin2000406983

- LederHACampbellJPSepahYJUltra-wide-field retinal imaging in the management of non-infectious retinal vasculitisJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect201333023514542

- VenkateshPVashishtNGargSOptical coherence tomographic features in idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitisJ Ophthalmic Res20141712 Available from: http://paper.uscip.us/jor/JOR.2014.1002.pdf

- SinghRSharmaKAgarwalAVanishing retinal arterial aneurysms with anti-tubercular treatment in a patient with idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitisJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect20166826922651

- AgarwalAIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinopathy (IRVAN)Gass’ Atlas of Macular Diseases5th edPhiladelphiaSaunders2012534538

- KurzDEWangRCKurzPAIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis in a patient with antiphospholipid syndromeArch Ophthalmol201213025725822332229

- LewisRANortonEWGassJDAcquired arterial macroaneurysms of the retinaBr J Ophthalmol19766021301268157

- AsdourianGKGoldbergMFJampolLRabbMRetinal macroaneurysmsArch Ophthalmol197795624628557969

- PalestineAGRobertsonDMGoldsteinBGMacroaneurysms of the retinal arteriesAm J Ophthalmol1982931641717199821

- Abdel-KhalekMNRichardsonJRetinal macroaneurysm: natural history and guidelines for treatmentBr J Ophthalmol1986702113947596

- RenieWAMurphyRPAndersonKCThe evaluation of patients with Eales’ diseaseRetina19832432486675099

- OrlazesiNRicciardiLSegmental retinal periarteritisAm J Ophthalmol19594754454813637172

- ColvardDMRobertsonDMO’DuffyJDThe ocular manifestations of Behçet’s diseaseArch Ophthalmol19779518131817911254

- SpaltonDJFundus changes in sarcoidosisTrans Ophthalmol Soc UK19799916716995061

- ArmstrongSDConnDLDiagnosis and management of polyarteritis nodosaCompr Ther1981737446111415

- SheehanBHarrimanDGBradshawJPPolyarteritis nodosa with ophthalmic and neurological complicationsArch Ophthalmol195860537547

- CoppetoJLessellSRetinopathy in systemic lupus erythematosusArch Ophthalmol197795794797871263

- CoganDGOphthalmic Manifestations of Systemic Vascular DiseasesPhiladelphiaSaunders1974

- AkesbiJBrousseaudFXAdamRRodallecTNordmannJPIntravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in idiopathic retinitis, vasculitis, aneurysms and neuroretinitisActa Ophthalmol2010884041

- KaragiannisDSoumplisVGeorgalasIKandarakisARanibizumab for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis: favorable resultsEur J Ophthalmol201020479279420099231

- No authors listedPhotocoagulation treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: clinical application of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) findings, DRS report number 8Ophthalmology1981885836007196564

- No authors listedA randomized clinical trial of early panretinal photocoagulation for ischemic central retinal vein occlusion: the Central Vein Occlusion Study Group N reportOphthalmology1995102143414449097789

- RouvasANikitaEMarkomichelakisNTheodossiadisPPharmakakisNIdiopathic retinal vasculitis, arteriolar macroaneurysms and neuroretinitis: clinical course and treatmentJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect201332123514018

- MacIverSBassSJShermanJVisual acuity recovery in a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis aneurysms and neuroretinitisOptom Vis Sci201289E356E36322266813

- KumarASinhaSRapid regression of disc and retinal neovascularization in a case of Eales disease after intravitreal bevacizumabCan J Ophthalmol20074233533617392871

- DiagoTVallsBPulidoJSCoats’ disease associated with muscular dystrophy treated with ranibizumabEye (Lond)2010241295129620075964

- SaatciAOAyhanZTakeşOYamanABajinFMSingle bilateral dexamethasone implant in addition to panretinal photocoagulation and oral azathioprine treatment in IRVAN syndromeCase Rep Ophthalmol20156566225802506

- EmpeslidisTBanerjeeSVardarinosAKonstasAGDexamethasone intravitreal implant for idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitisEur J Ophthalmol20132375776023661543

- HenkindPOcular neovascularizationAm J Ophthalmol197885287301580695