Abstract

Recurrence of microbial keratitis in the presence of protozoal infection is very rare and infrequently reported unless predisposing factors are present. The association of recurrent microbial keratitis and synthetic microfibrils has never previously been reported to our knowledge. This single interventional case study describes the clinical course and treatment of a contact lens wearer who was treated for Acanthamoeba keratitis with superinfection from bacterial organisms in the presence of synthetic microfibrils. The presence of synthetic fibrils on a corneal ulcer base may act as a nidus for pathological organisms and interfere with normal corneal healing. This may result in infection recurrence and the growth of resistant opportunistic organisms.

Case report

A 72-year-old man presented with a two-week history of a red painful right eye. He was a soft contact lens wearer and wore his lenses for one month at a time, taking them out at the end of each day and disposing of the lenses at the end of the month. He had no past ocular, medical, or drug history of note. On examination his right visual acuity was 6/60. He had an inflamed eye with a central corneal epithelial defect 3.0 mm × 3.5 mm in size, with surrounding superficial and midstromal infiltration. The left eye was normal, with aided vision of 6/6. A corneal scrape of the right eye was performed for Gram staining and cultures were obtained on blood, chocolate, and Sabouraud’s agar, as well as non-nutrient agar overlaid with Escherichia coli. The Gram stain showed white blood cells only, and no organisms.

He was started on empirical antimicrobial treatment with topical ofloxacin hourly by day and night. Acanthamoeba was isolated from the non-nutrient plate after 72 hours. There was no growth of any other organisms, and the topical ofloxacin was discontinued. His treatment was switched to topical, ie, hourly polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02%, hourly propamidine isethionate 0.1% (Brolene®), prednisolone 0.5% four times daily, and atropine 1% three times daily. Over the following three months, his treatment was slowly tapered to topical, ie, polyhexamethylene biguanide four times daily, Brolene four times daily, and prednisolone 0.1% twice daily as his clinical picture improved.

At three months after initial diagnosis he complained of the right eye being red and sore again for several days. On examination he had an infiltrate in the center of a previously healing epithelial defect. A corneal scrape was sent for Gram staining and cultures were obtained. The Gram stain showed Gram-positive cocci in chains and he was empirically commenced on topical penicillin hourly, which was added to his prophylactic treatment for Acanthamoeba. After 48 hours, the blood agar grew Streptococcus viridans which was shown to be sensitive to penicillin. There was no growth on other culture media. Topical penicillin was tapered down to twice daily as his condition improved over the following month.

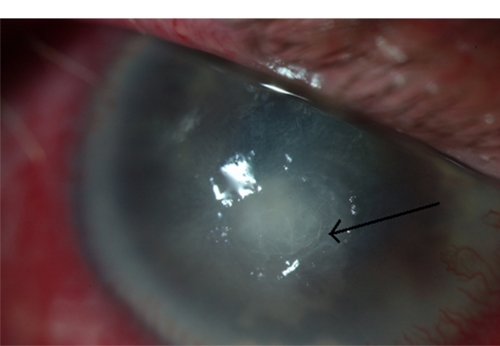

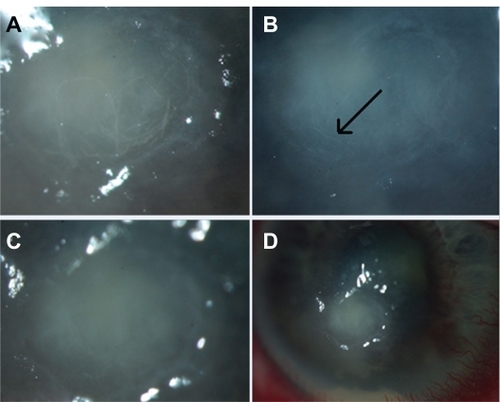

Four months after initial diagnosis, he again complained of a red painful right eye for one week. On examination he had an inferior corneal abscess and an intense anterior chamber reaction. Fine debris and hairs were noted in the base of the abscess and were removed by scraping (). Culture revealed growth of Pseudomonas species. The penicillin drops were stopped and he was treated with topical ofloxacin initially hourly and then tapered off over one month. Five months after initial diagnosis he complained of a one-day history of a painful right eye. Fine strands were noted on the surface of a central corneal abscess and were removed during the corneal scrape. These fibrils were present at follow-up despite removal (). Microbiology revealed growth of Stenotrophomonas species. He was treated with topical ofloxacin and gentamicin, to which the organism was found to be sensitive. The organism was resistant to ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, penicillin, cefuroxime, and fusidic acid. As he improved, fine fibrils were again seen in the healing cornea and were removed and sent for microscopy. This confirmed that the fibrils were synthetic and were not observed in previous/present cultures, and presumed to be derived from tissues which the patient was constantly using to wipe his eye. The patient was advised not to use tissues to wipe his eyes. The cornea continued to heal and topical treatment for Acanthamoeba (including steroids and ofloxacin) were continued and tailed off over a further three months.

Figure 1 Photograph showing active ulceration and presence of fibrils on ulcer base (indicated by arrow head).

Figure 2 (A) Magnified view of fibrils at the ulcer base at four months. (B) which were absent after immediate removal. (C) shows presence of fibrils (indicated by arrow head) the following week. (D) shows resolution of hyopyon with infiltration and injection of the globe in absence of fibrils.

In all episodes of infection, antibiotic sensitivities were determined using disc diffusion susceptibility testing. In all episodes of reinfection, scraping for Acanthamoeba was performed to exclude reactivation of the initial infection. One year following presentation, the right vision had improved to 6/18. The eye was quiet, with a residual corneal scar (). There have not been any further corneal problems.

Discussion

This patient had Acanthamoeba keratitis secondary to contact lens wear and then developed three episodes of bacterial keratitis. Microbial keratitis results from the interaction of a broad spectrum of pathogens and a diverse range of host responses. Recurrence is rare in the absence of predisposing factors, such as contact lens wear, ocular surface and corneal disease, corneal anesthesia, exposure, trauma, or previous corneal surgery.Citation1 When suspected, corneal scraping is mandatory in order to provide material for a microbiological diagnosis, debride necrotic tissue, and enhance antibiotic penetration. Corneal biopsy may be necessary in some cases of recurrence. The initial bacterial infection in this patient presumably was facilitated by the underlying Acanthamoeba keratitis and the use of corticosteroids.Citation2,Citation3 The presence of synthetic fibrils on the ulcer base presumably contributed to the infection recurrences by acting as a nidus for organisms and by interfering with corneal healing. It is noteworthy that the cornea finally healed with no further infections once the patient was instructed not to wipe his eye with a paper tissue.

Unfortunately it was not possible to obtain cultures directly from the tissue fibrils to confirm their direct association with the infective organisms. The first two bacterial infections were due to virulent organisms, such as pseudomonas and streptococcus. The culture of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia from the third corneal abscess was feasible because this is an opportunistic organism and infections typically occur in patients with compromised ocular surface and trauma.Citation4,Citation5 It has been reported previously in patients following penetrating keratoplasty.Citation3,Citation6,Citation7 This is the first case report of Acanthamoeba keratitis occurring in a contact lens wearer with preceding protozoal and bacterial keratitis. The characteristically resistant antibiogram of S. maltophilia may limit the therapeutic options. Fortunately in this patient treatment was adequately achieved with ofloxacin and fortified gentamicin.Citation8

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BennettHGHayJKirknessCMAntimicrobial management of presumed microbial keratitis: guidelines for treatment of central and peripheral ulcersBr J Ophthalmol19988221371459613378

- DavisRMSchroederRPRowseyJJAcanthamoeba keratitis and infectious crystalline keratopathyArch Ophthalmol198710511152415273314824

- LofflerKUWitschelHWhitish crystalloid corneal deposits. Infectious crystalline keratopathy in amoebic keratitisOphthalmologe1998958576577 German.9782736

- Ramos-EstebanJCJengBHPosttraumatic Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infectious scleritisCornea200827223223518216585

- SchaumannRSteinKEckhardtCInfections caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia – a prospective studyInfection200129420520811545481

- FernandesMGangopadhyayNSharmaSStenotrophomonas maltophilia keratitis after penetrating keratoplastyEye200519892192315761487

- ChenYFChungPCHsiaoCHStenotrophomonas maltophilia keratitis and scleritisChang Gung Med J200528314215015945320

- PenlandRLWilhelmusKRStenotrophomonas maltophilia ocular infectionsArch Ophthalmol199611444334368602781