Abstract

Purpose

Leber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis (LIN) is a rare condition that has been always considered an inflammatory disease, with emphasis given to the optic disc and neuroretina alterations.

Methods

A healthy 54-year-old woman presented a sudden loss of vision in the left eye, referring to periocular pain, headache, and mild fever for 1 month. Tests of best-corrected visual acuity, optical coherence tomography, infrared (IR) filter, fluorescein, and indocyanine green angiography were performed at the follow-up.

Results

The patient submitted to IR imaging, which revealed diffuse patchy choroidal infiltrates involving the posterior pole midperiphery, which were still present after 3 years of follow-up.

Conclusion

In this observation, we reported that choroidal involvement may occur in LIN. The IR filter is an important and noninvasive tool able to distinguish and follow choroidal infiltrates to better delineate the pathological process and elucidate the nature of the disease.

Keywords:

Introduction

Leber’s idiopathic neuroretinitis (LIN) is a rare pathologic condition. Presumably a cat scratch disease (CSD), neuroretinitis with negative serological test is self-limiting and characterized by monolateral visual loss, macular star, and optic disc edema.Citation1 The most common pathological manifestations associated with LIN are papillitis and neuroretinitis.Citation2

The disease may be preceded by viral-like symptoms 2 or 3 weeks before the beginning of visual problems.Citation1 Usually, this pathology affects young patients between the third and fifth decades without any particular prevalence for male or female.

The etiology is unknown, but parafebrile symptoms (eg, headache, mild fever, and weakness) might suggest an infectious cause for LIN.Citation1

The diagnosis is generally based on the clinical signs; every serological test should be negative for any infectious disease (with the exclusion of any metabolic distress such as diabetes and hypertension) or other general disease, such as sarcoidosis. The disease is usually self-limiting, with good prognosis for restoration of visual acuity.Citation1

Dreyer et al were the first to postulate Bartonella infection as a potential cause of LIN.Citation3 Historically, the study of this maculopathy has always focused attention on the retina. As suggested by the name, optic disc involvement gives emphasis to the peculiar lipid deposition around the macula that appears 1 or 2 weeks after the beginning of visual symptoms.

In this report, we describe a characteristic choroidal infiltration in a patient with LIN who has been followed with infrared (IR) fundus pictures.

Case report

A healthy 54-year-old woman was referred to our clinic with sudden loss of vision in her left eye, which was associated with periocular pain, headache, and mild fever for 1 month. Her general history was negative for hypertension and diabetes. Interestingly, she mentioned having cats in her house.

At the time of the examination, the patient’s visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye (RE) and 20/300 in the left eye (LE). Humphrey visual field analysis detected a centrocecal scotoma in the LE. Slit lamp examination showed no abnormalities in the anterior segment of either eye.

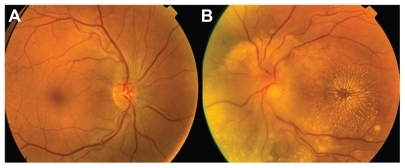

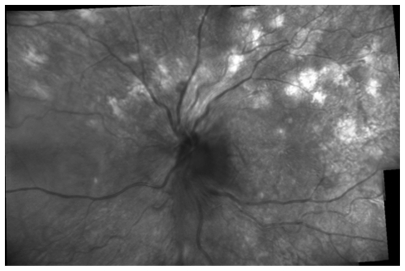

RE fundus examination was normal () and the LE revealed significant edema of the optic disc with retinal infiltrates at the posterior pole and a characteristic macular star from yellow exudates (). IR imaging (Heidelberg HRA, wavelength 830 nm) showed some optic disc edema surrounded by subretinal fluid, and diffuse, patchy, choroidal infiltrates involving the posterior pole midperiphery () otherwise invisible on ophthalmoscopy.

Figure 1 Color fundus photograph (A) right eye: normal appearance of the fundus; (B) left eye: showing edema of optic disc with some retinal infiltrates and exudates encircling the fovea in a shape similar to a star.

Figure 2 Infrared montage of the left eye showing the optic disc surrounded by small exudates and choroidal lesions in the posterior pole midperiphery.

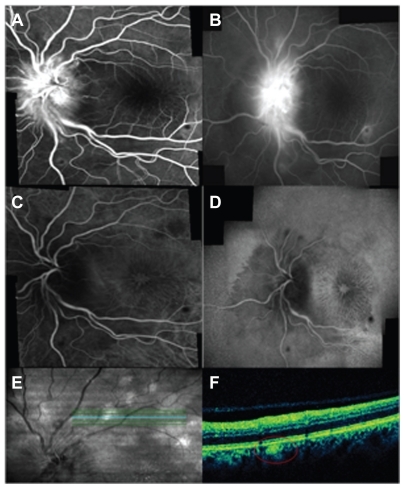

Fluorescein angiography (FA) conf irmed the optic disc swelling and some hypofluorescence from intraretinal infiltrates was detected (). Optic disc swelling and some masked hypofluorescence from the exudates as well as retinal infiltrates were recorded () on indocyanine green angiography (ICG). On early ICG, just some choroidal infiltrates were seen as an area of choriocapillaris hypoperfusion (). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) guided by IR imaging was able to confirm different focal loci of subretinal hyper-reflectivity corresponding to the choroidal infiltrates ().

Figure 3 (A and B) Left eye: early (20° magnification) and late-phase of fluorescein angiograms showing leakage of optic disc, stellate maculopathy, and the retinal lesions revealing early blockage and late staining; (C and D) early (20° magnification) and late-phase of indocyanine green angiograms confirming a macular star and revealing early and late blockage in the same lesions observed on FA; (E and F) red-free and optical coherence tomography scan showing a focal increased reflectance at the retinal pigmented epithelium–choriocapillaris complex corresponding to the lesions (red circle).

Laboratory investigations revealed negative Bartonella hensalae Ig-antibodies. Serological work-up was negative for other infectious agents, including Syphilis, Salmonella, Herpes simplex, and Toxoplasma. The results of chest X-ray, pelvis radiography, and brain magnetic resonance imaging were negative.

On the basis of the diagnosis of presumed chorioretinitis, the patient was treated with bolus of corticosteroids for 3 weeks. Two weeks after therapy, the patient was revaluated. Visual acuity was unchanged in the LE.

One year later, visual acuity in the patient’s LE improved to 20/40. Funduscopic examination of both eyes was normal, but LE’s IR imaging demonstrated unchanged choroidal infiltrates involving the posterior pole midperiphery, also observed by OCT (data not shown). The choroidal infiltrates observed by IR, also confirmed by OCT, were still found at the 2- and 3-year follow-up ().

Figure 4 (A) Infrared montage of left eye showing residual choroidal lesions in the posterior pole after 3 years of follow-ups (black line corresponds to the optical coherence tomography [OCT] cut and red circles highlight the choroidal infiltrates circled on OCT scan); (B) OCT scans revealing a focal increased reflectivity at the level of sub-retinal pigmented epithelium–choriocapillaris complex (red circle) confirming the presence of the lesions indicated on infrared montage (see Figure 4(A)).

![Figure 4 (A) Infrared montage of left eye showing residual choroidal lesions in the posterior pole after 3 years of follow-ups (black line corresponds to the optical coherence tomography [OCT] cut and red circles highlight the choroidal infiltrates circled on OCT scan); (B) OCT scans revealing a focal increased reflectivity at the level of sub-retinal pigmented epithelium–choriocapillaris complex (red circle) confirming the presence of the lesions indicated on infrared montage (see Figure 4(A)).](/cms/asset/2656ec0b-8eea-4323-b128-25fc1bf23029/doph_a_22833_f0004_c.jpg)

Conclusion

Leber’s maculopathy is a rare pathologic condition of the eye that in the literature has always been considered as a monolateral involvement of the optic disc and the retina that causes a discrete reduction of visual acuity and a centrocecal scotoma, usually with good recovery of vision over a period of about 6 months. Some authors consider LIN as a CSD associated with negative serological test results.Citation1 Gass and colleagues postulated that CSD may be a possible cause of LIN.Citation3

In addition, various studies have reported that other infectious and noninfectious causes may be responsible for LIN. Such infectious causes include Syphilis, Salmonella, H. simplex, Leptospirosis, Toxocara, and Toxoplasma. Noninfectious causes include marked hypertension, diabetes, increased intracranial pressure, and ischemic optic neuropathy. Citation4 In our report, the anamnesis and the complete serological work-up, as well as the battery of tests performed by the internist, were negative.

Therefore, we speculate that, based on the history (patient owned cats and showed viral-like symptoms 1 month before presentation), and general clinical and ophthalmology examination, this case may represent a CSD with negative serological test.

Several ocular manifestations of posterior segment damage may occur in patients with LIN, but the most common findings are papillitis and neuroretinitis;Citation2 however, unusual features in posterior segments of patients affected by CSD are also described in the literature.

In a paper by Khurana et alCitation5 a choroidal involvement detected by ultrasound was reported for a patient positive for CSD but was never clearly imaged. Choroidal thickening was described but never visualized, despite long-term follow up.Citation5

Mennel et alCitation6 reported multiple foci of chorioretinitis that developed as chorioretinal spots similar to scars secondary to multifocal choroiditis as clinical signs of the pathology. In a report by Ormerod et alCitation2 and Solley et al,Citation4 retinal or presumably choroidal white lesions in CSD documented only by fundus photography and FA did not explain the choroidal involvement. A recent study using OCT described only fluid accumulation in 2 separate subretinal spaces and in the outer nuclear-plexiform space.Citation7

In our patient, small, round, white retinal spots were noted in the posterior pole of LE, but these were considered as retinal infiltrates that we detected either on color fundus pictures and on FA and ICG angiography, which are common markers of retinal inflammation.

As a worldwide accepted theory, LIN seems to be an infectious disease with negative sierological test.Citation3

We think that our patient had a chorioretinal immunomediated inflammatory reaction and the choroidal involvement could be detected by means of IR imaging. If this assumption is true, choroidal infiltrates may represent areas of immunocomplex deposits which on ICG early frames block choriocapillaris fluorescence. This condition may have a certain similarity with the clinical picture described by Fardeau and colleagues,Citation8 who reported a choroidal involvement observed by ICG in a chorioretinal disease such as birdshot chorioretinopathy. These authors observed that hypofluorescent choroidal dots on ICG remained hypofluorescent during the chronicity of the disease, speculating that some choroidal lesion can be either chronic granulomas or stromal scars.Citation8

In our patient, IR imaging revealed several round, choroidal spots infiltrating the posterior pole midperiphery, not so evident with the above-mentioned exams, that were still evident at 1-, 2- and 3-year follow-up. OCT findings confirmed the persistence of the lesions throughout this period. These findings suggest that a chronic inflammatory condition of the choroid may be an important component in the pathogenesis of LIN, which remains to be further elucidated.

In conclusion, the choroidal involvement in LIN is to be considered as an important manifestation of the disease. IR imaging is an important and noninvasive tool able to distinguish and follow choroidal infiltrates. Because of these novel identifications, LIN has to be considered as a neurochorio-retinitis and should be evaluated as part of differential diagnosis considering other causes of choroiditis.

Disclosure

None of the authors has a conflict of interest with the submission. No financial support was received for this submission.

References

- ManicHBoissonnotMGicquelJJRoviraJCDighieroPLeber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis: about two casesJ Fr Ophtalmol2003261596312610411

- OrmerodLDSkolnickKAMenoskyMMPonDMRetinal and choroidal manifestations of cat-scratch diseaseOphthalmology19981056102410319627652

- DreyerRFHopenGGassJDSmithJLLeber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitisArch Ophthalmol19841028114011456466174

- SolleyWAMartinDFNewmanNJCat scratch disease: posterior segment manifestationsOphthalmology19991061546155310442903

- KhuranaRNAlbiniTGreenRLRaoNALimJIBartonella henselae infection presenting as a unilateral panuveitis simulating Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndromeAm J Ophthalmol200413861063106515629311

- MennelSMeyerCHSchroederFMMultifocal chorioretinitis, papillitis, and recurrent optic neuritis in cat-scratch diseaseJ Fr Ophtalmol20052810e1016395190

- KitameiHSuzukiYTakahashiMRetinal angiography and optical coherence tomography disclose focal optic disc vascular leakage and lipid-rich fluid accumulation within the retina in a patient with Leber idiopathic stellate neuroretinitisJ Neuro-Ophthalmol2009293203207

- FardeauCHerbortCPKullmannNQuentelGLeHoangPIndocyanine green angiography in birdshot chorioretinopathyOphthalmology1999106101928193410519587