Abstract

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is a benign disorder that is a common cause of acute ocular redness. The major risk factors include trauma and contact lens usage in younger patients, whereas among the elderly, systemic vascular diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and arteriosclerosis are more common. In patients in whom subconjunctival hemorrhage is recurrent or persistent, further evaluation, including workup for systemic hypertension, bleeding disorders, systemic and ocular malignancies, and drug side effects, is warranted.

What is a subconjunctival hemorrhage?

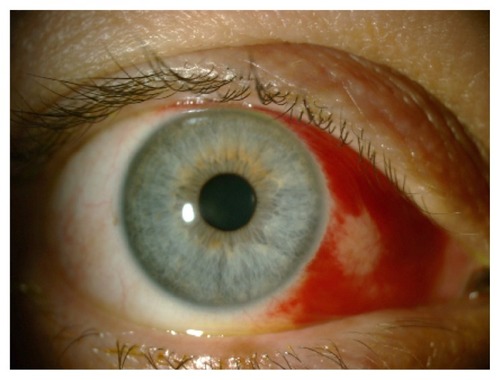

Subconjunctival hemorrhage (SCH) is a common benign condition of the eye that has characteristic features, such as the painless acute appearance of a sharply circumscribed redness of bleeding underneath the conjunctiva in the absence of discharge, and inflammation in contagious areas.Citation1 Reduction in visual acuity is not expected. It can vary from dot-blot hemorrhages to extensive areas of bleeding that render the underlying sclera invisible.Citation2 Histologically, SCH can be defined as hemorrhage between the conjunctiva and episclera, and the blood elements are found in the substantia propria of the conjunctiva when a subconjunctival vessel breaks.Citation3,Citation4 The incidence of SCH was reported as 2.9% in a study with 8726 patients, and increase with age was observed, particularly over 50 years of age.Citation5 It is thought that this significant increase depends on the increase of prevalence of systemic hypertension after the age of 50 years; also, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and the use of anticoagulation therapy becomes more frequent with aging.Citation4 Generally, SCH is most often seen in the inferior and temporal areas of the conjunctiva, but trauma causes localized hemorrhage at the site of injury, especially in the temporal areas.Citation4 The fibrous connections under the conjunctiva, including elastic and connective tissues, become more fragile with age, and this can be the reason for easy spread of hemorrhage in older patients.Citation4 Traumatic SCH is more likely to remain localized around the site of impact compared to diffuse SCH-associated systemic vascular disorders ().Citation4 SCHs are observed more often in summer, and this is related to the high frequency of local traumas in this season.Citation5,Citation6

What are the causes of subconjunctival hemorrhage?

The majority of cases are mostly considered to be idiopathic, since it is usually impossible and impractical to define the main cause of SCH. However, the clinician must have a systematic review scheme in mind, and major causes can be classified under ocular and systemic conditions, respectively.

The first study on the risk factors was reported by Fukuyama et alCitation5 in 1990, who showed that local trauma, systemic hypertension, acute conjunctivitis, and diabetes mellitus were the main causes or associated conditions of SCH. On the other hand, the cause of SCH was undetermined in about half of the patients. The relationship between age, local trauma, and systemic hypertension was assessed, and it was demonstrated that hypertension was seen more often in patients older than 50 years; however, local trauma was an important cause in all age-groups.Citation5,Citation6 Since the 1980s, the order of the risk factors of SCH has changed, and the number of patients with acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis has decreased, whereas contact lens usage and ocular surgery have become more common as underlying causes.Citation6 Mimura et alCitation6 showed that the major risk factors for SCH are trauma and contact lens usage in younger patients, and among older patients it is mostly associated with systemic vascular disorders, such as systemic hypertension, diabetes, and arteriosclerosis, which causes the walls of the blood vessels to become fragile.

Ocular causes include local trauma to the globe, injuries to the orbit, acute inflammation of the conjunctiva, conjunctival tumors, conjunctivochalasis, ocular amyloidosis, contact lens usage, ocular surgery, and ocular adnexal tumors.

Local trauma

Various types of local injuries to the globe constitute the common cause of SCH, spanning from a minor trauma originating from a foreign body or eye rubbing to major traumas, such as blunt or penetrating injuries of the globe, which can cause SCH at all levels.Citation2 Traumatic SCH tends to be more often in temporal areas than in the nasal areas.Citation4 At this point, it should always be kept in mind that the patient may not recall minor trauma until questioned in detail. Therefore, all patients presenting with SCH should be thoroughly asked about any possible trauma in the last few days.

Orbital injuries

SCH may develop 12–24 hours after the fracture of orbital bones and results from influent leakage of blood under the conjunctiva.Citation2,Citation7 Another similar phenomenon may be observed in cases of fractures of the base of the skull.Citation7 Hemorrhage under the conjunctiva can be located on the nasal side, coming from the fornix and in the absence of globe trauma; this appearance of the hemorrhage after 24 hours or more after a head injury is pathognomonic for basilar fractures.Citation7

Acute inflammation of the conjunctiva

Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, caused by enterovirus type 70, Coxsackie virus A24 variant, and less commonly adenovirus types 8, 11, and 19, is characterized by sudden onset of follicular conjunctivitis with mucoid discharge, epiphora, photophobia, eyelid edema, and conjunctival chemosis.Citation8,Citation9 It is often associated with multiple petechial hemorrhages of the upper palpebral and superior bulbar conjunctiva or widely extended SCH, especially localized to the temporal side.Citation10,Citation11

SCH was seen in 22.9% of 61 young immunocompetent males during the course of a measles epidemic in addition to conjunctivitis, which is a well-known diagnostic sign of measles.Citation12 A patient with chickenpox and normal platelet count was reported to develop unilateral SCH after the onset of typical cutaneous eruptions, without any other ocular complications.Citation13

Conjunctival tumors

Sometimes, SCH may result from vascular tumors of conjunctiva such as conjunctival lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma, cavernous hemangioma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma ().Citation14–Citation16 Cavernous hemangioma may be one of the factors that causes recurrent SCH, particularly in early adulthood.Citation16 Spontaneous rupture of conjunctival aneurysms that are associated with hereditary hemochromatosis patients can lead to recurrent SCHs.Citation17

Conjunctivochalasis

In recent years, there have been few reports evaluating the association between conjunctivochalasis and SCH.Citation18–Citation21 Mimura et alCitation18 reported that conjunctivochalasis-related parameters were more severe in SCH than in control patients, especially the grade of conjunctivochalasis, which was higher in the SCH patients at the nasal and temporal conjunctiva. According to these results, the authors suggested that conjunctivochalasis might contribute to the pathogenesis of SCH. In this report, they could not comment on the role of dry eyes in their patients but Liu et alCitation19 evaluated the tear film of spontaneous SCH patients by noninvasive interferometry. They demonstrated that Schirmer’s test I values of spontaneous SCH patients were lower than controls and that this could be related to elevation of conjunctiva and impairment of ocular surface wetting by SCH.Citation19 Another study reported by Wells et alCitation20 demonstrated that conjunctivochalasis resulting from circumferential drainage blebs following trabeculectomy might prompt SCH. The authors explained the possible mechanisms as damage of conjunctival vessels from the bulge of bullous conjunctiva, and degeneration of fibrous connections between the conjunctiva and Tenon’s capsule.Citation20,Citation21

Ocular amyloidosis

Conjunctival amyloidosis may be one of the unusual causes of spontaneous SCH. At this point, it is worth considering the simple classification of amyloidosis: (1) primary localized amyloidosis, (2) primary systemic amyloidosis, (3) secondary localized amyloidosis, and (4) secondary systemic amyloidosis.Citation22 In the eye, it usually presents as a painless, nodular mass or swelling of the eyelid and chemosis of the conjunctiva, and most commonly develops after inflammatory conditions.Citation23 A patient with primary localized conjunctival amyloidosis may present with recurrent SCH.Citation24,Citation25 Further evaluation for systemic disease is needed for these patients, although positive results are not often expected. Although the association of conjunctival amyloidosis with monoclonal gammopathies and multiple myeloma is not common, there is a case, reported by Higgins et al,Citation26 presenting with recurrent SCH and periorbital hemorrhage as the first sign of systemic amyloid light-chain amyloidosis. In patients with systemic disease such as multiple myeloma, which can be associated with amyloidosis, recurrent SCHs may occur even in the absence of prominent amyloid deposits. The possible pathogenesis of these hemorrhages can be explained as amyloid deposition within the walls of the vessels, leading to increase in the fragility of the vessels.Citation27

Contact lens usage

Contact lens-induced hemorrhages have been increasingly encountered in recent years as much as the other complications of contact lens wear. SCH in contact lens wearers can be related to contact lenses themselves or to other factors independent of contact lens usage ().Citation28 Tears resulting from improper lens insertion or removal are often the cause of the SCH, and frequently detailed examination of conjunctiva with slit-lamp biomicroscopy reveals a small tear near the limbus. Devices used for lens insertion or removal or long fingernails can promote this kind of injury in contact lens wearers.Citation28 The other important cause of SCH in these patients is a defect of the rim of the lens resulting from long wear of disposable lenses or material defects, especially in hard lenses, or surface deposits, which can be seen because of inadequate hygiene or improper storage conditions. The incidence of contact lens-related SCH was reported to be 5.0%.Citation6 A prospective study evaluating the clinical features of contact lens-induced SCH demonstrated that the hemorrhage was limited to temporal areas of the conjunctiva, whereas another study showed that the hemorrhage associated with systemic disorders tended to be seen haphazardly in more extensive areas.Citation28 This can be related to various factors, the most important being that contact lens usage and related injuries are more common in younger patients who usually do not have any systemic vascular disorders. Also, the connective tissue under the conjunctiva is still strong in young individuals, preventing the spread of hemorrhage.

Figure 3 Traumatic subconjunctival hemorrhage involving the nasal half of the bulbar conjunctiva caused by soft contact lens wear.

It should not be forgotten that although SCH in contact lens users can be related to the contact lenses most of the time, other ocular or systemic factors must also be considered. The contact lens should be inspected thoroughly, and recurrent hemorrhages should be accepted as a sign for further systemic evaluation. Patients with hematologic disorders should not wear contact lenses.Citation28,Citation29

Ocular surgery

Many ocular and nonocular surgical procedures may prompt SCH by different mechanisms. Cataract surgery, filtration surgery, refractive surgery, and local anesthesia techniques, such as sub-Tenon’s anesthetic injection and peribulbar block, might be the cause of recurrent SCH in the postoperative period.Citation30–Citation34

SCH may appear at each step of ocular surgery, especially starting with anesthesia. SCH during the conjunctival incision is one of the disadvantages of sub-Tenon’s anesthetic injection, and incidence of SCH during sub-Tenon’s anesthesia has been reported to be 7%–56%.Citation32,Citation33 Generally, it is limited to the area of conjunctival dissection. Although it does not have any effect on postoperative visual status of the eye, the patient may remain cosmetically unsatisfied.

There have been many reports suggesting that patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy did not show an increased rate of hemorrhagic complications during cataract surgery or local anesthesia, although some studies have reported that there was an increase in minor hemorrhagic complications in patients taking warfarin.Citation30,Citation35–Citation37 SCH was reported as the most frequent hemorrhagic complication in patients undergoing phacoemulsification and lens implantation who were treated with aspirin and warfarin.Citation30 It is widely accepted that anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents should be continued before cataract surgery. Patients on aspirin should continue taking the drug before cataract surgery and international normalized ratio (INR) should be checked in all patients on warfarin medication to maintain the therapeutic level.

LalchanCitation31 reported a case of patient on aspirin prophylaxis who had Fuchs’s heterochromic cyclitis (FCH) complicated by secondary open-angle glaucomatous optic neuropathy in his past ocular history and who presented with SCH as an intrableb hemorrhage. In that case, prolonged bleeding time was identified as the possible mechanism. Previously, Noda and HayasakaCitation38 reported two cases of FCH associated with recurrent spontaneous SCH two to four times per year, and the relationship between FCH and spontaneous recurrent SCH was unclear. Although the association of FCH with hyphema is well recognized, it was the first report demonstrating co-occurrence of FCH and spontaneous recurrent SCH.Citation31

A case of subconjunctival ecchymosis appearing after extraction of maxillary teeth has been reported.Citation39 The incidence of subconjunctival ecchymosis was found to be 19.1% after rhinoplasty in a study involving 73 patients.Citation40 SCH may occur during intraoperative positioning for lumbar spinal surgery as a rare complication, and also there have been reported cases of patients showing that SCH may occur during endoscopy, particularly in thrombocytopenic patients.Citation41,Citation42

Ocular adnexal tumors

Recurrent SCHs have been reported as the initial sign of anaplastic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland.Citation43 Ocular adnexal lymphoma can cause a set of signs and symptoms including ptosis, proptosis, and salmon-colored mass in the conjunctiva. Although not a common presenting sign, ocular adnexal lymphoma can be an underlying condition of recurrent SCH.Citation44

Systemic factors

Systemic factors that may lead to SCH can be classified as systemic vascular diseases, sudden severe venous congestion, hematological dyscrasias, systemic trauma, acute febrile systemic diseases, drugs, carotid cavernous fistulas (CCFs), menstruation, and delivery in newborns.

Systemic vascular diseases

The fragility of conjunctival vessels, as well as every other vessel elsewhere in the body, increases with age and as a result of arteriosclerosis, systemic hypertension, and diabetes.Citation2 Patients with vascular diseases may present with SCH repetitively, and the association of SCH and systemic hypertension has been investigated many times.Citation45 Severe SCH can result from uncontrolled hypertension, but it is also known that systemic hypertension may cause SCH even if it is controlled with drugs, because patients with hypertension tend to have microvascular changes in small vessels and in conjunctival vessels.Citation6,Citation45,Citation46 These findings make it necessary to check the blood pressure of each patient presenting with SCH. A study by Pitts et alCitation47 demonstrated that blood pressure checked at initial presentation and 1 week and 4 weeks after first presentation was higher in patients presenting with SCH than healthy controls; therefore, the incidence of hypertension was higher in patients with SCH. It is recommended that all patients with SCH have their systemic blood pressure checked.

Sudden severe venous congestion

SCH may occur after sudden severe venous congestion to the head, such as in a Valsalva maneuver, whooping cough, vomiting, sneezing, weight lifting, crush injuries, or spontaneously (without any apparent cause).Citation2 Compression of the thorax and abdomen as in accidents or explosions may act in the same way, and raised venous pressure can cause severe SCH.Citation2 Also, nonaccidental trauma should be seriously considered in infants presenting with bilateral isolated SCHs, particularly in the presence of facial petechia. This condition may be part of traumatic asphyxia syndrome caused by severe compression of the child’s thorax and abdomen or as a result of child abuse. The patient should be examined by a pediatrician from the perspective of high suspicion of abuse in the case of unexplained isolated bilateral SCHs.Citation48,Citation49

Asthmatic patients may face severe bilateral SCH at the peak of their fulminant attacks of severe asthma. A possible mechanism could be intrathoracic airway pressure rising to overcome airway obstruction, causing sudden congestion of blood into the superior vena cava.Citation50 Although uncommon, asthma may be an etiological factor in SCH, as well as pertussis infection causing coughing paroxysms.Citation51 Also with the same mechanism, there is a case report presenting with bilateral SCH resulting from voluntary breath-holding, an example of self-inflicted injury in psychiatric patients.Citation52

Hematological dyscrasias

Pathologies of the coagulation system, including the disorders associated with thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction, such as thrombocytopenic purpura, anemia, leukemia, splenic disorders, anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy, and uremia, may cause bleeding in conjunctival vessels.Citation2,Citation53,Citation54–Citation59

Parmeggiani et alCitation60 conducted a study to determine whether FXIII Val34Leu polymorphism, thought to be a predisposing risk factor for primary intracerebral hemorrhages in a previous study, might increase the risk of SCH, and showed that frequency of FXIII-mutated allele was higher in patients with SCH than in controls.Citation60,Citation61 These findings suggest that FXIII Val34Leu polymorphism can be considered a potential risk factor for spontaneous SCH, which needs to be validated by further studies.

An unusual bilateral massive spontaneous SCH can be an initial sign of acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a result of blood dyscrasia.Citation54 Another example for one of the same underlying serious conditions is idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, which can present with isolated unilateral SCH.Citation53 It must be borne in mind that any disorder that can cause hemostatic failure may be the reason for SCH.

Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapies, including aspirin, dipyridamole, clopidogrel, warfarin, and dabigatran (direct thrombin inhibitor), may prompt recurrent SCHs. It is important to take a detailed drug history to determine the usage of these drugs, as they may increase the risk of spontaneous or perioperative SCHs.Citation55–Citation58 Warfarin is the most commonly used anticoagulant in North America to treat venous and pulmonary thromboembolism and reduce the incidence of life-threatening thromboembolic events.Citation62 Bleeding is the most frequent adverse effect of warfarin use, and SCH is one of the minor bleedings that may be seen under warfarin medication.Citation63,Citation64 In an effort to identify patients with SCH on warfarin therapy, Leiker et alCitation58 reported that after evaluating 4334 patients, they noted 15 with SCH, – only 0.35% of patients. Only three patients were not in their targeted range of INR (INRs were greater than individual patient target range).Citation58 These findings were comparable with Superstein et al,Citation64 who found a rate of ocular bleeding of 4.8% (five of 126 patients on anticoagulation therapy), with two of those five patients with SCH.Citation64 It is important to determine the cause of SCH in this group of patients, as secondary causes previously mentioned, such as trauma, systemic hypertension, or blood dyscrasias, may prompt SCH besides anticoagulant therapy. Although supratherapeutic INRs have not been related to increased risk of SCH, patients on warfarin medication should have their INR checked.Citation58,Citation63

Systemic trauma

Splinter SCHs may be seen in the upper fornix, due to fat emboli originating from fractures of long bones in remote injuries.Citation2

Acute febrile systemic diseases

Petechial SCHs can be seen in febrile systemic infections, such as zoonosis (tsutsugamushi disease, scrub typhus, leptospirosis), enteric fever, malaria, meningococcal septicemia, subacute bacterial endocarditis, scarlet fever, diphtheria, influenza, smallpox, and measles.Citation2,Citation65–Citation68

Drugs

In addition to anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication, there are some drugs reported in the literature related to SCH. It should be kept in mind that interferon therapy in chronic viral hepatitis patients may give rise to SCH, and retinopathy and antiviral therapy, including polyethylene gycolated interferon plus ribavirin, can cause SCH in addition to vascular ophthalmological side effects.Citation69,Citation70

Carotid cavernous fistulas

SCH was one of the presenting signs of CCFs in two case reports. One of them was direct CCF presenting with sudden onset and pulsatile exophthalmos, SCH, ophthalmoplegia, and increased intraocular pressure.Citation71 The other CCF case was a patient with spontaneous unilateral SCH complaining of a right periorbital swelling.Citation72 Those two observations suggest that SCH may be a part of the clinical picture of CCF patients.

Miscellaneous conditions

Newborns may show SCH after normal vaginal delivery. In a study of 3573 healthy full-term newborns who had undergone an eye examination, the number of patients who showed SCH was reported as 50 (1.40%).Citation73

Spontaneous SCHs may be seen in menstruation, whereas hemorrhages from the conjunctiva occur more frequently in these cases.Citation2

An ophthalmologist, a general practitioner, or a physician may face patients with SCH many times in each step of daily clinical practice. The key point is to decide whether further investigation is necessary or not. In most cases, SCHs do not require specific treatment, but the patient should be reassured that the hemorrhage will disperse in 2–3 weeks, with blood turning from red to brown and then to yellow ().Citation1,Citation2

Figure 4 An island of yellow discoloration on the nasal part of the bulbar conjunctiva indicating absorption of the subconjunctival hemorrhage.

There is not any approved treatment to accelerate the resolution and absorption of SCH. The first treatment reported in the literature was air therapy.Citation74 A patient with a severe SCH caused by acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis was treated with nasal and temporal subconjunctival injection of tissue plasminogen activator.Citation75 SCH was a new area of usage for tissue plasminogen activator alongside its use in vitreous, anterior chamber, and glaucoma filter bleb to induce the clearance of fibrin clots.Citation76–Citation78 Moon et alCitation79 evaluated the effect of subconjunctival injection of liposome-bound, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) on the absorption rate of SCHs in rabbits. The report concluded that the subconjunctival injection of liposome-bound LMWH had a significant influence on facilitating SCH absorption in rabbits in comparison to only liposome and liposome-free form of LMWH.Citation79 Another two forms of the same molecule – liposome-encapsulated streptokinase and free-form streptokinase – were injected into the subconjunctival area to enhance the rate of SCH absorption in rabbits by Baek et al,Citation80 and they found that SCH absorption rate in the liposome-capsulated form was faster than the free-form streptokinase injection group, particularly in the early phases, which were described as 24–48 hours after SCH induction.

Failure to resolve hemorrhage in persistent or recurrent cases suggests a serious underlying cause. A careful history is the most important step in identifying whether there is a serious underlying condition that may require more detailed examination and treatment. A detailed history may provide clues to the underlying conditions. It is important to obtain a thorough medication, medical, and ocular history from patients presenting with SCH, including any possible trauma, ocular surgery, contact lens wear, drugs, and heritable conditions. First, a careful slit-lamp examination is essential to determine if there has been any trauma to the eye, and also to rule out any local ocular condition that can lead to SCH, as mentioned previously. After excluding ocular factors, further systemic evaluation is necessary. Blood pressure should be checked routinely in all patients with SCH, particularly in older patients. In recurrent cases, a workup for bleeding disorders and hypocoagulable states is required. The INR should be checked if the patient is taking warfarin.

In conclusion, only recurrent or persistent SCH mandates further systemic evaluation, and no treatment is required unless it is associated with certain serious conditions.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest and no commercial interests in any products or services used in this study.

References

- LeibowitzHMThe red eyeN Engl J Med2000343534535110922425

- Duke-ElderSConjunctival diseasesSystem of Ophthalmology Diseases of the Outer EyeLondonHenry Kimpton1965VIII3439

- YanoffMFineBSConjunctivaOcular PathologyMaryland Heights (MO)Mosby1996206207

- MimuraTYamagamiSUsuiTLocation and extent of subconjunctival hemorrhageOphthalmologica20102242909519713719

- FukuyamaJHayasakaSYamadaKSetogawaTCauses of subconjunctival hemorrhageOphthalmologica1990200263672338986

- MimuraTUsuiTYamagamiSRecent causes of subconjunctival hemorrhageOphthalmologica2010224313313719738393

- KingABWalshFBTrauma to the head with particular reference to the ocular signs; injuries involving the hemispheres and brain stem; miscellaneous conditions; diagnostic principles; treatmentAm J Ophthalmol194932337939818112994

- AsbellPADeLuiseVPBartolomeiAViral conjunctivitisTabbaraKFHyndiukRAInfections of the EyeBostonListen Brown1996462463

- ChiuCHChuangYYSiuLHSubconjunctival haemorrhage and respiratory distressLancet2001358928372411551580

- SklarVEPatriarcaPAOnoratoIMClinical findings and results of treatment in acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis in Southern FloridaAm J Ophthalmol198395145546849368

- BhatiaVSwamiHMAn epidemic of acute haemorrhagic conjunctivitis in school childrenIndian J Pediatr199966115815910798053

- KayikçiogluOKirESöylerMGülerCIrkeçMOcular findings in a measles epidemic among young adultsOcul Immunol Inflamm200081596210806435

- Gaver-ShavitAMinouniMSubconjunctival hemorrhage in chickenpoxPediatr Infect Dis J19911032532542041675

- ShieldsCLShieldsJATumors of the conjunctiva and corneaSurv Ophthalmol200449132414711437

- ShieldsJAMashayekhiAKligmanBEVascular tumors of the conjunctiva in 140 casesOphthalmology201111891747175321788081

- KiratliHUzunSTarlanBTanasÖRecurrent subconjunctival hemorrhage due to cavernous hemangioma of the conjunctivaCan J Ophthalmol201247331832022687315

- TongJWSawamuraMHSubconjunctival hemorrhages: presenting sign for hereditary hemochromatosisOptom Vis Sci20118891133113921666526

- MimuraTUsuiTYamagamiSSubconjunctival hemorrhage and conjunctivochalasisOphthalmology2009116101880188619596440

- LiuWLiHQiaoJThe tear film characteristics of spontaneous subconjunctival hemorrhage patients detected by Schirmer test I and tear interferometryMol Vis2012181952195422876120

- WellsAPMarksJKhawPTSpontaneous inferior subconjunctival hemorrhages in association with circumferential drainage blebsEye (Lond)200519326927215184967

- SchmitzJConjunctivochalasis and subconjunctival hemorrhageOphthalmology201011712244421129575

- BrownsteinMHElliottRHelwigEBOphthalmologic aspects of amyloidosisAm J Ophthalmol19706934234305418860

- SmithMEZimmermanLEAmyloidosis of the eyelid and conjunctivaArch Ophthalmol196675142515900504

- LeeHMNaorJDeAngelisDRootmanDSPrimary localized conjunctival amyloidosis presenting with recurrence of subconjunctival hemorrhageAm J Ophthalmol2000129224524710682979

- Cheong-LeenRPrimary localised conjunctival amyloidosis presenting as subconjunctival haemorrhageEye (Lond)200115567968011702995

- HigginsGTOlujohungbeAKyleGRecurrent subconjunctival and periorbital haemorrhage as the first presentation of systemic amyloidosis secondary to myelomaEye (Lond)200620451251515905867

- FelipeAFNottageJMRapuanoCJRecurrent bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage as an initial presentation of multiple myelomaOman J Ophthalmol20125213313422993476

- RothHWPathologic findingsContact Lens ComplicationsNew YorkThieme20034244

- MimuraTYamagamiSFunatsuHContact lens-induced subconjunctival hemorrhageAm J Ophthalmol2010150565666520709310

- CarterKMillerKMPhacoemulsification and lens implantation in patients treated with aspirin or warfarinJ Cataract Refract Surg19982410136113649795852

- LalchanSASpontaneous hyphaema and intra-bleb subconjunctival haemorrhage in a patient with previous trabeculectomyEye (Lond)200620785385416138116

- GuisePASub-Tenon anesthesia: a prospective study of 6,000 blocksAnesthesiology200398496496812657860

- RomanSJChong SitDABoureauCMAuclinFXUllernMMSub-Tenon’s anaesthesia: an effect and safe techniqueBr J Ophthalmol19978186736769349156

- CalendaELamotheLGenevoisOCardonAMuraineMPeribulbar block in patients scheduled for eye procedures and treated with clopidogrelJ Anesth201226577978222581096

- KatzJFeldmanMABassEBStudy of medical testing for cataract surgery teamRisks and benefits of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication use before cataract surgeryOphthalmology200311091784178813129878

- MorrisAElderMJWarfarin therapy and cataract surgeryClin Experiment Ophthalmol200028641942211202464

- RobinsonGANylanderAWarfarin and cataract extractionBr J Ophthalmol19897397027032804024

- NodaSHayasakaSRecurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages in patients with Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitisOphthalmologica199520952892918570156

- KumarRAMoturiKSubconjunctival ecchymosis after extraction of maxillary molar teeth: a case reportDent Traumatol201026329830020406279

- KaraCOKaraIGYaylaliVSubconjunctival ecchymosis due to rhinoplastyRhinology200139316616811721509

- AkhaddarABoucettaMSubconjunctival hemorrhage as a complication of intraoperative positioning for lumbar spinal surgerySpine J201212327422364948

- RajvanshiPMcDonaldGBSubconjunctival hemorrhage as a complication of endoscopyGastrointest Endosc200153225125311174311

- RodgersIRJakobiecFAGingoldMPHornblassAKrebsWAnaplastic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland presenting with recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages and displaying incipient sebaceous differentiationOphthal Plast Reconstr Surg199174229237

- HicksDMickARecurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages leading to the discovery of ocular adnexal lymphomaOptometry2010811052853220705524

- KittisupamongkolWBlood pressure in subconjunctival hemorrhageOphthalmologica2010224533220431313

- GondimFALeacockROSubconjunctival hemorrhages secondary to hypersympathetic state after a small diencephalic hemorrhageArch Neurol200360121803180414676062

- PittsJFJardineAGMurraySBBarkerNHSpontaneous subconjunctival haemorrhage – a sign of hypertension?Br J Ophthalmol19927652972991390514

- SpitzerSGLuornoJNoëlLPIsolated subconjunctival hemorrhages in nonaccidental traumaJ AAPOS200591535615729281

- DeRidderCABerkowitzCDHicksRALaskeyALSubconjunctival hemorrhages in infants and children: a sign of nonaccidental traumaPediatr Emerg Care201329222222623546430

- Rodriguez-RoisinRTorresAAgustíAGUssettiPAgustí-VidalASubconjunctival haemorrhage: a feature of acute severe asthmaPostgrad Med J19856175795814022890

- PaysseEACoatsDKBilateral eyelid ecchymosis and subconjunctival hemorrhage associated with coughing paroxysms in pertussis infectionJ AAPOS19982211611910530974

- ChowLYLeeJSLeungCMVoluntary breath-holding leading to bilateral subconjunctival haemorrhaging in a patient with schizophreniaHong Kong Med J201016323220519763

- SodhiPKJoseRSubconjunctival hemorrhage: the first presenting clinical feature of idiopathic trombocytopenic purpuraJpn J Ophthalmol200347331631812782172

- Taamallah-MalekIChebbiABouladiMNacefLBouguilaHAyedSMassive bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage revealing acute lymphoblastic leukemiaJ Fr Ophtalmol2013363e45e48 French23122838

- BenzimraJDJohnstinRLJaycockPThe Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55,567 operations: antiplatelet and anticoagulant medicationsEye (Lond)2009231101618259210

- BodackMIA warfarin-induced subconjunctival hemorrhageOptometry200778311311817321459

- NguyenTMPhelanMPWerdichXQRychwalskiPJHuffCMSubconjunctival hemorrhage in a patient on dabigatran (Pradaxa)Am J Emerg Med2013312445. e3e5

- LeikerLLMehtaBHPruchnickiMCRodisJLRisk factors and complications of subconjunctival hemorrhages in patients taking warfarinOptometry200980522723119410227

- ChijiokeAUremic bleeding with pericardial and subconjunctival hemorrhageSaudi J Kidney Dis Transpl20112261246124822089795

- ParmeggianiFCostagliolaCIncorvaiaCPrevalence of factor XIII Val34Leu polymorphism in patients affected by spontaneous subconjunctival hemorrhageAm J Ophthalmol2004138348148415364237

- IncorvaiaCCostagliolaCParmeggianiFGemmatiDScapoliGLSebastianiARecurrent episodes of spontaneous subconjunctival hemorrhage in patients with factor XIII Val34Leu mutationAm J Ophthalmol2002134692792912470774

- HainesSTRacineEZeollaMVenous thromboembolismDiPiroJTTalberRLYeeGCMatzkeGRWellsBGPoseyLMPharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach5th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill2002337373

- BodackMIA warfarin-induced subconjunctival hemorrhageOptometry200778311311817321459

- SupersteinRGomolinJEHammoudaWRosenbergAOverburyOArsenaultCPrevalence of ocular hemorrhage in patients receiving warfarin therapyCan J Ophthalmol200035738538911192447

- KatoTWatanabeKKatoriMTeradaYHayasakaSConjunctival injection, episcleral vessel dilation, and subconjunctival hemorrhage in patients with new tsutsugamushi diseaseJpn J Ophthalmol19974131961999243318

- DassRDekaNMDuwarahSGCharacteristics of pediatric scrub typhus during an outbreak in the North Eastern region of India: peculiarities in clinical presentation, laboratory findings and complicationsIndian J Pediatr201178111365137021630069

- LinCYChiuNCLeeCMLeptospirosis after typhoonAm J Trop Med Hyg201286218718822302844

- ThapaRBanerjeePJainTSBilateral subconjunctival haemorrhage in childhood enteric feverSingapore Med J200950101038103919907900

- HayasakaSFujiiMYamamotoYNodaSKuromeHSasakiMRetinopathy and subconjunctival haemorrhage in patients with chronic viral hepatitis receiving interferon alfaBr J Ophthalmol19957921501527696235

- AndradeRJGonzálezFJVázquesLVascular ophthalmological side effects associated with antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C are related to vascular endothelial growth factor levelsAntivir Ther200611449149816856623

- RazeghinejadMRTehraniMJSudden onset and blinding spontaneous direct carotid-cavernous fistulaJ Ophthalmic Vis Res201161505322454707

- PongJCLamDKLaiJSSpontaneous subconjunctival haemorrhage secondary to carotid-cavernous fistulaClin Experiment Ophthalmol2008361909118290959

- LiLHLiNZhaoJYFindings of perinatal ocular examination performed on 3573, healthy full-term newbornsBr J Ophthalmol201397558859123426739

- RichardsRDSubconjunctival hemorrhage: treatment with air therapyEye Ear Nose Throat Mon1965445914338027

- MimuraTYamagamiSFunatsuHManagement of subconjunctival haematoma by tissue plasminogen activatorClin Experiment Ophthalmol200533554154216181290

- LambrouFHSnyderRWWilliamsGALewandowskiMTreatment of experimental intravitreal fibrin with tissue plasminogen activatorAm J Ophthalmol198710466196233120591

- LambrouFHSnyderRWWiliamsGAUse of tissue plasminogen activator in experimental hyphemaArch Ophthalmol198710579959973111453

- SzymanskiAPromotion of glaucoma filter bleb with tissue plasminogen activator after sclerotomy under a clotInt Ophthalmol1992164–53873901428577

- MoonJWSongYKJeeJPKimCKChoungHKHwangJMEffect of subconjunctivally injected, liposome-bound, low-molecular-weight heparin on the absorption rate of subconjunctival hemorrhage in rabbitsInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20064793968397416936112

- BaekSHParkSJJinSEKimJKKimCKHwangJMSubconjunctivally injected, liposome-encapsulated streptokinase enhances the absorption rate of subconjunctival hemorrhages in rabbitsEur J Pharm Biopharm200972354655119362145