Abstract

Dry eye disease (DED) has a higher prevalence than many important systemic disorders like cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, representing a significant quality of life burden for the affected patients. It is a common reason for consultation in general eye clinics worldwide. Nowadays, the diagnostic and therapeutic approach at the high corneal and ocular surface specialty level should be reserved for cases of severe and chronic dry eye disease associated with systemic autoimmune diseases or complicated corneal and ocular surface pathologies. In such cases, the diagnostic and therapeutic approach is often complex, elaborate, time-consuming, and costly due to the use of extensive dry eye questionnaires, noninvasive electronic diagnostic equipment, and clinical laboratory and ancillary tests. However, other eye care specialists attend a fair amount of DED cases; therefore, its diagnosis, classification, and management should be simple, practical, achievable, and effective. Considering that many patients attending non-specialized dry eye clinics would benefit from better ophthalmological attention, we decided to elaborate a practical DED classification system based on disease severity to help clinicians discriminate cases needing referral to subspecialty clinics from those they could attend. Additionally, we propose a systematic management approach and general management considerations to improve patients’ therapeutic outcomes according to disease severity.

Plain Language Summary

The Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel consists of an academic representative group of Cornea and Ocular Surface specialists concerned about the progressive growth of dry eye symptoms and significant ocular surface changes increasingly affecting more and more age groups of the general population. The panel is devoted to improving the early recognition and classification of dry eye disease and the efficacious management of patients suffering from the condition. Currently, there are exhaustive literature reports on the classification and management of dry eye disease, and although the amount of knowledge contribution is immense, few reports focus on a practical approach for eye care clinicians who are dealing with these patients for the first time on an everyday basis. The present report aims to propose a practical and straight-forward systematic methodology for the early detection, practical classification, and effective management of patients suffering from any form of dry eye disease. We have compiled the essential concepts from the National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop, the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop reports, the ODISSEY European Consensus group, the Japan Dry Eye Society, the Asia Dry Eye Society, and the Italian Dacryology & Ocular Surface Society, among other relevant reports to formulate our proposal. We hope that this effort will represent a useful diagnostic and therapeutic tool for eye care specialists in caring for patients with this common disorder.

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is a common multifactorial disorder affecting the ocular surface through loss of the homeostasis of the tear film.Citation1 It is accompanied by many symptoms, including burning, dryness and foreign body sensation, and visual fluctuation that interfere significantly with everyday activities such as reading, driving, watching television, and viewing electronic devices with a digital screen.Citation2,Citation3

The lack of a consistent diagnostic criteriaCitation4 and environmental,Citation5,Citation6 geographical,Citation7 demographic,Citation8 and racial differences,Citation9 present across multiple population-based epidemiological studies render estimating the precise DED prevalence difficult.Citation10 Furthermore, DED prevalence varies, depending on its definition and whether symptoms (4.9–52.9%), signs (6.0–98.5%), or both (8.7–30.1%) are considered for diagnosis.Citation10 A recent population-based cross-sectional survey study projected that 6.8% of US adults have DED.Citation8 Prevalence was higher among women (8.8% vs 4.5%) than men and increased from 2.7% in adults aged 18–34 years to 18.6% in those aged 75 years or older.Citation8 Papas recently modeled the prevalence of relevant DED studies (n = 55) reporting prevalence between 1997–2021 as a Beta distribution and, within the framework of a Bayesian approach, reported an estimated global DED prevalence of 11.59%.Citation11

Evidence regarding the prevalence of DED in the Mexican population is limited. Graue-Hernandez et al reported an overall prevalence of dry eye symptoms in 41.1% of adults aged 50 or older.Citation12 Women, individuals with a history of smoking or alcohol consumption, and those under systemic antihypertensive therapy were at significantly higher risk of DED.Citation12 Martinez et al reported a 43% prevalence of severe dry eye symptoms among individuals aged 16 years or more living in Mexico City.Citation13 The authors reported aqueous (ADDE, Schirmer ≤5mm/5min) and evaporative tear deficiency [EDE, tear film breakup time (TFBUT) ≤5s] in 22% and 94% of participants included, respectively.Citation13 Rodriguez-Garcia et al reported a 63% prevalence of DED in a population-based study that included patients from 10 Mexican states.Citation3 The authors found the prevalence of positive corneal fluorescein staining (CFS) increased from 66% to 92% depending on whether patients seek ophthalmological attention with one or ≥4 eye complaints, respectively.Citation3

The humanitarian and economic burden of DED in Europe, North America, and Asia between January 1998 and July 2013 were exhaustively reviewed by McDonald et al.Citation14 They evaluated the economic cost and the health-related quality of life (QoL) of DED comparing the evidence across France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States, Japan, and China.Citation14 According to the analysis, the available evidence, although limited, suggests that DED affects physical and psychological functions; hence, the QoL, resulting in significant humanistic affliction on patients.Citation14 The same holds for the economic cost derived from poor labor performance or absence from work due to medical consultations and their costs and medications.Citation14 Aside from the negative impact of DED on the QoL of individuals, it represents a $55 billion annual burden to the United States economy.Citation15 Data evaluating the economic burden of DED in Mexico are currently unavailable. Thus, studies evaluating the latter are required to improve future resource utilization.

Due to the rising incidence of DED and its various diagnostic factors, it is essential to determine its severity to manage it appropriately. This report aims to provide eye care specialists with a reliable, helpful, and practical tool to classify the severity of DED to optimize the treatment algorithm. DED severity classification is essential as a guide for diagnosis and treatment, allowing a personalized DED treatment for each patient and monitoring the therapeutic response.

Basic Concepts on Dry Eye Disease

Development of the Definition of Dry Eye Disease

The Industry Workshop on Clinical Trials in DED, held in 1995 under the auspices of the National Eye Institute (NEI), shaped the first formal definition of DED.Citation16 Three major concepts are inherent to this definition, (1) the recognition that an abnormal tear film is the primary pathophysiological mechanism of DED; (2) the pathology arises from either an aqueous deficiency or excessive tear film evaporation; and (3) DED causes discomfort symptoms”.Citation1,Citation16 This report established a solid foundation that launched translational, clinical, and basic scientific research to improve the diagnosis and treatment.Citation1 However, the NEI workshop DED definition was incomplete, lacking critical aspects of the pathogenesis and symptomatology of the disease.

Due to the growing evidence concerning diagnosis and therapeutics of dry eye, the first Tear Film & Ocular Surface Dry Eye Workshop (TFOS DEWS) held in 2007 proposed a definition including its multifactorial origin, the increase in tear osmolarity, and inflammation of the ocular surface as crucial pathogenic findings,Citation17,Citation18 and the presence of visual disturbances among relevant symptoms.Citation19 This definition recognized dry eye as a disease, resulting from a complex abnormal interaction between the tear film and the ocular surface, suggesting that DED results from an alteration in ≥1 portions of the intertwined “functional unit” comprised by the conjunctiva, cornea, accessory lacrimal and Meibomian glands, the main lacrimal gland, eyelids, and motor and sensory nerves.Citation20,Citation21

The TFOS DEWS II (2017) produced an evidence-based definition, recognizing the loss of tear film homeostasis as the conveying element in DED, reasserting ocular symptoms as the central feature of DED, and expanding the pathophysiological understanding of the disease by adding the neurosensory abnormalities.Citation1,Citation22 However, this definition does not account for differences in symptom duration.Citation20 For example, although patients with DED associated with Sjögren syndrome and those with recent refractive surgery may present similar dry eye symptoms, the former is unlikely to improve over time, while the latter is expected to exhibit significant improvement.Citation20

Pathophysiology of Dry Eye Disease

The primary mechanism of DED is evaporation-induced tear hyperosmolarity, which damages the ocular surface directly and by initiating inflammation.Citation23 The pathogenic cycle of events triggered in dry eye is known as “the vicious circle of DED”.Citation24 A fall in lacrimal secretion (ADDE) or an increase in evaporation from the tear film (EDE) induces hyperosmolarity. A combination of these two mechanisms (mixed type) is the most recognized form of DED. Since tear hyperosmolarity arises from tear evaporation in both ADDE and EDE; therefore, all forms of DED have an evaporative component. In addition, the rise in osmolarity prompts the release of inflammatory mediators, thus triggering an inflammatory process.Citation23 The tear osmolarity threshold values vary from 308 to 316 mOsm/L.Citation24,Citation25 A study performed by Versura et al reported a 98.4% positive predictive value for DED using a tear osmolarity threshold value of 305 mOsm/L.Citation26 To date, tear film osmolarity is considered the most sensitive individual measure.Citation27 A value of 308 mOsm/L is widely accepted as the threshold, whereas 316 mOsm/L is suspected to better distinguish between mild and moderate/severe DED.Citation17,Citation27 Furthermore, the tears’ hyperosmolarity is considered as a triggering mechanism for a cascade of signaling events within surface epithelial cells, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines and proteases,Citation28 which in turn, disturbs the mucin-expressing glycocalyx, induces goblet cells’ apoptosis, resulting in damage to the corneal and conjunctival epithelium.Citation29 At the same time, inflammatory mediators from activated T-cells are recruited to the ocular surface, reinforcing the damage.Citation30 These sequential events result in punctate epitheliopathy and tear film instability due to inflammatory changes leading to thickening and stasis of the meibum, blockage of the Meibomian glands’ distal excretory ducts, and shortness of the tear film breakup time. The latter exacerbates and increases tear hyperosmolarity, completing the negative vicious cycle that leads to ocular surface damage and self-perpetuation of the disease.Citation31

Risk Factors for Dry Eye Disease

Due to the multifactorial nature of DED, multiple risk factors are associated with disease development.Citation32 Significant risk factors for dry eye disease according to a large population-based study (Beaver Dam Eye Study), included age, female gender, history of arthritis, smoking status, caffeine use, history of gout and thyroid disease, a total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, diabetes mellitus, and multivitamin use.Citation32 Other relevant risk factors for DED reported are alcohol consumption,Citation12 topical anti-glaucoma and preserved eye drops,Citation3 and systemic medications (ie, antihistamines, antidepressants, antihypertensives, diuretics, among others).Citation33 Environmental factors including air contamination, exposure to dry air, a high altitude, and use of electronic visual displays are also considered risk factors for DED.Citation5,Citation6,Citation34

Dry Eye Disease Classification Systems

In the following subsections, we will briefly discuss other DED definitions and classification systems proposed by other authors. As the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel, other authors have suggested DED classification systems based on severity. Some of those systems are summarized in .Citation35–Citation39

Table 1 Dry Eye Disease Classification Systems Based on Severity

National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop

The NEI/Industry Workshop report proposed two broad classifications of dry eye: ADDE and EDE.Citation16 The former was further sub-classified as Sjögren syndrome, either primary or secondary, or non-Sjögren tear deficiency, which included abnormalities in the lacrimal system.Citation16 EDE was sub-classified according to oil deficiency, lid-related abnormalities (ie, blink, aperture, congruity), use of contact lens, and surface changes.Citation16 As stated before, this classification system fails to provide insights regarding pathophysiological mechanisms, vision-related abnormalities associated with dry eyes, and the value of assessing disease severity.Citation37 Moreover, it neglects the internal (ie, age, systemic drug use) and external (ie, relative humidity, pollution) effect of the environment in the pathogenesis of dry eyes.Citation40,Citation41

The Tear Film & Ocular Society Dry Eye Workshop

In their 2007 report, the proposed TFOS DEWS I classification system maintained the ADDE and EDE categories proposed by the NEI/Industry Workshop.Citation37 However, they readdressed the vague concept of “tear deficient” to the more specific “aqueous-deficient” term.Citation37 This system also included environmental conditions encountered by individuals, named the milieu exterieur, and the physiologic differences between them (milieu interieur).Citation37 The severity grading scheme established four levels of dry eye based on ocular discomfort and visual symptoms and the presence of multiple signs, including conjunctival, corneal, lid/meibomian gland, TFBUT, and Schirmer scores.Citation37 Although the definition of DED provided by the TFOS DEWS I was significantly improved in newer knowledge of the pathogenesis and impact on vision, the classification scheme was essentially unchanged.Citation21,Citation39,Citation40

The current classification system, proposed by the TFOS DEWS II in 2017, comprises a clinical decision algorithm based on the current understanding of DED pathophysiology. It first categorizes patients as asymptomatic or symptomatic, then further as symptomatic with no signs, asymptomatic with signs, neurotrophic (dysfunctional sensation), with neuropathic pain or other known causes of ocular surface disease, and as ADDE, EDE, or mixed.Citation1 This classification scheme recognizes that there is no clear cut between EDE and ADDE, and thus, they exist as a spectrum rather than separate diseases.Citation1

The ODISSEY European Consensus Group

In 2014, the ODISSEY European Consensus Group (OECG) proposed a stepwise algorithm that facilitates DED diagnosis even with symptoms and signs of discordance.Citation30 The panel discussed the utility of 14 different criteria, including CFS, tear hyperosmolarity, Schirmer test, IC, conjunctival staining, and visual function impairment. Also, Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) or lid inflammation, blepharospasm, filamentary keratitis, TFBUT, aberrometry, in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), DED refractory to standard treatments, and presence of inflammatory biomarkers, including matrix metalloproteinase-9, cytokines, and tear proteomics, for diagnosing severe DED ().Citation30

The Japan Dry Eye Society

The Japan Dry Eye Society (JDES) established their first DED definition and diagnostic criteria in 1995,Citation42 the same year the NEI/Industry Workshop published their first report.Citation16 The JDES defined DED as the “ocular surface epithelial damage caused by qualitative or quantitative abnormalities of tears”.Citation42 This definition suggests (1) tear abnormalities are culprits of damage to the ocular surface epithelia, (2) it does not include the subjective symptoms experienced by patients, and (3) it fails to include the role of external and internal factors leading to DED.Citation42 DED diagnosis was made if tear abnormalities (Schirmer test-I ≤5mm/5min and TFBUT ≤5s) and ocular surface staining with vital dyes were present.Citation42

In 2006, the JDES updated their previous DED definition after recognizing ocular surface damage and tear abnormalities were reciprocal, thus forming a vicious cycle.Citation43 Moreover, they included the role of intrinsic and extrinsic variables potentially leading to DED development, including MGD, contact lens wear, among others. They also included the potential of DED to cause irritative symptoms and visual disturbances.Citation43 Diagnostic criteria were similar; however, they included subjective symptoms in the current workshop.Citation43 In 2012, the Asia Dry Eye Society (ADES), including DED experts from China, Korea, and Japan (aka, the JDES), was established.Citation44 Five years later, after the society reached a final consensus, their DED definition was published (See Next Section).Citation44

The Asia Dry Eye Society

The ADES definition keeps the multifactorial etiopathogenic character of DED, the unstable tear film concept causing various symptoms and visual impairment, and consequently incorporates ocular surface damage.Citation40 The ADES DED classification is based on the concept of a tear film-oriented diagnosis, suggesting there are three types of dry eye: (1) aqueous-deficient, (2) increased evaporation, and (3) decreased wettability. According to this classification, the three DED types correspondingly coincide with problems at each layer of the tear film. Although each component cannot be quantitatively evaluated with the current technology, a practical diagnosis based on the patterns of fluorescein disruption is recommended.Citation40

The ADES classification is helpful for the concept of tear film-oriented therapy. It is based primarily on problems with each layer of the tear film and the surface epithelium; however, the tear film changes observed in DED do not occur exclusively in a particular layer but rather in different combinations and degrees of severity. This group recommends using fluorescein dye, available to any eye care specialist contributing to an effective DED diagnosis and treatment,Citation40 instead of using an interferometer, an expensive electronic device with limited availability at most eye care specialists’ clinics, requiring trained operators.Citation45 The ADES did not provide a severity classification for DED, arguing that, since there is no correlation between signs and symptoms severity (neuropathic pain), a severity scheme lacks therapeutic utility.Citation40

The Italian Dacryology & Ocular Surface Society Classification

This DED classification system is based on a consensus reached by the Italian Dacryology & Ocular Surface Society (Società Italiana di Dacriologia e Superficie Oculare, SIDSO) using Delphi and nominal group techniques.Citation39 They propose three DED severity categories based on the ocular surface capacity to restore homeostasis, symptoms frequency, the presence of inflammation, epithelial changes, and any other changes in quality of vision (). The SIDSO introduced an exciting concept of ocular surface tissue restoration capacity (See Discussion).Citation39

The Need for a Practical and Straightforward Classification System Based on the Severity of Dry Eye Disease in Latin America

Although our understanding of DED has significantly evolved over the last two decades, no single classification system categorizes properly every individual with DED.Citation20 The hindmost, due to the multifactorial nature and multiple risk factors underlying DED.Citation46 These are reasons why some authors question the TFOS DEWS II definition and classification criteria, suggesting it fails to capture the intrinsic heterogeneity of DED patients, preventing its applicability to every patient.Citation20 Moreover, the TFOS DEWS II criteria, although exquisitely detailed from the theoretical point of view, makes little reference to day-by-day clinical practice.Citation39 Given the multiple suggestions for a DED classification system, identifying the etiology and the extension or severity of the disease is crucial for treatment selection and monitoring disease progression.

Considering the need to involve the most eye care specialists possible dealing with DED patients and following the initiative to create a simple, practical, and low-cost classification methodology, the expert panel agreed to exclude noninvasive imaging DED diagnostic modalities from the severity classification.Citation21,Citation42,Citation43 Although the value of noninvasive DED studies, particularly for diagnosis standardization and therapy monitoring, is unquestionable, meaning they should be used whenever available, they are costly, time-consuming, and not readily available for every patient with dry eye. Furthermore, we are convinced that the proposed standard clinical tests for dry eye will correctly classify DED severity and help clinicians propose a therapeutic approach accessible to the entire population.

As stated before, no studies evaluating the economic burden of DED in Mexico are available; however, Mexico, a low-income country, has limited coverage and access to health services.Citation47 Moreover, there is a deficit of eye care specialists in Mexico, with only 42.5 ophthalmologists per million habitants, significantly lower than other countries such as Germany (90.5 per million) or France (92.0 per million).Citation48 As such, optimizing care and reducing costs in Mexican DED patients by efficiently establishing diagnosis and treatment seems reasonable and necessary. With such conditions in mind, the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel has proposed a simplified and practical classification system based on DED severity that any eye care specialist could use without the need for complicated, time-consuming, and costly clinical tests.

Materials and Methods

A total of eight Mexican cornea and ocular surface specialists with a leader opinion profile comprised the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel. A roundtable discussion approach was used to reach a consensus on the DED diagnostic classification and therapeutic guidelines. Other eye care specialists have used a similar approach in previous studies to reach consensus in a myriad of eye pathologies, including DED,Citation23,Citation30,Citation49 graft-versus-host disease (GvHD),Citation50 and limbal stem cell deficiency.Citation51

A total of five consecutive online meetings were held between March 2021 and July 2021 via Teams (version 1.4.00.11161, 2011. Microsoft® Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) to discuss and reach a consensus on proposing a practical approach to classify (according to disease severity) and give treatment guidelines for DED patients. Multiple votes for the possible decisions with the highest scoring options going to voting rounds were used to obtain a consensus. Ranking was also applied to find out to what degree the group preferences converged in specific classification methods and therapeutic alternatives for DED.

After reaching a consensus, the classification criteria based on DED severity were formulated considering utility, efficiency, and cost. The experts’ panel also agreed on the DED severity score. After that, therapeutic recommendations and guidelines were drawn following the same line of thought. Results were summarized by the senior author (ARG) at the last meeting and sent via email to all members for approval.

Results

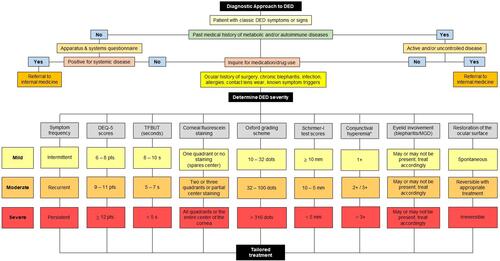

After a thorough review of the current DED knowledge, voting results, discussions, and analyses, the Mexican Dry Eye Expert Panel proposes two algorithms to classify DED according to the severity and establish management following the former.

The Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel Proposed Classification Criteria for Dry Eye Disease Severity

There are a great variety of qualitative and quantitative, invasive, and non-invasive clinical tests to assess the symptoms and signs of DED. Most of these tests have reasonable diagnostic levels of sensitivity and specificity.Citation25,Citation52–Citation54 Apart from diagnosis purposes, performing such tests in each patient allows finding the significance of the patient’s symptomatology, including the QoL and the amount of damage to the ocular surface and its visual implications.Citation55,Citation56 Therefore, combining the most relevant and practical diagnostic tests would also permit DED classification according to severity.

Determinant Criteria

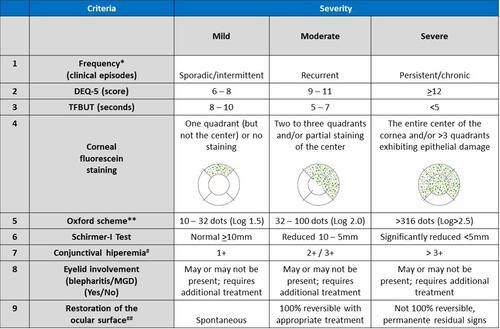

The principles for test selection by the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel were their diagnostic ability, minimal invasiveness, objectivity, practicality, and clinical applicability. Nine criteria were considered and discussed herein ().Citation39,Citation54,Citation57,Citation58 First, it is necessary to establish a DED diagnosis in a patient with either classic dry eye symptoms or signs. outlines the consensus severity classification criteria proposed by the Mexican Panel for DED. Also, we provide a systematic diagnostic workflow to approach DED patients ().

Table 2 Consensus Criteria for Classification of Dry Eye Disease

Figure 1 Dry eye disease classification criteria proposed by the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel.

Figure 2 Stepwise diagnostic approach for dry eye disease.

Frequency and Duration of Symptoms

The presence of ocular symptoms, including visual disturbances, must be evaluated independently from the severity of signs. The latter since there is compelling evidence suggesting a potential lack of correlation between the severity of symptoms and signs in DED.Citation38 Also, the frequency (ie, intermittent, recurrent, or persistent) of symptoms must be inquired.Citation20

Dry Eye Questionnaires

Symptoms and other subjective reports such as the international classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome from the American-European Consensus Group (AECG),Citation59 are captured in the patient’s clinical history; however, such data are difficult to quantify in a standardized format. Therefore, a validated symptom questionnaire should be administered during the patient’s first visit. Such survey instruments use directed and specific questions for dry eye to enhance standardization and are self-administered by the patient without influence from the clinician or researcher.Citation4 These instruments can measure different aspects of DED, including ocular surface discomfort, visual symptoms, and health related QoL. If a given patient has a high score in any validated dry eye questionnaire, a more in-depth investigation of the clinical signs of DED is mandatory.Citation57 summarizes the most frequently used DED questionnaires in clinical practice.Citation57,Citation60–Citation67

Table 3 Frequently Used Dry Eye Disease Questionnaires in Clinical Practice

Although the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) is the most widely used questionnaire for DED clinical trials, measuring symptoms frequency, environmental triggers, and vision-related QoL, it takes longer to answer and may require assistance to do so.Citation62 The consensus view of the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel is that the Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ)-5 is an excellent alternative for busy eye care practices because it takes a shorter time to answer, has an excellent discriminative ability, and is validated to the Spanish language for use among the Mexican population.Citation60

Tear Film Breakup Time

TFBUT is used to assess tear film stability and is helpful for diagnosing and therapeutic monitoring patients with dry eyes.Citation52,Citation53,Citation68–Citation70 Compared to non-invasive tests using electronic devices, fluorescein remains the most widely used method among eye care specialists for assessing dry eye, including researchers at the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA),Citation71 and is recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern, Cornea and External Disease Panel.Citation72 Several studies suggest no significant difference in TFBUT measured using fluorescein strips vs controlled volumes of liquid dye.Citation73 TFBUT is especially useful for assessing and diagnosing MGD and EDE ().Citation74 A TFBUT ≥10s is considered normal, although this depends on the blinking interval time,Citation75 which is influenced by numerous factors such as environmental conditions, air circulation and convection, corneal sensitivity, and level of attention.Citation75,Citation76

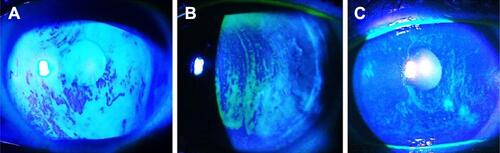

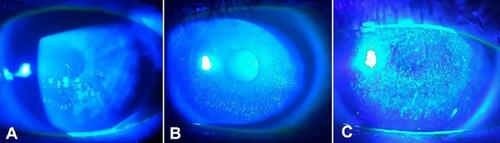

Figure 3 Different patterns of TFBUT at different time elapsed after blinking in patients with (A) staphylococcal blepharitis, (B) MGD, and (C) Sjögren syndrome with associated MGD.

Although noninvasive TFBUT measurements are expensive and not readily available for all patients, overwhelming evidence supports their use. Thus, we felt it necessary to emphasize that, if available, eye care specialists must consider its use. While conventional TFBUT measurement, with a cut-off value of ≤10s, yields a 72% sensitivity and 39% specificity,Citation77 noninvasive TFBUT measurement ranges from 82–84% and 76–94%, respectively.Citation4

Ocular Surface Staining

The degree of ocular surface staining after the instillation of fluorescein or vital stains like sodium fluorescein, lissamine green, or rose Bengal is a critical diagnostic component of dry eye assessment. Punctate staining of the corneal and conjunctival epithelia is a feature of many disorders, and ocular surface staining is used extensively in diagnosing and managing DED.Citation78 In addition, the staining pattern may provide an etiological clue. The most frequently used vital dyes are rose bengal and lissamine green. Positive staining occurs whenever epithelial cell viability is lost, disrupted superficial cell tight junctions, or a defective glycocalyx. After dye instillation on the ocular surface, slit-lamp examination using a red-free light for rose bengal or standard white light for lissamine green staining is performed.Citation71,Citation78

Corneal Fluorescein Staining

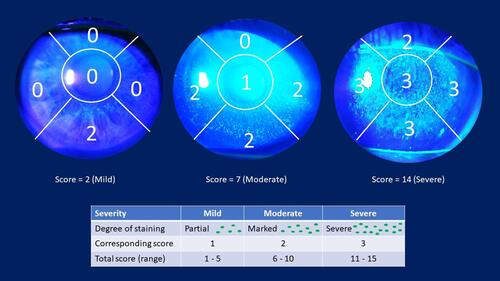

CFS test assesses the corneal epithelium integrity. After shaking off saline excess from a narrow fluorescein strip, fluorescein must be instilled at the outer canthus to avoid ocular surface alteration. For optimal results, viewing should occur between one and three minutes after the dye instillation allowing for spreading on the entire ocular surface and obtaining its maximal fluorescence intensity, particularly in ADDE.Citation71 We recommend using a Wratten #12 yellow filter combined with a blue light filter on the slit lamp to enhance contrast. Fluorescein sodium has an emission peak between 520–530nm, and it is absorbed and excited by light between 465–190nm.Citation79 The use of yellow filters, which transmit wavelengths above 495nm, better match the peak excitation of fluorescein dye, decreasing the overlap between excitation and emission spectra of fluorescein.Citation79 The NEI/Industry Workshop proposed classifying CFS by dividing the cornea into 5 zones and assigning 1–3 points to each zone according to the staining extent.Citation16 We suggest that instead of counting dots, which is difficult upon confluent staining and time-consuming, classify the staining pattern according to corneal quadrants, including the center involved. Thus, we propose the following severity ranges: mild = CFS of one quadrant without involving the central cornea, moderate = two quadrants involved and/or partial staining of the center, and severe = complete central staining of the cornea and/or >3 quadrants exhibiting epithelial damage ( and ).Citation16

Figure 5 Different patterns and intensities of positive corneal fluorescein staining in different subtypes of dry eye. (A) Paracentral epithelial punctate keratitis in ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. (B) Diffuse fluorescein staining in graft-vs-host-disease. (C) Severe punctate keratitis in Sjögren syndrome.

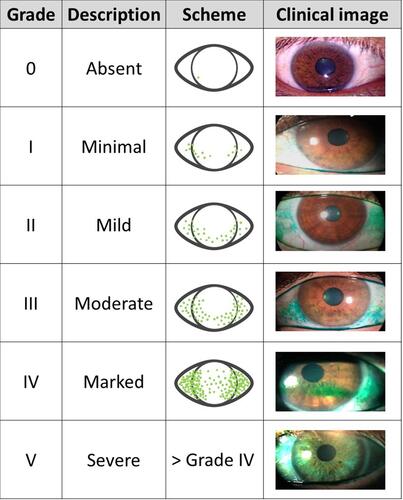

Oxford Scheme

The Oxford scheme uses a diagrammatic chart to estimate the ocular surface damage in DED. This diagnostic severity method uses an increasing scale of staining panels labeled A to E to obtain a dry eye grading score.Citation58 The staining grade observed in each panel, represented by punctate dots, increases by 0.5 of the logarithms of the number of dots between panels B to E. Staining ranges from 0 to 5 for each panel and 0 to 15 for the total exposed inter-palpebral area. The diagnosis, monitoring, and assessment of corneal and conjunctival staining is significantly improved by using this scheme ().Citation58

Figure 6 Representation of the Oxford scheme for ocular surface staining.

Lid Wiper Epitheliopathy

In the upper and lower eyelids, the “lid wiper” region, extending from the lateral canthus to the medial upper punctum horizontally, and from the subtarsal fold to the inner lid border superiorly, spreads tears over the ocular surface by acting as a wiping surface.Citation80 This elevated region of stratified epithelium is rich in conjunctival goblet cells. “Lid wiper” staining after instillation of lissamine green, rose bengal, or fluorescein dyes is known as lid wiper epitheliopathy (LWE).Citation4 It is commonly seen in contact lens wearers and DED patients.Citation80 Korb et al reported 88% of symptomatic DED patients had LWE, whereas it was present in only 16% of asymptomatic cases.Citation81 Although not proposed by the Panel as part of the severity classification, we believe LWE may aid the diagnosis of DED patients, mainly in those with symptomatic disease.

Schirmer Test

The Schirmer test remains one of the most widely used tools for measuring tear production. Currently, there are multiple variations to this technique, creating confusion and inconsistency among the scientific community.Citation82 The variant without anesthetic eyedrops measures the basal tear secretion and the reflex function of the main lacrimal gland, whose secretory activity is stimulated by irritation from the filter paper.Citation82 A variation on this procedure is the Schirmer I test performed with anesthesia, which only measures the basal lacrimal secretion function.Citation83 As a diagnostic tool, some authors describe the Schirmer I test with anesthesia to be more objective and reliable in reflecting the DED status.Citation83 A detailed description of the procedure is provided by Halberg and Berens.Citation84 Schirmer test type-I is recommended under topical anesthesia, placing the strips at the lateral third of the lower lid under low illumination.Citation83 This test is crucial for women with severe dry eye accompanied by dry mouth, joint pain, chronic fatigue, and a highly suspected or confirmed autoimmune condition.Citation85,Citation86 The Panel suggested a Schirmer-I test result of ≤5mm/5min is considered severe, ≤10mm/5min moderate, and ≥10mm/5min normal.Citation87

Conjunctival Hyperemia

A myriad of infectious and noninfectious etiologies are associated with conjunctival hyperemia. It results from a pathological and inflammatory response induced by cytokines, histamines, and neuropeptides, leading to vasodilation of the conjunctival microvasculature.Citation88 In DED, conjunctival hyperemia arises from the pro-inflammatory environment with resultant inflammation triggered by both ADDE and EDE.Citation89 Numerous subjective and objective conjunctival hyperemia grading systems are currently available.Citation88 Following our practical-based approach to DED, the Mexican Panel suggests grading conjunctival hyperemia based on Efron´s artist-rendered illustrations grading scale.Citation90,Citation91 We considered a (1) mild increase in conjunctival hyperemia with major vessels slightly engorged with or without limbal redness and/or ciliary flush as mild hyperemia; the (2) presence of limbal redness and ciliary flush in the setting of red conjunctiva as moderate hyperemia; and (3) severe hyperemia was defined as markedly red conjunctiva and limbal area with an intense ciliary flush.Citation90,Citation91 Since a descriptive analysis of slit lamp findings does not allow a clear cut between categories, we also suggest recording mild, moderate, and severe hyperemia as “1+”, “2+/3+”, and “>3+”, respectively ().

Eyelid Involvement

The lid margins must always be examined under a slit lamp to check for secretions along the anterior margin, such as crusts, scales, collarettes, sleeves, and cylindrical dandruff. Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are two obligate host-specific mites in the eyelid skin and lashes and the sebaceous and Meibomian glands, respectively.Citation92 The inflammatory process of blepharitis caused by Demodex mites remains elusive.Citation93 Diagnosis of Demodex can be obtained by hair follicle, skin biopsy, or IVCM. However, the presence of cylindrical dandruff is considered pathognomonic of Demodex infestation.Citation93 Then, the eyelids are compressed to assess the number (0 = all five glands; 1 = three to four glands; 2 = one to two glands; 3 = zero glands)Citation54 of Meibomian glands expressing meibum and the quality/thickness (0 = clear fluid; 1 = cloudy fluid; 2 = cloudy, granular particles; 3 = toothpaste consistency) of the secretions.Citation94 Transillumination meibography is a conventional method that complements manual expression, revealing meibum stagnation and Meibomian glands dropout.Citation95,Citation96 The TFBUT must be measured when diagnosing chronic blepharitis and MGD, which require additional therapeutic measures to help manage the condition and associated DED.Citation97,Citation98

Restoration of the Ocular Surface

The first definitions suggested DED resulted from either a tear deficiency (ADDE) or excessive evaporation (EDE).Citation16,Citation37 Increasing evidence of DED pathophysiology has led to the understanding that any ocular surface abnormality with resultant inflammation may destabilize tear dynamics.Citation30,Citation39 The concept of ocular surface restoration as part of a DED classification was first introduced by the SIDSO (See Above).Citation39 In their classification, the authors suggest DED severity is associated with the level of inflammation, which may be transient or self-sustained. The latter leads to chronic, and sometimes, irreversible damage of the ocular surface with persistent symptoms and signs.Citation30,Citation39

The Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel Proposed Treatment Approach Based on Dry Eye Disease Severity

The management of DED is complex due to its multifactorial nature. The well-accepted principle that diagnosis precedes therapy means that clinicians must endeavor to identify the degree to which different types of dry eye and other ocular surface conditions contribute to the patient’s clinical presentation. The primary objective of DED management is to restore homeostasis of the ocular surface by breaking the vicious cycle of the disease. While treatments may be indicated explicitly for one aspect of an individual patient’s condition, several treatment modalities might appropriately be recommended for multiple aspects of a DED clinical presentation. Beyond the aim of identifying and treating the leading cause of the disease, the management of DED typically involves dealing with chronic sequelae requiring continuous rather than short-term treatment to eliminate the dry eye issues.Citation99

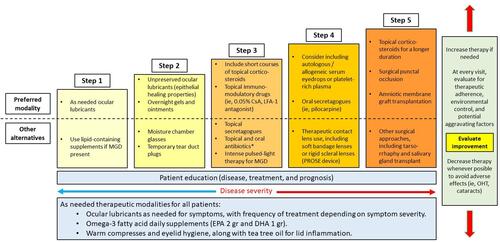

According to the disease stage, management algorithms are essential for a systematic therapy sequence, but such strategy is not always possible for DED as it is a complex condition varying inter-individually in severity and clinical course. However, to assist all eye care practitioners to custom a practical and efficacious evidence-based treatment strategy, we propose the management algorithm illustrated in and detailed in the following subsections. We also provide an evidence-based rationale for chosen therapeutic modalities.

Figure 7 Systematic treatment approach proposed by the Mexican Dry Eye Expert Panel.

General Rules for All Patients

According to DED severity, the recommended step-management for patients’ refractory to therapy is additive and sequential. Regardless of disease severity, specific recommendations are suitable for all patients, including as-needed ocular lubricants, with a frequency depending on symptom severity.

Patient Education

Once diagnosis and severity are established, patient education regarding treatment strategies and prognosis is paramount. It is crucial to determine the frequency of episodes, presenting symptoms and signs, systemic medication intake, and associated systemic conditions. Whenever possible, such medications should be suspended. It is essential to assess for therapeutic adherence at every visit and identify potential aggravating factors of DED.

Environmental Conditions

Low humidity, air conditioning, and other hostile environmental conditions can exacerbate DED symptoms and should be considered. For example, in patients with ADDE or EDE, including Sjögren syndrome, GvHD, rosacea or severe MGD, protective eyeglasses, prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem (PROSE), or low-water content contact lenses should be used to limit exposure to adverse environmental conditions.Citation100–Citation104

Electronic Devices

For patients with excessive use of electronic devices with digital screens such as computers, tablets, and smartphones, we recommend increasing the administration of topical lubricants and applying the 20/20/20 rule (every 20 minutes, look away from the screen and focus the gaze on something at 20 feet for 20 seconds) to relax the accommodation reflex and reduce eye strain.Citation105,Citation106

Management of Lid Inflammation

The Mexican Panel and others suggested that anterior blepharitis and MGD may occur at every severity stage in DED patients.Citation37,Citation107 As such, we recommend titrating the management of lid inflammation regardless of DED severity.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic alternatives of Demodex blepharitis reports resistance to usual lid hygiene with warm face cloths and topical antibiotics.Citation93 Nevertheless, it has a proven mechanical effect of mite removal in early-stage disease,Citation93 and a Cochrane meta-analysis suggests it provides symptomatic relief.Citation108 Due to its safety profile, tea tree oil is considered first-line therapy for symptomatic Demodex blepharitis.Citation93,Citation109 Thus, we recommend tea tree oil application once or twice a day along with performing lid hygiene with warm saline soaks to dissolve secretions and dilate Meibomian gland duct openings, followed by cleaning the lashes (remove Demodex mites) with a moistened cotton-tipped applicator.Citation93,Citation110 In cases of MGD, the use of omega-3 fatty acid daily supplements [eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 2 grams/day) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 1 gram/day)] may be used in all patients. Omega-3 fatty acids are associated with an anti-inflammatory effect improved TFBUT and Schirmer scores.Citation92

Step 1

Patients with mild disease are generally managed with conventional, low-risk, and commonly available therapies such as lubricant eye drops. Lubricant eye drops should have significant water retention capacity and sufficient precorneal residence time on the ocular surface, withstanding rheological forces and the flushing action of frequent blinking.Citation111–Citation114 For patients with MGD, lipid-containing supplements can be considered.Citation115

Step 2

For this therapy step, unpreserved ocular lubricants are recommended to minimize toxicity induced by the preservatives or by any inflammation in the damaged ocular surface. Lubricant eye drops with high viscosity and gel, or ointment formulations may also be considered. Preferentially overnight.Citation112,Citation116–Citation118 Eye drops promoting corneal and conjunctival epithelial healing and regeneration are also recommended for cases with significant ocular surface damage due to dryness.Citation114,Citation119,Citation120 The use of moisture chamber glasses is an alternative therapeutic modality to improve tear stability and reduce DED symptoms with as few as 10 minutes of use.Citation121 Temporary punctal occlusion has also been proven to improve symptoms, Schirmer test, and TFBUT scores.Citation122 However, the panel recommends punctal plugs must be used judiciously since inadvertent ocular surface inflammation may worsen due to inflammatory mediators’ retention.Citation36

Step 3

A short course of topical corticosteroids may be considered in patients with moderate to severe DED unresponsive to the abovementioned measurements. Topical corticosteroids improve DED symptoms and corneal and conjunctival staining.Citation123,Citation124 Avunduk et al reported a significant increase in positive goblet cells and human leukocyte antigen (HLA-DR)-II, assessed with impression cytology, as well as reduced symptom severity scores and corneal and conjunctival staining in patients treated with topical corticosteroids four times per day for 30 days.Citation124 Phosphate-formulated surface corticosteroids should be used whenever there is significant ocular surface inflammation and avoid prolonged administration (>30 days).Citation30,Citation123,Citation125

Also, the use of topical immunomodulatory therapy, including cyclosporine-A (CsA), a calcineurin inhibitor approved for ADDE management, and lifitegrast, a lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 antagonist (LFA-1), may be considered.Citation126,Citation127 0.05% or 0.1% CsA twice per day has shown to improve CFS and Schirmer values.Citation128,Citation129 Additionally, the 0.05% CsA formulation improved blurred vision, the need for adjunctive ocular lubricants, and the eye care specialist evaluation of global treatment response. On the other hand, anti-LFA-1 also shows significant improvement compared with placebo in the eye dryness score, and symptoms (ie, itching, foreign body sensation, and discomfort).Citation127 We recommend considering either 5.0% Lifitegrast or 0.05% CsA twice per day for at least 12 weeks.Citation127–Citation129 Topical corticosteroids, specifically 0.5% loteprednol etabonate BID, may be instilled 2–4 weeks prior to initiating CsA. The latter to reduce the associated stinging with CsA instillation.Citation130

Patients diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome should be prescribed topical and systemic immunomodulators plus corticosteroids to achieve the best therapeutic effect.Citation131,Citation132 Remember that topical immunomodulators (calcineurin and integrin inhibitors) need at least 3–6 months to take effect.Citation133–Citation136 In patients with concomitant chronic anterior blepharitis, topical macrolide formulations (azithromycin and erythromycin) should be used since these are not only bacteriostatic agents but also have a well-known anti-inflammatory effect.Citation137–Citation140

Step 4

In patients with severe DED, we recommend using 20% autologous serum (AS) four times per day for 2 to 4 weeks. Other authors have used this posology in randomized controlled trials of DED patients.Citation141,Citation142 AS provides numerous growth factors [ie, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, nerve growth factor (NGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 among others], inflammatory cytokine inhibitors, and bactericidal components.Citation143 The 20% dilution is recommended to avoid excessive antiproliferative effects. The latter since the concentration of TGF-β is five-fold higher in serum compared with tears.Citation144 AS main drawbacks include the burden of preparation, the need for refrigeration, and risk of infection with solution contamination.Citation126

Other alternatives for severe DED include platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and the use of therapeutic contact lenses. PRP is a blood product with a high platelet concentration that helps in corneal epithelial cell migration, differentiation, and proliferation and has proven safe and effective in DED.Citation145 The PROSE device is used to mimic the impaired ocular surface functions in diseases patients. Due to its principle of no corneal contact, it provides high oxygen permeability and protection against the lid shearing blinking forces, creating an adequate environment that enhances healing of the corneal surface.Citation146

Step 5

For patients with severe, refractory DED, we recommend the use of topical corticosteroids for a longer duration, and coadjutant surgery is also recommended in cases unable to restore the ocular surface with medical treatment alone, including amniotic membrane graft, lateral tarsorrhaphy, and eyelid malposition correction to avoid complications leading to irreversible vision impairment.Citation118 Particular details from each technique are beyond the scope of this report.

Recommended Follow-Up Guidelines

Careful follow-up must ensure patients comply with the recommended management option(s) and establish improvement symptoms and/or signs. The appropriate time to assess the therapeutic success depends on the individual response and the therapy in question.Citation99 A literature review suggests waiting for 1–3 months on therapy except for cyclosporine, which takes effect after more than 3 months, and study periods are typically longer than 3 months. Therefore, for most treatments, changes before this period would appear premature.Citation128,Citation133,Citation147 Patients with mild symptomatic dry eye may be seen once every six weeks or longer. If the symptoms are severe enough, patients must be seen more frequently (every 2–3 weeks) to monitor disease progression closely. Corneal fluorescein staining, the Oxford grading scheme, and TFBUT should continuously be assessed during follow-up visits since these methods are highly sensitive diagnostic tests and accurate indicators of treatment response.Citation58,Citation148–Citation150

If the patient presents with systemic and ocular symptoms and signs suggestive of an autoimmune disease such as Sjögren’s syndrome or has ADDE with a significantly low Schirmer’s test (<5mm) in at least one eye, like in GvHD, they should be referred to a specialist for evaluation and treatment. The same referral applies for patients with severe DED due to cicatrizing conjunctivitis (ie, erythema multiforme, ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid, lichen planus) and other complex cases.Citation151

Discussion

To date, there is no global consensus agreement on how to diagnose DED. Neither there is a pathognomonic sign or symptom nor a “gold-standard” test with exact cut-off values allowing distinction between healthy and dry eyes.Citation152 The latter results from discordance between symptoms and signs, poorly standardized criteria, and methodology for evaluating DED,Citation152 cross-cultural differences between populations,Citation153,Citation154 and environmental factors that may influence disease severity.Citation30,Citation155 Thus, many factors preclude adequate DED diagnosis and severity grading evaluation. Based on the strengths and weaknesses of previous classification efforts from recognized expert groups, The Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel proposes a simple, practical, and inexpensive algorithm that allows classifying DED according to its severity.

Many different DED expert panels have significantly contributed to our current understanding and treatment of this complex condition. The Triple Classification System (2005) graded DED severity based on increasing symptoms and signs; however, the authors proposed that mild disease is absent of objective slit-lamp findings.Citation107,Citation156 The Tear Dysfunctional Study Group (2006) excluded lid margin disease from their DED severity criteria.Citation36 And, although ADDE and EDE´s pathogenic mechanisms are different,Citation157 overlaps in symptoms,Citation158 and most frequently coexist in a mixed form of dry eye.Citation31,Citation37 Interestingly, this Panel proposed “tear dysfunctional syndrome” as a better name for dry eye disease.Citation36 Such a name seems more accurate from a pathophysiological standpoint; however, the previous concept of “dry eye” was ingrained within the literature and thus maintained.Citation37 The DEWS Subcommittee (2007) modified the basic scheme previously proposed by the Tear Dysfunctional Study Group by including lid margin disease and the frequency of DED symptoms.Citation37 They proposed using nine criteria to classify DED severity in four levels. Although the Subcommittee suggested severe DED must have signs and symptoms, there was no clear indication on which criteria were ought to be used to classify mild to moderate disease.Citation37 All these systems suggest severe symptoms and signs are required to diagnose severe DED.

Few DED symptoms in the presence of clear signs indicate the possibility of reduced corneal sensitivity (neurotrophic keratopathy), requiring esthesiometry confirmation and adequate treatment to avoid ongoing and irreversible damage to the ocular surface.Citation159–Citation161 The OECG (2014) was the first to recognize the possibility of severe DED in the presence of severe symptoms without significant signs and vice versa.Citation38 The Panel suggested the combination of an OSDI ≥33 and CFS/Oxford Scale ≥3 enough for establishing severe DED. In cases of symptoms and signs discordance, the authors proposed three different scenarios in which, using 14 additional criteria, a diagnosis of severe DED may be established.Citation38 However, the OECG recognizes that five of the additional proposed criteria (impression cytology, IVCM, hyperosmolarity, aberrometry, and inflammatory markers) are not universally available, are costly, and require trained personnel.Citation38 Like the OECG, we agree with the possibility of severe DED without significant symptoms.Citation38

However, although widely used, the OSDI might not represent the most reliable option to determine DED severity. Our reasons are twofold. First, a study applying Rasch analysis found that the five-category response structure of the OSDI resulted in inadequate response thresholds.Citation162 The authors found ordered thresholds and improved intervals in each category after collapsing the “half of the time” and “most of the time” responses into one category.Citation162 Second, the process of validating a questionnaire to another language often encounters serious cultural translation-adaption problems, even when performed by professionals, that may adversely influence results.Citation163 Van Zyl et al reports significant differences between individuals and entire cultures in expressing emotions within the same language and across languages.Citation153 Thus, the Mexican Panel suggests symptom frequency may be best considered the primary criteria for classifying DED. Instead, we propose using a validated questionnaire (DEQ-5) as a contributory rather than a primary criterion.

The SIDSO (Italy, 2021) used the nominal group technique and the Delphi approach to classify DED severity.Citation39 They subdivided DED into three types based on (1) the inflammatory component of DED (subclinical, clinically reversible, and clinically irreversible), (2) the symptoms pattern and frequency, and (3) the ocular surface capability to leave the DED vicious cycle, re-equilibrating.Citation39 However, the SIDSO does not provide clinical tests to evaluate the ocular surface.Citation39

Apart from symptom frequency (detailed above), we also included ocular surface restoration in our classification scheme. The restoration capacity of the cornea and conjunctiva epithelia, as a function of therapeutic efficacy, is a sensitive way to measure disease severity. It is the only criterion that must be present in each severity level. The Mexican Panel also suggests reintroducing the CFS system proposed by the NEI/Industry Workshop, which divides the cornea into five areas and assigns 1–3 points to each affected area based on the amount and distribution of staining.Citation16 However, we propose a modification to the latter. We suggest counting the entire area as affected rather than staining dots as stated before. Also, we emphasize central CFS. We considered partial and complete staining of the central cornea as moderate and severe CFS, respectively. The central zone was deemed as most important by the Mexican Panel as it is the most visually significant.Citation164 Kaido et al reported that the severity of epithelial staining at the center of the cornea was significantly associated with optical disturbances affecting visual performance, including visual maintenance ratio, varying visual acuity, and comalike and total high order aberrations.Citation165

The proposed model has several limitations. Under its nature, panel-based consensus development is not evidence-based. The lack of a universal definition of DED, a pathognomonic sign or symptom, a gold-standard diagnostic and therapeutic tool makes it challenging to classify DED patients objectively according to severity. While the DEWS Subcommittee suggests severe DED must have signs and symptoms,Citation37 the OECGCitation38 and the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert does not.

Conclusions

Dry eye disease is an increasingly prevalent, multifactorial, and highly complex health problem that may require multidisciplinary management for the ocular surface alterations and their neurological, metabolic, and immunological aspects. Successful management of the disease relies on early diagnosis, correct classification of subtype and severity of DED, followed by a customized treatment strategy which focuses on resolving the problems experienced by the individual patient, together with in-depth and effective follow-up to minimize the problem, thus improving the patient’s quality of life. Next step, we intend to validate the proposed DED severity classification of the Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel in the setting of controlled studies.

It is important to remember that the term “dry eye” describes a multifactorial condition, the hallmarks of which are signs on the ocular surface with clinical manifestations and etiologies that vary inter-individually. Therefore, the patient’s dry eye severity classification evaluation should be comprehensive, practical, and accessible to any eye care clinician. In this way, a systematic and individualized treatment approach accounting for each affected individual’s specific circumstances will assure improvement of her (his) therapeutic outcome.

Abbreviations

ADDE, aqueous tear deficiency; ADES, Asia Dry Eye Society; AS, autologous serum; AECG, American-European Consensus Group; BID, twice a day; CFS, corneal fluorescein staining; CsA, cyclosporine-A; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DED, dry eye disease; DEQ-5, Dry Eye Disease Questionnaire-5; EDE, evaporative tear deficiency; GvHD, graft-versus-host disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IVCM, in vivo confocal microscopy; JDES, Japan Dry Eye Society; LFA-1, lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1; LWE, lid wiper epitheliopathy; MGD, Meibomian gland dysfunction; NEI, National Eye Institute; NGF, nerve growth factor; OECG, ODISSEY European Consensus Group; OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index; PROSE, prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem; PRP, platelet-rich plasma; QoL, quality of life; SICCA, Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance; SIDSO, Società Italiana di Dacriologia e Superficie Oculare; TFBUT, tear film breakup time; TFOS DEWS, Tear Film & Ocular Surface Dry Eye Workshop; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The Mexican Dry Eye Disease Expert Panel members want to thank Laboratorios Théa México for their unlimited support during workshop meetings and for facilitating the preparation of the report for publication.

They also would like to thank Drs. Raul E. Ruiz-Lozano for the design and elaboration of figures and tables and Dr. Alejandro Rodríguez-García for providing the clinical images for the report. Finally, the authors would like to thank Lapharcon, LLC for their logistical support in performing the consensus meetings.

Disclosure

Dr Everardo Hernandez-Quintela reports personal fees from Thea Laboratories, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276–283. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008

- Al-Mohtaseb Z, Schachter S, Shen Lee B, Garlich J, Trattler W. The relationship between dry eye disease and digital screen use. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:3811–3820. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S321591

- Rodriguez-Garcia A, Loya-Garcia D, Hernandez-Quintela E, Navas A. Risk factors for ocular surface damage in Mexican patients with dry eye disease: a population-based study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:53–62. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S190803

- Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539–574. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001

- Berg EJ, Ying GS, Maguire MG, et al. Climatic and environmental correlates of dry eye disease severity: a report from the dry eye assessment and management (DREAM) Study. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(5):25. doi:10.1167/tvst.9.5.25

- Sanchez-Valerio MDR, Mohamed-Noriega K, Zamora-Ginez I, Baez Duarte BG, Vallejo-Ruiz V. Dry eye disease association with computer exposure time among subjects with computer vision syndrome. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4311–4317. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S252889

- Osae EA, Ablordeppey RK, Horstmann J, Kumah DB, Steven P. Clinical dry eye and meibomian gland features among dry eye patients in rural and urban Ghana. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4055–4063. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S275584

- Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IO, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90–98. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.033

- Ward MF 2nd, Le P, Donaldson JC, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the association between diabetes mellitus and dry eye disease. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2019;26(5):295–300. doi:10.1080/09286586.2019.1607882

- Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334–365. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003

- Papas EB. The global prevalence of dry eye disease: a Bayesian view. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2021;41(6):1254–1266. doi:10.1111/opo.12888

- Graue-Hernandez EO, Serna-Ojeda JC, Estrada-Reyes C, Navas A, Arrieta-Camacho J, Jimenez-Corona A. Dry eye symptoms and associated risk factors among adults aged 50 or more years in Central Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2018;60(5):520–527. doi:10.21149/9024

- Martinez JD, Galor A, Ramos-Betancourt N, et al. Frequency and risk factors associated with dry eye in patients attending a tertiary care ophthalmology center in Mexico City. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1335–1342. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S106451

- McDonald M, Patel DA, Keith MS, Snedecor SJ. Economic and humanistic burden of dry eye disease in Europe, North America, and Asia: a systematic literature review. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(2):144–167. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2015.11.002

- Yu K, Bunya V, Maguire M, et al. Systemic conditions associated with severity of dry eye signs and symptoms in the dry eye assessment and management study. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(10):1384–1392. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.03.030

- Lemp MA. Report of the national eye institute/industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J. 1995;21(4):221–232.

- Potvin R, Makari S, Rapuano CJ. Tear film osmolarity and dry eye disease: a review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2039–2047. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S95242

- Ng A, Keech A, Jones L. Tear osmolarity changes after use of hydroxypropyl-guar-based lubricating eye drops. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;12:695–700. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S150587

- Bartlett JD, Keith MS, Sudharshan L, Snedecor SJ. Associations between signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: a systematic review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1719–1730. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S89700

- Rolando M, Zierhut M, Barabino S. Should we reconsider the classification of patients with dry eye disease? Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(3):521–523. doi:10.1080/09273948.2019.1682618

- Shimazaki J. Definition and diagnostic criteria of dry eye disease: historical overview and future directions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(14):DES7–DES12. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-23475

- Galor A, Zlotcavitch L, Walter SD, et al. Dry eye symptom severity and persistence are associated with symptoms of neuropathic pain. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(5):665–668. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306057

- Baudouin C, Aragona P, Messmer EM, et al. Role of hyperosmolarity in the pathogenesis and management of dry eye disease: proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul Surf. 2013;11(4):246–258. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2013.07.003

- Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):438–510. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011

- Lemp MA, Bron AJ, Baudouin C, et al. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(5):792–798. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.032

- Versura P, Profazio V, Campos EC. Performance of tear osmolarity compared to previous diagnostic tests for dry eye diseases. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35(7):553–564. doi:10.3109/02713683.2010.484557

- Jacobi C, Jacobi A, Kruse FE, Cursiefen C. Tear film osmolarity measurements in dry eye disease using electrical impedance technology. Cornea. 2011;30(12):1289–1292. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821de383

- Stern ME, Pflugfelder SC. Inflammation in dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2004;2(2):124–130. doi:10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70148-9

- Mochizuki H, Fukui M, Hatou S, Yamada M, Tsubota K. Evaluation of ocular surface glycocalyx using lectin-conjugated fluorescein. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:925–930. doi:10.2147/opth.s12648

- Baudouin C, Irkec M, Messmer EM, et al. Clinical impact of inflammation in dry eye disease: proceedings of the ODISSEY group meeting. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96(2):111–119. doi:10.1111/aos.13436

- Geerling G, Baudouin C, Aragona P, et al. Emerging strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction: proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(2):179–192. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.01.006

- Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1264–1268. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.9.1264

- Wong J, Lan W, Ong LM, Tong L. Non-hormonal systemic medications and dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2011;9(4):212–226. doi:10.1016/S1542-0124(11)70034-9

- Gupta N, Prasad I, Himashree G, D’Souza P. Prevalence of dry eye at high altitude: a case controlled comparative study. High Alt Med Biol. 2008;9(4):327–334. doi:10.1089/ham.2007.1055

- Murube J, Nemeth J, Hoh H, et al. The triple classification of dry eye for practical clinical use. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(6):660–667. doi:10.1177/112067210501500602

- Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: a Delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea. 2006;25(8):900–907. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000214802.40313.fa

- Lemp MA, Foulks GN. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75–92. doi:10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2

- Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G, et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(9):1168–1176. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304619

- Barabino S, Aragona P, Di Zazzo A, Rolando M. with the contribution of selected ocular surface experts from the Societa Italiana di Dacriologia e Superficie O. Updated definition and classification of dry eye disease: renewed proposals using the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(1):42–48. doi:10.1177/1120672120960586

- Tsubota K, Yokoi N, Watanabe H, et al. A new perspective on dry eye classification: proposal by the Asia dry eye society. Eye Contact Lens. 2020;46(1):S2–S13. doi:10.1097/ICL.0000000000000643

- Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405–412. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S5555

- Shimazaki J, Ohashi Y, Kinoshita S, Sawa M, Takamura E. Definition and criteria of dry eye. Ganka. 1995;37(7):765–770.

- Shimazaki S. Definition and diagnosis of dry eye 2006. J Eye. 2006;24:181–184.

- Tsubota K, Yokoi N, Shimazaki J, et al. New perspectives on dry eye definition and diagnosis: a consensus report by the Asia dry eye society. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(1):65–76. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2016.09.003

- Hwang HS, Kim EC, Kim MS. Novel tear interferometer made of paper for lipid layer evaluation. Cornea. 2014;33(8):826–831. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000161

- Craig JP, Nelson JD, Azar DT, et al. TFOS DEWS II report executive summary. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(4):802–812. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.08.003

- Gonzalez Block MA, Reyes Morales H, Hurtado LC, Balandran A, Mendez E. Mexico: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2020;22(2):1–222.

- Resnikoff S, Lansingh VC, Washburn L, et al. Estimated number of ophthalmologists worldwide (International Council of Ophthalmology update): will we meet the needs? Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(4):588–592. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314336

- Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(11):2149–2157. doi:10.1185/030079906X132640

- Dietrich-Ntoukas T, Cursiefen C, Westekemper H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease: report from the German-Austrian-Swiss Consensus Conference on Clinical Practice in chronic GVHD. Cornea. 2012;31(3):299–310. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318226bf97

- Deng SX, Kruse F, Gomes JAP, et al. Global consensus on the management of limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 2020;39(10):1291–1302. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002358

- Rege A, Kulkarni V, Puthran N, Khandgave T, Clinical A. Study of subtype-based prevalence of dry eye. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(10):2207–2210. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/6089.3472

- Alves M, Reinach PS, Paula JS, et al. Comparison of diagnostic tests in distinct well-defined conditions related to dry eye disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97921. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097921

- Pflugfelder SC, Tseng SC, Sanabria O, et al. Evaluation of subjective assessments and objective diagnostic tests for diagnosing tear-film disorders known to cause ocular irritation. Cornea. 1998;17(1):38–56. doi:10.1097/00003226-199801000-00007

- Barabino S, Labetoulle M, Rolando M, Messmer EM. Understanding symptoms and quality of life in patients with dry eye syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(3):365–376. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2016.04.005

- Pflugfelder SC, Baudouin C. Challenges in the clinical measurement of ocular surface disease in glaucoma patients. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1575–1583. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S24410

- Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33(2):55–60. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010

- Bron AJ, Evans VE, Smith JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22(7):640–650. doi:10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008

- Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):9–16. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210571

- Martinez JD, Galor A, Amescua G, et al. Transcultural validation of the 5-item dry eye questionnaire for the Mexican population. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(10):2313–2324. doi:10.1007/s10792-018-01068-3

- Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, et al. Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:111. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-111

- Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(5):615–621. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.5.615

- Beltran F, Betancourt NR, Martinez J, et al. Transcultural validation of ocular surface disease index (osdi) questionnaire for Mexican population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(15):6050.

- Schaumberg DA, Gulati A, Mathers WD, et al. Development and validation of a short global dry eye symptom index. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(1):50–57. doi:10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70053-8

- McMonnies CW, Ho A. Responses to a dry eye questionnaire from a normal population. J Am Optom Assoc. 1987;58(7):588–591.

- Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Moody K, Hickson-Curran SB. Contact Lens Dry Eye Questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) and opinion of contact lens performance. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89(10):1435–1442. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e318269c90d

- Garza-Leon M, Amparo F, Ortiz G, et al. Translation and validation of the contact lens dry eye questionnaire-8 (CLDEQ-8) to the Spanish language. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2019;42(2):155–158. doi:10.1016/j.clae.2018.10.015

- Tsubota K. Short tear film breakup time-type dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(14):DES64–DES70. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-23746

- Shimazaki-den S, Dogru M, Higa K, Shimazaki J. Symptoms, visual function, and mucin expression of eyes with tear film instability. Cornea. 2013;32(9):1211–1218. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318295a2a5

- Kaido M, Ishida R, Dogru M, Tsubota K. Visual function changes after punctal occlusion with the treatment of short BUT type of dry eye. Cornea. 2012;31(9):1009–1013.

- Whitcher JP, Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, et al. A simplified quantitative method for assessing keratoconjunctivitis sicca from the Sjogren’s Syndrome International Registry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):405–415. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.09.013

- Akpek EK, Amescua G, Farid M, et al. Dry eye syndrome preferred practice pattern(R). Ophthalmology. 2019;126(1):P286–P334. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.10.023

- Johnson ME, Murphy PJ. The Effect of instilled fluorescein solution volume on the values and repeatability of TBUT measurements. Cornea. 2005;24(7):811–817. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000154378.67495.40

- Nichols KK, Foulks GN, Bron AJ, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: executive summary. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1922–1929. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-6997a

- Abelson R, Lane KJ, Rodriguez J, et al. Validation and verification of the OPI 2.0 System. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:613–622. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S29431

- Patel S, Murray D, McKenzie A, Shearer DS, McGrath BD. Effects of fluorescein on tear breakup time and on tear thinning time. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1985;62(3):188–190. doi:10.1097/00006324-198503000-00006

- Vitali C, Moutsopoulos HM, Bombardieri S. The European Community Study Group on diagnostic criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome. Sensitivity and specificity of tests for ocular and oral involvement in Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53(10):637–647. doi:10.1136/ard.53.10.637

- Begley C, Caffery B, Chalmers R, Situ P, Simpson T, Nelson JD. Review and analysis of grading scales for ocular surface staining. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(2):208–220. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2019.01.004

- Eom Y, Lee JS, Keun Lee H, Myung Kim H, Suk Song J. Comparison of conjunctival staining between lissamine green and yellow filtered fluorescein sodium. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015;50(4):273–277. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2015.05.007

- Efron N, Brennan NA, Morgan PB, Wilson T. Lid wiper epitheliopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;53:140–174. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.04.004

- Korb DR, Herman JP, Blackie CA, et al. Prevalence of lid wiper epitheliopathy in subjects with dry eye signs and symptoms. Cornea. 2010;29(4):377–383. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ba0cb2

- Zeev MS-B, Miller DD, Latkany R. Diagnosis of dry eye disease and emerging technologies. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:581–590. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S45444

- Li N, Deng X-G, He M-F. Comparison of the Schirmer I test with and without topical anesthesia for diagnosing dry eye. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(4):478–481.

- Halberg GP, Berens C. Standardized Schirmer tear test kit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1961;51(5):840–842. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(61)91827-X

- Danjo Y. Diagnostic usefulness and cutoff value of Schirmer’s I test in the Japanese diagnostic criteria of dry eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235(12):761–766. doi:10.1007/BF02332860

- Villarreal-Gonzalez AJ, Jocelyn Rivera-Alvarado I, Rodriguez-Gutierrez LA, Rodriguez-Garcia A. Analysis of ocular surface damage and visual impact in patients with primary and secondary Sjogren syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(8):1249–1257. doi:10.1007/s00296-020-04568-7

- Senchyna M, Wax MB. Quantitative assessment of tear production: a review of methods and utility in dry eye drug discovery. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2008;1(1):1–6. doi:10.1007/s12177-008-9006-2