Abstract

Background

The purpose of this paper is to describe clinical characteristics and determine correlations between clinical outcomes and antifungal susceptibility among molecularly characterized ocular Fusarium isolates in Brazil.

Methods

Forty-one Fusarium isolates obtained from 41 eyes of 41 patients were retrieved from the ophthalmic microbiology laboratory at São Paulo Federal University and grown in pure culture. These isolates were genotyped and antifungal susceptibilities determined for each isolate using a broth microdilution method. The corresponding medical records were reviewed to determine clinical outcomes.

Results

The 41 isolates were genotypically classified as Fusarium solani species complex (36 isolates, 88%), Fusarium oxysporum species complex (two isolates, 5%), Fusarium dimerum species complex (one isolate, 2%) and two isolates that did not group into any of the species complexes. Final best corrected visual acuity varied from 20/20 to light perception and was on average 20/800 (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR) 1.6). A history of trauma was the most common risk factor, being present in 21 patients (51%). Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was necessary in 22 patients (54%). Amphotericin B had the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration for 90% of isolates (MIC90) value (2 μg/mL) and voriconazole had the highest (16 μg/mL). There was an association between a higher natamycin MIC and need for therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty (Mann–Whitney test, P < 0.005).

Conclusion

Trauma was the main risk factor, and therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was necessary in 54% of patients. Amphotericin B had the lowest MIC90 (2 μg/mL) of the three antifungal agents tested. There was an association between higher natamycin MIC levels and corneal perforation, emphasizing the need for antifungal susceptibility testing and tailoring of antifungal strategies.

Introduction

Brazil, like other countries having an important territorial part in the tropical zone, has a significant number of fungal keratitis cases, ranging from 11% to 56% of all positive cultures.Citation1,Citation2 In countries like India and People’s Republic of China, fungi can be the etiology in up to 36% and 62%, respectively, of all keratitis cases.Citation3,Citation4 Among the fungi causing keratitis, Fusarium species is the most prevalent. Studies show that 45%–67% of fungal keratitis in Brazil is caused by this microorganism.Citation1,Citation2,Citation5–Citation7 Among the Fusarium species that are pathogenic to the eye, Fusarium solani is the most common (found in up to 91% of isolates),Citation7 followed by Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium dimerum.Citation8,Citation9

Treatment of keratomycosis is still largely empirical, without a consensus on the role of susceptibility testing in choosing the most appropriate therapy. Ocular microbiology laboratories do not routinely perform antifungal susceptibility testing because it is time-consuming, laborious, and challenging, especially for molds. However, in vitro resistance of Fusarium isolates against many of the available antifungal agents has been demonstrated to be common, mainly for F. solani. Studies have already shown that there is a correlation between antibiotic susceptibilities and clinical outcomes in bacterial keratitis.Citation10–Citation12 Some studies are starting to show that a relationship between antifungal susceptibility and clinical outcomes might also exist in cases of fungal keratitis.Citation13–Citation15 Methods for testing antifungal susceptibility have improved significantly. Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for Fusarium species has been demonstrated to be clinically relevant and provides valuable information for choosing the best topical antifungal therapy.

There is a lack of epidemiologic and clinical information on fungal ulcers in Brazil. Also, information on antifungal susceptibilities and correlation with clinical outcomes is limited, and such information will be very useful to improve treatment strategies for Fusarium species, which is the main pathogen in cases of fungal keratitis in Brazil and many other countries. In the present study, 41 isolates from 41 patients presenting with Fusarium keratitis were identified by genotyping, tested for their antifungal susceptibility to natamycin, amphotericin B, and voriconazole, and correlated with clinical outcomes.

Methods and materials

Isolates

Forty-one Fusarium isolates, representing 41 patients, were retrospectively selected from the ocular microbiology laboratory at the Federal University of São Paulo, based on the availability of medical records. We included isolates from 1997 to 2010. The source of all isolates was corneal scrapings from patients with keratitis. The reference strains Candida albicans American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 90028, Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019, and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were included as quality controls for the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute antifungal testing method. Morphologic species-specific identification of all strains was performed in the mycology laboratory at the Federal University of São Paulo.

Medical records review

Following institutional ethics committee approval (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa da Universidade Federal de São Paulo, registration number 1066/08), the medical records from the 41 affected patients were made available for review. All patients included in the chart review had positive corneal culture results for Fusarium species.

The follow-up best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of patients treated with topical or oral antimicrobial agents was the visual acuity measured when the patient was considered cured (inactive corneal scar with intact epithelium). No patient had additional pathology at baseline to account for decreased visual acuity at any time during management.

The final BCVA of patients who underwent therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was the last BCVA measured prior to surgery. For this group of patients, the time to cure was assigned as an estimate, which was the longest time to cure among clinically treated patients.

Snellen visual acuities were converted to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (LogMAR) for the purpose of data analysis. Vision levels, classified as count fingers, hand motion, and light perception, were assigned Snellen acuities of 1/200, 0.5/200 and 20/20,000. The corresponding LogMAR visual acuities were 2.3, 2.6, and 3.0, respectively, similar to a previously published scale.Citation16

Antifungal susceptibility tests

The methodology as described in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document M38-A2Citation17 was followed for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Additive drug dilutions were prepared to yield twice the final strength required for the test. Stock solutions of amphotericin B, voriconazole, and natamycin at their final concentrations were frozen at −80°C until needed. The agents evaluated in this study have well established microdilution MIC ranges for the quality control strains used.

Isolates and DNA extraction

Forty-one Fusarium isolates, collected from 41 patients seen in the department of ophthalmology at the Federal University of São Paulo were retrospectively selected from the ocular and molecular microbiology laboratory culture collection, based on availability of medical records. All isolates were recovered from corneal scraping cultures from patients with clinically diagnosed infectious keratitis. Frozen isolates on skim milk were cultured twice on Sabouraud agar. Total fungal DNA was extracted from fresh cultured isolates after boiling for 15 minutes using the PrepMan ultra sample preparation reagent (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA, USA).

Amplification and sequencing of internal transcribed spacer region

The internal transcribed spacer region, comprising ITS1, ITS2, and 5.8S rRNA, was amplified in a 25 μL polymerase chain reaction mixture containing 10 μL GoTaq Green polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Master Mix (3.0 mM MgCl, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate [dNTP], buffer, and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 0.4 μM of each of the following primers, F18S (5′-GCGGAG-GGATCATTACCGAGTT-3′) and F28S (5′-CAGCGGGT-ATTCCTACCTGATC-3′), 1 μL DNA template, and diethyl dicarbonate water. Amplification was performed using the Master Cycler gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with the following conditions: one cycle at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 45 cycles with a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 seconds, an annealing step at 55°C for 30 seconds, and an extension step at 68°C for 2 minutes. The amplification was carried out in the presence of negative and positive controls. Amplified products separated on 1% agarose gel were purified using a QIAquick purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Polymerase chain reaction products were sequenced on both strands using Big Dye Terminator chemistry on the 3000 ABI genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences obtained were edited using SeqMan (DNAStar, Madison, WI, USA) and searched for similarity in GenBank using the BLAST algorithm program with automatically adjusted parameters.

Phylogenetic analysis

Before alignment, sequences were scanned for quality using the Phred base-calling program. The upstream and downstream regions just after the primer annealing regions were manually trimmed (SeqMan, DNAStar). Thirty-nine edited sequences ranging from 502 to 566 base pairs exported as a FASTA file were aligned using the Muscle multiple sequence alignment algorithm implemented by the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis program version 5.1.Citation18 Assignment of haplotypes was done using DnaSP version 5. For the purposes of comparison in the phylogenetic tree, sequences of the internal transcribed spacer region representing a recent Fusarium species complex classification system were included.Citation8 The internal transcribed spacer sequence from Lecanicillium lecanii was used as an outgroup (DQ007051). Selection of the substitution model that best fits the data as well as estimation of model parameters such as base pair frequencies, substitution rates, transition and transversion ratio, proportion of invariant sites, and gamma shape parameter, were computed using jModel test.Citation19 A Bayesian phylogenetic tree implementing the general time reversible model with a proportion of invariable sites and gamma-distributed rate variation across sites was constructed using MrBayes version 3.1.2.Citation20 Posterior probabilities of the tree were estimated by running two simultaneous and independent Metropolis-coupled Monte Carlo Markov chains with three heated and one cold chain for 5 million generations. Chains were sampled every 100th cycle. The consensus tree was summarized after discarding the first 25% generations as burn-in. The tree was visualized and edited using Mesquite version 2.75.Citation21

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The ITS nucleotide sequences reported in this work have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JX270136, JX270138 to JX270143, JX270148 to JX270153, JX270157 to JX270173, and JX270175 to JX270183.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using Stata software version 11.0 (College Station, TX, USA). Tests of significance were two-tailed with P ≤ 0.05. Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze data that did not follow a normal distribution (ie, antifungal MICs).

Results

Identification

Morphologic identification of the organism as belonging to the Fusarium genus took a mean of 5.8 (2–14) days. Identification to the species level after genus classification took 4 further days on average. Morphology-based identification classified the 41 isolates as F. solani (n = 35), F. oxysporum (n = 4), and F. dimerum (n = 2).

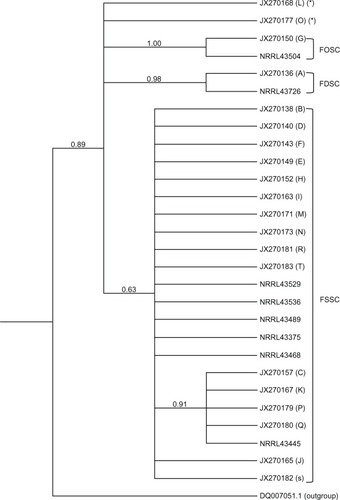

Based on genotype, the 41 isolates were classified into three groups, ie, F. solani species complex (FSSC, 36 isolates, 88%), F. oxysporum species complex (FOSC, two isolates, 5%), and F. dimerum species complex (FDSC, one isolate, 2%), with two isolates not grouping in any species complex. The relationship between the genotyped isolates is shown in the consensus tree (). In the major species complex found, ie, FSSC, 16 distinct haplotypes were identified. Haplotype D was the most frequent among the FSSC (13 of 34 sequences, 38.2%). The posterior probability supporting the whole FSSC clade was 63%. An internal subcluster including haplotypes c, k, p, and q clustered together with a posterior probability support of 91%. The FDSC and FOSC groups, each represented by a single haplotype, were supported by a posterior probability of 98% and 100%, respectively.

Figure 1 Consensus Bayesian phylogenetic tree of the ITS 1 and ITS 2 regions summarized after discarding as burn-in the first 25% generations of the Metropolis-coupled Monte Carlo Markov chain analysis. Numbers in the branches indicate the posterior probabilities estimate. Letter in parentheses corresponds to the haplotype. Only one sequence of each haplotype is represented in the tree. The parenthesis marked (*) represents isolates that did not group into any species complex.

Clinical characteristics and epidemiology

The 41 samples were isolated from 41 eyes of 41 patients. The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in and . The mean follow-up time in this study was 9.3 (1–24) months. Mean time to diagnosis, defined as the interval from symptom onset until a specific diagnosis was made, was 19 ± 12 (3–90) days. Risk factors for infectious keratitis were found in 26 patients. A history of trauma was the most frequent risk factor, being present in 21 patients (51%).

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of keratitis cases

Table 2 Further clinical characteristics of keratitis cases

Management

Complete information on the treatment protocol was present in the records of 37 patients. Patients who had a positive culture and/or microscopy for a mold were started on a topical antifungal, ie, natamycin 5% or amphotericin B 0.15% hourly. A systemic antifungal (ketoconazole 200 mg or fluconazole 200 mg twice daily) was added for ulcers larger than 6 mm in diameter or if no improvement with topical antifungal use was seen after 5 days.

Topical amphotericin B 0.15% (compounded from Fungizone®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) was used in 24 cases, as monotherapy in seven cases, and in combination with other antimicrobial agents in 15 cases. Topical natamycin 5% (Pimaricina®, Ophthalmos, São Paulo, Brazil) was used in 14 cases and as monotherapy in one case. Oral fluconazole 150 mg (generic fluconazole, Medley Pharmaceuticals, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) or ketoconazole 200 mg (generic ketoconazole, Medley Pharmaceuticals) twice daily was used in 29 cases.

Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was necessary in 22 patients (54%), the indication being perforation in 19 cases and severe infiltrates nonresponsive to clinical therapy in three cases. Seven of the therapeutic grafts failed (four due to reinfection, two because of rejection, and one as a result of stromal melting) and repeat penetrating keratoplasty was successful in only one case, which had failed initially because of rejection.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

Antifungal susceptibilities were tested for 38 isolates. Minimum inhibitory concentrations for 90% of the isolates (MIC90), medians, and MIC ranges for the Fusarium isolates are listed in . Amphotericin B had the lowest MIC values and voriconazole had the highest. Most of the isolates were equally susceptible to natamycin and amphotericin B. There was a strong association between a higher natamycin MIC and need for penetrating keratoplasty ().

Table 3 MIC90 values for voriconazole, natamycin, and amphotericin B (μg/mL)

Table 4 Association between mean (SD) MIC values for antifungal agents and need for PK

Discussion

Fungal keratitis is a very prevalent disease in developing countries, and tends to have a poorer outcome when compared with keratitis caused by other pathogenic organisms. Fusarium is the leading pathogen in fungal keratitis in most of the studies worldwide, particularly in tropical regions.Citation3–Citation7 Information on epidemiology, antifungal susceptibilities, and correlation with clinical outcomes is lacking, and such information is useful from a prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic viewpoint.

In the present study, the main genotypically identified species complex was FSSC (F. solani, in 88% of patients). Another study performed in the same institution 8 years earlier found a similar frequency (91%).Citation7 Morphology-based identification showed that 85% of the isolates belonged to the F. solani species. One isolate that was morphologically classified as F. dimerum, when identified afterwards by genotyping, was shown to be FSSC. Further, two isolates morphologically identified as F. oxysporum were genotypically classified as belonging to the Fusarium genus but did not group in any species complex. Overall, the accuracy of morphologic identification, performed in the present study by a mycology laboratory, was 97.6%. In a previous study by the same author, a discrepancy of up to 50% between morphology-based and genotype-based identification was found when species-specific morphologic identification was performed by a general microbiology laboratory.Citation9 In that study, based on morphologic identification, a shift occurred toward mistakenly identifying F. oxysporum instead of F. solani.

Most of the patients affected were male (83%) and in a productive age group (mean 46 years), which agrees with several other studies of fungal keratitis.Citation6,Citation22,Citation23 This is probably due to the fact that males, particularly those of working age, are more involved in outdoor activities, with greater exposure to foreign bodies and trauma.

Comparing outcomes between the different species of Fusarium in this study, the only significant difference was a greater need for therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty with F. solani isolates when compared with F. oxysporum and F. dimerum isolates (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.05). Another study performed by the same authors in South Florida also demonstrated that F. solani isolates were associated with a higher rate of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty than other Fusarium species.Citation24 It has been demonstrated that F. solani has the capacity to form more biofilm than other species complexes.Citation25 The ability to form biofilm makes an isolate more resistant to antifungal agents than their planktonic counterparts without biofilm. F. solani biofilms have demonstrated reduced susceptibility, mainly for amphotericin B, which could in part explain the worse clinical outcomes for F. solani compared with other Fusarium species.

Of note, the majority of studies published on this subject and used for comparison describe outcomes for fungal keratitis in general, and not specifically for keratitis cases involving Fusarium species. The only study found in the literature which shows outcomes specifically for Fusarium keratitis was performed by Alfonso et al.Citation26

In the present study, final visual outcomes were poor, with a mean final BCVA of 1.60 LogMAR (20/800), ranging from 20/25 to light perception. Final BCVA was ≥20/40 in only 11% and ≤20/200 in 64% of the patients. Another study performed in Brazil also showed poor final BCVA of >20/40 in 28% of patients and <20/200 in 63%.Citation5 We identified much better final BCVA results in studies performed in other countries. In a Chinese study of early surgical intervention, final BCVA was ≥20/40 in 47% of patients and ≤20/200 in only 4%.Citation4 Two studies in the US also showed data on visual acuity, ie, 56% of patients in a North Florida study had ≥20/40, and 65% in a South Florida study had ≥20/50 and 18% <20/100.Citation26,Citation27

Therapeutic grafts were necessary in this study for 22 patients (54%). Another study in Brazil had a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty rate of 38%.Citation5 This is a high incidence when compared with studies carried out in developed countries, which show a need for penetrating keratoplasty in 21%–25% of cases.Citation27–Citation30 On the other hand, in developing countries, there is still a high need for penetrating keratoplasty to treat fungal keratitis cases, being necessary in 40%–47% in IndiaCitation13,Citation31 and performed in 88% of severe cases in a study from People’s Republic of China.Citation4

Mean time to diagnosis, defined as the interval from symptom onset until a specific diagnosis was made, was 19 (3–90) days. This is a long interval, considering that each day of delay decreases the chance of a good visual outcome. As our institution is a reference center, many cases only reach a specific diagnosis and treatment after being treated by one or more general physicians or ophthalmologists. In one study performed in the US, a mean time to diagnosis of 9 days was found.Citation26 Another study from the US found a mean time to presentation of 9 days.Citation27 Another study from People’s Republic of China showed a mean time to presentation of 27 days.Citation4 A study from India found that patients with a time to presentation of more than 10 days had statistically significant higher rate of surgical intervention, mostly due to corneal perforation.Citation31

Trauma was found to be the main risk factor in our study, being documented in 51% of patients. Of these, 62% were from organic sources. Other studies in Brazil and abroad corroborate this finding, and it is well known that trauma and foreign bodies are an important source of fungal ocular infections.Citation4–Citation6,Citation27,Citation30 Steroid use was found to be present in 15% of the patients. In other studies, it varied from 7% to 26%.Citation4,Citation26,Citation27

A low incidence of contact lens wear (5%) has been found among the patients we studied. Studies in developed countries, such as the US, show higher rates of contact lens wear among the risk factors, varying from 40% to 47%, and up to 52% during the contact lens-related outbreak in 2005–2006.Citation26,Citation27,Citation30 A study in People’s Republic of China, mostly involving rural patients, did not identify a history of contact lens wear in any of 654 cases of fungal keratitis.Citation4 This demonstrates a worldwide variation in the prevalence of contact lens-related fungal keratitis, and in Brazil, as in People’s Republic of China and other developing countries, contact lens wear is a less frequent risk factor for fungal keratitis, with trauma still being the most important one.

A long time to cure was also found, being 110 days on average. Fungal ulcers typically take a longer time to heal than bacterial ulcers. The long time to diagnosis found in this study may be one of the main factors implicated in increasing the severity of the disease and prolonging the time to cure. This outcome was found to be shorter in studies performed in the US, ranging from 53 to 67 days.Citation26–Citation28

In our study, the results of in vitro susceptibility tests ( and ) demonstrated mostly high MIC levels to available antifungal agents among Fusarium species, particularly when compared with published susceptibility profiles for other fungi, such as Aspergillus and Candida species.Citation32,Citation33

Antifungal sensitivity was not significantly different between species of Fusarium, probably due to the small number of non-F. solani isolates. Amphotericin B was the study drug with the lowest MIC levels against Fusarium isolates (MIC90 2 μg/mL), as seen in other susceptibility studies in the US (2 μg/mL),Citation34,Citation35 Italy (2 μg/mL),Citation36 and People’s Republic of China (2 μg/mLCitation4 and 4 μg/mLCitation37). Natamycin had an MIC90 of 8 μg/mL in our study, which varied by one dilution in other studies (4 μg/mLCitation22,Citation35 for isolates from the US and India, and 8 μg/mL and 16 μg/mL for two other studies in India).Citation14,Citation15 In the present study, voriconazole had a MIC90 of 16 μg/mL. Other studies testing voriconazole for Fusarium species found an MIC90 as low as 4 μg/mL in US,Citation34 8 μg/mL in Italy,Citation36 and 16 μg/mL in People’s Republic of China.Citation37 This shows the high MICs for antifungals needed to treat Fusarium species in general, especially for voriconazole. Other fungi, including Aspergillus and Candida species, are more susceptible than Fusarium species to azoles, particularly voriconazole.Citation32

In the present study, the MIC90 for natamycin was 8 μg/mL and for amphotericin B was 2 μg/mL for the tested isolates. Due to the inherent toxicity of amphotericin B eye drops, the commonly used topical concentration for this drug is 0.15% (1.5 mg/mL), whereas it is 5% (50 mg/mL) for natamycin. In this study, this difference of about 30 times between natamycin and amphotericin B concentrations and a difference of only two dilutions in MIC90 between them suggests that natamycin eyedrops should be used as the first-line antifungal agent for Fusarium keratitis at our institution.

Interestingly, an association was found between higher MIC levels for natamycin and need for therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty due to corneal perforation. A recent study from a fungal corneal ulcer trial in India also showed that higher MICs for natamycin and voriconazole were associated with an increased chance of corneal perforation.Citation14

Previous studies have demonstrated that lower MICs are correlated with better outcomes because re-epithelialization occurs earlier in those cases.Citation14,Citation15 Isolates with higher MICs are more difficult to treat and take more time to respond to therapy. Poor penetration of antifungal agents in the corneal stroma is also a limiting factor for rapid clearance of infection.Citation38 Taken together, higher MIC levels and the typically poor tissue penetration of antifungals hamper achievement of pharmacodynamic targets and therapeutic levels of these drugs, contributing to worse clinical outcomes.

In Brazil, natamycin and amphotericin B are the mainstay of treatment for fungal corneal ulcers. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that there may be association between higher natamycin MICs and higher incidence of corneal perforation. These data corroborate the fact that antifungal susceptibility testing may be important to guide treatment of cases with Fusarium keratitis.

Because of the inherent limitations in a retrospective study, the clinical data were incomplete in some cases, specifically for risk factors and some follow-up information. Only a small sample size of non-F. solani isolates was available due to the high prevalence of F. solani in Brazil. In future studies, a larger number of isolates from all species may provide more power for interspecies comparisons involving Fusarium.

Conclusion

In the present study, we investigated the epidemiologic data for genotyped isolates from Fusarium keratitis at a reference center in Brazil. Trauma was the main risk factor (51%), and therapeutic penetrating keratoplasties were necessary in 54% of patients. Poor follow-up BCVA (mean 20/800) was demonstrated, along with a long mean time to diagnosis (19 ± 12 days) and mean time to cure (110 ± 72 days). We also performed antifungal susceptibility tests and correlated these with clinical outcomes. Amphotericin B had the lowest MIC90 (2 μg/mL) of the three antifungal agents tested. There was an association between higher natamycin MIC levels and corneal perforation. Our study shows that Fusarium keratitis has a poor outcome, especially in developing countries, and suggests that more resistant strains have a higher risk of perforation, emphasizing the need for antifungal susceptibility testing and the tailoring of antifungal strategies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FurlanettoRLAndreoEGFinottiIGEpidemiology and etiologic diagnosis of infectious keratitis in Uberlandia, BrazilEur J Ophthalmol20102049850320175055

- CarielloAJPassosRMYuMCMicrobial keratitis at a referral center in BrazilInt Ophthalmol20113119720421448786

- ChowdharyASinghKSpectrum of fungal keratitis in North IndiaCornea20052481515604861

- XieLZhongWShiWSpectrum of fungal keratitis in north ChinaOphthalmology20061131943194816935335

- IbrahimMMVaniniRIbrahimFMEpidemiologic aspects and clinical outcome of fungal keratitis in southeastern BrazilEur J Ophthalmol20091935536119396778

- Hofling-LimaALForsetoADupratJPLaboratory study of the mycotic infectious eye diseases and factors associated with keratitisArq Bras Oftalmol200568212715824799

- GodoyPCanoJGeneJGenotyping of 44 isolates of Fusarium solani, the main agent of fungal keratitis in BrazilJ Clin Microbiol2004424494449715472299

- O’DonnellKSarverBABrandtMPhylogenetic diversity and microsphere array-based genotyping of human pathogenic Fusaria, including isolates from the multistate contact lens-associated US keratitis outbreaks of 2005 and 2006J Clin Microbiol2007452235224817507522

- OechslerRAFeilmeierMRLedeeDUtility of molecular sequence analysis of the ITS rRNA region for identification of Fusarium spp. from ocular sourcesInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci2009502230223619136697

- ChenAPrajnaLSrinivasanMDoes in vitro susceptibility predict clinical outcome in bacterial keratitis?Am J Ophthalmol200814540941218207124

- LalithaPSrinivasanMManikandanPRelationship of in vitro susceptibility to moxifloxacin and in vivo clinical outcome in bacterial keratitisClin Infect Dis2012541381138722447793

- KayeSTuftSNealTBacterial susceptibility to topical antimicrobials and clinical outcome in bacterial keratitisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20105136236819684005

- PradhanLSharmaSNalamadaSNatamycin in the treatment of keratomycosis: correlation of treatment outcome and in vitro susceptibility of fungal isolatesIndian J Ophthalmol20115951251422011503

- LalithaPPrajnaNVOldenburgCEOrganism, minimum inhibitory concentration, and outcome in a fungal corneal ulcer clinical trialCornea20123166266722333662

- ShapiroBLLalithaPLohARSusceptibility testing and clinical outcome in fungal keratitisBr J Ophthalmol20109438438520215380

- ScottIUScheinODWestSFunctional status and quality of life measurement among ophthalmic patientsArch Ophthalmol19941123293358129657

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards InstituteReference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungiApproved Standard M38-A22nd edWayne, PAClinical and Laboratory Standards Institute2008

- TamuraKDudleyJNeiMMEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0Mol Biol Evol2007241596159917488738

- PosadaDjModelTest: phylogenetic model averagingMol Biol Evol2008251253125618397919

- HuelsenbeckJPRonquistFMRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic treesBioinformatics20011775475511524383

- MaddisonDRTesting monophyly of a group of beetlesStudy 1 in Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis, version 1.042004 Available from: http://mesquiteproject.org/mesquite2.0/Mesquite_Folder/docs/mesquite/studies/study001/index.htmlAccessed June 19, 2013

- LalithaPVijaykumarRPrajnaNVIn vitro natamycin susceptibility of ocular isolates of Fusarium and Aspergillus species: comparison of commercially formulated natamycin eye drops to pharmaceutical-grade powderJ Clin Microbiol2008463477347818701666

- WongTYNgTPFongKSRisk factors and clinical outcomes between fungal and bacterial keratitis: a comparative studyCLAO J1997232752819348453

- OechslerRAFeilmeierMRMillerDFusarium keratitis: genotyping, in vitro susceptibility and clinical outcomesCornea20133266767323343947

- MukherjeePKChandraJYuCCharacterization of Fusarium keratitis outbreak isolates: contribution of biofilms to antimicrobial resistance and pathogenesisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci2012534450445722669723

- AlfonsoECCantu-DibildoxJMunirWMInsurgence of Fusarium keratitis associated with contact lens wearArch Ophthalmol200612494194716769827

- IyerSATuliSSWagonerRCFungal keratitis: emerging trends and treatment outcomesEye Contact Lens20063226727117099386

- RitterbandDCSeedorJAShahMKFungal keratitis at the New York Eye and Ear InfrmaryCornea20062526426716633023

- TanureMACohenEJSudeshSSpectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCornea20001930731210832689

- KeayLJGowerEWIovienoAClinical and microbiological characteristics of fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001–2007: a multicenter studyOphthalmology201111892092621295857

- RautarayaBSharmaSKarSDiagnosis and treatment outcome of mycotic keratitis at a tertiary eye care center in eastern IndiaBMC Ophthalmol201111394622188671

- Espinel-IngroffAIn vitro activity of the new triazole voriconazole (UK-109,496) against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and common and emerging yeast pathogensJ Clin Microbiol1998361982029431946

- Espinel-IngroffABoyleKSheehanDJIn vitro antifungal activities of voriconazole and reference agents as determined by NCCLS methods: review of the literatureMycopathologia200115010111511469757

- MarangonFBMillerDGiaconiJAIn vitro investigation of voriconazole susceptibility for keratitis and endophthalmitis fungal pathogensAm J Ophthalmol200413782082515126145

- ReubenAAnaissieENelsonPEAntifungal susceptibility of 44 clinical isolates of Fusarium species determined by using a broth microdilution methodAntimicrob Agents Chemother198933164716492817867

- TortoranoAMPrigitanoADhoGSpecies distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibility patterns of 75 clinical isolates of Fusarium spp. from northern ItalyAntimicrob Agents Chemother2008522683268518443107

- WangHXiaoMKongFAccurate and practical identification of 20 Fusarium species by seven-locus sequence analysis and reverse line blot hybridization, and an in vitro antifungal susceptibility studyJ Clin Microbiol2011491890189821389150

- O’DayDMHeadWSRobinsonRDCorneal penetration of topical amphotericin B and natamycinCurr Eye Res198658778823490954