Abstract

Background

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is often associated with blinding ocular surface cicatricial sequelae. Recent reports have described markedly improved clinical outcomes with the application of amniotic membrane to the ocular surface during the acute phase. Here we describe the clinical outcome of a patient with acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and severe ocular surface involvement in whom the evolving medical condition and family consent resulted in amniotic membrane application to each eye at differing intervals from disease onset.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective chart review of a woman with Stevens-Johnson syndrome who presented within hours of disease onset. She underwent application of amniotic membrane to the ocular surface of the left eye during the hyperacute phase (<72 hours after disease onset) and to the right eye at a later time point during the acute phase (six days after disease onset). The clinical outcomes of the two eyes, as well as associated ocular symptoms, were compared over a one-year postoperative period.

Results

The right eye, treated later in the course of the disease, required additional surgical procedures and ultimately exhibited significantly more advanced ocular surface pathology than the left. Further, the patient reported more pronounced issues of chronic eye pain and visual difficulties in the right eye.

Conclusion

Earlier intervention with application of amniotic membrane to the ocular surface in this patient with severe ocular involvement secondary to Stevens-Johnson syndrome proved superior. Application of amniotic membrane as soon as possible after disease onset, preferably in the hyperacute phase, appears to result in a significantly better clinical outcome than application later in the disease course.

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and its more severe variant, toxic epidermal necrolysis, constitute acute vesiculobullous reactions, typically secondary to medications, involving the skin and mucous membranes. The ocular surface is one of the most commonly involved mucosal surfaces (69%–81% in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and 50%–67% in toxic epidermal necrolysis).Citation1,Citation2 If patients survive the often fatal acute stage, they commonly suffer devastating ocular sequelae, including symblepharon and other cicatricial conjunctival changes, limbal stem cell failure, and ultimately corneal opacification. These patients are often burdened with life-long debilitating chronic eye pain and severe visual impairment.Citation1–Citation5

Several case reports and series, as well as one case-control study, have demonstrated improved outcomes with application of amniotic membrane to the ocular surface during the acute phase of the disease.Citation6–Citation19 However, while the positive effect of this intervention has been clearly documented, the optimal timing of application during the acute phase has not been clarified. Given that there are no universally accepted definitions for the stages of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, we will define, for the purpose of this report, the hyperacute phase as <72 hours after disease onset, the acute phase as 72 hours to four weeks after disease onset, and the chronic phase as more than four weeks after disease onset. Here we report the unique situation of a patient in whom application of amniotic membrane was performed during the hyperacute phase in one eye, and at a later time point during the acute phase in the other eye, with markedly different clinical outcomes.

Case report

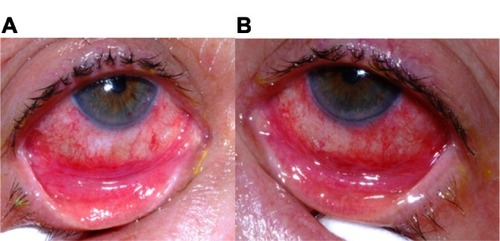

A 70-year-old woman, who had recently been started on allopurinol for gout, presented with a one-day history of bilateral eye pain, moderate conjunctival injection (), and oral mucosal sloughing. She was admitted to hospital for presumed Stevens-Johnson syndrome, which was later confirmed with a skin biopsy. Hourly topical corticosteroid application (fluorometholone ointment, FML® 0.1%, Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA), as well as topical antibiotic prophylaxis, was initiated in both eyes. No systemic steroids or other immunomodulators were administered. The patient’s systemic condition worsened over the next 48 hours and she was intubated secondary to respiratory distress. Her ophthalmic situation also progressed, with evidence of increased conjunctival injection, new bulbar conjunctival epithelial defects, and sloughing of the eyelid margin epithelium ( and ). Given the significant ophthalmic involvement and progression despite aggressive topical steroids, application of amniotic membrane was recommended. A family meeting extensively considered the risks and benefits of treatment and it was decided initially to treat only the left eye with amniotic membrane.

Figure 1 Patient with acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome, at the time of initial presentation to hospital and before initiation of treatment, showing conjunctival injection in both eyes.

Figure 2 Patient’s ophthalmic appearance at 2.5 days (60 hours) after disease onset. (A) The right eye demonstrates evidence of marked conjunctival injection. The right eye also shows defects in the bulbar conjunctival epithelium and epithelial sloughing of the eyelid margin. (B) The left eye shows similarly severe ophthalmic involvement.

Application of amniotic membrane to the ocular surface was performed at the bedside instead of in the operating room at the request of the medical team. Cryopreserved amniotic membrane (AmnioGraft®, BioTissue, Miami, FL, USA) was applied to cover the entire palpebral conjunctival surface and both lower and upper eyelid margins completely, and was secured with 8-0 nylon running sutures and 6-0 polypropylene sutures as previously described.Citation20 A Prokera® device (BioTissue, Miami, FL, USA), ie, amniotic membrane mounted on a polycarbonate ring, was used to cover the cornea as well as the perilimbal bulbar conjunctiva.

The treated left eye stabilized over the next few days, while the untreated right eye progressed, with development of pseudomembranes and early symblepharon formation. Given this progression, application of amniotic membrane was performed on the right eye on the sixth day after disease onset using the technique described above.

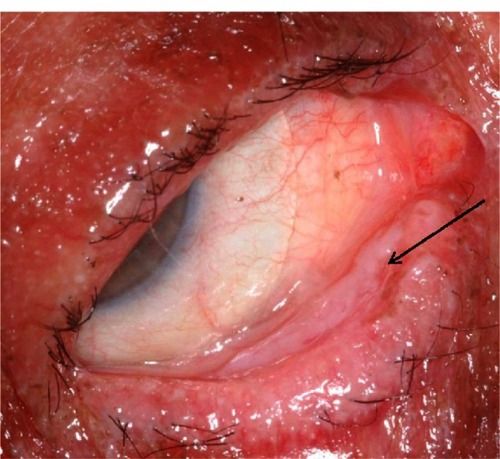

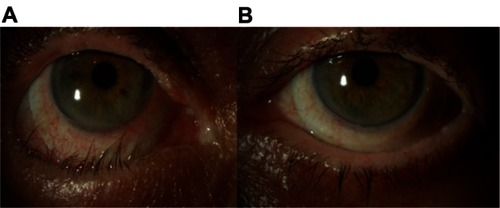

Ophthalmic examination at the five-week mark following disease onset revealed a significant difference in the clinical appearance of the two eyes. The right eye exhibited a right lower lid cicatricial entropion with associated palpebral conjunctival cicatrix (), trichiasis, and breakdown of the corneal epithelium. The patient also reported more visual difficulties and symptoms of irritation in the right eye. Surgery to remove the cicatrix and normalize the eyelid position proved unsuccessful. The eye ultimately required fitting with a Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem device (Boston Foundation for Sight, Needham, MA, USA), a fluid-filled scleral lens, in order to afford protection of the cornea from lid-induced and lash-induced mechanical trauma (). In contrast, the left eye revealed normal upper and lower eyelid positions, no trichiasis, and an intact corneal epithelium ().

Figure 3 Right lower fornix of the patient five weeks after disease onset. Evident is a contracted tarsal conjunctival membrane (arrow) resulting in cicatricial entropion, trichiasis, and corneal epithelial breakdown.

Figure 4 Patient showing a significant difference in clinical appearance of the right and left eyes four months after disease onset. (A) The right eye demonstrates a cicatricial entropion with associated trichiasis and conjunctival injection. A fluid-filled scleral lens (PROSE device) is in place. (B) The left eye demonstrates normal upper and lower eyelid positions without evidence of trichiasis. A PROSE device is also visible.

Discussion

Blinding ocular sequelae are the most devastating long-term consequences for survivors of an acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis episode. Traditional supportive treatments, such as lubricating agents and periodic symblepharon lysis with a glass rod, generally do little to improve the dismal prognosis. Further, patients with these chronic ocular sequelae are left with limited treatment options,Citation21 most of them rarely successful.

In recent times, the focus has been on more aggressive intervention during the acute phase to limit the damage to the ocular surface wrought by the acute inflammatory process. Use of pulsed intravenous steroids has been described,Citation22,Citation23 but this treatment approach remains controversial due to concerns about possible septic and other systemic complications.Citation24,Citation25

Amniotic membrane, believed to have antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects, as well as beneficial effects on epithelialization,Citation26 applied to the ocular surface during the acute phase has been associated with promising results. The application is often combined with application of topical or subconjunctival depot corticosteroids. The evidence indicates that this approach is both effective and associated with less risk of systemic complications, given its local nature. When applying amniotic membrane during the acute phase, it is important to cover as much of the denuded and inflamed surface as possible (corneal surface, bulbar conjunctiva, palpebral conjunctiva, and eyelid margins). Techniques have been described for application in the operating room, utilizing an operating room microscope, as well as at the bedside, for patients unable to be transferred to the operating room.Citation20 The latter was the approach used in the patient described in this report.

The window of opportunity in the acute phase during which it is possible to achieve a positive effect with application of amniotic membrane has not been clearly defined to date, but recent experience suggests it is probably in the days, not weeks, after disease onset, ie, after the surface becomes denuded but before the fibrinous inflammatory exudate consolidates and forms a cicatrix or symblepharon.

In the patient described in this report, amniotic membrane was applied to the left eye in the hyperacute phase of the disease. This effectively stabilized the inflammatory process and enhanced re-epithelialization of the ocular surface, likely minimizing further damage in that eye. The right eye, treated later in the acute phase with amniotic membrane, showed progressive inflammatory changes and formation of epithelial defects on the ocular surface. Ultimately, the right eye showed significantly more cicatricial sequelae, specifically entropion formation with trichiasis, associated corneal epithelial breakdown, and resultant eye pain and impaired vision. Even a short delay in treatment, in this case a few days, made a significant difference to the final clinical outcome.

Although our report consists of only a single patient, this patient’s situation of having both eyes treated at different time points provides a unique opportunity and, given the favorable results with amniotic membrane now being widely reported, it is unlikely that a similar case will become available for analysis. While one or two days after a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis may be used to determine the degree of ophthalmic involvement and the response to medical therapy alone, once severe ocular involvement and/or continued progression is evident, it appears that further intervention without delay is indicated. A better understanding of the critical nature of timing in regard to intervention with application of amniotic membrane in acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis will serve to improve ophthalmic outcomes further in these devastating blinding diseases.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a Research to Prevent Blindness grant.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChangYSHuangFCTsengSHHsuCKHoCLSheuHMErythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: acute ocular manifestations, causes, and managementCornea200726212312917251797

- PowerWJGhoraishiMMerayo-LlovesJNevesRAFosterCSAnalysis of the acute ophthalmic manifestations of the erythema multiforme/Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis disease spectrumOphthalmology199510211166916769098260

- De RojasMVDartJKSawVPThe natural history of Stevens Johnson syndrome: patterns of chronic ocular disease and the role of systemic immunosuppressive therapyBr J Ophthalmol20079181048105317314145

- YipLWThongBYLimJOcular manifestations and complications of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: an Asian seriesAllergy200762552753117313402

- López-GarcíaJSRivas JaraLGarcía-LozanoCIConesaEde JuanIEMurube del CastilloJOcular features and histopathologic changes during follow-up of toxic epidermal necrolysisOphthalmology2011118226527120884054

- Di PascualeMAEspanaEMLiuDTCorrelation of corneal complications with eyelid cicatricial pathologies in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndromeOphthalmology2005112590491215878074

- GregoryDGTreatment of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: a review of 10 consecutive casesOphthalmology2011118590891421440941

- JohnTFoulksGNJohnMEChengKHuDAmniotic membrane in the surgical management of acute toxic epidermal necrolysisOphthalmology2002109235136011825823

- KobayashiAYoshitaTSugiyamaKAmniotic membrane transplantation in acute phase of toxic epidermal necrolysis with severe corneal involvementOphthalmology2006113112613216324747

- MuqitMMEllinghamRBDanielCTechnique of amniotic membrane transplant dressing in the management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndromeBr J Ophthalmol20079111153617947270

- TandonACackettPMulvihillAFleckBAmniotic membrane grafting for conjunctival and lid surface disease in the acute phase of toxic epidermal necrolysisJ AAPOS200711661261317681814

- ShammasMCLaiECSarkarJSYangJStarrCESippelKCManagement of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis utilizing amniotic membrane and topical corticosteroidsAm J Ophthalmol2010149220321320005508

- RubinateLWelchMNJohnsonAJDeMartelaereSLNew technique for manufacture and placement of enlarged symblepharon ring with amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface protection in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis2010 ARVO eabstract 1135

- HsuMJayaramAVernerRLinABouchardCIndications and outcomes of amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case-control studyCornea201231121394140223135531

- KolomeyerAMDoBKTuYChuDSPlacement of Prokera in the management of ocular manifestations of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an outpatientEye Contact Lens672012 [Epub ahead of print.]

- HessTMChewHFSuccessful treatment of acute ocular involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome with amniotic membrane transplantation: a case reportCan J Ophthalmol2012476e44e4623217513

- BaruaAMcKeeHDBarbaraRCarleyFBiswasSToxic epidermal necrolysis in a 15-month-old girl successfully treated with amniotic membrane transplantationJ AAPOS201216547848023084389

- TomlinsPJParulekarMVRauzS“Triple-TEN” in the treatment of acute ocular complications from toxic epidermal necrolysisCornea201332336536922677638

- HonavarSGBansalAKSangwanVSRaoGNAmniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction in Stevens-Johnson syndromeOphthalmology2000107597597910811093

- GregoryDGThe ophthalmologic management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndromeOcul Surf200862879518418506

- LetkoEPapaliodisDNPapaliodisGNDaoudYJAhmedARFosterCSStevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literatureAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200594441943615875523

- ArakiYSotozonoCInatomiTSuccessful treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onsetAm J Ophthalmol200914761004101119285657

- SotozonoCUetaMKoizumiNDiagnosis and treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis with ocular complicationsOphthalmology2009116468569019243825

- RasmussenJEErythema multiforme in children. Response to treatment with systemic corticosteroidsBr J Dermatol1976952181186952755

- HalebianPHShiresGTBurn unit treatment of acute, severe exfoliating disordersAnnu Rev Med1989401371472658743

- TsengSCEspanaEMKawakitaTHow does amniotic membrane work?Surf200423177187