Abstract

Introduction

The management of large pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) associated with retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP) remains a challenge due to the high risk of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tear. We describe the successful progressive anatomical result and the maintenance of visual acuity to bimonthly, half-dose ranibizumab in a patient with this condition.

Purpose

To describe the management of a large PED secondary to RAP with bimonthly, half-dose ranibizumab.

Method

Case report.

Patient

A 71-year-old woman presented with visual symptoms due to an enlarged PED, compared with previous visits, secondary to a RAP lesion, with a visual acuity of 20/32. To reduce the risk of an RPE tear and a significant decrease in vision, we discussed with the patient the possibility of treating the lesion in a progressive manner, with more frequent but smaller doses of ranibizumab. The patient was treated biweekly with 0.25 mg of ranibizumab until fattening of the PED.

Results

The large PED fattened progressively, and visual acuity was preserved with no adverse events.

Discussion

The use of half-dose antiangiogenic therapy may be useful in managing large vascularized PED associated with RAP, in an attempt to reduce the risk of RPE tear.

Introduction

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tear is a major concern in the management of large pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) secondary to exudative age-related macular degeneration. Although large PEDs can be associated with occult choroidal neovascularization (CNV), they also frequently occur with retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP) lesions,Citation1 a special form of wet age-related macular degeneration that accounts for approximately 10%–15% of the cases of the disease.Citation2

There are a number of treatments that are not effective in RAP lesions, including photodynamic therapy with or without steroids. Fortunately, these lesions have had a better prognosis since the advent of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy, although there is a need for continuous treatment due to the recurring nature of these lesions.Citation3,Citation4 Unfortunately, as with other therapies, there is a high incidence of RPE tears after antiangiogenic treatment of vascularized PED in RAP lesions (reaching 36.8% in a recent series),Citation5 with most patients becoming legally blind.Citation1 The high incidence rate of RPE tears after initiating anti-VEGF therapyCitation6,Citation7 suggests that, at least in some cases, RPE tears can be induced by the treatment.

The size of the PED has been reported as the single most important predictor of RPE tear after treatment with intravitreal anti-VEGF.Citation6,Citation8 It has been proposed that RPE tears may occur due to stretching forces on a weakened RPECitation9,Citation10 or to retraction of the CNV secondary to anti-VEGF therapy. In this case, using a lower dose might decrease the risk of an RPE tear.

We present the case of a patient with a large PED associated with a RAP lesion. To decrease the risk of an RPE tear, we used half-dose ranibizumab 0.25 mg every 2 weeks until fattening of the PED, followed by regular dosing according to clinical judgment.

Case report

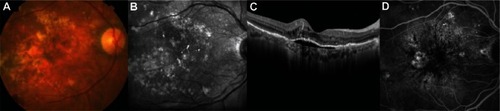

A 71-year-old Caucasian female with a large, stable, subfoveal serous PED in the right eye (RE) and early age-related macular degeneration with confluent drusen in the left eye (LE) had been monitored since March 2008 (–). Her baseline best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/25 in the RE and 20/20 in the LE. Due to the stability of the lesion and the good BCVA, the patient had been observed for 45 months with no treatment.

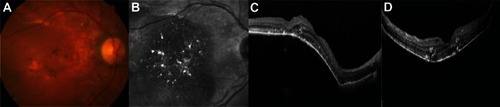

Figure 1 (A–D) Fundus photography, infrared imaging, spectral domain optical coherence tomography, and fluorescence angiography 3 months before visual symptoms. There is a subfoveal pigment epithelial detachment with minimal subretinal fluid.

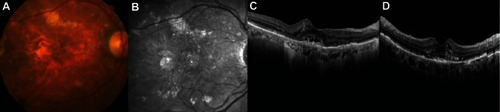

In February 2012, the patient noticed metamorphopsia and decreased vision and came for consultation. Her BCVA in the RE dropped to 20/40 and remained basically unchanged in the LE. The PED increased in size and there were intraretinal cystic changes. The findings on spectral domain optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography were suggestive of a RAP lesion (–).

Figure 2 (A–D) The patient complained of sudden metamorphopsia and decreased vision. The pigment epithelial detachment has increased and there is cystoid macular edema. These findings are suggestive of a vascularized pigment epithelial detachment caused by retinal angiomatous proliferation.

The high risk of an RPE tear and visual loss after intravitreal injection of any anti-VEGF therapy was discussed with the patient. A less aggressive approach was proposed, which involved a decreased dose and a more frequent regimen of ranibizumab in order to lower the biological stress on the PED.

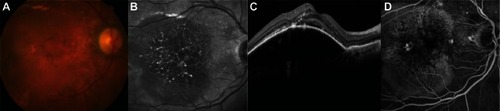

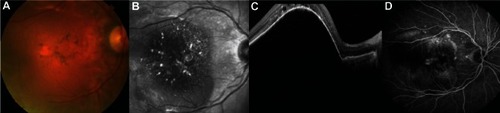

After four biweekly injections of 0.25 mg of ranibizumab, the PED flattened progressively and there were no ocular adverse events, specifically no RPE tears (– and –). From then on, the patient was treated monthly due to a lack of complete resolution of intraretinal fluid with the conventional 0.5 mg dose. At the last visit, on November 2012, metamorphopsia was unnoticeable, BCVA remained at 20/40, and there was a marked anatomic improvement (–).

Figure 3 (A–D) Fifteen days after the first injection, there is a slight improvement in pigment epithelial detachment height.

Discussion

The management of large PEDs is controversial due to the wide range of BCVA in these patients and the variable natural course of the condition (stability of the PED over many months, collapse and progression toward RPE atrophy, conversion from serous to vascularized PED, or spontaneous RPE tears have all been described). Additionally, the response to treatment is often unpredictable. Furthermore, the current therapeutic strategies can trigger some adverse events that worsen the functional and anatomical status of the patient, and RPE tears are high in the rank of such complications. Although full-dose ranibizumab given monthly would have achieved the same effect in flattening the retina, the risk of complications such as RPE tear and subsequent visual loss must be taken into account when managing these patients.

To avoid the occurrence of such complications, we managed the patient with a two-step approach:

First, we decreased the dose of ranibizumab by half but injected it twice as frequently (biweekly). The mechanism of action of this approach may be two-fold. First, a lower volume of intravitreal fluid may decrease the mechanical stress on the RPE by making the flattening smoother and more gradual. Second a decreased concentration of ranibizumab may have a less intense effect on the contraction of the neovascular tissue, avoiding its acute regression and the tension this may transfer to the outer side of the RPE, where CNV may be adherent. Both mechanisms may be acting simultaneously to achieve the desired effect. The biweekly administration accomplishes the net monthly delivery of 0.5 mg of ranibizumab, according to current guidelines, and should ensure a therapeutic dose in the outer retina.

Second we reintroduced the pro re nata strategy with the 0.5 mg dose to address the retinal portion of the lesion once the PED was flattened and the risk of an RPE tear decreased.

In summary, more frequent half dosing of anti-VEGF drugs may retain a therapeutic effect while minimizing the incidence of RPE tears in patients with large vascularized PED. This strategy merits further consideration in the therapeutic armamentarium for this condition.

Disclosure

Financial support: Barcelona Macula Foundation. Financial disclosure: Jordi Monés: consultant/adviser: Novartis, Bayer, Allergan, Ophthotech, Notalvision, Allimera; grant support: Novartis, Bayer, Ophthotech; lecture fees: Novartis, Bayer, Allergan, Ophthotech. Marc Biarnés: lecture fees: Novartis. Josep Badal: none.

References

- GutfleischMHeimesBSchumacherMDietzelMLommatzschABirdALong-term visual outcome of pigment epithelial tears in association with anti-VEGF therapy of pigment epithelial detachment in AMDEye (Lond)20112591181118621701525

- GrossNEAizmanABruckerAKlancnikJMJrYannuzziLANature and risk of neovascularization in the fellow eye of patients with unilateral retinal angiomatous proliferationRetina200525671371816141858

- MeyerleCBFreundKBIturraldeDSpaideRFSorensonJASlakterJSIntravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for retinal angiomatous proliferationRetina200727445145717420697

- GhaziNGKnapeRMKirkTQTiedemanJSConwayBPIntravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of retinal angiomatous proliferationRetina200828568969518463511

- IntroiniUTorres GimenoAScottiFSetaccioliMGiatsidisSBandelloFVascularized retinal pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration: treatment and RPE tear incidenceGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol201225091283129222350060

- ChangLKSarrafDTears of the retinal pigment epithelium: an old problem in a new eraRetina200727552353417558312

- CunninghamETJrFeinerLChungCTuomiLEhrlichJSIncidence of retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal ranibizumab injection for neovascular age-related macular degenerationOphthalmology2011118122447245221872935

- LeitritzMGeliskenFInhoffenWVoelkerMZiemssenFCan the risk of retinal pigment epithelium tears after bevacizumab treatment be predicted? An optical coherence tomography studyEye (Lond)200822121504150718535608

- LafautBAAisenbreySVanden BroeckeCKrottRJonescu-CuypersCPReyndersSClinicopathological correlation of retinal pigment epithelial tears in exudative age related macular degeneration: pretear, tear, and scarred tearBr J Ophthalmol200185445446011264137

- PauleikhoffDLoffertDSpitalGRadermacherMDohrmannJLommatzschAPigment epithelial detachment in the elderly. Clinical differentiation, natural course and pathogenetic implicationsGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol2002240753353812136282