Abstract

Purpose

To describe the different corneal pathologies and determine the prevalence of corneal blindness amongst children aged 0–15 years, seen at the ophthalmology unit of a tertiary hospital in Cameroon.

Patients and methods

The medical records of all patients who presented to the Ophthalmic Unit between 2002 and 2010 were reviewed, retrospectively. The records of children aged 0–15 years, presenting with corneal pathologies, were further reviewed. Data collected included age, sex, past medical history, initial visual acuity, type of corneal lesion, and visual acuity at last follow-up.

Results

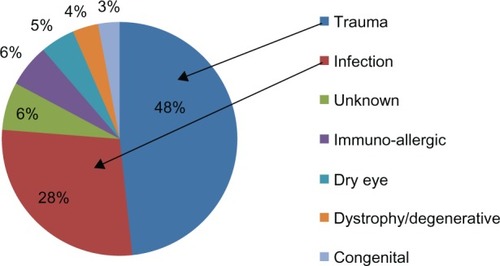

Of the 7,922 children seen over the study period, 168 had corneal pathologies: a prevalence of 2.1%. Males were more affected than females (male to female ratio: 1.4:1; P = 0.008). The age range was from 2 weeks to 15 years (mean age: 7.1 years; standard deviation: 4.4 years). The leading etiologies were trauma (48.2%; n = 81) and infection (28.0%; n = 47). Amongst those with available follow-up data, visual impairment and blindness occurred in 50% of the cases (n = 12), with one case being bilateral.

Conclusion

Trauma is the most frequent cause of corneal blindness in children.

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood blindness in low income countries is estimated by the World Health Organization at 1.5 per 1,000 children.Citation1 In sub-Saharan Africa, corneal pathologies account for 31% of cases.Citation1 Their causes include vitamin A deficiency, ophthalmia neonatorum, and the use of traditional eye medicine (TEM).Citation2

In Cameroon, the cornea has been reported as the leading site of abnormality in schools for the blind,Citation3 although hospital-based studies on childhood blindness have reported other sites.Citation4,Citation5 This study aims to describe the different corneal diseases and to determine the prevalence of corneal blindness amongst children seen at a tertiary hospital.

Material and methods

This was a retrospective study (2002–2010) that was approved by the Yaoundé Gynaeco-Obstetric and Paediatric Hospital’s ethical committee. The records of children aged 0–15 years who presented with corneal pathologies were reviewed. The data collected included age, sex, past history, delay in presentation (duration between onset of symptoms and presentation), initial visual acuity, type of corneal lesion, and visual acuity at last follow-up. Cases with corneal involvement resulting from an intraocular disease, such as glaucoma, were excluded. The World Health Organization’s definition of blindness was used: “corrected visual acuity in the better eye of less than 1/20.”Citation1 Data analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

A total of 29,685 new patients were seen, including 7,922 children. Corneal pathologies were seen in 168 children, giving a prevalence of 2.1% (). There were 98 males and 70 females, representing 2.6% and 1.74%, respectively, of the male and female children (). This difference was statistically significant when these proportions were compared using the chi-square test (P = 0.0086).

Table 1 Prevalence of corneal diseases in children

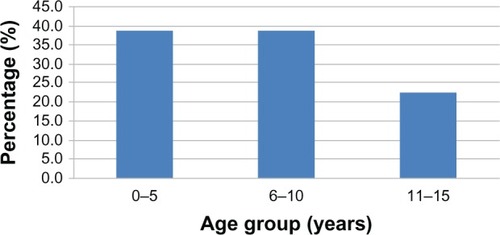

Ages ranged from 2 weeks to 15 years, with a mean (± standard deviation) of 7.1 ± 4.4 years and a median of 7.0 years. Children aged 0–5 years and 6–10 years, were the most represented groups (n = 65 for each) ().

Delay in presentation varied with the etiological category of the lesion. It was approximately 1 day for cases with chemical injury; 34 days for mechanical injury, with 25.7% (n = 18/70) examined within 24 hours following injury; 52 days for infections; and 1,827 days for dystrophies.

Predisposing factors included ocular trauma in 71 cases (43.3%); ocular surface infection, including conjunctivitis and blepharoconjunctivitis, in 15 cases (8.9%); the use of traditional eye medicine in eight cases (4.8%); systemic disease in two cases, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum (1.2%); family history of corneal dystrophy in two cases (1.2%); and ocular herpes in one case (0.6%).

Corneal pathology was unilateral in 86.3% of cases (n = 145) and bilateral in 13.7% (n = 23). The most frequent anatomical lesions were scars of unknown origin (16.1%) and superficial foreign bodies (14.3%). The most frequent etiologies of corneal pathologies were trauma (81 cases [48.2%]) and infection (47 cases [28.0%]) (). The diagnosis of corneal infection was clinical. Seven cases had a characteristic herpes simplex dendritic keratitis. Trauma was the most frequent etiology in all age groups, with the highest prevalence of 58.5% (n = 38) occurring amongst those aged 6–10 years. Infection was most common amongst those aged 0–5 years.

Initial visual acuity was not available in 59 cases (35.1%). Out of the 109 cases, 51% registered an initial visual acuity of ≥0.3 (). Follow-up data was available only in 34 cases (20.2%). The duration of follow-up ranged from 1–52 weeks. Visual acuity at last follow-up was available in 24 cases (while there was inability to cooperate in ten cases). Visual impairment and blindness were recorded in 12 cases (50%), with one case being bilateral (). Seven of the 12 cases (58.3%) resulted from trauma.

Table 2 Visual acuity at presentation and at last follow-up

Discussion

The prevalence of corneal pathology among the children in this study was 2.1%. Corneal pathologies are usually not amongst the most prevalent ophthalmic pathologies in children. Refractive errors, conjunctivitis, trauma, eyelid, and orbital pathologies are usually the most prevalent.Citation6–Citation9

Srinivas reported a prevalence of 26.3% amongst 4,022 Indian children aged 0–16 years.Citation10 Onabolu et al reported a prevalence of 42% amongst 169 children aged 0–16 years in The Gambia.Citation11 The difference in prevalence of corneal pathologies in this study, compared to the others, could be due to differences in the relative frequencies of specific entities. In The Gambia, vernal keratoconjunctivitis was reported in 22.5% of cases, as compared to 6% in this study. In the study from India, nutritional involvement represented 35.5% of the cases. No case of nutritional involvement was recorded in this study. This is due to the strategies put in place to combat vitamin A deficiency.

A significantly greater proportion of male than female children were affected by corneal pathologies. Srinivas reported a similar finding.Citation10 This can be explained by the fact that trauma is the leading cause of corneal pathologies in children; boys are usually more involved in outdoor play than girls, and indulge in more aggressive play, which predisposes them to injury.

Identifiable risk factors were detected in 58.9% of cases, with ocular trauma being the most predominant. Besides direct traumatic involvement, trauma has been identified as a risk factor for microbial keratitis.Citation12–Citation14 Contact lens wear was the most important risk factor for microbial keratitis in Taiwanese children.Citation15 The use of contact lenses is not common in our setting.

Late presentation of corneal pathologies was common. The mean time for presentation following mechanical injury was 34.3 days; 25.7% of cases were seen within 24 hours. In a study on ocular trauma in children in Douala,Citation16 55.5% of the children were seen within the first 24 hours. In a study from Ibadan,Citation17 Nigeria, 23.4% were seen within the first 24 hours. Accessibility of hospitals, the cost of medical care, and the use of self-medication and TEM could explain the delay in presentation. Late presentation and the use of TEM can lead to poor outcomes. This study did not specifically seek to determine the types of TEM used. However, it was noted that, compared to urban dwellers, rural dwellers used TEM more frequently. The use of TEM depends on customs and beliefs. TEM mainly uses plant extracts (Citrus aurantifolia, Allium cepa) and human breast milk. In a study on the use of TEM by corneal ulcer patients in South India, Prajna et al reported the use of TEM in 47.7% of cases.Citation18

The most frequent etiology was trauma (48.2% of cases). Onabolu et al also reported trauma as the most frequent etiology (32.4%).Citation11 Srinivas, however, reported nutritional involvement as the leading etiology, with trauma ranking fourth. Thirty-six (48.7%) trauma cases were in children aged 6–10 years. Al-Bdour and Azab also reported a preponderance of injury in this age group.Citation19 These are children of primary school age, who are physically more active. The lowest proportion of infective keratitis was from the 6–10 years age group (21.3%), and the highest (48.9%) from the 0–5 years age group. The age distribution of patients with childhood microbial keratitis from southern India shows a similar trend, with 18.9% from the 6–10 years age group.Citation14 In our setting, the diagnosis of infective keratitis is usually made on a clinical basis, given that most cases use eye drops containing antibiotics before presentation.

Considering visual acuity at last follow-up, 50% cases suffered visual impairment and blindness. Onabolu et al reported that 45% of children with corneal diseases suffered blindness from trauma and from congenital diseases.Citation11

Congenital diseases involving the cornea were uncommon (3%). No case was reported by Srinivas in India,Citation10 while Onabolu et al reported a prevalence of 16.9% in cases from The Gambia.Citation11 The most frequent congenital eye anomalies are cataract and glaucoma.Citation20,Citation21

This study is limited by the high number of patients lost to follow-up, and the lack of microbiology reports for cases with suspected microbial keratitis.

Conclusion

Although the prevalence is low, corneal pathology in children leads to poor visual outcomes. Major causes in our setting are avoidable. Thus, parents, childhood health care givers, teachers, and children should be educated on the prevention of ocular injury.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GilbertCFosterAChildhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020 – the right to sightBull World Health Organ200179322723211285667

- GilbertCFosterABlindness in children: control priorities and research opportunitiesBr J Ophthalmol2001851025102711520746

- NocheCDBellaALFréquence et causes de cécité et de déficiences visuelles dans des écoles de malvoyants à Yaoundé (Cameroun). [Frequency and causes of blindness and visual impairment in schools for the blind in Yaoundé, Cameroon]Santé2010203133138 French21118789

- BellaLAEballeAOKouamJMCécité et malvoyance bilatérales de l’enfant de 0 à 5 ans à l’hôpital gynéco-obstétrique et pédiatrique de Yaoundé. [Bilateral blindness and visual impairment in children aged 0–5 years in the women’s and children’s hospital of Yaoundé]Santé20102013539 French20348057

- EballeAOEpéeEKokiGBellaLMvogoCEUnilateral childhood blindness: a hospital-based study in Yaoundé, CameroonClin Ophthalmol2009346146419714264

- EballeAOBellaLAOwonoDMbomeSMvogoCELa pathologie oculaire de l’enfant âgé de 6 à 15 ans: étude hospitaliére à Yaoundé. [Eye disease in children aged 6 to 15 years: a hospital-based study in Yaoundé]Santé20091926166 French20031512

- OnakpoyaOHAdeoyeAOChildhood eye diseases in southwestern Nigeria: a tertiary hospital studyClinics (Sao Paulo)2009641094795219841700

- AjaiyeobaAChildhood eye diseases in IbadanAfr J Med Med Sci19942332272317604746

- OnyekonwuGCPattern of eye diseases In Nigerian children seen at Ebonyi State University Teaching Hospital (EBSUTH), Abakaliki, NigeriaEbonyi Med J2008747

- SrinivasCCorneal diseases as leading causes of blindness in Indian childrenShimuziKXIII Congress of the Asia-Pacific Academy of OphthalmologyKyotoExcerptaMedica199114

- OnaboluROOIwuoraNACeesayWCorneal diseases in children in The GambiaNiger J Ophthalmol2009171

- SinghGPalanisamyMMadhavanBMultivariate analysis of childhood microbial keratitis in South IndiaAnn Acad Med Singapore200635318518916625268

- AshayeAAimolaAKeratitis in children as seen in a tertiary hospital in AfricaJ Natl Med Assoc2008100438639018481476

- KunimotoDYSharmaSReddyMKMicrobial keratitis in childrenOphthalmolog y19981052252257

- HsiaoCHYeungLMaDHPediatric microbial keratitis in Taiwanese children: a review of hospital casesArch Ophthalmol2007125560360917502497

- Bella-HiagALEbana MvogoCTraumatologie oculo-orbitaire infantile à l’hôpital Laquintinie de Douala (Cameroun). [Ocular traumatism in children at Laquintinie Hospital, Douala (Cameroon)]Santé2000103173176 French11022147

- AshayeAOEye injuries in children and adolescents: a report of 205 casesJ Natl Med Assoc20091011515619245073

- PrajnaVNPillaiMRManimegalaiTKSrinivasanMUse of Traditional Eye Medicines by corneal ulcer patients presenting to a hospital in South IndiaIndian J Ophthalmol1999471151816130279

- Al-BdourMDAzabMAChildhood eye injuries in North JordanInt Ophthalmol199822526927310826542

- LawanACongenital eye and adnexial anomalies in Kano, a five year reviewNiger J Med2008171373918390130

- Chuka-OkosaCMMagulikeNOOnyekonwuGCCongenital eye anomalies in Enugu, South-Eastern NigeriaWest Afr J Med200524211211416092309