Abstract

Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy complicated with choroidal neovascularization is rare in children. We report three children from a Malay family of five siblings with Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy, in which two of them subsequently developed choroidal neovascularization. The possible pathogenesis of this rare condition is described and highlighted in this report.

Introduction

Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy with childhood onset causes a slowly progressive central visual impairment. It is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner in the majority of cases. Though choroidal neovascularization secondary to Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy is rare, it is known to cause childhood blindness if left untreated.Citation1 We report three brothers of a Malay family with Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy two of whom developed unilateral choroidal neovascularization. Rapid diagnosis and prompt treatment of this condition are essential to prevent significant visual loss in these children.

Case report

Case 1

The eldest child was referred to our clinic for bilateral hypermetropia by a private optometrist at the age of 9 years. His cycloplegic refraction was +7.00/−0.50 × 170 in the right eye and +7.75/−0.75 × 20 in the left eye. He was prescribed glasses that successfully corrected visual acuity to 6/6 in both eyes. Fundoscopic examination revealed localized elevated foveal lesions with yellowish deposit in both eyes, which were suggestive of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. The electrooculogram was abnormal, with Arden ratios of 1.1 in the right eye and 1.3 in the left eye. Family screening revealed that two of his younger brothers had similar fundoscopic findings.

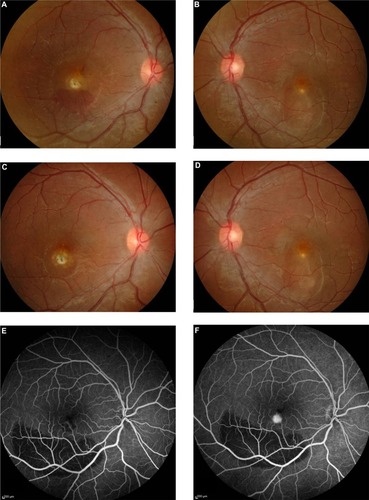

The patient’s visual acuity remained stable until the age of 18 years, when he complained of a sudden painless reduction in vision in the right eye, lasting 3 weeks. Visual acuity had deteriorated to 6/36 in the affected eye, while his left eye’s vision remained at 6/7.5. Fundoscopic examination revealed evidence of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy bilaterally, with a submacular hemorrhage in the right eye ( and ). Fundus fluorescein angiography of the right eye showed a net of increasing hyperfluorescence at the macula, consistent with a choroidal neovascularization ( and ). Optical coherence tomography of his right eye revealed subretinal reflection of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization with surrounding subretinal edema ().

Figure 1 (A–H) Case 1. Color fundus photograph of the right eye at presentation, showing submacular hemorrhage and a yellowish fibrotic nodule (A). Color fundus photograph of the left eye, showing a dome-shaped elevation at the foveal region with the presence of yellowish deposits (B). Fundoscopy of the right eye, showing resolved subretinal hemorrhage with residual scarring at the foveal region at 2 months posttreatment (C). Fundoscopy of the left eye, showing similar findings to those at presentation (D). Fundus fluorescein angiogram, showing increased hyperfluorescence at the macula, consistent with choroidal neovascularization (E early phase, F late phase). Optical coherence tomography of the right eye at presentation, showing a subretinal pigment epithelium fibrotic nodule with a subretinal reflection of a subfoveal choroidal neovascularization and surrounding subretinal fluid (G). Optical coherence tomography of the right eye at 2 months posttreatment, showing resolution of the subretinal fluid at the right macula (H). Green lines indicate the cross-section of the macula shown by the adjacent optical coherence tomography image.

The patient was treated with a single dose of intravitreal 1.0 mg ranibizumab under sub-Tenon’s local anesthesia. Two months later, his visual acuity improved to 6/12, and fundoscopic examination showed that the subretinal hemorrhage had resolved, with residual scarring at the subfoveal region in the affected eye ( and ). These findings were supported by optical coherence tomography imaging ().

He was last evaluated at 9 months posttreatment. His best-corrected visual acuity was 6/9 in the right eye and 6/7.5 in the left eye. Fundoscopic examination remained stable, with no evidence of recurrence in the right eye or new neovascularization in the left eye.

Case 2

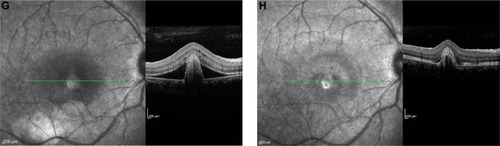

The third child was first examined at 4 years. He was asymptomatic. His best-corrected visual acuity was 6/6 in both eyes. Serial fundoscopy findings revealed signs of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. There were no signs of submacular hemorrhage to suggest the presence of choroidal neovascularization ( and ). Optical coherence tomography demonstrated minimal signs of subretinal fluid accumulation in both eyes ( and ).

Figure 2 (A–D) Case 2. Color fundus photograph of the right (A) and left (B) eyes showing dome-shaped elevation of the foveal regions, with the presence of yellowish deposits, signifying Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. Optical coherence tomography of the right (C) and left (D) eye revealed the presence of subretinal fluid at the foveal regions. Green lines indicate the cross-section of the macula shown by the adjacent optical coherence tomography image.

Case 3

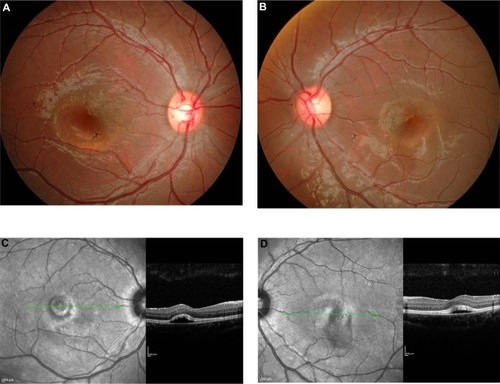

The fourth child was diagnosed with Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy at 4 years old after a family eye screening. At the age of 6 years, he developed a choroidal neovascularization in the right eye ( and ), and that was promptly managed.Citation2

Figure 3 (A–D) Case 3. Color fundus photographs of the fourth child at the time of diagnosis of choroidal neovascularization (A and B). Right fundoscopy at 3 years posttreatment, showing a resolved subfoveal hemorrhage with a residual dome-shaped elevation and yellowish deposits at the foveal region (C). Left fundoscopy at 3 years postpresentation, showing an increase in the size of the dome-shaped elevation, with no sign of a submacular hemorrhage (D).

Currently, his visual acuity is 6/6 in both eyes. Fundoscopic examination ( and ) remains stable in both eyes, 3 years after the intravitreal ranibizumab injection in the right eye. No systemic or ocular complications were observed throughout his follow-up.

Detailed clinical presentations of the aforementioned patients and their unaffected siblings are summarized in . There is no history of consanguinity. Fundoscopic examinations of the second and youngest siblings showed normal findings. Electrooculography was performed in the two older brothers, but was not performed in other siblings, because they were too young at the time of examination. Examination of the parents’ eyes was essentially normal, except for the fact that their mother had a hyperpigmented flat scar in her left macula. Genetic analysis was not performed due to financial constraints.

Table 1 Clinical summary

Discussion

Familial cases of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy have been described amongst the Spanish, Danish, Italian, French, American, and Chinese.Citation3–Citation7 Based on a PubMed literature search, the present study is the first report of familial Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy in individuals of Malay decent, and two of the described children had presented with active choroidal neovascularization.

Zhang et al performed a postmortem examination and described the histopathological findings in two eyes with clinical diagnosis of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. They reported a well-circumscribed area of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) hyperplasia, accumulation of lipofuscin in the RPE, deposition of granular material in the photoreceptors, macrophages, and drusen. They also observed an area in the region of a large sub-RPE drusen where Bruch’s membrane was not intact.Citation8

Interestingly, in an animal study, Julien et al found that zinc deficiency in the pigmented eyes of rats yielded an increased lipofuscin accumulation in the RPE, with decreased melanosomes in its microvilli and irregular thickness of Bruch’s membrane.Citation9 This condition may facilitate the penetration of macrophages from the choroid to the RPE.

RPE dysfunction in Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy causes the accumulation of subretinal fluid, which elevates the retinal layers away from the RPE, making the phagocytosis of the photoreceptor outer segment less likely to occur. The eventual phagocytosis of older photoreceptor outer segment loads the RPE with precursor for lipofuscin. The increased oxidative stress that leads to lipofuscinogenesis increases the amount of free radicals, which further damage the retinal architecture. This postulation probably explains the initiation of choroidal neovascularization formation in Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy.

Querques et al reported that bestrophin mutation did not correlate with disease severity.Citation10 Both the age of onset and disease progression were highly variable in patients with the same mutation. Therefore, the variability shown by these three Malay brothers regarding age of onset and disease progression could not be explained. It is difficult to deduce why choroidal neovascularization had developed in these two siblings but not in the other brother, who also showed clinical signs of Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. Interestingly, we observed that the two siblings who had developed choroidal neovascularization demonstrated larger areas of subretinal fluid accumulation and deposits compared to the sibling without choroidal neovascularization formation. We postulate that the severity of RPE dysfunction and an increase in oxidative stress play important roles in the formation of choroidal neovascularization.

Both of the patients responded well to the single dose of intravitreal ranibizumab. The eldest child showed stable visual acuity and fundoscopy findings 9 months after treatment, while the fourth child has not had any recurrence 3 years later. No recurrence or adverse events were noted throughout their follow-up visits. This observation is consistent with an observation by Ruiz-Moreno et al,Citation11 where they described an excellent outcome in a 3-year follow-up of a boy who was treated with a single injection of intravitreal ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy.

Conclusion

Choroidal neovascularization secondary to Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy is uncommon in the pediatric community. Two siblings with choroidal neovascularization is particularly unusual. Prompt diagnosis and management of this condition are vital to prevent blindness in these children. A single dose of intravitreal ranibizumab was effective in our patients, but this treatment requires long-term follow-up and monitoring.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeuJSchrageNFDegenringRFChoroidal neovascularisation secondary to Best’s disease in a 13-year-old boy treated by intravitreal bevacizumabGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol2007245111723172517605026

- HeidaryFHitamWHNgahNFGeorgeTMHashimHShatriahIIntravitreal ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization in Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy in a 6-year-old boyJ Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus201148 onlinee19e2221417187

- Piñeiro-GallegoTAlvarezMPereiroIClinical evaluation of two consanguineous families with homozygous mutations in BEST1Mol Vis2011171607161721738390

- SodiAMenchiniFManittoMPOcular phenotypes associated with biallelic mutations in BEST1 in Italian patientsMol Vis2011173078308722162627

- LacassagneEDhuezARigaudièreFPhenotypic variability in a French family with a novel mutation in the BEST1 gene causing multifocal best vitelliform macular dystrophyMol Vis20111730932221293734

- IannacconeAKerrNCKinnickTRCalzadaJIStoneEMAutosomal recessive Best vitelliform macular dystrophy: report of a family and management of early-onset neovascular complicationsArch Ophthalmol2011129221121721320969

- LiYWangGDongBA novel mutation of the VMD2 gene in a Chinese family with Best vitelliform macular dystrophyAnn Acad Med Singapore200635640841016865191

- ZhangQSmallKWGrossniklausHEClinicopathologic findings in Best vitelliform macular dystrophyGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol2011249574575121136072

- JulienSBiesemeierAKokkinouDEiblOSchraermeyerUZinc deficiency leads to lipofuscin accumulation in the retinal pigment epithelium of pigmented ratsPLoS One2011612e2924522216222

- QuerquesGZerbibJSantacroceRFunctional and clinical data of Best vitelliform macular dystrophy patients with mutations in the BEST1 geneMol Vis2009152960297220057903

- Ruiz-MorenoOCalvoPFerrándezBTorrónCLong-term outcomes of intravitreal ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to Best’s disease: 3-year follow-upActa Ophthalmol2012907e574e57522339886