Abstract

To the ancient Greeks, glaukos occasionally described diseased eyes, but more typically described healthy irides, which were glaucous (light blue, gray, or green). During the Hippocratic period, a pathologic glaukos pupil indicated a media opacity that was not dark. Although not emphasized by present-day ophthalmologists, the pupil in acute angle closure may appear somewhat green, as the mid-dilated pupil exposes the cataractous lens. The ancient Greeks would probably have described a (normal) green iris or (diseased) green pupil as glaukos. During the early Common Era, eye pain, a glaucous hue, pupil irregularities, and absence of light perception indicated a poor prognosis with couching. Galen associated the glaucous hue with a large, anterior, or hard crystalline lens. Medieval Arabic authors translated glaukos as zarqaa, which also commonly described light irides. Ibn Sina (otherwise known as Avicenna) wrote that the zarqaa hue could occur due to anterior prominence of the lens and could occur in an acquired manner. The disease defined by the glaucous pupil in antiquity is ultimately indeterminate, as the complete syndrome of acute angle closure was not described. Nonetheless, it is intriguing that the glaucous pupil connoted a poor prognosis, and came to be associated with a large, anterior, or hard crystalline lens.

Keywords:

Introduction

The early history of glaucoma contains a number of mysteries. To the ancient Greeks, glaucoma described the appearance of the pupil, but historians have debated whether the term meant blue, gray, green, or gleaming. Which color was seen in antiquity? What pathology produced this appearance? Glaucoma became defined in antiquity and the Middle Ages as a disorder of the crystalline lens. How did the term evolve to represent an optic neuropathy associated with ocular hypertension?

Angle closure

Given that glaucoma came to be defined in antiquity as a disease of the crystalline lens, we hypothesized that its early history might be related to angle closure. Today, it is understood that the lens causes angle closure by inducing pupillary block.Citation1 Angle closure is one of the more common causes of visual loss from glaucoma worldwide, and affects 0.4% of those with European ancestry over the age of 40 years, with higher prevalence rates in Asia.Citation2 Angle closure must have occurred in antiquity, and its dramatic presentation would likely have caught the attention of medical writers. We reviewed early descriptions of glaucoma for findings consistent with angle closure:Citation3 1) loss of vision; 2) a swollen lens, anteriorly located; 3) a dilated, fixed, or irregular iris; 4) incurability, or at least difficulty in cure (which today would be understood as an optic neuropathy secondary to ocular hypertension); or 5) a glaucous (light blue, gray, or green) pupil (glaukos, the Arabic word zarqaa).

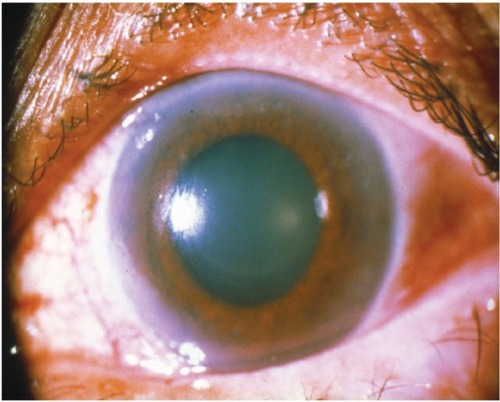

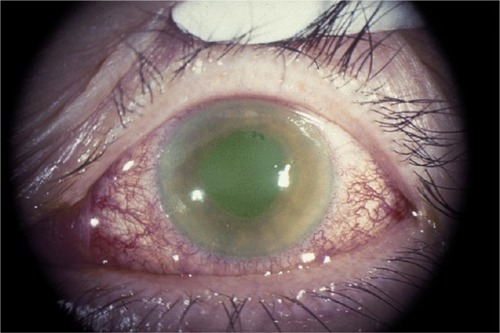

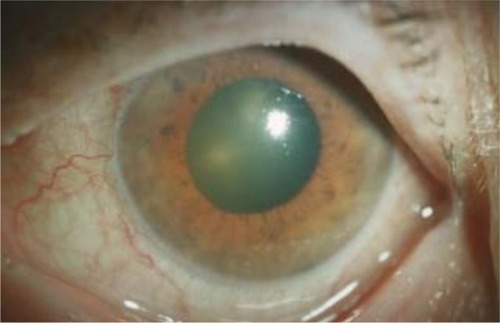

The last criterion, the presence of a glaucous pupillary hue, may surprise the reader. Examination of pupillary hue is simply not part of present-day ophthalmic training for the evaluation of angle closure. We have better tools, including ophthalmoscopy, slit lamp biomicroscopy, gonioscopy, and tonometry. But many early descriptions of glaucoma reported a greenish hue to the pupil. Historians have not agreed on the explanation for this green color. It has been suggested that examination with candle light was responsible.Citation4 An alternative explanation involves deposition of “blood pigments” in the lens epithelium following intraocular hemorrhage.Citation5 We propose that angle closure glaucoma might explain many cases of the green pupil, as seen in photographs of this disorder (–).Citation6–Citation11 The green color is seen due to the mid-dilated pupil exposing the cataractous lens. The lessening of the greenish hue with lowering of the intraocular pressureCitation7 suggests a contribution from other factors, such as corneal edema.

Figure 1 Acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Figure 2 Acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Figure 3 Acute angle closure glaucoma secondary to choroidal hemorrhage.

Figure 4 Acute angle closure attack due to malignant glaucoma in an eye with patent peripheral iridotomy.

The evolution of color terms

In antiquity, glaucoma was defined by the pupillary hue called glaukos. Could glaukos describe green objects? Studies on the evolution of color terms in language offer useful insights. Hugo Magnus, a 19th Century German ophthalmologist, provided missionaries, colonial officials, and other travelers with standardized color chips and a questionnaire to learn the color names used by 61 indigenous peoples from every inhabited continent.Citation12 Magnus concluded in 1880:

Linguistic expressions for long wave colors are always much more sharply defined than those for short wave colors … The most usual mixing is that of green with blue … it often occurs that the colors of shorter wavelength are united with the linguistic concept of dark or indefinite. Blue and violet (and even green) are designated black or grey.Citation12

Berlin and Kay have noted that “there appears to be a fixed sequence of evolutionary stages through which a language must pass as its basic color vocabulary increases”,Citation12 In general, terms for white, black, and red precede the introduction of terms for (and distinction of) green, yellow, and blue.Citation12 According to some scholars of English, blue was used more expansively and encroached upon its spectral neighbors violet and green until the 18th Century.Citation13 Thus, it is reasonable to suspect that the ancient Greek term glaukos might have encompassed blue, gray, and green.

Application of color terms to the eye

Moreover, existing color terms were not always applied to the eye. For example, we reviewed every use of the term “eye(s)” in the King James translation of the Bible, first completed in 1611.Citation14 We conclude that this translation reflects the most advanced stage of color language evolution, according to the system of Berlin and Kay.Citation12 Nonetheless, throughout the text, eyes are described as bright or dark without mentioning specific hues (eg, Zechariah 11:17, Matthew 6:22, 1 Corinthians 15:52).Citation14

In present-day English books, when an eye color is described, the color is specified as green about 12% of the time.Citation15 Thus, the present-day reader might find it implausible that a culture could fail to agree that an eye color resembles the color of green leafy plants. But this comparison appears to be a relatively recent event in English as well. Using computerized searches, we previously reported that eyes were not typically described as green or brown before 1840.Citation15 English speakers were generally content to describe eyes as “bright” or “blue”, or else “dark” or “black”. Of course, Shakespeare wrote of “greene-eyed ielousie” in The Merchant of Venice and of “the greene eyd monster” when describing jealousy in Othello.Citation16 Despite these metaphors, it was unusual for the early 19th century writers to describe eye color as literally green. For example, in 1822, the reviewer of a novel which described a dwarf as having “large, green, goggle eyes”, noted,

… we endeavoured, for some moments, to conceive what like a green eye might be; and we had almost decided that the author had given this colour to the Dwarf’s eyes, merely to distinguish them from the eyes of all other mortals.Citation17

Similarly, the Greeks had terms for the color of green plants, such as χλωρός (kloros),Citation13,Citation18–Citation20 used by Homer.Citation12 In addition, prasinos, the color of the leek, was used by AristotleCitation19,Citation21 and is the present-day Greek term for green. Yet our review of hundreds of ancient color descriptions shows that the Greeks did not describe eyes as prasinos or kloros.Citation13,Citation18,Citation20–Citation24 With respect to an eye disease affecting the elderly, the Greeks might have had a logical reason to avoid using the term kloros. They strongly associated old age and disease with dryness, and youth and vitality with moisture.Citation20 Kloros, the color of lush vegetation, represented moisture and therefore, youth.Citation20 Similarly, in Latin, viridis for the green of vegetation,Citation18,Citation19,Citation23 was not used to describe eye color.

The ancient Greek author describing a green eye would likely use the term glaukos. The primary alternative would be “glassy”. Indeed, the eye and its structures were occasionally compared with the color of glass. The vitreous humor (hyaloides in Greek) is so named because it was thought to resemble glass. Nonetheless, the Latin vitreus, as a general color term, is typically interpreted as a greenish hue.Citation18,Citation23 The reason is that ancient or Roman glass was often green, due to contamination by iron.Citation21 Sometimes, glass was blue-green,Citation18 blue, amber, or other colors, depending on contaminants and additives. The glaucous and glassy hues overlapped. In the 1st Century AD, a glass bottle was described as γλαυκῆς (glaukes).Citation21 Apsyrtos of Bithynia (fl 3rd Century AD), wrote (Apud Hippiatrica Berolinensia 11.1),

When γλαύκωμα [glaucoma] occurs, lancing is useless because [the disease] is incurable. It is a result of a so-called glazing of the eye (ύάλωμα, [hyaloma, glassy disease]) rather like a λευκη [leuke] pebble.Citation21

Nonetheless, comparison of eye appearance with glass was infrequent.

Objects described as glaukos

In summary, glaukos might have included green and might have been applied to the eyes, despite the availability of other green color terms. But what do we learn from a direct analysis of the term glaukos? In the Iliad, Homer (fl 7th or 8th Century BC) repeatedly described the goddess Athena as γλαυκῶπις (glaukopis), and described the sea as γλαυκή (glauke).Citation21 Maxwell-Stuart has prepared a 254-page compendium of hundreds of uses of glaukos and related terms by 120 Greek authors between Homer and the 5th Century of the Common Era.Citation21 We quantitatively analyzed these uses (). In short, the best translation for glaukos during this period might be “the color of eyes which are not dark”. Almost 80% of prose authors used glaukos and related terms to describe eye color.

Table 1 Number of authors using γλαυκός (glaukos) or related terms, by type of object describedTable Footnote*

Glaukos continued to be used to describe the sea, particularly in verse (). Whether the term originated in pre-Homeric times with the sea or with eye color is a matter of conjecture. Its predominant use to describe eye color in prose suggests that, like the color term “hazel” in English, glaukos would evoke imagery of the eye. Only about 20% of prose authors used glaukos or related terms to represent diseased eyes. Thus, the term usually described the color of a healthy eye. As it is not always clear if descriptions of animals as glaukos relate to the coat or to the eyes (), the association with the eyes may be even stronger. Only two authors (2%) used the term to describe the owlCitation21 ().

Aristotle is commonly understood to have written of transformation of the infant’s eyes from “blue” to a darker color with time. In fact, he described infant eyes as γλαυκότερα (glaukotera) and γλαυκά (glauka). Given that when a newborn’s eyes do transform to a darker color, they usually start as blue or light gray, we might surmise that glaukos could represent these hues. We also can surmise that glaukos eyes were light colored by their repeated association with visitors from a Northern climate, with blond (xanthos) or reddish hair, and with a pale complexion.Citation21 Many authors, such as Hirschberg and Maxwell-Stuart,Citation21 wrote that glaukos represented light blue exclusively. Indeed, glaukos described blue objects on occasion: woad dye, lapis lazuli, and topaz.Citation21

On the other hand, other uses of glaukos suggest the color green. Plants were described as glaukos by about one-sixth of the ancient authorsCitation21 (). Usually, the term applied to the olive leaf or branch, but also to the greater celandine or perhaps the horned poppy (Glaucium flavum), the laurel, the elder, and grapes.Citation21 Of course, such usage might be interpreted as a gray or blue-gray cast, but one cannot ignore the fact that the predominant hue of leafy vegetation is green. Moreover, glaukos described a glass bottle, snakes, and several green gems: iaspis (jasper), beryl, and emerald.Citation21 And, of course, even the Mediterranean Sea may have an aqua cast in the shallows. In summary, if an eye had appeared green in antiquity, in a healthy or diseased state, glaukos is at least a plausible descriptor.

Some have suggested that glaukos in the period of Homer suggested merely a brightness,Citation13 such as glaring,Citation18 with an implication regarding hue coming closer to the meaning implied in the Common Era.Citation13,Citation18 However, our analysis of color terminology shows no shift in usage with the Common Era, once one separates prose from verse (see Supplementary material. Moreover, although a specific range of hues was encompassed by glaukos, the term was not applied to hues indiscriminately. For instance, red objects were not described as glaukos. Of course, these data cannot provide insight into the origin of the term glaukos during pre-Homeric times, whether in relation to the sea or to the eye.Citation21

The glaucous eye in the Hippocratic era

During the era of Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 370 BC), the lens was not described, and couching was not reported in Greece. However, the color of the eye was held to portend prognostic significance. Hippocrates wrote (Prorrheticon 2.20-Littré 9.48): “Pupils which have become γλαυκοúμεναι [glaukoumenai] or ἀργυροειδέες [argyroeidees, silvery] or κυἀνεαι [kyaneai (the cognate of cyan)] are useless”.Citation21,Citation25 Hippocrates referred to glaukosis as a disease of the elderly (Aphorisms III.31.6): “To olde men doth happen… moistnesse and humidities of the bellie, eyes, and nostrills, dimnesse of the sight, Glaucoma [γλαúκωσις], and dulnesse of hearing.

The philosopher Aristotle (383-322 BC) discussed eye color in De Generatione Animalium (779a.26 to 780b.2-3). He categorized eye color as follows:

The eyes of human beings show great variety of colour; some are γλαυκοί [glaukoi] some χαροποί [charopoi, amber], some μελανόφθαλμοι [melanopthalmoi, dark], others αἰγωποί [aigopoi, goat-eyed, yellow]Citation21,Citation27,Citation28

The eye color was determined by the amount of water in the eye, in the same way that a shallow body of water appears bright, while a deep sea appears dark:

Clear (εὐδιόπτον, [eudiopton]) sea-water appears γλαυκόν [glaukon], that which is less clear, murky (ὑδατωδες, [hydatodes]), and that through which one cannot see clearly because of its depth, μέλαν [melan] and κυανοειδές [kyanoeides].Citation21

Aristotle observed: “The eyes of all infants are γλαυκότερα [glaukotera] immediately after they are born”.Citation21 He hypothesized that the small eye could hold little water: “In children, it is because of the small volume of fluid [that the eyes] appear γλαυκά [glauka] at first”.Citation21 A pathologic change in color to glaukos in the elderly was also accounted for by a shortage of moisture in the eye: “γλαύκωμα [glaukoma] tends to attack those with γλαυκοῖς [glaukois] eyes … γλαύκωμα is a kind of dryness of the eyes”.Citation21,Citation25

In general, glaukos in this era likely represented a light-colored media opacity. Aristotle’s emphasis on inadequate depth of water within the eye could suggest intraocular pathology, such as cataract. A subsequent observer from the era of couching, Rufus of Ephesus, stated that what the ancients called glaukosis was simply hypochyma, defined as the structure displaced by couching. There is no reason to question this assessment, in general, although corneal edema or opacities could have been described on occasion.

The glaucous eye in the period of couching

Couching was apparently known in the Greek world in the 3rd Century BC, when Chrysippus mentioned the surgery.Citation29 But in the Common Era, there are complete descriptions of couching, and of the crystalline lens. Couching was thought to remove a thickened substance which had settled in front of the crystalline lens. The Romans called this substance suffusio, the Greeks called it hypochyma, and later authors in Arabic called it ma’ (water).

Notably, the glaucous color was associated with a poor result from couching, and gradually evolved to be ascribed not with hypochyma, but with pathology of the crystalline humor. Theories of eye color related to the vitreous, the lens, or the iris. The first complete description of couching, along with a discussion of the crystalline lens, came from the Roman encyclopedist Cornelius Celsus (c 25 BC–50 AD), in De Medicina (VII.7.13-14). Eye color derived from the glass-like vitreous:

Contained in that hollow is what, from its resemblance to glass [vitri], the Greeks call hyaloides; it is humour, neither fluid nor thick, but as it were curdled, and upon its colour is dependent the colour of the pupil, whether black [niger] or steel-blue [caesius].Citation30

Indeed, many of the colors of Roman glass (green, blue, amber) do resemble various shades of iris color.

The word caesius, describing a light-colored eye, usually in people,Citation18 was often the Latin translation of glaukos,Citation18,Citation19,Citation21 and in fact, was used to describe the goddess Minerva,Citation31,Citation32 the Roman counterpart to Athena. Caesius eyes have been described in translation as blue,Citation19,Citation24 gray, and occasionally green.Citation24

Celsus also described couching, which he believed displaced a pathologic fluid (suffusio), which had hardened anterior to the crystalline humor. Celsus believed the crystalline humor was the seat of vision, ie, the essential receptive organ.Citation30 He described factors which predicted the outcome of couching:

… a humour forms underneath the two tunics … and this as it gradually hardens [indurescens] is an obstacle to the visual power within. And there are several species of this lesion; some curable, some which do not admit of treatment. For there is hope if the cataract [suffusio] is small, … if it has also the colour of sea water [marinae aquae] or of glistening steel [ferri nitentis], and if at the side there persists some sensation to a flash of light. If large, if the black part of the eye has lost its natural configuration and is changed to another form, if the colour of the suffusion is sky blue [caeruleus] or golden [auri] … then it is scarcely ever to be remedied. Generally too the case is worse when the cataract has arisen … from severe pains in the head … And in the cataract itself, there is a certain development. Therefore we must wait until it is no longer fluid, but appears to have coalesced to some sort of hardness [duritie].Citation30

In present-day English, cerulean denotes exclusively a shade of blue, but the ancient caeruleus resembled glaukos in spectral range. Caeruleus was generally a blue or gray hue,Citation19,Citation31,Citation32 and was used to describe eyesCitation31,Citation32 or the sea.Citation18,Citation23,Citation31,Citation32 Caeruleus could also describe green objects,Citation18,Citation19,Citation31,Citation32 such as plants.Citation16,Citation18 Compared with glaukos, caeruleus often implied a darker hue due to its association with deeper water.Citation18,Citation19,Citation31,Citation32 On the other hand, caeruleus was used to describe the lighter eyes of the Germans.Citation19,Citation24 Like glaukos eyes in Greece, the lighter eyes of Northern Europeans with caeruleus eyes might have negative connotations in Rome, as barbaric or uncivilized.Citation19 In Celsus, then, we have the suggestion that no light perception (optic neuropathy), an irregular pupil, a glaucous-like hue, and pain are poor prognostic indicators, but these are presented as isolated findings, rather than as part of a complete syndrome.

Demosthenes Philalethes (early 1st Century AD) wrote an influential work, Ophthalmicus, portions of which survived through subsequent authors, such as Aetius of Amida (Apud Aetium: Libri Medicinales 7.52).Citation33,Citation34 In Demosthenes’ work, some glaucoma is attributed to pathology of the crystalline humor.

The name glaucoma [γλαύκωσις, glaukosis] is employed in two senses. Glaucoma [Γλαύκοσις] proper is a coloration of the crystalline humor to a sea-blue [γλαυκόν, glaukon], together with a drying and hardening [πῆξις, pexis] of that structure. The other kind of glaucoma [γλαυκῶσεως, glaukoseos] arises from cataract [ύποχύματος, hypochymatos] formation, the exudation becoming hardest and most dry in the pupil. This latter kind is incurable.Citation35

To the ancient Mediterranean authors, a pupil the color of the sea (eg, marinae aquae of Celsus, or θαλαςςίζει [thalassizei] of Demosthenes) represented a favorable prognosisCitation33–Citation35 and probably implied a blue color.

Next, we see in the writings of Rufus of Ephesus (80-150 AD) that glaucoma has become firmly associated with the crystalline lens (Fragmenta 116): “…γλαυκώματα [glaukomata] are changes in the crystalline fluid altering under the influence of moisture to γλαυκόν [glaukon] … All γλαυκώματα are incurable”.Citation21 Glaucous was also one of the standard eye colors, which was due to the iris (Nomina Corporis, 25): “In accordance with the colour of the iris [Ιριν], one says that [the eye] is μέλανα [melana, black], πυρρὸν [pyrron, flame-colored, russet], γλαυκόν [glaukon] or χαροπον [charopon, amber]”.Citation21 Rufus’ image of a rainbow (Ιριν) is the origin of the present-day anatomical term iris.Citation36

Galen of Pergamon (c 129–199 AD) was one of the most prolific and influential ancient medical authors. His theory of eye colors was similar to that of Aristotle, in that a lesser amount of fluid in the eye resulted in a brighter hue (glaukos), while more fluid would be darker, just as is deep water. Galen added that the crystalline humor, unknown in Aristotle’s time, was itself a light source, and the glaukos hue was more likely if the crystalline was thicker, anteriorly located, or hard. This could be seen in the corneal reflection, which Galen believed to emanate from the crystalline humor. Galen wrote in Ars Medica (section 9, K1.330) a passage also recorded by Oribasius:Citation21,Citation38

As far as the color [χρόαν, chroan] of the eye is concerned we have to differentiate the following: The eye will appear blue [γλαυκòς, glaukos] either because of the size and the brightness of the crystalline lens or because the lens is located more anteriorly; similarly it can be due to not enough or not pure enough watery fluid in the pupil. If all these conditions are fulfilled the eye will appear in a saturated blue [γλαυκότατος, glaukotatos]. If some of the conditions are present but others not then the eye will demonstrate variations of blue [γλαυκότητι, glaukoteti]. A black [Μέλας, melas] eye has either a small crystalline lens or the lens is deeply located or has incomplete brightness; it can also be due to an ample amount of aqueous fluid or because the fluid is not pure.Citation39

In the same passage, Galen wrote that the crystalline humor contributes to the dryness of the eye if the crystalline is too hard (σκληρότερον, scleroteron) or exceeds the amount of thin liquid (aqueous).Citation38

It is not clear that this theory explaining light-colored eyes necessarily implies a pathologic change (though that may have been intended in some instances). Elsewhere, Galen noted that the glaucous hue could be a pathologic change:

Damage to the eyes occurs when too much fluid is drawn off during couching for cataracts, and the symptom called by doctors γλαύκωσις [glaukosis] is a dryness and disproportionate coagulation [πῆξις, pexis] of crystalline fluid.Citation21,Citation40

In summary, the period of couching sees a progression of the unfavorable glaucous hue moving posteriorly to be firmly associated with the crystalline humor. In Galen’s writings, the glaucous hue is associated both with a larger, anterior, and hard crystalline humor and, elsewhere, with damage to the eyes. Celsus had noted a glaucous hue, optic neuropathy, pain, or pupil irregularities as poor prognostic indicators. Although a comprehensive description of the syndrome is lacking, it is intriguing that the glaucous hue was repeatedly described as implying a more severe type of pathology and came to be associated with the crystalline humor.

Medieval works in Arabic

During the Middle Ages, the ancient concept of glaucoma was translated into Arabic works, which were subsequently translated into Latin several centuries later. Five early authors who wrote in Arabic played important roles. Three were Christians who practiced in Baghdad:

Yuhanna ibn Masawaih (777–857 AD), known to later Latin writers as Mesue;Citation41

Hunain Ibn Ishaq (809–877 AD), originally of Southern MesopotamiaCitation42 and known later as Johannitus, who was the student of Masawaih but eventually eclipsed him in influence. Hunain systematically translated the ophthalmic works of Galen and other classical authors into Arabic, and Hunain’s ophthalmic treatise was widely cited;

Ali ibn Isa el-Kahhal (c 940–1010 AD),Citation43 a dedicated oculist, known later as Jesu Hali,Citation44 who cited Hunain.Citation43,Citation45 Two additional authors in Arabic were Persian:

Abul Hasan Ahmad ibn Muhammad Tabari (c 916–986 AD) was a physician who treated eye diseasesCitation46 and covered ophthalmology in his work Al-Mu’alajat al-Buqratiya (The Hippocratic Treatments).Citation44 Tabari mentioned “migraine of the eye” (Shaqiqat Al-Ayn),Citation44 which according to later Arabic works involved eye pain, a pressure sensation, opacification of the ocular fluids, and a dilated pupil.Citation44 However, we are not aware of direct continuity between these teachings and later European teachings.

Abu Ali al-Husain Ibn Sina (c 980–1037 AD), known later as Avicenna, was a polymath who wrote 459 treatises, including The Canon of Medicine, a comprehensive encyclopedia.

These authors, beginning with Mesue and Hunain, translated γλαυκός (glaukos) as zarqaa in both pathologic casesCitation41–Citation45,Citation47 and when the term was used to represent light-colored irides.Citation42,Citation43,Citation47 The two terms had many parallels. Like glaukos, zarqaa was used primarily to describe eyes, particularly those with light-colored irides.Citation48,Citation49 Moreover, as light-colored irides were less common than dark for both Greeks and Arabs, relative to foreign populations, both terms acquired negative moral connotations.Citation13,Citation21,Citation48,Citation49 Indeed, the zarqaa hue was used to describe the eyes of nonbelievers in The Holy Quran (Surah Ta-ha 20:102),Citation48,Citation49 which predated the works of Mesue and Hunain.

Like glaukos, zarqaa probably corresponded with a range of hues, as these Arabic authors sorted eye color into just three categories: zarqaa, gray (shahlaa), and black (sawdaa).Citation42–Citation44,Citation47,Citation50 zarqaa has been used to describe eyes which are blue or gray,Citation49 and occasionally green.Citation51 An oculist such as Ibn Isa might have observed a greenish hue in angle closure, but accepted the term zarqaa, due to the broad range of hues denoted. In these works, zarqaa does not seem to be used as the general term for blue. The color of the sky was described literally as “the color of the sky” (luwn al-samaa).Citation42–Citation44 Today, zarqaa has evolved to become the basic Arabic term for blue, and so glaucoma is colloquially referred to as “the blue water” (al-miyaah al-zarqaa) or simply “blueness”.

The Arabic authors agreed the zarqaa hue could occur with anterior pathology, which could be displaced by couching.Citation42–Citation44,Citation47,Citation52 Ibn Isa also noted a blue eye (zurqa) from forward dislocation (which did not impair the sight), or from drying, thickening, and coagulation of the humor (which did affect vision, and was difficult to cure).Citation43 Tabari and Ibn Sina (Avicenna) stated that the zarqaa hue could be associated with anterior prominence of the lens and could occur in an acquired (pathologic) manner.Citation44,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52

The Arabic works contain unambiguous comparisons of eye color, at least in a diseased state, to the color of green plants (akhdar).Citation53 Specifically, cataracts were described as green (akhdar).Citation42–Citation44,Citation47,Citation52 Avicenna recorded that green (akhdar), yellow, gypsum, and black cataracts did not improve with couching.Citation50

Solidification of intraocular fluids and palpation of the eye

Both hypochyma (suffusio, ma’) and glaucoma were thought to be due to a hardening or thickening of an intraocular humor (liquid). This process of hardening of the hypochyma was described by the Greeks as πῆξις (pexis).Citation25 In its first sense, pexis refers to “a fixing, fastening, joining, cementing”,Citation54 and is the root of the suffix pexy, as in “retinal cryopexy”.Citation16 Here, pexis is used in its second sense as “coagulation, curdling, congelation, hardening”.Citation54

Celsus stated that couching should not be performed until the suffusio had matured, or become adequately hard (duritie). He did not specify how this hardening would be checked. Later, Ibn Isa (Jesu Hali) made explicit that determination of cataract maturity required palpation of the eye.

Press his eyelid with your thumb … then open the eye and note the position of the cataract. In case it is not sufficiently matured or consolidated there will seem to be variations in its apparent breath and shape.Citation43,Citation45

Although not previously emphasized by historians, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) came to the opposite conclusion as Ibn Isa (Jesu Hali): the cataracts which were immobile during palpation due to hardening were less suitable for surgery.Citation47,Citation50,Citation52 Nonetheless, these authors agreed that one could evaluate the hardness of an intraocular humor by examination of its movement during ocular palpation.

Glaucoma, in the writings of Demosthenes and Galen,Citation30 was also believed to involve hardening (pexis), in this case of the crystalline humor. Galen also used the term σκληρότερον (scleroteron) to describe the hardening of the crystalline. Perhaps by analogy with hypochyma (suffusio, ma’), it was inevitable that palpation of the eye would eventually be proposed for the evaluation of glaucoma. However, this development does not appear to have occurred until the 18th Century.

Conclusion

Descriptions of glaucoma from antiquity through the early Middle Ages suggest certain aspects consistent with angle closure. Although not emphasized by present-day ophthalmologists, angle closure often produces a greenish hue to the pupil, due to the mid-dilated pupil and prominent cataractous lens. To the Greeks, the term glaukos was most commonly used to describe healthy, light-colored irides, but was used to a lesser extent to describe pathologic ophthalmic states. If either a healthy iris or a diseased pupil had appeared green, the term glaukos would likely have been used. During the period of Hippocrates, the description of a diseased eye as glaukos indicated a media opacity that was not dark. During the early Common Era, when couching was performed in Mediterranean Europe, descriptions of glaucous eye disease evolved. Celsus noted optic neuropathy, pain, a glaucous-like hue, and pupil irregularities as poor prognostic indicators, but not as part of an integrated syndrome. Galen noted the glaucous hue being associated with a prominent, anterior, or hard crystalline humor, and elsewhere, with vision loss. The Arabic authors translated glaukos as zarqaa, which also was commonly used to signify the color of irides that were not dark. Both the lesion displaced by couching and glaucoma were believed to result from the hardening of an intraocular humor (liquid). As the former was evaluated by ocular palpation, it is perhaps logical that glaucoma would eventually be evaluated in a similar manner.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Center Core Grant P30EY014801 and the Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant to the University of Miami.

Disclosure

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article. Further, the authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NongpiurMEKuJYAungTAngle closure glaucoma: a mechanistic reviewCurr Opin Ophthalmol20112229610121252671

- DayACBaioGGazzardGThe prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in European derived populations: a systematic reviewBr J Ophthalmol20129691162116722653314

- PatelKPatelSAngle-closure glaucomaDisease-a-Month201460625426224906670

- SnyderCMr Mackenzie investigates green cataractsArch Ophthalmol196574113313614306559

- DrewsRCGreen cataractArch Ophthalmol2006124457958616606889

- BartonKSecondary GlaucomaSpaltonDJHitchingsRAHunterPAAtlas of Clinical Ophthalmology3rd edPhiladelphiaElsevier Mosby2005225

- BaxterJMAlexanderPMaharajanVSBilateral, acute angle-closure glaucoma associated with Guillain-Barre syndrome variantBMJ Case Rep Epub2010721

- WilenskyJTCampbellDGPrimary Angle-Closure GlaucomaAlbertDMJakobiecFAPrinciples and Practice of Ophthalmology2nd edPhiladelphiaWB Saunders Company20002691

- Pierre Filho PdeTCarvalho FilhoJPPierreETBilateral acute angle closure glaucoma in a patient with dengue fever: case reportArq Bras Oftalmol200871226526818516431

- SeeJPhacoemulsification in angle closure glaucomaJ Curr Glaucoma Practice2009312835

- SpadoniVS1PizzolMMMunizCHMelamedJFortes FilhoJBBilateral angle-closure glaucoma induced by trimetoprim and sulfamethoxazole combination: case reportArq Bras Oftalmol2007703517520 Portuguese17768563

- BerlinBKayPBasic Color Terms: Their Universality and EvolutionBerkeleyUniversity of California Press19914145

- ClelandLStearsKColour in the Ancient Mediterranean WorldOxfordHadrian Books200440139

- The Holy Bible, King James version: containing the Old and New Testaments [webpage on the Internet]New YorkAmerican Bible Society1999 Available from: www.bartleby.com/108/Accessed September 5, 2014

- LefflerCTSchwartzSGStackhouseRByrd DavenportBSpetzlerKEvolution and impact of eye and vision terms in written EnglishJAMA Ophthalmol2013131121625163124337558

- Oxford English Dictionary Online [webpage on the Internet]OxfordOxford University Press2014 Available from: http://www.oed.com/Accessed September 5, 2014

- HibbertSA description of the Shetland IslandsThe Scots MagazineEdinburgh182289307

- ClarkeJImagery of Colour and Shining in Catullus, Propertius, and HoraceNew YorkPeter Lang200347274

- BradleyMColour and Meaning in Ancient RomeNew YorkCambridge University Press20097231

- IrwinEColour Terms in Greek PoetryTorontoHakkert19743178

- Maxwell-StuartPGStudies in Greek Colour Terminology. Vol. 1. GlaukosLeidenBrill Archive198126165

- Maxwell-StuartPGStudies in Greek Colour Terminology. Vol. 2. CharoposLeidenBrill Archive1981

- EdgeworthRJThe Colors of the AeneidNew YorkPeter Lang1992107162

- EvansECPhysiognomics in the Ancient WorldTrans Am Phil Soc196959Part 53648

- MagnusHWaughRLOphthalmology of the Ancients Part 1OostendeJ P Wayenborgh199895185

- HippocratesThe Whole Aphorismes of Great HippocratesLondonH L for Richard Redmer16105152

- Aristotle [webpage on the Internet]On the Generation of Animals. The Treatises of AristotleTaylorTLondonRobert Wilks1808423 Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=dOU-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA423&lpg=PA423&dq=aristotle+generation+of+animals+glaucoma&source=bl&ots=uvqTfHSRbG&sig=4WOVuu7bGKcg674ImSL65jCL7sQ&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FEp5U5LMAvDMsQS894GgCQ&ved=0CEsQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=glaucoma&f=falseAccessed September 5, 2014

- Aristotle [Webpage on the Internet]Generation of AnimalsPeckALCambridgeHarvard University Press1943492495 Available from: https://archive.org/stream/generationofanim00arisuoft#page/n3/mode/2upAccessed September 5, 2014

- Simplicius of CiliciaSimplicius: On Aristotle’s Categories 9–15GaskinRIthacaCornell University Press2000143

- CelsusCDe Medicina3SpencerWGLondonWilliam Heinemann Ltd1938346350 Pages available from: https://archive.org/stream/demedicina03celsuoft#page/348/mode/2upAccessed September 5, 2014

- LewisCTAn Elementary Latin DictionaryNew YorkAmerican Book Company1915

- RiddleJEA Complete English–Latin and Latin–English DictionaryLondonLongmans Green, and Co187076 Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=l_UsAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA76&dq=caeruleus+intitle:dictionary+intitle:latin&hl=en&sa=X&ei=pouwU_XHCuTlsATSzIKYAw&ved=0CEkQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=caeruleus%20intitle%3Adictionary%20intitle%3Alatin&f=falseAccessed September 5, 2014

- Aetius of AmidaThe Ophthalmology of Aetius of AmidaHirschbergJWaughRLBelgiumWayenborgh20008485

- AmidenusALibri Medicinales V–VIIIOlivieriABerlin1950308 Available from: http://cmg.bbaw.de/epubl/online/cmg_08_02.htmlAccessed September 5, 2014

- ShastidTHHistory of ophthalmologyAmerican Dictionary and Encyclopedia of OphthalmologyChicagoCleveland Press19138669

- Rufus d’ÉphèseOeuvres de Rufus d’ÉphèseParisImprimerie Nationale1879 Available from: http://www2.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/livanc/index.las?cote=36058&p=194&do=pageAccessed September 5, 2014 French

- AutenriethGKeepRA Homeric Dictionary for Use in Schools and CollegesNew YorkHarper1889160

- OribasiusOeuvres d’Oribase Translated by Bussemaker and Daremberg3Paris1858198200 Available from: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k28927t/f230.imageAccessed September 5, 2014 French

- HirschbergJBlodiFCThe History of Ophthalmology. Volume 1. AntiquityBonnVerlag J P Wayenborgh1982313314

- GalenCDe Usu Partium Libri XVII2LipsiaeIn aedibus B G Teubneri1907–1909 Available from: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924064990140;view=1up;seq=86Accessed September 5, 2014

- PrüferCMeyerhofMDie Augenheilkunde des Jûḥannā b Mâsawaih (777–857 n Chr)SezginFYuhanna Ibn Masawayh (d 243/857) Texts and StudiesFrankfurtGoethe University1996217268

- Is-Haq (Johannitus)Hunain IbnThe Book of the Ten Treatises on the Eye Ascribed to Hunain Ibn Is-Haq (809–877 AD)MeyerhofMCairoGovernment Press1928xvii141

- al-Kahhal (Jesu Hali)Ibn IsaMemorandum Book of a Tenth-Century OculistWoodCAChicagoNorthwestern University1936xxviii179

- HirschbergJBlodiFCThe History of OphthalmologyVol 2 The Middle Ages. The Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturiesBonnJ. P. Wayenborgh Verlag198553188

- al-Kahhal (Jesu Hali)Ibn IsaTadhkiratu’l Kahhalinal-SharafiMohiuddinHyderabadOsmania University196410260

- GhaffariFNaseriMAsghariMNaseriVAbul- Hasan al-Tabari: a review of his views and worksArch Iran Med201417429930124724609

- Ibn SinaAA (Avicenna)Die Augenheilkunde des Ibn SinaHirschbergJLippertJLeipzigVerlag von Veit Available from: https://archive.org/details/dieaugenheilkund00avicAccessed September 5, 2014 German

- Sulaymān ibn ‘Umar Jamal, Abū al-Baqā’ ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn ‘Akbarī. al-Futūḥāt al-Ilāhiīyah bi-tawḍīḥ tafsīr al-jalālayn lil- daqā’iq al-khafīyah. Wa-bi-al-hāmish kitābān: Tafsīr al-jalālayn lil- Suyūṭī wa-al-Maḥallī wa-imlā’ mā-manna bihi al-Raḥmān min wujūh al-i‘rāb wa-al-qirā’āt fī jamī‘ al-Qur’ān lil-‘Akbarī3CairoMiṣr Maṭba‘at al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī1960 Available from: https://archive.org/details/hashiya_jamal_amira_01Accessed September 5, 2014

- OmarAMDictionary of the Holy Qur’ânHockessinNoor Foundation International2010231 Available from: http://islamusa.org/dictionary.pdfAccessed September 5, 2014

- Ibn SinaAA (Avicenna)al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibbNew DelhiInstitute of History of Medicine and Medical Research1982175212

- LaneEWAn Arabic-English Lexicon. Part 1BeirutLibrairie du Liban196812271228 Available from: http://www.tyndalearchive.com/tabs/lane/Accessed September 5, 2014

- Ibn SinaAA (Avicenna)GerardusCAvicennae Arabum Medicorum Principis, Canon MedicinæVeniceFabium Paulinum1608 Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=qA4VK-w7WDoC&pg=PA551&lpg=PA551&dq=%22viriditate+oculi%22&source=bl&ots=8bmyuHM_9G&sig=_fJTiGj29u-GKIFYTtd6CfrLan0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=tXt7U_CRCsWBqgbAuYHoCw&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22viriditate%22&f=falseAccessed September 5, 2014

- Al-Haytham (Alhazen)IbnThe Optics of Ibn Al-Haytham Books I-III On Direct Vision II Introduction, Commentary, Glossaries, Concordance, IndicesSabraAILondonWarburg Institute, University of London198941

- GrovesJA Greek and English Dictionary: Comprising All the Words in the Writings of the Most Popular Greek Authors; With the Difficult Inflections in Them and in the Septuagint and New TestamentBostonJH Wilkins and RB Carter1842 Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=fesNAAAAIAAJ&pg=RA1-PA14&dq=%CF%80%E1%BF%86%CE%BE%CE%B9%CF%82+intitle:dictionary&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Eoh4U8X3JpC2sASShYCICg&ved=0CEIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=fastening&f=falseAccessed September 5, 2014

- SchloteTFreudenthalerNGeliskenFAkutes Winkelblockglaukom nach massiver intraokularer Blutung bei exsudativer altersbedingter Makuladegeneration unter gerinnungshemmender Therapie [Anti-coagulative therapy in patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration: acute angle closure glaucoma after massive intraocular hemorrhage]Ophthalmologe2005102111090109615526102

- PremsenthilMSalowiMASiewCMGudomIAKahTASpontaneous malignant glaucoma in a patient with patent peripheral iridotomyBMC Ophthalmol201214126423241197