Abstract

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic and progressive systemic autoimmune disease that often presents initially with symptoms of dry eye and dry mouth. Symptoms are often nonspecific and develop gradually, making diagnosis difficult. Patients with dry eye complaints warrant a step-wise evaluation for possible SS. Initial evaluation requires establishment of a dry eye diagnosis using a combination of patient questionnaires and objective ocular tests, including inflammatory biomarker testing. Additional work-up using the Schirmer test and tear film break-up time can differentiate between aqueous-deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye. The presence of ADDE should trigger further work-up to differentiate between SS-ADDE and non-SS-ADDE. There are numerous non-ocular manifestations of SS, and monitoring for SS-related comorbid findings can aid in diagnosis, ideally in collaboration with a rheumatologist. The clinical work-up of SS can involve a variety of tests, including tear function tests, serological tests for autoantibody biomarkers, minor salivary gland and lacrimal gland biopsies. Examination of classic SS biomarkers (SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor) is a convenient and non-invasive way of evaluating patients for the presence of SS, even years prior to confirmed diagnosis, although not all SS patients will test positive, particularly those with early disease. Recently, newer biomarkers have been identified, including autoantibodies to salivary gland protein-1, parotid secretory protein, and carbonic anhydrase VI, and may allow for earlier diagnosis of SS. A diagnostic test kit is commercially available (Sjö®), incorporating these new biomarkers along with the classic autoantibodies. This advanced test has been shown to identify SS patients who previously tested negative against traditional biomarkers only. All patients with clinically significant ADDE should be considered for serological assessment for SS, given the availability of new serological diagnostic tests and the potentially serious consequences of missing the diagnosis.

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic and progressive systemic autoimmune disease that primarily involves immune-mediated damage to the lacrimal and salivary glands.Citation1,Citation2 This pathology translates into hallmark clinical symptoms of dry eyes (keratitis sicca or keratoconjunctivitis sicca) and dry mouth. SS is the second most prevalent autoimmune rheumatic disease,Citation2 likely affecting close to four million Americans.Citation3–Citation5 The exact prevalence is difficult to determine due to variations in disease definitions and lack of a diagnostic gold standard. WomenCitation6 and CaucasiansCitation7 are the predominantly affected demographic groups. SS is primarily a disease of middle- to older aged adults, with onset typically occurring in the fourth or fifth decade of life.Citation7 In one large Scandinavian study, the prevalence of SS was approximately seven times higher among elderly individuals (71–74 years of age) compared with a middle-aged population (40–44 years).Citation8 The condition is associated with significant impairments in quality of lifeCitation9–Citation13 and functioning.Citation11,Citation14

While rheumatologists typically oversee the overall care of SS patients, a multidisciplinary team that involves ophthalmology specialists, as well as oral care professionals, is critical not just for the management of known SS patients, but also to identify potential SS cases. The symptoms of SS can progress slowly and are often highly variable in presentation, making diagnosis difficult.Citation3,Citation15–Citation17 Consequently, it is estimated that the disease remains undiagnosed in more than half of affected adults.Citation3,Citation15,Citation18 Data suggest that patients experience symptoms for an average of 3.9 years before a diagnosis of SS is made.Citation5 Unfortunately, such delays in diagnosis can be a source of psychological distress from unexplained symptoms,Citation12 not to mention prolonging the initiation of appropriate treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment of SS is essential to prevent or mitigate development of complications such as cerebrovascular events and myocardial infarction.Citation12,Citation15,Citation16,Citation19–Citation22 Unfortunately, dry eye symptoms are very non-specific, especially in the immediate absence of other SS-related complaints or findings. In a recent US survey of eye care specialists, most practitioners reported relying primarily on patient history to guide treatment decisions.Citation23 These findings underscore the need for reliable objective measures and diagnostic tools to quantify and classify dry eye symptoms.

This review aims to provide eye care professionals with an understanding of methods for distinguishing SS dry eye from other types of dry eye and to describe options for a differential diagnostic approach. The reader is reminded that SS is a systemic disease with many non-ocular manifestations that are not addressed in detail herein, but have been reviewed elsewhere.Citation3 Collaboration with a rheumatologist is essential when SS is suspected in a given patient.

Sjögren’s syndrome

SS can occur alone (primary SS) or in association with another underlying autoimmune disease (secondary SS), typically rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), or polymyositis.Citation7,Citation15,Citation24 The epidemiologic distribution of primary and secondary SS cases seems to be about even.Citation5,Citation25 Ocular and oral symptoms may be somewhat less severe in secondary SS.Citation24 Primary SS presents the greatest diagnostic challenge, given that the disease presents de novo typically with gradual onset of vague, non-specific symptoms.

Primary SS is frequently associated with a wide range of systemic and extraglandular ocular complications, and these usually become evident an average of a decade after the onset of dry eye.Citation21 A large retrospective cohort analysis found that primary SS was associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events and myocardial infarction.Citation22 Patients with primary SS are more than twice as likely as age- and sex-matched controls to have hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia. High rates of depression have also been reported.Citation12 Autonomic symptoms are common, affecting approximately half of patients with primary SS, and they are significantly correlated with overall symptom burden.Citation26 In addition, approximately 20%–30% of patients with primary SS have clinical pulmonary involvement, which is associated with significantly greater impairment in quality of life/physical functioning, as well as with a fourfold increased 10-year mortality.Citation27 Patients with primary SS have an estimated 16–37.5 times increased risk of lymphoma compared to the general population;Citation28,Citation29 the prevalence of non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma specifically is approximately 10%.Citation7

Dry eye disease

Dry eye is one of two classic symptoms of SS, the other being dry mouth. While dry eye is a classic diagnostic feature of SS, it is a very common complaint with a wide range of underlying pathologies, thereby making it quite non-specific for SS by itself.Citation9 The clinical consequences of dry eye include ocular discomfort, visual disturbance, tear film instability, and potential damage to the ocular surface.Citation1 The symptoms of dry eye are usually accompanied by objective findings such as tear hyperosmolarity and ocular surface inflammation.

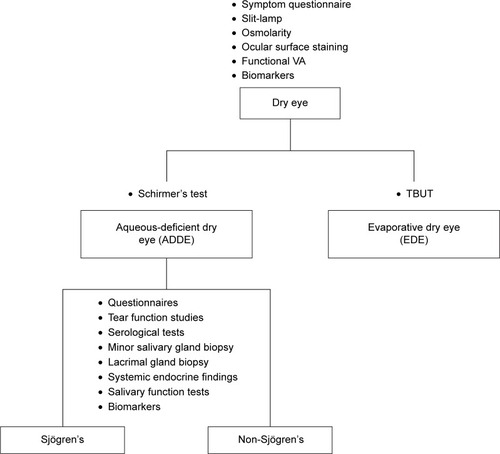

The differential diagnosis of ocular SS begins with a determination of the basic nature of the dry eye, namely aqueous-deficient dry eye (ADDE) or evaporative dry eye (EDE).Citation1 SS falls under the classification of ADDE; therefore, cases of dry eye initially classified as ADDE need to be further investigated as SS dry eye or non-SS dry eye (). Steps for this process are described in the following sections, beginning with strategies for establishing and characterizing a broad diagnosis of dry eye, followed by more detailed methods of distinguishing the various sub-types of dry eye, and specific testing to help confirm a diagnosis of SS.

Figure 1 Overview of the differential diagnosis of dry eye secondary to Sjögren’s syndrome.

As described earlier, dry eye has been categorized based on pathology into two major classes: ADDE and EDE.Citation1 ADDE refers primarily to a failure of lacrimal secretion, although a deficit in conjunctival water secretion may also contribute through decreased production of aqueous fluid by accessory lacrimal glands along the conjunctival surface. ADDE, also called keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), occurs in approximately 4% of adults over 65 years of age.Citation30 EDE is caused by excessive water loss from the ocular surface in patients with normal lacrimal secretion and may be a result of intrinsic (eg, meibomian oil deficiency) or extrinsic (eg, vitamin A deficiency, contact lens wear) factors.Citation1

Despite these classifications and definitions, it is not uncommon for an individual patient to have dry eye caused by more than one mechanism, with subsequent triggering of additional dry eye pathology. Thus, many patients with dry eye have a combination of ADDE and EDE.Citation15,Citation31

General diagnosis of dry eye

A number of tools can be used for the diagnosis of dry eye, including patient questionnaires, objective tests such as slit-lamp evaluation, tear osmolarity assessments, ocular surface staining, functional visual acuity, tear meniscus evaluations, and inflammatory biomarker tests. Ideally, a combination of these assessments should be used.

Symptom questionnaires

The use of a structured symptom questionnaire is considered an excellent way to screen patients for dry eye disease, but should always be used in combination with objective clinical evaluation of dry eye status.Citation31,Citation32 There are several dry eye symptom questionnaires available with varying degrees of length and complexity. The following three-question, evidence-based symptom survey has been suggested as a simple clinical screening tool for dry eye disease; any “yes” response would trigger a more comprehensive dry eye work-up:Citation31

How often do your eyes feel dryness, discomfort, or irritation? Would you say it is often or constantly? (Y/N)

When you have eye dryness, discomfort, or irritation, does this impact your activities (eg, do you stop or reduce your time doing them)? (Y/N)

Do you think you have dry eye? (Y/N)

More extensive questionnaires are used primarily for clinical trials, including the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI)Citation33 and the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire (SPEED).Citation34

Objective ocular testing

Slit-lamp examination is recommended prior to any specific ocular testing; dry eye signs on slit-lamp examination include superficial corneal erosions, insufficient tear lake volume, early tear film break-up time (TBUT), conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctival surface irregularities, and meibomian gland dysfunction.Citation35 Conjunctival scarring may also be seen.

Measurement of tear osmolarity was shown in a prospective, observational case series of 299 patients to have the highest positive predictive value (86%) for the diagnosis of dry eye disease, higher than other objective tests.Citation36 An osmolarity threshold of 308 mOsms/L was noted as a sensitive cut-off for differentiating normal from mild to moderate dry eye disease.Citation36 In a study comparing tear osmolarity in dry eye patients and normal controls, tear osmolarity of 305 mOsm/L was selected as the cut-off value for dry eye, 309 mOsm/L for moderate dry eye, 318 mOsm/L for severe dry eye (with area under the curve values of 0.737, 0.759, and 0.711, respectively).Citation37 Tear osmolarity testing is facilitated and simplified by the availability of commercial devices such as TearLab® (TearLab Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA). TearLab clinical usage guidelines suggest cut-off ranges of 300–320 mOsm/L for mild dry eye and 320–340 mOsm/L for moderate dry eye.Citation38

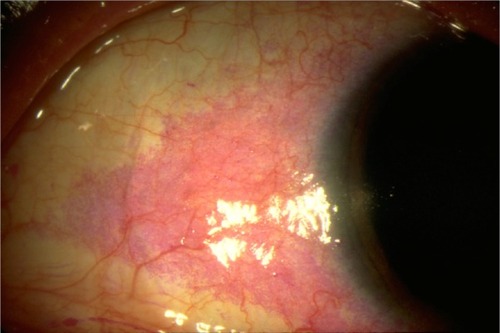

Ocular surface staining patterns can help characterize dry eye and gauge severity. Staining can be performed using fluorescein, Rose Bengal, or lissamine green. Fluorescein concentrates in between living cells, thus stained areas represent an absence of epithelial cells, including cell death. While fluorescein is helpful in identifying superficial epithelial erosions, it is not a very sensitive or specific measure and cannot distinguish dry eye-related damage from other ocular injury.Citation35,Citation39 Rose Bengal and lissamine green stains concentrate in corneal and conjunctival cells that lack a healthy, protective mucin barrier, thereby identifying damaged epithelial cells (). However, these tests also lack sensitivity or specificity for dry eye damage. Lissamine green is usually better tolerated than Rose Bengal.Citation35

Figure 2 Ocular surface of a dry eye patient following Rose Bengal application.

Other tests that may be performed include functional visual acuity and observation of the tear meniscus (tear lake). Functional visual acuity is a measure of visual acuity related to specific daily visual tasks, since patients with dry eye report decreased visual acuity during prolonged concentration on visual tasks such as reading, driving, or working at a computer. Unfortunately, testing of functional visual acuity is subjective and time-consuming.

The tear meniscus reflects the amount of tears present where the bulbar conjunctiva and lower eyelid margin meet. When the height and curvature of the tear meniscus are measured, a patient with dry eye usually has a lower height than a patient without dry eye, though a low tear meniscus can occur in patients without dry eye.Citation35

Biomarkers and other emerging diagnostic techniques

Patients with dry eye generally have higher levels of inflammatory markers than patients without dry eye. The inflammatory biomarker MMP-9 can be detected using the InflammaDry detector (Rapid Pathogen Screening, Inc., Sarasota, FL, USA), a point-of-care MMP-9 test, and it may facilitate making the diagnosis of dry eye. In one clinical trial, the InflammaDry Test was shown to have positive agreement of 86% and negative agreement of 97% with clinical assessment for the diagnosis of dry eye.Citation40 Analysis of tear proteins such as lactoferrin can aid in the diagnosis of dry eye, since it has been shown that tear proteins are decreased in the tears of patients with ADDE, including those with SS and those without SS.Citation41–Citation43

There are a number of promising technologies in various stages of development for dry eye diagnosis, including reflective meniscometry, optical coherence tomography, interferometry, ocular surface thermography, and impression and brush cytology coupled with flow cytometry.Citation32,Citation35 Biopsies are seldom taken clinically.

Differentiating between ADDE and EDE

In patients who present with dry eye, it is important to differentiate between ADDE and EDE, because it is the presence of ADDE that raises the suspicion of SS. However, features of both types of dry eye are often present together.Citation31

There are important differences in tear physiology between ADDE and EDE. There is significantly lower tear turnover in ADDE compared with EDE, while there is considerable overlap observed in tear evaporation between ADDE and EDE. However, there are no differences between the two major dry eye classifications with regard to tear osmolarity, volume, or distribution.Citation44 Although the tear turnover rate has been reported as useful, it is cumbersome and not often used clinically. A cut-off value of 11%/minute for tear turnover rate had a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 75%; a cut-off of 60 g/m2 h for tear evaporation had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 58%.Citation44

The Schirmer test, which measures total tear secretion, can be used to identify ADDE, the type of dry eye primarily associated with SS. In the absence of anesthesia, the Schirmer test measures reflex tearing, while the test performed with anesthesia measures basal tear secretion.Citation31 A Schirmer test result of <5 mm is indicative of aqueous deficiency, >10 mm is normal, and 5–10 mm is considered borderline, but more suggestive of aqueous deficiency if done without anesthesia.Citation32,Citation35 The Schirmer II test is less commonly used; it involves stimulation of the nasal surface with a cotton tip applicator and subsequent measurement of reflex tear production. Drawbacks of the Schirmer test include the length of time required, patient discomfort, and the unreliable nature of the test.Citation32,Citation35

The TBUT is of some value in identifying tear film instability and aiding in the diagnosis of EDE. The established cutoff value for diagnosis of dry eye in general is <10 seconds, although lower cut-off values have been considered.Citation32 Using this cut-off, the TBUT was shown to have a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 86% for differentiating dry eye from non-dry eye.Citation45 However, a more recent investigation found no difference in TBUT between patients with ADDE, EDE, and mixed (ADDE + EDE).Citation46

SS vs other types of ADDE

Once ADDE has been diagnosed, it becomes important to differentiate between SS dry eye (primary vs secondary) and non-SS dry eye. There are many causes of non-SS ADDE, including primary or secondary lacrimal deficiency, lacrimal gland duct obstruction, reflex block (including post-LASIK), other neurotrophic corneas, and systemic drugs. Because SS typically presents in middle-aged women, symptoms such as cutaneous, oral, and vaginal dryness may be misattributed to menopause.Citation3 Symptoms of dry eye and dry mouth may also be confused with atopy or anxiety.Citation3 It is important to ask all patients who present with dry eye about concomitant dry mouth symptoms, as the combination is highly suggestive of SS and should prompt a full diagnostic evaluation. Combined symptoms of dry mouth, sore mouth, and dry eyes correctly classified 93% of patients with SS and 97.7% of controls in one study.Citation47 However, it is possible for SS to present with only one of these findings, and the absence of dry mouth should not be the sole basis for ruling out additional work-up.

The many ocular symptoms of SS may include sensations of itching, grittiness, foreign body sensation, burning, and soreness despite a normal eye appearance.Citation3,Citation48 Patients may complain of photosensitivity, eye fatigue, erythema, reduced and fluctuating visual acuity, discharge, and the sensation of a film across the visual field.Citation3,Citation31 Some patients may not be able to tolerate contact lenses and may report needing to use tear substitutes.Citation48 Accumulation of sticky mucus may make it difficult for patients to open their eyes in the morning.Citation48 Ocular symptoms may be exacerbated by low humidity levels, exposure to cigarette smoke, anticholinergic drugs, antihistamines (as well as several other systemic medications), allergies, computer, tablet, and phone use, and topical drops and preservatives.Citation3

Ocular findings upon examination of SS patients can include diminished tear secretion, although tear flow rates do not correlate with ocular discomfort, and accumulation of mucus secretions along the inner canthus.Citation3,Citation48 Desiccation may result in superficial/shallow erosions of the corneal epithelium; filamentary keratitis, revealed by slit-lamp examination, may occur in more severe cases. Some patients present with conjunctivitis due to infection with Staphylococcus aureus or other organisms. Rarely, enlargement of the lacrimal gland may be seen. Other potential ocular complications of SS include corneal ulceration, vascularization, opacification, and, in rare cases, perforation.Citation3,Citation48

Full diagnostic work-up for SS

Diagnostic criteria for SS were published in 2002Citation49 () and then updated in 2012Citation50 (). The older criteria are more comprehensive, but more recent criteria are considered simpler to apply and rely on more objective measures, including biopsy.Citation50 These criteria can help guide the diagnostic workup for SS, but may require the involvement of multiple specialists, including a rheumatologist.Citation3

Table 1 Revised international classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome (American–European Consensus Group, 2002)

Table 2 Proposed classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome (American College of Rheumatology, 2012)

When SS is suspected in a patient with dry eye, an awareness of the extraocular signs and symptoms of SS can help make the diagnosis.Citation48 These include oral manifestations such as inability to swallow dry food without liquid, dry mouth, parotid swelling, dried and fissured tongue, and dental caries. Involvement of exocrine glands other than lacrimal and salivary glands can result in dry skin and hair, vaginal dryness, and gastrointestinal symptoms associated with impairment of protective mucus secretion. The systemic features of SS are varied and can include fatigue, arthritis (often misdiagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis), interstitial cystitis, neurological involvement, vasculopathies, interstitial pneumonitis, renal disease, lymphoma, and serological abnormalities.

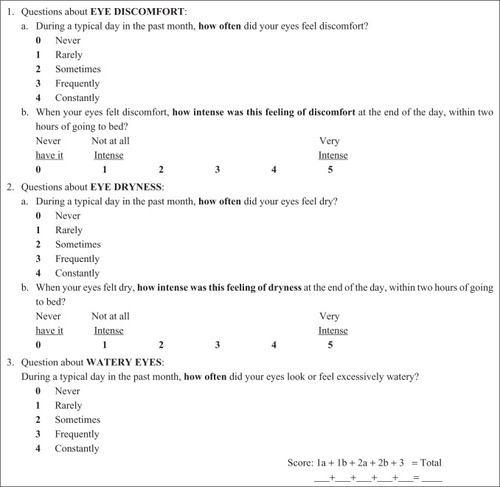

The clinical work-up of SS typically involves a variety of tests, including tear function tests, serological tests for autoantibody biomarkers, minor salivary gland biopsy, lacrimal gland biopsy, systemic endocrine findings, and tests of salivary function (biscuit test, sialography).Citation16,Citation32,Citation51–Citation55 Questionnaires are of some value for the assessment of dry eye etiology,Citation31,Citation56 although questionnaires alone are insufficient to confirm a diagnosis of SS. The 5-item Dry Eye Questionnaire was validated in 2010; scores >6 indicate dry eye, and scores >12 may suggest further testing to rule out SS ().Citation57

Figure 3 The DEQ-5 (5-item Dry Eye Questionnaire), which is designed for patient self-assessment of dry eye severity on a typical day during the past month.

Tear function tests have a role to play in the differential diagnosis of SS, with the most important aspect being differentiating between ADDE and EDE, as discussed earlier. The tear function index has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of SS.Citation58 In addition, Rose Bengal or lissamine green (vital dye stains) staining of the interpalpebral fissure is a noninvasive way to help diagnose SS, because conjunctival staining may be seen earlier in the disease course. A normal TBUT rules out EDE, but a high percentage of patients with SS have a lid margin component (evaporative component).Citation36 However, whether the TBUT is normal or rapid is not helpful for making the diagnosis of SS.

Evaluation of the salivary glands through biopsy or imaging is an important component of SS diagnosis. However, while biopsy of minor salivary glands is traditionally considered the gold standard for diagnosis of SS,Citation3 it is not commonly performed in routine medical practice. Salivary gland ultrasonography has been shown to improve the diagnostic performance of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for SS (salivary gland ultrasonography 60.0% sensitive and 87.5% specific for SS)Citation59 and aid in the differential diagnosis of primary SS.Citation60 Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of the parotid and submandibular glands may also help identify early-stage primary SS (diagnostic sensitivity, 81%; specificity, 67%).Citation61

SS biomarkers

Examination of biomarkers is a convenient and non-invasive way of evaluating patients for the presence of SS. Traditional biomarkers include SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, ANA (antinuclear antibody), and RF (rheumatoid factor)Citation50 (). It has been shown that patients expressing SS-A/Ro antibodies have an increased risk of developing extraglandular manifestations, such as cryoglobulinemia, anemia, vasculitis, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia and thus warrant close monitoring.Citation15 It appears that autoantibodies may be present long before symptom onset; a recent nested case control study from Sweden analyzed 175 serum samples drawn from 117 individuals prior to primary SS diagnosis; among cases which were autoantibody positive after SS diagnosis, at least one autoantibody specificity (ANA, RF, SS-A/Ro60, SS-A/Ro52, SS-B/La) was detected in 81% of cases at a median 4.3–5.1 years preceding SS diagnosis, and as long as 20 years prior.Citation63 In a smaller study, 29/44 (66%) patients with primary SS had detectable autoantibodies as early as 18 years prior to symptom onset.Citation64

Table 3 Traditional and novel biomarkers for diagnosing Sjögren’s syndrome

Although SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, ANA, and RF are considered important in the diagnosis of SS, they are not always positive in patients with SS, especially in early cases. In a large, prospective cohort of patients at optometry and ophthalmology centers within the USA presenting with clinically significant ADDE, 38/327 (11.6%) patients were found to have SS.Citation25 Compared with patients without SS, those with SS demonstrated significantly worse conjunctival and corneal staining, Schirmer’s test results, and symptoms. Primary SS was significantly more likely in patients positive for ANA or RF. However, SS-A/Ro and SS-B/La are positive in only approximately half of patients with SS who present to ophthalmology clinics primarily with dry eye symptoms.Citation15 The authors suggest that patients with clinically significant dry eye signs and symptoms plus ANA and/or RF positivity should be offered diagnostic testing for SS even in the absence of positive SS-A/SS-B results.Citation25

Antibody detection rates may vary by the type of diagnostic test used (ELISA, double immunodiffusion, Western blot, and addressable laser bead assay). For example, in one study, immunodot was able to detect anti-Ro52/60 antibodies in approximately 20% of suspected SS cases who tested negative for anti-SS-A/SS-B findings using ELISA; however, immunodot is expensive and time-consuming.Citation65 Using more than one detection method may improve diagnostic success.

Based on findings in mouse models, it has been hypothesized that SS begins as an organ-specific disease that initially affects the lacrimal and submandibular glands and then progresses to involve the other salivary glands; it has been further postulated that identification of organ-specific antibodies in the lacrimal and major salivary glands may lead to early diagnosis of SS.Citation66 Recent work has identified autoantibodies to salivary gland protein-1 (SP1), parotid secretory protein (PSP), and carbonic anhydrase VI (CA6) in patients with a >5-year history of SS.Citation62,Citation67 Overall, 54% of the SS patients had autoantibodies to SP1, 54% to CA6, and 18% to PSP; 69% had autoantibodies to either SP1 or CA6, while 62% had antibodies to Ro or La, the traditional markers. Upon examination of patients who met the criteria for SS but who lacked antibodies to Ro or La, 45% had autoantibodies to the three novel biomarkers. In addition, among patients with symptoms suggestive of SS for less than 2 years, only 31% were positive for antibodies to Ro or La, while 76% were positive for antibodies to CA6 or SP1.Citation62 In another study, patients with different severities of SS were evaluated, and the novel biomarkers were found to be associated with early disease, with many patients who lacked antibodies to the traditional markers being positive for anti-SP1, anti-CA6, and anti-PSP.Citation67 Thus, these novel biomarkers can be considered as useful markers of early SS.

The Sjö® test (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA) is an advanced, commercially available panel for the early detection of SS, requiring a blood sample obtained by an in-office finger prick or blood collection at a diagnostic laboratory. It includes the early biomarkers SP1, PSP, and CA6, along with the classic Sjögren’s biomarkers SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, ANA, and RF. This combination of biomarkers provides greater sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional testing. The cumulative sensitivity of the Sjö panel was 89.9% as determined from four clinical studies with a total of 248 sera samples. Based on sera samples from 79 age- and sex-matched controls and 64 pediatric controls, the cumulative specificities of the entire Sjö panel and the novel early biomarkers were 78.7% and 82.5%, respectively (personal communication, Dr Lakshmanan Suresh, Immco Diagnostics, Buffalo, NY, USA). Further, incorporation of the early biomarkers into the Sjö test facilitates the diagnosis of SS in patients with chronic dry eye who previously tested negative for traditional anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B biomarkers.Citation67–Citation70 The advent of advanced and easy to use tests such as this may improve diagnostic accuracy in suspected cases of SS and allow for disease identification at earlier stages.

Several additional novel biomarkers of SS have been identified,Citation71,Citation72 but are not yet being used routinely in clinical practice. Anti-kallikrein (KLK) antibodies were found to be significantly higher in the sera of SS patients compared with non-SS dry eye patients or normal controls; using an optical density cut-off of 0.2695, anti-KLK11 antibody distinguished the SS group from non-SS dry eye and controls with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 94%.Citation73 Tear cathepsin S activity is similar in patients with primary and secondary SS but is much higher in SS than in patients with non-specific dry eye disorder or normal controls; very high tear cathepsin S activity may be considered suggestive of SS.Citation74 IgG and IgA antibodies against a-fodrin may be considered activation markers of SS.Citation75 Lymphotoxin α has also been shown to be elevated in salivary gland secretions and sera of patients with SS.Citation76

Conclusion

Patient complaints and clinical findings suggestive of dry eye, especially ADDE, should always trigger a suspicion of SS and prompt further investigation, including queries about concomitant dry mouth symptoms. All patients with clinically significant ADDE should be considered for serological assessment for SS, given the availability of new serological diagnostic tests and the potentially serious consequences of missing the diagnosis. Vigilance and proactive steps on the part of eye care professionals can play a critical role in facilitating the early recognition of SS and referral to a rheumatologist, enabling timely intervention for both ocular and non-ocular manifestations.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance for this paper was provided by the staff of Churchill Communications (Maplewood, NJ, USA) with funding from Bausch & Lomb.

Disclosure

KA Beckman is a paid consultant for Allergan, Bausch & Lomb, Shire, and TearLab; a paid speaker for Allergan and Shire; and an investor in RPS. J Luchs is a paid consultant for Allergan, Alcon, Bausch & Lomb, Shire, Doctor’s Allergy, Tear Lab, Auven, Omeros, AMO; serves on a Speaker’s Bureau for Allergan, Bausch & Lomb, Shire, Doctor’s Allergy, Tear Lab; conducts research for Allergan, Alcon, Bausch & Lomb, Shire, Eleven, Aerie, Auven, Ocular Therapeutics, Topokine, Inotek, Kala, Refocus; and has equity in Insightful Solutions, CXLO, RPS, Calhoun Vision, and Omega Ophthalmics. MS Milner has served as a paid speaker for Allergan, Shire, Bausch & Lomb, and TearScience; has served as a paid consultant/advisory board member for Allergan and Shire; and is an investor in RPS. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AnonymousThe definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007)Ocul Surf200752759217508116

- TincaniAAndreoliLCavazzanaINovel aspects of Sjögren’s syndrome in 2012BMC Med2013119323556533

- KassanSSMoutsopoulosHMClinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjögren syndromeArch Intern Med2004164121275128415226160

- HelmickCGFelsonDTLawrenceRCEstimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part IArthritis Rheum2008581152518163481

- Sjögren’s Syndrome FoundationAbout Sjögren’s syndrome Available from: https://www.sjogrens.org/home/about-sjogrens-syndromeAccessed May 26, 2015

- PillemerSRMattesonELJacobssonLTIncidence of physician-diagnosed primary Sjögren syndrome in residents of Olmsted County, MinnesotaMayo Clin Proc200176659359911393497

- PatelRShahaneAThe epidemiology of Sjögren’s syndromeClin Epidemiol2014624725525114590

- HaugenAJPeenEHulténBEstimation of the prevalence of primary Sjögren’s syndrome in two age-different community-based populations using two sets of classification criteria: the Hordaland Health StudyScand J Rheumatol2008371303418189192

- No authors listedThe epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry EyeWorkShop (2007)Ocul Surf2007529310717508117

- López-JornetPCamacho-AlonsoFQuality of life in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome and sicca complexJ Oral Rehabil2008351287588118976259

- MeijerJMMeinersPMHuddleston SlaterJJHealth-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjögren’s syndromeRheumatology (Oxford)20094891077108219553376

- SegalBBowmanSJFoxPCPrimary Sjögren’s Syndrome: health experiences and predictors of health quality among patients in the United StatesHealth Qual Life Outcomes200974619473510

- LendremDMitchellSMcMeekinPHealth-related utility values of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and its predictorsAnn Rheum Dis20147371362136823761688

- HackettKLNewtonJLFrithJImpaired functional status in primary Sjögren’s syndromeArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201264111760176423111856

- AkpekEKKlimavaAThorneJEMartinDLekhanontKOstrovskyAEvaluation of patients with dry eye for presence of underlying Sjögren syndromeCornea200928549349719421051

- Gomes PdeSJuodzbalysGFernandesMHGuobisZDiagnostic approaches to Sjögren’s syndrome: a literature review and own clinical experienceJ Oral Maxillofac Res201231e324422005

- Hernández-MolinaGSánchez-HernándezTClinimetric methods in Sjögren’s syndromeSemin Arthritis Rheum201342662763923352255

- UsubaFSLopesJBFullerRSjögren’s syndrome: an under-diagnosed condition in mixed connective tissue diseaseClinics (Sao Paulo)201469315816224626939

- MeinersPVissinkAKroeseFABATACEPT treatment reduces disease activity in early primary Sjögren’s syndrome (Phase II Open Label ASAP Study)Ann Rheum Dis20147371393139624473674

- JuarezMTomsTEde PabloPCardiovascular risk factors in women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: United Kingdom primary Sjögren’s syndrome registry resultsArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201466575776424877201

- AkpekEKMathewsPHahnSOcular and systemic morbidity in a longitudinal cohort of Sjögren’s syndromeOphthalmology20151221566125178806

- BartoloniEBaldiniCSchillaciGCardiovascular disease risk burden in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results of a population-based multicentre cohort studyJ Intern Med2015278218519225582881

- WilliamsonJFHuynhKWeaverMADavisRMPerceptions of dry eye disease management in current clinical practiceEye Contact Lens201440211111524508770

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin DiseasesSjogren’s Syndrome62103 Available from: http://www.niams.nih.gov/health_info/Sjogrens_Syndrome/default.asp#versusAccessed August 5, 2015

- LiewMSZhangMKimEAkpekEKPrevalence and predictors of Sjögren’s syndrome in a prospective cohort of patients with aqueous-deficient dry eyeBr J Ophthalmol201296121498150323001257

- NewtonJLFrithJPowellDAutonomic symptoms are common and are associated with overall symptom burden and disease activity in primary Sjögren’s syndromeAnn Rheum Dis201271121973197922562982

- PalmOGarenTBerge EngerTClinical pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, quality of life and mortality – a retrospective study based on registry dataRheumatology (Oxford)201352117317923192906

- Solans-LaqueRLopez-HernandezABosch-GilJPalaciosACampilloMVilardell-TarresMRisk, predictors, and clinical characteristics of lymphoma development in primary Sjögren’s syndromeSemin Arthritis Rheum201141341542321665245

- LazarusMNRobinsonDMakVMollerHIsenbergDAIncidence of cancer in a cohort of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndromeRheumatology (Oxford)20064581012101516490754

- LiuKCHuynhKGrubbsJJrDavisRMAutoimmunity in the pathogenesis and treatment of keratoconjunctivitis siccaCurr Allergy Asthma Rep201414140324395332

- FoulksGNForstotSLDonshikPCClinical guidelines for management of dry eye associated with Sjögren diseaseOcul Surf201513211813225881996

- No authors listedMethodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007)Ocul Surf20075210815217508118

- WaltJRoweMSternKEvaluating the functional impact of dry eye: the Ocular Surface Disease Index (Abstract)Drug Inf J1997311436

- NgoWSituPKeirNKorbDBlackieCSimpsonTPsychometric properties and validation of the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaireCornea20133291204121023846405

- ZeevMSMillerDDLatkanyRDiagnosis of dry eye disease and emerging technologiesClin Ophthalmol2014858159024672224

- LempMABronAJBaudouinCTear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye diseaseAm J Ophthalmol20111515792798.e110.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.032 Epub201121821310379

- VersuraPProfazioVCamposECPerformance of tear osmolarity compared to previous diagnostic tests for dry eye diseasesCurr Eye Res201035755356420597641

- Clinical Workflow. TearLab Inc Available from: http://www.tearlab.com/products/doctors/practice.htmAccessed August 12, 2015

- AbelsonMBIngermanAThe dye-namics of dry-eye diagnosisRev Ophthalmol11152005 Available from: http://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/content/d/therapeutic_topics/i/1311/c/25254/Accessed August 5, 2015

- SamburskyRDavittWFIIIFriedbergMTauberSProspective, multicenter, clinical evaluation of point-of-care matrix metalloproteinase-9 test for confirming dry eye diseaseCornea201433881281824977985

- OhashiYIshidaRKojimaTAbnormal protein profiles in tears with dry eye syndromeAm J Ophthalmol2003136229129912888052

- VersuraPBavelloniAGrilliniMFresinaMCamposECDiagnostic performance of a tear protein panel in early dry eyeMol Vis2013191247125723761727

- KarnsKHerrAEHuman tear protein analysis enabled by an alkaline microfluidic homogeneous immunoassayAnal Chem201183218115812221910436

- KhanalSTomlinsonADiaperCJTear physiology of aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eyeOptom Vis Sci200986111235124019770810

- MengherLSPandherKSBronAJNon-invasive tear film break up time; sensitivity and specificityActa Ophthalmol1986644414443776509

- LempMACrewsLABronAJFoulksGNSullivanBDDistribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective studyCornea201231547247822378109

- Al-HashimiIKhuderSHaghighatNZippMFrequency and predictive value of the clinical manifestations in Sjögren’s syndromeJ Oral Pathol Med20013011611140894

- VenablesPJSjögren’s syndromeBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200418331332915158743

- VitaliCBombardieriSJonssonRClassification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus GroupAnn Rheum Dis200261655455812006334

- ShiboskiSCShiboskiCHCriswellLAmerican College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohortArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201264447548722563590

- VersuraPFrigatoMCelliniMMulèRMalavoltaNCamposECDiagnostic performance of tear function tests in Sjögren’s syndrome patientsEye (Lond)200721222923716397619

- VillaniEGalimbertiDViolaFMapelliCRatigliaRThe cornea in Sjögren’s syndrome: an in vivo confocal studyInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20074852017202217460255

- KojimaTMatsumotoYDogruMTsubotaKThe application of in vivo laser scanning confocal microscopy as a tool of conjunctival in vivo cytology in the diagnosis of dry eye ocular surface diseaseMol Vis2010162457246421139693

- WakamatsuTHSatoEAMatsumotoYConjunctival in vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy in patients with Sjögren syndromeInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci201051114415019696170

- MachettaFFeaAMActisAGde SanctisUDalmassoPGrignoloFMIn vivo confocal microscopic evaluation of corneal langerhans cells in dry eye patientsOpen Ophthalmol J20148515925317216

- AmparoFSchaumbergDADanaRComparison of two questionnaires for dry eye symptom assessment: the ocular surface disease index and the symptom assessment in dry eyeOphthalmology201512271498150325863420

- ChalmersRLBegleyCGCafferyBValidation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnosesCont Lens Anterior Eye2010332556020093066

- KayeSBSimsGWilloughbyCFieldAELongmanLBrownMCModification of the tear function index and its use in the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndromeBr J Ophthalmol200185219319911159485

- CornecDJousse-JoulinSMarhadourTSalivary gland ultrasonography improves the diagnostic performance of the 2012 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndromeRheumatology (Oxford)20145391604160724706989

- HammenforsDSBrunJGJonssonRJonssonMVDiagnostic utility of major salivary gland ultrasonography in primary Sjögren’s syndromeClin Exp Rheumatol2015331566225535773

- KnopfAHofauerBThürmelKDiagnostic utility of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) imaging in primary Sjoegren’s syndromeEur Radiol2015411 Epub ahead of print

- ShenLSureshLLindemannMNovel autoantibodies in Sjögren’s syndromeClin Immunol2012145325125523123440

- TheanderEJonssonRSjostromBBrokstadKOlssonPHenrikssonGPrediction of Sjogren’s syndrome years before diagnosis and identification of patients with early onset and severe disease course by autoantibody profilingArthritis Rheumatol20156792427243626109563

- JonssonRTheanderESjöströmBBrokstadKHenrikssonGAutoantibodies present before symptom onset in primary Sjögren syndromeJAMA2013310171854185524193084

- MekinianANicaise-RolandPChollet-MartinSFainOCrestaniBAnti-SSA Ro52/Ro60 antibody testing by immunodot could help the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome in the absence of anti-SSA/SSB antibodies by ELISARheumatology (Oxford)201352122223222824026249

- XuanJShenLMalyavanthamKPankewyczOAmbrusJLJrSureshLTemporal histological changes in lacrimal and major salivary glands in mouse models of Sjögren’s syndromeBMC Oral Health2013135124093879

- SureshLMalyavanthamKShenLAmbrusJLJrInvestigation of novel autoantibodies in Sjögren’s syndrome utilizing Sera from the Sjögren’s international collaborative clinical alliance cohortBMC Ophthalmol20151513825881294

- BeckmanKADetection of early markers for Sjögren syndrome in dry eye patientsCornea201433121262126425343702

- VishwanathSEverettSShenLMalyavanthamKSureshLAmbrusJLJrXerophthalmia of Sjögren’s Syndrome Diagnosed with Anti-Salivary Gland Protein 1 AntibodiesCase Rep Ophthalmol20145218618925076899

- VishwanathSShenLSureshLAmbrusJLJrAnti-salivary gland protein 1 antibodies in two patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: two case reportsJ Med Case Rep2014814524885364

- GiustiLBaldiniCBazzichiLBombardieriSLucacchiniAProteomic diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndromeExpert Rev Proteomics20074675776718067414

- ZhouLWeiRZhaoPKohSKBeuermanRWDingCProteomic analysis revealed the altered tear protein profile in a rabbit model of Sjögren’s syndrome-associated dry eyeProteomics201313162469248123733261

- El AnnanJJiangGWangDZhouJFoulksGNShaoHElevated immunoglobulin to tissue KLK11 in patients with Sjögren syndromeCornea2013325e90e9323086370

- Hamm-AlvarezSFJangaSREdmanMCTear cathepsin S as a candidate biomarker for Sjögren’s syndromeArthritis Rheumatol20146671872818124644101

- YavuzSTokerEBicakcigilMMumcuGCakirSComparative analysis of autoantibodies against a-fodrin in serum, tear fluid, and saliva from patients with Sjögren’s syndromeJ Rheumatol20063371289129216821267

- ShenLSureshLWuJA role for lymphotoxin in primary Sjögren’s diseaseJ Immunol2010185106355636320952683