Abstract

Purpose

Estrogen, a female hormone, activates collagenase and might be associated with the pathogenesis of vitreoretinal collagen fiber disease. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the vitreous levels of estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2) in subjects with an idiopathic macular hole (IMH).

Methods

Vitreous samples were obtained from ten female patients with an IMH and from nine female patients with other retinal diseases (six with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and three with age-related macular degeneration) as a control at the time of vitreous surgery. E1 and E2 levels in the vitreous samples were then determined using the Coat-A-Count® Estradiol Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kit and the DSL-70 Estrone RIA Kit, respectively.

Results

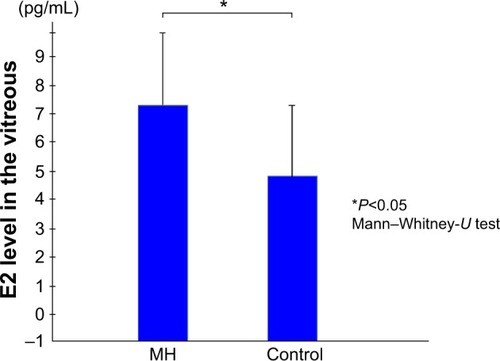

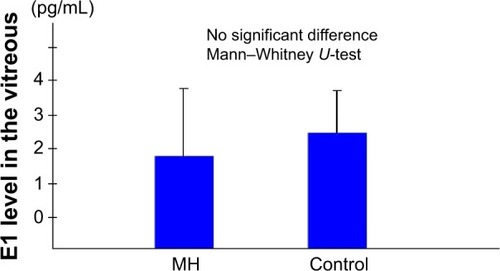

The mean vitreous levels of E1 and E2 in the subjects with IMH were 1.83±2.00 pg/mL and 7.03±2.97 pg/mL, respectively, whereas in the control subjects they were 2.42±1.25 pg/mL and 4.90±2.90 pg/mL, respectively. Thus, the vitreous E2 levels in the subjects with IMH were significantly higher than in the controls (P<0.05).

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that E2 might be associated with the pathogenesis of IMH, but further investigation is needed to elucidate that association.

Introduction

Idiopathic full-thickness macular hole (IMH) is an important cause of poor vision in the elderly that affects predominantly women older than 60 years. Kishi et al reported that tangential traction, which appears to originate exclusively in the premacular vitreous cortex that forms the posterior wall of the premacular liquefied pocket, causes IMHs.Citation1 Although it is accepted that vitreoretinal traction is an important local factor in the development of an IMH, the systemic risk factors of IMH remain unclear.

Estrogen has many effects on various tissues, such as bone and the cardiovascular system, in addition to the genitals, through classical nuclear receptors and cellular membrane receptors.Citation2–Citation11 Estrogen is also known to be associated with the growth of central nerve fibers, and estrogen receptors are reportedly present in the retina.Citation12,Citation13 The incidence of IMHs is higher in females, and a high incidence of systemic estrogen therapy has been reported in IMH patients.Citation14,Citation15 However, other studies have reported no association with estrogen exposure.Citation16 Thus, a possible association between IMH and estrogen remains controversial.

Estrogen reportedly increases the biosynthesis of hyaluronic acid in the skin of mice.Citation17 Estrogen activates collagenase and also reportedly has an effect on collagenase production in the cervix of guinea pigs.Citation18 If the metabolic change of estrogen after menopause affects ocular collagen metabolism, it might consequently induce constriction of the posterior vitreous membrane and macular hole. To elucidate the association between estrogen and IMHs, we investigated vitreous estrogen levels in IMH patients.

Methods

Subjects

In this study, ten eyes of ten female patients (age, 62.3±6.18 years) undergoing a vitrectomy for an IMH were examined. As a control, nine eyes of nine female patients (mean age, 62.9±12.3 years) undergoing a vitrectomy for retinal detachment (six patients) and age-related macular degeneration (three patients) were examined.

Sample preparation

Pure vitreous samples (0.5~1.0 mL) were obtained from each patient before initiating intraocular infusion at the time of vitreous surgery. All samples were frozen at 80°C immediately after being obtained.

Radioimmunoassay

The levels of estradiol (E2) and estrone (E1) in each sample were determined, using the Coat-A-CountR Estradiol Radioimmunoassay (RIA) Kit (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and the DSL-70 Estrone RIA Kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX, USA), respectively. This measuring system also included the interference tests.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between the groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U-test, and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean E2 levels in the vitreous samples obtained from the IMH patients was 7.03±2.97 pg/mL, which was significantly higher than the level in the vitreous samples obtained from the controls (4.90±2.90 pg/mL; P<0.05) (). The mean E1 level in the vitreous samples obtained from the IMH patients was 1.83±2.00 pg/mL, which was not significantly different from that in the vitreous samples obtained from the controls (2.42±1.25 pg/mL) ().

Figure 1 Vitreous E2 levels.

Abbreviations: E2, estradiol; MH, patients with an idiopathic macular hole.

Figure 2 Vitreous E1 levels.0

Abbreviations: E1, estrone; MH, patients with an idiopathic macular hole.

Discussion

In postmenopausal women, the primary source of estrogen is the adrenal gland, which secretes dehydroepiandrosterone. Dehydroepiandrosterone is converted by steroidogenic enzymes to estrogens in peripheral tissues.Citation9,Citation19 Estrogen readily passes through the blood–retinal barrier, and vitreous estrogen is known to be transported from the adrenal gland via blood circulation. In contrast, abundant P450 aromatase is reportedly detectable in the retina of goldfish.Citation20,Citation21 Androstenedione is converted to estrogen by P450 aromatase.Citation22,Citation23 If P450 aromatase is expressed in the human eye, local production of estrogen may be the result of an alternating supply source. The findings of this present study show that in patients with an IMH, vitreous E2 levels were higher than E1 levels. E2 is believed to be converted from E1 by 17-β hydroxy-dehydrogenase in the eye. This is the first report that evaluated vitreous estrogen levels in patients with an IMH. However, to elucidate the local metabolism of estrogen, further experimental studies will be needed.

E2 exerts the strongest biological activity among the various natural estrogens (E1, E2, and Estriol). Estrogen receptors have a strong affinity for estrogen, which is known to be biologically active even at extremely low levels, and they have reportedly been detected in the retina.Citation12 In the present study, the observed vitreous E2 levels in the IMH patients were considered more than adequate for biological activity. Vitreous E2 is suggested to have some effect on the eye. Contraction of the posterior vitreous membrane is considered to be one of the steps in the pathogenesis of IMHs. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of estrogen on the vitreous membrane has not yet been elucidated. Previous studies have shown that estrogen has an effect on collagen metabolism and hyaluronic acid production in the skin,Citation16,Citation17 and it is believed to have effects on the posterior vitreous membrane. However, those effects have yet to be identified.

Another pathogenesis to clarify the association between estrogen and IMH is related to chymase, a serine protease. Previous studies have reported that chymase converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II; converts latent transforming growth factor 1 to active transforming growth factor 1, which cleaves procollagen to produce collagen type IV; facilitates collagen degradation by activating matrix metalloproteinase, a catabolic enzyme of extracellular matrix; and inactivates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor.Citation24,Citation25 In addition, chymase is reportedly involved in the degradation of type VI collagen.Citation26 Therefore, chymase may be involved in the onset of IMH formation through the production and degradation of collagen.

We previously investigated chymase involvement in the onset of IMH formation, as well as the effects of chymase on monkey eyes and cultured Muller cells.Citation27,Citation28 Interestingly, chymase activity in the vitreous humor from IMH patients is the most activated among the vitreoretinal diseases.Citation27 Moreover, thickening of the posterior hyaloid membrane and some apoptotic cells were found in the macula of the chymase-treated monkey eyes. These findings suggest that increased chymase activity may result in IMH onset.

Chymase is produced by mast cells, and mast cells have been reported to be involved in tissue fibrosis and neovascularization.Citation29 In the eye, mast cells are reportedly present in the choroid, ciliary body, conjunctiva, and sclera.Citation30 Nicovani et al reported the presence of estrogen receptors in vascular mast cells and a possible genomic effect of estrogens on the expression of mast cell mediators such as chymase, tumor necrosis factor alpha, nitric oxide synthase, and interleukin 10.Citation31 These data illustrate that estrogen can directly modify vascular mast cell activity.

Furthermore, there might be two possibilities that explain the high concentrations of E2 in IMH patients. The first possibility is that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin 6 are known to disrupt the normal activity of steroidogenic enzymes and promote the aromatization of testosterone to E2. In fact, some previous studies have reported that these proinflammatory cytokines were significantly higher in the vitreous of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy.Citation32,33 In this study, we did not investigate the concentration of these proinflammatory cytokines; however, that possibility should be taken into consideration.

The second possibility is the effects by glucuronidation. Glucuronidation is reportedly the major pathway for estrogen inactivation in humans,Citation9,Citation19 and the results shown in that study were altered by glucuronidated E2 and E1. In this study, we did not measure glucuronidated E2 and E1, so further investigation is necessary to confirm this point.

In conclusion, one of the limitations of this current investigation is that it was conducted as a pilot study because of the small number of subjects involved. Further investigation and considerations are necessary to elucidate the association between estrogen and the pathogenesis of IMHs.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Bush for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KishiSHagimuraNShimizuKThe role of the premacular liquefied pocket and premacular vitreous cortex in idiopathic macular hole developmentAm J Ophthalmol199612256226288909201

- ColburnPBuonassisiVEstrogen-binding sites in endothelial cell culturesScience19782014358817819684408

- StampferMJColditzGAWillettWCPostmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the nurses’ health studyN Engl J Med1991325117567621870648

- OrimoAInoueSIkegamiAVascular smooth muscle cells as target for estrogenBiochem Biophys Res Commun199319527307367690560

- WalshBWSchiffIRosnerBGreenbergLRavnikarVSacksFMEffects of postmenopausal estrogen replacement on the concentrations and metabolism of plasma lipoproteinsN Engl J Med199132517119612041922206

- SmithEPBoydJFrankGREstrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a manN Engl J Med199433116105610618090165

- WickelgrenIEstrogen stakes claim to cognitionScience199727653136756789157544

- TangMXJacobsDSternYEffect of oestrogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer’s diseaseLancet199634890254294328709781

- LabrieFDHEA, important source of sex steroids in men and even more in womenProg Brain Res20101829714820541662

- KackerRTraishAMMorgentalerAEstrogens in men: clinical implications for sexual function and the treatment of testosterone deficiencyJ Sex Med2012961681169622512993

- VrtačnikPOstanekBMencej-BedračSMarcJThe many faces of estrogen signalingBiochem Med (Zagreb)201424332934225351351

- Toran-AllerandCDMirandaRCBenthamWDEstrogen receptors colocalize with low-affinity nerve growth factor receptors in cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrainProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19928910466846721316615

- KobayashiKKobayashiHUedaMHondaYEstrogen receptor expression in bovine and rat retinasInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci19983911210521109761289

- McDonnellPJFineSLHillisAIClinical features of idiopathic macular cysts and holesAm J Ophthalmol19829367777867091263

- JamesMFemanSSMacular holesAlbrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol1980215159636906170

- The Eye Disease Case-Control Study GroupRisk factors for idiopathic macular holesAm J Ophthalmol199411867547617977602

- UzukaMNakajimaKOhtaSMoriYThe mechanism of estrogen-induced increase in hyaluronic acid biosynthesis, with special reference to estrogen receptor in the mouse skinBiochim Biophys Acta198062721992067350923

- RajabiMRSolomonSPooleARActivation of protein kinase C stimulates collagenase production by cultured cells of the cervix of the pregnant guinea pigAm J Obstet Gynecol199216711942001442926

- Luu-TheVLabrieFThe intracrine sex steroid biosynthesis pathwaysProg Brain Res201018117719220478438

- GelinasDCallardGVImmunocytochemical and biochemical evidence for aromatase in neurons of the retina, optic tectum and retinotectal pathways in goldfishJ Neuroendocrinol1993566356418680435

- CallardGVDrygasMGelinasDMolecular and cellular physiology of aromatase in the brain and retinaJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol1993444–65415478476767

- SimpsonERubinGClyneCLocal estrogen biosynthesis in males and femalesEndocr Relat Cancer19996213113710731101

- BulunSEZeitounKSasanoHSimpsonERAromatase in aging womenSemin Reprod Endocrinol199917434935810851574

- JohnsonJLJacksonCLAngeliniGDGeorgeSJActivation of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases by mast cell proteases in atherosclerotic plaquesArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol19981811170717159812908

- FrankBTRossallJCCaugheyGHFangKCMast cell tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 is cleaved and inactivated extracellularly by alpha-chymaseJ Immunol200116642783279211160345

- KieltyCMLeesMShuttleworthCAWoolleyDCatabolism of intact type VI collagen microfibrils: susceptibility to degradation by serine proteinasesBiochem Biophys Res Commun19931913123012368466500

- MaruichiMOkuHTakaiSMeasurement of activities in two different angiotensin II generating systems, chymase and angiotensin-converting enzyme, in the vitreous fluid of vitreoretinal diseases: a possible involvement of chymase in the pathogenesis of macular hole patientsCurr Eye Res2004294–532132515590479

- SugiyamaTKatsumuraKNakamuraKEffects of chymase on the macular region in monkeys and porcine muller cells: probable involvement of chymase in the onset of idiopathic macular holesOphthalmic Res200638420120816679808

- QuZLieblerJMPowersMRMast cells are a major source of basic fibroblast growth factor in chronic inflammation and cutaneous hemangiomaAm J Pathol199514735645737545872

- MayCAMast cell heterogeneity in the human uveaHistochem Cell Biol1999112538138610603078

- NicovaniSRudolphMIEstrogen receptors in mast cells from arterial wallsBiocell2002261152412058378

- SuzukiYNakazawaMSuzukiKYamazakiHMiyagawaYExpression profiles of cytokines and chemokines in vitreous fluid in diabetic retinopathy and central retinal vein occlusionJpn J Ophthalmol201155325626321538000