Abstract

Purpose

To compare the degree of surgical-field contamination in cataract surgeries between a new draping method using a lid speculum with a drape (LiDrape®) and a conventional draping method.

Methods

Cataract surgery was performed on 21 eyes using LiDrape® (LiDrape® group) and on 22 eyes using a conventional draping method (conventional group). Contamination was evaluated by bacterial culture of conjunctival sac scrapings and ocular surface irrigation fluid. Conjunctival sac scrapings were collected before and after application of preoperative antibiotics. Ocular surface irrigation fluid was collected before incision placement and during surgery. Bacterial detection rate and types of organisms isolated at these four time points were examined.

Results

Bacterial detection rates were significantly decreased in the LiDrape® group at all time points after the application of antibiotics compared with preapplication. Regarding between-group comparisons, the bacterial detection rate in the LiDrape® group was only significantly lower than that in the conventional group in the intraoperative sample. Propionibacterium acnes was the most common organism isolated from ocular surface irrigation fluid. The number of P. acnes in the intraoperative sample was significantly lower in the LiDrape® group compared with the conventional group. There were no significant differences in detection rates for other bacteria between the groups.

Conclusion

LiDrape® was as effective as conventional draping for preventing surgical-field contamination. The number of P. acnes during surgery was significantly lower in the LiDrape® group compared with the conventional group, suggesting that LiDrape® may contribute to the prevention of postoperative infection.

Introduction

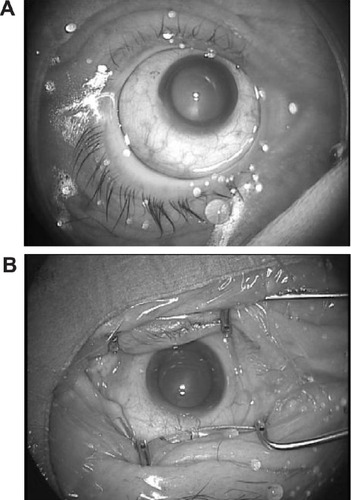

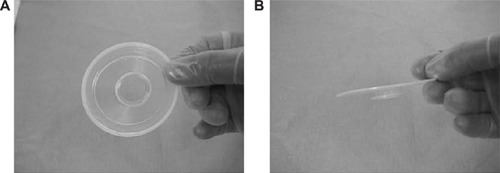

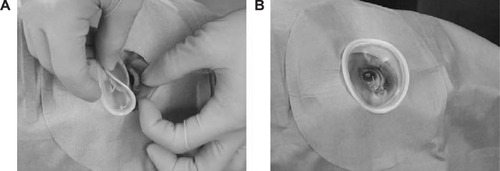

The introduction of small-incision cataract surgery has led to a reduction in surgical complications. However, postoperative endophthalmitis remains a serious complication, with a reported incidence of 0.04%–0.14% since the 1990s. Various different prophylactic measures have been taken to prevent postoperative endophthalmitis.Citation1–Citation7 Speaker et al demonstrated, by genetic analysis of the isolates from the patient’s eyelid, conjunctiva, and vitreous, that microbial flora of patients’ own eyelid and conjunctiva can be a cause of postoperative endophthalmitis.Citation8 Appropriate draping isolates the surgical field from the eyelashes and prevents periocular skin exposure and invasion of microorganisms into the eye. Inappropriate draping has been reported as a risk factor for endophthalmitis.Citation9,Citation10 However, it is difficult to drape the eyelashes and the eyelids completely using conventional draping methods. Urano et alCitation11 developed a disposable lid speculum with a drape (LiDrape®, Hakko Co., Ltd., Nagano, Japan) for simple and complete draping of the eyelashes and eyelids to ensure an appropriate surgical field ( and ). In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of this newly developed lid speculum in patients undergoing cataract surgeries (phacoemulsification and aspiration plus intraocular lens implantation) and compared the degrees of surgical-field contamination between the LiDrape® and conventional draping methods.

Figure 1 LiDrape®.

Figure 2 LiDrape® attachment procedure.

Participants and methods

This study was approved by the Kurume University Institutional Review Board. Each patient gave informed consent prior to participation. The study protocol complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The new draping method with LiDrape® was used in operations on 21 eyes of 21 patients with a mean age of 72.2±12.3 years (LiDrape® group), while a conventional draping method was used in operations on 22 eyes of 22 patients with a mean age of 72.2±12.4 years (conventional group). The patients’ demographic characteristics are shown in . The degree of surgical-field contamination was compared between the groups. All surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (RY), and all patients received preoperative antibiotic treatment with gatifloxacin (Gatiflo® 0.3%, Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) three times a day for 3 days plus a single application 1 hour before surgery and intraoperative infusion of cefotiam hydrochloride.

Table 1 Patient characteristics

Conjunctival scrapings were collected by a single ophthalmologist (TU) at the outpatient clinic using Transwab® (MWE-TS, Medical Wire & Equipment Co. Ltd., Wiltshire, UK) before the application of preoperative antibiotics, but within 2 months prior to surgery, again after antibiotic application, and immediately before surgery in the operating room.

Ocular surface irrigation fluid was collected before incision placement and during surgery in the operating room, using the following procedure. Eyewash was performed with potash soap followed by 50 mL of 16-fold diluted povidone–iodine solution (8 mL of 10% povidone–iodine +120 mL normal saline solution) for approximately 20–30 seconds, and the eyelids were disinfected using an undiluted 10% povidone–iodine-soaked swab. Patients were draped with disposable perforated ophthalmic sheet. LiDrape® was placed in the LiDrape® group (), while an adhesive sheet (Tegaderm™, 3M Healthcare, St Paul, MI, USA) was applied to cover the eyelashes and eyelids, and a suction-type speculum was placed in the conventional group (). After placement of the speculum, the ocular surface was irrigated with 20 mL of 16-fold diluted povidone–iodine for approximately 20–30 seconds. The ocular surface and conjunctiva were then flushed with 20 mL of balanced salt solution (BSS PLUS®, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) using a syringe, and the fluid on the ocular surface was collected as the preincision sample. A sclerocorneal or corneal incision was made. Irrigation fluid used to prevent the corneal surface from drying out and irrigation fluid that flowed out of the eye during phacoemulsification, intraocular lens implantation, removal of viscoelastic material, and checking wound closure were collected as the intraoperative fluid sample.

Bacterial identification tests were performed at the Department of Clinical Laboratory Medicine at Kurume University Hospital. Samples from conjunctival sac scrapings were subjected to direct culture followed by enrichment culture for up to 2 weeks. Bacterial detection rates (the number of eyes with positive cultures per total number of eyes in each group) and types of organisms isolated from samples collected at four different time points were examined. The details of the culture media and conditions are given in .

Table 2 Culture medium and incubation conditions

One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison tests were used for within-group comparisons, and Fisher’s exact probability tests were used for between-group comparisons. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

The mean operation times were 22.1±4.7 minutes in the LiDrape® group and 20.9±4.4 minutes in the conventional group. There was no significant difference between the groups (P=0.758, Student’s t-test) ().

Contamination in the conjunctival sac

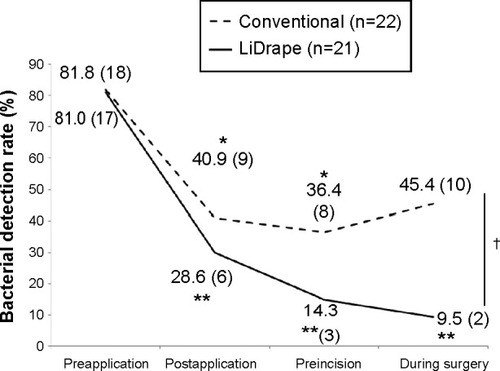

The bacterial detection rate was 81.0% (17/21 eyes) in the LiDrape® group and 81.8% (18/22 eyes) in the conventional group before a 3-day application of preoperative antibiotics, and 28.6% (6/21 eyes) in the LiDrape® group and 40.9% (9/22 eyes) in the conventional group after antibiotic application. Detection rates were significantly lower after antibiotic application in both groups (P<0.01 for LiDrape® group and P<0.05 for conventional group, Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison tests), compared with preapplication rates, but there was no significant difference between the groups.

The most common organism isolated from postapplication samples was Propionibacterium acnes, and the number of strains of P. acnes increased after antibiotic application in both groups ().

Table 3 Results of bacterial detection and bacterial species identification

Contamination in ocular surface irrigation fluid

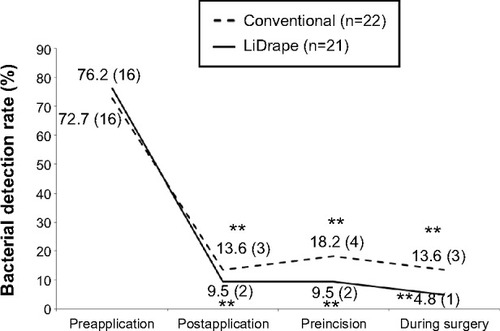

The bacterial detection rate was 14.3% (3/21 eyes) in the LiDrape® group and 36.4% (8/22 eyes) in the conventional group before incision placement, and it was 9.5% (2/21 eyes) in the LiDrape® group and 45.4% (10/22 eyes) in the conventional group during surgery (). The detection rate in the conventional group increased as the surgical procedure advanced, but there was no significant difference between the preapplication and intraoperative detection rates. In contrast, no such increase occurred in the LiDrape® group as surgery proceeded, and the intraoperative detection rate was significantly lower than the preantibiotic application rate (P<0.01, Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test). Comparing between the groups, the detection rate was only significantly lower in the LiDrape® group compared with the conventional group during surgery (P=0.0157, Fisher’s exact probability test) ().

Figure 4 Bacterial detection rates.

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

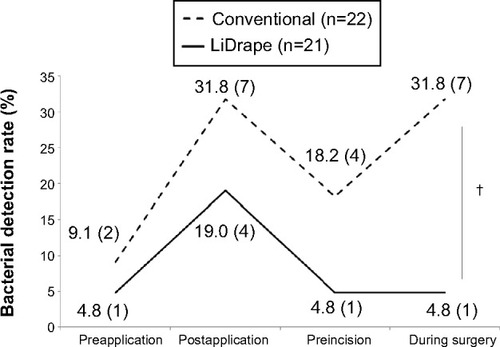

P. acnes was the most common organism isolated from postantibiotic samples. In the conventional group, the number of P. acnes decreased before incision placement but increased again during surgery, while in the LiDrape® group, the number of P. acnes decreased before incision placement and remained decreased during surgery. There were no significant differences in trends in numbers of other microorganisms between the groups (). The number of P. acnes isolated from the intraoperative sample in the LiDrape® group was significantly lower than from the conventional group (P=0.0459, Fisher’s exact probability test) ().

Figure 5 Detection rates of bacteria other than P. acnes.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; P. acnes, Propionibacterium acnes.

Figure 6 Detection rates of P. acnes.

Abbreviation: P. acnes, Propionibacterium acnes.

Discussion

Preoperative and intraoperative antibiotic prophylactic measures are considered to contribute to sterilization of the surgical field. In the current study, surgical-field contamination rates were lower in both draping groups after the preoperative application of antibiotics, compared with the preapplication rates. This finding is consistent with that of Inoue et al.Citation12 However, in terms of between-group comparisons, the bacterial detection rate was only significantly lower in the LiDrape® group compared with the conventional group during the intraoperative period. Although the intraoperative detection rate in the conventional group was lower than the preapplication rate, the difference was not significant. The bacterial detection rate in the LiDrape® group continued to be significantly lower throughout the course, compared with the preapplication rate.

The numbers of P. acnes isolates fluctuated in both groups. P. acnes is a member of the normal resident microbiota of the skin and resides in sebaceous glands and hair follicles. It has been reported to cause late-onset endophthalmitis after surgery.Citation13,Citation14 P. acnes has also been reported to be difficult to eliminate with disinfection.Citation12 In the present study, the number of P. acnes isolates increased in both groups after preoperative application of antibiotics and subsequently decreased before incision. However, P. acnes increased again during surgery in the conventional group. P. acnes has been reported to be increased by preoperative conjunctival irrigation.Citation15 Conventional draping makes it difficult to isolate the ocular surface from the eyelids and periocular skin completely. It is therefore possible that bacteria residing on the periocular skin might gain entry into the eye during cataract surgery, via the irrigation fluid used to maintain the anterior chamber and visualization of the surgical field or to moisten the ocular surface, potentially leading to infection.

The LiDrape® lid speculum was developed to provide a constant physical block between the surgical field and the periocular skin and eyelids. The surgeon described that the LiDrape® was easier to use and more reliable than conventional draping methods. The levels of surgical-field sterilization of the LiDrape® were similar to those achieved using conventional draping. The physical isolation of the surgical field provided by the LiDrape® was effective in preventing contamination by P. acnes, which is resistant to chemical disinfection. These results suggest that the LiDrape® is a promising device for helping prevent postoperative endophthalmitis.

The potential limitations of this study included its small sample size and its restriction to cataract surgery. Further studies with larger samples and other types of surgeries are warranted to examine the effects of LiDrape® on the elimination of bacteria from the surgical field. Shimada et al reported that repeated irrigation of the operative field with 0.25% povidone–iodine during cataract surgery led to an extremely low bacterial contamination rate in the anterior chamber at the end of surgery.Citation16 This irrigation method in addition to the use of LiDrape® may lead to further sterilization of surgical field.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EifrigCWFlynnHWJrScottIUNewtonJAcute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis: review of incidence and visual outcomes (1995–2001)Ophthalmic Surg Lasers200233537337812358290

- MontanPLundströmMSteneviUThorburnWEndophthalmitis following cataract surgery in Sweden. The 1998 national prospective surveyActa Ophthalmol Scand200280325826112059862

- KamalarajahSSilvestriGSharmaNSurveillance of endophthalmitis following cataract surgery in the UKEye200418658058715184923

- WongTYCheeSPThe epidemiology of acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in an Asian populationOphthalmology2004111469970515051201

- WejdeGMontanPLundströmMSteneviUThorburnWEndophthalmitis following cataract surgery in Sweden: national prospective survey 1999–2001Acta Ophthalmol Scand200583171015715550

- MillerJJScottIUFlynnHWJrSmiddyWENewtonJMillerDAcute-onset endophthalmitis after cataract surgery (2000–2004): incidence, clinical settings, and visual acuity outcomes after treatmentAm J Ophthalmol2005139698398715953426

- OshikaTHatanoHKuwayamaYIncidence of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery in JapanActa Ophthalmol Scand200785884885117459028

- SpeakerMGMilchFAShahMKEisnerWKreiswirthBNRole of external bacterial flora in the pathogenesis of acute postoperative endophthalmitisOphthalmology19919856396492062496

- LuskJELanierJDThe incise drapeOphthalmic Surg198011107227246969874

- BuzardKLiapisSPrevention of endophthalmitisJ Cataract Refract Surg20043091953195915342061

- UranoTKasaokaMYamakawaRTamaiYNakamuraSDevelopment of a novel disposable lid speculum with a drapeClin Ophthalmol201371575158023950638

- InoueYUsuiMOhashiYShiotaHYamazakiTPreoperative Disinfection Study GroupPreoperative disinfection of the conjunctival sac with antibiotics and iodine compounds: a prospective randomized multicenter studyJpn J Ophthalmol200852315116118661264

- PiestKLKincaidMCTetzMRAppleDJRobertsWAPriceFWJrLocalized endophthalmitis: a newly described cause of the so-called toxic lens syndromeJ Cataract Refract Surg19871354985103499503

- MeislerDMMandelbaumSPropionibacterium-associated endophthalmitis after extracapsular cataract extraction. Review of reported casesOphthalmology198996154612783995

- IsenbergSAptLYoshimuriRChemical preparation of the eye in ophthalmic surgery: I. Effect of conjunctival irrigationArch Ophthalmol198310157617636847465

- ShimadaHAraiSNakashizukaHHattoriTYuzawaMReduction of anterior chamber contamination rate after cataract surgery by intraoperative surface irrigation with 0.25% povidone-iodineAm J Ophthalmol20111511111720970112