Abstract

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a distinct subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a unique morphological appearance, associated coagulopathy and canonical balanced translocation of genetic material between chromosomes 15 and 17. APL was first described as a distinct subtype of AML in 1957 by Dr Leif Hillestad who recognized the pattern of an acute leukemia associated with fibrinolysis, hypofibrinogenemia and catastrophic hemorrhage. In the intervening years, the characteristic morphology of APL has been described fully with both classical hypergranular and variant microgranular forms. Both are characterized by a balanced translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17, [t(15;17)(q24;q21)], giving rise to a unique fusion gene PML-RARA and an abnormal chimeric transcription factor (PML-RARA), which disrupts normal myeloid differentiation programs. The success of current treatments for APL is in marked contrast to the vast majority of patients with non-promyelocytic AML. The overall prognosis in non-promyelocytic AML is poor, and although there has been an improvement in overall survival in patients aged <60 years, only 30%–40% of younger patients are still alive 5 years after diagnosis. APL therapy has diverged from standard AML therapy through the empirical discovery of two agents that directly target the molecular basis of the disease. The evolution of treatment over the last 4 decades to include all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide, with chemotherapy limited to patients with high-risk disease, has led to complete remission in 90%–100% of patients in trials and rates of overall survival between 86% and 97%.

Background

The discovery of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) arose from early case reports of patients who presented with an acute leukemia and bleeding preponderance. Building on these published case reports, Dr Hillestad identified the common characteristics of this new and rapidly fatal disease.Citation1–Citation5 A subsequent more detailed report on 20 patients treated at the Hôpital St Louis in Paris by Jean Bernard increased early understanding of this unique disease.Citation6 APL accounts for 3%–13% of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) based on data from UK and Swedish registries.Citation7,Citation8 It has been reported that the incidence of APL is higher in populations originating from Central and South America, where APL may constitute 28% of AML cases.Citation9,Citation10

The characteristic morphology of APL has been described fully; first, the typical or hypergranular form of APL with characteristically abnormal promyelocytes exhibiting a densely granulated cytoplasm, Auer rods or Faggot cells (cells with bundles of Auer rods) and a nuclear membrane that is often reniform or bilobed.Citation11 A microgranular variant associated with a high white cell count (WCC) and predominantly bilobed nuclei was described later.Citation12 Both forms were found to be associated with a balanced translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17, [t(15;17)(q24;q21)], giving rise to a unique fusion gene PML-RARA.Citation13,Citation14 There are rarer cryptic and complex cytogenetic rearrangements that have been identified giving rise to a PML-RARA fusion; furthermore, variant gene fusion partners for the RARA gene not involving the PML locus have been described. The 2016 update of the WHO classification of myeloid neoplasms and myeloid malignancies specifically describes APL with PML-RARA to distinguish it from these other entities.Citation15,Citation16 AML is recognized as a heterogenous disease, often with co-existing somatic mutations, contributing to its clonal evolution, relapse and poor overall survival (OS). In contrast, APL appears to be a less heterogeneous disease with a smaller portfolio of associated genetic mutations and thus a greater sensitivity to therapy. A recent mutational analysis of primary and relapse APL cases identified mutations in genes for Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) and N-RAS most commonly. However, mutations in genes recognized as recurring sites of genetic mutations in AML such as DNMT3A, NPM1, IDH1/2, RUNX1, TP53, TET2 and CEBPA are absent or rarely present.Citation17

The success of current treatments for APL is unparalleled and in marked contrast to the vast majority of patients with non-promyelocytic AML who can expect a 5-year OS of 30%–40%,Citation18–Citation21 although it is accepted that patients diagnosed with AML with the so-called favorable cytogenetic rearrangements t(8;21)(q22;q22.1); RUNX1-RUNX1T1, inv(16) (p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22);CBFB-MYH11 have a 5-year OS between 55% and 69%.Citation22–Citation24 Similarly, patients with normal cytogenetics and concurrent mutations in the nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) gene (without FLT3 internal tandem duplications [ITDs]) or those possessing bi-allelic mutations of CEBPA can expect a 5-year OS between 50% and 70%.Citation25–Citation34

APL therapy has evolved through the empirical discovery of two agents that directly target the molecular foundation of the disease. The evolution of treatment over 4 decades to include all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), arsenic trioxide (ATO) and chemotherapy in a variety of protocols has led to complete remission (CR) in 90%–100% of patients in trials and rates of OS between 86% and 97%.Citation35–Citation42

Chemotherapy era

The first therapeutic breakthrough in the treatment of APL was the introduction of anthracyclines. Prior to this, early case reports showed that only 6%–14% entered remission and the majority of patients died within 4 weeks.Citation43–Citation45 In 1973, Bernard et alCitation46 reported in a review of 80 patients that daunorubicin as monotherapy increased CR rates from 13% to 55%. The effectiveness of anthracycline-based treatment was subsequently confirmed by European and North American researchers, including the use of an anthracycline as a single agent. These studies showed CR rates between 55% and 88%, with 35%–45% of patients entering a prolonged remission.Citation47–Citation56 The effectiveness of anthracycline-based treatment appeared to be dose dependent, with higher doses of daunorubicin improving remission rates.Citation57 Thus, in the pre-ATRA era, patients diagnosed with APL typically underwent chemotherapy induction with an anthracycline and cytarabine, eg, the “7–3” regimen, similar to non-APL AML. However, unlike non-APL AML, there was no demonstrable benefit in APL when cytarabine was added to an anthracycline during induction therapy in APL.Citation48,Citation50,Citation58

ATRA era

The concept of differentiation therapy arose from an improved understanding of cancer cell biology, such as the demonstration by Breitman et alCitation59 that ATRA and 13-cis retinoic acid could induce differentiation in the HL-60 myeloid leukemia cell line. ATRA was subsequently shown to induce differentiation of leukemic cells in culture more potently than 13-cis retinoic acid.Citation60,Citation61 The PML-RARA fusion protein forms homodimers, recruits co-repressors and sequesters the normal RARA heterodimeric partner, retinoid X receptor-alpha. The complex binds to genes involved in myeloid differentiation, blocking their transcription. Retinoic acid in pharmacological doses binds to PML-RARA inducing a conformational change, allowing the dissociation of co-repressors and activating gene transcription and cellular differentiation.Citation62 Retinoic acid also induces PML-RARA degradation through recruitment of proteases (including caspases) and proteasomes; furthermore, this degradation pathway appears to be distinct to that required to induce differentiation.Citation63–Citation68

Following isolated case reports, Huang et alCitation69 published the successful treatment of APL with ATRA in 24 patients, with >90% CR and no exacerbation of coagulopathy or early death due to hemorrhage. The efficacy of ATRA was confirmed by Laurent Degos’ group in Paris.Citation70,Citation71 However, ATRA alone could not induce a prolonged remission as seen in the initial studies that demonstrated that despite maintenance therapy with ATRA or low-dose chemotherapy, the majority of patients relapsed within 6 months.Citation70,Citation72,Citation73

Researchers also noted a clinical syndrome caused by ATRA-induced differentiation of leukemic cells. Differentiation syndrome (DS), as it became known, can manifest with unexplained fever, hypotension, weight gain (>5 kg), respiratory distress, pulmonary infiltrates, pleural and/or pericardial effusions and renal failure.Citation74,Citation75 The pathogenesis of DS has not been well defined; the hypothesis derived from research in primary culture and using cell lines suggests a systemic inflammatory response driven by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, with endothelial damage, capillary leak and alterations in cellular adhesion molecule expression leading to tissue infiltration by leukemic cells and microcirculation occlusion.Citation76,Citation77 The risk of DS is greatest in patients who present with or develop a raised white cell count (WCC) with treatment. Thus, regimens that include the myelotoxic effects of chemotherapy taken concurrently with ATRA help reduce the risk of rising WCC and DS. The standard accepted management once DS is recognized is treatment with corticosteroids, eg, dexamethasone 10 mg twice daily intravenously (IV) until resolution and for at least 3 days.Citation78 The use of prophylactic steroid therapy during induction shows a beneficial reduction in the incidence of DS, although no randomized studies have been reported.Citation38,Citation39,Citation79–Citation81

Intensive anthracycline-based chemotherapy in combination with ATRA demonstrated excellent results in early non-randomized and later randomized trials. The prospective randomized European APL91 trial that compared three cycles of chemotherapy with or without ATRA was stopped early due to the significant improvement in event-free survival (EFS) in the ATRA therapy cohort.Citation82,Citation83 The EFS at 12 months in the ATRA-treated group was 79% compared to 50% in the chemotherapy-treated cohort (P=0.001), and after a 4-year follow-up, the EFS in the ATRA group was 63% compared to 17% in the chemotherapy-only cohort. The follow-up APL93 trial demonstrated a benefit to commencing chemotherapy simultaneously with ATRA as opposed to ATRA followed by sequential chemotherapy. The study also included a maintenance randomization and compared no maintenance, low-dose chemotherapy with 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and methotrexate, and ATRA 15 days every 3 months minus or plus low-dose chemotherapy. The rates of relapse at 2 years were 27%, 11%, 13% and 7.4%, respectively.Citation84

Subsequently, ATRA in combination with chemotherapy was investigated by multiple groups with CR rates between 72% and 95%.Citation85–Citation90 The Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) used an ATRA/idarubicin (AIDA) induction and added three cycles of consolidation containing idarubicin, cytarabine, etoposide, mitoxantrone and thioguanine. The resulting AIDA0493 protocol achieved a 95% CR rate, 2-year EFS of 79% and OS of 87%.Citation89,Citation90 The Spanish Programa Espãnol de Tratamientos en Hematología (PETHEMA) LPA96 trial successfully demonstrated that removing all non-anthracycline drugs from the consolidation phase after an AIDA-based induction did not significantly affect patient outcomes with a CR rate of 89%, 2-year EFS of 79% and OS of 82%.Citation85 Similarly, the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) APML3 trial used an AIDA induction backbone and an additional second cycle of idarubicin. The CR rate was 86%, and the importance of maintenance in this setting was shown by separate cohorts treated with or without maintenance, 4-year disease-free survival (DFS) 78.9% vs 46.9%, respectively.Citation91

Since the combined data from the AIDA0493 and LPA096 trials had identified no benefit from the use of non-anthracycline drugs during consolidation, a joint analysis was undertaken that identified the WCC and platelet count as reliable predictors of relapse, after achievement of a CR. This heralded the era of risk-adapted therapy with the so-called Sanz criteria ().Citation92

Table 1 Risk stratification in APL

Subsequently, risk-stratified trials based on an AIDA induction backbone demonstrated a benefit of ATRA in consolidation for all patients (LPA99 trial) and cytarabine in consolidation for high-risk patients (LPA2005 and AIDA2000 trials).Citation37,Citation93,Citation94 In the LPA2005 trial, high-risk patient treatment with cytarabine reduced the 3-year relapse rate from 26% to 11% (P=0.03) when compared to the results from the LPA99 trial, with an overall CR rate for all patients of 92.5%.Citation37,Citation94 Similarly, the AIDA2000 trial demonstrated that risk-adapted therapy in consolidation (ATRA for all patients, omission of non-anthracycline drugs for low/intermediate risk) resulted in all patients achieving better longer term outcomes. Low–intermediate risk patients suffered less toxicity and infection, while high-risk patients achieved a 6-year cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) of 9.3% compared to 49.7% (P<0.001) in the previous AIDA0493 trial.Citation93

The benefit of cytarabine in consolidation therapy for high-risk patients was also demonstrated by the French APL2000 trial, where a CR rate of 97.3% with a 7-year CIR of 7.1%, EFS of 82.2% and OS of 87.6% was achieved. The results in high-risk patients were comparable to those in low–intermediate risk patients who achieved a 7-year CIR of 12.9%.Citation95 A joint review of the results from the APL2000 and LPA99 trials confirmed a greater benefit for low–intermediate risk patients on an ATRA-idarubicin-based protocol and better survival for high-risk patients with more intense anthracycline and cytarabine consolidation.Citation96 It was proposed that because the AIDA protocol contained a higher cumulative dose of anthracycline or drugs with anthracycline equivalency, it generated better responses in lower risk patients.Citation97 In contrast, the UK MRC AML15 trial found no benefit to the inclusion of chemotherapy other than anthracyclines in the treatment of 285 patients who unsurprisingly experienced more toxicity and required an average of 19 more days in hospital.Citation98

The result of this progressive improvement in the understanding of patients’ risk and response was the European LeukaemiaNet recommendations for the management of APL. The expert panel advised induction based on an anthracycline/ATRA combination; a standard approach to consolidation should involve two to three cycles of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, intermediate- or high-dose cytarabine should be included in those younger patients with a WCC >10×109/L and that maintenance therapy should be used in patients treated with protocols in which maintenance has been shown to be of benefit.Citation78

The success achieved through treatment with ATRA-anthracycline-based protocols is unparalleled in other AML, but concern regarding the long-term risk of anthracycline and other chemotherapy exposure remains. Secondary cytogenetic abnormalities such as therapy-related myelodysplasia/AML have a reported incidence between 0.97% and 6.5% in French and Italian patient groups, respectively, and 2.2% at 6 years in all patients treated in the LPA96, LPA99 and LPA2005 trials who achieved CR.Citation99–Citation105 Anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity is also a concernCitation106,Citation107 as research has shown that patients treated on AIDA-based protocols developed subclinical but detectable diastolic dysfunction and regional wall motion abnormalities.Citation106 Recognized common acute side effects associated with ATRA therapy include fever, rash, headache and pseudotumor cerebri; the latter occurs more commonly in adolescents/children and may prompt dose reduction or cessation of ATRA in severe cases.Citation108 Long-term toxicity secondary to ATRA therapy has not been seen but requires ongoing review.

The arsenic era

Arsenic in various forms has been in use for >2000 years, by both Hippocrates in ancient Greece and in traditional Chinese medicine.Citation109,Citation110 Thomas Fowler’s eponymous solution of ATO was used as a tonic for the treatment of a variety of ailments and was also used to treat leukemia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.Citation111,Citation112

In 1973, researchers in Harbin province developed a solution of ATO and mercury chloride named “Ailing I” also known as “Ai-Lin I”, which they used to treat patients with acute and chronic leukemia. The successful treatment of patients with APL was reported initially in Chinese journals and was followed by a landmark publication in 1997, when researchers from Harbin and Shanghai described CR rates of 90% in patients with APL who had relapsed after ATRA and chemotherapy treatment and were treated with ATO as a single agent.Citation113 The proposed mechanism of action for ATO was the dose-dependent induction of apoptosis or differentiation.Citation114

Subsequent research has shown that arsenic’s therapeutic efficacy is due to its effect on the PML moiety of the PML-RARA fusion protein. The normal PML protein is of fundamental importance for the formation of so-called nuclear bodies (NBs), which allow recruitment and interaction of proteins through the posttranslational modifications of sumoylation and ubiquitination.Citation115 NBs are disrupted in APL with consequent loss of their tumor-suppressive activity. Arsenic binds to the PML component of PML-RARA through two cysteine residues in the B2 domain of PML protein, inducing their oxidation, leading to disulfide bond formation.Citation116,Citation117 The subsequent reformation of PML-containing NBs allows sumoylation of the PML/PML-RARA protein, concomitant recruitment of a SUMO-dependent ubiquitin ligase (RNF4) and polyubiquitination. The final step is the degradation of the PML moiety and its associated RARA partner by the proteasome.Citation118,Citation119 Additionally, arsenic induces the degradation of PML/PML-RARA through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that also produces oxidation of PML and formation of NBs. Since anthracyclines can also stimulate the production of ROS, there may a contributory role of anthracyclines in PML-RARA degradation.Citation120 Thus, in combination ATRA and ATO target the degradation of PML-RARA through distinct interactions with the RARA or PML moieties, respectively. The result is a synergistic destruction of the fusion protein and eradication of leukemia-initiating cells (LICs).Citation121,Citation122

The efficacy of ATO in the relapse setting was confirmed in a pilot study in New York, where 11 of 12 extensively pretreated patients achieved a CR. A subsequent multicenter study of 40 patients in first or second relapse utilized ATO for induction, consolidation and maintenance therapy. The CR rate was 85%, and the 18-month OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) were 66% and 56%, respectively.Citation123,Citation124 As the treatment of APL using ATRA-anthracycline-based protocols improved, ATO was shown to be an efficacious salvage treatment for relapse patients by numerous groups.Citation125–Citation130

The first successful trial of ATO in the treatment of newly diagnosed APL by Shen et al demonstrated that induction with ATO alone could induce CR in 90% of patients, whereas 95% of patients treated with ATRA alone or ATRA plus ATO achieved CR. There was a significantly shorter time to CR for patients treated with ATO/ATRA vs ATRA alone (25.5 vs 40.5 days, P=0.0003).Citation131 The protocol described by Shen et al contained moderately intensive consolidation therapy with three cycles of chemotherapy.Citation131 Longer term follow-up shows a 5-year DFS for the ATO/ATRA cohort of 94.8% and OS of 91.7%.Citation132 Another Chinese study reported on 90 patients also induced with either ATRA or ATO/ATRA who achieved CR rates of 90% vs 93%, respectively (P=0.56). The cohort of ATRA-induced patients was subsequently split and treated with traditional or ATO-containing consolidation/maintenance regimens. Replacing four of 10 cycles of chemotherapy in consolidation/maintenance with ATO increased the 3-year RFS from 72.4% to 92.9% (P=0.048). A similar RFS rate of 92.6% was achieved in ATO/ATRA-induced patients, who also received ATO-containing consolidation/maintenance.Citation133

The benefits of ATO use in consolidation were borne out by results of the North American Leukemia Intergroup C9710 study, where 90% of patients achieved a CR after ATRA and chemotherapy, and were then randomized to either receive additional ATO consolidation (two cycles of 0.15 mg/kg/day for 5 days for 5 weeks) or progress to a common ATRA/daunorubicin consolidation. The addition of ATO increased the 3-year EFS from 63% to 80% (P<0.0001) and 3-year DFS for all patients from 70% to 90% (P<0.0001). Crucially, consolidation with ATO significantly improved DFS for both low–intermediate (P<0.001) and high-risk patients (P<0.0001) compared to those not receiving ATO consolidation. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the 3-year DFS achieved using ATO consolidation in low–intermediate and high-risk cohorts (P=0.24).Citation36

Subsequently, three groups of researchers attempted to investigate whether ATO as monotherapy or in combination with minimal doses of chemotherapy could successfully treat patients diagnosed with APL. Two independent groups based in Tehran and Vellore reported the results of trials employing ATO as a monotherapy during induction, consolidation and maintenance, with chemotherapy only given in the event of leukocytosis or DS. The overall CR rate achieved was 86% in both trials with DFS in the Indian cohort of 87% at 3 years vs 63.7% in the Iranian cohort at 2 years.Citation134,Citation135 The poorer outcomes from the Tehran study were likely due to lower ATO exposure in the initial Iranian regimen, and despite adding additional consolidation cycles to their schedule after 2006, Iranian patients received less ATO within the first 6 months compared to the Vellore patients. Follow-up results at 5 years showed a DFS and an OS for the Vellore vs Tehran cohorts of 80% vs 67% and 74% vs 64%, respectively.Citation136,Citation137 Patients defined by the Vellore study criteria as good risk (WCC <5×109/L, platelets >20×109/L) had an EFS of 90% and OS of 100% compared to 60% and 63% in higher risk patients. Thus, ATO has impressive activity as a single agent but in higher risk patients, there still appeared a need for additional therapy. Furthermore, in combination with ATO, ATRA has been proposed to increase the expression of aquaglyceroporin 9, which facilitates increased ATO uptake.Citation138

The combination of ATRA, ATO and gemtuzumab ozogamicin for high-risk patients or those with rising WCCs was trialed by researchers at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin is a humanized anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody covalently conjugated with a cytotoxic anti-tumor agent calicheamicin. Over 6 years, 82 patients were treated with a CR rate of 90% and a 3-year estimated OS of 85%.Citation35,Citation139 The trial was small but demonstrated the potential benefits of the regimen, and the OS rates are similar to those of the LPA99 and C9710 trial of the same period without the use of traditional chemotherapeutic drugs or maintenance.Citation36,Citation94 However, high-risk patients and those aged >60 years still had poorer outcomes with OS rates of 69% and 73%, respectively.

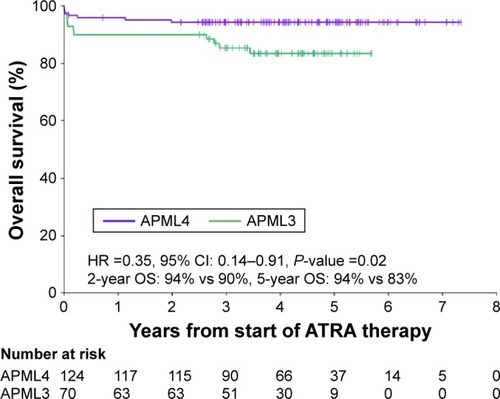

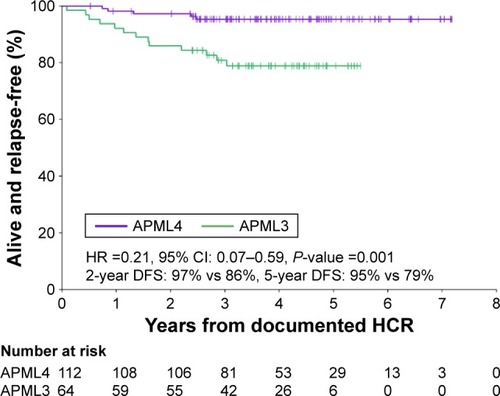

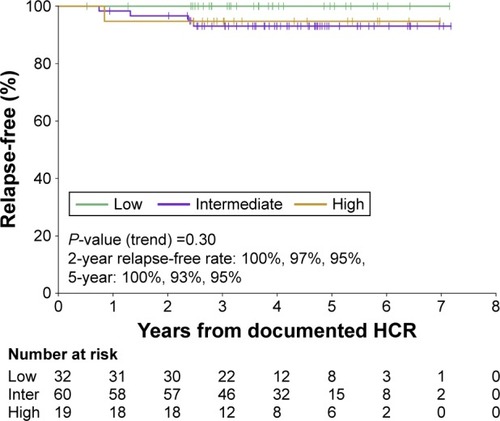

The ALLG APML4 trial rationalized the treatment of newly diagnosed patients to therapy with a combination of ATRA and ATO in combination with idarubicin in lower cumulative doses than those used in AIDA-based protocols. The aim of induction with ATRA, ATO and an anthracycline was to achieve the shortest time to remission and reduce the risks of hyperleukocytosis and DS. Aggressive hemostatic support and prophylactic prednisolone were included to reduce the rate of bleeding, DS and early death. The trial included consolidation therapy with ATRA/ATO and a 2-year maintenance regimen of ATRA, 6-MP and methotrexate proven to be of benefit in some previous studies.Citation84,Citation91 The early death rate was lower than in the APML3 trial, but not significantly so (3.2% vs 7.1%, P=0.29), while achieving a CR rate of 95% and a 2-year DFS of 97.5%.Citation38 After a median follow-up of 4.2 years, there was a significant improvement in 5-year OS (94%, P=0.02; ), DFS (95%, P=0.001; ) and EFS (90%, P=0.02) when compared to APML3.Citation41 In addition, high-risk patients in the APML4 trial appeared to benefit as the freedom from relapse was not significantly different between risk groups (). Furthermore, in high-risk patients, the 5-year CIR was only 5%, as compared to 11% at 3 years for the LPA2005 protocol, 9% at 6 years for AIDA2000 and 9.5% at 5 years for APL2000.Citation37,Citation80,Citation93,Citation96 These benefits were achieved without the addition of further moderate–high-dose chemotherapy during induction and/or consolidation, as utilized in the PETHEMA, GIMEMA and APL group trials and led to the incorporation of the APML4 protocol into the Canadian APL management guidelines and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for high-risk APL.Citation140,Citation141 Therefore, ATO + ATRA appeared to be an efficacious therapy for induction and consolidation in newly diagnosed APL, but randomized trials focusing on low/intermediate-risk vs high-risk APL were lacking.

Figure 1 Comparison of OS in the ALLG APML4 and ALLG APML3 trials.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; ALLG, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ATRA, all trans-retinoic acid.

Figure 2 Comparison of DFS in the ALLG APML4 and ALLG APML3 trials.

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; ALLG, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; HCR, hematological complete remission.

Figure 3 Estimated Kaplan–Meier curve for freedom from relapse from documented hematological CR in the APML4 trial, stratified by Sanz risk category.

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; HCR, hematological complete remission.

The APL0406 trial, a prospective, randomized, Phase III, multicenter study of low–intermediate risk patients by the GIMEMA, German–Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study and Study Alliance Leukemia groups tested whether ATO and ATRA induction and consolidation without maintenance therapy was non-inferior to the established AIDA2000 protocol. The impressive results included ATO/ATRA-treated patients achieving rates of CR, 2-year OS and 2-year EFS of 100%, 99% and 97%, respectively, compared to 95% (P=0.12), 91% (P=0.02) and 86% in the AIDA arm (P<0.001 for non-inferiority and P=0.02 for superiority).Citation39 The most recently published follow-up data showed that the 50-month EFS, OS and CIR were 97.3%, 99.2% and 1.9% in the ATO/ATRA cohort vs 80% (P<0.01), 92.6% (P=0.0073) and 13.9% (P=0.0013) in the AIDA cohort, respectively.Citation142 This study has helped define the current “Gold-Standard” treatment for low–intermediate risk APL.Citation140,Citation141

In the case of high-risk APL patients, the TUD-APOLLO-064 (NCT02688140) trial may clarify management by comparing an AIDA2000-based high-risk treatment arm (minus etoposide and thioguanine) with an APL0406-based treatment with two additional doses of idarubicin during induction.

The UK National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) AML17 trial randomized newly diagnosed APL patients to treatment with either AIDA induction and consolidation or ATRA combined with ATO given in a similar overall dose to that used in APL0406 but where more drug is given in the first week of the induction and consolidation cycles then less frequently in subsequent weeks. Fifty-seven high-risk patients were included (30 in the ATO/ATRA cohort), and gemtuzumab ozogamicin was also given to 28 of the 30 high-risk patients. The other two received additional idarubicin. The primary outcome of quality of life did not differ significantly between cohorts, but ATRA/ATO patients required less supportive care in the first two cycles of therapy as compared to the AIDA cohort.Citation40 In terms of secondary outcomes, CR was achieved in 89% of the AIDA cohort vs 94% for ATRA/ATO (P=0.18). In comparison between the ATRA/ATO and AIDA patients, there was significant improvement in 4-year EFS, 91% vs 70% (P=0.002), cumulative incidence of morphological relapse 1% vs 18% (P=0.0007), cumulative incidence of molecular relapse 0% vs 27% (P<0.0001) but not OS 93% vs 89% (P=0.25). The incidence of death in remission was very low 2% vs 1% in both ATRA/ATO and AIDA cohorts, respectively. There was a trend toward significant improvement in the 4-year EFS for high-risk patients treated with ATRA/ATO vs AIDA (87% vs 64%), but this did not reach significance (P=0.07).

provides a comparison of the most recent trials utilizing ATO in low–intermediate and high-risk APL.

Table 2 Results of recent ATO-inclusive trials

Arsenic side effects

ATO can induce myelosuppression, hepatic dysfunction, gastrointestinal disturbance, hyperleukocytosis and DS.Citation76,Citation114,Citation134,Citation135,Citation143 However, the most significant side effect requiring close monitoring is QT interval prolongation and the development of cardiac arrhythmia such as torsade de pointes. Electrocardiographic monitoring on a regular and frequent basis (twice weekly in our institution), measurement and replacement of electrolytes, especially potassium and magnesium, with the concurrent cessation of other drugs that can prolong the QT interval are recommended. Prolongation of the QT corrected for heart rate to >500 ms should prompt cessation of ATO. Long-term rates of secondary malignancies have not been extensively studied, but one short medium-term study found no increase in the incidence of secondary neoplasms in patients treated with ATRA-ATO.Citation144 Furthermore, no concerns regarding secondary malignancy were seen in long-term follow-up of a subset of the Shanghai cohort published recently.Citation145

Oral vs IV arsenic

Oral formulations of ATO have been used to consolidate CR in newly diagnosed or relapsed adult and pediatric patients.Citation146–Citation149 Recent trials into the use of oral tetra-arsenic tetra-sulfide (As4S4) also known as Realgar, in a formulation with Indigo naturalis, Salvia miltiorrhiza and radix pseudostellariae (RIF), have shown apparent equivalency to intravenous ATO in the treatment of APL. APL07, a multicenter, randomized trial of 242 patients, found that in the primary outcome of 2-year DFS, ATRA-RIF induction was non-inferior to ATRA-ATO with subsequent common chemotherapy consolidation, 98.1% vs 95.5% (non-inferior P<0.001). The CR rates were similar, 99.1% vs 97.2% (P=0.62) and 3-year OS of 99.1% vs 96.6% (P=0.18).Citation150 On longer term follow-up of 231 patients, the 7-year CIR, EFS and OS rates in the RIF vs ATO cohorts were not significantly different, and there was no significant difference in the CIR, EFS or OS between the high-risk and non-high-risk group.Citation151 Thus, Realgar-based therapy appears to be as efficacious as the ATO form. Researchers have proposed that while arsenic is known to target PML and induce its degradation via ubiquitination,Citation114 the active agents in Indigo naturalis and S. miltiorrhiza (indirubin and tanshinone II, respectively) facilitate the uptake of arsenic into leukemic cells in a manner similar to ATRA.Citation138,Citation152 The ALLG APML5 trial (ACTRN12616001022459p) will soon begin recruiting to investigate the bioavailability and performance of a novel oral ATO formulation vs IV ATO in combination with ATRA in consolidation.

The role of maintenance

The relative contribution of maintenance therapy is controversial with evidence from the ATRA-chemotherapy era for and against its use.Citation153–Citation156 However, a recent Cochrane meta-analysis could not identify a benefit from maintenance for OS despite an improvement in DFS.Citation157 Recent trials incorporating ATO have more clearly demonstrated the success achieved without maintenance in non-high-risk patients. The APL0406 trial demonstrated non-inferiority of ATRA-ATO without maintenance over ATRA-Ida with maintenance in non-high-risk patients.Citation39,Citation142 In addition, non-high-risk patients treated with ATRA-ATO in the UK AML17 trial achieved a 4-year OS of 95% with an overall 4-year cumulative incidence of morphological relapse of 1% in the ATRA-ATO arm despite no maintenance therapy.Citation40 In the APML4 trial,Citation38,Citation41 the lack of significant difference in the freedom from relapse between high- and non-high-risk patients appears to be the result of the ATRA-ATO-Ida induction and prolonged ATRA-ATO consolidation, not a historical maintenance regimen. In the era of oral ATRA-arsenic therapy, it may be that prolonged oral consolidation or maintenance therapy will prove useful in high-risk patients in combination with less chemotherapy intensive regimens.

FLT3 mutation

Mutations within FLT3, either ITDs or tyrosine kinase domain mutations, are present in 12%–38% and 2%–20% of cases of APL, respectively.Citation158,Citation159

The effects of FLT3 mutations on patient outcomes are inconsistent and appear dependent on the treatment regimen.Citation38,Citation91,Citation132,Citation159–Citation161 A meta-analysis by Beitinjaneh et al of patients treated predominantly with ATRA and chemotherapy identified lower rates of DFS and OS in patients with a FLT3-ITD. The risk ratio for 3-year DFS and OS in FLT3-ITD compared to wild type was 1.477, P=0.042 and 1.42, P=0.03, respectively.Citation159 Possession of a FLT3 mutation also appeared to increase the risk of induction death in adults and children.Citation158,Citation162 The addition of ATO to therapy appears to overcome the deleterious impact of a FLT3 mutation. The negative effect of FLT3 mutation on OS found in the ALLG APML3 trial was absent after the addition of ATO in induction and consolidation in the follow-up APML4 trial.Citation38,Citation91 Similarly, in the APL0406 trial cohort of low–intermediate risk patients, the presence of a FLT3 mutation was not associated with a poorer EFS when treated with ATO/ATRA. However, there was a trend toward a poorer EFS when treated without ATO in combination with ATRA.Citation163

In addition to FLT3 mutations, other pretreatment parameters associated with inferior prognosis include short PML-RARA isoforms (associated with bcr3 breakpoints) and increased expression of CD2, CD34 and CD56.Citation164 However, their relevance in the era of arsenic-based therapy has not been confirmed.

Early deaths

The unparalleled rates of survival in patients achieving a CR through current treatment protocols only help to highlight the continuing problem of early deaths. In contemporary trial publications from tertiary centers, the early death rates are <10%.Citation36,Citation37,Citation93,Citation132,Citation165 However, this is likely to underestimate the true rate as the trial data are vulnerable to various forms of selection bias, eg, failure to include diagnosed patients who succumb prior to therapy, restriction according to age or performance status or those who were never appropriately diagnosed in the first instance.Citation93,Citation166,Citation167 Retrospective analysis of patient outcomes outside the confines of a trial and population data identifies the rate of early death as between 17% and 29%.Citation8,Citation165,Citation167–Citation169

Coagulopathy and catastrophic bleeding, particularly within the brain and lungs, are the most common causes of early demise.Citation8,Citation167,Citation169–Citation171 There is a pathological activation of both pro-coagulant and fibrinolytic pathways in APL, and the contributions of tissue factor (TF), cancer pro-coagulant, Annexin II, plasminogen and thrombin activatable fibrinolytic inhibitor (TAFI) have been reviewed by both Breen et alCitation172 and Kwaan and Cull.Citation173 The pathological disturbance in the fibrinolytic pathway largely driven by increased Annexin II expression on abnormal promyelocytes is reversed by ATRA-induced differentiation.Citation174 However, pro-apoptotic treatment with chemotherapy and/or ATO will increase the levels of pro-coagulants, such as TF and cellular/membrane phospholipids. Therefore, treatment with ATRA should be started at the earliest suspicion of APL after clinical and morphological assessment, while awaiting confirmatory molecular or cytogenetic testing, and should be combined with aggressive hemostatic support programs using platelets and appropriate plasma components.Citation78 Recent reports detailed the use of a recombinant form of the thrombin inhibitor, thrombomodulin, in the treatment of APL-associated coagulopathy.Citation175–Citation177 The thrombin–thrombomodulin complex in association with plasmin activates TAFI, and thereby inhibits fibrinolysis.Citation178

The simplest and most powerful intervention shown to reduce the early death rate is education to both improve early identification of patients with APL and advocate for urgent initiation of therapy in a manner analogous to the emphasis on timely treatment of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Programs in developing countries to improve the treatment of patients using education, international collaboration, support and specific committees tasked with improving drug access and early initiation have driven dramatic improvements in patient survival.Citation179

Pediatric patients

There is an increased incidence of the microgranular variant (M3v) of APL in children, with associated leukocytosis and greater risk of coagulopathy and/or DS.Citation180 The treatment of children with APL has mirrored the developments made in adult therapy, and currently accepted protocols are based on research by the APL, GIMEMA, PETHEMA and German–Austrian–Swiss groups. Combinations of ATRA and chemotherapy help to achieve CR and 5-year OS rates between 92%–95% and 87%–90%, respectively.Citation181–Citation185 Protocol modifications in the pediatric population include the reduction of ATRA dose to 25 mg/m2, which helps to reduce the severity of side effects including headaches and pseudotumor cerebri, while achieving similar results to 45 mg/m2.Citation78,Citation184–Citation187 Independent studies by German and Japanese investigators using ATRA throughout induction, consolidation and maintenance and utilizing anthracycline and high-dose cytarabine in consolidation have shown similar OS rates. Creutzig et alCitation188 reported an OS of 89% at 5 years for pediatric patients in consecutive AML–Berlin/Frankfurt/Muenster trials. Imaizumi et alCitation189 reported that patients in the AML99-M3 study achieved an OS of 91% at 7 years.

ATO used as monotherapy for induction, consolidation and maintenance treatment of 11 children with microgranular APL in Vellore induced a CR in 91% with 30-month OS of 91% and RFS of 81%.Citation190 Similarly, researchers in China treated 19 children (including seven high-risk patients) with single-agent ATO for induction of remission and 3 years post-remission therapy. The CR, 5-year OS and EFS rates were 89.5%, 83.9% and 72.7%, respectively.Citation191 Another single-center analysis compared ATRA vs ATRA-ATO induction with the use of ATRA in consolidation for all children and an additional 28-day cycle of ATO in consolidation for the experimental arm. All children also received extensive consolidation chemotherapy. There was a significant improvement in survival with the inclusion of ATO with a 6.25-year EFS, DFS and OS for ATRA vs ATRA-ATO of 70.4% vs 92.5% (P=0.021), 76.4% vs 97.1% (P=0.012) and 70.4% vs 95.3% (P=0.007), respectively.Citation192

Therefore, progress has been made toward the introduction of ATRA-arsenic in the pediatric population, but risk-adapted trials to investigate rationalized chemotherapy are lacking. The Children’s Oncology Group Phase III, multicenter AAML0631 and AAML1331 trials (NCT00866918 and NCT02339740) are currently underway and aim to investigate risk-adapted and arsenic-based strategies in children.

Pregnancy

The management of pregnant patients with APL has been discussed in the European LeukemiaNet recommendations and most recently and succinctly by Milojkovic and Apperley.Citation78,Citation193 In summary, the management of APL in the first trimester rests on the decision on whether an elective termination is chosen as this will allow the initiation of standard ATRA-chemotherapy or ATRA-ATO-based therapy that is otherwise contraindicated. Should the patient elect to continue the pregnancy, then ATRA is excluded in the first trimester because of the risk of fetal malformations.Citation193 Arsenic therapy is not possible at any time in pregnancy due to its embryotoxicity.Citation194,Citation195 Treatment with daunorubicin is recommended, given its lower capacity to transfer across the placenta, lower solubility in lipids compared to idarubicin and shorter half-life. However, there remains an increased risk of abortion, premature labor, neonatal neutropenia and low birth weight.Citation194 Treatment after the second trimester can include the use of ATRA in combination with daunorubicin or as monotherapy, although there is an associated risk of ATRA resistance, short remission and DS in newly diagnosed patients.Citation71–Citation73,Citation196 Similarly, treatment with daunorubicin alone in newly diagnosed patients carries the risk of the exacerbation of the APL-associated coagulopathy and hemorrhage. Combination daunorubicin-ATRA therapy would logically achieve the best outcomes for the patient (and indirectly the fetus) but close monitoring of the potentially toxic side effects is essential including cardiac toxicity associated with ATRA.Citation78,Citation197,Citation198 In all patients, there is a need for comprehensive multi-disciplinary care involving an obstetrician, a fetal medicine specialist and a hematologist.

Conclusion

The paradigm of differentiation therapy constructed on the discovery and success with ATRA has evolved with the introduction of ATO and the recognition of the synergistic destruction of the PML-RARA protein. The serendipitous discovery of two agents that directly target the PML-RARA mutation that drives disease has led to unparalleled success in patient cure, through better eradication of LICs. The benefits of risk-adapted therapy with ATRA-chemotherapy and now ATRA-ATO without chemotherapy have been established for low–intermediate risk patients. Recent research appears to show that in high-risk patients, ATRA-ATO may overcome the increased relapse risk provided they are combined with rationally reduced use of chemotherapy or gemtuzumab ozogamicin, and randomized controlled trials are underway that will hopefully confirm this. Maintenance therapy appears dispensable in low-risk patients treated with ATRA-ATO, but this has not been defined in the high-risk cohort. There is significant progress to be made in the early death rate, particularly in developing countries, and the increasing availability of oral ATRA therapy may facilitate this. Examples of currently recommended treatment regimens for APL are summarized in .

Table 3 Commonly employed current treatment regimens in APL, stratified by risk category

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HillestadLKAcute promyelocytic leukemiaActa Med Scand1957159318919413508085

- PisciottaAVSchulzEJFibrinolytic purpura in acute leukemiaAm J Med195519582482813268484

- CooperbergAANeimanGMAFibrinogenopenia and fibrinolysis in acute myelogenous leukemiaAnn Intern Med195542370671114350491

- CroizatPFavre-GillyJLes aspects du syndrome hémorragique des leucémies; à propos de 12 cas de thrombocytopénie et d’un cas de fibrinopénie [Aspects of the leukemia hemorrhagic syndrome; in 12 cases of thrombocytopenia and one case of fibrinopenia]Sang1949207417421 French15403133

- RizakEDie Fibrinopenie [The Fibrinopenia]Z Klin Med1935128605 German

- BernardJMatheGBoulayJCeoardBChomeJLa leucemie aiguë à promyelocytes. Étude portant sur vingt observations [Acute promyelocytic leukemia: a study made on 20 cases]Schweiz Med Wochenschr195989604608 French13799642

- GrimwadeDHillsRKMoormanAVNational Cancer Research Institute Adult Leukaemia Working GroupRefinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trialsBlood2010116335436520385793

- LehmannSRavnACarlssonLContinuing high early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia: a population-based report from the Swedish Adult Acute Leukemia RegistryLeukemia20112571128113421502956

- RegoEMJácomoRHEpidemiology and treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia in Latin AmericaMediterr J Hematol Infect Dis201131e201104922110899

- DouerDThe epidemiology of acute promyelocytic leukaemiaBest Prac Res Clin Haematol2003163357367

- BennettJMCatovskyDDanielM-TProposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias French-American-British (FAB) Co-operative GroupBr J Haematol1976334451458188440

- BennettJMCatovskyDDanielMTA variant form of hypergranular promyelocytic leukaemia (M3)Br J Haematol19804411691706929699

- RowleyJDGolombHMDoughertyC15/17 translocation, a consistent chromosomal change in acute promyelocytic leukaemiaLancet197718010549550

- TestaJGolombHRowleyJVardimanJSweetDJHypergranular promyelocytic leukemia (APL): cytogenetic and ultrastructural specificityBlood1978522272280276386

- SwerdlowSHCEHarrisLJaffeESWHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid TissueLyonThe International Agency for Research on Cancer2008

- ArberDAOraziAHasserjianRThe 2016 revision to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemiaBlood2016127202391240527069254

- MadanVShyamsunderPHanLComprehensive mutational analysis of primary and relapse acute promyelocytic leukemiaLeukemia2016301672168127063598

- NCI (NIH) [webpage on the Internet]SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)NIH (online)2016 Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/amyl.htmlAccessed November 3, 2016

- AppelbaumFRGundackerHHeadDRAge and acute myeloid leukemiaBlood200610793481348516455952

- PulteDGondosABrennerHImprovements in survival of adults diagnosed with acute myeloblastic leukemia in the early 21st centuryHaematologica200893459460018322250

- DöhnerHWeisdorfDJBloomfieldCDAcute myeloid leukemiaN Engl J Med20153731136115226376137

- GrimwadeDWalkerHOliverFThe importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trialBlood199892232223339746770

- SlovakMLKopeckyKJCassilethPAKaryotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group studyBlood200096134075408311110676

- ByrdJCMrozekKDodgeRKCancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461)Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461)Blood2002100134325433612393746

- SchnittgerSSchochCKernWNucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotypeBlood2005106123733373916076867

- ThiedeCKochSCreutzigEPrevalence and prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in 1485 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML)Blood2006107104011402016455956

- MrózekKMarcucciGPaschkaPWhitmanSPBloomfieldCDClinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification?Blood2007109243144816960150

- SchlenkRFDöhnerKKrauterJGerman-Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study GroupMutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemiaN Engl J Med2008358181909191818450602

- HouHALinLIChenCYTienHFReply to ‘Heterogeneity within AML with CEBPA mutations; only CEBPA double mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations are associated with favorable prognosis’Br J Cancer2009101473874019623175

- PabstTEyholzerMFosJMuellerBUHeterogeneity within AML with CEBPA mutations; only CEBPA double mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations are associated with favourable prognosisBr J Cancer200910081343134619277035

- WoutersBJLöwenbergBErpelinck-VerschuerenCAJvan PuttenWLJValkPJMDelwelRDouble CEBPA mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations, define a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with a distinctive gene expression profile that is uniquely associated with a favorable outcomeBlood20091133088309119171880

- DufourASchneiderFMetzelerKHAcute myeloid leukemia with biallelic CEBPA gene mutations and normal karyotype represents a distinct genetic entity associated with a favorable clinical outcomeJ Clin Oncol201028457057720038735

- GreenCLKooKKHillsRKBurnettAKLinchDCGaleREPrognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in a large cohort of younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: impact of double CEBPA mutations and the interaction with FLT3 and NPM1 mutationsJ Clin Oncol201028162739274720439648

- TaskesenEBullingerLCorbaciogluAPrognostic impact, concurrent genetic mutations, and gene expression features of AML with CEBPA mutations in a cohort of 1182 cytogenetically normal AML patients: further evidence for CEBPA double mutant AML as a distinctive disease entityBlood201111782469247521177436

- EsteyEGarcia-ManeroGFerrajoliAUse of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide as an alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood200610793469347316373661

- PowellBLMoserBStockWArsenic trioxide improves event-free and overall survival for adults with acute promyelocytic leukemia: North American Leukemia Intergroup Study C9710Blood2010116193751375720705755

- SanzMAMontesinosPRayonCPETHEMA and HOVON GroupsRisk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia based on all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline with addition of cytarabine in consolidation therapy for high-risk patients: further improvements in treatment outcomeBlood2010115255137514620393132

- IlandHJBradstockKSuppleSGAustralasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma GroupAll-trans-retinoic acid, idarubicin, and IV arsenic trioxide as initial therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML4)Blood201212081570158022715121

- Lo-CocoFAvvisatiGVignettiMGruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto, the German–Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group, and Study Alliance LeukemiaRetinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemiaN Engl J Med2013369211112123841729

- BurnettAKRussellNHHillsRKthe UK National Cancer Research Institute Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Working GroupArsenic trioxide and all-trans retinoic acid treatment for acute promyelocytic leukaemia in all risk groups (AML17): results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trialLancet Oncol201516131295130526384238

- IlandHJCollinsMBradstockKAustralasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma GroupUse of arsenic trioxide in remission induction and consolidation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukaemia in the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group (ALLG) APML4 study: a non-randomised phase 2 trialLancet Haematol201529e357e36626685769

- Lo-CocoFDi DonatoLSchlenkRFTargeted therapy alone for acute promyelocytic leukemiaN Engl J Med2016374121197119827007970

- DrapkinRLGeeTSDowlingMDProphylactic heparin therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemiaCancer197841624842490274995

- DidisheimPTromboldJSVandervoortRLEMibashanRSAcute promyelocytic leukemia with fibrinogen and factor V deficienciesBlood196423671772814161406

- RosenthalRLAcute promyelocytic leukemia associated with hypofibrinogenemiaBlood196321449550813974993

- BernardJWeilMBoironMJacquillatCFlandrinGGemonM-FAcute promyelocytic leukemia: results of treatment by daunorubicinBlood19734144894964510926

- CollinsAJBloomfieldCDPetersonBAMcKennaRWEdsonJAcute promyelocytic leukemia: management of the coagulopathy during daunorubicin-prednisone remission inductionArch Intern Med19781381116771680281191

- MartyMGanemGFischerJLeucemie aigue promyelocytaire; etude retrospective de 119 malades traits par Daunorubicine [Acute promyelocytic leukemia: retrospective study of 119 patients treated with daunorubicin]Nouv Rev Fr Hematol1984266371378 French6597407

- CordonnierCVernantJPBrunBAcute promyelocytic leukemia in 57 previously untreated patientsCancer198555118253855265

- PettiMCAvvisatiGAmadoriSAcute promyelocytic leukemia: clinical aspects and results of treatment in 62 patientsHaematologica19877221511553114070

- SanzMAJarqueIMartínGAcute promyelocytic leukemia. Therapy results and prognostic factorsCancer19886117133422032

- CunninghamIGeeTReichLKempinSNavalAClarksonBAcute promyelocytic leukemia: treatment results during a decade at Memorial HospitalBlood1989735111611222930837

- AvvisatiGMandelliFPettiMCIdarubicin (4-demethoxydauno-rubicin) as single agent for remission induction of previously untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia: a pilot study of the Italian cooperative group GIMEMAEur J Haematol19904442572602188854

- FenauxPTertianGCastaigneSA randomized trial of amsacrine and rubidazone in 39 patients with acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Clin Oncol199199155615611805818

- FenauxPPolletJPVandenbossche-SimonLTreatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a report of 70 casesLeuk Lymphoma19914423924827463043

- KantarjianHMKeatingMJWaltersRSAcute promyelocytic leukemiaAm J Med19868057897973458366

- HeadDKopeckyKJWeickJEffect of aggressive daunomycin therapy on survival in acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood1995865171717287655004

- AvvisatiGPettiMCLo-CocoFGIMEMA (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto) Italian Cooperative GroupInduction therapy with idarubicin alone significantly influences event-free survival duration in patients with newly diagnosed hypergranular acute promyelocytic leukemia: final results of the GIMEMA randomized study LAP 0389 with 7 years of minimal follow-upBlood200210093141314612384411

- BreitmanTRSelonickSECollinsSJInduction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acidProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1980775293629406930676

- BreitmanTRCollinsSJKeeneBRTerminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemic cells in primary culture in response to retinoic acidBlood1981576100010046939451

- ChomienneCBalleriniPBalitrandNAll-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemias. II. In vitro studies: structure-function relationshipBlood1990769171017172224120

- WangZ-YChenZAcute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curableBlood200811152505251518299451

- RaelsonJNerviCRosenauerAThe PML/RAR alpha oncoprotein is a direct molecular target of retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia cellsBlood1996888282628328874178

- YoshidaHKitamuraKTanakaKAccelerated degradation of PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML-RARA) oncoprotein by all-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia: possible role of the proteasome pathwayCancer Res19965613294529488674046

- NerviCFerraraFFFanelliMCaspases mediate retinoic acid-induced degradation of the acute promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARalpha fusion proteinBlood1998927224422519746761

- ZhuJGianniMKopfERetinoic acid induces proteasome-dependent degradation of retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARalpha) and oncogenic RARalpha fusion proteinsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19999626148071481210611294

- NasrRGuilleminMCFerhiOEradication of acute promyelocytic leukemia-initiating cells through PML-RARA degradationNat Med200814121333134219029980

- LaneAALeyTJNeutrophil elastase cleaves PML-RARalpha and is important for the development of acute promyelocytic leukemia in miceCell2003115330531814636558

- HuangMYeYChenSUse of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood19887225675723165295

- DegosLChomienneCDanielMTTreatment of first relapse in acute promyelocytic leukaemia with all-trans retinoic acidLancet1990336872814401441

- CastaigneSChomienneCDanielMTAll-trans retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. I. Clinical resultsBlood1990769170417092224119

- WarrellRPJrMaslakPEardleyAHellerGMillerWHJrFrankelSRTreatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans retinoic acid: an update of the New York experienceLeukemia1994869299338207986

- ChenZXXueYQZhangRA clinical and experimental study on all-trans retinoic acid-treated acute promyelocytic leukemia patientsBlood1991786141314191884013

- FrankelSREardleyALauwersGWeissMWarrellRPJrThe “retinoic acid syndrome” in acute promyelocytic leukemiaAnn Intern Med199211742922961637024

- De BottonSDombretHSanzMIncidence, clinical features, and outcome of all trans-retinoic acid syndrome in 413 cases of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European APL GroupBlood1998928271227189763554

- LuesinkMPenningsJLAWissinkWMChemokine induction by all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide in acute promyelocytic leukemia: triggering the differentiation syndromeBlood2009114275512552119828696

- SanzMAMontesinosPHow we prevent and treat differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood2014123182777278224627526

- SanzMAGrimwadeDTallmanMSManagement of acute promyelocytic leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNetBlood200911391875189118812465

- WileyJSFirkinFCReduction of pulmonary toxicity by prednisolone prophylaxis during all-trans retinoic acid treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Australian Leukaemia Study GroupLeukemia1995957747787769839

- KelaidiCChevretSDe BottonSImproved outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia with high WBC counts over the last 15 years: The European APL Group ExperienceJ Clin Oncol200927162668267619414681

- MontesinosPBerguaJMVellengaEDifferentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline chemotherapy: characteristics, outcome, and prognostic factorsBlood2009113477578318945964

- FenauxPChevretSGuerciALong-term follow-up confirms the benefit of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. European APL groupLeukemia20001481371137710942231

- FenauxPLe DeleyMCCastaigneSEffect of all transretinoic acid in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Results of a multicenter randomized trial. European APL 91 GroupBlood19938211324132498241496

- FenauxPChastangCChevretSA randomized comparison of all transretinoic acid (ATRA) followed by chemotherapy and ATRA plus chemotherapy and the role of maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood19999441192120010438706

- SanzMAMartıńGRayónCA modified AIDA protocol with anthracycline-based consolidation results in high antileukemic efficacy and reduced toxicity in newly diagnosed PML/RARα-positive acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood19999493015302110556184

- BurnettAKGrimwadeDSolomonEWheatleyKGoldstoneAHPresenting white blood cell count and kinetics of molecular remission predict prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid: result of the randomized MRC trialBlood199993124131414310361110

- AsouNAdachiKTamuraJAnalysis of prognostic factors in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy. Japan Adult Leukemia Study GroupJ Clin Oncol199816178859440726

- TallmanMSAndersenJWSchifferCAAll-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. [Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 1997;337(22):1639]N Engl J Med199733715102110289321529

- MandelliFDiverioDAvvisatiGMolecular remission in PML/RARα-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia by combined all-trans retinoic acid and idarubicin (AIDA) therapyBlood1997903101410219242531

- AvvisatiGLo CocoFDiverioDAIDA (all-trans retinoic acid + idarubicin) in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: a Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) pilot studyBlood1996884139013988695858

- IlandHBradstockKSeymourJAustralasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma GroupResults of the APML3 trial incorporating all-trans-retinoic acid and idarubicin in both induction and consolidation as initial therapy for patients with acute promyelocytic leukemiaHaematologica201297222723421993673

- SanzMACocoFLMartínGDefinition of relapse risk and role of nonanthracycline drugs for consolidation in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: a joint study of the PETHEMA and GIMEMA cooperative groupsBlood20009641247125310942364

- Lo-CocoFAvvisatiGVignettiMItalian GIMEMA Cooperative GroupFront-line treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with AIDA induction followed by risk-adapted consolidation for adults younger than 61 years: results of the AIDA-2000 trial of the GIMEMA GroupBlood2010116173171317920644121

- SanzMAMartinGGonzalezMRisk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: a multicenter study by the PETHEMA groupBlood200410341237124314576047

- AdèsLChevretSRaffouxEEuropean APL GroupLong-term follow-up of European APL 2000 trial, evaluating the role of cytarabine combined with ATRA and Daunorubicin in the treatment of nonelderly APL patientsAm J Hematol201388755655923564205

- AdesLSanzMAChevretSTreatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): a comparison of French-Belgian-Swiss and PETHEMA resultsBlood200811131078108417975017

- SanzMAMartinGLo CocoFChoice of chemotherapy in induction, consolidation and maintenance in acute promyelocytic leukaemiaBest Prac Clin Haematol2003163433451

- BurnettAKHillsRKGrimwadeDUnited Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute Acute Myeloid Leukaemia SubgroupInclusion of chemotherapy in addition to anthracycline in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukaemia does not improve outcomes: results of the MRC AML15 trialLeukemia201327484385123222369

- MontesinosPGonzalezJDGonzalezJTherapy-related myeloid neoplasms in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans-retinoic acid and anthracycline-based chemotherapyJ Clin Oncol201028243872387920625122

- BatziosCHayesLAHeSZSecondary clonal cytogenetic abnormalities following successful treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. [Erratum appears in Am J Hematol. 2010;85(7):550]Am J Hematol2009841171571919806661

- LobeIRigal-HuguetFVekhoffAEuropean APL Group ExperienceMyelodysplastic syndrome after acute promyelocytic leukemia: the European APL group experienceLeukemia20031781600160412886249

- ZompiSViguieFTherapy-related acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia after successful treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemiaLeuk Lymphoma200243227528011999558

- LatagliataRPettiMCFenuSTherapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome-acute myelogenous leukemia in patients treated for acute promyelocytic leukemia: an emerging problemBlood200299382282411806982

- Garcia-ManeroGKantarjianHKornblauSEsteyETherapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)Leukemia20021691888

- AndersenMKPedersen-BjergaardJTherapy-related MDS and AML in acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood20021001928193012211197

- PellicoriPCalicchiaALococoFCiminoGTorromeoCSubclinical anthracycline cardiotoxicity in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia in long-term remission after the AIDA protocolCongest Heart Fail201218421722122809260

- ThomasXLeQHFiereDAnthracycline-related toxicity requiring cardiac transplantation in long-term disease-free survivors with acute promyelocytic leukemiaAnn Hematol200281950450712373350

- AvvisatiGNewly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemiaMediterr J Hematol Infect Dis201131e201106422220261

- ByrnsMCPenningTMChapter 67 Environmental toxicology: carcinogens and heavy metalsBruntonLLChabnerBAKnollmannBCGoodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12eNew York, NYThe McGraw-Hill Companies2011

- ChenSJZhouGBZhangXWMaoJHde TheHChenZFrom an old remedy to a magic bullet: molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of arsenic in fighting leukemiaBlood2011117246425643721422471

- ForknerCEScottTArsenic as a therapeutic agent in chronic myelogenous leukemia: preliminary reportJ Am Med Assoc193197135

- KwongYLToddDDelicious poison: arsenic trioxide for the treatment of leukemiaBlood1997899348734879129058

- ShenZXChenGQNiJHUse of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): II. Clinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics in relapsed patientsBlood1997899335433609129042

- ChenGQShiXGTangWUse of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): I. As2O3 exerts dose-dependent dual effects on APL cellsBlood1997899334533539129041

- de TheHLe BrasMLallemand-BreitenbachVThe cell biology of disease: acute promyelocytic leukemia, arsenic, and PML bodiesJ Cell Biol20121981112122778276

- JeanneMLallemand-BreitenbachVFerhiOPML/RARA oxidation and arsenic binding initiate the antileukemia response of As2O3Cancer Cell2010181889820609355

- ZhangX-WYanX-JZhouZ-RArsenic trioxide controls the fate of the PML-RARalpha oncoprotein by directly binding PML.[Erratum appears in Science. 2010;328(5981):974]Science2010328597524024320378816

- Lallemand-BreitenbachVJeanneMBenhendaSArsenic degrades PML or PML-RARalpha through a SUMO-triggered RNF4/ubiquitin-mediated pathwayNat Cell Biol200810554755518408733

- TathamMHGeoffroyM-CShenLRNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradationNat Cell Biol200810553854618408734

- dos SantosGAKatsLPandolfiPPSynergy against PML-RARa: targeting transcription, proteolysis, differentiation, and self-renewal in acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Exp Med2013210132793280224344243

- Lallemand-BreitenbachVGuilleminMCJaninARetinoic acid and arsenic synergize to eradicate leukemic cells in a mouse model of acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Exp Med199918971043105210190895

- RegoEMHeLZWarrellRPJrWangZGPandolfiPPRetinoic acid (RA) and As2O3 treatment in transgenic models of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) unravel the distinct nature of the leukemogenic process induced by the PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha oncoproteinsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A20009718101731017810954752

- SoignetSLFrankelSRDouerDUnited States multicenter study of arsenic trioxide in relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Clin Oncol200119183852386011559723

- SoignetSLMaslakPWangZGComplete remission after treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxideN Engl J Med199833919134113489801394

- AuWYLieAKWChimCSArsenic trioxide in comparison with chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of relapsed acute promyelocytic leukaemiaAnn Oncol200314575275712702530

- LazoGKantarjianHEsteyEThomasDO’BrienSCortesJUse of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: the M. D. Anderson experienceCancer20039792218222412712474

- NiuCYanHYuTStudies on treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide: remission induction, follow-up, and molecular monitoring in 11 newly diagnosed and 47 relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia patientsBlood199994103315332410552940

- RaffouxERousselotPPouponJCombined treatment with arsenic trioxide and all-trans-retinoic acid in patients with relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Clin Oncol200321122326233412805334

- ShigenoKNaitoKSaharaNArsenic trioxide therapy in relapsed or refractory Japanese patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: updated outcomes of the phase II study and postremission therapiesInt J Hematol200582322422916207595

- ThomasXPigneuxARaffouxEHuguetFCaillotDFenauxPSuperiority of an arsenic trioxide-based regimen over a historic control combining all-trans retinoic acid plus intensive chemotherapy in the treatment of relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemiaHaematologica200691799699716757416

- ShenZ-XShiZ-ZFangJAll-trans retinoic acid/As2O3 combination yields a high quality remission and survival in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemiaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2004101155328533515044693

- HuJLiuY-FWuC-FLong-term efficacy and safety of all-trans retinoic acid/arsenic trioxide-based therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemiaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200910693342334719225113

- DaiC-WZhangG-SShenJ-KUse of all-trans retinoic acid in combination with arsenic trioxide for remission induction in patients with newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia and for consolidation/maintenance in CR patients. [Erratum appears in Acta Haematol. 2009;121(4):243]Acta Haematol200912111819246888

- MathewsVGeorgeBLakshmiKMSingle-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: durable remissions with minimal toxicityBlood200610772627263216352810

- GhavamzadehAAlimoghaddamKGhaffariSHTreatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with arsenic trioxide without ATRA and/or chemotherapyAnn Oncol200617113113416227315

- GhavamzadehAAlimoghaddamKRostamiSPhase II study of single-agent arsenic trioxide for the front-line therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemiaJ Clin Oncol201129202753275721646615

- MathewsVGeorgeBChendamaraiESingle-agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: long-term follow-up dataJ Clin Oncol201028243866387120644086

- LeungJPangAYuenW-HKwongY-LTseEWCRelationship of expression of aquaglyceroporin 9 with arsenic uptake and sensitivity in leukemia cellsBlood2007109274074616968895

- RavandiFEsteyEJonesDEffective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicinJ Clin Oncol200927450451019075265

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network [homepage on the Internet]Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology2016 Available from: http://www.nccn.org/Accessed January 27, 2017

- SeftelMDBarnettMJCoubanSA Canadian consensus on the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia in adultsCurr Oncol201421523425025302032

- PlatzbeckerUAvvisatiGCicconiLImproved outcomes with retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide compared with retinoic acid and chemotherapy in non–high-risk acute promyelocytic leukemia: final results of the randomized Italian-German APL0406 trialJ Clin Oncol201735660561227400939

- IlandHJSeymourJFRole of arsenic trioxide in acute promyelocytic leukemiaCurr Treat Options Oncol201314217018423322117

- EghtedarARodriguezIKantarjianHIncidence of secondary neoplasms in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid plus chemotherapy or with all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxideLeuk Lymphoma20155651342134525120050

- ZhuHHuJChenLThe 12-year follow-up of survival, chronic adverse effects, and retention of arsenic in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood20161281525152827402972

- FirkinFOral administration of arsenic trioxide in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukaemia and accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukaemia: an Australian single-centre studyIntern Med J201242894895222906029

- AuW-YKumanaCRLeeHKKOral arsenic trioxide-based maintenance regimens for first complete remission of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a 10-year follow-up studyBlood2011118256535654321998212

- SiuC-WAuW-YYungCEffects of oral arsenic trioxide therapy on QT intervals in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: implications for long-term cardiac safetyBlood2006108110310616514059

- AuWYLiC-KLeeVOral arsenic trioxide for relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia in pediatric patientsPediatr Blood Cancer201258463063221898784

- ZhuH-HWuD-PJinJOral tetra-arsenic tetra-sulfide formula versus intravenous arsenic trioxide as first-line treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a multicenter randomized controlled trialJ Clin Oncol201331334215422124127444

- ZhuH-HWuD-PJinJLong-term survival of acute promyelocytic leukaemia patients treated with arsenic and retinoic acidBr J Haematol2016174582082227545413

- WangLZhouG-BLiuPDissection of mechanisms of Chinese medicinal formula Realgar-Indigo naturalis as an effective treatment for promyelocytic leukemiaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2008105124826483118344322

- AvvisatiGLo-CocoFPaoloniFPGIMEMA, AIEOP, and EORTC Cooperative GroupsAIDA 0493 protocol for newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: very long-term results and role of maintenanceBlood2011117184716472521385856

- AdesLGuerciARaffouxEEuropean APL GroupVery long-term outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy: the European APL Group experienceBlood201011591690169620018913

- AsouNKishimotoYKiyoiHJapan Adult Leukemia Study GroupA randomized study with or without intensified maintenance chemotherapy in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia who have become negative for PML-RARalpha transcript after consolidation therapy: the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group (JALSG) APL97 studyBlood20071101596617374742

- TallmanMSAndersenJWSchifferCAAll-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia: long-term outcome and prognostic factor analysis from the North American Intergroup protocolBlood2002100134298430212393590

- MuchtarEVidalLRamRGafter-GviliAShpilbergORaananiPThe role of maintenance therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia in the first complete remissionCochrane Database Syst Rev20133CD00959423543579

- GaleREHillsRPizzeyARNCRI Adult Leukaemia Working PartyRelationship between FLT3 mutation status, biologic characteristics, and response to targeted therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemiaBlood2005106123768377616105978

- BeitinjanehAJangSRoukozHMajhailNSPrognostic significance of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and tyrosine kinase domain mutations in acute promyelocytic leukemia: a systematic reviewLeuk Res201034783183620096459

- BarraganEMontesinosPCamosMPETHEMA; HOVON GroupsPrognostic value of FLT3 mutations in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapyHaematologica201196101470147721685470

- SchnittgerSBacherUHaferlachCKernWAlpermannTHaferlachTClinical impact of FLT3 mutation load in acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17)/PML-RARAHaematologica201196121799180721859732

- KutnyMAMoserBKLaumannKFLT3 mutation status is a predictor of early death in pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology GroupPediatr Blood Cancer201259466266722378655

- CicconiLDivonaMCiardiCPML-RARα kinetics and impact of FLT3-ITD mutations in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with ATRA and ATO or ATRA and chemotherapyLeukemia2016301987199227133819

- TestaULo-CocoFPrognostic factors in acute promyelocytic leukemia: strategies to define high-risk patientsAnn Hematol201695567368026920716

- LengfelderEHanfsteinBHaferlachCGerman Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group (AMLCG)Outcome of elderly patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: results of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative GroupAnn Hematol2013921415223090499

- LengfelderEHaferlachCSausseleSGerman AML Cooperative GroupHigh dose ara-C in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia: long-term results of the German AMLCGLeukemia200923122248225819741727

- McClellanJSKohrtHECoutreSTreatment advances have not improved the early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemiaHaematologica201297113313621993679

- MicolJBRaffouxEBoisselNManagement and treatment results in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) not enrolled in clinical trialsEur J Cancer20145061159116824440088

- ParkJHQiaoBPanageasKSEarly death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia remains high despite all-trans retinoic acidBlood201111851248125421653939

- YanadaMMatsushitaTAsouNSevere hemorrhagic complications during remission induction therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia: incidence, risk factors, and influence on outcomeEur J Haematol200778321321917241371

- de la SernaJMontesinosPVellengaECauses and prognostic factors of remission induction failure in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and idarubicinBlood200811173395340218195095

- BreenKAGrimwadeDHuntBJThe pathogenesis and management of the coagulopathy of acute promyelocytic leukaemiaBr J Haematol20121561243622050876

- KwaanHCCullEHThe coagulopathy in acute promyelocytic leukaemia – what have we learned in the past twenty yearsBest Pract Res Clin Haematol2014271111824907013

- MenellJSCesarmanGMJacovinaATMcLaughlinMALevEAHajjarKAAnnexin II and bleeding in acute promyelocytic leukemiaN Engl J Med199934013994100410099141

- IkezoeTTakeuchiAIsakaMRecombinant human soluble thrombomodulin safely and effectively rescues acute promyelocytic leukemia patients from disseminated intravascular coagulationLeuk Res201236111398140222917769

- KawanoNKuriyamaTYoshidaSClinical features and treatment outcomes of six patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation resulting from acute promyelocytic leukemia and treated with recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin at a single institutionIntern Med2013521556223291674

- SaitoAOkamotoYSekiYDIC complicating APL successfully treated with recombinant thrombomodulin alfaJ Pediatr Hematol Oncol2016386e189e19027123666

- MeijersJCOudijkEJMosnierLOReduced activity of TAFI (thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor) in acute promyelocytic leukaemiaBr J Haematol2000108351852310759708

- RegoEMKimHTRuiz-ArguellesGJImproving acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) outcome in developing countries through networking, results of the International Consortium on APLBlood2013121111935194323319575

- TestiAMD’AngioMLocatelliFPessionALo CocoFAcute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): comparison between children and adultsMediterr J Hematol Infect Dis201461e201403224804005

- BallyCFadlallahJLevergerGOutcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) in children and adolescents: an analysis in two consecutive trials of the European APL GroupJ Clin Oncol201230141641164622473162