Abstract

Sipuleucel-T is an autologous cell immunotherapy for castrate-refractory prostate cancer, with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic prostate cancer. In this review we address the background of prostate cancer incidence and other available therapy onto which sipuleucel-T treatment has been added, with discussion of hormone-therapy, chemotherapy, and other investigational immunotherapies. The sipuleucel-T manufacturing process, toxicity and clinical benefit are reviewed, along with an examination of the issue of clinical benefit to survival, independent of apparent changes of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. Sipuleucel-T therapy is appraised from clinician, patient and immunotherapeutic perspectives, with reference to the clinical data from the pivotal trial, the mechanism of action, and the treatment process.

Medical management directions for advanced prostate cancer

The number of people impacted by the burden of prostate cancer is staggering. With tens of millions of men undergoing screening tests, over 2 million US men alive with a history of prostate cancer in 2007, over 200,000 annual new diagnoses and 32,000 US deaths in 2010,Citation1 prostate cancer continues to have a high profile in worldwide oncology and in US healthcare. Fortunately, many cases are biologically indolent, or do not require treatment because they occur in older men for whom there is a lower prostate-cancer-specific risk relative to non-cancer risk of mortality. The subset of patients at high risk for prostate-cancer-specific mortality remains a complex group, for whom the development of better therapies continues in several directions. Among these treatments is immune therapy, studied in many variations within prostate cancer and across oncology. With the 2010 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first cellular therapy and the first immune therapy for this disease, sipuleucel-T (Provenge™, Dendreon, Seattle, WA), prostate cancer may now be one of the main targets for clinical, FDA-approved application of the potent immunotherapy paradigm.

We review here the background of advanced prostate cancer biology and treatment options, other immunotherapy directions, and clinical trials undertaken in the development of sipuleucel-T. We also present the view of patients, the public and oncologists regarding this new approach to treating prostate cancer.

Defining sources of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity is a major characteristic of patients with a diagnosis of prostate cancer. The age at presentation covers decades, and the incidence and comorbidities increase with age.Citation2 The mean number of comorbidities in the NIA/NCI SEER Study sample for those aged 55–64 years is 2.9; for 65–74 years, it is 3.6, and 75+ years is 4.2.Citation3 The higher relative contribution of comorbidities to mortality in older men with prostate cancer should be factored into treatment planning, particularly for lower-risk and localized cases. That risk can be estimated through Gleason scores, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, and localized tumor-stage ratings for locally directed treatments.Citation4 Differences of incidence of prostate cancer in racial groups are well known. African Americans have a 2.5 times higher incidence and over twice the mortality rate of Caucasian men;Citation1,Citation5,Citation6 this is not fully explained by the presence of comorbidities, lack of PSA screening, or access to health care. Genetic factors may be involved,Citation7 but to date there is no direct linkage of genetic studies to therapy choices.

Both tumor- and patient-related factors affect treatment. As in much of oncology, a variety of treatments are available and a decision in favor of any particular option takes into account the estimated likelihood of dying from cancer without early treatment, treatment-related mortality and morbidity, costs, convenience and patient preference. Sipuleucel-T is an expensive treatment, with few immediate side effects. Few data address outcomes based on patient characteristics or preferences, and health-related quality-of-life comparisons between various treatments are sparse.Citation8 Patients make decisions largely on the basis of information received from their physicians.Citation9,Citation10 For many treatment decisions, there is no oncologically absolute standard.

Contemporary options

Besides sipuleucel-T, current options in prostate cancer treatment include active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy (external-beam radiation or interstitial brachytherapy), androgen deprivation, anti-androgens, and cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs. Targeted drugs are in wide development, but remain experimental for this diagnosis. We will discuss the contemporary medical management of prostate cancer in the following sections, with more detail about novel immunotherapy ().

Table 1 A variety of potential therapies, organized by mechanism

Conventional hormone suppression and variations

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs are used widely to achieve decreased testosterone levels, termed medical castration. Successful use of leuprolide in prostate cancer was reported in 1982,Citation13 and US FDA approval for advanced prostate cancer treatment was obtained in 1985. The agonist drugs (such as goserelin acetate, different leuprolide formulations, or triptorelin) bind to GnRH receptors on the pituitary gland, initially causing release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) which in turn increase testosterone production from the Leydig cells in the testes resulting in a “testosterone flare” lasting a week or two. There is eventually downregulation of those GnRH receptors, followed by decreasing FSH and LSH, and consequently suppressed testicular testosterone production, down to castrate levels by about 3–4 weeks. A peripheral anti-androgen, such as bicalutamide, may be co-administered for the first few weeks to avoid symptoms from a tumor flare caused by the transient testosterone increase.

The GnRH analog antagonist drugs were developed much later. These bind (block) at the pituitary GnRH receptor and thus directly decrease FSH and LH and testosterone, without a flare phase. Abarelix was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market, due to a low but detectable incidence of anaphylaxis. Degarelix was approved by US FDA in 2008; it induced testosterone suppression by day 3 in >90% of patients compared to none with leuprolide; at 14 and 28 days median PSA levels were significantly lower in the newer drug group; and both testosterone and PSA suppression were maintained throughout the 1 year study period.Citation11 In a recent preliminary update on the ongoing CS21A studyCitation12 for patients receiving degarelix there was a significantly better PSA progression-free survival (PFS) during year 1 compared to leuprolide treatment. More mature data to directly address a relative clinical benefit (contrasted with an isolated PSA-benefit) for GnRH antagonists are still needed.

Testosterone suppression, whether via surgical castration or medical treatment, has many known potential adverse effects. Some are directly related to androgen deprivation, such as vasoactive symptoms (hot flashes), loss of libido, impotence, fatigue, anemia, changes in body composition (less muscle, more fat), or gynecomastia, as well as more insidious effects such as insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, accelerated loss of bone density (osteopenia, osteoporosis), mood or cognitive changes.Citation14,Citation15 There is a variably negative impact on quality of life. Despite this, testosterone suppression, usually with GnRH agonists, remains the first line hormonal therapy for advanced prostate cancer.Citation16 The subjects in the sipuleucel- T pivotal trial, discussed in detail below, had prostate cancer with progression despite testosterone suppression (castrate-refractory prostate cancer, [CRPC]).

Anti-androgens

Anti-androgens inhibit androgen binding to the androgen receptor (AR) as well as inhibiting androgen-independent activation of the AR protein, a DNA-binding transcription factor. The non-steroidal drugs flutamide, bicalutamide and nilutamide are approved for use in the US while the steroid cyproterone acetate is also approved for use in Europe. When compared to medical or surgical castration, anti-androgen monotherapy showed inferior survival and time to progression and for this reason is not routinely used.Citation17 Sipuleucel-T in combination with anti-androgen monotherapy was not studied in the pivotal trial. Although anti-androgens are generally well tolerated, some adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-androgens include diarrhea and gynecomastia. Diminished visual adaption to darkness is exclusive to nilutamide.

Sequential use of distinct hormonal therapies is often useful. Addition of anti-androgen (combined androgen blockade) to address progression on GnRH analog-mediated testosterone suppression may result in PSA control, for some. For patients who show PSA-progression after combined androgen blockade, anti-androgen withdrawal can induce a sustained PSA response for some.Citation18 The hypothesis behind the withdrawal is that the anti-androgen itself was stimulating the AR, which may have mutated. The in vitro molecular effects of different anti- androgens on AR can vary.Citation19 Novel anti-androgens are discussed below. Trial designs are similar to that of sipuleucel-T.

Some preclinical data suggest that intermittent androgen deprivation, instead of conventional continuous suppression which mimics surgical castration, may delay CRPC development.Citation20 Also, both drug costs and management of comorbidities could decrease with less suppression.Citation21 Most available clinical data on intermittent androgen deprivation are from small Phase II studies,Citation22–Citation24 addressing diverse populations with localized, locally advanced, metastatic disease or biochemical recurrence, using a variety of drug-holiday strategies. From the recently presented results of the SWOG JPR7 trial (1,386 patients)Citation25 the intermittent schedule was non-inferior compared with continuous androgen deprivation for PSA recurrence after definitive treatment, with a median overall survival (OS) of 8.8 vs 9.1 years. The intermittent arm had fewer hot flashes but no difference in other adverse events such as myocardial events or osteoporotic fractures. The EC507 trialCitation26 also found no difference in time to progression for patients with PSA relapse after radical prostatectomy, but significantly fewer side effects were reported. Mature data are awaited from the SWOG 9346 study comparing these approaches in metastatic prostate cancer.

Currently, intermittent suppression is considered in selected patients. The testing of sipuleucel-T was focused on patients already refractory to hormone therapy, whether the prior testosterone suppression had been intermittent or continuous. While the scale of these intermittent hormone therapy trials, in terms of number of patients enrolled, is comparable to the sipuleucel-T pivotal trial, the time-scale for the duration of active use of the treatment being studied is much longer. Similarly, the survival times and follow-up duration are much longer than all the studies on CRPC patients, where a median OS endpoint is observed in about the 12–24 month range.

Other drugs affecting the hormone axis

Ketoconazole is an antifungal agent which is a nonspecific weak inhibitor of cytochrome CYP17, an enzyme of androgen biosynthesis. Administered at doses higher than used for antifungal therapy, with hydrocortisone (because of the side effect of cortisol suppression), ketoconazole can effect further decrease of testosterone and then a PSA response in as many as 30%–60% of selected patients with PSA progression, with a variable duration of months to years. Some limitations include potential side effects such as nausea, anorexia, hepatic dysfunction, nail dystrophy or rashes.Citation27,Citation28 Second-generation androgen biosynthesis inhibitors such as abiraterone, discussed below, may overcome some of these limitations.

Corticosteroids such as prednisone and dexamethasone are also active in prostate cancer. These have been used as partner drugs for docetaxel, mitoxantone, and abiraterone, or as single agents, with a potential favorable impact on bone pain, and on drug tolerability. One trial reported a PSA response rate of over 60%,Citation29 but a much lower response rate and duration of corticosteroid monotherapy is the general experience. In contrast, most immunotherapy approaches, including sipuleucel-T, are tested with a specific, systematic exclusion to address the immunosuppressive potential of corticosteroids, particularly on lymphocyte activation, proliferation and survival. However this makes it harder to understand how or when combinations with corticosteroids, should be used with sipuleucel-T.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs

Docetaxel (Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) was the first systemic chemotherapy specifically showing an improved median survival in two Phase III studies compared to mitoxantrone.Citation30–Citation32 The reference treatment plan, mitoxantrone, in combination with corticosteroid, was previously shown to have a quality of life benefit.Citation33,Citation34 The similarities and differences of the groups being treated, compared with the patients in the sipuleucel-T trial, can be debated. While the sipuleucel-T trial was limited to minimally symptomatic patients, both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients were the subject of the positive trials that helped to establish docetaxel, once every three weeks, with concurrent daily oral prednisone, as the main initial cytotoxic chemotherapy in use for progressive CRPC. As discussed below, many of the patients in the sipuleucel-T trials did subsequently receive docetaxel chemotherapy. The first second-line-chemotherapy with a positive Phase III trial, specifically tested in post-docetaxel CRPC patients, is cabazitaxel (Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France).Citation35 Patients who had generally initially responded but subsequently progressed on docetaxel were randomized against mitoxantrone and a significant overall survival advantage was observed. The safety and toxicity features of the new taxane were appreciable, with grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in 82% patients, febrile neutropenia in 7.5% patients, diarrhea in 6% of patients and death related to adverse events in 5% of patients.

Increases in median survival time observed in these taxane studies can be compared to those observed in the pivotal trial of sipuleucel-T. In the SWOG 9916 trial, survival was 17.5 months in the docetaxel arm vs 15.3 for those randomized to mitoxantrone; in the TAX327 trial, 19.3 months vs 16.3 (comparing once-every-3-weeks docetaxel to mitoxantrone); and in the TROPIC (cabazitaxel vs mitoxantrone) trial, 15.1 vs 12.7 months.Citation30–Citation32,Citation35 Some recent cytotoxic chemotherapy-based Phase III trials, conducted on a similar multinational scale with about 1000 patients, that did not demonstrate a survival advantage, include docetaxel without or with bevacizumabCitation36 and satraplatin plus prednisone vs prednisone alone.Citation37

Newer hormone-pathway drugs

Every new drug development is awaited by the prostate cancer community, and represents a challenge to the clinician for use of the new drug instead of those already on the market. Sipuleucel-T is now part of that dynamic, with respect to newer hormone-pathway drugs. MDV3100 (Medivation, Inc, San Francisco, CA) is a novel small-molecule selective AR antagonist that has three complementary actions on cancer cells: blockage of testosterone binding to AR; impediment of AR nuclear translocation (movement from cytoplasm to nucleus of activated, dimerized AR); and inhibition of DNA binding by AR.Citation38 The latter two mechanisms are not found in the marketed nonsteroidal anti-androgens and cyproterone acetate. MDV3100 also lacks AR agonist activity. Tested in vitro, MDV3100 slowed growth and killed castration- resistant and bicalutamide-resistant prostate cancer cells.Citation38 Phase II data were encouraging, with >50% PSA responses in 56% of the CRPC patients, median time to radiologic progression of 10.8 months, decrease in circulating tumor cell (CTC) counts, and favorable side effects (dominated by fatigue) which responded to dose reduction. The AFFIRM trial (NCT 00974311) in CRPC patients is a pivotal trial vs placebo, after docetaxel treatment, and has completed accrual. The PREVAIL trial (NCT 01212991) is ongoing in chemotherapy naïve CRPC subjects.

Abiraterone (Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc, Horsham, PA) is an inhibitor of the cytochrome enzyme CYP17, as is ketoconazole, but is more potent, and also inhibits the cytochrome 17–20 lyase.Citation39 Besides decrease of systemic testosterone, intratumoral testosterone synthesis may be suppressed as well.Citation40 Compared to ketoconazole hormonal side-effects, treatment with abiraterone has less cortisol suppression, but more aldosterone formation. Early phase studies were promising, with 67% of patients demonstrating >50% declines in PSA,Citation41 and in the post-docetaxel setting, 43%–51% achieving that PSA benchmark.Citation42,Citation43 Additionally, there were partial radiographic responses in 37.5%.Citation41 Results from the pivotal Phase III demonstrated a median OS of 15.8 months with abiraterone vs 11.2 months with placebo.Citation44 It now has US FDA approval for use in patients with metastatic CRPC who have received prior docetaxel treatment. Results of another Phase III study (COU-AA-302, NCT00887198) of abiraterone vs placebo for chemotherapy naïve metastatic CRPC are keenly awaited.

Other novel hormonal agents in development include TOK-001 (Tokai Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA), which is also a potent blocker of the AR, and TAK-700 (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Osaka, Japan), another inhibitor of androgen synthesis.Citation44

Novel cytotoxic drugs

Sipuleucel-T can be contrasted with the regimens for treatment with cytotoxic drugs, looking at cumulative infusions, burden of side effects, duration of active treatment and drug expense. The process of developing algorithms for strategic sequencing or combination of new agents, including sipuleucel-T and other novel immunotherapies remains incomplete.

Balancing the experiences of positive Phase III trials using cytotoxic drugs (mitoxantrone, docetaxel, cabazitaxel)Citation30–Citation34 against negative ones,Citation36,Citation37(docetaxel with bevacizumab, satraplatin) there is still continued interest in the development of chemotherapeutic treatments while recognizing that some patients are averse to intravenous treatment or risk-averse to fatigue or other typical side effects. The need for ongoing randomized trials is underscored, even in the face of encouraging Phase II, nonrandomized, PSA-based results.

One example of a cytotoxic drug category with new application in anti-prostate-cancer therapy is the epothilones, such as patupilone and ixabepilone. These have a mechanism of action similar to that of taxanes but differ in their binding and interaction with β-tubulin.Citation46 A randomized study of ixabepilone against mitoxantrone (with cross over from mitoxantrone to the new drug allowed) was reported, with the median survival, PSA responses and partial responses similar in both groups.Citation47

Development of sipuleucel-T

Concepts of antigen presentation and immune activation

The central goal of immunotherapy is activation of an immune response directed against tumor cells while overcoming tumor-induced tolerance.Citation48 Prostate cancer has a few characteristics that make immunotherapy attractive. These are:

The presence of a variety of tumor-associated antigens such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), and others that are cancer- or organ-specific.

It is, at least initially, a slow-growing disease thus offering enough time for the stimulated immune system to generate an antitumor response while overcoming immunosuppressive factors.Citation48,Citation49

Spontaneous autoantibodies, as shown by phage protein microarrays, indicate that a nascent immune response may be already present, with the potential to be amplified.Citation50

The prostate is a dispensable organ, therefore the use of passive immunotherapy is relatively safe, because any autoimmunity generated would have little, if any, consequence to the patient.

To be effective, cancer vaccines enhance activation of tumor-specific T-cells with concurrent reduction of immunosuppression. Citation51 T-cells attack tumor cells and induce regression. Natural killer (NK) cells can also mediate anticancer immunity.Citation52 Data suggest a positive correlation between the presence of tumor infiltrating CD8+ T-cells and good prognosis in various types of cancer.Citation51 There are several intratumoral mechanisms that impair immune attack including class I HLA downregulation (corresponding to decreasing susceptibility to CD8 CTL lysis),Citation53–Citation55 PD-1 ligand expression,Citation56,Citation57 and Fas-ligand expression (each inducing apoptosis or de-activation of infiltrating lymphocytes).Citation58 Tumor secretion of inhibitory cytokines, indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenaseCitation59 and nitric oxide synthetaseCitation60,Citation61 can also protect tumors from attack. Local expression of cytokines including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and tumor growth factor beta (TGF-β), which induce a tolerogenic phenotype in antigen presenting cells (APC), may be examples of general tumor anti-immune pathways.

The goal of anticancer vaccines is thus modification of the interaction between tumor cells and the immune system so the latter will escape suppression. In the context of an established cancer, an existing, pathologic self-tolerance must be broken. In order to produce an effective immune response, selection of the appropriate antigen needs to be combined with activation of APCs so that the host’s immune system can then mediate the antitumor effect.

APCs are responsible for uptake, processing, and presentation of antigens to immune system T cells in the context of HLA class I and class II molecules.Citation62 Dendritic cells (DC) are considered to be the most potent APCs with powerful T cell priming properties. They also have the capacity to activate naïve and memory B cells as well as NK cells and T cells.Citation63 Since antigen-loaded DC can elicit a beneficial cellular immune response, vaccines based on DC have been used for the development of cell-based therapies. Sipuleucel-T is based on directly loading the autologous APC and DC with the prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) antigen.

Methods of clinical immune activation

Dendritic cells have proven to be a good route for the vaccination process.Citation63 Data from murine models supported early phase trials using DC loaded with an engineered antigen-cytokine fusion protein (PA2024) consisting of PAP and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), for which there are receptors on APC.Citation64 This combination induces strong cellular immune responses in vivo to tissues and tumors that express PAP. The role of GM-CSF is a key factor for activating APC since dendritic cells pulsed without GM-CSF (PAP alone) elicited significantly weaker immune responses.Citation62 Data also demonstrated that isolated DC could be exposed to tissue- or disease-associated antigens in vitro and re-infused to stimulate immunity to those antigens,Citation65,Citation66 showing measurable antitumor cellular immune responses.

Sipuleucel-T takes advantage of DC properties to make PAP a more attractive antigen to the immune system. The manufacture of sipuleucel-T includes the collection of dendritic cells from prostate cancer patients and activation ex vivo with recombinant fusion protein PA2024. This PA2024 consists of PAP linked to GM-CSF. The process itself is proprietary and is performed in a central facility for all the procedures. First the patient has an apheresis, and the bag with the collected leukocytes (unprocessed white blood cells) is shipped to the Dendreon central facility. The product is prepared from the collected cells by co-culturing APC for 36–44 hours in media containing PA2024. When the product (white blood cells, now sipuleucel-T) is certified, it is transported back to the local center as infusible autologous cells. As specified by the manufacturer Dendreon, the infusible product contains APC (at least 50 million CD54+ cells) and also 60%–70% lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells. Both the DC and the lymphocytes may contribute to, or constitute, the clinical activity. Patients will have three apheresis and infusions, generally at 2-week intervals. The use of a series of three may be of significance (vs serial application of cells from a single apheresis), because it allows for a boost-and-prime paradigm, with direct analogy to classical vaccination.Citation67

Off-the-shelf vs custom manufacturing

Most new drugs, particularly immunotherapeutics, face challenges to their acceptance. Reasons include high production costs, limited resources for distribution, and resistance from the medical community because of modifications needed to deliver the drug, or a low level of confidence in the novel mechanisms of action. The patients’ perspective on the drug or drug class must also be considered – for many “immunotherapy” has a desirable cachet that “chemotherapy” cannot ever achieve. Convenience and simple administration of the treatment are essential. Despite the challenges, cancer vaccines provide an attractive option for patients given their outpatient administration and lack of common side effects associated with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics.

Autologous tumor vaccines are personalized products that contain a specific tumor-associated antigen. The tailored production of autologous vaccines, like sipuleucel-T, sacrifices the convenience and lower production costs associated with off-the shelf agents readily available for use. These factors may make custom production less attractive to the cost-conscious health-care environment. In addition, both autologous and allogeneic vaccines have shown remarkable limitations in creating strong and durable immune and tumor responses.

Selection of a test-population

The selection of a sub-population of prostate cancer patients for Phase III trial testing has implications both for the chance of observing a response, and for the definition of the population for subsequent off-study clinical application. When using immunotherapy, one has to consider the underlying mechanisms driving the cancer and also the aging process of the patient’s immune system; these define different contrasting immune-contexts.Citation68 Most prostate cancer patients are older men who have achieved an immune “maturity” which favors an inability to produce naïve T cells. This is, biologically, a contrast from in vivo testing in young mice. The effects prior treatment may have had on patients’ immune systems are also relevant, as well as the long duration of exposure of the immune system to the tumor. There may be opportunity for better or worse timing of the same treatment. In the sipuleucel- T pivotal trial, some patients were previously treated with cytotoxic agents, potentially representing a population that is less able to benefit from immunotherapy when compared to treatment-naïve patients or even hormone-sensitive patients in earlier stages of their disease.

The capacity of the immune system to tackle tumor cells may vary along with the disease course and is compromised by age.Citation69,Citation70 Assuming relevant increases of tumor tolerance during disease progression, it might be reasonable to introduce sipuleucel-T earlier in the course of the disease. There may be a population that might be more competent and fit to mount an immune response and take advantage of immune modulation, as compared to the population used in the pivotal trial.

Ultimately, the design of a pivotal trial represents a balance between the most urgent clinical need, the broadest market, and the best immunologic context. For the case of sipuleucel-T, several subset populations could be explored in future testing. For example instead of hormone-insensitive, minimally symptomatic patients, a study could focus on symptomatic, hormone sensitive prostate cancer patients (earlier in the disease course, but anticipating shorter hormone-response duration) where a larger clinical impact may be observed.

The process of defining clinical trial end points for a novel immunotherapy treatment can be difficult, since immediate regression of the tumor has not occurred. A significant latency, dependent on the generation of the immune response must be allowed, in contrast to the direct anti-tumor activity of classic cytotoxic chemotherapies. This makes PSA-response or time to progression a difficult intermediate marker to correlate with overall survival. Maximal T-cell reactivity could take 8 to 10 weeks to achieve.Citation71 Evaluating for TTP before or during this window may miss the potential immune antitumor effect. This factor may have been illustrated when some patients developed progressive disease before the treatment achieved its biologic effects.Citation71 Stable disease state, or a better response to chemotherapy after exposure to sipuleucel-T might be reasonable end points for future clinical trials. Evaluation and measurements of the immune response (that is, titers of antigen-specific T cells) might add to this data guiding the timing and administration of the sipuleucel-T, particularly in chemotherapy-naïve patients, or other contexts where the pace of potential clinical progression is slower. However, these surrogate endpoints cannot replace the survival comparison.

Monitoring the effect on PSA should also be considered as a reliable marker of tumor response in clinical trials, while recognizing its limitations, particularly in cases of high Gleason scores (greater than 7). PSA level gives an early sign of drug utility and has particular relevance as a pharmaceutical drug development “signal” in prostate cancer therapeutics. Citation72 The potential for a disconnect between PSA-response and survival response remains a concern, however.

Biological diversity of prostate cancer in minority populations and younger patients is an area of ongoing study. As sipuleucel-T becomes more easily available, potential immunologic response features in under-represented populations in the pivotal trials, such as African-Americans, and younger patients, could compared to the current, predominantly Caucasian and older population data. This will be of particular interest since prostate cancer is known to have a higher incidence in African-Americans. This can be related to the heterogeneity of cancer and also to cultural disparities.

Safety and efficacy and pivotal studies

Trial structure and inclusion criteria

The 2010 US FDA approval of sipuleucel-T was based on the pivotal trial Immunotherapy for Prostate Adenocarcinoma Treatment (IMPACT).Citation73 This Phase III clinical trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study that included asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic men with metastatic CRPC. As part of the inclusion criteria, patients with progressive disease (on imaging studies or based on PSA levels), with a PSA level of ≥5 ng/mL or more, and serum testosterone level of less than ≤50 ng/dL (castrate level) were eligible. Pretreated patients (18.2% had fewer than two chemotherapy treatments) and those with bone disease were included, but visceral metastasis was exclusionary.

Based on initial data from the earlier trial,Citation71 patients with a Gleason score higher than 7 were initially excluded. After further analysis of that data demonstrated that the positive treatment effect of sipuleucel-T was independent of Gleason score, the IMPACT protocol was amended and all histologic grades were included.

Five hundred and twelve patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either sipuleucel-T (341 patients) or placebo (171 patients) administered intravenously at an interval of at least 2 weeks, for a total of three infusions.Citation73 Sipuleucel-T was prepared at a central facility as detailed on the package insertCitation74 by culturing the leukocytes obtained from apheresis, processed to isolate APC and lymphocytes. These were cultured for 36–44 hours, at 37°C with media containing PA2024. For the study, each dose of sipuleucel-T or placebo contained a minimum of 40 million large cells expressing the co-stimulatory molecule CD54.Citation73 This is slightly lower than is specified on the marketed product package insert. Study design allowed the crossover of patients with evidence of progression of disease to be part of an open-label salvage protocol and receive APC8015F, a product manufactured according to the same specifications as sipuleucel-T but prepared from cells cryopreserved at the time the placebo was prepared.Citation73 The APC8015F product, therefore, would be administered at a point later in the disease course, and without the tandem collection of new apheresis product at intervals after the prior infusions.

Although the primary endpoint was OS, the objective disease time to progression (TTP) was monitored as well, using serial computed tomography (CT) at weeks 6, 14, 26, and 34 and every 12 weeks thereafter and serial bone scans at weeks 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, and 34 and every 12 weeks thereafter. PSA levels were monitored at the same intervals as the CT scans.

Primary outcome

Overall survival, defined as the time from randomization until death from any cause, was the primary end point; time to objective disease progression was the secondary end point. The OS was analyzed with PSA levels and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) adjustments, given their strong correlation with prognosis as shown in prior trials.Citation71,Citation75,Citation76 A 4.1 month difference in median survival was seen in the experimental arm (25.8 for sipuleucel-T group vs 21.7 months in the placebo group; hazard rate 0.78, P = 0.03). The median time to objective disease progression was 3.7 months in the sipuleucel-T group and 3.6 months in the placebo group, which was not a statistically significant difference.

Immunologic outcomes

Documentation of the immune responses during exposure to sipuleucel-T provides some insight about the treatment population. In some ways, this is a technical and not clinical perspective. However, the immune response patterns define a direct connection to the proposed mechanism of action, and may be a direct connection to a next generation of immunomodulator, adjunctive drugs.

With the objective of analyzing humoral immune response, antibodies against the immunizing antigen PA2024 and to PAP were evaluated, with a threshold titer of >1:400 used to define a response. Anti-PA2024 was observed in 66.2% of the patients in the sipuleucel-T arm compared to 2.9% in the placebo group. Titers greater than 400 for anti-PAP response were also greater in the treatment arm (28.5% vs 1.4% in the placebo group). Both differences were statistically significant.

T-cell proliferation responses against PA2024 were observed in 73.0% of the sipuleucel-T arm vs 12.1% in the placebo group. Similar results were obtained for responses to PAP with 27.3% in the experimental arm vs 8.0% in untreated population. These differences were also statistically significant. When analyzed against the survival data, the antibody against PA2024 was significant (P < 0.001), and there was a trend in the response to the antibody to PAP (P = 0.08), but the week-6 T-cell proliferation did not define a difference. It is possible that a later, or different, or combination immune assay would define the group with the best sipuleucel-T induced clinical response. Higher CD54+ cell count, higher total nucleated cell count, and CD54 upregulation were all correlated with a better survival.Citation75 This suggests that heterogeneity of the immunophenotype of the prostate cancer population, and heterogeneity of the incremental response could be defined and tested. The result of that testing could define a group for which there is a disproportionately better treatment-response.

Progression free survival – description and interpretation

The validity of clinical trials relies on a prospectively-defined, clinically relevant end point. As previously mentioned, OS was the primary end point of this pivotal trial. The crossover study design had potential contamination of the OS endpoint. Thus, even with the benefit of 4.1 months, no PFS impact was seen. The same pattern was previously seen by Small and colleagues in another randomized sipuleucel-T experiment, where TTP did not improve, but there was 4.5 months’ median OS advantage.Citation71 The data from two Phase III trials were integrated,Citation77 also with only a trend towards a delay of TTP.

The assumption used in developing the trial inclusion characteristics: that for asymptomatic patients, a slower progression of their disease could allow more time for the immunotherapy to work and slow the TTP, was not borne out. The TTP seems comparable to that in symptomatic patients.Citation71 Taken together, the conclusion is somewhat counterintuitive: the disease progression end point does not appear to be a reliable predictor of OS, for this population.Citation73

Safety

The limited toxicity profile associated with immunotherapy is an attractive feature of many such treatments, at least for active immunizations. In these sipuleucel-T Phase III data, only three patients (0.9%) were unable to receive the three planned treatments due to infusion-related adverse events. Immune-related adverse events associated with sipuleucel- T more than with placebo were chills, fever, headache, influenza- like illness, myalgia, hypertension, hyperhidrosis, and groin pain. Most of these (except groin pain) resolved within 24–48 hours. These adverse effects were reported in 65.2% of patients and were mostly grade 1 or 2. Grade 3 adverse effects in the treatment arm were chills, fatigue, back pain, hypertension, hyperkalemia and muscle weakness. Only one grade 4 event due to catheter-associated infection was reported in the treatment arm. Grade 3 and 4 events were reported in 6.8% (23 patients) vs 1.8% (3 patients) in the placebo group.

Stroke was the most significant adverse effect reported with the use of sipuleucel-T. In the pivotal trial, 2.4% of patients (8 of the 338) in the sipuleucel-T arm developed cerebrovascular events. An FDA-mandated post-marketing evaluation of the frequency of that type of event is ongoing. The majority were nonfatal with a median interval from last infusion to event of 210 or 196 days (sipuleucel-T group or placebo).Citation73

Selected other investigational immunotherapies

Both normal parenchymal prostate tissue and prostate cancer tissue bear antigens for which an anticancer immune attack with a clinically significant impact can be theoretically generated, without affecting other critical tissues. Sipuleucel-T, focused on PAP, is one of several different development efforts. However, the problem is not the issue of stimulation of a response to a single protein, but rather of changing the patient’s general immune response in a way that can defeat the tumor-induced state of tolerance. Some clinical developments on the scale of the sipuleucel-T pivotal trial have been completed, or are anticipated in the coming years.

Considering some investigational immunotherapy strategies for which there is an application specifically in prostate cancer, and which are based on a restricted, specified antigen, there are several in current development. Two use a viral vector to deliver PSA to the immune system, based in one case on modified vaccinia and fowlpox viruses (PROSTVAC- VF) and in the other one an adenoviral vector.

PSA-viruses

A common concern with virally-based treatments is the safety of the parent virus; the vector is one for which the human immune system is competent to generate a protective response, eradicating infection. The genomes of two modified viral vectors, vaccinia and fowlpox, have been modified in Prostvac to contain the code for PSA, so that as virally infected cells are exposed to immune processing and attack, PSA will be treated as a viral protein for rejection, rather than a self-antigen leading to usual, but pathologic, tolerance. A further modification is the addition of a 3-part costimulatory transgene (designated as TRICOM). These code for the DC cell surface receptors B7-1[CD80], ICAM-1, and LFA-3, which have stimulatory effects on their T-lymphocyte ligands (B7.1:CD28, ICAM-1:LFA-1, and LFA-3:LFA-2 [CD2]).Citation78 In this way, the presentation of the PSA-associated antigenic peptides in HLA context will be stimulatory. The use of two different viruses was derived from a prime-boost strategy, with the modified vaccinia virus portion (rV-PSA-TRICOM) used initially, and generating a strong immune response, including one directed to the viral antigens but not emphasizing the PSA. The later administration of the fowlpox virus (rF-PSA-TRICOM)Citation79 serves as a boost, with a vector which dominates the immune response less. The vaccination schedule uses one dose of the rV-PSA-TRICOM and then subsequent monthly doses of rF-PSA-TRICOM.

Reported clinical trial results include some patients with PSA declinesCitation79 and across Phase II trials, a decline of PSA-growth rate-constants.Citation80 A current Phase II study randomizes CRPC subjects to treatment with docetaxel and prednisone with or without vaccination.

The development of clinical trials using the same vector framework (TRICOM, vaccinia, fowlpox), with other antigens is ongoing. Among these is the muc-1 protein,Citation81 which is a glycoprotein that has markedly different glycosylation patterns and antigenic features in cancer cells (as opposed to its physiologic expression), as a consequence of impaired glycosylation pathways. In addition to PSA, this antigen is of at least theoretical interest in prostate cancer immunotherapy, along with possible application in other adenocarcinomas that express abnormally glycosylated muc-1 protein. Other muc-1 directed prostate-cancer-specific immunotherapies are also in development, for example the nonviral, liposomal product L-BLP25.Citation82

A modified adenovirus (Ad/PSA) was tested in a Phase I trial by Lubaroff et al in Iowa. The vector itself may have a capacity for generating a stronger anti-PSA response than the pox virus vectors.Citation83 The product showed good safety experience, and a third of patients (34%) had generation of PSA antibodies, two-thirds (68%) with increased detectable T lymphocytes with anti-PSA specificity, and half (48%) with apparent declines of PSA doubling time.Citation83 Further clinical testing is ongoing, comparing vaccine treatment without or with hormone suppression (NCT00583752) or in CRPC (NCT00583024).

PSMA

Prostate specific membrane antigen, PSMA, is not limited to prostate tissue. Despite the word “specific” in its name, PSMA is distributed both in prostate cancerCitation84 and in the endothelium of non-prostate cancers.Citation85 Both histologic sites of PSMA are of interest for the development of anti-PSMA directed cancer therapy. The development of a spectrum of approaches encompasses both passive targeting with toxins, viruses or radioactive drugs, and active immunization with proteins and peptides.Citation53,Citation86 The DCvax product is one that was developed in early phase clinical trials, a decade ago.Citation87 The process of preparation has some parallels to sipuleucel-T. Leukapheresis was used to obtain a DC product, for each patient, and these DC were pulsed with peptides derived from PSMA, and then re-infused again at intervals. The data from some of these trials describe some PSA responses,Citation87 but no Phase III trial was conducted. Whether the successful marketing of sipuleucel-T as an autologous DC vaccine will be a catalyst for the development process for other autologous dendritic cell vaccines using PSMA or other antigens remains to be seen.Citation53 The BPX-101 product was recently reported in a clinical trial with some clinical responses and PSA regression. It consists of autologous PSMA-loaded dendritic cells that are injected intradermally, followed by a dendritic cell activating drug, AP1903. (Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Houston, TX).Citation88

Our group has developed a clinical trial using peptides that represent epitopes of the protein PSMA and the protein TARP (TCR [T cell receptor] gamma alternate reading frame protein), that can associate with HLA-class I and class II-proteins and is administered in conjunction with the toll-like receptor-3 (TLR-3) agonist poly IC-LC, with the objective of demonstrating immune response toward those epitopes. (NCT00694551). No results have been presented.

Tumor cell vaccines

There are many immunologic details that define distinctions among vaccines using tumor cells vs those using isolated peptides or proteins. Whole cell vaccines have a broad array of antigens, which could induce a more potent reaction, but the particular cancer-related antigens are diluted by other tumor proteins. Another concern is that some component of the tumor cell proteins, such as matrix metalloproteinases, could actually mediate immune tolerance.Citation89

A tumor cell anticancer vaccine which had two Phase III trials that were contemporary with the sipuleucel-T trialCitation73,Citation74,Citation77 was GVAX (CellGenesys, South San Francisco, CA). This off-the-shelf product consists of two human allogenic prostate cancer cell lines (LnCAP and PC-3). The cell lines were modified further to produce GM-CSF, which should cause regional dendritic cells to be activated at injection sites, with a variety of relevant antigens obtained from the tumor cell material, including PAP (as emphasized in sipuleucel-T), PSMA, PSA, and others.Citation90,Citation91 GM-CSF gene transduced cell line vaccines allow cross priming by avoiding the requirement for human leukocyte antigens (HLA)/major histocompatibility complex matching between the cell lines and the patient. In contrast with sipuleucel-T, GVAX is consider to prime the T-cell to have an antitumor response against a broader range of tumor associated antigens, but this is limited by the capacity of the host and the host’s antigen presenting cells to mount a competent immune response.

One of the Phase II GVAX trials was designed to include hormone-naïve HRPC men with recurrent disease (after definitive surgery) and elevated PSA in the absence of radiologic metastatsis.Citation92 There was a clinical immunological response by PSA in the responder group suggesting that immune competence (defined as hormone/chemotherapy-naïve patients) plays an important role in the timing of immunotherapy exposure. Evaluating the immune clinical responses and survival benefit in immunologically different populations (the rest of the GVAX trials included pretreated patients) does not seem to generate comparable results. Despite early promising results, including an instance of sharp PSA regression, later clinical trials were unable to demonstrate benefit.

The VITAL-1 trial of GVAX vs docetaxel + prednisone (NCT00089856), limited to subjects with metastasis and without significant cancer-related pain, finished accrual (N = 626) but was ended with less than a 30% chance of meeting the overall survival primary endpoint. The accrual from the VITAL-2 trial of GVAX + docetaxel vs prednisone + docetaxel (NCT00133224) was stopped early due an excess of mortality on the investigational arm (67 vs 47; N = 408 accrued).Citation93 It is not known whether a different disease subpopulation, or a different adjunctive treatment would result in a more useful anticancer immunotherapy.

Although the immunologic basis for the absence of benefit could not be determined directly from the available clinical data, several theoretical details which contrast with sipuleucel-T can be considered: were the patients, overall, too advanced to have competent acquisition of new immunity, or conversely were the tumors too established, or too rapidly growing to respond to immune attack? Did the inclusion of glucocorticoid impede a useful vaccine response? Did the potential for tolerance emanating from exposure to allogeneic, cancer-irrelevant antigens crowd out the capacity for quantitative immune response to the relevant tumor antigens? Is it more difficult, in human disease, to simultaneously break tolerance for many antigens than for one?

Immune modulation not connected to specific antigens

A variety of general immune modulators may be relevant to the challenge of generating clinically useful anticancer immune responses. One that is in advanced clinical development is the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilumimab (Yervey™, formerly MDX 010, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York). The CTLA-4 cell surface molecule is on T lymphocytes and mediates lymphocyte downregulation following antigen-specific activation and proliferation. Through attenuation of that response, anticancer activity may be increased. Among several prostate cancer directed studies addressing use in neoadjuvant, combination with GM-CSF, and combination with docetaxel, a Phase III randomized study (ipilumimab vs placebo) in post-docetaxel, CRPC has been initiated (NCT01057810). The experience of a positive Phase III trial in melanoma therapy was reported in 2010 and FDA approved March 2011,Citation95 leading to considerable optimism for further development in other cancers as well.Citation96

Overall, since many of these other immunotherapies rely on mechanisms that are potentially complementary to sipuleucel-T, there is hope that future combinations could amplify the anticancer impact.

Patient perspectives: adherence and acceptance

Defining goals of therapy

For any anticancer therapy, both physician and patient must understand the potential benefits and limitations. In many settings, such as a radical prostatectomy, these can be defined in concrete terms: chance of cure, risk of urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, or other surgical complication. In that clinical setting, the feedback on these questions is almost immediate, in the days and weeks after the operation.

Among those patients with elevated PSA after definitive-intent local therapy (mostly radiation and surgery), many have, at least initially, no other radiographically or clinically identifiable disease. For those who have no specific anatomically identifiable metastasis, it is the PSA level that is the most accessible measure of disease response. The usual androgen suppression treatment approach gives an almost immediate feedback on the effect of treatment, visible as a fall of PSA, and potentially also a measurement of testosterone suppression.

While immediate feedback is gratifying, for both physician and patient, there remains a reality-check that is not always appreciated: PSA is not a toxic substance in itself. While most therapies’ treatment effect is visible as a PSA response, that may not translate directly into an impact on symptoms nor overall survival. Indeed, initial definitive local treatment of indolent prostate cancer is emerging as a paradigm of a treatment with potential for more harm than good among elderly patients with comorbidities that represent a greater threat to overall survival. Algorithms to optimize an individualized assessment are evolving, and some are available, for example the Japan Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (J-CAPRA) instrument.Citation97

PSA vs OS

Looking at CRPC, there is now a potentially weaker direct connection between PSA changes and survival impact, both for individual and group experience. Most trials, especially docetaxel based studies, have suggested that treatment decisions can be based on PSA patterns, particularly during drug development.Citation98 PSA decrement and clinical benefit are closely connected in studies with docetaxelCitation30,Citation31 and cabazitaxelCitation35 and the recently presented abiraterone data.Citation45 However, two recent CRPC Phase III trials demonstrated a different pattern, with apparent benefit in controlling PSA and tumor size, but then with no overall survival benefit. A trial of satraplatin showed that for the time to pain progression, the hazard ratio (HR) improved significantly (0.64; 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.79; P < 0.001), the PSA responses were higher more frequently (25.4 vs 12.4%. P < 0.001), but no significant OS difference was observed (HR = 0.98, P < NS).Citation37 The similarly sized (1001 patient) trial of docetaxel without or with bevacizumab showed more PSA-response and tumor-responses in the combination arm (69.5 vs 57.9, P = 0.0002 [PSA] and 53.2 vs 42.1, P = 0.0113 [objective response]), but still no significant OS impact (HR = 0.91, P = R 0.181, NS).Citation36 With these experiences in mind, the distinction between short-term PSA impact and eventual OS can be better appreciated.

A disconnect has been observed, at least in one direction, in large, randomized experiences for a PSA-response, and progression-free survival/overall response (PFS vs OS). The question relevant to sipuleucel-T is: if there can be a PSA impact, but no survival impact for some drugs, can there be a survival impact, but no evident immediate disease impact for an immunotherapy? The most straightforward explanation is that the latency of the anticancer effect is typically longer than the benchmark time point for PSA or progression assessment. For example, if maximum T-cell reactivity can take up to 10 weeks to achieve,Citation70 early progression would not be a surprise finding.

For the aggregate sipuleucel-T trial data, this is a straightforward conclusion: the same result was observed across three randomized studies, and the review of the data, and the maturation of the data mandated by the US FDA support the conclusion that for the cohort of patients randomized to sipuleucel-T in the trials, a survival benefit of about 4.1 months, at the median, was observed.

“PSA-believers”

For a prostate cancer patient who may have seen PSA response at prostatectomy, PSA response at initiation of testosterone suppression, PSA response with addition of bicalutamide, and PSA response with docetaxel + prednisone treatment, but is now presenting meeting nominal asymptomatic CRPC criteria as were used in the pivotal trials of sipuleucel-T, how does one develop an expectation for the outcome of such therapy? The appeal of anticancer immunotherapy is enormous. Although sipuleucel-T is an autologous cellular product, the term “vaccine” projects a ready image of a rapid, holistic and protective response, such as a seasonal influenza vaccine. In contrast to a group analysis, as is usual for an individual’s isolated experience, there is no perspective on what difference in OS occurs.

We anticipate this will remain a question that is difficult to answer. Surely, some patients have more benefit, and some less. The extent to which an individual fits with the clinical features of the group that was studied Citation71 can increase the confidence of a treatment recommendation, but still falls short of a prediction that can be individualized. Indeed, the specific experience for the well-selected patient suggests an unsettling choice: if the PSA were rising, it would continue to rise if sipuleucel-T is used, or alternatively, it would continue to rise if sipuleucel-T is not used.

For the clinician faced with a making a medical recommendation, the absence of early feedback on treatment response also has an unsettling parallel: for a patient whose clinical features do not match well those of the US FDA label or the pivotal trial, the same PSA pattern would be observed.

The pricing of Provenge™, at US$ 93,000 (wholesale) for the series of three infusions, naturally also creates a discussion point. For whom should such expenditure be justified? Most US patients will be reliant on third-party payer support for treatment, which can be anticipated to be relatively conservative with respect to alignment with the pivotal trial data.

Similar debates can be anticipated as any new drug is introduced. The high price of this, or other new cancer drugs (for example abiraterone is about US$ 50,000 a year and ipilumimab about US$ 120,000 per course of four treatments) is one that puts the spotlight sharply on a balance of cost for a possible individual benefit vs the identifiable public benefit. How closely must an individual duplicate the inclusion criteria of the pivotal trial? Where, when and for whom will the cost-per-survival increment meet a tipping point to deny coverage? Will that border be drawn on a “scientific” basis, or economically controlled?

Each national health policy and each insurer will evaluate treatments from a different perspective. Unfortunately, the established system precludes easy availability of sipuleucel-T to eligible patients, mostly due to the cost. There is an ongoing review of the pivotal study design, end points and outcomes with the purpose of justifying reimbursement by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.Citation98

Inevitably, differences in patterns of use in different insurance and economic settings, and national health policies and cultures can be anticipated. Factors such as Medicare coverage decision, entry of other (more convenient) but expensive drugs (namely abiraterone in the last month), will influence both patients’ preferences and physician prescribing patterns. Construction of a sipuleucel-T production facility in Germany will define Europe as a new market. Ex-US sipuleucel-T availability depends on pending regulatory approval and overseas manufacturing infrastructure, before the hurdle of practical pricing can be addressed.

Disconnecting from the trial environment

For formal clinical trials, adherence to selection criteria is rigidly enforced, under the authority of scientific, regulatory, and institutional review boards (IRB); this is particularly so for a registration trial. The market experience is different. Clinical heterogeneity in a real life oncology practice is substantial. For those individuals who would seem to be “beyond” the usual trial entry point, and thus, closer to death from disease, the compelling question is “why not now?” The safety experience did show a worse stroke event rate (23/338 vs 3/168), which is still being evaluated in a post-marketing setting. The short term acute side effects of sipuleucel-T infusion are few, and the medical risk/benefit balance may still be positive for the vast majority of patients.

For those who are at a point in the disease course where the pivotal trial criteria would not be met, there is the question: why should one be left “to ripen” until bad enough to meet criteria? On a theoretical immunologic basis, an individual at an earlier point in the disease should have a better amplitude response, and maybe, better survival prospects. Empiric data on this issue of optimal timing are lacking. Some examples, drawn loosely from actual patient discussions, are organized in .

Table 2 Examples of real life heterogeneity vs clinical trial criteria

Some patients will express an interest in sipuleucel-T therapy prior to testosterone suppression. This interest does not mean that the person misunderstood the selection criteria of the original trial, nor a conceptual difference on the understanding of hormone-sensitive versus refractory disease. It is, rather, a reflection of the heterogeneity of contemporary belief about the extent to which a rational, rather than strictly empiric, interpretation of new trial data should be used. Again, direct empiric data on this point are lacking.

Education about the process of treatment

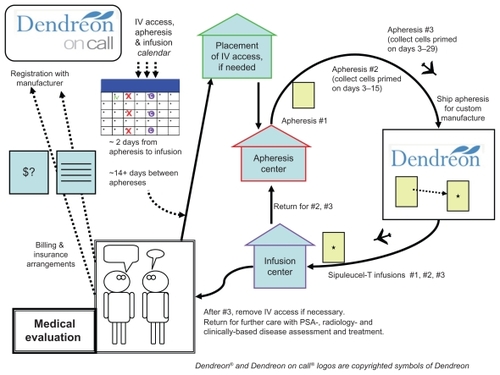

The chronology of a standard on-label treatment is annotated in . The manufacturer’s website (www.provenge.com) has a patient-directed video reviewing the process as well. There are a few points that merit emphasis in educating the patient about the treatment process, since it is so different from a conventional drug treatment.

Figure 1 Diagram of the treatment process. Starting in the lower left, is a patient consultation and medical evaluation. Continuing (upwards), registration with the Dendreon On Call program and defining practical third party payer issues. A treatment calender with line-placement (if needed), and three apheresis dates, each followed by infusion dates is developed. From there, the patient has a line placement (if needed), then 3 cycles of apheresis and infusion (illustrated by the clockwise arrows on the right). After the third infusion, the patient returns for consultation and further disease management.

The big first step is patient selection. Next is apheresis: the manufacturer has a defined set of approved leukapheresis locations, and these may be quite a distance from the patient or the medical practice where the infusion is to take place. Since the apheresis bag is shipped out directly to the manufacturer, and then back to the infusion location, no transportation of any of the cellular material is by the patient; the patient must show up at the right places and times. The manufacturer’s schedule coordination program (“Dendreon On Call”) will set times for the collections and infusions; adherence to the schedule must be stressed. The apheresis center will also give guidance for the required caliber of intravenous access, which may vary based on available equipment. Some individuals will be able to use a pair of 16 gauge needles, placed at the center at the time of collection, but others, with marginal useful venous access, may require a separate placement of a vascular access device, such as a Hohn catheter, which will be in place for the entire month of the treatment and require periodic maintenance flushes. The leukapheresis process may take a couple of hours.

For each of the three infusions, the planned infusion time is 60 minutes, followed by at least 30 minutes observation. Each individual’s identity must be verified, and the specific quality control assessment completed. There is no assessment for viral infections, underscoring the need for strictly autologous administration. If a quality control problem (for example cell count or bacterial contamination) were identified at a late point then that product must be set aside, and that portion of the apheresis/infusion cycle would need to be rescheduled. The window of time for the infusion is defined in strict terms, with only 3 hours allowed after removal from the shipping container, and a product expiration time specified based on the shipping time. A significant part of the shelf life could elapse during the shipping process, particularly if airport delays occur.

Patient information about side effects (as annotated at www.provenge.com) emphasize a high frequency of low grade chills (53%) fatigue (41%) and fever (31%) as well as 20%–30% with joint aches, nausea, or back aches.Citation70 Chills may result directly from the infusion of the 250 mL of cooled lactated Ringer’s, in which the cells are suspended (the sipuleucel-T should not be warmed, nor returned to the shipping container, but the patient may have a blanket). Delayed symptoms, such as from heart or lung reactions, should be managed directly, and considered to be potentially signs of infection.

Contrasting with other kinds of treatment

Referring to , the step designated as the return to clinical consultation is a very real-world issue. After a month or so devoted to sipuleucel-T treatment, the clinician and the patient are back to the same treatment planning issues that brought them to the point of the sipuleucel-T prescription. The administration of docetaxel after sipuleucel-T was relatively frequent in the pivotal trial experience. This does provide a specific base of experience for that sequence of treatment, although docetaxel itself was not, in a retrospective analysis, a factor on which the survival increment of sipuleucel-T was dependent.Citation99

Beyond this, there is little specific guidance on a next active therapy. Outside a clinical trial, the reality is that no one individual could reliably discern a treatment effect, since the endpoint is overall survival. This may be an ongoing contrast with newer hormone therapies (such as MDV3100 or abiraterone), other immunotherapies or newer chemotherapies, all of which may afford some early, accessible feedback, such as PSA levels. Patient acceptance of the concept of an isolated overall survival impact may be a moving target, influenced by features of other drugs, both in the immunotherapy and nonimmunotherapy classes.

Conclusion

Cancer immunotherapy achieved an important milestone with US FDA approval of sipuleucel-T. This cellular immunotherapy is a safe treatment option for prostate cancer, tested in minimally symptomatic CRPC patients with a median OS benefit of 4.1 months. Despite the lack of immediately evident antitumor effects, sipuleucel-T represents an exciting prototype for future, more beneficial treatments with greater disease impact. From the early phase trials to the pivotal placebo-control trial with sipuleucel-T,Citation71,Citation73,Citation77 the immunological outcomes, particularly the rising titer of antibodies with specificity to PA2024 and CTL titers, suggest that further understanding can lead to amplification of the immunologic effect and clinical benefit.Citation67 Even though sipuleucel-T trial data shows a survival improvement that is limited and comparable in size to benefits obtained with standard agents approved for this population,Citation30,Citation31 and cabazitaxel,Citation35 it does not have the potential toxicity of chemotherapy. Newer hormone-type therapies also have been shown to offer similar magnitude survival benefits (14.8 vs 10.9 months for abiraterone).Citation45

However, even as sipuleucel-T is the gateway to an exciting new paradigm, the novel treatment still leaves unmet needs. The pivotal trial population was a narrowly defined one. Further studies are needed to determine other target populations, such as hormone sensitive disease, or subpopulations defined by immunological parameters. These groups of men might be better candidates for immunotherapy, and a clinical response to immune modulation could be more clinically rewarding.

At this time, during the early use and expanding acceptance of sipuleucel-T, it is imperative to optimize the role and timing of sipuleucel-T for prostate cancer patient therapy. New agents both in hormone therapy and immunotherapy may also be expected to be part of a changing landscape for CRPC treatment. Sequencing and patient selection will be an evolving process, and we can be hopeful that more clinical trial participation will make sipuleucel-T a starting point for more quantitatively-effective, cost-effective, well-tolerated treatment for the prostate cancer community.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- National Cancer InstituteCancer of the prostate. SEER Sata Fact Sheets Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.htmlAccessed June 3, 2011

- GuralnikJMLaCroixAZEverettDFAging in the eighties: the prevalence of comorbidity and its association with disabilityAdvance Data17019898 Publication No. PHS 89–1250

- YancikRCancer burden in the aged: an epidemiologic and demographic overviewCancer1997807127312839317180

- KattanMWWheelerTMScardinoPTPostoperative nomogram for disease recurrence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancerJ Clin Oncol19991751499150710334537

- JemalASiegelRWardECancer statisticsCA Cancer J Clin20106027730020610543

- PowellIJEpidemiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer in African-American menJ Urol2007177244444917222606

- ParisPLKupelianPAHallJMAssociation between a CYP3A4 genetic variant and clinical presentation in African-American prostate cancer patientsCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev199981090190510548319

- WiltTJMacDonaldRRutksIShamliyanTATaylorBCKaneRLSystematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancerAnn Intern Med2008148643544818252677

- ZeliadtSBRamseySDPensonDFWhy do men choose one treatment over another?: a review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancerCancer200610691865187416568450

- FowlerFJJrMcNaughton CollinsMAlbertsenPCComparison of recommendations by urologists and radiation oncologists for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancerJAMA2000283243217322210866869

- TolisGAckmanDStellosATumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonistsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1982795165816626461861

- KlotzLBoccon-GibodLShoreNDThe efficacy and safety of degarelix: a 12-month, comparative, randomized, open-label, parallel-group phase III study in patients with prostate cancerBJU Int2008102111531153819035858

- ShoreNDMoulJWCrawfordEProstate-specific antigen (PSA) progression-free survival (PFS): a comparison of degarelix versus leuprolide in patients with prostate cancerJ Clin OncolGenitourinary Cancers Symposium201129Suppl 7 Abstr 12

- van AndelGKurthKHThe impact of androgen deprivation therapy on health related quality of life in asymptomatic men with lymph node positive prostate cancerEur Urol200344220921412875940

- WilkeDRParkerCAndonowskiATestosterone and erectile function recovery after radiotherapy and long-term androgen deprivation with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonistsBJU Int200697596396816542340

- LoblawDAVirgoKSNamRInitial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guidelineJ Clin Oncol200725121596160517404365

- BalesGTChodakGWA controlled trial of bicalutamide versus castration in patients with advanced prostate cancerUrology199647Suppl 1A38438560677

- KassoufWTanguaySAprikianAGNilutamide as second line hormone therapy for prostate cancer after androgen ablation failsJ Urol200316951742174412686822

- WhitakerHCHanrahanSTottyNAndrogen receptor is targeted to distinct subcellular compartments in response to different therapeutic antiandrogensClin Cancer Res200410217392740115534116

- AkakuraKBruchovskyNGoldenbergSLRenniePSBuckleyARSullivanLDEffects of intermittent androgen suppression on androgen-dependent tumors. Apoptosis and serum prostate-specific antigenCancer1993719278227907682149

- Boccon-GibodLHammererPMadersbacherSMottetNPrayer- GalettiTTunnUThe role of intermittent androgen deprivation in prostate cancerBJU Int2007100473874317662079

- KlotzLHHerrHWMorseMJWhitmoreWFIntermittent endocrine therapy for advanced prostate cancerCancer19865811254625502429759

- GoldenbergSLBruchovskyNGleaveMEIntermittent androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer: a preliminary reportUrology1995455839844 discussion 44–457538246

- CrookJMSzumacherEMaloneSHuanSSegalRIntermittent androgen suppression in the management of prostate cancerUrology199953353053410096379

- KlotzLO’CallaghanCJDingKA phase III randomized trial comparing intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for patients with PSA progression after radical therapy: NCIC CTG PR.7/SWOG JPR.7/CTSU JPR.7/UK Intercontinental Trial CRUKE/01/013J Clin Oncol201129Suppl 7 Abstr 3

- TunnUEckartOKienleECan intermittent androgen deprivation be an alternative to continuous androgen withdrawal in patients with PSA relapse? First results of the randomized prospective phase III clinical trial EC 507J Urol2003169Suppl 41481a

- SmallEJVogelzangNJSecond-line hormonal therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a shifting paradigmJ Clin Oncol19971513823888996165

- SmallEJHalabiSDawsonNAAntiandrogen withdrawal alone or in combination with ketoconazole in androgen-independent prostate cancer patients: a phase III trial (CALGB 9583)J Clin Oncol20042261025103315020604

- NishimuraKNonomuraNYasunagaYLow doses of oral dexamethasone for hormone-refractory prostate carcinomaCancer200089122570257611135218

- PetrylakDPTangenCMHussainMHDocetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancerN Engl J Med2004351151513152015470214

- TannockIFde WitRBerryWRDocetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancerN Engl J Med2004351151502151215470213

- BertholdDRPondGRSobanFdeWitREisenbergerMTannockIFDocetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: updated survival in the TAX 327 studyJ Clin Oncol200826224224518182665

- BerryWDakhilSModianoMGregurichMAsmarLPhase III study of mitoxantrone plus low dose prednisone versus low dose prednisone alone in patients with asymptomatic hormone refractory prostate cancerJ Urol200216862439244312441935

- TannockIFOsobaDStocklerMRChemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end pointsJ Clin Oncol1996146175617648656243

- de BonoJSOudardSOzgurogluMPrednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trialLancet201037697471147115420888992

- KellyWKHalabiSCarducciMAA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel, prednisone, and placebo with docetaxel, prednisone, and bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): survival results of CALGB 90401J Clin Oncol201028Suppl 18LBA4511

- SternbergCNPetrylakDPSartorOMultinational, double-blind, phase III study of prednisone and either satraplatin or placebo in patients with castrate-refractory prostate cancer progressing after prior chemotherapy: the SPARC trialJ Clin Oncol200927325431543819805692

- ScherHIBeerTMHiganoCSAntitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase1–2 studyLancet201037597241437144620398925

- O’DonnellAJudsonIDowsettMHormonal impact of the 17alpha-hydroxylase/C(17,20)-lyase inhibitor abiraterone acetate (CB7630) in patients with prostate cancerBr J Cancer200490122317232515150570

- PotterGABarrieSEJarmanMNovel steroidal inhibitors of human cytochrome P45017 alpha (17 alpha-hydroxylase-C17,20-lyase): potential agents for the treatment of prostatic cancerJ Med Chem19953813246324717608911

- AttardGReidAHA’HernRSelective inhibition of CYP17 with abiraterone acetate is highly active in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancerJ Clin Oncol200927233742374819470933

- DanilaDCMorrisMJde BonoJSPhase II multicenter study of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy in patients with docetaxel-treated castration-resistant prostate cancerJ Clin Oncol20102891496150120159814

- ReidAHAttardGDanilaDCSignificant and sustained antitumor activity in post-docetaxel, castration-resistant prostate cancer with the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetateJ Clin Oncol20102891489149520159823

- de BonoJSLogothetisCFizaziKAbiraterone acetate plus low dose prednisone improves overall survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have progressed after docetaxel-based chemotherapy: results of COU-AA-301, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Phase III studyAnn Oncol201021LBA5

- MolinaABelldegrunANovel therapeutic strategies for castration resistant prostate cancer: inhibition of persistent androgen production and androgen receptor mediated signalingJ Urol2011185378779421239012

- BodeCJGuptaMLJrReiffEAEpothilone and paclitaxel: unexpected differences in promoting the assembly and stabilization of yeast microtubulesBiochemistry200241123870387411900528

- LinAMRosenbergJEWeinbergVKClinical outcome of taxane resistant hormone refractory prostate cancer patients treated with subsequent chemotherapy (ixabepilone (Ix) or mitoxantrone/prednisone (MP))Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol200624Suppl231s

- DrakeCGAntonarakisESUpdate: immunological strategies for prostate cancerCurr Urol Rep201011320220720425628

- MoonCParkJCChaeYKYunJHKimSCurrent status of experimental therapeutics for prostate cancerCancer Lett2008266211613418440696

- WangXYuJSreekumarAAutoantibody signatures in prostate cancerN Engl J Med2005353121224123516177248

- PalenaCSchlomJVaccines against human carcinomas: strategies to improve antitumor immune responsesJ Biomed Biotechnol2010201038069720300434

- BanchereauJSteinmanRMDendritic cells and the control of immunityNature199839266732452529521319

- FishmanMA changing world for DCvax: a PSMA loaded autologous dendritic cell vaccine for prostate cancerExpert Opin Biol Ther20099121565157519916735

- ZhangHMelamedJWeiPConcordant down-regulation of proto-oncogene PML and major histocompatibility antigen HLA class I expression in high-grade prostate cancerCancer Immun20033212747744

- SandaMGRestifoNPWalshJCMolecular characterization of defective antigen processing in human prostate cancerJ Natl Cancer Inst19958742802857707419

- ZhangLGajewskiTFKlineJPD-1/PD-L1 interactions inhibit antitumor immune responses in a murine acute myeloid leukemia modelBlood200911481545155219417208

- AhmadzadehMJohnsonLAHeemskerkBTumor antigen-specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impairedBlood200911481537154419423728

- ChappellDBRestifoNPT cell-tumor cell: a fatal interaction?Cancer Immunol Immunother199847265719769114

- CurtiATrabanelliSSalvestriniVBaccaraniMLemoliRMThe role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the induction of immune tolerance: focus on hematologyBlood2009113112394240119023117

- FukumuraDKashiwagiSJainRKThe role of nitric oxide in tumour progressionNat Rev Cancer20066752153416794635

- LahdenrantaJHagendoornJPaderaTPEndothelial nitric oxide synthase mediates lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasisCancer Res20096972801280819318557

- SmallEJFratesiPReeseDMImmunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with antigen-loaded dendritic cellsJ Clin Oncol200018233894390311099318

- BanchereauJSteinmanRMDendritic cells and the control of immunityNature199839266732452529521319

- BurchPABreenJKBucknerJCPriming tissue-specific cellular immunity in a phase I trial of autologous dendritic cells for prostate cancerClin Cancer Res2000662175218210873066