Abstract

Purpose

The survival benefit from gemcitabine plus erlotinib was on average marginal for advanced pancreatic cancer (APC) patients. Skin rash developed shortly after starting treatment seemed to be associated with better efficacy and might be used to assist clinical decision-making, but the results across studies were inconsistent. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, three Chinese databases, and the abstracts of important conferences were searched for eligible studies. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), and the secondary outcomes were progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response. The random-effects model was used to pool results across studies if heterogeneity was substantial. Otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used.

Results

A total of 16 studies with 1,776 patients were included. Patients who developed skin rash during treatment had longer OS (8.9 vs 4.9 months, HR=0.57, 95% CI 0.50–0.64) and longer PFS (4.5 vs 2.4 months, HR=0.53, 95% CI 0.40–0.68) than those who did not. A dose– response relationship was also observed for both OS (HR=0.64 for grade-1 rash vs no rash and HR=0.46 for ≥grade-2 rash vs no rash) and PFS (HR=0.72 for grade-1 rash vs no rash and HR=0.43 for ≥grade-2 rash vs no rash).

Conclusion

Skin rash was associated with better OS and PFS in APC patients treated with gemcitabine plus erlotinib. It might be used as a marker for efficacy to guide clinical decision-making toward a more precise and personalized treatment.

Introduction

As a highly malignant disease, pancreatic cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, including the US, the UK, and Hong Kong.Citation1–Citation3 More than 80% of patients are diagnosed when the cancer is already at a locally advanced or metastatic stage, which is often referred to as advanced pancreatic cancer (APC).Citation2 Without adequate treatment, the median survival of these patients is only ~3–5 months.Citation4 For years, gemcitabine has been the standard treatment of APC.Citation5 However, its benefit is small, with an increase of only 1.2 months in overall survival (OS).Citation6 Recently, three regimens, namely gemcitabine plus erlotinib (6.24 vs 5.91 months, P=0.038),Citation7 gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (8.5 vs 6.7 months, P<0.001),Citation8 and combination therapy of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFIRINOX; 11.1 vs 6.8 months, P<0.001),Citation9 were proved to be able to achieve longer survival as compared with gemcitabine alone.

Although the survival benefit provided by gemcitabine plus erlotinib is less than that by gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel or FOLFIRINOX, this regimen is associated with much fewer severe (grade 3 or grade 4) adverse events as compared with the other two regimens.Citation7–Citation9 In fact, the adverse events induced by gemcitabine plus erlotinib are mostly mild or moderate (grade 1 or grade 2).Citation7 Interestingly and more importantly, it seems that those who are thus treated and develop skin rash during the treatment could achieve a significantly longer survival than those without skin rash. For example, Aranda et alCitation10 found that the median survival with gemcitabine plus erlotinib was 3.3, 6.6, and 10.3 months in patients who developed no rash, grade-1 rash, and ≥grade-2 rash, respectively (P<0.001). Similar results were shown by Moore et al.Citation7 In the study of Beveridge et al,Citation11 the benefit was even larger (5.2 vs 12.0 months for rash vs no rash, P=0.025). This relationship was also observed in patients with other cancers treated with erlotinib.Citation12,Citation13 These findings suggested that skin rash could be a useful marker for predicting the efficacy of gemcitabine plus erlotinib and informing treatment decision.

However, the findings of existing studies regarding the role of skin rash seem inconsistent. For example, in some studies, the median survival time of patients with rash was longer than that of patients without rash,Citation11 while in others, it was the other way round.Citation14 Some suggested that rash could be a useful marker to inform choice of treatment,Citation7,Citation10,Citation11 while others disagreed and even stated that “decision for interruption or maintenance of GEM + E, therefore, should not be based on the rash phenomenon”.Citation14,Citation15 Importantly, many studies had small sample size, and their results were statistically insignificant.Citation14–Citation20 Could the discrepancy between the studies be explained merely by chance or different sample sizes? Alternatively, could effect modifiers such as some clinical characteristics play important roles, so that skin rash is truly not associated with prolonged survival in some populations? The answer is yet to be explored. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize existing evidence on the association of skin rash with clinical outcomes in APC patients treated with gemcitabine plus erlotinib.

Materials and methods

Data sources and literature search

We performed a systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, China Biology Medicine (in Chinese), Wanfang Data (in Chinese), and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (in Chinese) from inception through 16 August 2017 using the following key words and their synonyms or their Chinese counterparts: pancrea*, cancer*, carcinoma*, adenocarcinoma*, tyrosine kinase inhibitor*, erlotinib, tarceva, OSI-774, and OSI774. As analysis on the relationship between skin rash and clinical outcomes might not be the major interest of some potentially eligible studies, the terms related to skin rash may not appear in their searchable fields, and thus, we did not use those terms in literature search. There were no restrictions on language or publication status (abstracts and full text) of studies. Wherever possible, the searches were limited to “human studies”. To supplement the search of electronic databases, the meeting abstracts of American Society of Clinical Oncology and European Society of Medical Oncology were reviewed manually.

Study selection

Two reviewers (MZ and QF) screened the records’ titles and abstracts independently to judge their relevance to this systematic review. Full texts of the studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria listed earlier were obtained for further examination. Potentially eligible studies selected by the two reviewers were then combined and discussed for final decision on their eligibility. Studies that fulfilled all the following criteria were considered as eligible for this systematic review: 1) study participants were patients diagnosed with APC; 2) the patients were treated with gemcitabine plus erlotinib; 3) at least one of the following clinical outcomes were assessed: OS (the time from start of treatment to death or loss of follow-up, whichever occurred first), progression-free survival (PFS; the time from start of treatment to radiological progression or loss of follow-up, whichever occurred first), and objective response assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors or its updated versions; 4) skin rash was assessed according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTCAE), its updated versions, or others (such as WHO Toxicity Criteria [WHO-TC]); and 5) the relationship between skin rash and clinical outcomes was assessed. The reference lists of eligible studies and relevant reviews were also scrutinized for additional eligible studies. If two or more reports were available from one study, either some of them were excluded or they were combined to get a full picture of the study, depending on the extent of duplication (complete or partial).

Data extraction

After eligible studies were identified, the following data were extracted from the study: 1) bibliographic information, such as the first author, country, and publication year; 2) baseline clinical characteristics of patients, such as the number of patients with rash and those without, age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) level, pathological type and treatment; 3) main numerical results, such as HRs and 95% CIs for OS and PFS, ORs and 95% CIs for objective response, and other data from which the effect estimates could be calculated; and 4) information on methodological quality (see in the following).

Authors of original studies were contacted as needed to clarify ambiguities in reported methods or results and to seek additional data omitted in the publications. If not explicitly reported in original publications and still not available after contacting with the author, HRs were estimated using the method developed by Parmar et al,Citation21 which was recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews.Citation21 Data were extracted independently by two reviewers (MZ and QF) using a standardized data extraction form. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by revisiting original publications and discussion until consensus was reached.

Risk of bias assessment

All eligible studies could be viewed as cohort studies in terms of their methodological rigor, as the comparison of rash with no rash was and could only be observational. Since no gold standard was available for methodological quality assessment of cohort studies, Newcastle–Ottawa ScaleCitation22 was adopted in the present systematic review, which has been frequently used in other systematic reviews. This scale focuses on three study aspects, including selection of patients, comparability of baseline characteristics between comparison groups, and outcome assessment. For each aspect, there were up to four items for detailed evaluation. The overall study quality was denoted by a numerical score ranging from 0 to 9, with 7–9 scores indicating good quality. Quality assessment was performed independently by two reviewers (MZ and QF). Disagreements between the two were resolved by revisiting original papers and discussing. Unresolved disagreements were referred to a third expert researcher (ZY) for a final decision.

Data synthesis and analysis

The primary clinical outcome of this study was OS, and the secondary outcomes included PFS and objective response. The clinical outcomes were compared between patients with rash vs those without and between patients with high-grade (≥grade 2) rash vs those with low-grade rash (≤grade 1). The difference in OS or PFS between groups was measured by HR with 95% CI, and the difference in objective response was measured by OR with 95% CI. HRs and ORs from relevant studies were combined to produce a summary HR and OR, respectively. HR <1 or OR >1 meant the outcomes of those with skin rash during treatment were better than those without, while HR >1 or OR <1 meant the opposite. To provide clinicians and patients with more intuitive and straightforward information for their decision-making, we also synthesized the median survival times for the rash (and high-grade rash) group and the no-rash (and low-grade rash) one, respectively, using the method proposed by Zang et al.Citation23 We also investigated dose–response relationship, the phenomenon that the probability of outcome (ie, OS and PFS in this systematic review) increases or decreases with the dose/level of exposure (ie, different grades of rash in this systematic review) by comparing the pooled effect estimate of grade-1 skin rash vs no rash with the pooled effect estimate of ≥grade 2 skin rash vs no rash.

Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed by the Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic.Citation24 A P-value ≤0.10 for the Q test or an I2 value >50% was suggestive of significant heterogeneity. If there was no significant heterogeneity, data from different studies will be pooled with the fixed-effects model. Otherwise, the random-effects model was used for pooling results and subgroup analyses were used to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity according to selected clinical factors such as ethnicity, performance status, and prior chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer. If suitable data on the time from starting treatment to onset of skin rash were available, subgroup analysis according to the time would be conducted. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding the studies according to two aspects, including methodological (eg, excluding the studies with low-quality score) and clinical characteristics (eg, excluding the studies that recruited a small number of patients receiving an additional therapy during the treatment). Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to examine publication bias.Citation25 However, the two tests were conducted only when a meta-analysis included more than 10 studies and no substantial heterogeneity was observed among the studies; otherwise, the tests would have limited statistical power and misleading results.Citation25,Citation26 In presence of an asymmetric funnel plot, the Duval and Tweedie nonparametric trim-and-fill method was used to adjust for the potential reporting bias and obtain an adjusted result of meta-analysis.Citation27 The synthesis of median survival times was conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and the other analyses were performed using STATA (version 11.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

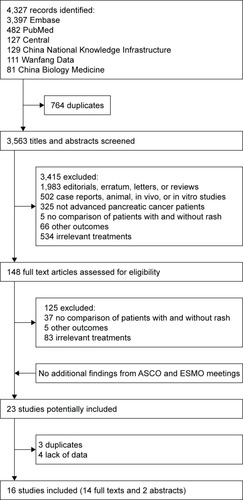

As shown in , ,327 records were retrieved by literature search and 16 studies with 1,776 patients were finally included in this systematic review.Citation10,Citation11,Citation14,Citation18,Citation28–Citation39 The characteristics of eligible studies are given in . In all, 12 studies were prospective and four retrospective. Eight studies were performed predominantly in Caucasians and seven in Asians. A total of 12 studies assessed skin rash according to the NCI-CTCAE and two according to the WHO-TC. The median/mean age reported by different studies ranged from 55.0 to 67.2 years (median: 63.9 years). The proportions of male patients ranged from 41.7% to 72.7% (median: 57.5%). The proportions of patients with relatively good performance status (ECOG PS 0–1) ranged from 59.4% to 100% (median: 86.1%). A total of 10 studies reporting histology enrolled only or mostly (≥90%) patients with exocrine tumors. In 10 of the 12 studies reporting prior chemotherapy treatment, all or most (>90%) of the patients were treatment naïve. Data on OS, PFS, and objective response were provided by 12, nine, and eight studies, respectively. In all, 12 studies were assessed as with a low risk of bias (). In the process of data extraction and quality assessment, six disagreements occurred between the two reviewers (four in quality assessment and two in data extraction), but none of the disagreements was about the data of key results and all were resolved after discussion. Thus, they did not influence our main analyses.

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies included for analysis

Figure 1 Flowchart of study selection.

OS

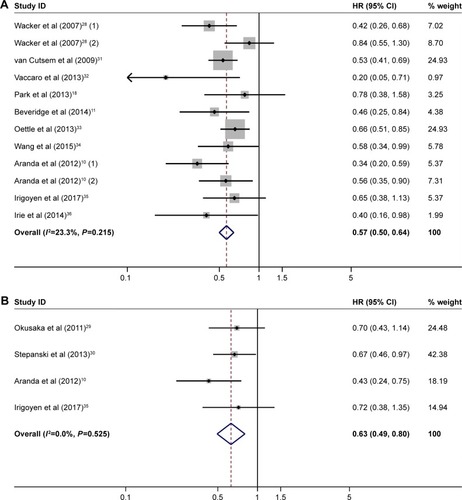

A total of 10 studies with 1,421 patients reported comparison of OS between the patients with rash and those without, and the pooled median OS time of them was 8.9 and 4.9 months, respectively (HR=0.57, 95% CI 0.50–0.64, heterogeneity I2=23.3%, P=0.215; ). Four studies with 487 patients reported comparison between the patients with high- and low-grade rash (HR=0.63, 95% CI 0.49–0.80, heterogeneity I2=0.0%, P=0.525; ). As severity of rash increased, the association of rash with OS became stronger (grade-1 rash vs no rash: HR=0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.88, heterogeneity I2=60.7%, P=0.054; grade-2 rash vs no rash: HR=0.46, 95% CI 0.37–0.57, heterogeneity I2=0.0%, P=0.433).

Figure 2 (A) Forest plot of HR for OS: with vs without rash. (B) Forest plot of HR for OS: high-grade rash vs low-grade rash.

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

PFS

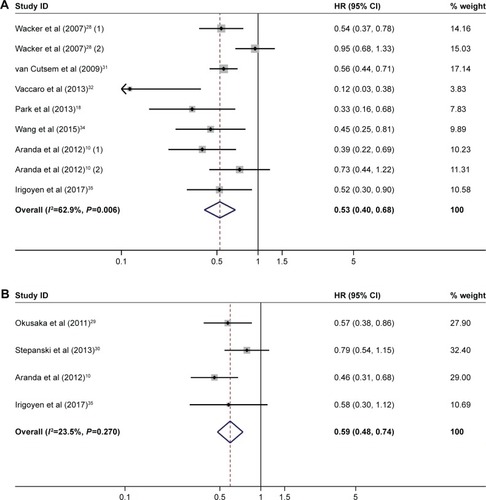

Seven studies with 927 patients compared PFS between the patients with rash and those without, and the pooled median PFS of them was 4.5 and 2.4 months, respectively (HR=0.53, 95% CI 0.40–0.68, heterogeneity I2=62.9%, P=0.006; ). A similar trend was observed in the comparison between high- and low-grade rash (HR=0.59, 95% CI 0.48–0.74, heterogeneity I2=23.5%, P=0.270; ). As severity of rash increased, the association of rash with PFS became stronger (grade-1 rash vs no rash: HR=0.72, 95% CI 0.55–0.94, heterogeneity I2=55.2%, P=0.082; grade-2 rash vs no rash: HR=0.43; 95% CI 0.35–0.53, heterogeneity I2=0.0%, P=0.781).

Figure 3 (A) Forest plot of HR for PFS: with vs without rash. (B) Forest plot of HR for PFS: high-grade vs low-grade rash.

Abbreviation: PFS, progression-free survival.

Objective response

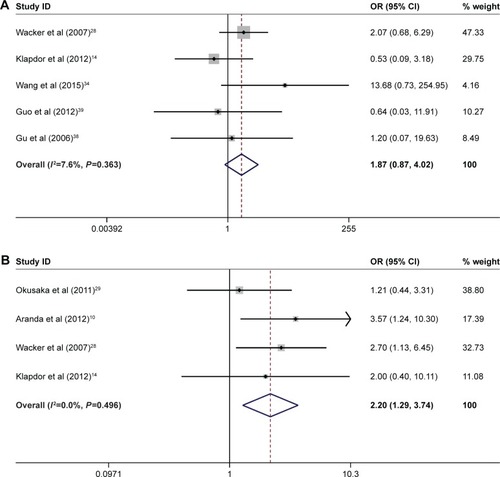

There was a trend that rash was associated with a higher likelihood of response in the comparison between rash and no rash (40/254 [15.7%] vs 9/107 [8.4%], OR=1.87, 95% CI 0.87–4.02, heterogeneity I2=7.6%, P=0.363; ) and in the comparison between high- and low-grade rash (39/202 [19.3%] vs 31/341 [9.1%], OR=2.20, 95% CI 1.29–3.74, heterogeneity I2=0.0%, P=0.496; ), consistent with the results of OS and PFS.

Figure 4 (A) Forest plot of OR for objective response: with vs without rash. (B) Forest plot of OR for objective response: high-grade rash vs low-grade rash.

Sensitivity, subgroup, and publication bias analyses

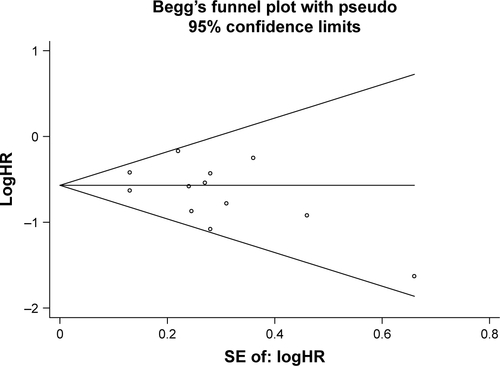

Sensitivity analyses according to methodological quality and clinical characteristics showed that the results described earlier were robust (). A series of prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the potential source of substantial heterogeneity observed in . The results showed that ECOG physical performance status and prior chemotherapy treatment might be associated with the substantial heterogeneity (). Specifically, the associations between rash and clinical outcomes were stronger in the subgroup where more patients had worse performance status (≥2) and in the subgroup where more patients were treatment naive. Only two studiesCitation10,Citation28 included in our systematic review mentioned the time from starting treatment to onset of skin rash, but they merely reported the median time instead of individual data. Owing to limited data, we did not conduct subgroup analysis according to the time of onset of skin rash. Egger’s tests for asymmetry of the funnel plot constructed based on the data of were not statistically significant (P=0.188; ), suggesting no evidence for publication bias. Potential publication bias in the data of other figures was not assessed due to the limited number of studies (<10) included in these meta-analyses.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized 16 studies with 1,776 patients and found that skin rash was significantly associated and had a dose–response relationship with longer OS and PFS in APC patients treated with gemcitabine plus erlotinib. Similar results were observed in cancers at other sites than pancreas. For example, the systematic reviews of Liu et alCitation40 and Petrelli et alCitation12,Citation41 found that skin rash was associated with longer OS and PFS and higher objective response rate in lung cancer and colorectal cancer patients, respectively. A trial of erlotinib in patients with metastatic cancer of head and neck reported a dose–response relationship between skin rash and OS.Citation13

However, it should be noted that the evidence summarized here is not the optimal for establishing the predictive role of skin rash, because it is well possible that skin rash was also associated with better outcomes in the gemcitabine–placebo arm, in which case the association was not specific to gemcitabine–erlotinib treatment, and thus, skin rash could not be used to predict the efficacy of the treatment. In epidemiology, the best design to evaluate whether a factor could predict treatment efficacy or not is randomized clinical trial with subgroup analysis according to the potential predictive factor and assessment of interaction between the factor and the treatment.Citation42 We did not conclude such evidence in the present systematic review because our pilot search showed that there was only one such trial, which was by Moore et al.Citation7 Fortunately, Moore et alCitation7 found that skin rash was significantly associated with longer OS (HR=0.74, 95% CI 0.56–0.98, P-value=0.037) in the gemcitabine–erlotinib arm but not in the gemcitabine-placebo arm (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.68–1.18, P-value=0.435),Citation28 suggesting that rash could predict the efficacy of gemcitabine–erlotinib treatment and thus supporting the findings of the present systematic review.

The association between skin rash and clinical outcomes may be explained by the following biological mechanisms. Erlotinib is a small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR, which is frequently overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and associated with the progression of the disease.Citation43 However, as EGFR is also expressed as undifferentiated and proliferating keratinocytes in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epidermis, the therapeutic effects of erlotinib may at the same time cause growth arrest and inflammation of epidermis that ultimately lead to skin rash.Citation44,Citation45 Patients who constantly have a high plasma drug concentration are more likely to develop skin rash.Citation46 This is supported by two RCTs that reported that the appearance of rash was positively associated with the concentration of erlotinib.Citation47,Citation48 In fact, skin rash in the form of clustering pustular lesions on the face, neck, and upper body is the earliest, commonest and most characteristic adverse effect of EGFR-targeted drugs including erlotinib.Citation7,Citation12,Citation49

Compared with objective response assessed by imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) and X-ray,Citation50 skin rash is straightforward and easier to evaluate without introducing additional harms and costs.Citation51 Furthermore, skin rash usually occurs within 8 days of starting the treatment, with maximal intensity in the second week,Citation49 while the result of objective response assessment according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors guidelines is usually not available until 6–8 weeks after starting treatment.Citation50,Citation52 Therefore, skin rash could be used to facilitate an early estimate of the efficacy of gemcitabine plus erlotinib and help clinicians and patients decide on whether to continue with the regimen or to switch to other regimens. These decisions may exempt patients suffering from unnecessary toxicity of a futile regimen, potentially save cost, and enable them to switch to other potentially effective treatments as early as possible. In addition to survival improvement, patients who develop rash during the treatment may also benefit psychologically from reassurance about the efficacy of treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review looking at the relationship between skin rash and clinical outcomes of APC patients who received gemcitabine plus erlotinib. Most studies included had a low risk of bias. In addition, sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the results were robust.

However, still there are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, as mentioned earlier, we were unable to do publication bias analysis for some of the forest plots due to limited number of studies included. Second, though subgroup analyses revealed that the substantial heterogeneity observed in some meta-analyses was possibly caused by performance status and prior chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer, caution should be taken when interpreting the results. This is because the cutoff points (proportion of patients with a specific characteristic) for defining subgroups were arbitrary, the subgroups were not distinct entities, and the number of studies was very small in some subgroups. Therefore, the possibility of false-positive results and ecological fallacy cannot be ruled out. Third, the statistical power of two studies included in our systematic review was limited and 95% CIs of effect estimates rather wide, because the two studies were very small in sample size.Citation32,Citation34 However, this is not necessarily a drawback, because meta-analysis is exactly meant to increase the statistical power of analysis and precision of results by synthesizing multiple studies with relatively small sample sizes.

Conclusion

Skin rash was associated with better clinical outcomes in APC patients treated with gemcitabine plus erlotinib. As skin rash occurs earlier and is more straightforward and easier to evaluate than other known markers without introducing additional harms and costs, it could be used to facilitate an early estimate of the efficacy of gemcitabine plus erlotinib and guide clinical decision-making toward a more precise and personalized treatment.

Author contributions

Minyan Zeng was involved in study design, collection and analysis of data, and draft writing. Qi Feng carried out study design, collection and analysis of data, and critical revision of manuscript. Ming Lu performed study design, funding acquisition, and critical revision of manuscript. Jun Zhou contributed toward study design, funding acquisition, and critical revision of manuscript. Zuyao Yang was involved in study conception and design, funding acquisition, collection and analysis of data, and critical revision of manuscript. Jinling Tang carried out study design, funding acquisition, and critical revision of manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Abbreviations

| APC | = | Advanced pancreatic cancer |

| FOLFIRINOX | = | combination therapy of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin |

| NCI-CTCAE | = | National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria |

| WHO-TC | = | WHO Toxicity Criteria |

| ECOG PS | = | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status. |

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Health and Medical Research Fund (Ref No 14152141), Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 Funnel plot based on the data of (HR for OS with versus without rash).

Table S1 Quality assessment of included studies by the Newcastle–Ottawa scale

Table S2 Sensitivity analyses

Table S3 Subgroup analyses

References

- ArandaEManzanoJLRiveraFPhase II open-label study of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine in unresectable and/or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: relationship between skin rash and survival (Pantar study)Ann Oncol20122371919192522156621

- BeveridgeRDAlcoleaVAparicioJManagement of advanced pancreatic cancer with gemcitabine plus erlotinib: efficacy and safety results in clinical practiceJOP2014151192424413779

- KlapdorRKlapdorSBahloMCombination therapy with gemcitabine (GEM) and erlotinib (E) in exocrine pancreatic cancer under special reference to RASH and the tumour marker CA19-9Anticancer Res20123252191219722593509

- ParkSChungMJParkJYPhase II trial of erlotinib plus gemcitabine chemotherapy in korean patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and prognostic factors for chemotherapeutic responseGut Liver20137561161524073321

- WackerBNagraniTWeinbergJWittKClarkGCagnoniPJCorrelation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studiesClin Cancer Res200713133913392117606725

- OkusakaTFuruseJFunakoshiAPhase II study of erlotinib plus gemcitabine in Japanese patients with unresectable pancreatic cancerCancer Sci2011102242543121175992

- StepanskiEJReyesCWalkerMSThe association of rash severity with overall survival: findings from patients receiving erlotinib for pancreatic cancer in the community settingPancreas2013421323622699203

- van CutsemEVervenneWLBennounaJPhase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200927132231223719307500

- VaccaroVBriaESperdutiIFirst-line erlotinib and fixed dose-rate gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancerWorld J Gastroenterol201319284511451923901226

- OettleHTessenHGroschekMNon-interventional study with Erlotinib/Gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancerOnkologie Conference201336Supplement 7123

- WangJPWuCYYehYCErlotinib is effective in pancreatic cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: a randomized, open-label, prospective trialOncotarget2015620181621817326046796

- IrigoyenAGallegoJGuillén PonceCGemcitabine-erlotinib versus gemcitabine-erlotinib-capecitabine in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: Efficacy and safety results of a phase IIb randomised study from the Spanish TTD Collaborative GroupEur J Cancer201775738228222309

- IrieKUenoMKobayashiSGoudaYOhkawaSManabuMThe biomarkers of gemcitabine and erlotinib treatment in advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol2014323_suppl35824366938

- ChengYJBaiCMZhangZJEfficacy of Gemcitabine Combined with Erlotinib in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic CancerActaCTA Academiae Medicinae Sinica2010324421423

- GuYHShuYQHuangPWZhuWYZhuCJLiWObservation of Erlotinib (Tarceva) combined with gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomaChin Clin Oncol2006117515517

- GuoXDXuWSunCHClinical effect of Erlotinib plus gemcitabine in treatment of advanced pancreas cancerChin J of Clinical Rational Drug Use201252B2122

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SiegelRLMillerKDJemalACancer Statistics, 2017Ca-Cancer J Clin 20172017671730

- Bond-SmithGBangaNHammondTMImberCJPancreatic adenocarcinomaBMJ201234416e247622592847

- RegistryHKCHong Kong Cancer Statistics2015 Available from: http://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/Summary%20of%20CanStat%202015.pdfAccessedJanuary 17, 2018

- WilkowskiRWolfMHeinemannVPrimary advanced unresectable pancreatic cancerRecent Results Cancer Res2008177799318084950

- ChanSLChanSTChanEHHeZXZxHSystemic treatment for inoperable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: review and updateChin J Cancer201433626727624472302

- BurrisHA3rdMooreMJAndersenJImprovements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trialJ Clin Onco199715624032413

- MooreMJGoldsteinDHammJErlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials GroupJ Clin Oncol200725151960196617452677

- von HoffDDErvinTArenaFPIncreased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabineN Engl J Med2013369181691170324131140

- ConroyTDesseigneFYchouMFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancerN Engl J Med2011364191817182521561347

- ArandaEManzanoJLRiveraFPhase II open-label study of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine in unresectable and/or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: relationship between skin rash and survival (Pantar study)Ann Oncol20122371919192522156621

- BeveridgeRDAlcoleaVAparicioJManagement of advanced pancreatic cancer with gemcitabine plus erlotinib: efficacy and safety results in clinical practiceJOP2014151192424413779

- PetrelliFBorgonovoKCabidduMLonatiVBarniSRelationship between skin rash and outcome in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with anti-EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a literature-based meta-analysis of 24 trialsLung Cancer201278181522795701

- SoulieresDSenzerNNVokesEEHidalgoMAgarwalaSSSiuLLMulticenter phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neckJ Clin Oncol2004221778514701768

- KlapdorRKlapdorSBahloMCombination therapy with gemcitabine (GEM) and erlotinib (E) in exocrine pancreatic cancer under special reference to RASH and the tumour marker CA19-9Anticancer Res20123252191219722593509

- RenoufDJTangPAHedleyDA phase II study of erlotinib in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic cancerEur J Cancer201450111909191524857345

- FeliuJBorregaPLeónAPhase II study of a fixed dose-rate infusion of gemcitabine associated with erlotinib in advanced pancreatic cancerCancer Chemother Pharmacol201167121522120927525

- Munoz LlarenaALopez-VivancoGRuiz de LoberaAGem-citabine (G) fixed-dose-rate infusion (FDR) plus erlotinib (E) in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (APC)J Clin Onco2011294_suppl304

- ParkSChungMJParkJYPhase II trial of erlotinib plus gemcitabine chemotherapy in korean patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and prognostic factors for chemotherapeutic responseGut Liver20137561161524073321

- OhDYLeeKWLeeKHA phase II trial of erlotinib in combination with gemcitabine and capecitabine in previously untreated metastatic/recurrent pancreatic cancer: combined analysis with translational researchInvest New Drugs20123031164117421404106

- MuñozAAzkonaEIzaEIEfficacy and safety of fixed-dose-rate infusions of gemcitabine plus erlotinib for advanced pancreatic cancerJ Anal Oncol2015414451

- ParmarMKTorriVStewartLExtracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpointsStat Med19981724281528349921604

- WellsGSheaBO’ConnellDThe Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis Available from: http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/rtamblyn/Readings%5CThe%20Newcastle%20-%20Scale%20for%20assessing%20the%20quality%20of%20nonrandomised%20studies%20in%20meta-analyses.pdfAccessed January 17, 2018

- ZangJXiangCHeJSynthesis of median survival time in meta-analysisEpidemiology201324233733823377098

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- GSe HJPT [homepage on the Internet]Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed January 17, 2018

- TangJLLiuJLJlyLMisleading funnel plot for detection of bias in meta-analysisJ Clin Epidemiol200053547748410812319

- DuvalSTweedieRTrim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysisBiometrics200056245546310877304

- WackerBNagraniTWeinbergJWittKClarkGCagnoniPJCorrelation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studiesClin Cancer Res200713133913392117606725

- OkusakaTFuruseJFunakoshiAPhase II study of erlotinib plus gemcitabine in Japanese patients with unresectable pancreatic cancerCancer Sci2011102242543121175992

- StepanskiEJReyesCWalkerMSThe association of rash severity with overall survival: findings from patients receiving erlotinib for pancreatic cancer in the community settingPancreas2013421323622699203

- van CutsemEVervenneWLBennounaJPhase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200927132231223719307500

- VaccaroVBriaESperdutiIFirst-line erlotinib and fixed dose-rate gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancerWorld J Gastroenterol201319284511451923901226

- OettleHTessenHGroschekMNon-interventional study with Erlotinib/Gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancerOnkologie Conference201336Supplement 7123

- WangJPWuCYYehYCErlotinib is effective in pancreatic cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: a randomized, open-label, prospective trialOncotarget2015620181621817326046796

- IrigoyenAGallegoJGuillén PonceCGemcitabine-erlotinib versus gemcitabine-erlotinib-capecitabine in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: Efficacy and safety results of a phase IIb randomised study from the Spanish TTD Collaborative GroupEur J Cancer201775738228222309

- IrieKUenoMKobayashiSThe biomarkers of gemcitabine and erlotinib treatment in advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol2014323_suppl35824366938

- ChengYJBaiCMZhangZJEfficacy of Gemcitabine Combined with Erlotinib in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic CancerActaCTA Academiae Medicinae Sinica2010324421423

- GuYHShuYQHuangPWObservation of Erlotinib (Tarceva) combined with gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomaChin Clin Oncol2006117515517

- GuoXDXuWSunCHClinical effect of Erlotinib plus gemcitabine in treatment of advanced pancreas cancerChin J of Clinical Rational Drug Use201252B2122

- LiuHBWuYLvTFSkin rash could predict the response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor and the prognosis for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One201381e5512823383079

- PetrelliFBorgonovoKBarniSThe predictive role of skin rash with cetuximab and panitumumab in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published trialsTarget Oncol20138317318123321777

- MaoCYangZYHuXFChenQTangJLPIK3CA exon 20 mutations as a potential biomarker for resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Oncol20122361518152522039088

- FjällskogMLLejonklouMHObergKEErikssonBKJansonETExpression of molecular targets for tyrosine kinase receptor antagonists in malignant endocrine pancreatic tumorsClin Cancer Res2003941469147312684421

- LacoutureMEMechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitorsNat Rev Cancer200661080381216990857

- JostMKariCRodeckUThe EGF receptor – an essential regulator of multiple epidermal functionsEur J Dermatol200010750551011056418

- FallerBABurtnessBTreatment of pancreatic cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapyBiologics2009341942819774209

- van CutsemELiCPNowaraEDose escalation to rash for erlotinib plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: the phase II RACHEL studyBr J Cancer2014111112067207525247318

- HidalgoMSiuLLNemunaitisJPhase I and pharmacologic study of OSI-774, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignanciesJ Clin Oncol200119133267327911432895

- GoodinSErlotinib: optimizing therapy with predictors of response?Clin Cancer Res200612102961296316707589

- EisenhauerEATherassePBogaertsJNew response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1)Eur J Cancer200945222824719097774

- DhaniNTuDSargentDJSeymourLMooreMJAlternate endpoints for screening phase II studiesClin Cancer Res20091561873188219276273

- LynchTJKimESEabyBGareyJWestDPLacoutureMEEpidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: an evolving paradigm in clinical managementOncologist200712561062117522250