Abstract

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of death globally, with the most frequent type, nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), having a 5-year survival rate of less than 20%. While platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is currently first-line therapy for advanced disease, it is associated with only modest clinical benefits at the cost of significant toxicities. In an effort to overcome these limitations, recent research has focused on targeted therapies, with recently approved agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathways. However, these agents (gefitinib, erlotinib, and bevacizumab) provide antitumor activity for only a small proportion of patients, and patients whose tumors respond inevitably develop resistance to treatment. As angiogenesis is a crucial step in tumor growth and metastasis, antiangiogenic treatments might be expected to have antitumor activity. Important targets for the development of novel antiangiogenic therapies include VEGF, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and their receptors. It is hypothesized that targeting multiple angiogenic pathways may not only improve antitumor activity but also reduce the risk of resistance. Several novel agents, such as BIBF 1120, sorafenib, sunitinib, and cediranib have shown promising preliminary activity and tolerability in Phase II studies, and results of ongoing Phase III randomized studies will be necessary to establish the potential place of these new therapies in the management of individual patients with NSCLC.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.Citation1 Nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most frequent type of lung cancer, accounting for more than 80% of lung cancer cases. As NSCLC currently has a 5-year survival rate of less than 20%,Citation2 there is clearly a need for the development of more effective therapies.

Standard first-line treatment options depend on disease and patient characteristics, and may include surgery, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, and targeted therapies.Citation3 However, surgical resection is only a curative option if diagnosis occurs at early stage I or stage II disease (). At times, surgery with or without radiation with a more limited curative potential is an option for selected stage III NSCLC patients. Chemotherapy with a platinum-based doublet regimen is currently first-line therapy for more advanced disease, but is associated with only modest clinical benefits at the cost of significant toxicities.Citation4,Citation5 Furthermore, studies have shown no survival benefit and decreased quality of life with chemotherapy combinations beyond 4–6 cycles.Citation6–Citation8 Thus, in an effort to overcome these limitations, recent research has focused on targeted therapies that may more selectively inhibit tumor cell growth while minimizing toxicity to healthy cells and tissue.

Table 1 Staging of NSCLCTable Footnotea

Currently available targeted agents for NSCLC

Currently approved targeted agents in NSCLC are limited to inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)Citation9,Citation10 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathways.Citation11 The EGFR family of receptor tyrosine kinases serve as mediators of cell signaling by extracellular growth factors, with binding of their ligands activating intracellular pathways that promote tumor growth and survival.Citation12 An activating mutation in EGFR is observed in approximately 10% of unselected Western lung cancer patients and in a higher percentage of certain NSCLC subgroups, such as nonsmokers and those of Asian ethnicity.Citation12 Reversible EGFR-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib (Iressa®; AstraZeneca; Wilmington, DE) and erlotinib (Tarceva®; Genentech; South San Francisco, CA) inhibit EGFR signaling.

Initial Phase II results with gefitinib led to approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of this agent for NSCLC. These results showed overall objective response rates (ORR) of 19% (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.5–27.3) among 105 patients with stage III/IV NSCLC receiving a dose of 500 mg/day and 18.4% (95% CI, 12.1–27.9) of 103 patients receiving 250 mg/day in one study and 10.6% (95% CI, 6.0–16.8) with both doses in another study.Citation13,Citation14 However, addition of gefitinib to standard chemotherapy failed to prolong overall survival (OS) compared with chemotherapy alone in subsequent Phase III trials.Citation15–Citation17 Based on more recent Phase III data in which OS with gefitinib was noninferior or not significantly different to that obtained with docetaxel, a taxane,Citation18 in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC who had been pretreated with platinum-based chemotherapy,Citation19,Citation20 the United States restricted treatment with gefitinib to patients who have previously benefited from it.Citation10 However, in the European Union and Asia, gefitinib remains in use for NSCLC patients with EGFR-activating mutations.Citation21

Erlotinib was approved in the United States in 2004 for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC whose disease has progressed following at least one chemotherapy regimenCitation3,Citation22 based on prolongation of OS (6.7 versus 4.7 months for placebo; hazard ratio (HR), 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58–0.85; P < 0.001) in a double-blind Phase III trial, BR21, involving 731 patients with stage IIIB/IV NSCLC.Citation23 Erlotinib was also recently approved for maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC whose disease has not progressed after 4 cycles of platinum-based therapy,Citation24 based on the SATURN trial. The SATURN Phase III trial (N = 884) showed erlotinib prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) versus placebo irrespective of EGFR mutation status (12.3 versus 11.1 weeks; HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.62–0.82; P < 0.0001).Citation25

Response rates in the gefitinib and erlotinib Phase III studies that were conducted in nonselected populations were typically around 10%, meaning that for many patients, their tumors fail to respond to these agents.Citation26–Citation28 Those who do respond to treatment eventually develop resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, due either to a secondary mutation in the EGFR gene or amplification of mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (MET), another receptor tyrosine kinase.Citation12,Citation29

The VEGF pathway controls angiogenesis, a necessary step in tumor growth, metastasis, and malignancy.Citation30 Formation of new vasculature is required for larger tumors to obtain nutrients and oxygen; otherwise, nutrient supply is limited by diffusion, slowing tumor growth.Citation31 Indeed, tumor vascularization is a prognostic indicator of disease progression in various cancers, including NSCLC.Citation32–Citation34 Thus, as tumor growth is dependent on developing and maintaining this blood supply, antiangiogenic treatments might be expected to have antitumor activity.

Bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech) is a monoclonal antibody directed against VEGF that is currently approved in combination with carboplatin, a platinum agent, and paclitaxel, a taxane, as first-line treatment of unresected, locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC.Citation35 Bevacizumab is only available for patients whose tumors have nonsquamous histology and is not recommended for patients with hemorrhage or recent hemoptysis.Citation11,Citation36,Citation37 These exclusions are based on evidence from Phase II and III clinical trials. An early Phase II study randomized 99 patients with advanced (stage IIIB/IV or recurrent) NSCLC to receive bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg or 15 mg/kg plus carboplatin and paclitaxel or chemotherapy alone.Citation36 Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg significantly prolonged time to disease progression (TTP) (7.4 versus 4.2 months with chemotherapy alone; HR, 0.57; P = 0.023) and provided a higher response rate (31.5% of 34 patients versus 18.8% of 32 patients) and a modestly increased median OS (17.7 versus 14.9 months; P = 0.63). With the lower dose of bevacizumab, TTP was 4.3 months, ORR was 28.1% of 32 patients, and OS was 11.6 months. However, fatal hemoptysis was observed in 4 of 66 patients (6%) receiving bevacizumab. The study also correlated squamous histology with an increased risk of serious pulmonary hemorrhage, as four out of six cases of life-threatening bleeding occurred in patients with squamous carcinomas.Citation36

The Phase III Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 4599 trialCitation38 evaluated bevacizumab 15 mg/kg in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in 878 chemotherapy-naive patients. Patients with squamous histology, brain metastases, inadequate organ function, clinically significant hemoptysis, or ECOG performance status >1 were excluded. The ORR was higher with bevacizumab (133 out of 381 patients, 35%) compared with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone (59 out of 392 patients, 15%; P < 0.001). The addition of bevacizumab also prolonged median OS (12.3 versus 10.3 months; HR, 0.80; P = 0.003) and PFS (6.2 versus 4.5 months; HR, 0.66; P < 0.001) compared with chemotherapy alone. Grade ≥3 (lowest possible grade of an adverse event is 1 [mild adverse event] and highest possible grade is 5 [death]) bleeding events were reported in 19 out of 427 patients receiving bevacizumab plus chemotherapy (4.4%), while eight patients (1.9%) experienced hemoptysis.Citation38 Fifteen treatment-related deaths were observed in the bevacizumab arm compared with two deaths in the carboplatin plus paclitaxel alone arm (P < 0.001), five of which were caused by hemorrhage. Evaluable patients receiving bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel (n = 427) experienced higher rates of grade 4 neutropenia (25.5% versus 16.8% in 440 patients receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel alone; P = 0.002) and thrombocytopenia (1.6% versus 0.2%; P = 0.04) as well as grade 3 febrile neutropenia (4% versus 1.8%; P = 0.02), grade 3–4 hyponatremia (3.5% versus 1.1%; P = 0.02), grade 3–4 hypertension (6.8% versus 0.5%; P < 0.001), grade 3 headache (0.5% versus 3%; P = 0.003), grade 3 rash (2.3% versus 0.5%; P = 0.02), and grade ≥3 bleeding events (0.7% versus 4.4%; P < 0.001).Citation38

In the similarly designed Phase III AVAiL trial, first-line treatment with bevacizumab 7.5 or 15 mg/kg in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine versus cisplatin and gemcitabine alone was evaluated in 1043 patients with recurrent or advanced NSCLC.Citation39 Bevacizumab prolonged PFS at both 7.5 mg/kg (6.7 versus 6.1 months for placebo; HR, 0.75; P = 0.003) and 15 mg/kg (6.5 months; HR, 0.82; P = 0.03 versus placebo),Citation39 but OS was not significantly different, possibly due to the high use of post-study second-line treatments.Citation40 The incidence of pulmonary hemorrhage was only 1.5% with bevacizumab 7.5 mg/day (5 out of 330 patients) and 0.9% with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg (3 out of 329 patients).Citation39 The rates of grade ≥3 hypertension, vomiting, neutropenia, and bleeding were numerically higher in patients who received bevacizumab than in patients who did not.

Another Phase III trial, the ATLAS study, compared bevacizumab 15 mg/kg plus erlotinib with bevacizumab alone as a maintenance therapy after 4 cycles of combined treatment with bevacizumab and platinum-based doublet chemotherapy in 768 patients with advanced NSCLC.Citation41 Patients with treated brain metastases and peripheral or extrathoracic squamous tumors were allowed to participate in this study. Preliminary efficacy results showed that the combination of erlotinib plus bevacizumab increased PFS (4.8 versus 3.7 months for bevacizumab alone; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.59–0.88; P = 0.0012) but did not significantly prolong OS (15.9 versus 13.9 months; HR, 0.90; P = 0.2686). Safety data (n = 598) have been reported for the initial chemotherapy phase of the trial.Citation42 The most common grade ≥3 adverse event was hypertension, reported for 13 out of 303 patients receiving bevacizumab with carboplatin and paclitaxel (4.3%), 9 out of 183 patients receiving bevacizumab with carboplatin and gemcitabine (4.9%), and 3 out of 112 receiving carboplatin plus docetaxel (2.7%). Grade ≥2 pulmonary or central nervous system hemorrhage each occurred in less than 2% of patients, as did grade ≥3 gastrointestinal perforations. Overall hemorrhage rates (all grades) were reported for seven patients (2.3%) with bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel, nine patients (4.9%) with bevacizumab plus carboplatin and gemcitabine, and nine patients (8%) with carboplatin plus docetaxel.

The Phase II BRIDGE study examined whether paclitaxel and carboplatin in combination with delayed bevacizumab administration would improve tolerability in patients with previously untreated squamous NSCLC; out of 31 patients treated with bevacizumab, one patient (3.2%) experienced a grade 3 pulmonary hemorrhage.Citation43 Ongoing follow-up Phase II and III trials are currently evaluating bevacizumab therapy in combination with other targeted agents as well as standard chemotherapy in both first-line and second-line settings for multiple malignancies, including NSCLC.Citation40,Citation44–Citation47 While bevacizumab is the only antiangiogenic therapy currently approved for NSCLC, there are several other compounds currently in clinical development, including monoclonal antibodies to VEGF and inhibitors of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of the VEGF receptor, as described later in this review. Because of the issues of resistance and eligibility associated with currently approved targeted agents in NSCLC, there is a critical need for improved therapies. The subsequent sections of this review highlight important antiangiogenic targets as well as emerging clinical data regarding novel antiangiogenic compounds for NSCLC treatment.

Rationale for targeting angiogenic pathways in NSCLC

VEGF signaling

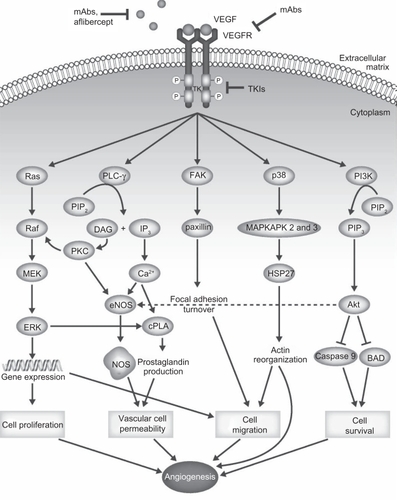

Important proangiogenic targets for the development of antiangiogenic therapies include VEGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), along with their corresponding receptors (VEGFR, FGFR, and PDGFR, respectively). The VEGF-related family of proangiogenic signaling factors comprises VEGF-A (commonly referred to as VEGF), VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGF-E, and placental growth factor (PlGF).Citation48 In addition to tumor angiogenesis, VEGF signaling mediates several other pathological conditions including inflammatory disorders, female reproductive processes, and intraocular neovascularization syndromes.Citation49 The VEGF ligands mediate their angiogenic effects via three receptor tyrosine kinases: VEGFR-1 (also known as fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 [flt-1]), VEGFR-2 (also known as kinase-insert domain receptor [KDR]), and VEGFR-3 (flt-4). The primary receptor for VEGF is VEGFR-2.Citation49 Binding of VEGF to its receptors causes receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation, and downstream signaling through a variety of pathways, including phosphoinositide (PI)-3 kinase (PI3K), v-src sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (Src), and phospholipase-Cγ (PLCγ), which can activate proliferation and migratory pathways driving angiogenesis ().Citation49 Neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2, members of the neuropilin family of receptors, are expressed on endothelial cells and may be activated by VEGF, dimerize with VEGFR-1 and -2, and activate downstream signaling;Citation50 inhibitors of neuropilin-VEGF interaction are undergoing preclinical evaluation for the treatment of cancer.Citation51,Citation52 In animal tumor models, VEGF is produced both by tumor cells and also by stromal tissue,Citation53,Citation54 although stromal expression of VEGF was not observed in a study of NSCLC samples from patients.Citation55 Upregulation of VEGF and VEGFR have been observed in NSCLC tumor samples, with expression correlated with tumor angiogenesis, shorter postoperative recurrence time, and shorter survival time.Citation55 A meta-analysis of NSCLC studies has also suggested that VEGF expression is an unfavorable prognostic factor for survival (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.27–1.72).Citation56

Figure 1 Connections between VEGF/VEGFR signaling and angiogenic processes. Depiction of the role of VEGFR signaling in tumor angiogenesis.

Adapted by permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd: Nat Rev Clin Oncol,Citation113 copyright 2009.

FGF signaling

The FGF family comprises 22 ligands that have a diverse array of biological functions. For example, FGF signaling plays a role in fetal development; mutations in FGFR1 are associated with bone disorders, and mutations in FGFR2 are known to cause various craniosynostosis syndromes (premature closure of sutures in the fetal skull before completion of brain growth).Citation57 FGF-1, FGF-2, FGF-4, FGF-5, and FGF-8 have been associated with angiogenesis.Citation58 Two FGF receptor tyrosine kinases, FGFR-1 and FGFR-2, are expressed in endothelial cells and can activate signaling pathways involved in tumor angiogenesis including the PI3K and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (ERK) pathways,Citation58 resulting in endothelial cell activation and recruitment of pericytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and monocytes.Citation58,Citation59 FGF also regulates expression of proteases, integrins, and cadherins involved in reorganization of the extracellular matrix.Citation60,Citation61 In this way, FGF signaling affects vascular integrity, an important component of the vascular remodeling required for angiogenesis.Citation62 In addition, cross-talk between FGFs, VEGFs, and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines may play a role in the modulation of blood vessel growth in various pathological conditions, including tumors.Citation58

PDGF signaling

PDGF ligands are released from platelets upon vascular damage.Citation63 There are five dimeric PDGF ligands, PDGF-AA, -BB, -CC, -DD, and -AB, and two receptor tyrosine kinases, PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β, which mediate downstream effects through some of the same pathways activated by VEGFR ().Citation64 These receptors are expressed on endothelial cells, pericytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells,Citation63 which aid in development of tumor microvessels. Release of PDGF-BB by endothelial cells recruits pericytes and vascular muscle cells, which, in turn, control vascular integrity, development, and stabilization.Citation65–Citation67 In a preclinical chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model involving chick eggs, PDGF-AA, -AB, and -BB induced development of new blood vessels, while in another model, PDGF-BB but not -AA stimulated the migration of rat brain capillary endothelial cells.Citation68,Citation69 Enhanced PDGF signaling has been associated with tumorigenesis and angiogenesis, as well as other pathological events such as atherosclerosis and re-stenosis of vessels after balloon angiography and coronary artery bypass grafting.Citation70 In addition, PDGF inhibition may be a rational strategy for treatment of fibrotic liver disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and the development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy.Citation70

The rationale for targeting the above signaling pathways arose from preclinical models, in which inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR, FGF/FGFR, or PDGF/PDGFR signaling resulted in reduced angiogenesis and impaired tumor proliferation. For example, treatment with a VEGF monoclonal antibody inhibited the growth of tumor cell lines that had been injected into nude mice, but did not affect the growth rate of the same cell lines in vitro, supporting the explanation that treatment was acting against angiogenesis rather than directly against tumor cells.Citation71,Citation72 Furthermore, activation of PDGF and FGF pathways has been implicated in the development of resistance to VEGF inhibition. In a mouse model of pancreatic cancer, relapse after treatment with an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody was associated with tumor revascularization secondary to hypoxia-mediated induction of other proangiogenic factors, including increased FGF-2 expression.Citation73 Upon combination treatment with both VEGF and FGF inhibitors, tumor revascularization and growth were reduced.Citation73 Likewise, expression of PDGFR has also been associated with resistance to VEGF-targeted therapy in the mouse pancreatic cancer model, with combined targeting of VEGF and PDGF signaling producing regression of established tumor blood vessels and inhibiting tumor growth.Citation74,Citation75 In fact, the VEGF, PDGF, and FGF signaling pathways appear to be highly integrated, suggesting that compensation and/or synergism between pathways occurs in angiogenesis.Citation76,Citation77 Thus, targeting multiple receptor tyrosine kinases may be required for effective antiangiogenic therapies.

In the clinical development of antiangiogenic therapies, two approaches have been used (); the first has been to inhibit ligand binding and receptor activation using targeted antibodies, while the second has been to inhibit receptor activation using tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting VEGFR, FGFR, and/or PDGFR. Results of Phase II and Phase III clinical trials of agents discussed in this review in NSCLC are summarized in .

Table 2 Approved and emerging antiangiogenic therapies for NSCLC

Table 3 Results from Phase II and III trials of VEGF, FGF, and PDGF inhibitors in NSCLC

Investigational antiangiogenic agents for NSCLC

Investigational therapeutic antibodies

Ramucirumab (IMC-1121B; ImClone Systems Inc, New York, NY) is a human monoclonal anti-VEGFR-2 antibody. In a Phase I study in which 37 patients with advanced solid malignancies were given escalating doses of ramucirumab, four patients (15%) had a partial response, and 11 patients (30%) exhibited a response or stable disease lasting 6 months or longer.Citation78 The most common serious adverse events included hypertension (13.5%), abdominal pain (10.8%), anorexia, vomiting, alkaline phosphatase increases, headache, proteinuria, dyspnea, and deep vein thrombosis (each in 5.4% of patients). A dosage of 13 mg/kg was considered the maximum-tolerated dose in this study, as two patients given the higher dose of 16 mg/kg experienced dose-limiting hypertension and deep venous thrombosis, respectively. Although none of the patients in this Phase I study had NSCLC, the findings provided the rationale for Phase II investigation of ramucirumab in this condition. A Phase II study is currently examining ramucirumab combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin as a first-line treatment for patients with NSCLC, including those with squamous histology or brain metastases, with a planned enrollment of approximately 40 patients.Citation79 Preliminary results from 15 patients demonstrated an ORR of 67% (10 patients) with one complete response and a median PFS of 6 months. Two patients experienced serious adverse events (grade 2 pneumothorax and grade 4 febrile neutropenia), and one additional patient withdrew from the study due to pneumothorax.Citation79

Investigational receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Given the multitude of intracellular signaling pathways that influence tumorigenesis, a number of potential advantages may exist with agents that inhibit multiple targets simultaneously. For example, this approach may prevent the development of resistance to antitumor agents. In addition, using a multitargeted approach, multiple tumorigenic pathways (such as angiogenesis and cell survival) may be inhibited and so maximize antitumor activity.

BIBF 1120 (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) is an orally available multitargeted TKI that inhibits signaling through VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, PDGFR-α/β, and FGFR-1, -2, and -3 as well as Src and flt-3.Citation80,Citation81 In preclinical models, including human tumor xenografts in nude mice and rat tumor models, BIBF 1120 reduced tumor vessel density and integrity, resulting in inhibition of tumor growth.Citation80 In Phase I studies, the most common drug-related adverse events observed with BIBF 1120 were reversible serum liver enzyme elevations and mild fatigue.Citation82–Citation84 When BIBF 1120 was combined with pemetrexed, a folate antimetabolite,Citation18 stable disease was achieved in 13 out of 26 patients (50%) with recurrent advanced NSCLC who had previously received one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen.Citation84 In this study, grade 3 fatigue was reported by six patients (23%), and grade 3 increases in alanine transaminase (ALT) were observed in three patients (11%). In Phase I studies of BIBF 1120 monotherapy in patients with advanced solid tumors, the first study (N = 61) observed grade 3 liver enzyme elevations in three patients receiving once-daily dosing with BIBF 1120 and no patients receiving twice daily dosing,Citation82 while the second study (N = 21) showed grade 3 elevations of ALT and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) in six patients each and grade 3 elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in three patients.Citation83

A Phase II trial tested BIBF 1120 monotherapy in 73 patients with relapsed NSCLC for which one or two lines of chemotherapy had previously failed and who had an ECOG performance status of 0–2.Citation85 Patients were assigned one of two doses: 150 mg (n = 37) or 250 mg (n = 36) twice daily. For all patients, median OS was 21.9 weeks, and median PFS was 6.9 weeks; one patient exhibited a partial response, and 48% of patients exhibited stable disease. Patients with an ECOG performance status of 0–1 (n = 56) exhibited a median PFS of 11.6 weeks and a median OS of 37.7 weeks. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities included ALT elevations (9.6%), diarrhea (8.2%), nausea (6.8%), γ-GT elevations (4.1%), abdominal pain (2.7%), vomiting (2.7%), anorexia (1.4%), AST elevations (1.4%), and fatigue (1.4%). Phase III trials are currently testing BIBF 1120 in combination with docetaxel in the LUME-Lung 1 study (NCT00805194) and pemetrexed in the LUME-Lung 2 study (NCT00806819). Of note, the LUME-Lung 2 study only includes patients with NSCLC of nonsquamous histology to conform with the FDA-approved indication of pemetrexed.Citation86

Other small molecule multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors are currently in clinical development. Sorafenib (Bay 43-9006; Nexavar®, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) targets tumor cell growth and angiogenesis by inhibiting signaling through VEGFR-2 and -3, PDGFR-β, v-raf 1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1(Raf), flt-3, and stem cell factor receptor (c-kit).Citation87 In a Phase II study of single-agent sorafenib in 51 patients with relapsed or refractory advanced nonsquamous NSCLC, there were no responses, but 30 patients (59%) exhibited stable disease.Citation88 Median PFS was 2.7 months, while median OS was 6.7 months. The most common grade 3 and 4 adverse events included hypertension in two patients (4%) and hand-foot skin disease in five patients (10%). In a larger Phase II study involving 342 patients with pretreated NSCLC and no evidence of brain metastases, patients were treated with sorafenib for two cycles; patients who responded continued on sorafenib for the second stage of the study, patients with stable disease were randomized to sorafenib or placebo, and those with progression discontinued. Preliminary results from the 97 patients randomized in stage 2 of the study show that sorafenib treatment prolonged PFS to 3.6 months compared with 1.9 months with placebo (P = 0.01) and resulted in stable disease for 16 patients (29%) compared with two patients with placebo (5%; P = 0.002).Citation89 The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were rash or hand-foot syndrome (15%) and fatigue (11%). Two patients receiving sorafenib in the first stage of the study and one patient in the second stage experienced grade ≥3 hemoptysis.

The Phase III ESCAPE trial evaluated sorafenib in combination with carboplatin plus paclitaxel in 926 patients with advanced untreated nonsquamous or squamous NSCLC,Citation90 but the study was halted when an interim analysis showed median OS was 10.7 months with sorafenib plus chemotherapy and 10.6 months with chemotherapy alone (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.94–1.41; P = 0.915). Likewise, there was no significant difference between treatments in PFS (4.6 versus 5.4 months, respectively; HR, 0.99, 95% CI, 0.84–1.16; P = 0.433) or ORR (27.4% versus 24.0%; P = 0.1015). Among patients with squamous histology, those receiving sorafenib (n = 109) had a lower OS (8.9 versus 13.7 months; HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.22–2.81) and PFS (4.3 versus 5.8 months; HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.94–1.83) compared with patients receiving chemotherapy alone (n = 114), whereas patients with other nonsquamous histologies had similar OS and PFS in the two treatment groups. The most common sorafenib-related grade ≥3 adverse events in all patients included rash (8%), hand-foot skin reaction (8%), and diarrhea (4%). The histological subtype of NSCLC did not appear to affect the overall tolerability of treatment; patients receiving sorafenib plus chemotherapy with nonsquamous versus squamous histologies had similar rates of drug-related adverse events occurring at all grades (77% versus 87%), grade 3 (26% versus 33%), and grade 4 (9% versus 9%), respectively. However, four out of six fatal hemorrhagic or bleeding events observed in this study (four with sorafenib and two with chemotherapy alone) occurred in patients with squamous histology (two in each arm).Citation90 The results of the ESCAPE study led to the exclusion of patients with squamous histology from the subsequent NExUS trial, which aimed to compare first-line treatment with sorafenib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone in a planned 900 patients with advanced NSCLC (NCT00449033). However, the NExUS trial was also halted because it did not meet the primary endpoint for improving OS.Citation91

Sunitinib (SU11248; Sutent®, Pfizer; New London, CT) targets signaling through VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, PDGFR-α/β, rearranged during transfection (RET), as well as c-kit and flt-3.Citation92 Sunitinib single-agent therapy was investigated in a Phase II trial of 63 patients with advanced NSCLC that had progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy.Citation93 Patients were excluded from this study if they had experienced a grade 3 hemorrhage or hemoptysis within 4 weeks before the start of the treatment; additionally, patients who had received prior antiangiogenic therapy were excluded. Seven patients achieved a partial response with sunitinib, resulting in an ORR of 11.1% (95% CI, 4.6–21.6), while 18 patients (28.6%) exhibited stable disease for ≥8 weeks. Median PFS was 12 weeks (95% CI, 10.0–16.1), median OS was 23.4 weeks (95% CI, 17.0–28.3), and the 1-year survival rate was 20.2% (95% CI, 10.0%–30.4%). The most common grade ≥3 adverse events were fatigue or asthenia in 18 patients (29%), lymphopenia in 15 patients (25%), pain or myalgia in 11 patients (14%), and dyspnea in seven patients (11%). Another second-line Phase II study of 47 patients with advanced NSCLC that had been treated with at least two chemotherapy regimens reported a partial response in one patient, giving an ORR of 2.1% (95% CI, 0.1–11.3), with 11 patients (23.4%) exhibiting stable disease for ≥8 weeks.Citation94 Median PFS and OS were 11.9 weeks (95% CI, 8.6–14.1) and 37.1 weeks (95% CI, 31.1–69.7), respectively, while the 1-year survival rate was 38.4% (95% CI, 24.2–52.5). Common grade ≥3 adverse events were fatigue or asthenia in eight patients (17%), neutropenia in four patients (9%), hypertension in four patients (9%), and dyspnea in three patients (6.4%). Sunitinib is currently being examined in a Phase II trial (CALGB 30704) as a second-line therapy in combination with pemetrexed (NCT00698815) and in a Phase III placebo-controlled trial (CALGB 30607) as a maintenance therapy after platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC (NCT00693992).

Cediranib (AZD2171; Recentin™, AstraZeneca; Wilmington, DE) inhibits signaling through VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, PDGFR-α/β, FGFR-1, and also has activity against c-kit.Citation95,Citation96 Cediranib was tested as a first-line therapy in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in a randomized, double-blind Phase II/III trial (BR24) in 296 patients with advanced NSCLC.Citation97 Patients with uncontrolled cardiovascular disease, severe hypertension, or hemoptysis within 4 weeks before treatment were excluded from this study. Despite initial results from the Phase II interim analysis suggesting higher ORR with cediranib (38%) than with placebo (16%, P < 0.0001), the study was halted to review imbalances in assigned causes of death due to toxicity of the 30-mg dose. Median PFS was not significantly improved with cediranib (5.6 months) over chemotherapy alone (5 months; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.56–1.08; P = 0.13), and a survival analysis update 10 months after study unblinding showed no significant advantage for cediranib over chemotherapy alone (10.5 versus 10.1 months; HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.57–1.06; P = 0.11). The most common grade ≥3 adverse events with cediranib included neutropenia (49%), fatigue (29%), increased thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (27%), hypertension (19%), diarrhea (15%), and dyspnea (10%). A similar trial (BR29) is ongoing using a lower cediranib dose (20 mg) in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel (NCT00795340). Another ongoing Phase II trial is currently evaluating cediranib in combination with pemetrexed in previously treated patients with NSCLC of all histological subtypes, with preliminary results from the first 33 enrolled patients showing an ORR of 16% (90% CI, 0.08–0.30) and grade ≥3 adverse events including neutropenia and fatigue, each of which was reported for seven patients.Citation98

ABT-869 (Abbott; Abbott Park, IL) inhibits signaling through VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, and PDGFR-β,Citation99,Citation100 and is being tested in an open-label randomized Phase II trial of NSCLC patients with disease progression after previous treatment.Citation101 An initial report on 24 patients receiving a 0.10 mg/kg daily dose and 24 patients receiving a 0.25 mg/kg daily dose showed 33% of all patients exhibited PFS of 16 weeks or longer. Median PFS was 109 and 108 days in the high- and low-dose groups, respectively. The most common grade ≥3 adverse events were hypertension (23% in the high-dose group), hand-foot syndrome (8% in the high-dose group), and fatigue (7% and 8% in the high- and low-dose groups, respectively).Citation101

Motesanib (AMG 706; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) inhibits signaling through VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, PDGFR-β, c-kit, and RET, and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis in tumor cell xenograft models.Citation102 Motesanib is currently undergoing evaluation in patients with NSCLC in combination with chemotherapy.Citation103,Citation104 In an initial Phase Ib study involving 26 patients with solid tumors, grade ≥3 deep vein thrombosis and neutropenia were reported in one patient each, one patient had a partial response, and seven patients achieved stable disease at 52 days (although none showed stable disease for longer than 24 weeks).Citation104 In a subsequent Phase II study, 181 patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC received treatment with motesanib 125 mg once daily or 75 mg twice daily or bevacizumab 15 mg/kg in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel.Citation103 Preliminary results showed partial responses in 23% and 22% of patients in the 125 mg and 75 mg motesanib groups, respectively, and 29% in the bevacizumab group, while median PFS was 7.4 months (95% CI, 5.3–8.5), 5.2 months (95% CI, 4.2–6.8), and 6.8 months (95% CI, 4.4–8.8) in the three treatment groups, respectively. The most common grade ≥3 adverse events in the three groups were diarrhea (19%, 13%, and 3%), dehydration (17%, 8%, and 3%), fatigue (17%, 5%, and 8%), anorexia (12%, 2%, and 3%), and nausea (10%, 3%, and 2%). The ongoing Phase III MONET1 study (NCT00460317) was initially suspended because of a higher incidence of mortality and hemoptysis in patients with squamous NSCLC treated with motesanib plus carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with those who had nonsquamous NSCLC. The trial has since resumed with an expected enrollment of 1400 patients, but recruitment is now limited to patients who have tumors with nonsquamous histology.Citation105

Pazopanib (GW786034; GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) inhibits VEGFR-1, -2, and -3, FGFR-1, PDGFR-α/β signaling, and c-kit.Citation106,Citation107 Pazopanib as preoperative monotherapy was investigated in a Phase II trial involving 35 patients with NSCLC scheduled for resection.Citation108 Patients with a history of hemoptysis or evidence of bleeding were excluded from the study. Of 35 patients, three had a partial response and 30 patients (86%) showed tumor-volume reduction (two of whom had a volume reduction of 50% or more). The most common grade ≥3 adverse event was an increase in serum ALT levels, reported for two patients.

Axitinib (AG-013736; Pfizer, New London, CT) targets VEGFR-1, -2, -3, and PDGFR-β.Citation109 Axitinib was evaluated in an open-label, single-arm Phase II study of 32 patients with NSCLC after at least one prior regimen of chemotherapy.Citation110 Patients were excluded from this study if they had a history of grade ≥2 hemoptysis or brain metastases. Three patients demonstrated a partial response, giving an ORR of 9%, while 10 patients (31%) experienced stable disease for 16 weeks or longer. Median PFS was 4.9 months (95% CI, 3.6–7.0 months), and median OS was 14.8 months (95% CI, 10.7–not estimable). Common grade ≥3 adverse events included fatigue in seven patients (22%), hypertension in three patients (9%), and hyponatremia in three patients (9%). Phase II clinical trials are currently evaluating first-line axitinib in combination with cisplatin and pemetrexed for patients with nonsquamous advanced NSCLC (NCT00768755) or in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced squamous NSCLC (NCT00735904).

Aflibercept (VEGF Trap; Regeneron, Tarrytown, NY), a fusion protein made up of portions of VEGFRs and human immunoglobulin G, has also shown activity in a Phase I clinical trial of patients with advanced solid tumors.Citation111 In a Phase II trial of patients with platinum-resistant, erlotinib-resistant adenocarcinoma of the lung, aflibercept was associated with an RR of 2%, median PFS of 2.7 months, and median OS of 6.2 months among 89 evaluable patients; the most common grade ≥3 adverse events included hypertension (23%), dyspnea (21%), and proteinuria (10%).Citation112 A Phase III trial is ongoing to evaluate aflibercept as second-line therapy in combination with docetaxel in patients with metastatic NSCLC (NCT00532155).

Conclusion

Challenges associated with currently approved targeted therapies in NSCLC include the development of resistance and patient eligibility, and so there is a need for more effective therapies that improve clinical benefit with minimal toxicity. Ongoing studies are evaluating new antiangiogenic treatments, with potentially promising antitumor activity suggested in Phase II studies of agents that target multiple angiogenic pathways (eg, VEGFR, PDGFR, and FGF pathways). However, while Phase III combination trials with monoclonal antibodies such as bevacizumab have been promising, recently completed combination trials with TKIs have been disappointing. Nonetheless, results from ongoing studies are eagerly awaited to help determine how these new antiangiogenic agents may be best used either alone or in combination with traditional chemotherapy regimens to improve outcomes in individual patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc (BIPI). Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Robert Lee, PhD, of MedErgy, which was contracted by BIPI for these services. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved at all stages of manuscript development.

Dr Chachoua has served on the Speakers Bureau for Eli Lilly, Genentech, and Response Genetics, Inc. Dr Ballas has received past honoraria from Eli Lilly.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Cancer SocietyCancer Facts and Figures, 2010Atlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society2010

- JemalASiegelRXuJWardECancer statistics, 2010CA Cancer J Clin20106027730020610543

- National Comprehensive Cancer NetworkNCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. V.2.2010. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2010.

- BreathnachOSFreidlinBConleyBTwenty-two years of Phase III trials for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: sobering resultsJ Clin Oncol20011961734174211251004

- CarneyDNLung cancer – time to move on from chemotherapyN Engl J Med2002346212612811784881

- ParkJOKimSWAhnJSPhase III trial of two versus four additional cycles in patients who are nonprogressive after two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in non small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200725335233523918024869

- SmithIEO’BrienMETalbotDCDuration of chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized trial of three versus six courses of mitomycin, vinblastine, and cisplatinJ Clin Oncol20011951336134311230476

- von PlessenCBergmanBAndresenOPalliative chemotherapy beyond three courses conveys no survival or consistent quality-of-life benefits in advanced non-small-cell lung cancerBr J Cancer200695896697317047644

- Tarceva® (erlotinib tablets) [package insert]South San Franscisco, CA Genentech, Inc.

- Iressa® (gefitinib tablets) [package insert]Wilmington, DEAstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP

- Avastin® (bevacizumab) [package insert]South San Francisco, CAGenentech, Inc.2009

- SharmaSVBellDWSettlemanJHaberDAEpidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancerNat Rev Cancer20077316918117318210

- CohenMHWilliamsGASridharaRChenGPazdurRFDA drug approval summary: gefitinib (ZD1839) (Iressa) tabletsOncologist20038430330612897327

- FukuokaMYanoSGiacconeGMulti-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected]J Clin Oncol200321122237224612748244

- ThatcherNChangAParikhPGefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer)Lancet200536694961527153716257339

- GiacconeGHerbstRSManegoldCGefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 1J Clin Oncol200422577778414990632

- HerbstRSGiacconeGSchillerJHGefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 2J Clin Oncol200422578579414990633

- GautschiOMackPCDaviesAMJablonsDMRosellRGandaraDRPharmacogenomic approaches to individualizing chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: current status and new directionsClin Lung Cancer20089Suppl 3S129S13819419927

- KimESHirshVMokTGefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised Phase III trialLancet200837296521809181819027483

- MaruyamaRNishiwakiYTamuraTPhase III study, V-15-32, of gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200826264244425218779611

- AstraZeneca. IRESSA (Gefitinib) receives marketing authorisation for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer in Europe http://www.astrazeneca.com/Media/Press-releases/Article/20090701-IRESSA-Gefitinib-Receives-Marketing-Authorisation-f. Accessed April 8, 2010.

- Erlotinib (Tarceva) for advanced non-small cell lung cancerMed Lett Drugs Ther20054712052526

- ShepherdFARodriguesPJCiuleanuTErlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2005353212313216014882

- Genentech IncFDA approves Tarceva as a maintenance therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer http://www.gene.com/gene/news/press-releases/display.do?method=detail&id=12727. Accessed April 21, 2010.

- CappuzzoFCiuleanuTStelmakhLErlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 studyLancet Oncol201011652152920493771

- JackmanDMYeapBYSequistLVExon 19 deletion mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with prolonged survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinibClin Cancer Res200612133908391416818686

- MitsudomiTKosakaTEndohHMutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene predict prolonged survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrenceJ Clin Oncol200523112513252015738541

- RielyGJPaoWPhamDClinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinibClin Cancer Res2006123 Pt 183984416467097

- EngelmanJAJannePAMechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancerClin Cancer Res200814102895289918483355

- KerbelRSAntiangiogenic therapy: a universal chemosensitization strategy for cancer?Science200631257771171117516728631

- CarmelietPAngiogenesis in life, disease and medicineNature2005438707093293616355210

- KreuterMKropffMFischaleckAPrognostic relevance of angiogenesis in stage III NSCLC receiving multimodality treatmentEur Respir J20093361383138819213790

- MeertAPPaesmansMMartinBThe role of microvessel density on the survival of patients with lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysisBr J Cancer200287769470112232748

- WeidnerNIntratumor microvessel density as a prognostic factor in cancerAm J Pathol199514719197541613

- Avastin® (Bevacizumab) for intravenous use [package insert]South San Francisco, CAGenentech, Inc.2008

- JohnsonDHFehrenbacherLNovotnyWFRandomized Phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200422112184219115169807

- HapaniSSherAChuDWuSIncreased risk of serious hemorrhage with bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysisOncology2010791–2273821051914

- SandlerAGrayRPerryMCPaclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2006355242542255017167137

- ReckMvon PawelJZatloukalPPhase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAiLJ Clin Oncol20092781227123419188680

- ReckMvon PawelJZatloukalPOverall survival with cisplatin-gemcitabine and bevacizumab or placebo as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised phase III trial (AVAiL)Ann Oncol20102191804180920150572

- KabbinavarFFMillerVAJohnsonBEO’ConnorPGSohCTlasIOverall survival (OS) in ATLAS, a phase IIIb trial comparing bevacizumab (B) therapy with or without erlotinib (E) after completion of chemotherapy (chemo) with B for first-line treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)J Clin Oncol.20102815s Abstract 7526.

- PolikoffJHainsworthJDFehrenbacherLSafety of bevacizumab (Bv) therapy in combination with chemotherapy in subjects with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated on ATLASJ Clin Oncol.20082615s Abstract 8079.

- HainsworthJDFangLHuangJEBRIDGE: an open-label phase II trial evaluating the safety of bevacizumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with advanced, previously untreated, squamous non-small cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol20116110911421107290

- ArdizzoniABoniLTiseoMCisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysisJ Natl Cancer Inst2007991184785717551145

- PatelJDHensingTARademakerAPhase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin plus bevacizumab with maintenance pemetrexed and bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200927203284328919433684

- PatelJDBonomiPSocinskiMATreatment rationale and study design for the pointbreak study: a randomized, open-label Phase III study of pemetrexed/carboplatin/bevacizumab followed by maintenance pemetrexed/bevacizumab versus paclitaxel/carboplatin/bevacizumab followed by maintenance bevacizumab in patients with stage IIIB or IV nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancerClin Lung Cancer200910425225619632943

- AdjeiAAMandrekarSJDyGKPhase II trial of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab for second-line therapy of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCCTG and SWOG study N0426J Clin Oncol201028461461919841321

- HicklinDJEllisLMRole of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesisJ Clin Oncol20052351011102715585754

- FerraraNGerberHPLeCouterJThe biology of VEGF and its receptorsNat Med20039666967612778165

- NeufeldGKesslerOThe semaphorins: versatile regulators of tumour progression and tumour angiogenesisNat Rev Cancer20088863264518580951

- JarvisAAllerstonCKJiaHSmall molecule inhibitors of the neuropilin-1 vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) interactionJ Med Chem20105352215222620151671

- BagriATessier-LavigneMWattsRJNeuropilins in tumor biologyClin Cancer Res20091561860186419240167

- FukumuraDXavierRSugiuraTTumor induction of VEGF promoter activity in stromal cellsCell19989467157259753319

- GerberHPKowalskiJShermanDEberhardDAFerraraNComplete inhibition of rhabdomyosarcoma xenograft growth and neovascularization requires blockade of both tumor and host vascular endothelial growth factorCancer Res200060226253625811103779

- YuanAYuC-JKuoS-HVascular endothelial growth factor 189 mRNA isoform expression specifically correlates with tumor angiogenesis, patient survival, and postoperative relapse in non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200119243244111208836

- DelmottePMartinBPaesmansMVEGF and survival of patients with lung cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis [in French]Rev Mal Respir2002195 Pt 157758412473944

- BeenkenAMohammadiMThe FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapyNat Rev Drug Discov20098323525319247306

- PrestaMDell’EraPMitolaSMoroniERoncaRRusnatiMFibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor system in angiogenesisCytokine Growth Factor Rev200516215917815863032

- MurakamiMZhengYHirashimaMVEGFR1 tyrosine kinase signaling promotes lymphangiogenesis as well as angiogenesis indirectly via macrophage recruitmentArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol200828465866418174461

- KleinSGiancottiFGPrestaMAlbeldaSMBuckCARifkinDBBasic fibroblast growth factor modulates integrin expression in microvascular endothelial cellsMol Biol Cell19934109739828298194

- UnderwoodPABeanPAGambleJRRate of endothelial expansion is controlled by cell:cell adhesionInt J Biochem Cell Biol2002341556911733185

- RusnatiMPrestaMFibroblast growth factors/fibroblast growth factor receptors as targets for the development of anti-angiogenesis strategiesCurr Pharm Des200713202025204417627537

- BeitzJGKimISCalabresiPFrackeltonARJrHuman microvascular endothelial cells express receptors for platelet-derived growth factorProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1991885202120251848018

- WuEPalmerNTianZComprehensive dissection of PDGF-PDGFR signaling pathways in PDGFR genetically defined cellsPLoS One2008311e379419030102

- LindahlPJohanssonBRLeveenPBetsholtzCPericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient miceScience199727753232422459211853

- AbramssonALindblomPBetsholtzCEndothelial and nonendothelial sources of PDGF-B regulate pericyte recruitment and influence vascular pattern formation in tumorsJ Clin Invest200311281142115114561699

- HellstromMKalenMLindahlPAbramssonABetsholtzCRole of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouseDevelopment1999126143047305510375497

- OikawaTOnozawaCSakaguchiMMoritaIMurotaSThree isoforms of platelet-derived growth factors all have the capability to induce angiogenesis in vivoBiol Pharm Bull19941712168616887537574

- RisauWDrexlerHMironovVPlatelet-derived growth factor is angiogenic in vivoGrowth Factors1992742612661284870

- LevitzkiAPDGF receptor kinase inhibitors for the treatment of PDGF driven diseasesCytokine Growth Factor Rev200415422923515207814

- KimKJLiBWinerJInhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivoNature199336264238418447683111

- FerraraNDavis-SmythTThe biology of vascular endothelial growth factorEndocr Rev19971814259034784

- CasanovasOHicklinDJBergersGHanahanDDrug resistance by evasion of antiangiogenic targeting of VEGF signaling in late-stage pancreatic islet tumorsCancer Cell20058429930916226705

- BergersGSongSMeyer-MorseNBergslandEHanahanDBenefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitorsJ Clin Invest200311191287129512727920

- ErberRThurnherAKatsenADCombined inhibition of VEGF and PDGF signaling enforces tumor vessel regression by interfering with pericyte-mediated endothelial cell survival mechanismsFASEB J200418233834014657001

- KanoMRMorishitaYIwataCVEGF-A and FGF-2 synergistically promote neoangiogenesis through enhancement of endogenous PDGF-B-PDGFRbeta signalingJ Cell Sci2005118Pt 163759376816105884

- NissenLJCaoRHedlundEMAngiogenic factors FGF2 and PDGF-BB synergistically promote murine tumor neovascularization and metastasisJ Clin Invest2007117102766277717909625

- SpratlinJLCohenRBEadensMPhase I pharmacologic and biologic study of ramucirumab (IMC-1121B), a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2J Clin Oncol201028578078720048182

- CamidgeDRBallasMSDubeySA phase II, open-label study of ramucirumab (IMC-1121B), an IgG1 fully human monoclonal antibody (MAb) targeting VEGFR-2, in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with stage IIIb/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)J Clin Oncol.20102815s Abstract 7588.

- HilbergFRothGJKrssakMBIBF 1120: triple angiokinase inhibitor with sustained receptor blockade and good antitumor efficacyCancer Res200868124774478218559524

- RothGJHeckelAColbatzkyFDesign, synthesis, and evaluation of indolinones as triple angiokinase inhibitors and the discovery of a highly specific 6-methoxycarbonyl-substituted indolinone (BIBF 1120)J Med Chem200952144466448019522465

- MrossKStefanicMGmehlingDPhase I study of the angiogenesis inhibitor BIBF 1120 in patients with advanced solid tumorsClin Cancer Res201016131131920028771

- OkamotoIKanedaHSatohTPhase I safety, pharmacokinetic, and biomarker study of BIBF 1120, an oral triple tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with advanced solid tumorsMol Cancer Ther20109102825283320688946

- EllisPMKaiserRZhaoYStopferPGyorffySHannaNPhase I open-label study of continuous treatment with BIBF 1120, a triple angiokinase inhibitor, and pemetrexed in pretreated non-small cell lung cancer patientsClin Cancer Res201016102881288920460487

- ReckMKaiserREschbachCA Phase II double-blind study to investigate efficacy and safety of two doses of the triple angiokinase inhibitor BIBF 1120 in patients with relapsed advanced non-small-cell lung cancerAnn Oncol. Epub 2011 Jan 6.

- Alimta® (pemetrexed disodium) [package insert]Indianapolis, INEli Lilly and Company122009

- WilhelmSMCarterCTangLBAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesisCancer Res200464197099710915466206

- BlumenscheinGRJrGatzemeierUFossellaFPhase II, multicenter, uncontrolled trial of single-agent sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory, advanced non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200927264274428019652055

- SchillerJHLeeJWHannaNHTraynorAMCarboneDPA randomized discontinuation Phase II study of sorafenib versus placebo in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have failed at least two prior chemotherapy regimens: E2501J Clin Oncol.20082615S Abstract 8014.

- ScagliottiGNovelloSvon PawelJPhase III study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol201028111835184220212250

- Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals IncOnyx Pharmaceuticals IncPhase 3 trial of nexavar in first-line advanced non-small cell lung cancer does not meet primary endpoint of overall survival Press release. June 14, 2010. Available from: http://www.onyx-pharm.com/view.cfm/685/Phase-3-Trial-of-Nexavar-in-First-Line-Advanced-Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer-Does-Not-Meet-Primary-Endpoint-of-Overall-Survival. Accessed July 27, 2010.

- SunLLiangCShirazianSDiscovery of 5-[5-fluoro-2-oxo-1,2- dihydroindol-(3Z)-ylidenemethyl]-2,4- dimethyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylic acid (2-diethylaminoethyl)amide, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial and platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinaseJ Med Chem20034671116111912646019

- SocinskiMANovelloSBrahmerJRMulticenter, Phase II trial of sunitinib in previously treated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200826465065618235126

- NovelloSScagliottiGVRosellRPhase II study of continuous daily sunitinib dosing in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancerBr J Cancer200910191543154819826424

- NikolinakosPHeymachJVThe tyrosine kinase inhibitor cediranib for non-small cell lung cancer and other thoracic malignanciesJ Thorac Oncol200836 Suppl 2S131S13418520296

- WedgeSRKendrewJHennequinLFAZD2171: a highly potent, orally bioavailable, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of cancerCancer Res200565104389440015899831

- GossGDArnoldAShepherdFARandomized, double-blind trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with either daily oral cediranib or placebo in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCIC Clinical Trials Group BR24 studyJ Clin Oncol2010281495519917841

- GadgeelSMWozniakAEdelmanMJCediranib, a VEGF receptor 1, 2, and 3 inhibitor, and pemetrexed in patients (pts) with recurrent non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)J Clin Oncol.20092715S Abstract e19007.

- AlbertDHTapangPMagocTJPreclinical activity of ABT-869, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitorMol Cancer Ther200654995100616648571

- ShankarDBLiJTapangPABT-869, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation and signaling in acute myeloid leukemiaBlood200710983400340817209055

- TanESalgiaRBesseBABT-869 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): interim resultsJ Clin Oncol.20092715S Abstract 8074.

- PolverinoACoxonAStarnesCAMG 706, an oral, multikinase inhibitor that selectively targets vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and kit receptors, potently inhibits angiogenesis and induces regression in tumor xenograftsCancer Res200666178715872116951187

- BlumenscheinGRKabbinavarFFMenonHRandomized, open-label phase II study of motesanib or bevacizumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin (P/C) for advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)J Clin Oncol20102815s7528

- PriceTJLiptonLMcGreivyJMcCoySSunYNRosenthalMASafety and pharmacokinetics of motesanib in combination with gemcitabine for the treatment of patients with solid tumoursBr J Cancer20089991387139418971935

- Amgen. Independent Data Monitoring Committee recommends resuming enrollment of non-squamous NSCLC patients in the motesanib MONET1 trial. http://www.amgen.com/media/media_pr_detail.jsp?year=2009&releaseID=1255738. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- SloanBScheinfeldNSPazopanib, a VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for cancer therapyCurr Opin Investig Drugs200891213241335

- KumarRKnickVBRudolphSKPharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation from mouse to human with pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor with potent antitumor and antiangiogenic activityMol Cancer Ther2007672012202117620431

- AltorkiNLaneMEBauerTPhase II proof-of-concept study of pazopanib monotherapy in treatment-naive patients with stage I/II resectable non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol201028193131313720516450

- RugoHSHerbstRSLiuGPhase I trial of the oral antiangiogenesis agent AG-013736 in patients with advanced solid tumors: pharmacokinetic and clinical resultsJ Clin Oncol200523245474548316027439

- SchillerJHLarsonTOuSHEfficacy and safety of axitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a Phase II studyJ Clin Oncol200927233836384119597027

- LockhartACRothenbergMLDupontJPhase I study of intravenous vascular endothelial growth factor trap, aflibercept, in patients with advanced solid tumorsJ Clin Oncol201028220721419949018

- LeighlNBRaezLEBesseBA multicenter, phase 2 study of vascular endothelial growth factor trap (Aflibercept) in platinum- and erlotinib-resistant adenocarcinoma of the lungJ Thorac Oncol2010571054105920593550

- IvySPWickJYKaufmanBMAn overview of small-molecule inhibitors of VEGFR signalingNat Rev Clin Oncol200961056957919736552

- LababedeOMezianeMRiceTSeventh edition of the cancer staging manual and stage grouping of lung cancer: quick reference chart and diagramsChest2011139118318921208878