Abstract

Purpose

To enhance prognostic information of protein biomarkers for clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCCs), we analyzed them within prognostic groups of ccRCC harboring different tumor characteristics of this clinically and molecularly heterogeneous tumor entity.

Methods

Tissue microarrays from 145 patients with primary ccRCC were immunohistochemically analyzed for VHL (von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor), Ki67 (marker of proliferation 1), p53 (tumor protein p53), p21 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A), survivin (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5), and UEA-1 (Ulex europaeus agglutinin I) to assess microvessel-density.

Results

When analyzing all patients, nuclear staining of Ki67 (hazard ratio [HR] 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.12) and nuclear survivin (nS; HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.08) were significantly associated with disease-specific survival (DSS). In the cohort of patients with advanced localized or metastasized ccRCC, high staining of Ki67, p53 and nS predicted shorter DSS (Ki67: HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.11; p53: HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09; nS: HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14). In organ-confined ccRCC, patients with high p21-staining had a longer DSS (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92–0.99). In a multivariate model with stepwise backward elimination, tumor size and p21-staining showed a significant association with DSS in patients with “organ-confined” ccRCCs. The p21-staining increased the concordance index of tumor size from 0.75 to 0.78. In patients with “organ-confined” ccRCC, no disease-related deaths occurred in the group with p21-expression below the threshold of 32.5% p21-positive cells (log rank test: P=0.002).

Conclusion

The prognostic information of the studied protein biomarkers depended on anatomic tumor stages, which displayed different acquired biological tumor characteristics. Analysis of prognostic factors within different clinical ccRCC groups could help to enhance their prognostic power. The p21-staining was an independent prognostic factor and increased prognostic accuracy in a predictive model in “organ-confined” ccRCC.

Introduction

Clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCCs) have a very heterogeneous course of disease. To date, clinical outcome is not reliably predictable with established clinical and pathological factors. Many attempts were made to enhance the prognostic power of established markers, such as nomograms based on clinical and pathological variables and the evaluation of molecular markers.Citation1 Nonetheless, TNM stage and Fuhrman grade still yield the highest prognostic power.Citation2,Citation3

Based on the TNM staging system, ccRCC can be classified into three major prognostic groups: “organ-confined” (pathological tumor stage, pT1-pT2; lymph node stage, N0; metastases stage, M0), “advanced localized” (pT3-pT4 N0 M0), and “metastasized” (any pT, N1, and/or M1) ccRCCCitation2 with 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) rates from 82% to 95%,Citation4 24% to 72%,Citation5 and 5% to 30%,Citation6 respectively. These groups display different acquired characteristics of cancers such as tissue invasion and metastasis. Organ-confined ccRCC is nearly always present without invasion of the surrounding renal tissue.Citation7 This is reflected in the low rate of distant metastasis between 4.2% and 7.1% in ccRCC ≤4 cm at initial presentation.Citation8

Protein expression analysis of gene products with important functions in tumorigenesis and with altered expression in cancer initiation and/or progression, respectively, can help to identify prognostic groups more accurately.Citation3,Citation9

Weiss et al showed that the predictive capability of the molecular biomarker p21 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A) is dependent on ccRCC biology, with high nuclear p21-expression being associated with longer DSS in organ-confined and advanced localized disease, but shorter survival in metastasized disease.Citation10 High Ki67 (marker of proliferation 1)-expression, a measure of high proliferation activity, is a negative predictor of DSS in ccRCC patients.Citation3 High p53-staining is associated with TP53-mutations and with shorter survival in ccRCC.Citation1 p21 can arrest the cell cycle as an effector of p53, but also has p53-independent growth promotional, pro-apoptotic, and anti-apoptotic effects in ccRCC.Citation10 The inhibitor of apoptosis, survivin, is highly upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor outcome.Citation11,Citation12 VHL (von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor)-alterations are an initial step in the development of most ccRCC leading to angiogenesis, cell migration, and proliferation.Citation1 In addition, VHL is a regulator of p53 stabilization.Citation13 Angiogenesis was proven to be an important step in development and progression of ccRCC with microvessel density (MVD) as an easily assessable marker of tumor vascularization.Citation14

These molecular markers reflect the complex interplay between apoptosis, cell cycle regulation, growth signaling, angiogenesis, and immortalization in ccRCC. In this study, we analyzed whether the immunohistochemical staining profiles of Ki67, p53, p21, nuclear survivin (nS), cytoplasmic survivin (cS), VHL, and MVD have distinct associations with clinical outcome in the subgroups of organ-confined or advanced localized and metastasized ccRCC. The primary aim of the present study is to identify if these molecular markers add prognostic information to established clinical and pathological markers in biologically distinct subgroups of ccRCC.

Materials and methods

Tissue specimens

Tumor specimens from 145 patients suffering from primary ccRCC with available paraffin blocks and follow-up data were analyzed retrospectively. All patients underwent total or partial nephrectomy at the Department of Urology Dresden between 1993 and 2000. Follow-up of patients was retrieved from in-house medical records and/or from the attending urologist or general practitioner. For all patients, histological classification and tumor grade according to Fuhrman were reevaluated on the histopathological slides in a blinded fashion (by MM and TW). Tumor stage was reclassified according to the Union for International Cancer Control classification 2009.Citation15 Tissue collection and analysis was acknowledged by the internal review board of the Technical University of Dresden (EK59032007 and EK195092004). Patients gave written informed consent.

Tissue microarrays

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed including two representative tumor cores (one core from the center and one from the margin of the tumor) with a diameter of 0.6 mm from each patient. Selection of representative tissue areas was performed by a trained pathologist (MM) on large sections for each ccRCC. Normal kidney specimens were used as controls. Specimens of 12 metastases were incorporated in the TMA. Sections of 4 μm thickness were mounted on adhesive glass slides. Quality control with regard to type of tissue and grade was performed on hematoxylin and eosin stained TMA sections.

Immunohistochemistry

As previously described,Citation16 all sections were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval for p21, survivin, and VHL was achieved by heating the sections in 0.01 M citrate buffer pH 6.0 at 120°C for 10 minutes. After blocking endogenous peroxidase, and after incubation with the blocking serum (universal ABC-AP Kit; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: mouse monoclonal antihuman antibodies against p21 (clone 4D10; 1:80; Nova Castra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) and against VHL (clone immunoglobulin (Ig)32; 1:50; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) as well as rabbit polyclonal antihuman survivin antibody (clone AF886; 1:200; R & D Systems, Inc., Abingdon, UK). Detection was achieved by using an anti-mouse/anti-goat ABC-Kit and visualization was accomplished with new fuchsine. For Ki67, p53, and UEA-1 (Ulex europaeus agglutinine-1), antigen retrieval was performed at 95°C for 20 minutes using 0.01 M citrate buffer pH 6.0. Mouse monoclonal antihuman Ki67 (clone MIB-1; 1:300; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), p53 (clone DO-1; 1:100; Oncogene, Seattle, WA, USA), and UEA-1 (clone B-1065; 1:10; Vector Laboratories, Inc.) antibodies were used. After incubation with ABC-reagent (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit anti-mouse; Vector Laboratories, Inc.), DAB (3,3’-Diaminobenzidin) was used for visualization and Meyer’s Hemalaun for counterstaining. For every TMA-tissue core, the number of positively stained cells per 100 cells was evaluated manually by light microscopy at 400× magnification blinded to the clinical data (performed by TW). The mean of two tumor-cores per case was calculated. Nuclear staining was evaluated for p21, p53, Ki67, and survivin. Cytoplasmic staining was evaluated for VHL and also for survivin. MVD was analyzed by the method of Weidner et alCitation17 using the expression of UEA-1 in endothelial cells. Random samples of all stainings were reevaluated by a second person (MM); no interobserver difference in marker expression of more than 10% was noted. No marked heterogeneity of any staining was observed in parallel analyzed large sections in a subset of patients.

Statistical analysis

All protein markers were analyzed as continuous variables. Associations between protein markers and categorical clinicopathological variables were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. DSS was measured as time from nephrectomy to death of disease. Uni- and multivariate survival analyses were performed with Cox proportional hazards regression models. Assumption of proportional hazards was tested for every variable by Schoenfeld’s partial residuals. Multivariate models were performed with stepwise Wald backward exclusion using 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 as thresholds for exclusion. Hazard ratios (HRs) of the retaining variables were internally validated with bootstrapping analysis with 1,000 samples, and predictive accuracies of the final models were quantified by using the concordance index. For easier assessment of marker expression in clinical routine, p21 expression was classified into two categories: >32.5% (normal) and ≤32.5% (altered) cells with positive p21-staining as used by Weiss et al on renal cell carcinoma TMA sections.Citation10 Survival functions of categorized p21 staining were visualized with Kaplan–Meier plots, and differences between groups were assessed with log rank tests. Generally, P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Due to the explorative character of the study, we did not correct alpha-error due to multiple testing. Statistical analysis was accomplished with PASW 18.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R 2.15.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Twenty-eight of the 145 patients (19.3%) died of disease and 27 (18.6%) died of other causes. Mean and median follow-up time of the surviving patients was 9.2 (standard error 4.1) and 9.7 years (interquartile range [IQR] 8.8–10.5), respectively. Patient characteristics are given in .

Table 1 Clinicopathological patient characteristics

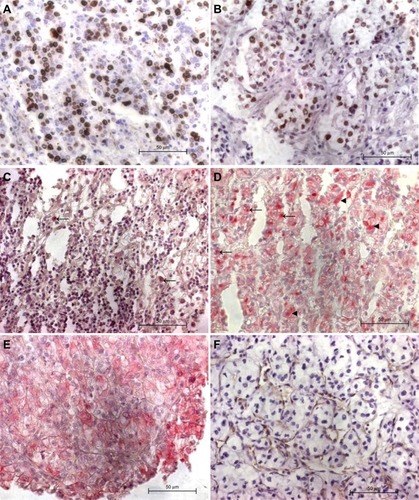

Immunohistochemistry was evaluable in all cases for Ki67, in 144 cases for p21 and UEA-1, in 143 cases for p53 and VHL, and in 141 cases for survivin. Representative stainings are shown in . The median percentage of positive-stained ccRCC cells for Ki67, p53, p21, cS, nS, and VHL were 5.5% (IQR 3–8.7), 15.5% (IQR 7–24.5), 26% (IQR 17–37.5), 34.5% (IQR 17–50.5), 6.5% (IQR 2.8–12.8), and 18% (IQR 4.5–28.5), respectively. Median vessel count according to Weidner et alCitation17 was 19.5 (IQR 7.8–33.9). High Fuhrman grade (grade 3–4) was significantly associated with higher median Ki67-staining, lymph node involvement with lower cS-staining, and MVD (Table S1). No other significant associations to clinicopathological parameters were observed.

Figure 1 Representative ccRCC cores with positive immunohistochemical stainings.

Abbreviations: ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinomas; MVD, microvessel density; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor; Ki67, marker of proliferation 1; p53, tumor protein p53; p21, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A; survivin, baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5.

In univariate Cox proportional hazards model analyses of the whole cohort, high pT stage, TNM stage, Fuhrman grade, larger tumor size, as well as positive N stage and M stage were predictors for a shorter DSS ().

Table 2 Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model analyses of clinicopathological and molecular variables for disease-specific survival in all analyzed ccRCC patients as well as in the subgroups of patients with organ-confined disease, with advanced disease (advanced-localized and metastasized combined) and the subgroup of advanced-localized disease

For all analyzed protein marker variables, assumption of linearity could be made and Cox proportional hazard models were constructed. Higher Ki67- and nS-staining were associated with an 8% and 4% increased risk of death caused by ccRCC for every 1% increase in stained cells, respectively (Ki67: HR 1.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.12, P<0.001; nS: HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.08, P=0.016). Patients with higher p53-staining or lower MVD tended to have a higher risk of death due to ccRCC (p53: HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.96–1.06, P=0.096; MVD: HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.95–1, P=0.071). The other biomarkers were not predictive for DSS ().

When analyzing the 36 patients with advanced localized or metastasized ccRCC (pT3-4 N0 M0 or any pT, N1, and/or M1, respectively) together, the presence of lymph node or distant metastasis were the strongest predictors for shorter DSS. Higher Fuhrman grade tended to be associated with DSS (). In these patients, Ki67-, p53-, and nS-stainings were significantly predictive for DSS (Ki67: HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.11, P=0.002; p53: HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.09, P=0.025; nS: HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02–1.14, P=0.006; ). These associations of Ki67-, p53-, and nS-stainings with DSS were also noticed in the 24 patients with advanced localized disease (Ki67: HR 1.08, 95% CI 1–1.16, P=0.047; p53: HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.16, P=0.009; nS: HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06–1.32, P=0.004; ). We did not perform Cox proportional hazards model analysis for the subgroup of the 12 patients with metastasized ccRCC due to the small number.

For the 109 patients with organ-confined ccRCC (pT1-2 N0 M0), larger tumor size as well as pT2 were associated with shorter DSS in univariate survival analyses (). Patients with higher p21-staining had a decreased risk of death due to ccRCC (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92–0.99, P=0.031). Hence, every 1% decrease of p21-staining increases risk of death due to ccRCC by 4%. No significant association to DSS was seen for the other biomarkers ().

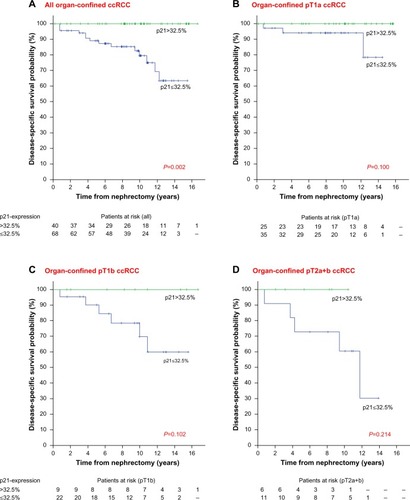

After classification of the p21-staining in patients with normal (>32.5%) and altered (≤32.5%) staining according to Weiss et al,Citation10 68 patients with organ-confined ccRCC (63%) had an altered p21-staining. These patients had a significantly increased risk of death due to ccRCC (log rank test: P=0.002; ). This effect could be observed in patients with pT1a, pT1b, and pT2 tumors (log rank test for trend: P=0.009; ). Cox regression analysis could not be performed as no ccRCC-specific deaths occurred in the subgroup of patients with altered p21-staining.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier plots for dichotomized p21-staining (>32.5% versus ≤32.5%).

Abbreviations: ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinomas; pT, pathological tumor stage; p21, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A.

These results indicate a differential prognostic impact of immunohistochemical staining signatures in organ-confined, advanced localized, and metastasized ccRCC. Therefore, we performed multivariate analysis separately for organ-confined ccRCC. The multivariate model comprised Fuhrman grade (grade 1 versus grade 2), tumor size, pT stage (pT1 versus pT2), and continuous p21-staining. After stepwise backward deletion with different deletion thresholds, continuous p21-staining and tumor size remained in the model. Consecutively, bootstrapping analysis was performed for the remaining variables. Continuous p21-staining and tumor size were independent prognostic factors for DSS in the group of organ-confined ccRCC (p21: HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.92–0.99, P=0.027; tumor size: HR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.05, P=0.011). Compared to tumor size alone, inclusion of continuous p21-staining increased the concordance index from 0.75 to 0.78. However, this difference was not statistically significant. Due to the small numbers of patients with advanced localized or metastasized disease, we did not construct multivariate models for these cohorts.

Discussion

In the last decades, substantial achievements in predicting disease-specific mortality of patients with ccRCC were made (eg, by further improvement of the TNM-staging system or by introduction of algorithms and nomograms incorporating clinical and pathological data).Citation1,Citation2 These scores, such as the SSIGN (Mayo Clinic “stage, size, grade, and necrosis” score) or Leibovich score have already been externally validated.Citation18,Citation19 However, prediction of biology of ccRCC remains difficult and TNM-staging is currently the most relevant predictor of ccRCC.Citation20 With increased understanding of tumor biology, molecular biomarkers are becoming an attractive target for improvement of prognosis prediction.Citation6 Many studies analyzing the prognostic value of biomarkers were conducted, but results were sometimes conflicting, potentially reflecting the nonuniform molecular changes in ccRCC during its evolution.Citation21 For example, carbonic anhydrase IX is one of the most important predictors of survival in metastasized ccRCC but has no prognostic value in localized disease.Citation22 Taking this into account, we stratified our analyses of the prognostic biomarkers in organ-confined ccRCC (noninvasive) as well as advanced localized and metastasized (invasive) ccRCC as organ-confined ccRCC do not usually invade the surrounding kidney tissue,Citation7 which is a characteristic of more advanced tumors. In this study, immunohistochemical staining patterns of VHL, Ki67, p53, p21, nS, and cS as well as MVD were analyzed to investigate whether they displayed the heterogeneity of ccRCC.

The proliferation marker Ki67 is one of the best established prognostic biomarkers for disease-specific recurrence in non-metastasized and metastasized ccRCC.Citation3,Citation23,Citation24 In our patient cohort, high Ki67-staining was related to shorter DSS when analyzing all patients as well as the subgroup with advanced localized or metastasized ccRCC. In accordance with two studies analyzing Ki67-expression in pT1 renal cell carcinomas, we could not identify a relation to DSS in organ-confined ccRCC.Citation25,Citation26

The role of p53 in ccRCC is ambiguous.Citation1 Whole genome sequencing of ccRCC revealed that p53 mutations are not frequent in ccRCC.Citation21 However, high p53-expression is associated with poor survival.Citation3,Citation24,Citation27 In our cohort and the cohort of Kramer et al,Citation28 p53-staining only tended to be associated with DSS, when evaluating all patients. In our study, it was not associated with survival in the subgroup of organ-confined ccRCC. However, in patients with advanced localized and metastasized ccRCC, p53-staining was significantly linked to DSS in our cohort, regardless of whether studied separately or combined. This indicates that indirect p53-alterations might be a later step in ccRCC progression.

The cell cycle control, microtubule stabilization, and antiapoptotic functions of survivin seem to be associated with intracellular protein localization.Citation29 Similar to Parker et al,Citation11 we observed a significant relation between the expression of the nuclear survivin pool and prognosis when analyzing all patients. High nS-staining was associated with shorter DSS in patients with advanced localized and metastasized ccRCC or with locally advanced ccRCC only, but not in patients with organ-confined ccRCC. To our knowledge, no other study analyzed the value of nS-expression in organ-confined ccRCC. Parker et al,Citation11 also observed a cS-staining in ccRCC but did not pursue it further. In our analysis, the cS-staining was not a predictor of prognosis for ccRCC, in contrast to another study on 85 ccRCC patients.Citation12 One reason for the different results might be the antibodies used. We applied the commonly used polyclonal antibody AF886, whereas the monoclonal anti-survivin antibody used by Byun et alCitation12 might not detect all survivin splice variants.

Low MVD is strongly associated with advanced disease.Citation14 This might be a reason why MVD tended to be related with DSS in the whole cohort but lost its predictive ability when studied in the ccRCC subsets.

In a large cohort and in our study, VHL-staining was not associated with DSS.Citation9 Possibly, VHL loss-of-function mutations lead to decreased immunohistochemical staining, but patients with lack of VHL mutations and, thus, with high VHL-staining display a shorter DSS.Citation30,Citation31

Interestingly, in our study, high nuclear p21-staining was associated with longer DSS in organ-confined but not in advanced localized or metastasized ccRCC. This association was seen when analyzing p21-staining as a continuous variable. Most notably, no disease-related death occurred in patients with altered p21-staining when p21-staining results were categorized according to Weiss et al.Citation10 This groupCitation10 and Klatte et alCitation22 also observed an association between high p21-staining and favorable prognosis, but they included patients with organ-confined and advanced localized ccRCC. As both studies did not stratify the analysis of p21-staining for these two subgroups, it is unknown if this association would be more pronounced if the subgroup of organ-confined ccRCC was analyzed separately. In addition, p21-staining lost predictive ability when analyzed in patients with advanced localized ccRCC only.

In contrast to localized ccRCC, high nuclear p21-staining was associated with poor prognosis in metastasized disease in the study of Weiss et al.Citation10 Analyzing the 12 patients with metastases, we observed a trend for a shorter DSS in patients with high nuclear p21-staining (data not shown). Studies evaluating p21-staining in localized and metastasized ccRCC together could not uncover its prognostic value.Citation32,Citation33 Function of p21 depends on its subcellular localization. After phosphorylation, p21 is localized in the cytoplasm and possesses p53-independent, growth promotional, and anti-apoptotic functions.Citation10 In the study of Weiss et al, high cytoplasmic p21-staining was associated with shorter survival in metastasized ccRCC.Citation10 Future studies on larger patient cohorts should elucidate the prognostic potential of subcellular p21 localization.

In summary, these data suggest that p21 might play an ambiguous role in the biological behavior of ccRCC. Consistent with that, p21 is involved in various opposing processes. Depending on conditions, it can act as inhibitor or promoter of cell cycle progression.Citation34 Besides the antiapoptotic effects of the cytoplasmic phosphorylated form, it has many oncogenic transcriptional activities.Citation34 In breast cancer, p21 is a downstream target of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and is essential for tumor cell invasion.Citation35 Interestingly, TGF-β is regulated via VHL in ccRCC.Citation36,Citation37 p21 possibly acts as cell cycle regulator in organ-confined ccRCC, but its function switches during ccRCC progression to promote cell migration and invasion.

In our multivariate analyses, p21-staining was an independent predictor of DSS in organ-confined ccRCC and it enhanced the predictive ability of tumor size, whereas it was not an independent prognostic factor in the studies of Weiss et alCitation10 and Klatte et al.Citation22 Due to the low number of patients with advanced localized and metastasized disease, we only performed multivariate analyses for patients with organ-confined ccRCC.

Kim et alCitation3 first described that incorporation of the independent survival predictors p53, vimentin, and carbonic anhydrase IX in a system of clinical markers improved predictive ability in nonselected ccRCC from 0.75 to 0.79. To our knowledge, the present analysis is the first study evaluating prognostic ability of biomarkers in the subset of organ-confined ccRCC. However, due to the high predictive accuracy (up to 88%) of prognostic models based only on clinical and radiological parameters, to date, none of the prognostic models incorporating biomarkers are recommended for routine use.Citation1,Citation20

Our analysis is mainly limited by the retrospective design, a relatively limited number of cases, and the small number of patients with metastases. The multiple testing procedures could have led to significant associations by chance, even if we evaluated results not only by statistical but also clinically immanent association. Due to the explorative design of the study, we did not use procedures to reduce alpha-error besides bootstrapping analysis in the multivariate model. Therefore, independent external validation of these data is needed to support our findings. After testing for nonlinearity, we analyzed all biomarkers as continuous variables to avoid insignificant associations by arbitrarily chosen cutoff values.

The study is further limited by the lack of standards for staining technique, storage, and fixation of immunohistochemical procedures. We used normal renal tissue as negative control in our study. Recent studies using techniques such as exome gene sequencing revealed an underestimated heterogeneity by analyzing only a few parts of the tumor.Citation38 To address this, we analyzed two TMA cores per tumor. Immunohistochemical studies revealed that, even in tumors with higher intratumor heterogeneity than ccRCC, the evaluation of two TMA cores leads to accordance of staining results with whole section slides in 90%–95% of cases.Citation39 For all analyzed proteins, the percentage of positive-stained cells between tumor center and periphery correlated significantly (P<0.001, data not shown).

The evaluation of prognostic factors stratified to ccRCC subgroups helped to enhance their prognostic ability in the context of the varying tumor biology and the molecular evolution of this disease. Embedded in the literature, these data will help to improve the prediction of disease-specific mortality and disclose targets for targeted therapy. For a robust conclusion regarding the prognostic value of p21-staining in organ-confined ccRCC shown in the present study, it should be validated in larger independent cohorts.

Conclusion

The analyzed molecular markers had distinct associations with prognosis when stratified to clinical and tumor biological subgroups. High expression of Ki67, nS, and p53 were significantly associated with worse disease-specific mortality in localized advanced or metastasized ccRCC. In contrast, p21-staining was only associated with prognosis in organ-confined disease. p21-expression remained a significant survival predictor in multivariate analyses. Further analyses are needed to confirm this association.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Technische Universität Dresden.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Median staining frequencies of the analyzed immunohistochemical markers and MVD in primary ccRCC dependent on clinicopathological variables of the patients

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SunMShariatSFChengCPrognostic factors and predictive models in renal cell carcinoma: a contemporary reviewEur Urol201160464466121741163

- MochHArtibaniWDelahuntBReassessing the current UICC/AJCC TNM staging for renal cell carcinomaEur Urol200956463664319595500

- KimHLSeligsonDLiuXUsing protein expressions to predict survival in clear cell renal carcinomaClin Cancer Res200410165464547115328185

- FicarraVSchipsLGuillèFMultiinstitutional European validation of the 2002 TNM staging system in conventional and papillary localized renal cell carcinomaCancer2005104596897416007683

- FicarraVGalfanoAGuilleFA new staging system for locally advanced (pT3-4) renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter European study including 2,000 patientsJ Urol20071782418424 discussion 423–42417561128

- LaneBRKattanMWPredicting outcomes in renal cell carcinomaCurr Opin Urol200515528929716093851

- EbleJNSauterGEpsteinJISesterhennIAWorld Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital OrgansLyonIARC Press20047

- LughezzaniGJeldresCIsbarnHTumor size is a determinant of the rate of stage T1 renal cell cancer synchronous metastasisJ Urol200918241287129319683281

- DahindenCIngoldBWildPMining tissue microarray data to uncover combinations of biomarker expression patterns that improve intermediate staging and grading of clear cell renal cell cancerClin Cancer Res2010161889820028743

- WeissRHBorowskyADSeligsonDp21 is a prognostic marker for renal cell carcinoma: implications for novel therapeutic approachesJ Urol200717716368 discussion 68–6917162001

- ParkerASKosariFLohseCMHigh expression levels of survivin protein independently predict a poor outcome for patients who undergo surgery for clear cell renal cell carcinomaCancer20061071374516736510

- ByunSSYeoWGLeeSELeeEExpression of survivin in renal cell carcinomas: association with pathologic features and clinical outcomeUrology2007691343717270609

- RoeJSKimHLeeSMKimSTChoEJYounHDp53 stabilization and transactivation by a von Hippel-Lindau proteinMol Cell200622339540516678111

- SandlundJHedbergYBerghAGrankvistKLjungbergBRasmusonTEvaluation of CD31 (PECAM-1) expression using tissue microarray in patients with renal cell carcinomaTumour Biol200728315816417510564

- SobinLGospodarowiczMWittekindCTNM Classification of Malignant Tumours7th edNew YorkUICC International Union Against Cancer, Wiley-Blackwell2009

- WeberTMeinhardtMZastrowSWienkeAFuesselSWirthMPImmunohistochemical analysis of prognostic protein markers for primary localized clear cell renal cell carcinomaCancer Invest2013311515923327192

- WeidnerNSempleJPWelchWRFolkmanJTumor angiogenesis and metastasis – correlation in invasive breast carcinomaN Engl J Med19913241181701519

- PichlerMHuttererGCChromeckiTFExternal validation of the Leibovich prognosis score for nonmetastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma at a single European center applying routine pathologyJ Urol201118651773177721944989

- ZigeunerRHuttererGChromeckiTExternal validation of the Mayo Clinic stage, size, grade, and necrosis (SSIGN) score for clear-cell renal cell carcinoma in a single European centre applying routine pathologyEur Urol201057110210919062157

- LjungbergBBensalahKBexAGuidelines on Renal Cell CarcinomaEuropean Association of Urology2013 Available from: http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/10_Renal_Cell_Carcinoma_LRV2.pdfAccessed December 30, 2013

- AraiEKanaiYGenetic and epigenetic alterations during renal carcinogenesisInt J Clin Exp Pathol201041587321228928

- KlatteTSeligsonDBLaRochelleJMolecular signatures of localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma to predict disease-free survival after nephrectomyCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200918389490019240241

- BuiMHVisapaaHSeligsonDPrognostic value of carbonic anhydrase IX and KI67 as predictors of survival for renal clear cell carcinomaJ Urol20041716 Pt 12461246615126876

- KroezeSGBijenhofAMBoschJLJansJJDiagnostic and prognostic tissuemarkers in clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinomaCancer Biomark20107626126821694464

- ChevilleJCZinckeHLohseCMpT1 clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a study of the association between MIB-1 proliferative activity and pathologic features and cancer specific survivalCancer20029482180218412001115

- GelbABSudilovskyDWuCDWeissLMMedeirosLJAppraisal of intratumoral microvessel density, MIB-1 score, DNA content, and p53 protein expression as prognostic indicators in patients with locally confined renal cell carcinomaCancer1997809176817759351546

- PhuocNBEharaHGotohTImmunohistochemical analysis with multiple antibodies in search of prognostic markers for clear cell renal cell carcinomaUrology200769584384817482919

- KramerBAGaoXDavisMHallMHolzbeierleinJTawfikOPrognostic significance of ploidy, MIB-1 proliferation marker, and p53 in renal cell carcinomaJ Am Coll Surg2005201456557016183495

- MahotkaCKriegTKriegADistinct in vivo expression patterns of survivin splice variants in renal cell carcinomasInt J Cancer20021001303612115583

- Di CristofanoCMinerviniAMenicagliMNuclear expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in clear cell renal cell carcinoma is involved in tumor progressionAm J Surg Pathol200731121875188118043042

- PatardJJRioux-LeclercqNMassonDAbsence of VHL gene alteration and high VEGF expression are associated with tumour aggressiveness and poor survival of renal-cell carcinomaBr J Cancer200910181417142419755989

- AaltomaaSLipponenPAla-OpasMEskelinenMSyrjanenKKosmaVMExpression of cyclins A and D and p21(waf1/cip1) proteins in renal cell cancer and their relation to clinicopathological variables and patient survivalBr J Cancer199980122001200710471053

- HaitelAWienerHGNeudertBMarbergerMSusaniMExpression of the cell cycle proteins p21, p27, and pRb in clear cell renal cell carcinoma and their prognostic significanceUrology200158347748111549509

- AbbasTDuttaAp21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activitiesNat Rev Cancer20099640041419440234

- DaiMAl-OdainiAAArakelianARabbaniSAliSLebrunJJA novel function for p21Cip1 and acetyltransferase p/CAF as critical transcriptional regulators of TGFbeta-mediated breast cancer cell migration and invasionBreast Cancer Res2012145R12722995475

- AnanthSKnebelmannBGruningWTransforming growth factor beta1 is a target for the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor and a critical growth factor for clear cell renal carcinomaCancer Res19995992210221610232610

- ShangDLiuYYangPChenYTianYTGFBI-promoted adhesion, migration and invasion of human renal cell carcinoma depends on inactivation of von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressorUrology2012794966.e961e96722341602

- GerlingerMRowanAJHorswellSIntratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencingN Engl J Med20123661088389222397650

- AxelrodDEMillerNChapmanJAAvoiding pitfalls in the statistical analysis of heterogeneous tumorsBiomed Inform Insights20092111820191105