Abstract

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS) is a rare malignant tumor recognized in recent years. It accounts for only 0.4% of soft-tissue sarcomas, and its underlying causes are largely unknown. A correct diagnosis can be difficult to make. Diagnosis of FDCS depends on the combined clinical examination, histopathologic features, electron microscopic examination and confirmation with immunohistochemical studies. Here, we report two rare cases of FDCS: one case involving multiple bones, and the other involving extensive abdominal and pelvic cavities. Clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical aspects, therapeutic options, and a related literature review of the two cases are discussed. As the prevalence of FDCS is increasing, the details of these rare cases may highlight the importance and facilitate treatment of similar diseases.

Introduction

Classified as accessory cells of the immune system, the follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), also known as dendritic reticulum cells, are essential for the humoral response by providing antigen presentation and B-cell response maturation. FDCs are located primarily in the germinal centers of primary and secondary lymphoid follicles of nodal and extranodal sites.Citation1 Lymphoid follicles are found in the lymph nodes and in extranodal lymphoid tissue.Citation2

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS), also known as dendritic reticulum cell sarcoma, is a neoplasm of reticular dendritic origin. Monda et alCitation3 first described this entity in 1986 based on a series of four cases, all of which occurred in lymph nodes. Since then, only a few cases have been reported in the literature. In most of these cases, the major sites affected are the lymph nodes,Citation4–Citation6 and extranodal sites are involved in almost one-third of the patients.Citation7 Because of the low incidence and limited experience of the disease, FDCS is often not considered at the initial evaluation and may be misdiagnosed. Here, we present two rare cases of FDCS: one case involving multiple bones and the other involving extensive abdominal and pelvic cavitities. Upon review of the literature, we identified only two additional cases of FDCS involving bone and four cases involving extensive abdominal and pelvic cavities. Given the rarity of bone or extensive abdominal and pelvic cavity involvement by FDCS and the lack of consensus on treatment, evaluation of this entity must continue.

Case series

Case 1

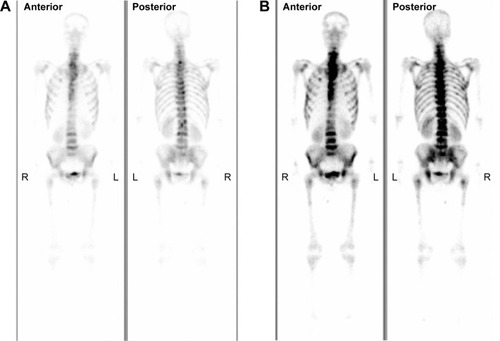

In June 2005, a 24-year-old man presented with intermittent pain in multiple bones such as the thorax, lumbar vertebra, and ribs for 2 months. There was no significant past medical history. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the bilateral axillary and supraclavicular area, and the diameter of the largest one was about 2.1 cm. A subsequent bone scan was acquired and demonstrated high levels of radioactivity accumulation in multiple bones, such as the spine, ribs, shoulder blade, and others (). Abdominal ultrasound scan revealed no abnormalities. Routine biochemical and hematological tests were within normal limits. The patient underwent incision biopsy of the left cervical lymph node. Based on the histopathological and clinical manifestation, the patient was diagnosed with FDCS.

Figure 1 The whole-body bone imaging of case 1.

Abbreviations: L, left; R, right.

Because of the tumor’s unfavorable location and multiple site involvement, surgical therapy was not performed. The patient received four cycles of chemotherapy consisting of etoposide plus cisplatin. To evaluate the efficacy of the therapy, a CT scan was performed, which revealed that the swollen lymph nodes disappeared completely. His symptoms improved immediately. To consolidate and strengthen treatment, an additional six cycles of chemotherapy with a standard dose of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) were performed. This regimen was completed in December 2006. The patient was followed up every 6 months. Up until now, there is no evidence of recurrence.

Case 2

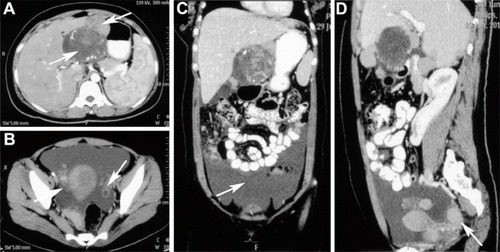

In case 2, a 24-year-old woman had presented with 65 days of delayed menstruation and a 2-month history of lower abdominal fullness, initially. She had a poor appetite and had lost 2 kg in weight. No abdomen ache, diarrhea, or melena was noted. Her physical exam demonstrated a hard, ill-defined, and tender mass in the upper abdominal region and shifting dullness was positive. CT showed lumps of varying sizes in the pelvic and abdominal cavity. Massive ascites and pelvic fluids were found (). No enlarged lymph nodes could be seen in the whole body. Carcinoembryonic antigen and CA19-9 levels were normal. The CA125 level was slightly increased. The patient was diagnosed with ovarian cancer with abdominal and pelvic cavity metastasis initially and received cytoreductive surgery. Macroscopic surgical exploration revealed an encapsulated nodular mass measuring 15×15×10 cm at the lesser curvature of the stomach, and other tumor nodules were dotted around the ovary, anterior wall of the uterus, mesentery, omentum, and liver capsule. Multiple sections were taken from all tumor nodules. An excisional biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and the pathologic findings were consistent with FDCS. Based on the histopathological and immunohistochemical findings, the patient was diagnosed with FDCS of extensive abdominal and pelvic cavity involvement.

Figure 2 Computed tomography images of case 2.

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography.

She received postoperative sequential chemotherapy. Four cycles of CHOP were initiated in July 2012. After three courses of chemotherapy, a subsequent CT scan was performed, which showed the patient’s disease had improved significantly. Two months later, CT revealed the disease had progressed and the regimen was changed to six cycles consisting of ICE (ifosfamid, carboplatin, and etoposide). This regimen was completed in July 2013. When a subsequent positron emission tomographic scan revealed persistent disease, the patient received enterolysis and cytoreductive surgery. After operation, she elected not to receive adjuvant therapy. Unfortunately, her disease could not be controlled and she died 5 months later.

Materials and methods

Pathological materials were taken for routine histologic processing with formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. Sections (4 µm) cut from the tissue blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and used for immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the EnVision method. The panel of antibodies included antibodies against CD21, CD35, CD23, vimentin, CD20, CD30, CD117, S-l00, CD68, CD45, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), D2-40, and Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA (EBER). Antibodies were offered by Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, People’s Republic of China). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed with no modifications. Primary antibodies were replaced by phosphate-buffered saline as a negative control.

Pathologic results

Case 1

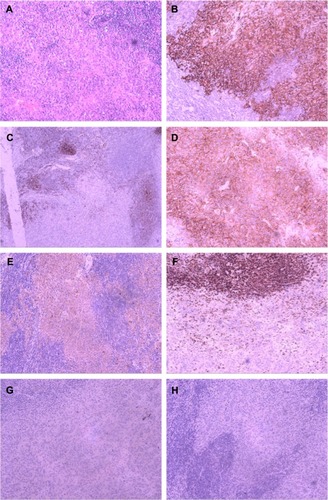

Microscopic examination showed that lymph structure was replaced by the tumor cells arranged in a wispy and storiform pattern. These tumor cells had mild eosinophilic cytoplasm with clear cell borders and the nuclei were small. Small lymphocytes were scattered throughout the tumor cells (). The tumor cells exhibited positive immunohistochemical staining for CD21 and CD35 as well as negative staining for CD23, vimentin, CD20, CD30, CD117, EMA, S-l00, CD45, CD68, D2-40, and EBER ().

Figure 3 Tumor histology of case 1.

Abbreviation: EBER, Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA.

Case 2

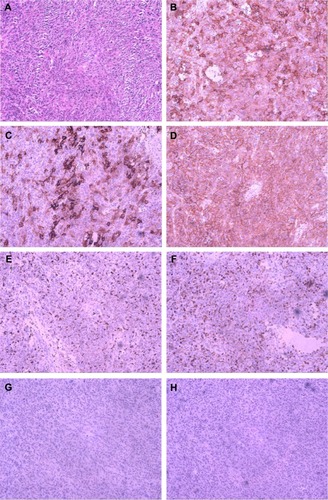

Microscopic examination revealed that the lesser curvature of the stomach tumor was composed of oval and long spindle cells that were arranged in bundles. These tumor cells had mild eosinophilic cytoplasm with distinct cell borders and chromatin that were in the shape of physalides (). Immunoperoxidase staining showed tumor cells to be reactive with CD21, CD35, CD23, vimentin, CD30, and EMA. There was no reactivity with antibodies to CD20, CD68, S-100, CD117, D2-40, CD45, or EBER (). Tumor cells of the same origin were found at the ovary, uterus, and other sites.

Figure 4 Tumor histology of case 2.

Abbreviation: EBER, Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA.

Discussion

FDCS usually occurs in lymph nodes, especially in the cervical, mediastinal, and axillary areas, but it can occur in extranodal sites such as in the liver, lungs, tonsils, or spleen.Citation8 It is a rare tumor that presents in a wide range of ages. FDCS generally affects young to middle-aged adults, without sex predilection.Citation4 Both cases in our report were only 24 years old. The causes of FDCS are largely unknown. Associations with Castleman diseaseCitation9 have been reported. The Epstein–Barr virus is suspected to carry a viral oncogene that might encourage transformation.Citation10

Pathological diagnosis is essential for FDCS. FDCS may be suspected if the tumor exhibits distinct microscopic features, such as a storiform arrangement of spindle-shaped cells and a background of lymphocytes scattered throughout the neoplastic cells.Citation11 The morphologies of our cases are typical of FDCS. To confirm the tumor, immunohistochemical staining is also required. The most widely used FDC markers, including CD21, CD35, and CD23, can be used for confirmation. Other markers including vimentin, CD68, CD45, CD3, CD20, EMA, melanoma (HMB-45), and Ki-67 (MIB-1) can be variably positive, although they lack specificity. The S-100 and certain vascular or muscular markers may also help to distinguish this tumor from other tumors, such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.Citation12 The diagnosis of an FDC tumor is established based on the findings of morphology and immunohistochemistry. Ultrastructural studies may be helpful but are not indispensable for accurate diagnosis. The most distinctive feature is numerous long, slender, interwoven cytoplasmic processes joined by well-formed desmosomes.Citation13

The optimal treatment for FDCS is yet to be found, owing to limited experience. A complete surgical excision is the appropriate initial therapy.Citation2 The role of adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy or chemotherapy) remains unclear because of the rarity of the disease. Adjuvant therapy appears to be indicated in cases of incompletely resected lesions or adverse pathological features during recurrence.Citation14 Because curative surgery was not possible for the patient with multiple bone metastases, we opted for chemotherapy for case 1. As for the second patient, we chose chemotherapy combined with cytoreductive surgery. Both patients were given CHOP regimen. This regimen was widely used and showed its efficacy in our study. Other chemotherapeutic agents such as ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine), EPOCH (etoposide, prednisolone, oncovin, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin), ICE, and cisplatin/epirubicin have also been proposed with inconsistent results.Citation15 Imatinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatinCitation16 and rituximabCitation17 was also reported to have some activity against FDCS.

FDCS is considered as an intermediate-grade malignancy. Chan et alCitation4 analyzed the clinicopathologic features of 17 cases of FDCS and found that the overall recurrence, metastasis, and mortality rates were 43%, 24%, and 17%, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, only two well-documented cases of FDCS of bone involvement have been reported in the English literature (). In one patient, originating in the mediastinum, the tumor metastasized to the pelvic bone and involved the bone marrow after 18 months. The patient received chemotherapy and lived with the tumor in the follow-up 2 years. The other patient with multiple bone metastases received 12 cycles of chemotherapy. In a follow-up 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient’s disease was rated as stable. There was no significant correlation of the clinical outcome with histological features. Our patient (Case 1) presented with bone metastasis, and his disease was stable in the follow-up 9 years after appropriate therapy. Although there are a limited number of cases, we can conclude that FDCS involving bone shows slow progress after correct chemotherapy.

Table 1 Summary of three cases of FDCS involving bone

Extensive abdominal or pelvic involvement by FDCS was unusual. We identified five similar reports in the literature and the present case adds to this total (). The age of patients at diagnosis ranged from 24 to 70 years (mean, 43.8 years). The common feature of these cases is that the multiple organ metastasis occurred at first and pursued an aggressive and rapid course. Some studies show that those with unfavorable prognostic factors, such as coagulative necrosis, high mitotic count (≥5 per 10 high-power fields), significant cellular atypia or a tumor diameter of greater than 6 cm, or intra-abdominal involvement, pursued a rapidly fatal clinical course.Citation4,Citation24 In case 2, we also demonstrated a trend toward higher recurrence and worse prognosis. Thus, intra-abdominal or pelvic cavity FDCS may have a higher degree of malignancy than we recognize and should be worthy of more attention.

Table 2 Summary of five cases of FDCS involving extensive abdominal and pelvic cavities

Conclusion

FDCS is a rare entity and has been recognized with increasing frequency. The diagnosis must be kept in mind when confronted with uncommon histological features in lymphoid tissue. Complete surgical excision is currently the best method to treat early-stage FDCS. Even though no consensus on adjuvant therapy has been developed, chemotherapy may be a good option in patients with advanced unresectable disease and could extend the survival of a patient with FDCS to a certain extent. Pathogenesis and therapy of FDCS needs further investigation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- van NieropKde GrootCHuman follicular dendritic cells: function, origin and developmentSemin Immunol200214425125712163300

- KarabulutBOrhanKSGuldikenYFollicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the nasopharynxInt J Oral Maxillofac Surg201241221822021835593

- MondaLWarnkeRRosaiJA primary lymph node malignancy with features suggestive of dendritic reticulum cell differentiation. A report of 4 casesAm J Pathol198612235622420185

- ChanJKFletcherCDNaylerSJFollicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 17 cases suggesting a malignant potential higher than currently recognizedCancer19977922943139010103

- GroggKLLaeMEKurtinPJClusterin expression distinguishes follicular dendritic cell tumors from other dendritic cell neoplasms: report of a novel follicular dendritic cell marker and clinicopathologic data on 12 additional follicular dendritic cell tumors and 6 additional interdigitating dendritic cell tumorsAm J Surg Pathol200428898899815252304

- CheukWChanJKCShekTWHInflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor: a distinctive low-grade malignant intra-abdominal neoplasm with consistent Epstein–Barr virus associationAm J Surg Pathol200125672173111395549

- YouensKEWaughMSExtranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcomaArch Pathol Lab Med2008132101683168718834231

- SayginCUzunaslanDOzgurogluMDendritic cell sarcoma: a pooled analysis including 462 cases with presentation of our case seriesCrit Rev Oncol Hematol201388225327123755890

- ShinagareABRamaiyaNHJagannathanJPPrimary follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of liver treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone regimen and surgeryJ Clin Oncol20112935e849e85122042944

- ArberDAWeissLMChangKLDetection of Epstein-Barr Virus in inflammatory pseudotumorSemin Diagn Pathol19981521551609606806

- ShiaJChenWTangLHExtranodal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: clinical, pathologic, and histogenetic characteristics of an under-recognized disease entityVirchows Arch2006449214815816758173

- Long-HuaQQinXYa-JiaGImaging findings of follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: report of four casesKorean J Radiol201112112212821228948

- WangHSuZHuZFollicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a report of six cases and a review of the Chinese literatureDiagn Pathol2010511620205795

- MondalSKBeraHBhattacharyaBFollicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the tonsilNatl J Maxillofac Surg2012316223251062

- KairouzSHashashJKabbaraWDendritic cell neoplasms: an overviewAm J Hematol2007821092492817636477

- AzimHAElsedewyEAzim JrHAImatinib in the treatment of follicular dendritic sarcoma: a case report and review of literatureOncol Res Treat2007307381384

- MeijsMMekkesJVan NoeselCParaneoplastic pemphigus associated with follicular dendritic cell sarcoma without Castleman’s disease; treatment with rituximabInt J Dermatol200847663263418477166

- JiangLAdmirandJHMoranCMediastinal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma involving bone marrow: a case report and review of the literatureAnn Diagn Pathol200610635736217126255

- JiangLTanHWangWA rare case of follicular dendritic cell sarcoma involving multiple bonesClin Nucl Med201338758258523640234

- JingLRuiZZhenglongZA rare case of recurrent follicular dendritic cell sarcomaChin J Pathot20103910709710

- DongAWangYZuoCFDG PET/CT in follicular dendritic cell sarcoma with extensive peritoneal involvementClin Nucl Med201439653453624476636

- LiCFChuangSSLinCNA 70-year-old man with multiple intra-abdominal masses and liver and spleen metastases. Intra-abdominal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma with liver and spleen metastasesArch Pathol Lab Med20051295e13015859660

- LiberaleGKeriakosKAzeradMAIntraperitoneal follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: role of chemotherapy and bone marrow allotransplantation in locally advanced disease?Clin Med Insights Oncol2015991325698886

- Perez-OrdonezBErlandsonRARosaiJFollicular dendritic cell tumor: report of 13 additional cases of a distinctive entityAm J Surg Pathol19962089449558712294